Bridging Uncertainty in SWMM Model Calibration: A Bayesian Analysis of Optimal Rainfall Selection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

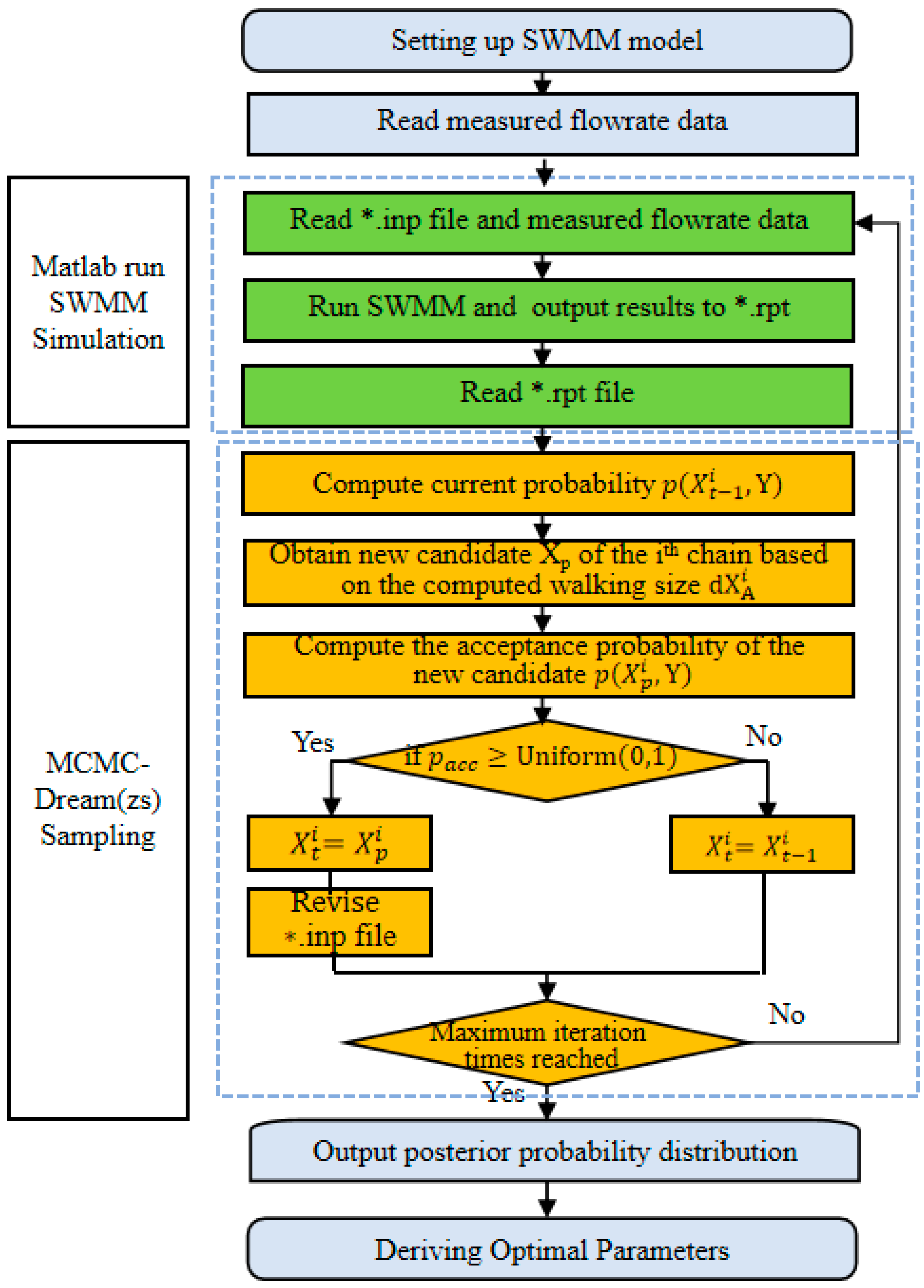

2.1. Framework of Bayesian DREAM(zs) SWMM Calibration

- (1)

- Validation of Bayesian DREAM(zs) algorithm

- (2)

- Monitoring data and “true” solution generation

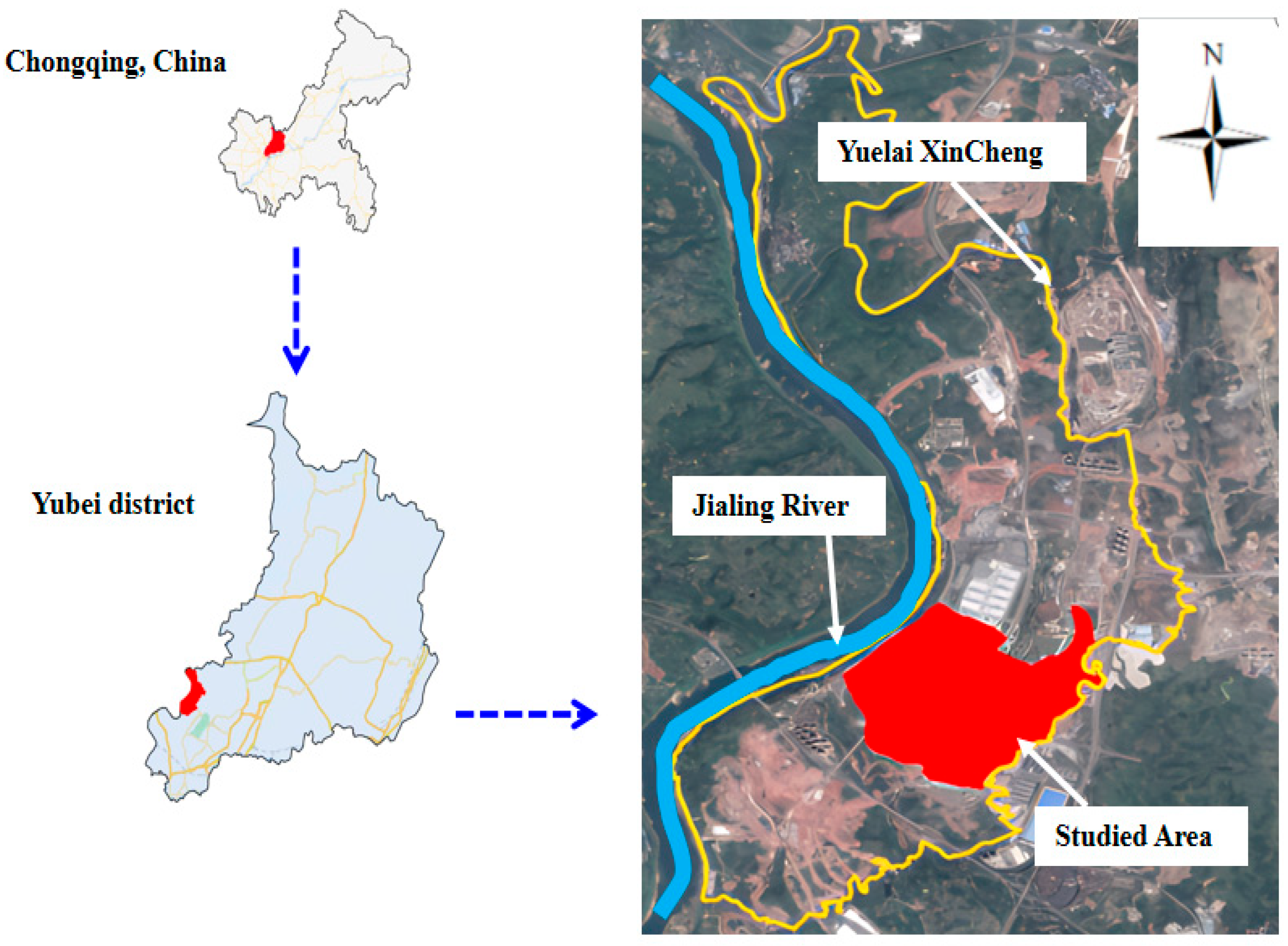

2.2. Case Study Area

2.3. SWMM Model Parameters

2.4. Factors Impacting Calibration

- (1)

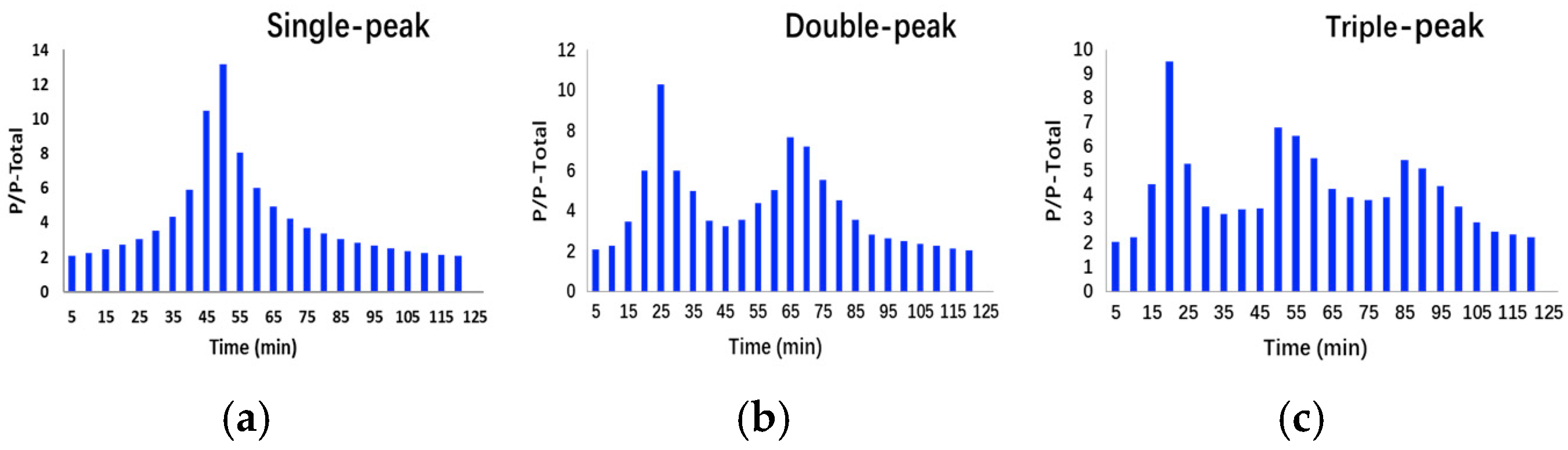

- Rainfall types

- (2)

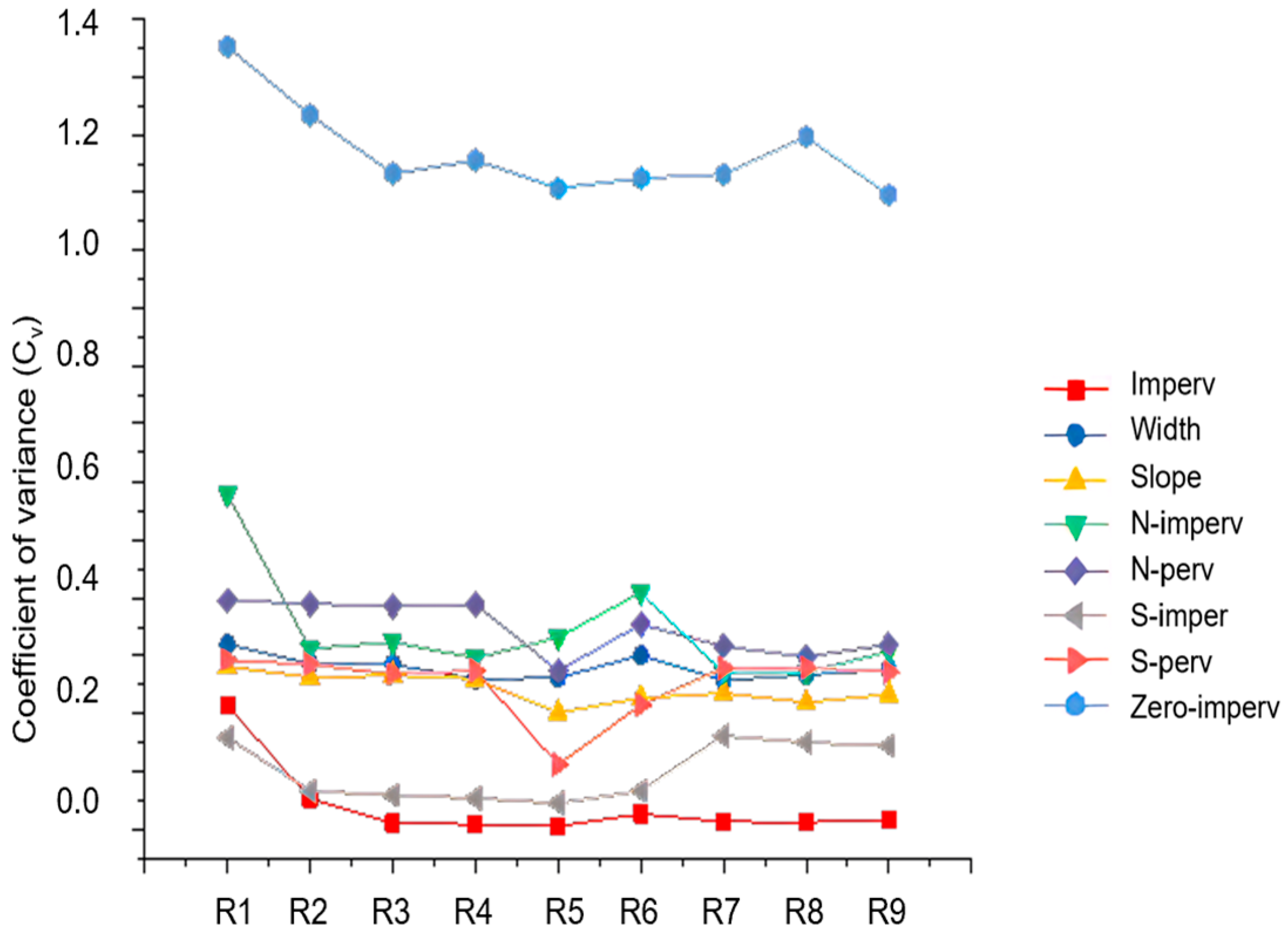

- Watershed hydrological characteristics

2.5. Bayesian Inference and DREAM(zs) Sampling

2.6. Calibration Performance Indicators

- (1)

- Criteria of Convergence

- (2)

- Accuracy of calibrated parameters

3. Results and Discussion

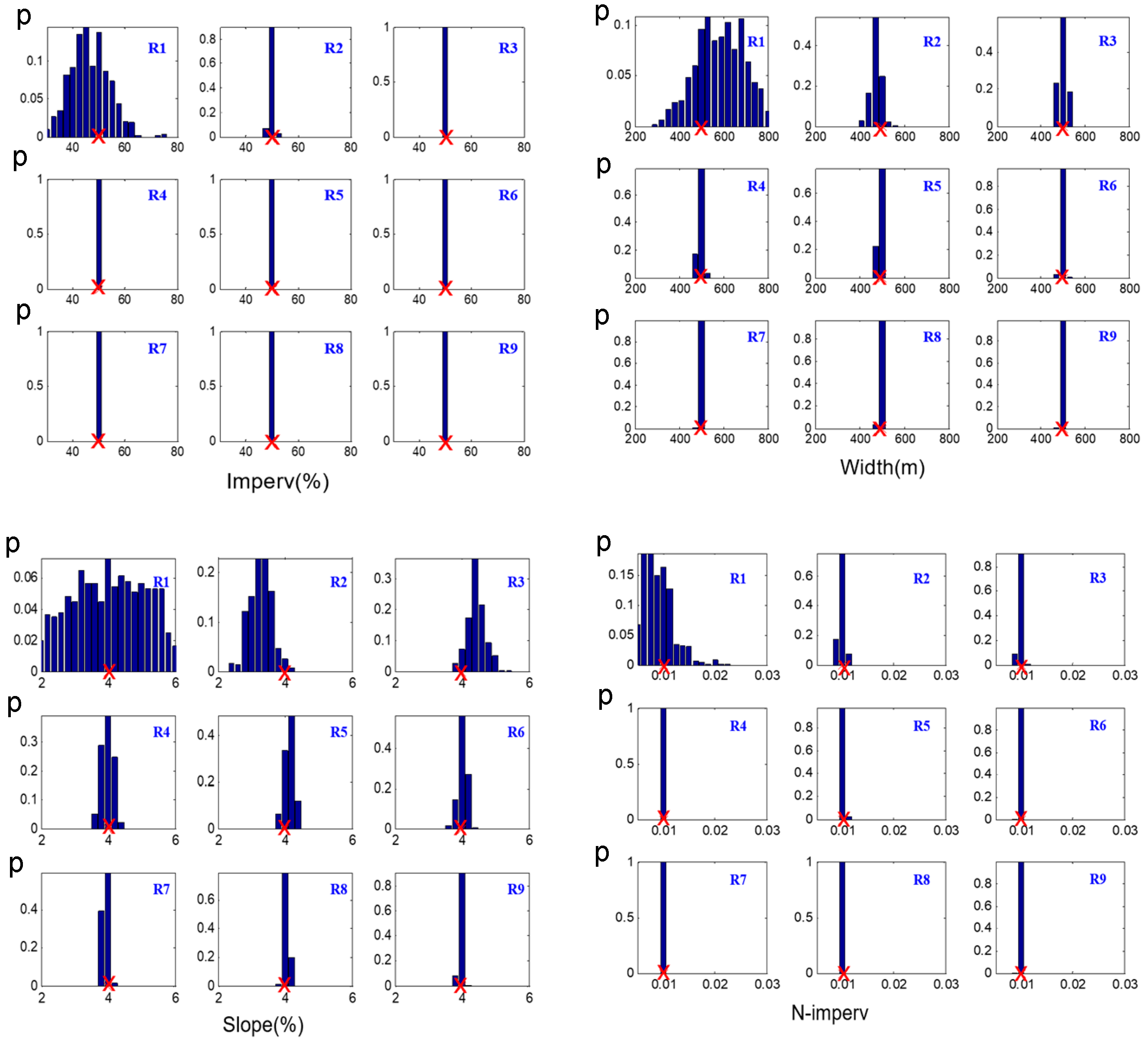

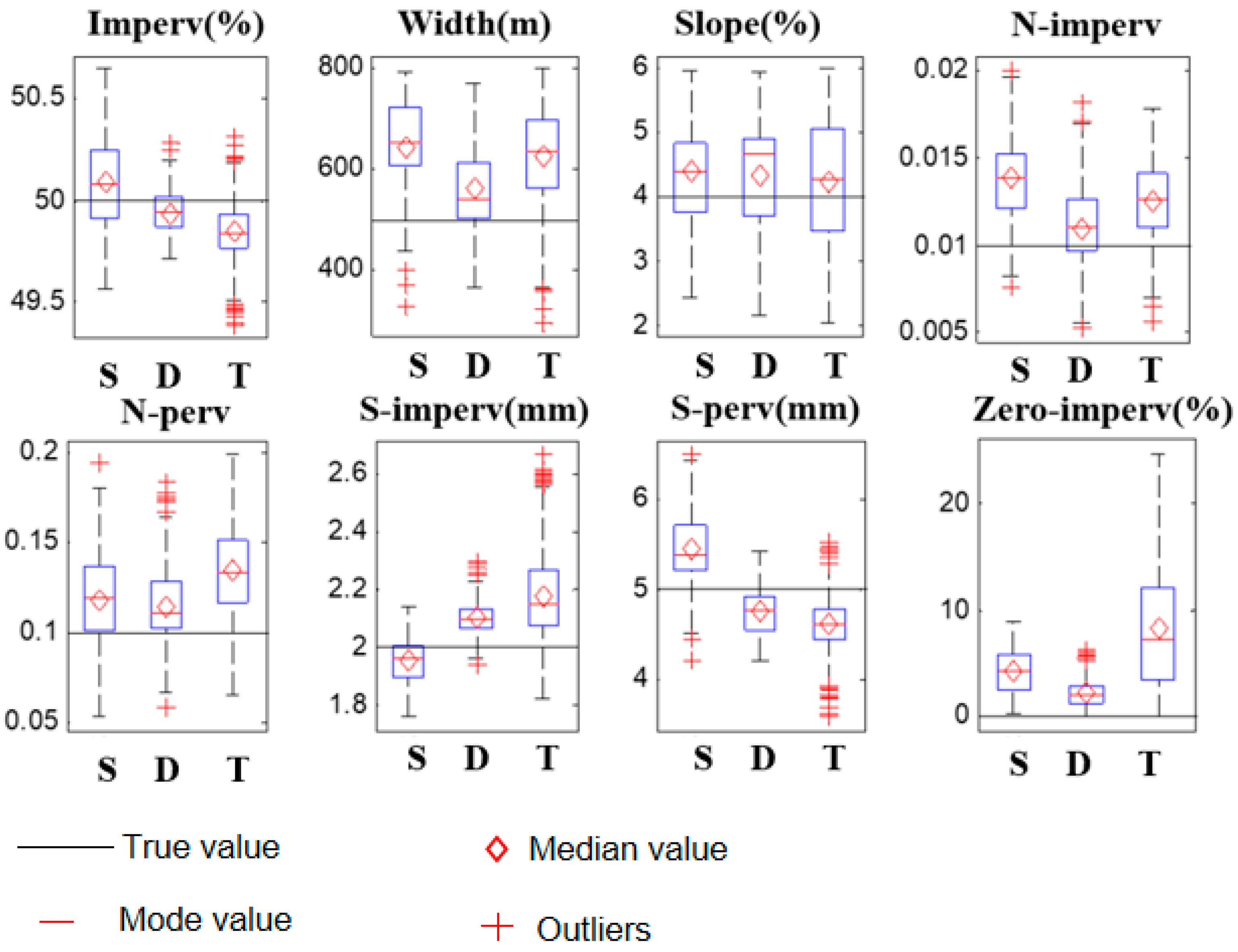

3.1. Identifying the Optimal Rainfall Intensity for Robust SWMM Calibration

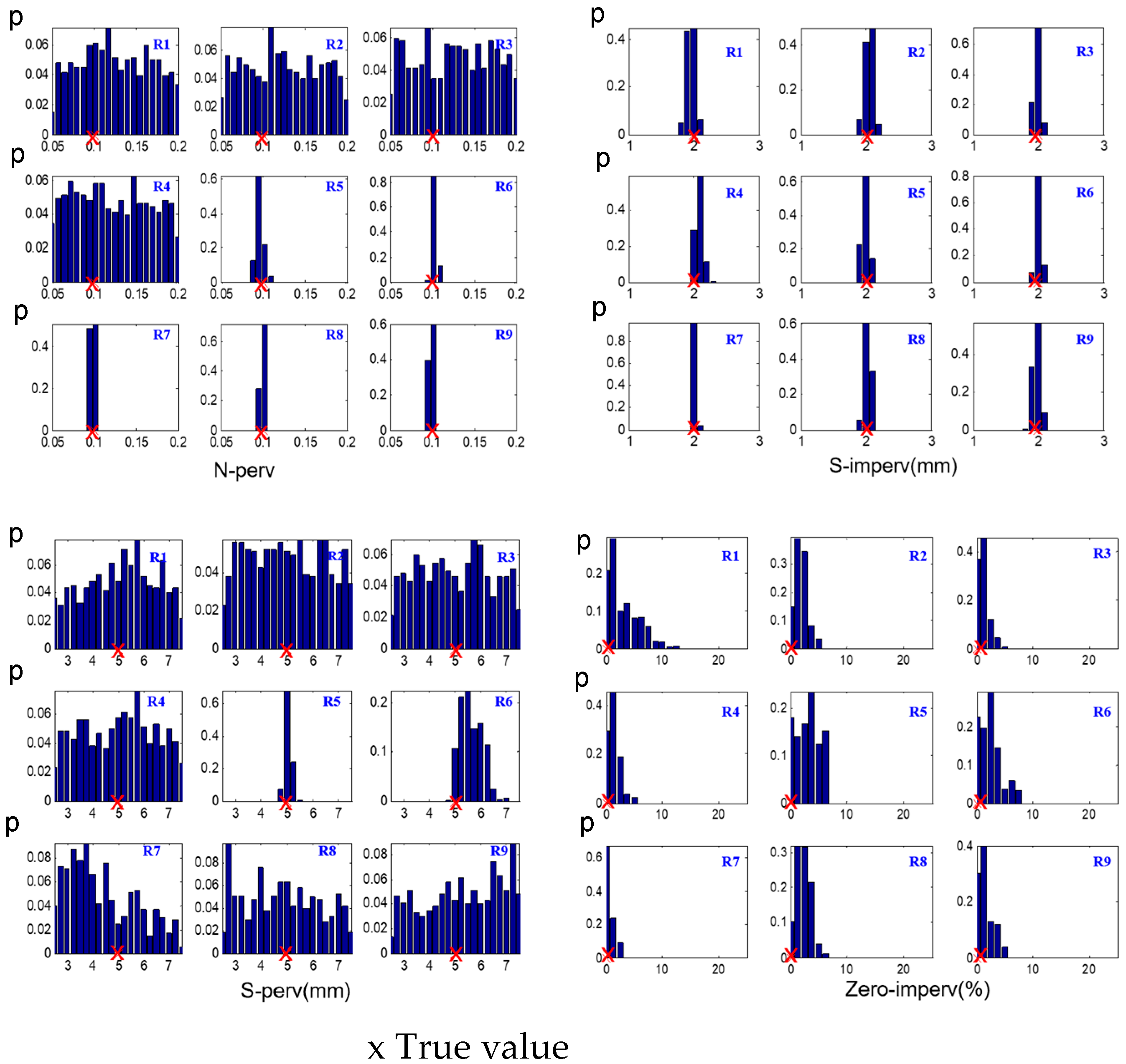

3.2. Impacts of Rainfall Pattern

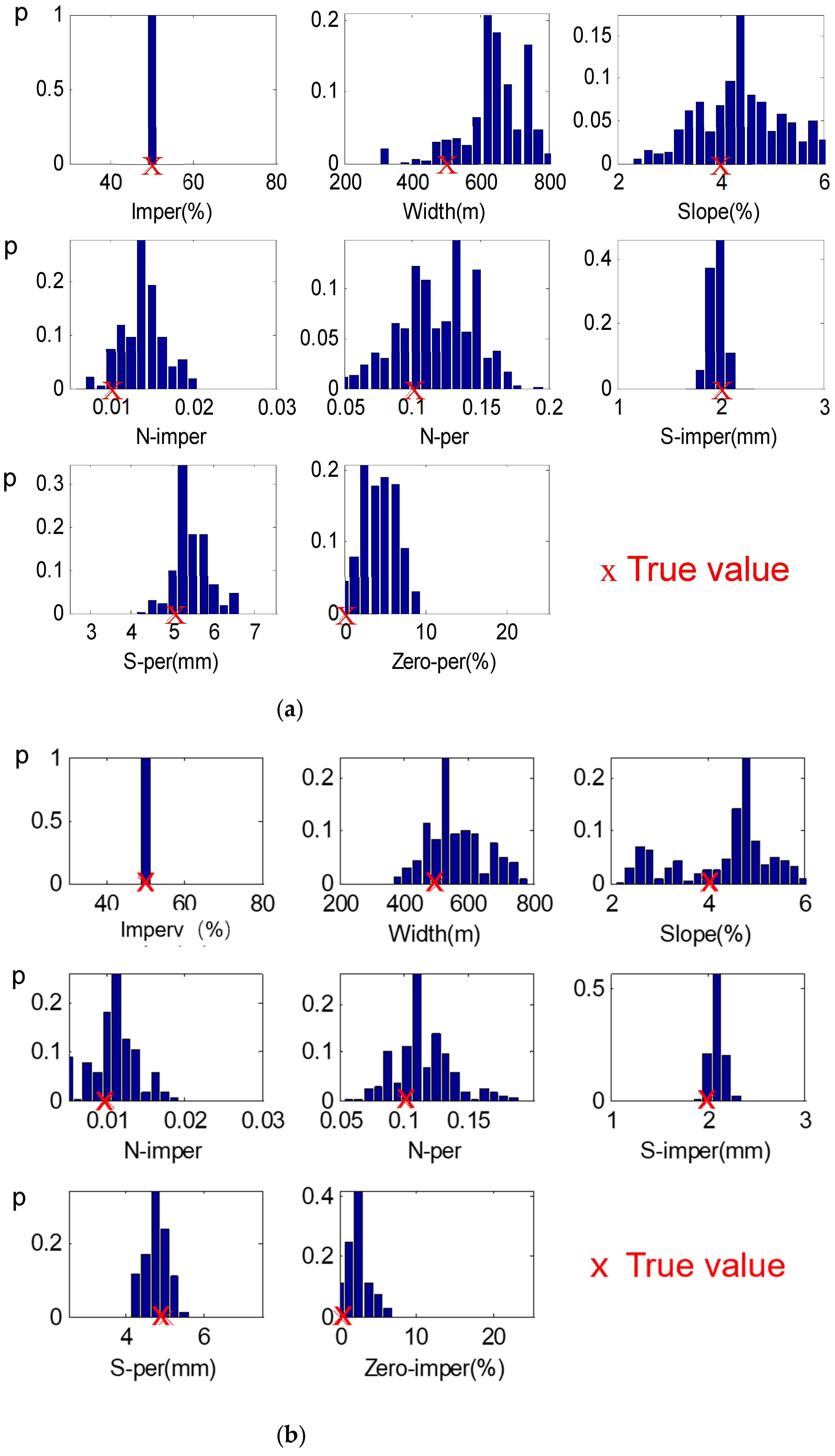

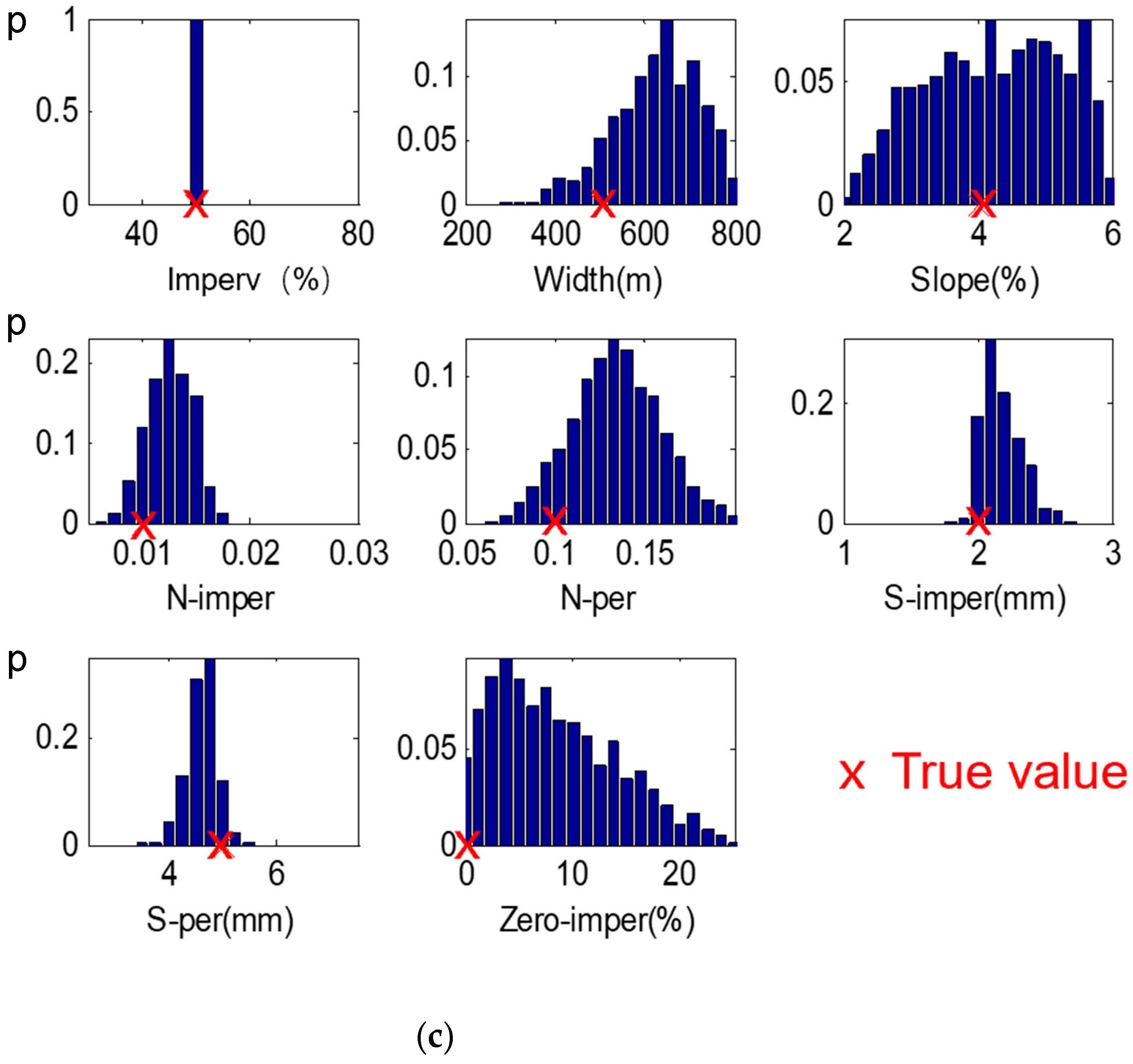

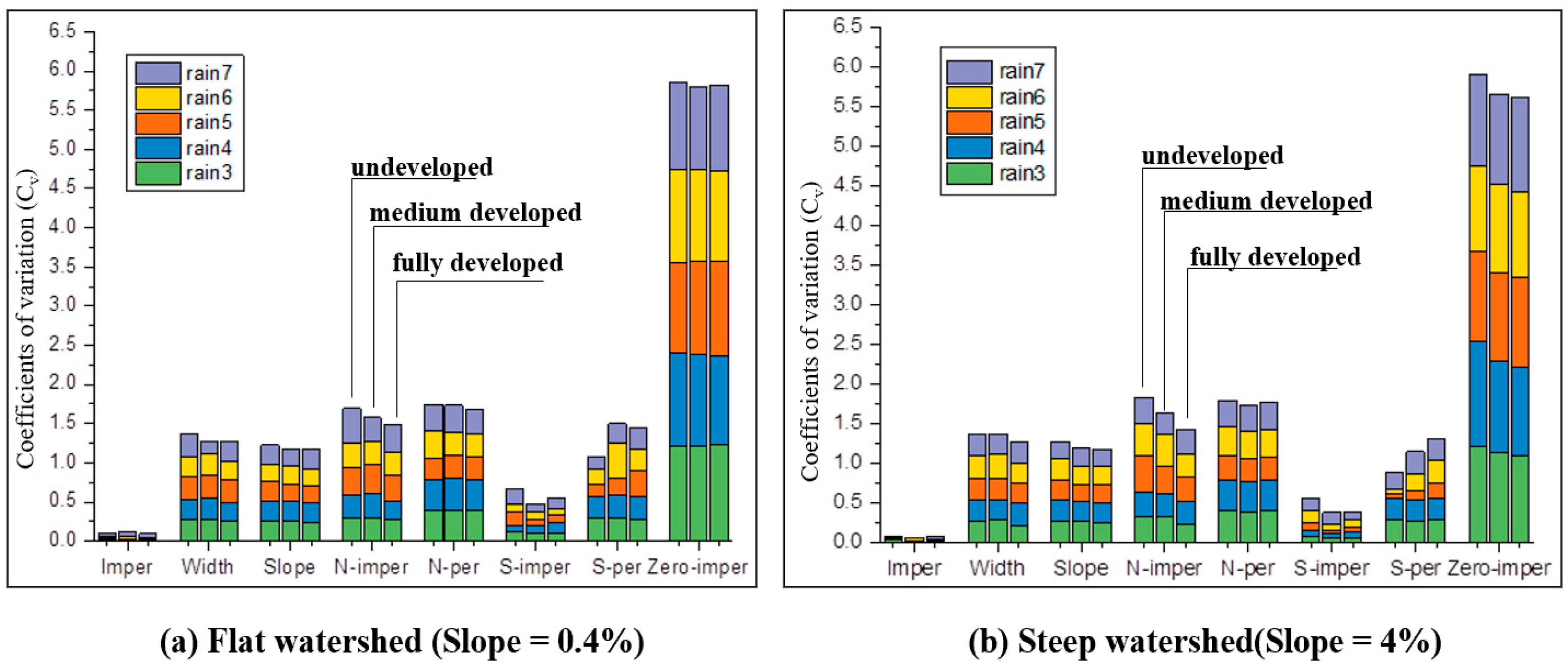

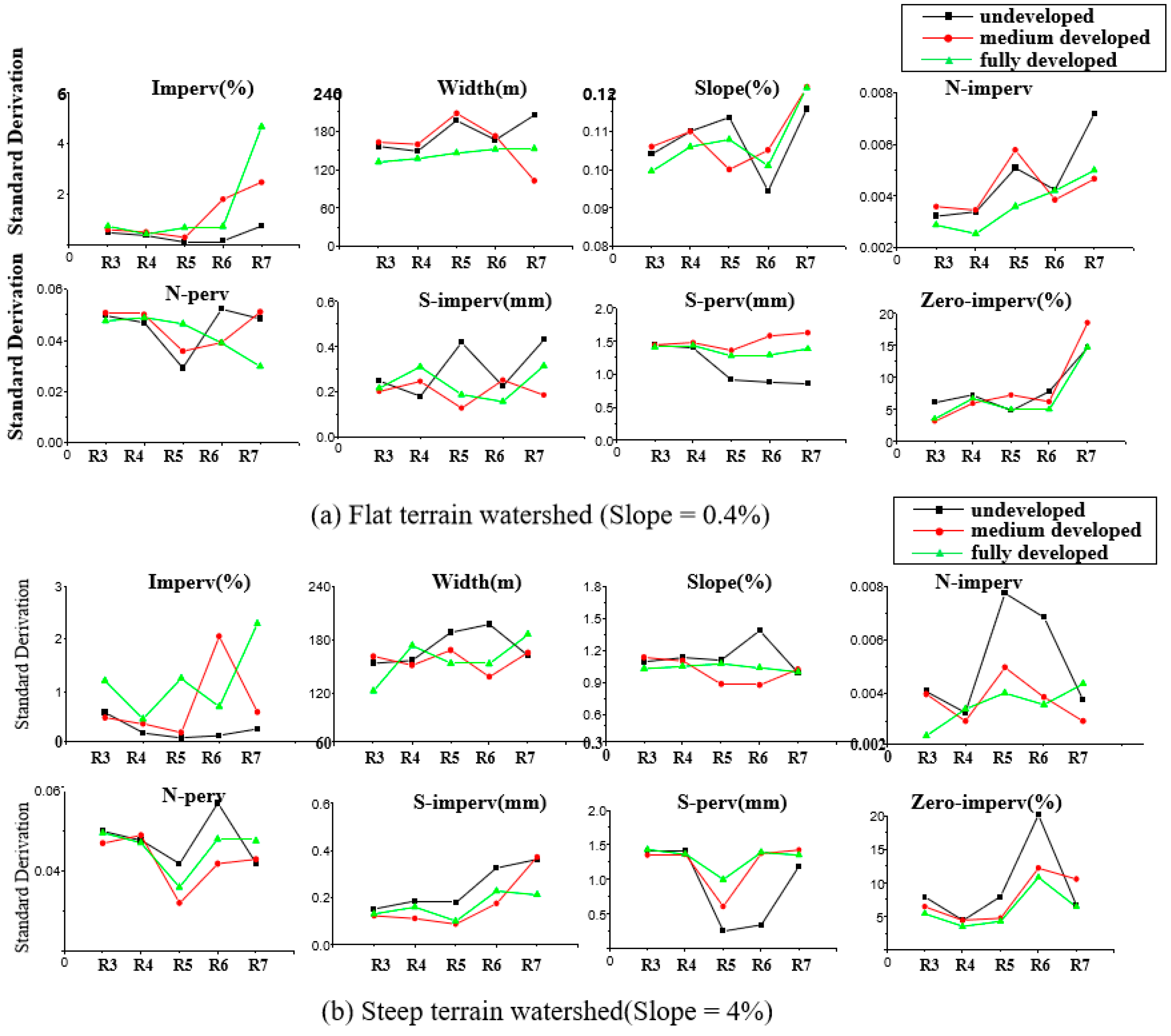

3.3. Impacts of Watershed Hydrological Characteristics

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Rainfall data with a medium intensity equivalent to a one-year return period (R5, total depth of 42.70 mm) or higher generally yielded the most satisfactory parameter accuracy. Compared to low-intensity rainfalls (e.g., R1), using the R5 rainfall reduced the posterior distribution standard deviations for most parameters by 40% to 60%. Notably, the parameters Imperv, S-imperv, and N-imperv exhibited minimal sensitivity to rainfall intensity variations, maintaining high accuracy across all scenarios (e.g., Imperv’s coefficient of variation remained below 0.005). The difficulty of achieving accurate calibration for all parameters, ranked from easiest to most challenging based on their posterior distribution coefficients of variation, was as follows: Imperv (Cv ≈ 0.005) < S-imperv (Cv ≈ 0.045) < S-perv (Cv ≈ 0.112) < Slope (Cv ≈ 0.202) < Width (Cv ≈ 0.262) < N-imperv (Cv ≈ 0.332) < N-perv (Cv ≈ 0.274) < Zero-imperv (Cv ≈ 1.108).

- (2)

- The double-peak rainfall pattern produced the most satisfactory calibration results. It was particularly effective in distinguishing between strongly correlated parameters like Width and Slope. Quantitatively, using the double-peak pattern reduced the standard deviation of the Width parameter from 168.647 m (single-peak) to 110.789 m, an improvement of approximately 34%. Similarly, the standard deviation of N-perv decreased from 0.032 to 0.021.

- (3)

- Watershed hydrological characteristics (terrain and development level) exhibited a negligible influence on parameter calibration accuracy once an optimal rainfall event (intensity and pattern) was selected. The differences in performance metrics (e.g., coefficient of variation) across different watershed types were minimal. For instance, the coefficient of variation for the key parameter Imperv remained in a narrow range (0.004 to 0.007) regardless of watershed type or rainfall intensity, confirming that watershed characteristics are not a dominant factor.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Abbreviations: | |

| SWMM | Storm Water Management Model |

| DREAM(zs) | Differential Evolution Adaptive Metropolis, Version ZS |

| MCMC | Markov Chain Monte Carlo |

| GLUE | Generalized Likelihood Uncertainty Estimation |

| IDF | Intensity–Duration–Frequency |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| NSE | Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency Coefficient |

| PBIAS | Percentage Bias |

| Cv | Coefficient of Variation |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| p | Probability Density |

| SWMM Model Parameters: | |

| Imperv | Percent of impervious area (%) |

| Width | Width of overland flow path (m) |

| Slope | Average slope of the sub-catchment (%) |

| N-imperv | Manning’s roughness coefficient for impervious areas |

| N-perv | Manning’s roughness coefficient for pervious areas |

| S-imperv | Depression storage depth for impervious areas (mm) |

| S-perv | Depression storage depth for pervious areas (mm) |

| Zero-imperv | Percent of impervious area with no depression storage (%) |

References

- Aqil, M.; Kita, I.; Yano, A.; Nishiyama, S. Analysis and prediction of flow from local source in a river basin using a Neuro-fuzzy modeling tool. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 85, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzellino, A.; Cevirgen, S.; Giupponi, C.; Parati, P.; Ragusa, F.; Salvetti, R. SWAT meta-modeling as support of the management scenario analysis in large watersheds. Water Sci. Technol. 2015, 72, 2103–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.E.; Fang, T. Evaluation of spatially variable control parameters in a complex catchment modelling system: A genetic algorithm application. J. Hydroinformatics 2007, 9, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barco, J.; Wong, K.M.; Stenstrom, M.K. Automatic Calibration of the U.S. EPA SWMM Model for a Large Urban Catchment. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2008, 134, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beven, K.; Binley, A. The future of distributed models-model calibration and uncertainty prediction. Hydrol. Process. 1992, 6, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beven, K.; Freer, J. Equifinality, data assimilation, and uncertainty estimation in mechanistic modelling of complex environmental systems using the GLUE methodology. J. Hydrol. 2001, 249, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Ye, M. Variance-based global sensitivity analysis for multiple scenarios and models with implementation using sparse grid collocation. J. Hydrol. 2015, 528, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delle Monache, L.; Lundquist, J.K.; Kosovic, B.; Johannesson, G.; Dyer, K.M.; Aines, R.D.; Chow, F.K.; Belles, R.D.; Hanley, W.G.; Larsen, S.C.; et al. Bayesian Inference and Markov Chain Monte Carlo Sampling to Reconstruct a Contaminant Source on a Continental Scale. J. Appl. Meteorol. Clim. 2008, 47, 2600–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, W.; Xiong, J.; Chen, P. Sensitivity Analysis for Urban Drainage Modeling Using Mutual Information. Entropy 2014, 16, 5738–5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.-S.; Song, X.-M.; Xia, J.; Tong, C. An efficient integrated approach for global sensitivity analysis of hydrological model parameters. Environ. Model. Softw. 2013, 41, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhan, C.; Kong, F.; Xia, J. Advances in the study of uncertainty quantification of large-scale hydrological modeling system. J. Geogr. Sci. 2011, 21, 801–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotto, C.B.; Mannina, G.; Kleidorfer, M.; Vezzaro, L.; Henrichs, M.; McCarthy, D.T.; Freni, G.; Rauch, W.; Deletic, A. Comparison of different uncertainty techniques in urban stormwater quantity and quality modelling. Water Res. 2012, 46, 2545–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dotto, C.B.S.; Kleidorfer, M.; Deletic, A.; Rauch, W.; McCarthy, D.T. Impacts of measured data uncertainty on urban stormwater models. J. Hydrol. 2014, 508, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.A.; Manenti, S.; Reali, A.; Sangalli, G.; Tamellini, L.; Todeschini, S. Combining noisy well data and expert knowledge in a Bayesian calibration of a flow model under uncertainties: An application to solute transport in the Ticino basin. Int. J. Geomath. 2023, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muleta, M.K.; McMillan, J.; Amenu, G.G.; Burian, S.J. Bayesian Approach for Uncertainty Analysis of an Urban Storm Water Model and Its Application to a Heavily Urbanized Watershed. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2013, 18, 1360–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.M.; Che, H.; Smith, K.; Lei, M.S.Z.; Li, R.N. Performance evaluation for three pollution detection methods using data from a real contamination accident. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 161, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, A.; Rubin, D.B. Inference from Iterative Simulation Using Multiple Sequences. Stat. Sci. 1992, 7, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gironás, J.; Roesner, L.A.; Rossman, L.A.; Davis, J. A new applications manual for the Storm Water Management Model (SWMM). Environ. Model. Softw. 2010, 25, 813–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrazo-Uribeetxebarria, E.; Garmendia, M.; Berrondo, J.A.; Andrés-Doménech, I. Sensitivity analysis of permeable pavement hydrological modelling in the storm water management model. J. Hydrol. 2021, 600, 126525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.J.; Marshall, L.A. Bayesian methods in hydrologic modeling: A study of recent advancements in Markov chain Monte Carlo techniques. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, W00B05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, C.R. Identification and quantification of the hydrological impacts of imperviousness in urban catchments: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 1438–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Q.; Li, M.; Lu, Z. Assessing runoff control of low impact development in Hong Kong’s dense community with reliable SWMM setup and calibration. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Xu, T.; Liang, S.; Zhao, P.; Xu, C. Bayesian framework of parameter sensitivity, uncertainty, and identifiability analysis in complex water quality models. Environ. Modell. Softw. 2018, 104, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanim, A.H.; Smith-Lewis, C.; Downey, A.R.J.; Imran, J.; Goharian, E. Bayes_Opt-SWMM: A Gaussian process-based Bayesian optimization tool for real-time flood modeling with SWMM. Environ. Model. Softw. 2024, 179, 106122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleidorfer, M.; Deletic, A.; Fletcher, T.D.; Rauch, W. Impact of input data uncertainties on urban stormwater model parameters. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 1545–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, N.; Redfern, T.; Miller, J.; Kjeldsen, T.R. Understanding the impact of the built environment mosaic on rainfall-runoff behaviour. J. Hydrol. 2022, 604, 127147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, F.; Yu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Li, M.; Guan, Y. Comprehensive performance evaluation of LID practices for the sponge city construction: A case study in Guangxi, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 231, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.M.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zhan, C.S.; Xuan, Y.Q.; Ye, M.; Xu, C.G. Global sensitivity analysis in hydrological modeling: Review of concepts, methods, theoretical framework, and applications. J. Hydrol. 2015, 523, 739–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Hong, B.; Hall, M. Assessment of the SWMM model uncertainties within the generalized likelihood uncertainty estimation (GLUE) framework for a high-resolution urban sewershed. Hydrol. Process. 2014, 28, 3018–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossman, L.A.; Huber, W.C. Storm Water Management Model Reference Manual Volume I—Hydrology; U.S. EPA Office of Research and Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Vrugt, J.A.; ter Braak, C.J.F.; Diks, C.G.H.; Robinson, B.A.; Hyman, J.M.; Higdon, D. Accelerating Markov Chain Monte Carlo Simulation by Differential Evolution with Self-Adaptive Randomized Subspace Sampling. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2009, 10, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrugt, J.A. Markov chain Monte Carlo simulation using the DREAM software package: Theory, concepts, and MATLAB implementation. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 75, 273–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicens, G.J.; Rodriguez-Turbe, I.; Schaake, J.C. A Bayesian framework for the use of regional information in hydrology. Water Resour. Res. 1975, 11, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Jakeman, A.; Fang, G.; Chen, X. Uncertainty analysis of a semi-distributed hydrologic model based on a Gaussian Process emulator. Environ. Model. Softw. 2018, 101, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Imperv (%) | Width (m) | Slope (%) | N-Imperv | N-Perv | S-Imperv (mm) | S-Perv (mm) | Zero-Imperv (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “True” value | 50 | 500 | 4 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 2 | 5 | 0 |

| Value range | 30–80 | 200–800 | 2–6 | 0.005–0.03 | 0.05–0.2 | 1–3 | 2.5–7.5 | 0–25 |

| Rainfall Event | Return Period (a) | Total Rainfall Depth (mm) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| rain1 (R1) | - | 2.91 | Low-intensity rainfalls used for urban runoff pollution control purposes |

| rain2 (R2) | 0.25 | 8.43 | |

| rain3 (R3) | 0.3 | 12.94 | |

| rain4 (R4) | 0.5 | 25.56 | |

| rain5 (R5) | 1 | 42.70 | Medium-intensity rainfalls used for urban drainage pipe system design purposes |

| rain6 (R6) | 2 | 59.84 | |

| rain7 (R7) | 5 | 82.49 | |

| rain8 (R8) | 10 | 99.62 | High-intensity rainfalls used for urban flooding control purposes |

| rain9 (R9) | 20 | 116.76 |

| Watershed Type | Two Types of Terrain Features | Three Development Levels | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flat (Slope = 0.4%) | Steep (Slope = 4%) | Undeveloped (20% Impervious) | Medium-Developed (50% Impervious) | Fully Developed (80% Impervious) | |

| Type I | X | X | |||

| Type II | X | X | |||

| Type III | X | X | |||

| Type IV | X | X | |||

| Type V | X | X | |||

| Type VI | X | X | |||

| Imperv (%) | Width (m) | Slope (%) | N-Imperv | N-Perv | S-Imperv (mm) | S-Perv (mm) | Zero-Imperv (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True value | 50 | 500 | 4 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 2 | 5 | 0 |

| Prior distribution range | 30–80 | 200–800 | 2–6 | 0.005–0.03 | 0.05–0.2 | 1–3 | 2.5–7.5 | 0–25 |

| Mean value | 50.095 | 643.212 | 4.393 | 0.014 | 0.118 | 1.956 | 5.456 | 4.316 |

| Standard deviation | 0.243 | 168.647 | 0.887 | 0.005 | 0.032 | 0.087 | 0.610 | 4.783 |

| Coefficient of variation | 0.005 | 0.262 | 0.202 | 0.332 | 0.274 | 0.045 | 0.112 | 1.108 |

| Standard Deviation of Parameter Posterior Distribution | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Peak | Double-Peak | Triple-Peak | |

| Imperv (%) | 0.243 | 0.203 | 0.310 |

| Width (m) | 168.647 | 110.789 | 157.441 |

| Slope (%) | 0.887 | 1.014 | 1.022 |

| N-imperv | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| N-perv | 0.032 | 0.021 | 0.042 |

| S-imperv (mm) | 0.087 | 0.211 | 0.231 |

| S-perv (mm) | 0.610 | 0.441 | 0.477 |

| Zero-imperv (%) | 4.783 | 4.447 | 10.047 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shao, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Du, J.; Yost, S. Bridging Uncertainty in SWMM Model Calibration: A Bayesian Analysis of Optimal Rainfall Selection. Water 2025, 17, 3435. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233435

Shao Z, Wang J, Zhang X, Du J, Yost S. Bridging Uncertainty in SWMM Model Calibration: A Bayesian Analysis of Optimal Rainfall Selection. Water. 2025; 17(23):3435. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233435

Chicago/Turabian StyleShao, Zhiyu, Jinsong Wang, Xiaoyuan Zhang, Jiale Du, and Scott Yost. 2025. "Bridging Uncertainty in SWMM Model Calibration: A Bayesian Analysis of Optimal Rainfall Selection" Water 17, no. 23: 3435. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233435

APA StyleShao, Z., Wang, J., Zhang, X., Du, J., & Yost, S. (2025). Bridging Uncertainty in SWMM Model Calibration: A Bayesian Analysis of Optimal Rainfall Selection. Water, 17(23), 3435. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233435