Spectrophotometric Polyvinyl Alcohol Detection and Validation in Wastewater Streams: From Lab to Process Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PVA Analytics

2.1.1. Equipment and Chemicals

2.1.2. Preparation of Standard Solution

2.1.3. Standard Protocol for Polyvinyl Alcohol Quantification in Water

2.1.4. Determination of Optimal Measurement Wavelength (λmax)

2.1.5. Quality Assurance Measures

2.2. Lab-Scale Optimization of PVA Removal with an AOP (UV/H2O2)

2.3. Removal of PVA and Microplastics via Pilot-Scale GAC and Organosilane-Induced Agglomeration

2.4. WSSP or PVA Removal Efficiency

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Validation of the Detection Method

3.1.1. Calibration Curve, Detection Limits, and Recovery Rates

3.1.2. Comparison of PVAs with Different Molecular Weights and Hydrolyzation

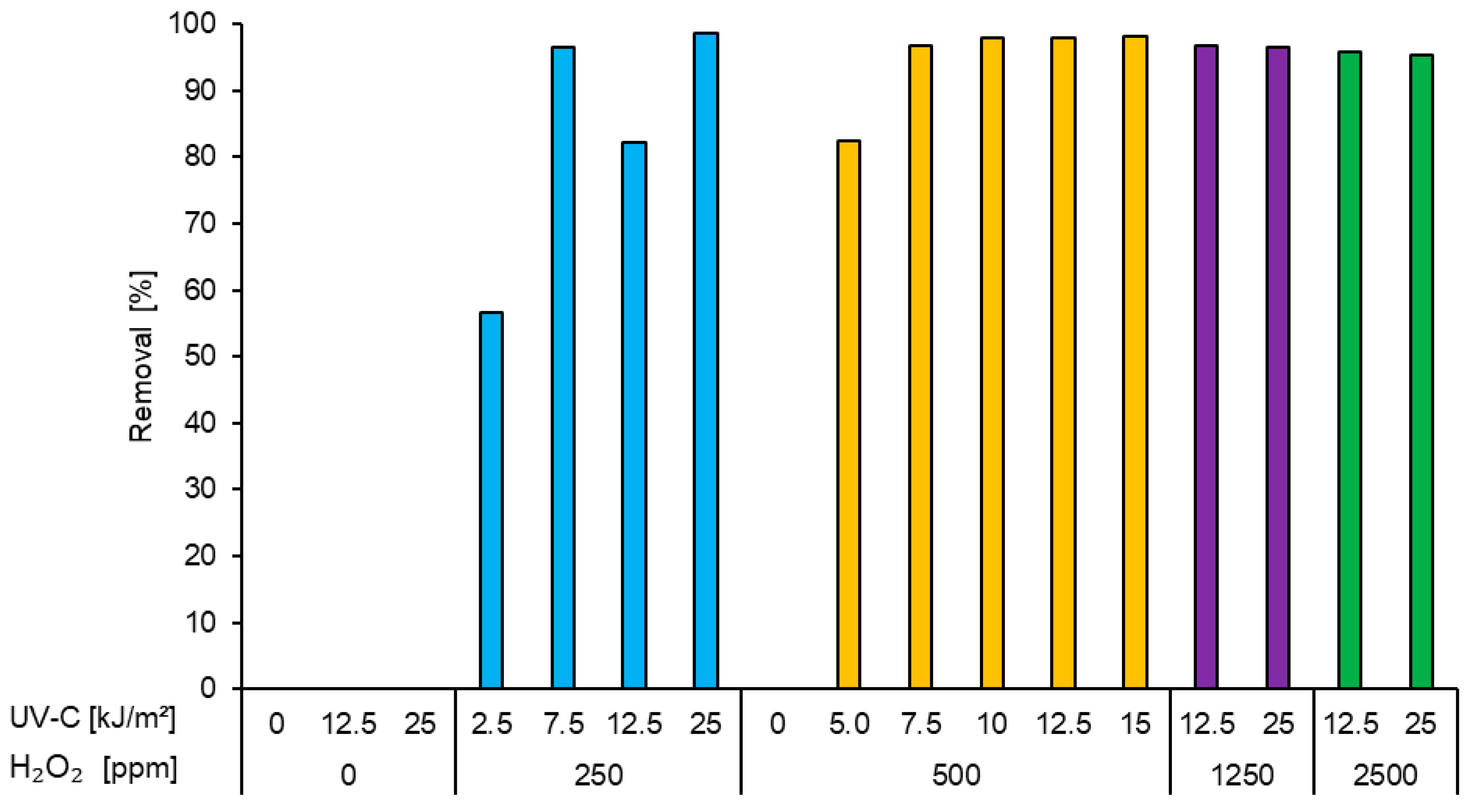

3.2. PVA Removal with AOP at Laboratory-Scale

3.2.1. Removal Trial with 250 mg/L PVA

3.2.2. Removal Trials with 2500 mg/L PVA

3.2.3. Removal Trial 4000 and 5000 mg/L PVA

3.3. Removal of PVA and Microplastics at Pilot-Scale

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOP | Advanced oxidation process |

| DH | Degree of hydrolyzation |

| GAC | Granular activated carbon |

| MP | Microplastics |

| MW | Molecular weight |

| PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| UV-C | UV-C light |

| WSSP | Water soluble synthetic polymer |

References

- Alonso-López, O.; López-Ibáñez, S.; Beiras, R. Assessment of Toxicity and Biodegradability of Poly(vinyl alcohol)-Based Materials in Marine Water. Polymers 2021, 13, 3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigro, L.; Magni, S.; Ortenzi, M.A.; Gazzotti, S.; Della Torre, C.; Binelli, A. Are “liquid plastics” a new environmental threat? The case of polyvinyl alcohol. Aquat. Toxicol. 2022, 248, 106200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, Z.; Dhib, R.; Mehrvar, M. Continuous UV/H2O2 Process: A Sustainable Wastewater Treatment Approach for Enhancing the Biodegradability of Aqueous PVA. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, M.; Minge, O. Biodegradability of Poly(vinyl acetate) and Related Polymers. In Synthetic Biodegradable Polymers; Rieger, B., Künkel, A., Coates, G.W., Reichardt, R., Dinjus, E., Zevaco, T.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 137–172. ISBN 978-3-642-27153-3. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Chen, L.; Wang, J. Degradation of PVA (polyvinyl alcohol) in wastewater by advanced oxidation processes. J. Adv. Oxid. Technol. 2017, 20, 20170018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, R.J.; Robertson, A.; Mallon, P.E.; Thompson, R.L. The Impact of Plasticizer and Degree of Hydrolysis on Free Volume of Poly(vinyl alcohol) Films. Polymers 2018, 10, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolsky, C.; Kelkar, V. Degradation of Polyvinyl Alcohol in US Wastewater Treatment Plants and Subsequent Nationwide Emission Estimate. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiellini, E.; Corti, A.; D’Antone, S.; Solaro, R. Biodegradation of poly (vinyl alcohol) based materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2003, 28, 963–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMerlis, C.C.; Schoneker, D.R. Review of the oral toxicity of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). Food Chem. Toxicol. 2003, 41, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeshan, M.H.; Ruman, U.E.; He, G.; Sabir, A.; Shafiq, M.; Zubair, M. Environmental Issues Concerned with Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) (PVA) in Textile Wastewater. In Polymer Technology in Dye-containing Wastewater; Khadir, A., Muthu, S.S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 225–236. ISBN 978-981-19-1515-4. [Google Scholar]

- Khadir, A.; Muthu, S.S. (Eds.) Polymer Technology in Dye-containing Wastewater; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; ISBN 978-981-19-1515-4. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, K.; Hall, M.J.; Wilcox, A.; Menzies, J.; Brill, J.; Morris, B.; Connors, K. Application of standardized methods to evaluate the environmental safety of polyvinyl alcohol disposed of down the drain. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2024, 20, 1693–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, D.; Dhib, R.; Mehrvar, M. Photochemical Degradation of Aqueous Polyvinyl Alcohol in a Continuous UV/H2O2 Process: Experimental and Statistical Analysis. J. Polym. Environ. 2016, 24, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, D.; Mehrvar, M.; Dhib, R. Experimental study of polyvinyl alcohol degradation in aqueous solution by UV/H2O2 process. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2014, 103, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-C.; Lee, L.-T. Degradation of polyvinyl alcohol in aqueous solutions using UV/oxidant process. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 21, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Kim, S.; Choi, K.; Kim, J.-O. Degradation of polyvinyl alcohol in textile waste water by Microbacterium barkeri KCCM 10507 and Paenibacillus amylolyticus KCCM 10508. Environ. Technol. 2016, 37, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Hu, X.; Yue, P.L.; Bossmann, S.H.; Göb, S.; Braun, A.M. Oxidative degradation of poly vinyl alcohol by the photochemically enhanced Fenton reaction. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 1998, 116, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulthess, C.P.; Tokunaga, S. Adsorption Isotherms of Poly(vinyl alcohol) on Silicon Oxide. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1996, 60, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, A.K.; Vishwakarma, N. Adsorption of polyvinylalcohol onto Fuller’s earth surfaces. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2003, 220, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, T. Adsorption of polyvinyl alcohol on silica at various ph values and its effect on the flocculation of the dispersion. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1978, 64, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházková, L.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, Y.; Procházka, J.; Wanner, J. Simple spectrophotometric method for determination of polyvinylalcohol in different types of wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2014, 94, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasser 3.0 gGmbH. Instructions for the Quantitative Analysis of Wastewater for Water Soluble Polymers (WSSP). Available online: https://wasserdreinull.de/wp-content/uploads/W30_Manual-WSSP-Detektion-Quantitativ-EN-v3.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Wasser 3.0 gGmbH. Instructions for the Qualitative Analysis of Wastewater for Water Soluble Polymers (WSSP). Available online: https://wasserdreinull.de/wp-content/uploads/W30_Manual-WSSP-Detektion-Qualitativ-EN-v4.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Chen, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Guo, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, N. Research on the Thermal Aging Mechanism of Polyvinyl Alcohol Hydrogel. Polymers 2024, 16, 2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsioptsias, C.; Fardis, D.; Ntampou, X.; Tsivintzelis, I.; Panayiotou, C. Thermal Behavior of Poly(vinyl alcohol) in the Form of Physically Crosslinked Film. Polymers 2023, 15, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, T. Fundamentals of UV-Visible Spectroscopy: A Primer; Hewlett-Packard: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sturm, M.T.; Myers, E.; Korzin, A.; Polierer, S.; Schober, D.; Schuhen, K. Fast Forward: Optimized Sample Preparation and Fluorescent Staining for Microplastic Detection. Microplastics 2023, 2, 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.G.; Akintola, D.A. Complexation of polyvinyl alcohol with iodine Analytical precision and mechanism. Talanta 1972, 19, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macias, C.E.; Bodugoz-Senturk, H.; Muratoglu, O.K. Quantification of PVA hydrogel dissolution in water and bovine serum. Polymer 2013, 54, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, D.P.; Lan-Chun-Fung, Y.L.; Pritchard, J.G. Determination of poly(vinyl alcohol) via its complex with boric acid and iodine. Anal. Chim. Acta 1979, 104, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishima, Y.; Fujisawa, K.; Nozakura, S. Sequence Length Required for Poly(vinyl acetate)—Iodine and Poly(vinyl alcohol)—Iodine Color Reactions. Polym. J. 1978, 10, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwick, M.M. Poly(vinyl alcohol)–iodine complexes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1965, 9, 2393–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, Z.; Dhib, R.; Mehrvar, M. pH and UVA real-time data feasibility for monitoring aqueous PVA degradation in a continuous pilot-scale UV/H2O2 photoreactor: Experimental and statistical analysis. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 103, 6056–6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wols, B.A.; Harmsen, D.; van Remmen, T.; Beerendonk, E.F.; Hofman-Caris, C. Design aspects of UV/H2O2 reactors. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 137, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.-Y.; Kim, H.-W.; Park, J.-M.; Park, H.-S.; Yoon, C. Oxidation of polyvinyl alcohol by persulfate activated with heat, Fe2+, and zero-valent iron. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 168, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, G.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, P.; Ge, M. The experimental study of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) textile material degradation by ozone oxidation process. J. Text. Inst. 2021, 112, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, M.T.; Herbort, A.F.; Horn, H.; Schuhen, K. Comparative study of the influence of linear and branched alkyltrichlorosilanes on the removal efficiency of polyethylene and polypropylene-based microplastic particles from water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2020, 27, 10888–10898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, T.; Vincent, B. The influence of electrolytes on the adsorption of poly(vinyl alcohol) on polystyrene particles and on the stability of the polymer-coated particles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1979, 72, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.K.; Kim, J.-H.; Guo, X.; Park, H.-S. Adsorption equilibrium and kinetics of polyvinyl alcohol from aqueous solution on powdered activated carbon. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 153, 1207–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamagata, T.; Banno, S. Process for Separating Polyvinyl Alcohol from Its Solution. US4078129, 14 March 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata, T.; Banno, S. Process for Treating Waste Water Containing Polyvinyl Alcohol. EP054752 A1, 30 June 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Hadrup, N.; Frederiksen, M.; Sharma, A.K. Toxicity of boric acid, borax and other boron containing compounds: A review. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 121, 104873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, M.S.; Lipnizki, F.; Abdallah, H.; Shaban, A.M.; Ramadan, R.; Mansor, E.; Hosney, M.; Thomas, A.; Babu, B.M.; Rose, K.E.M.; et al. Removal of PVA from textile wastewater using modified PVDF membranes by electrospun cellulose nanofibers. Appl. Water Sci. 2025, 15, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| c PVA Standard [mg/L] | c PVA Measured [mg/L] | Recovery Rate [%] |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 ± 0.1 | n.d. |

| 10 | 10.8 ± 1 | 108.2 ± 9.9 |

| 20 | 20.1 ± 0.5 | 100.3 ± 2.3 |

| 35 | 35.1 ± 0.9 | 100.2 ± 2.4 |

| 50 | 49.3 ± 1.2 | 98.6 ± 2.5 |

| 100 | 98.2 ± 3.1 | 98.2 ± 3.1 |

| 200 | 200.7 ± 7.4 | 100.3 ± 3.7 |

| 300 | 299.9 ± 12.3 | 100 ± 4.1 |

| 400 | 398.8 ± 11.7 | 99.7 ± 2.9 |

| 500 | 501.1 ± 15.8 | 100.2 ± 3.2 |

| Average | 100.6 ± 2.8 |

| Hydrolyzation [%] | Mw [mol/g] | λmax | A (λmax) | A (580 nm) | Calc. Concentration (mg/L) | Recovery [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 400–600 | 657 | 1.59 | 1.17 | 244 | 122 |

| 99+ | 85,000–124,000 | 645 | 1.25 | 0.98 | 205 | 103 |

| 99+ | 146,000–186,000 | 644 | 1.17 | 0.92 | 193 | 96 |

| 99.0–99.8 | 145,000 | 638 | 1.08 | 0.89 | 185 | 92 |

| 98.0–98.8 | 27,000 | 665 | 1.82 | 1.28 | 267 | 134 |

| 98.0–98.8 | 125,000 | 646 | 1.25 | 0.97 | 203 | 101 |

| 98.0–98.8 | 195,000 | 639 | 1.15 | 0.93 | 193 | 97 |

| 87–90 | 30,000–70,000 | 658 | 1.69 | 1.26 | 263 | 131 |

| 86.7–88.7 | 67,000 | 656 | 1.61 | 1.20 | 251 | 125 |

| 86.7–88.7 | 130,000 | 653 | 1.37 | 1.02 | 213 | 107 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sturm, M.T.; Korzin, A.; Ronsse, P.; Kormelinck, K.G.; Myers, E.; Zernikel, O.; Schober, D.; Schuhen, K. Spectrophotometric Polyvinyl Alcohol Detection and Validation in Wastewater Streams: From Lab to Process Control. Water 2025, 17, 3465. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243465

Sturm MT, Korzin A, Ronsse P, Kormelinck KG, Myers E, Zernikel O, Schober D, Schuhen K. Spectrophotometric Polyvinyl Alcohol Detection and Validation in Wastewater Streams: From Lab to Process Control. Water. 2025; 17(24):3465. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243465

Chicago/Turabian StyleSturm, Michael Toni, Anika Korzin, Pieter Ronsse, Kaspar Groot Kormelinck, Erika Myers, Oleg Zernikel, Dennis Schober, and Katrin Schuhen. 2025. "Spectrophotometric Polyvinyl Alcohol Detection and Validation in Wastewater Streams: From Lab to Process Control" Water 17, no. 24: 3465. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243465

APA StyleSturm, M. T., Korzin, A., Ronsse, P., Kormelinck, K. G., Myers, E., Zernikel, O., Schober, D., & Schuhen, K. (2025). Spectrophotometric Polyvinyl Alcohol Detection and Validation in Wastewater Streams: From Lab to Process Control. Water, 17(24), 3465. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243465