1. Introduction

Urban reservoirs play an important role in rainwater collection, groundwater recharge, flood control and drainage, agricultural irrigation, local climate regulation, and the maintenance of ecological balance. Urban reservoirs have become a critical link in ensuring public well-being, supporting sustainable urban development, and promoting harmonious coexistence between humans and nature [

1]. The upstream watershed of the reservoir serves as a critical water source for the reservoir area, playing an essential role in supplying water for production, domestic use, and ecological needs in the surrounding regions [

2]. Its water quality is directly related to the water quality and ecological stability of the downstream reservoir. Once the upstream water environment is polluted, it can not only compromise the water supply security of the downstream reservoir but also cause long-term impacts on the regional ecosystem. Therefore, ensuring the cleanliness and safety of water resources in the upstream watershed is a key measure for safeguarding the ecological security and sustainable use of urban reservoirs. However, with the continuous population growth, accelerated industrialization and urbanization, and the ongoing expansion of agricultural activities, the water quality in the upstream watershed of the reservoir is facing unprecedented challenges [

3]. Industrial point-source wastewater, domestic sewage generated by urban residents, and agricultural non-point-source pollution resulting from the use of fertilizers and pesticides during crop cultivation continuously enter the water bodies. These pollutants continuously introduce nitrogen, phosphorus, organic matter, and heavy metals into the upstream watershed, significantly increasing the concentration of contaminants in the water and posing a serious threat to water quality and ecological stability [

4]. Therefore, studying the water quality health status and the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of water quality in the upstream basin of the reservoir is of great theoretical value and practical significance for achieving refined management of the reservoir, identifying the main pollution sources in the reservoir area, and formulating scientifically effective control strategies.

Long-term water quality monitoring has accumulated a large amount of complex data with multiple sampling points, various indicators, and high-frequency characteristics, covering a wide range of water quality parameters including physical, chemical, and biological factors [

5]. How to effectively analyze and interpret the potential water quality characteristics still poses certain challenges. Commonly used water quality assessment methods mainly include the single-factor evaluation method, gray system evaluation method, fuzzy mathematics evaluation method, artificial neural network evaluation method, comprehensive water quality index (WQI) method, and multivariate statistical analysis [

6,

7,

8]. Among them, the Comprehensive Water Quality Index (WQI) method transforms multidimensional water quality parameters into a dimensionless single evaluation value, enabling a systematic representation of the overall condition of the aquatic environment. Compared with traditional single-factor evaluation methods, it offers greater comprehensiveness and intuitiveness. A study using the WQI method to assess river water quality in the Taihu Basin of China found that WQI can effectively evaluate water quality and its spatial variations [

9]. Another study applying the WQI method to evaluate water quality in the Middle Route of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project in China found that WQI can accurately reflect the seasonal and spatial variations in water quality [

10]. Multivariate statistical analysis methods, which are used to simplify data structures and extract latent information, have become important tools for analyzing water quality variation patterns and identifying potential pollution sources by uncovering the spatiotemporal relationships among water quality parameters. For example, a study used correlation analysis, principal component analysis, and cluster analysis to assess water quality in the Mahanadi River Basin in Odisha, India, revealing the main causes of water quality changes and providing data support for water quality protection and management in the basin [

11]. Another study, using the Keban Reservoir in Turkey as a case study, applied multivariate statistical methods such as discriminant analysis, principal component analysis, factor analysis, and cluster analysis to assess the seasonal and spatial variations in surface water quality of the reservoir. The study also identified the total phosphorus content in sediments, water types, and the trophic status of the reservoir, providing scientific evidence for water quality management of large reservoirs [

12]. However, the condition of the aquatic environment is influenced by both natural processes and human activities, making its assessment complex and variable. The application of multivariate statistical methods to multivariable water quality assessment has certain limitations when used in isolation. Therefore, it is often necessary to combine multiple multivariate statistical methods to minimize their individual limitations and comprehensively assess the spatial and temporal variations in water quality.

Guanting Reservoir is the first large-scale reservoir built after the founding of the People’s Republic of China and is an important and representative reservoir in North China. It controls a drainage area of 43,402 km

2, accounting for 92.8% of the total Yongding River basin area (46,768 km

2). As a multipurpose project, it serves functions such as flood control, water supply, power generation, and irrigation, and was once one of the main water sources for the capital, Beijing [

13]. Guanting Reservoir is part of the Yongding River system within the Hai River Basin. The basin spans from 112°8.3′ E to 116°20.6′ E and from 41°14.2′ N to 38°51′ N. It is located in a mid-latitude region characterized by a temperate semi-arid climate and a continental monsoon climate pattern. In the past decade or so, Guanting Reservoir has strengthened ecological environment management and protection across the entire basin, resulting in significant temporal and spatial changes in water quality within the reservoir area. However, most existing studies have focused on analyzing the temporal and spatial trends of water quality in the reservoir area, with relatively little attention given to the factors influencing water quality changes. In particular, there is a lack of systematic evaluation of water quality in the upstream watershed of the Guanting Reservoir, as well as in-depth analysis of the factors and pollution sources affecting upstream water quality. Therefore, it is urgent to analyze the spatial and temporal variations in water quality and the status of pollution sources in the upstream watershed, in order to provide a scientific basis for improving the water environmental quality and ecological service functions of the reservoir area. To gain a deeper understanding of the water quality health status, spatial and temporal distribution characteristics, and pollution sources in the upstream watershed of the Guanting Reservoir, this study analyzes monthly water quality monitoring data from nine monitoring stations located in the Hebei section of the upstream watershed in 2024. Eight key water quality indicators were selected, and an improved Comprehensive Water Quality Index (WQI) method was applied. This was combined with multivariate statistical analysis methods, including Cluster Analysis (CA), Discriminant Analysis (DA), Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and Factor Analysis (FA), to investigate the spatial and temporal characteristics of water quality in the upstream watershed of the Guanting Reservoir. This study aims to identify the dominant factors and potential pollution sources influencing the spatial and temporal variations in water quality, providing a scientific basis and technical support for the spatial-temporal management of water quality and environmental protection in the upstream watershed of the Guanting Reservoir and other similar watersheds.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Data

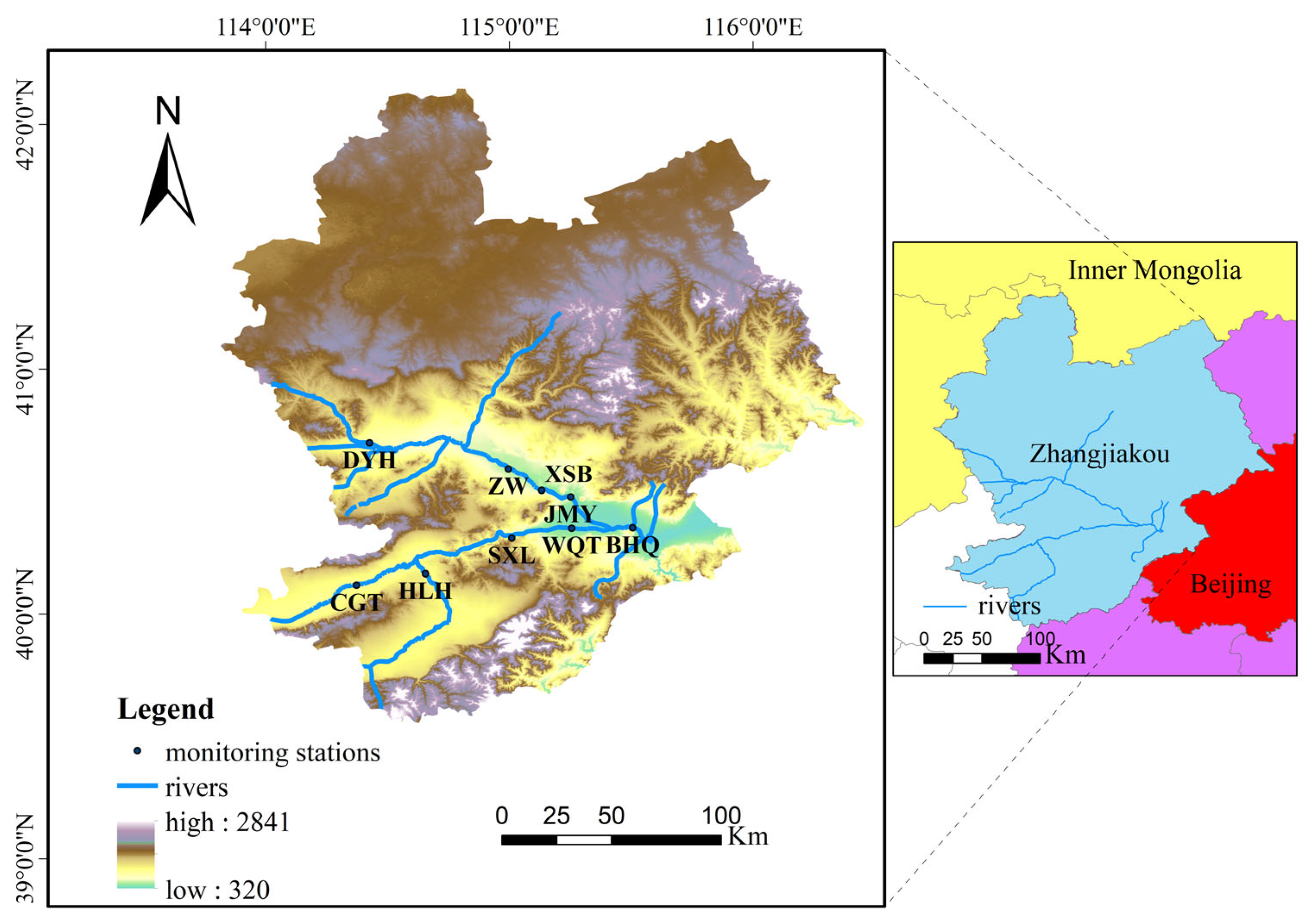

The upstream basin of the Guanting Reservoir includes two major tributaries, the Yang River and the Sanggan River, which are part of the Haihe River system [

14]. The Yang River and the Sanggan River converge at Zhuguantun in Huailai County, Zhangjiakou City, and are thereafter known as the Yongding River, which flows into the Guanting Reservoir and continues downstream into Beijing [

15]. The Yang River and the Sanggan River originate from Xinghe County in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and Ningwu County in Shanxi Province, respectively [

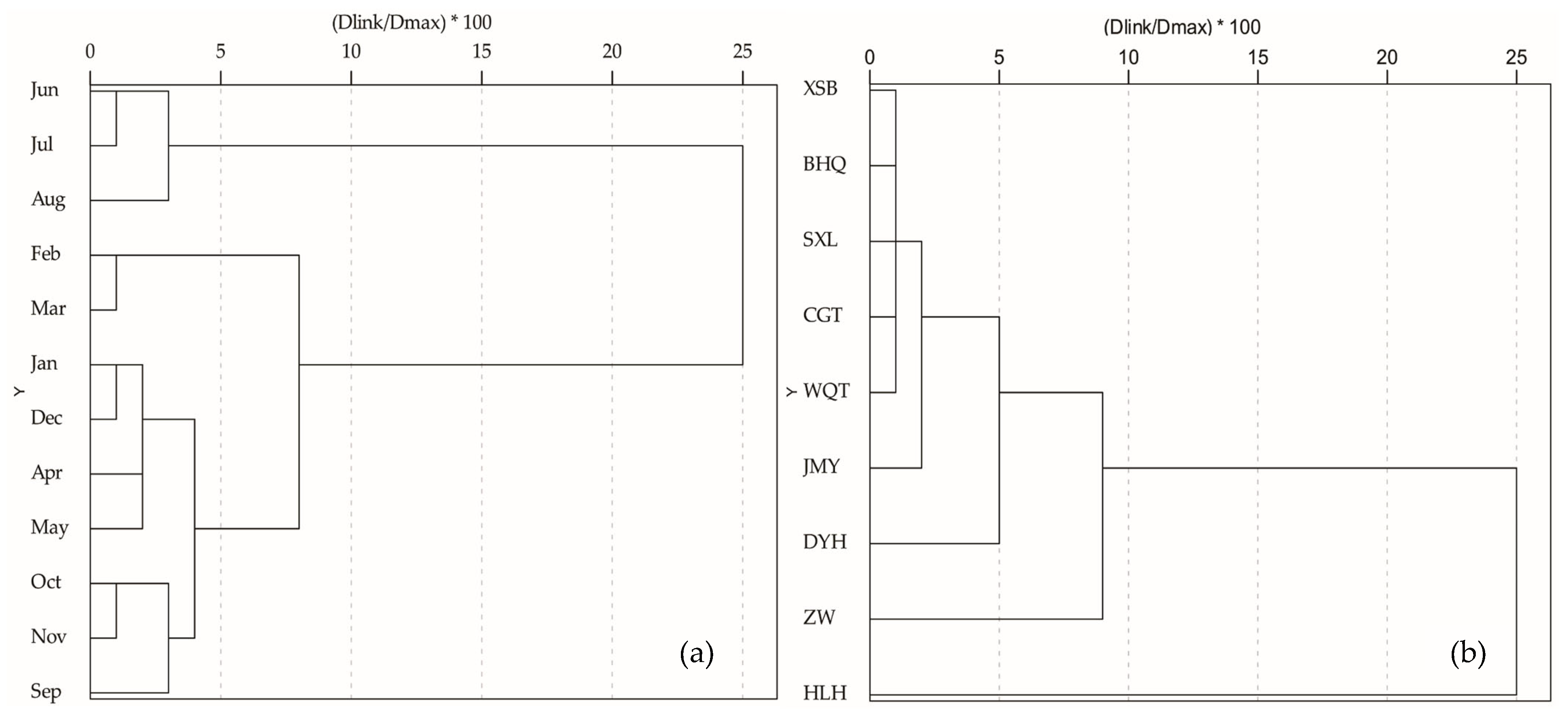

16]. The upstream region of the Guanting Reservoir has a typical temperate monsoon climate, with annual maximum temperatures reaching up to 40.9 °C, minimum temperatures dropping to −26.2 °C, and an average annual temperature of 7.8 °C. This paper focuses on the study of water quality in the upstream tributaries of the Guanting Reservoir located in Zhangjiakou City, Hebei Province, specifically the Dongyang River, Yang River, Sanggan River, and Huliu River. According to published studies within the same basin 16, about 80% of the annual precipitation in the Guanting Reservoir basin is concentrated in the summer months of June to August and early autumn months of September, which are clearly defined as the rainy season. Therefore, this study follows the climate characteristics of the region and defines June, July, and August (i.e., the core period of the rainy season) as the rainy season (WP) for subsequent discussions on seasonal differences and time clustering analysis. The remaining months are defined as the dry season (DP). A geographical overview of the area is shown in

Figure 1.

This study selected monthly water quality data from the year 2024 for nine key monitoring stations in the upstream basin of the Guanting Reservoir: Dongyang River (DYH), Zuo Wei (ZW), Xiangshuibao (XSB), Jimingyi (JMY), Bahao Bridge (BHQ), Chuaigutong (CGT), Shixiali (SXL), Wenquantun (WQT), and Hulu River (HLH). Among them, DYH is located in Hebei Province near Zhangjiakou City and is used to monitor upstream water quality. ZW, XSB, and JMY are situated along the Yang River, distributed sequentially from upstream to downstream, to monitor changes in the Yang River’s water quality. BHQ is located near the Guanting Reservoir and serves as a key station for monitoring reservoir water quality. SXL and CGT are positioned along the Sanggan River, also distributed from upstream to downstream, for monitoring water quality variations in the Sanggan River. WQT is located in the upper reaches of the Yongding River and is used to assess the water quality in that area. HLH, located on a tributary of the Sanggan River, is also an important station for monitoring the water quality of the reservoir. The eight water quality parameters selected for this study are: Total Nitrogen (TN), Total Phosphorus (TP), Ammonia Nitrogen (NH3-N), 5-Day Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD5), Dissolved Oxygen (DO), Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), Permanganate Index (CODMn), and Fluoride (F). The data used in this study were provided by the Guanting Reservoir Administration of Beijing.

During the water quality monitoring process, the layout of monitoring sites, sample collection, preservation and transportation, laboratory analysis, data compilation and processing, as well as quality assurance and control of the monitoring activities, were all conducted in strict accordance with the relevant requirements of the Technical Specifications for Monitoring of Surface Water and Wastewater (HJ/T 91-2002) [

17], issued by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. In addition, to improve the accuracy of the research results, the collected data were preprocessed prior to water quality assessment, including the handling of missing values and outliers. For certain water quality parameters that were missing at some stations but did not affect the overall data analysis, the missing values were omitted. A small number of outliers were handled in accordance with the Statistical Treatment and Interpretation of Data—Determination and Treatment of Outliers in Normal Samples (GB/T 4883-2008) [

18], issued by the Standardization Administration of China. The water quality data were analyzed in accordance with the Technical Specifications Requirements for Monitoring of Surface Water and Wastewater (Standard No. HJ/T 91-2002), issued by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China.

To understand the overall water quality status of the upstream region of the Guanting Reservoir within Hebei Province, this study employed an improved Water Quality Index (WQI) method to analyze the water quality data from various monitoring stations. The CA method was used to classify the water quality data in terms of spatial and temporal dimensions, in order to explore the characteristics of its spatiotemporal classification. Based on the results of CA, both the standard model and stepwise model methods in DA were employed to assess the accuracy of the spatiotemporal classification of the water quality data. The stepwise model was further used to identify effective water quality indicator variables that can distinguish between different spatiotemporal groups. PCA and FA methods were used to investigate the dominant factors and potential pollution sources contributing to the spatiotemporal variations in water quality in the upstream watershed of the Guanting Reservoir.

2.2. Improved Water Quality Index Method

The Water Quality Index (WQI) is a comprehensive method for assessing water quality. It reflects the overall condition of a water body by converting multiple water quality parameters—such as total nitrogen, total phosphorus, ammonia nitrogen, dissolved oxygen, biochemical oxygen demand, and potassium permanganate, etc.—into a single index value [

19]. This method simplifies the analysis and interpretation of water quality data, fully utilizes the information contained in water quality parameters, and provides a comprehensive reflection of the water quality condition. As a result, it allows non-experts to easily understand the water quality status and holds significant value in water resource management. Since the 1960s, the Water Quality Index (WQI) method has been widely applied in the assessment of both surface water and groundwater quality [

20].

When applying the WQI method to evaluate water quality data, the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is used to determine the weights. The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is a hierarchical weighting decision analysis method proposed by Professor Thomas L. Saaty, an operations researcher at the University of Pittsburgh. It commonly uses the traditional nine-point scale, which employs nine values (and their reciprocals) ranging from 1 to 9 to indicate the relative importance between evaluation elements. This process results in the formation of a judgment matrix and carries a degree of subjectivity [

21]. The

calculation formula for each water quality data point is as follows:

In the formula, n is the total number of water quality parameters; is the weight of the i-th water quality parameter calculated using AHP, with the sum of all equal to 1; is the normalized value of the i-th water quality parameter.

In response to the water quality management needs of rivers in the upstream watershed of the Guanting Reservoir in Beijing—taking into account both the protection of drinking water sources and the characteristics of agricultural non-point-source pollution—a normalization process was applied to each water quality parameter. This process was based on the national Environmental Quality Standards for Surface Water (GB3838-2002) and the water pollution prevention requirements of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, to ensure scientific and rational data processing. This national standard is the basic benchmark for water quality classification in China and serves as the basis for interpreting measurement data in this study. The weights and normalization details of each water quality parameter are presented in

Table 1.

2.3. Cluster Analysis

Cluster Analysis (CA) is an unsupervised learning method, meaning it does not require pre-labeled data for model training. It is used to group objects in a dataset such that objects within the same group (referred to as a “cluster”) have high similarity, while objects in different groups have low similarity. CA is a data classification method based on object similarity [

22]. In this study, Ward’s method combined with squared Euclidean distance was used for cluster analysis. A dendrogram was employed to classify and group water quality data with similar characteristics [

23]. In this study, temporal clustering was applied to divide the water quality data from the 12 months of the year into different monthly groups. Spatial clustering was applied to group the nine monitoring stations into different categories based on the similarity of the water quality data collected at each site. Spatiotemporal cluster analysis was conducted to explore the spatiotemporal characteristics of the water quality data. Based on the spatiotemporal clustering results, discriminant analysis, principal component analysis, and factor analysis were performed on the water quality data.

2.4. Discriminant Analysis

Discriminant Analysis (DA) is a supervised statistical method based on the results of cluster analysis. It assumes that the study objects have already been classified into several categories in some way, with each category characterized by a set of factors. The method aims to determine how a set of quantitative variables can be used to distinguish between these known categories [

24]. In this study, based on the results of spatiotemporal cluster analysis, both standard discriminant analysis and stepwise discriminant analysis were employed to perform the discriminant analysis [

25]. The standard discriminant analysis method uses all water quality parameters as independent variables without any selection. The stepwise discriminant analysis method, based on standard discriminant analysis, selects the most statistically significant independent variables with strong discriminative power from all water quality parameters for analysis. Discriminant analysis was used to examine the accuracy of the spatiotemporal classification results of the water quality data and to explore the characteristics of its spatiotemporal variations.

2.5. Principal Component Analysis and Factor Analysis

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a commonly used linear dimensionality reduction technique. Its purpose is to project data from a high-dimensional space to a lower-dimensional space through linear transformation while preserving as much of the original data’s variation as possible [

26]. Factor Analysis (FA) is a statistical technique that is typically conducted after Principal Component Analysis. It reduces the dimensionality of data by appropriately categorizing a large number of variables. In this process, it extracts factors that can represent the common variation in multiple original variables. The core concept of this method is to reveal and reflect the information contained in the original variables by identifying and utilizing these representative factors [

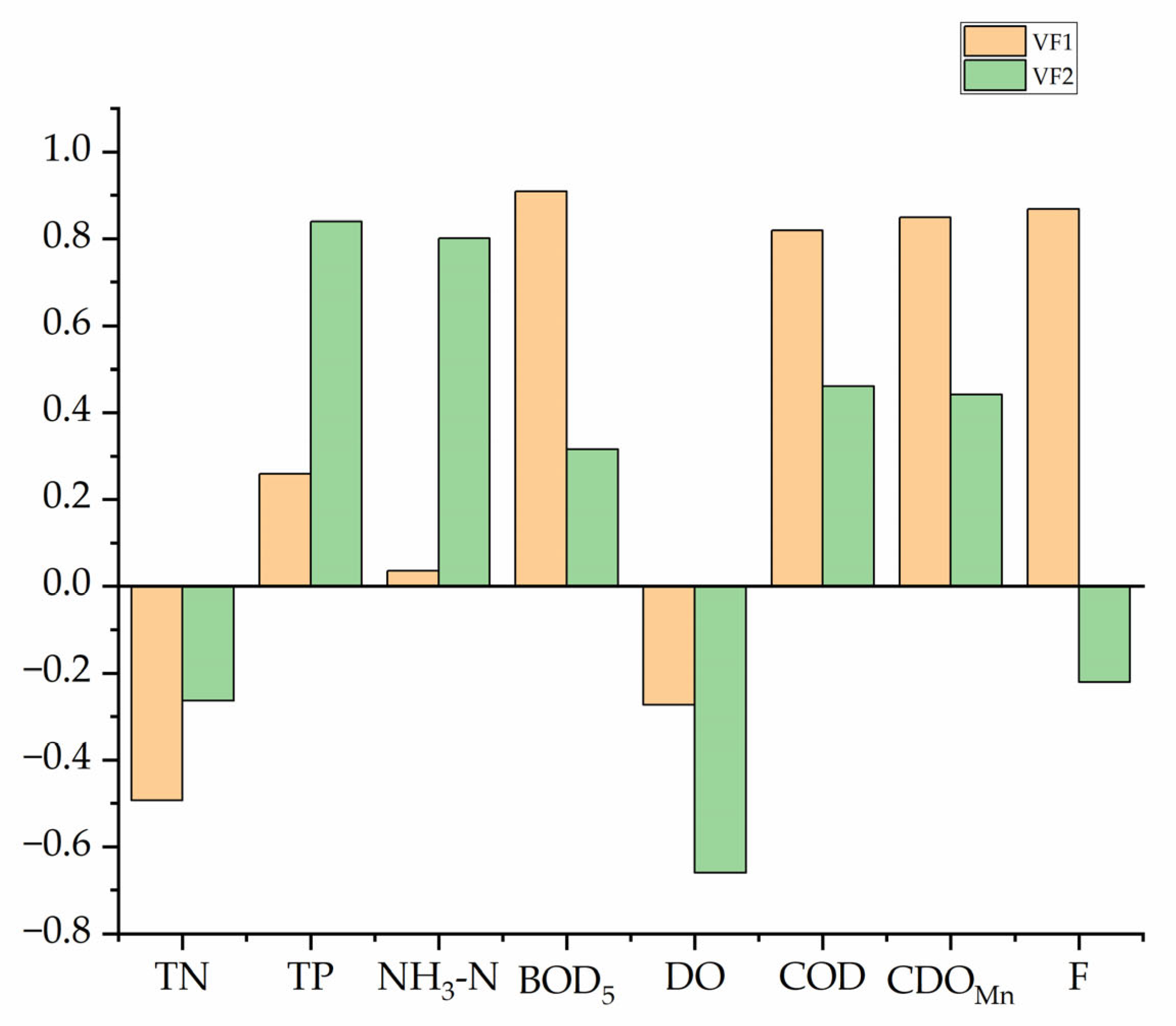

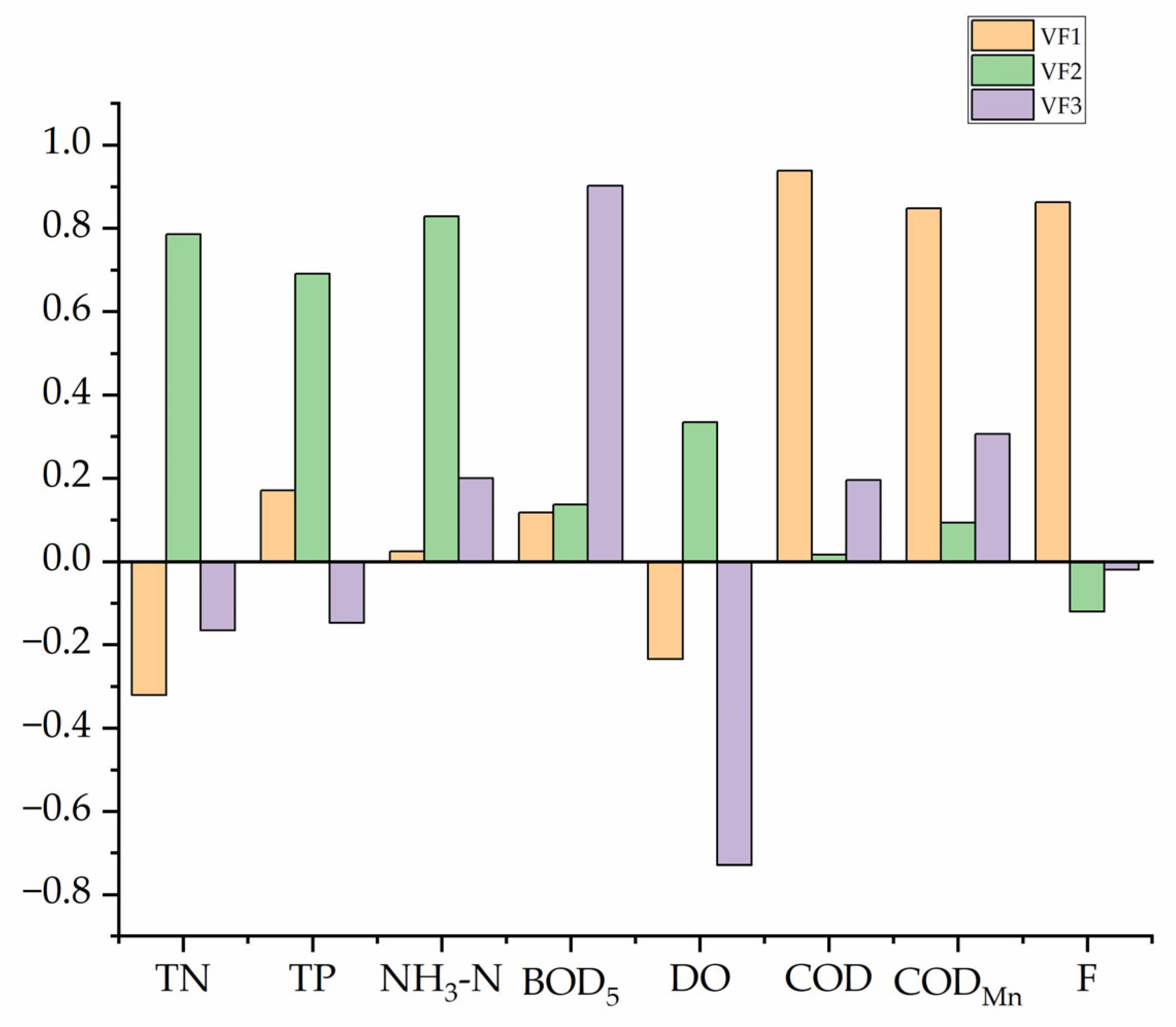

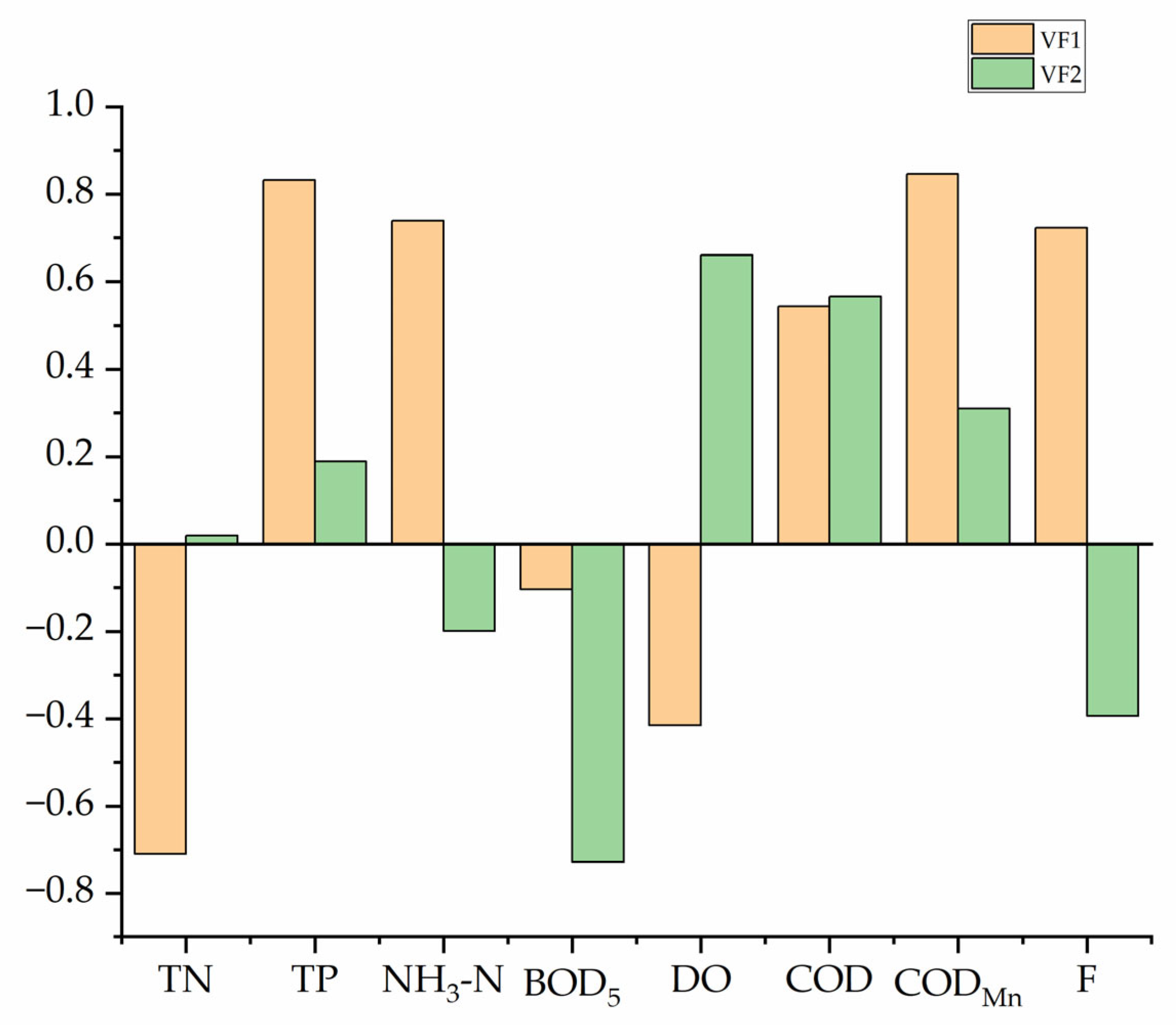

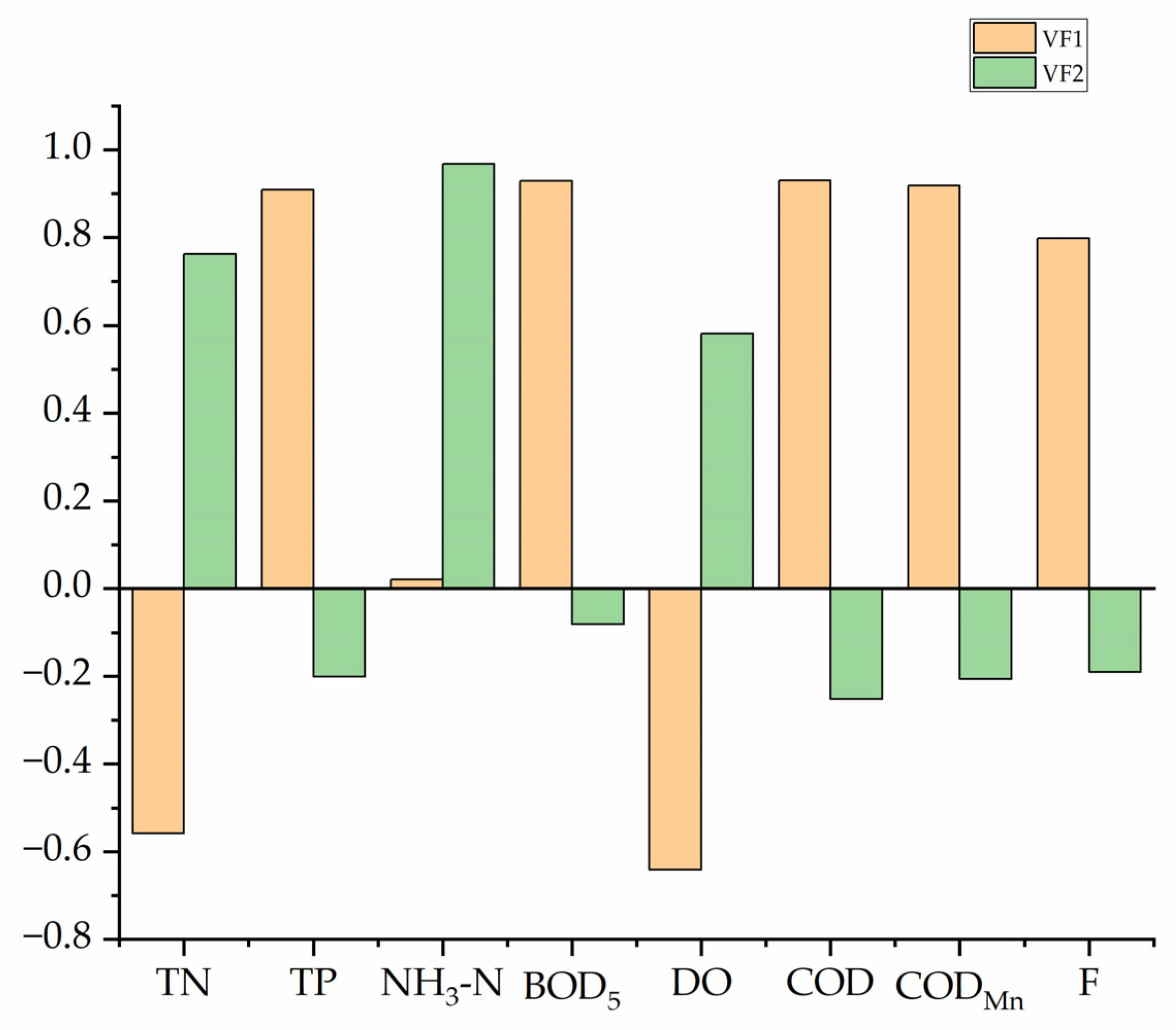

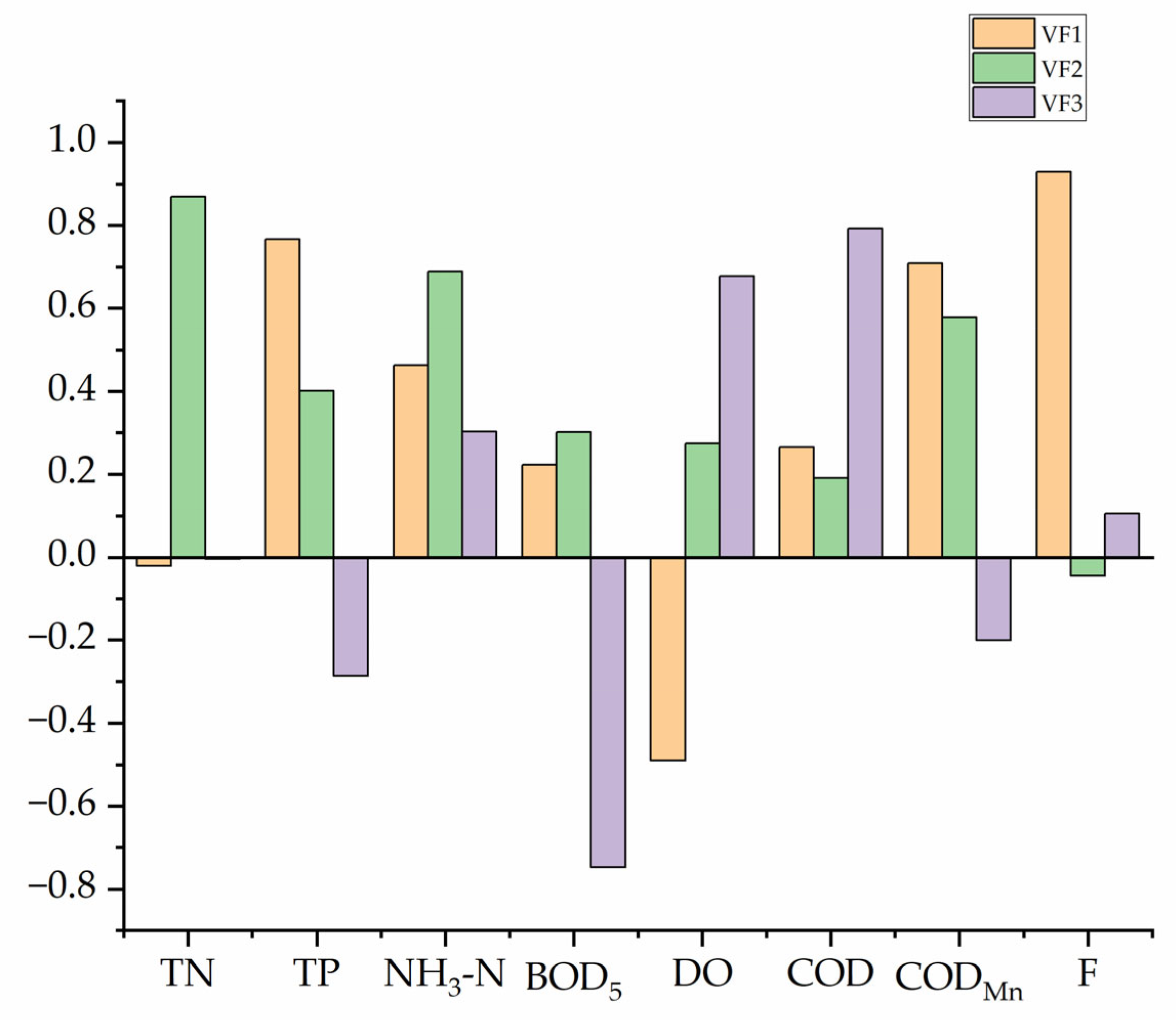

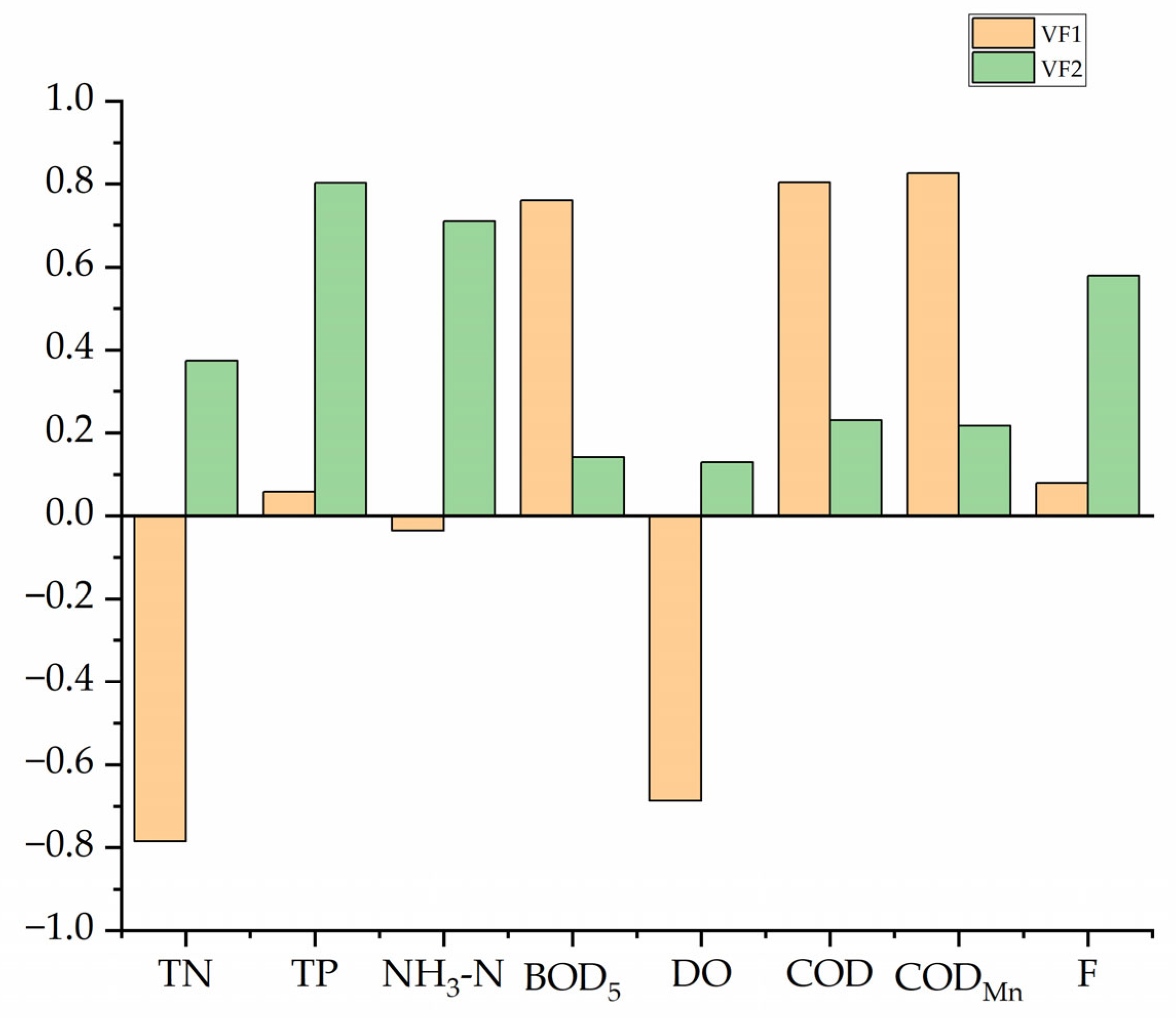

27]. In this study, based on the results of spatiotemporal cluster analysis, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Factor Analysis (FA) were performed on the temporal and spatial groups identified through cluster analysis. For each group, components with eigenvalues greater than 1 were retained to explore the dominant factors and potential pollution sources responsible for the spatiotemporal variations in the water quality data.

5. Conclusions

This study comprehensively applies the improved water quality index method and multivariate statistical analysis method to systematically reveal the spatiotemporal evolution law, dominant driving factors, and potential pollution sources of water quality in the upstream watershed of Guanting Reservoir in 2024. The main comprehensive conclusions are as follows:

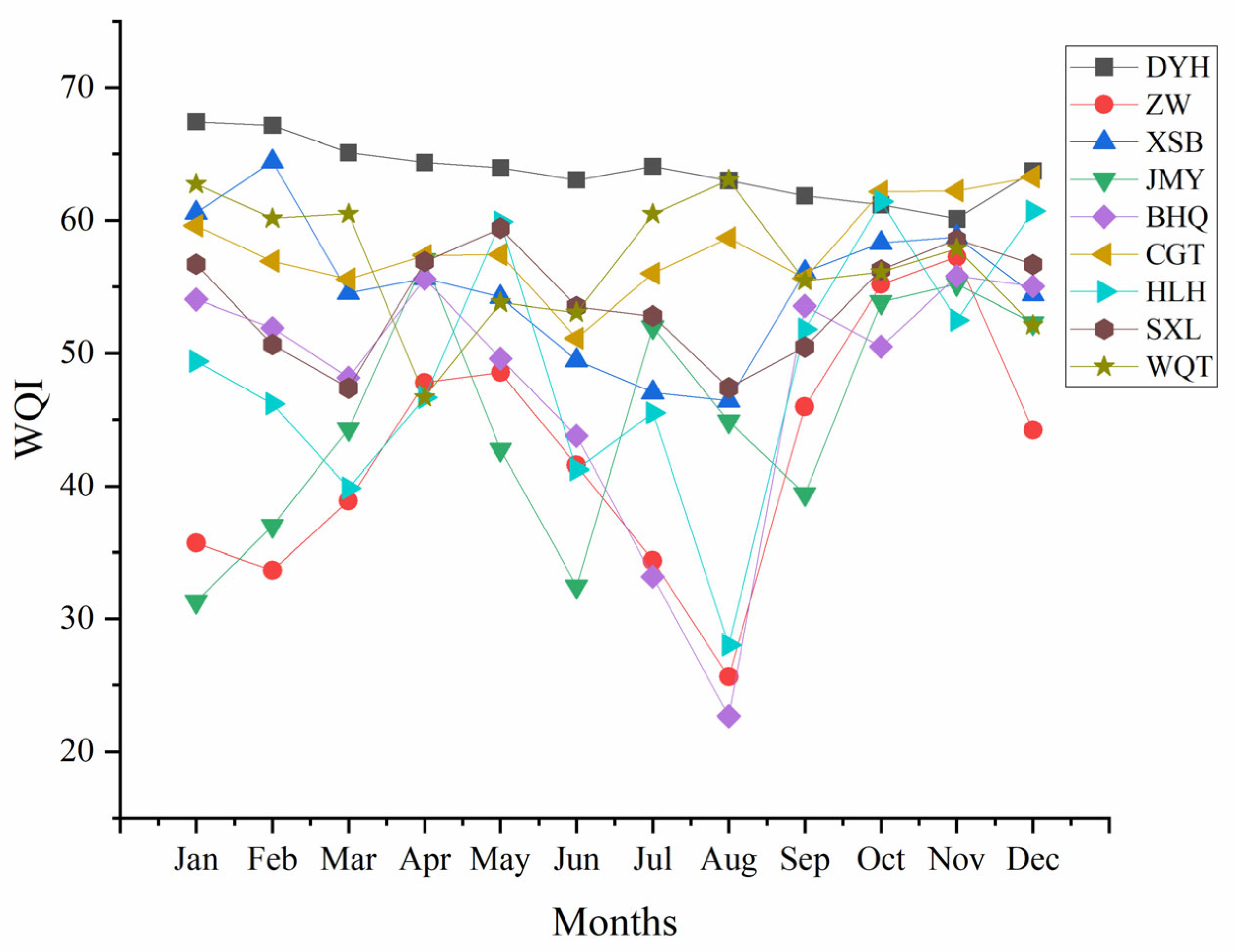

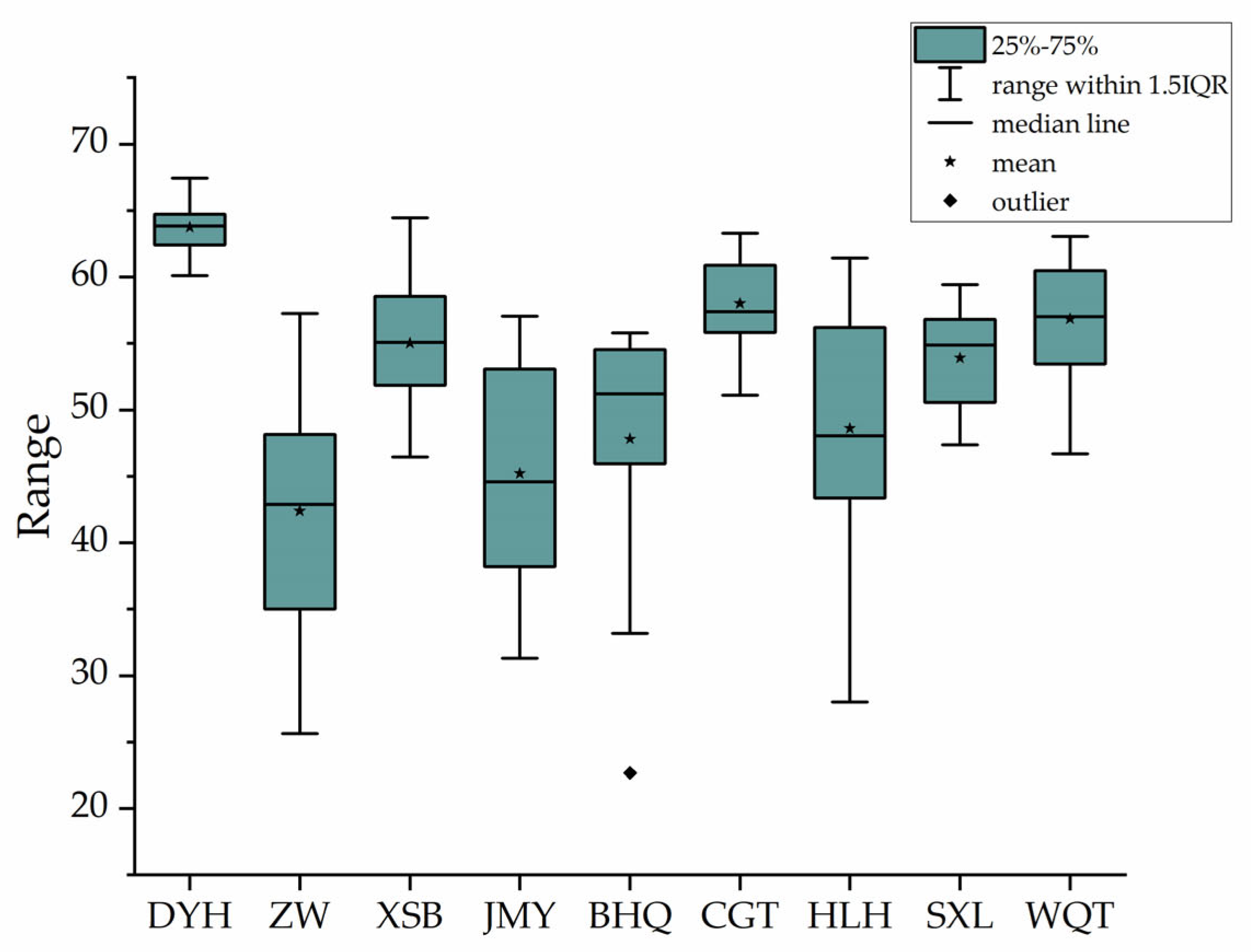

- (1)

The water quality of the watershed is sensitive to rainfall response, and the pollution input flux is the key to dominant temporal differentiation. Although rainfall has a certain dilution effect, this study found that the summer rainy season (June August) is the worst period for water quality throughout the year. This profoundly reveals that in semi-arid watersheds such as the upstream of Guanting Reservoir, which are strongly influenced by human activities, the pollution migration flux driven by rainfall runoff increases, and the negative effects caused by it systematically exceed the physical dilution effect of rainfall itself. This discovery revises the traditional belief that ‘water quality will inevitably improve during the rainy season’ in such areas and emphasizes the extreme importance of non-point-source pollution control in rainy season management. After the rainy season (starting from September), the water quality tends to stabilize and improve, which confirms that the self-purification ability of water bodies can be effectively exerted after the reduction in pollution input, further proving that controlling external input is the fundamental way to improve water quality.

- (2)

The clear spatial differentiation pattern of water quality confirms the basin pollution pattern of “human activity pressure accumulating downstream along the river network and estuary”. Spatial analysis clearly depicts a continuum from a relatively clean state upstream to severe pollution downstream. The water quality at the upstream DYH station is the best, reflecting the baseline state of the background environment. The significant deterioration of water quality at middle and downstream stations (such as ZW and BHQ) directly reflects the migration, mixing, and aggregation of pollution loads generated by human activities such as industry, agriculture, and residential life in the river network. In particular, the BHQ station, which serves as the direct “gateway” to the reservoir, has poor water quality, highlighting the vulnerability of the estuary area as a pollutant “sink” and posing the most direct and serious threat to the overall water quality of the reservoir.

- (3)

The analysis of pollution sources reveals the composite pollution characteristics of “point surface combination”, indicating the target of differentiated control. The comprehensive analysis of time and space shows that organic pollution and nutrient pollution are the two core issues that run through the entire basin and time period. However, there are temporal and spatial differences in the priority and sources of their contributions: In terms of time, the pollution during the rainy season is more reflected in the composite pollution carried by agricultural non-point sources and urban runoff; the dry season, on the other hand, is more prominently manifested as the sustained pressure of point-source emissions from daily life and industry. In terms of space, there are significant differences in the dominant pollution sources in different subregions, such as the mixed pollution of daily life and agriculture at the ZW station and the agricultural non-point-source pollution characteristics at the HLH station. This accurately depicts the complexity and diversity of pollution sources within the watershed.

Comprehensive management insights: The conclusion of this study indicates that a refined strategy of “spatiotemporal dual control and source sink linkage” must be adopted for water quality management in the upstream watershed of Guanting Reservoir. In terms of time, an emergency plan for pollution prevention and control should be developed for the rainy season, with a focus on strengthening the interception and buffering of source pollution. In terms of space, differentiated control measures based on sub-basin units must be implemented to reduce emissions at the source in key polluted areas such as ZW in the upper and middle reaches, and ecological restoration and enhanced purification must be carried out at the reservoir inlet (BHQ) to cut off the final channel for pollutants to enter the reservoir. Only by accurately directing limited governance resources towards key temporal and spatial nodes and dominant pollution sources can the water environment quality and ecological security level of the upstream watershed of Guanting Reservoir be fundamentally improved.