Has the Water Rights Trading Policy Improved Water Resource Utilization Efficiency?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Institutional Background

2.2. Measuring Water Resource Efficiency

2.3. Theory and Hypothesis

2.3.1. Direct Impact of WET on WEE

2.3.2. Heterogeneity of WET Impacts on WEE

2.3.3. Mechanisms Through Which WET Affects WEE

3. Method

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

3.2. Measurement Model Setting and Variable Measurement

3.2.1. Measurement Model

3.2.2. Variable Measurement

4. Empirical Research

4.1. Benchmark Regression Results

4.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.2.1. Analysis of Urban Geographical Heterogeneity

4.2.2. Analysis of Water Resource Heterogeneity

4.2.3. Analysis of Industrial Development Heterogeneity

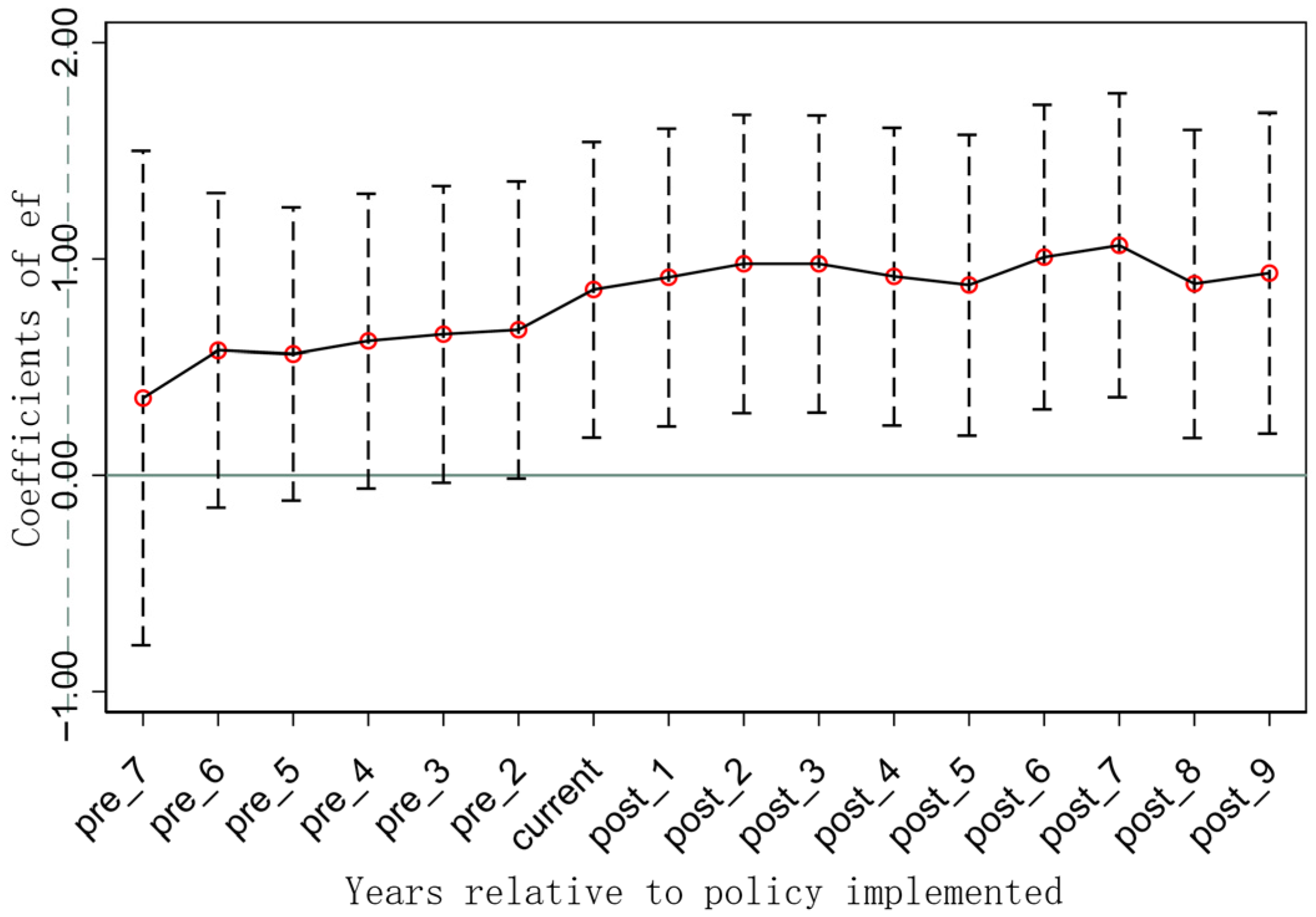

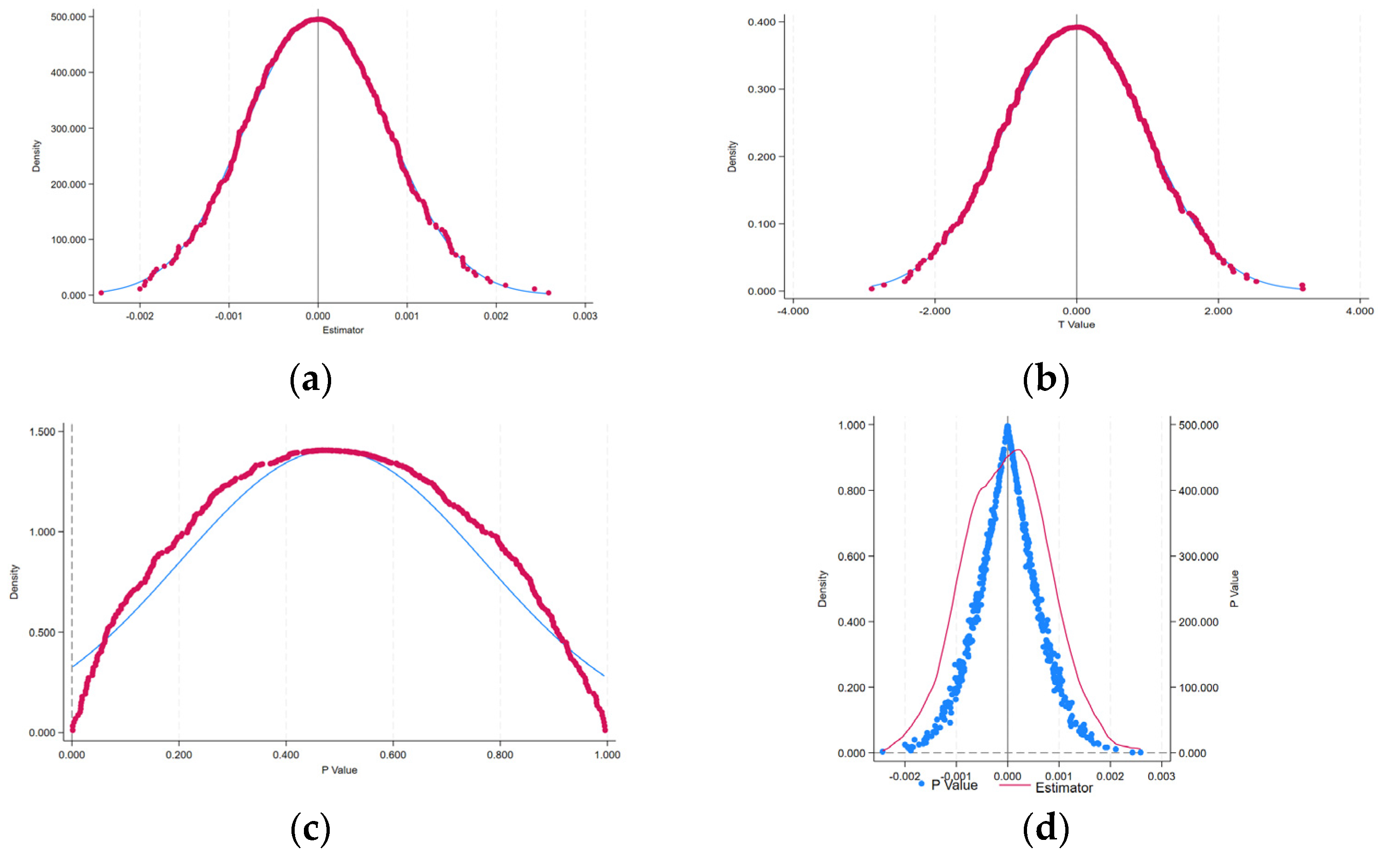

4.3. Placebo Test

4.4. Robustness Test

4.4.1. Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

4.4.2. Entropy Matching

4.4.3. Dual Machine Learning Model

4.5. Mechanism Analysis

4.5.1. Market Vitality

4.5.2. Water Conservation Benefits

4.5.3. Technological Innovation Output

4.6. Spatial Effects Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Auci, S.; Pronti, A. Irrigation Technology Adaptation for a Sustainable Agriculture: A Panel Endogenous Switching Analysis on the Italian Farmland Productivity. Resour. Energy Econ. 2023, 74, 101391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yang, R. Does Agricultural Water Conservation Policy Necessarily Reduce Agricultural Water Extraction? Evidence from China. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 274, 107987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C. Trade-off between the Future Water Resource Utilization and Grain Production in a Water-Deficient Region from the Perspective of the Water–Land–Grain Nexus. J. Hydrol. 2024, 640, 131697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Oki, T. Water Pricing Reform for Sustainable Water Resources Management in China’s Agricultural Sector. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 275, 108045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Peng, J.; Yang, X.; Xuan, S. Does Water Rights Trading Promote Resources Utilisation Efficiency and Green Growth? Evidence from China’s Resources Trading Policy. Resour. Policy 2023, 86, 104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Yu, J.; Du, C.; Wang, P. A Policy Support Framework for the Balanced Development of Economy-Society-Water in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Urban Agglomeration. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 374, 134009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Che, L.; Wang, Z. Where Are the Critical Points of Water Transfer Impact on Grain Production from the Middle Route of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project? J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 436, 140465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, W.U.H.; Hao, G.; Yasmeen, R.; Yan, H.; Shen, J.; Lu, Y. Role of China’s Agricultural Water Policy Reforms and Production Technology Heterogeneity on Agriculture Water Usage Efficiency and Total Factor Productivity Change. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 287, 108429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, H.; He, H.; Wu, Y.; Delang, C.O.; Wu, J.; Lu, J.; Yao, Z.; Hu, Y.; Gomez, C. Quantifying the Heterogeneity of Urban Water Resources Utilization Efficiency through Meta-Frontier Super SBM Model: Application in the Yellow River Basin. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 485, 144410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, S. Breaking the Dilemma of Agricultural Water Fee Collection in China. Water Policy 2014, 16, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.; Zhang, R.; Yang, H.; Chen, C. Water Markets and Water Rebounds: China’s Water Rights Trading Policy. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 229, 108471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, L.; Wang, C.; Xue, B.; Wang, H.; Li, S. Assessing the Impact of Water Price Reform on Farmers’ Willingness to Pay for Agricultural Water in Northwest China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 1072–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kejser, A. European Attitudes to Water Pricing: Internalizing Environmental and Resource Costs. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 183, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Wu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Li, J.; Zhu, M. The Impact of Integrated Agricultural Water Pricing Reform on Farmers’ Income in China. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 299, 108902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yin, G.; Liu, K. Regional Differences in the Industrial Water Use Efficiency of China: The Spatial Spillover Effect and Relevant Factors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 167, 105239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, H. Will Alleviating Energy Poverty Enhance Social Trust in China? An Approach Based on Dual Machine Learning Modeling. Energy Econ. 2025, 147, 108560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Shi, H.; Yuan, S.; Chen, K.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J. How Does Farmer Differentiation Effect Agricultural Water Use Efficiency? Evidence from China. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 312, 109436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Lei, Y.; Yao, H.; Ge, J.; Wu, S.; Liu, L. Estimation and Influencing Factors of Agricultural Water Efficiency in the Yellow River Basin, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 308, 127249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Kumar, S.; Huang, Z.; Liu, R. Water Resource Management and Policy Evaluation in Middle Eastern Countries: Achieving Sustainable Development Goal 6. Desalin. Water Treat. 2024, 320, 100829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebil, A.; Soula, R.; Souissi, A.; Bennouna, B. Efficiency, Valuation, and Pricing of Irrigation Water in Northeastern Tunisia. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 266, 107577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Zhao, N.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X. The Impact of Water Rights Trading on Water Resource Use Efficiency: Evidence from China’s Water Rights Trading Pilots. Water Resour. Econ. 2024, 46, 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Broek, J.; Førsund, F.R.; Hjalmarsson, L.; Meeusen, W. On the Estimation of Deterministic and Stochastic Frontier Production Functions: A Comparison. J. Econom. 1980, 13, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigner, D.; Lovell, C.A.K.; Schmidt, P. Formulation and Estimation of Stochastic Frontier Production Function Models. J. Econom. 1977, 6, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Zhang, L. Does the Trading of Water Rights Encourage Technology Improvement and Agricultural Water Conservation? Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 233, 106097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Z. Resource regulation and green innovation: Evidence from China’s water rights trading policy. Environ. Res. 2024, 258, 119443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koop, S.H.A.; Van Dorssen, A.J.; Brouwer, S. Enhancing Domestic Water Conservation Behaviour: A Review of Empirical Studies on Influencing Tactics. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 247, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Guo, M.; Zhao, X.; Shu, X. Spatio-Temporal Characteristics and Coupling Coordination Factors of Industrial Water Resource System Resilience and Utilization Efficiency: A Case Study of the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, S. Measurement and Evaluation of Agricultural Technological Innovation Efficiency in the Yellow River Basin of China under Water Resource Constraints. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Huang, C.; Chen, Z. Evaluating the Water-Saving and Wastewater-Reducing Effects of Water Rights Trading Pilots: Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 319, 115706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, W.U.H.; Hao, G.; Yasmeen, R.; Yan, H.; Qi, Y. Impact of Agricultural Technological Innovation on Total-Factor Agricultural Water Usage Efficiency: Evidence from 31 Chinese Provinces. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 299, 108905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Arteaga, F.J.; Buendía, A.; André, F.J. A dynamic approach to analyze the evolution of water use efficiency across Spanish regions. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 389, 126174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Yang, R. The Impact of Water Rights Reform on Economic Development: Evidence from City-Level Panel Data in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 374, 124082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Li, Z.; Fang, J.; He, Z.; Zhang, X. Can the Water Resources Tax Promote the Water-Saving Innovation Performance of High Water Consumption Companies? -Empirical Analysis from the Pilot Provinces in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 451, 141888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shi, K.; Wang, Z.; Jin, C. Policy Effects of Water Rights Trading (WRT). Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 24, 100537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S. Alleviating Water Scarcity and Poverty through Water Rights Trading Pilot Policy: A Quasi-Natural Experiment Based Approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 823, 153318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, S.A.; Carmody, E.; Grafton, R.Q.; Kingsford, R.T.; Zuo, A. The rebound effect on water extraction from subsidising irrigation infrastructure in Australia. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 159, 104755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanemann, M. Property rights and sustainable irrigation—A developed world perspective. Agric. Water Manag. 2014, 145, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoccaro, G.; Roselli, L.; Sardaro, R.; de Gennaro, B.C. Design of an Incentive-Based Tool for Effective Water Saving Policy in Agriculture. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 272, 107866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Li, Y.P.; Huang, G.H.; Zhai, X.B.; Ma, Y. Improving Efficiency and Sustainability of Water-Agriculture-Energy Nexus in a Transboundary River Basin under Climate Change: A Double-Sided Stochastic Factional Optimization Method. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 292, 108648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Sample Size | Mean | Sd | Min | Max | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WEE | 4698 | 95.707 | 7.870 | 62.688 | 100.00 | |

| WRT | 4698 | 0.170 | 0.376 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.050 |

| Lab | 4698 | 0.572 | 0.153 | 0.22 | 1.020 | 1.380 |

| Ind | 4698 | 41.160 | 9.797 | 20.70 | 70.020 | 1.930 |

| Eco | 4698 | 10.550 | 0.715 | 8.80 | 12.020 | 3.750 |

| City | 4681 | 0.532 | 0.163 | 0.20 | 0.941 | 2.990 |

| Tec | 4698 | 10.094 | 1.654 | 6.26 | 14.440 | 2.510 |

| Variables | (2) | (1) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model (2) | Model (1) | Model (3) | Model (4) | |

| WEE | WEE | WEE | WEE | |

| WET | 9.2099 *** | 0.2736 ** | 0.0894 *** | 0.5111 *** |

| (0.3772) | (0.1367) | (0.0331) | (0.1423) | |

| Tec | 0.1224 *** | −0.3028 *** | ||

| (0.0309) | (0.0843) | |||

| Eco | 1.4416 *** | 0.9603 *** | ||

| (0.1499) | (0.2740) | |||

| Indu | −0.0502 *** | −0.0736 *** | ||

| (0.0052) | (0.0108) | |||

| Urba | −2.1592 *** | −0.9063 | ||

| (0.5276) | (1.0899) | |||

| Labor | 3.4214 *** | 3.9104 *** | ||

| (0.3183) | (0.4933) | |||

| Constant | 94.1403 *** | 95.6601 *** | 80.5212 *** | 89.8391 *** |

| (0.1530) | (0.0374) | (1.3702) | (2.8213) | |

| Observations | 4698 | 4698 | 4676 | 4675 |

| City | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| Year | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| R-squared | 0.124 | 0.933 | 0.931 | 0.939 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yangtze River Economic Belt | Non-Yangtze River Economic Belt | North | South | |

| WET | 1.6136 *** | −0.0831 | 0.0997 | 0.7042 *** |

| (0.2525) | (0.1829) | (0.2330) | (0.1899) | |

| Tec | −0.5311 *** | −0.2684 ** | −0.3978 *** | −0.1559 |

| (0.1516) | (0.1053) | (0.1320) | (0.1114) | |

| Eco | 0.4282 | 1.0638 *** | 1.9251 *** | 0.3217 |

| (0.5178) | (0.3492) | (0.4387) | (0.4131) | |

| Indu | −0.0914 *** | −0.0603 *** | −0.0932 *** | −0.0384 *** |

| (0.0197) | (0.0137) | (0.0167) | (0.0138) | |

| Urban | 3.2110 | −3.7907 *** | −7.2123 *** | 6.4884 *** |

| (1.9605) | (1.3524) | (1.5540) | (1.5456) | |

| Labor | 2.5248 *** | 5.1060 *** | 4.5127 *** | 3.6676 *** |

| (0.6385) | (0.7380) | (0.7850) | (0.5878) | |

| Constant | 97.2719 *** | 88.7077 *** | 84.1795 *** | 89.9688 *** |

| (5.8283) | (3.5078) | (4.2923) | (4.4256) | |

| Observations | 1878 | 2797 | 1997 | 2678 |

| R-squared | 0.947 | 0.935 | 0.935 | 0.946 |

| between-group differences | −1.697 *** | 0.352 *** | ||

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Wet Areas | Non-Wet Area | |

| WET | 0.8809 *** | 0.2346 |

| (0.2043) | (0.2098) | |

| Tec | −0.1325 | −0.3061 ** |

| (0.1140) | (0.1212) | |

| Eco | 0.6842 | 1.1356 *** |

| (0.4365) | (0.3717) | |

| Indu | −0.0237 * | −0.1095 *** |

| (0.0141) | (0.0161) | |

| Urban | 6.9303 *** | −5.8574 *** |

| (1.6161) | (1.4638) | |

| Labor | 5.0289 *** | 3.2036 *** |

| (0.7207) | (0.6750) | |

| Constant | 84.3182 *** | 92.1552 *** |

| (4.6609) | (3.6847) | |

| Observations | 2271 | 2364 |

| R-squared | 0.950 | 0.938 |

| between-group differences | −0.646 ** | |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Old Industrial Base | Non-Old Industrial Base | |

| WET | 0.6498 *** | 0.3250 |

| (0.1753) | (0.2387) | |

| Tec | −0.2381 ** | −0.3127 ** |

| (0.1035) | (0.1356) | |

| Eco | 1.0942 *** | 0.9639 ** |

| (0.3305) | (0.4419) | |

| Indu | −0.0526 *** | −0.1114 *** |

| (0.0136) | (0.0170) | |

| Urban | −0.5148 | −2.6266 * |

| (1.4219) | (1.4220) | |

| Labor | 3.8592 *** | 2.9803 *** |

| (0.6004) | (0.7153) | |

| Constant | 86.8812 *** | 92.3395 *** |

| (3.5035) | (4.4431) | |

| Observations | 3142 | 1533 |

| R-squared | 0.934 | 0.956 |

| between-group differences | 0.325 | |

| Variables | PSM-DID | Entropy Matching |

|---|---|---|

| WEE | WEE | |

| WET | 0.5243 *** | 0.4296 *** |

| (0.1428) | (0.1460) | |

| Tec | −0.3115 *** | −0.1415 |

| (0.0845) | (0.0965) | |

| Eco | 0.9606 *** | 0.7447 ** |

| (0.2749) | (0.3158) | |

| Indu | −0.0730 *** | −0.0714 *** |

| (0.0109) | (0.0121) | |

| Urba | −0.8896 | 0.9287 |

| (1.1127) | (1.3396) | |

| Labor | 3.9192 *** | 4.0566 *** |

| (0.4939) | (0.5644) | |

| Constant | 89.8789 *** | 89.1568 *** |

| (2.8322) | (3.2524) | |

| Observations | 4657 | 4675 |

| City | YES | YES |

| Year | YES | YES |

| R-squared | 0.939 | 0.938 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | Random Forest | Lasso Regression | Gradient Boosting | Neural Network | |

| WEE | WEE | WEE | WEE | WEE | |

| WET | 1.5998 *** | 1.6092 *** | 1.5792 *** | 1.6020 *** | 1.6327 *** |

| (0.1106) | (0.1107) | (0.1128) | (0.1112) | (0.1139) | |

| Constant | 0.0374 | 0.0399 | 0.0644 | 0.0570 | 0.0422 |

| (0.0620) | (0.0621) | (0.0623) | (0.0624) | (0.0624) | |

| Control variable terms | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Control variable quadratic term | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 4676 | 4676 | 4676 | 4676 | 4676 |

| Variables | Market | Wcb | Tec-Out |

|---|---|---|---|

| WEE | WEE | WEE | |

| WET | 0.3323 ** | 0.4589 ** | 2.1302 ** |

| (0.1618) | (0.2010) | (0.8985) | |

| market | −0.0168 * | ||

| (0.0087) | |||

| Market × WET | 0.0510 *** | ||

| (0.0197) | |||

| Wcb | −0.0258 *** | ||

| (0.0086) | |||

| Wcb × WET | 0.0227 ** | ||

| (0.0105) | |||

| Tec-out | −1.0154 *** | ||

| (0.1998) | |||

| Tec-out × WET | −0.1891 * | ||

| (0.1013) | |||

| Tec | −0.3077 *** | −0.4334 *** | −0.2710 *** |

| (0.0845) | (0.1105) | (0.0824) | |

| Eco | 0.9675 *** | 1.4301 *** | 1.1912 *** |

| (0.2757) | (0.3515) | (0.2791) | |

| Indu | −0.0743 *** | −0.0774 *** | −0.0710 *** |

| (0.0109) | (0.0124) | (0.0107) | |

| Urba | −0.9610 | −2.1091 | −0.9562 |

| (1.0965) | (1.3479) | (1.0632) | |

| Labor | 3.9416 *** | 3.5113 *** | 3.5098 *** |

| (0.4952) | (0.6006) | (0.4900) | |

| Constant | 89.8977 *** | 87.6278 *** | 96.1966 *** |

| (2.8491) | (3.4448) | (2.9754) | |

| Observations | 4675 | 3241 | 4675 |

| R-squared | 0.939 | 0.943 | 0.940 |

| LR test | SDM can be simplified to SAR | 232.91 *** | 0.000 | SDM |

| SDM can be simplified to SEM | 224.97 *** | 0.000 | SDM | |

| Wald test | SDM can be simplified to SAR | 150.82 *** | 0.000 | SDM |

| SDM can be simplified to SEM | 218.07 *** | 0.000 | SDM | |

| Hausman test | 25.55 *** | 0.000 | fixed effect | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Main | Wx | LR_Direct | LR_Indirect | LR_Total |

| WET | 0.4117 ** | 1.7946 ** | 0.4315 ** | 3.7229 *** | 4.1545 *** |

| (0.1695) | (0.7569) | (0.1712) | (1.3792) | (1.2953) | |

| Tec | −0.0870 | −4.3734 *** | −0.1205 ** | −8.3355 *** | −8.4560 *** |

| (0.0626) | (0.4176) | (0.0599) | (1.1400) | (1.1339) | |

| Eco | 0.3413 * | 10.1525 *** | 0.4335 ** | 19.5322 *** | 19.9658 *** |

| (0.1877) | (1.1150) | (0.1758) | (2.8308) | (2.7890) | |

| Indu | −0.0479 *** | −0.3782 *** | −0.0507 *** | −0.7514 *** | −0.8021 *** |

| (0.0076) | (0.0513) | (0.0074) | (0.1260) | (0.1249) | |

| Urba | 0.4287 | 15.6211 *** | 0.5367 | 29.4206 *** | 29.9574 *** |

| (0.5878) | (4.0085) | (0.5595) | (7.9813) | (7.9301) | |

| Labor | 3.4472 *** | −0.2848 | 3.4800 *** | 2.9540 | 6.4340 |

| WET | (0.3802) | (3.4467) | (0.3761) | (6.6663) | (6.6648) |

| ρ | 0.4690 *** | ||||

| (0.0699) | |||||

| sigma2_e | 3.5746 *** | ||||

| (0.0745) | |||||

| City | YES | ||||

| Year | YES | ||||

| Observations | 4878 | ||||

| R-squared | 0.109 | ||||

| Number of cityid | 271 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Du, P.; Du, J.; Liu, Q. Has the Water Rights Trading Policy Improved Water Resource Utilization Efficiency? Water 2025, 17, 3459. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243459

Du P, Du J, Liu Q. Has the Water Rights Trading Policy Improved Water Resource Utilization Efficiency? Water. 2025; 17(24):3459. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243459

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Pei, Juntao Du, and Qingqing Liu. 2025. "Has the Water Rights Trading Policy Improved Water Resource Utilization Efficiency?" Water 17, no. 24: 3459. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243459

APA StyleDu, P., Du, J., & Liu, Q. (2025). Has the Water Rights Trading Policy Improved Water Resource Utilization Efficiency? Water, 17(24), 3459. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243459