Impact of Seafloor Morphology on Regional Sea Level Rise in the Japan Trench Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area

3. Materials

3.1. Satellite Altimetry Dataset

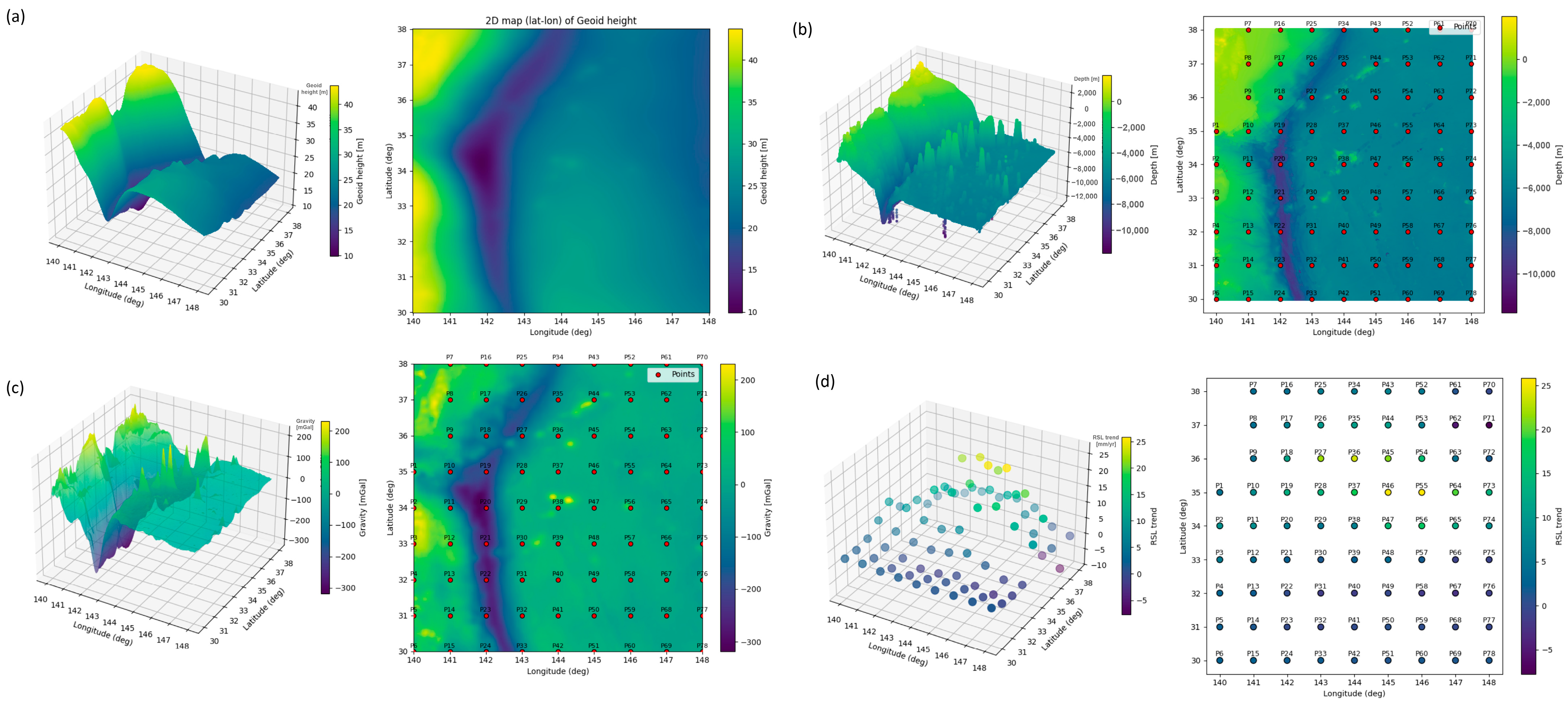

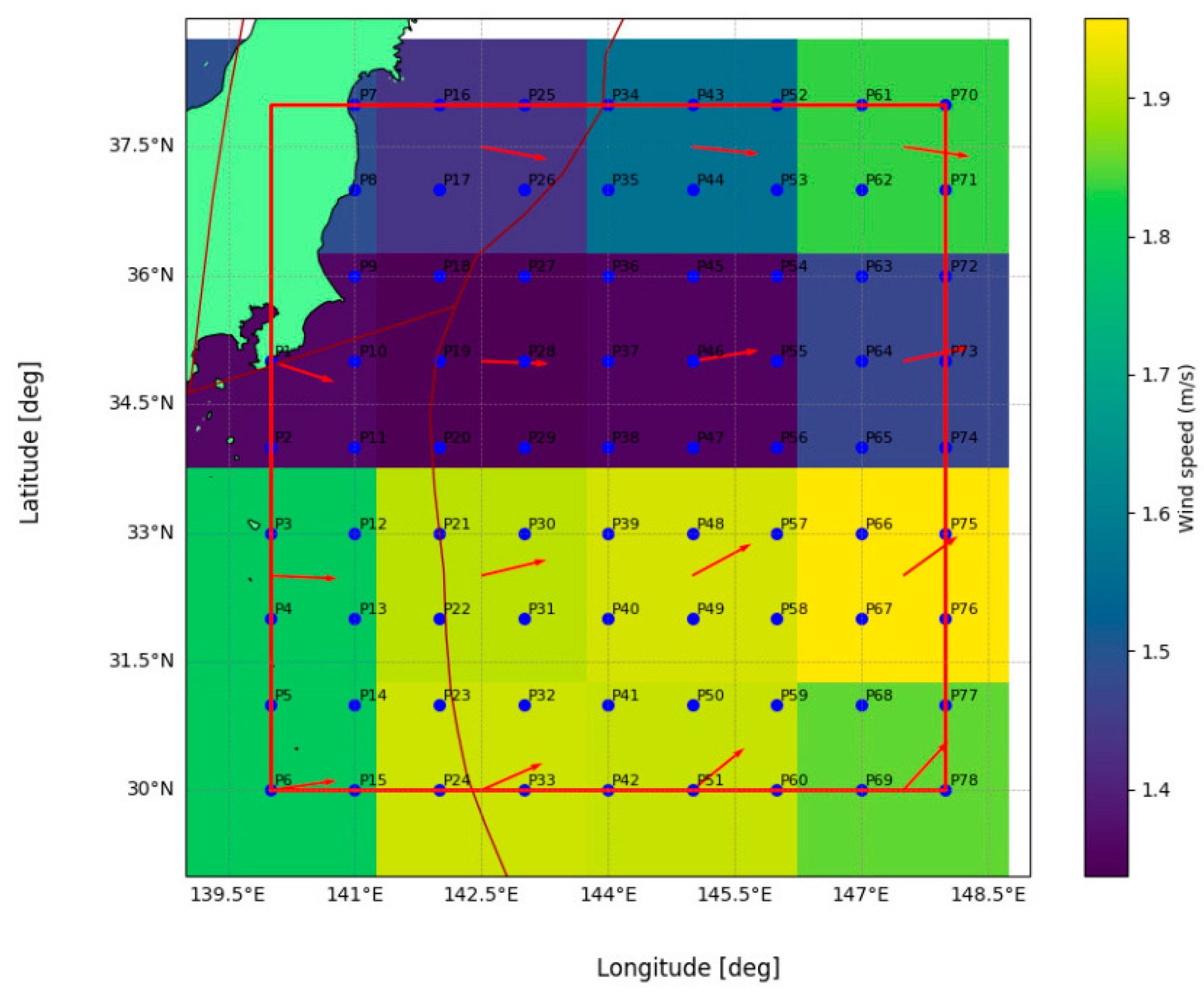

3.2. Bathymetry Dataset

3.3. Gravity Anomalies Model and Geoid Model

3.4. Mean Dynamic Topography Model

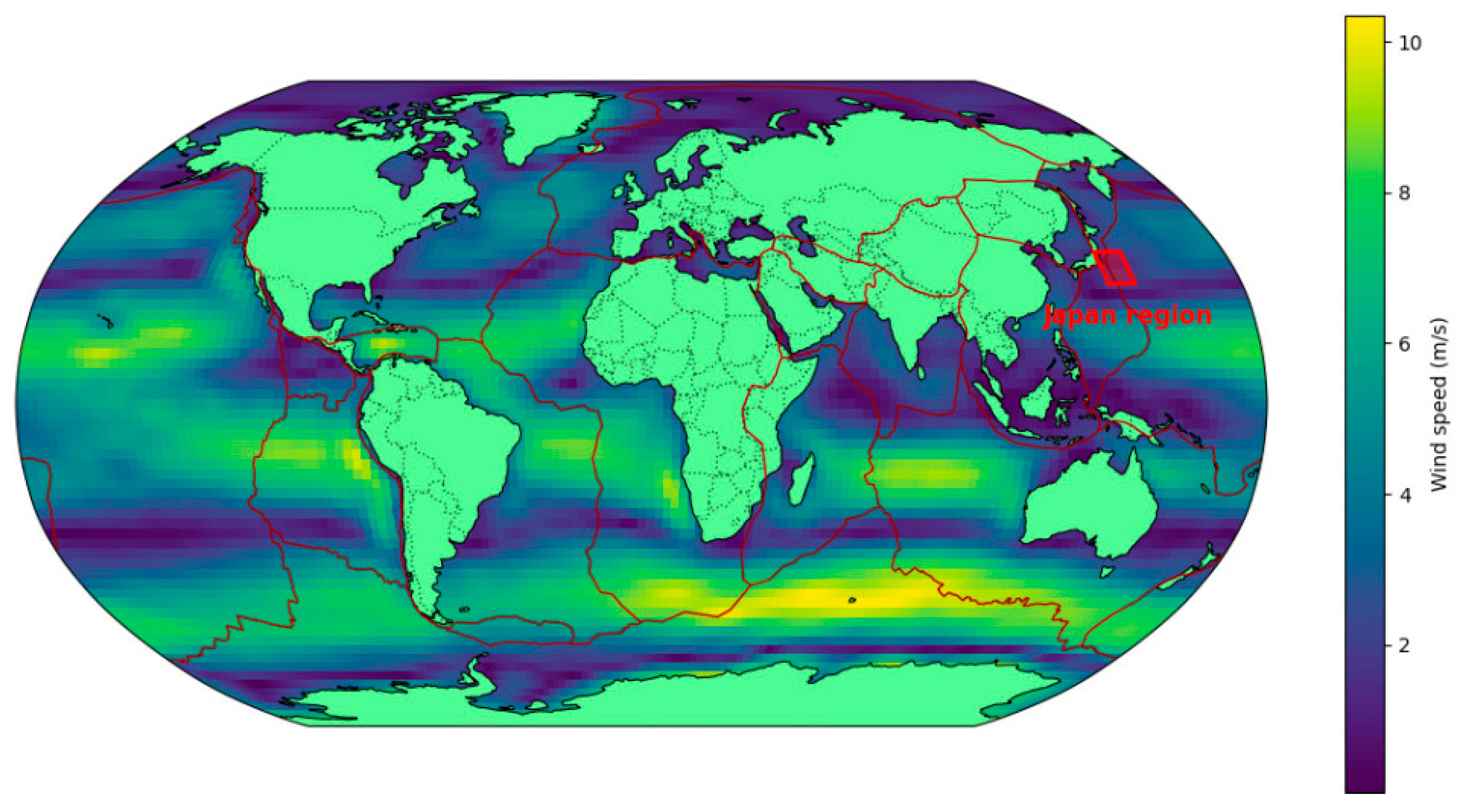

3.5. Wind Speed and Direction

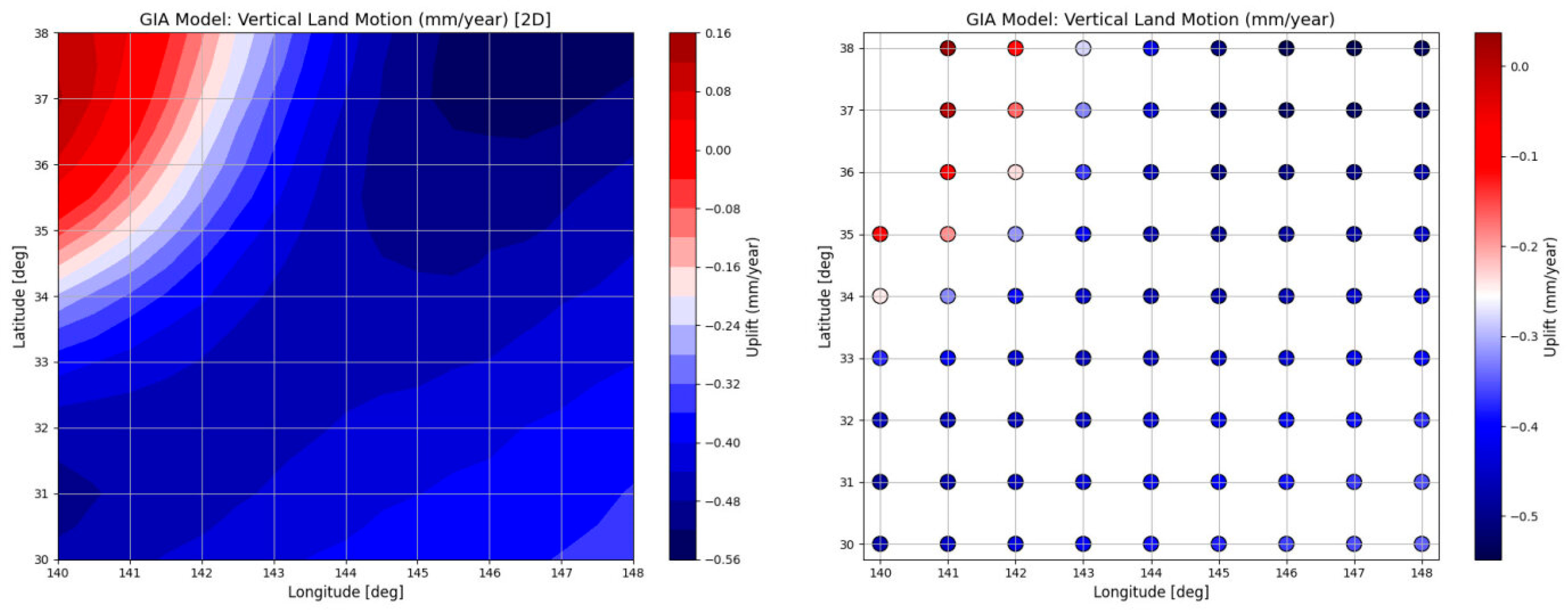

3.6. Glacial Isostatic Adjustment (GIA) Model

4. Methodology

5. Results

5.1. Long-Term, Regional SLR Variability Regarding Seafloor Morphology

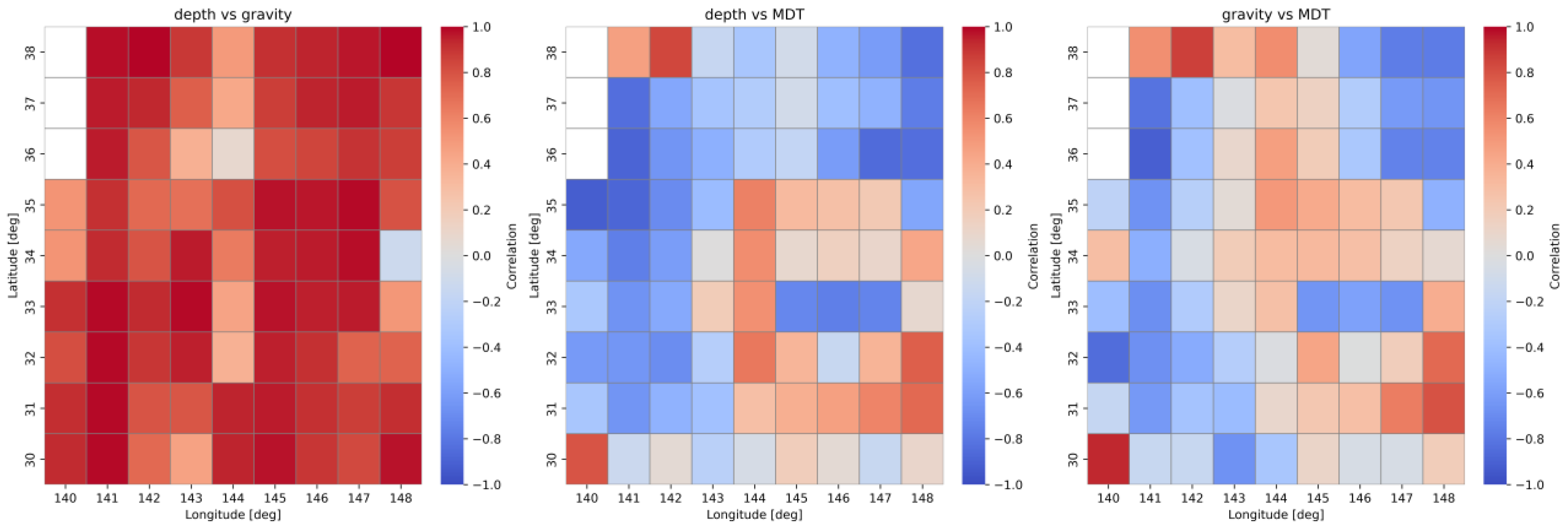

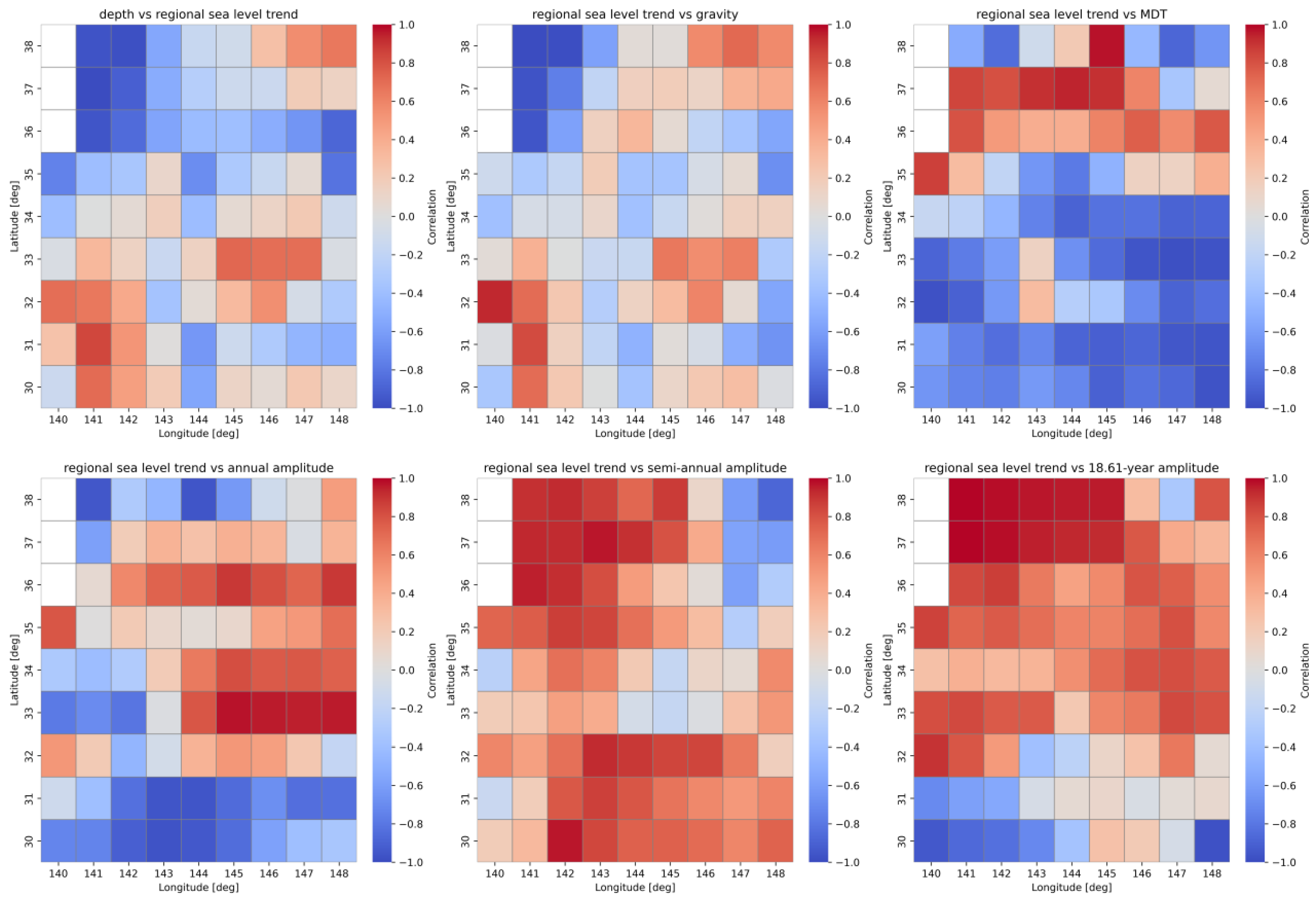

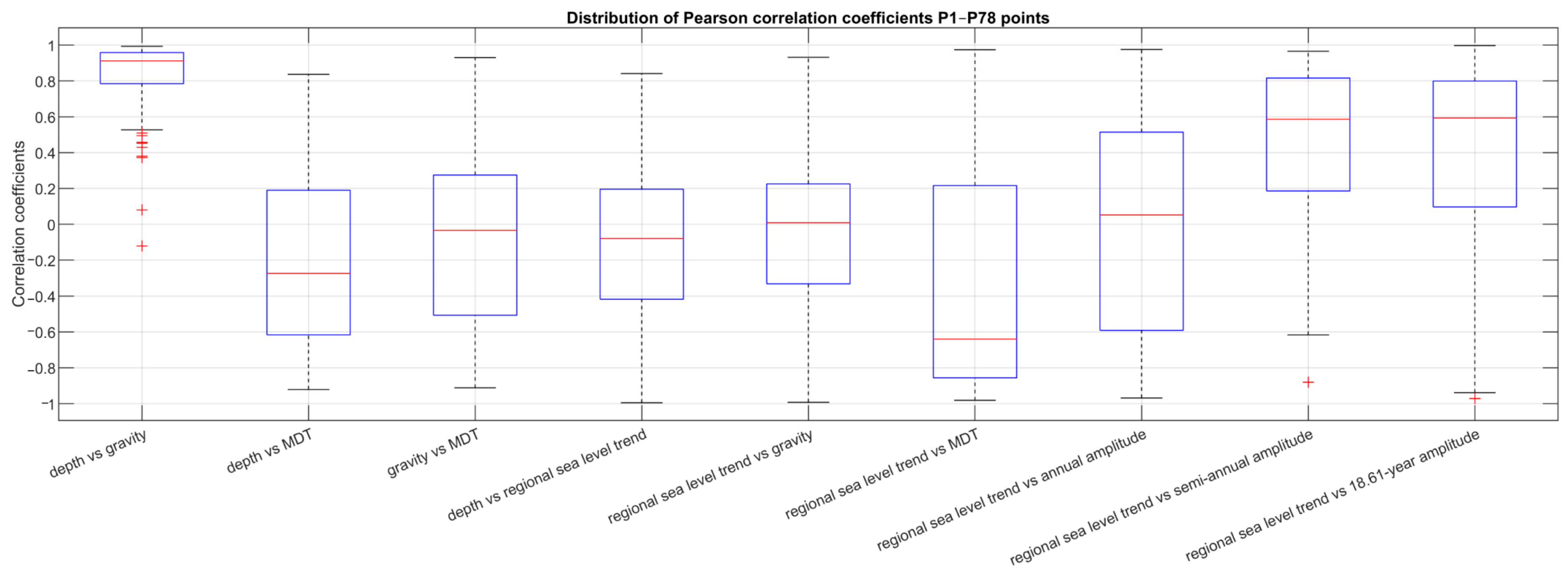

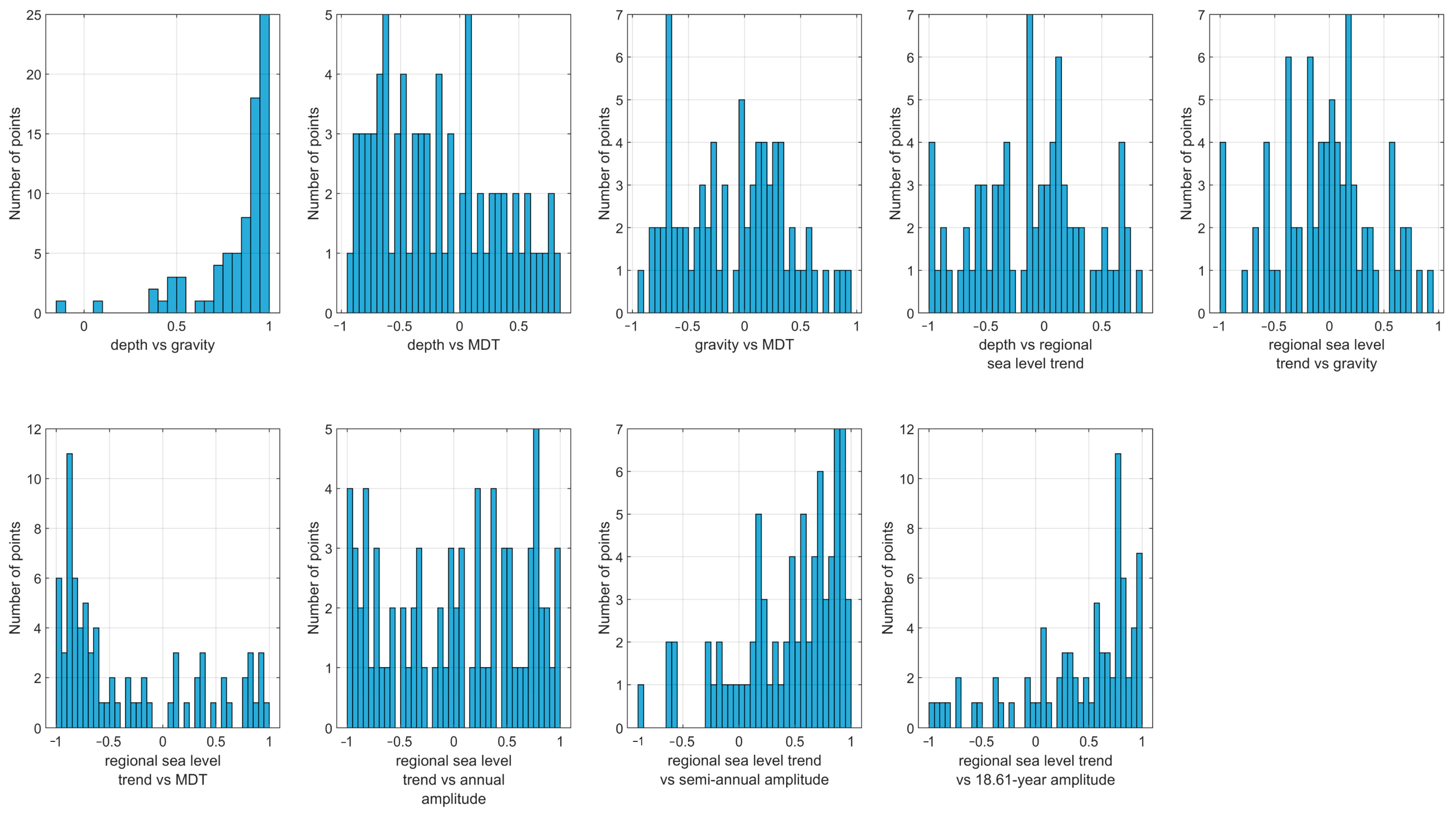

5.2. Analysis of Correlations Between Geophysical Parameters and SLR Trend

5.3. The Importance of Seafloor Topography, Gravity Anomalies, Geoid Heights, and GIA Corrections in SLR Trend Estimation

5.4. The Impact of Wind Speed and Direction on SLR Variability

6. Validation and SLR Simulation

6.1. Validation of SLR Trend Estimation Methods (Harmonic Method, CWT, and Kalman Filter)

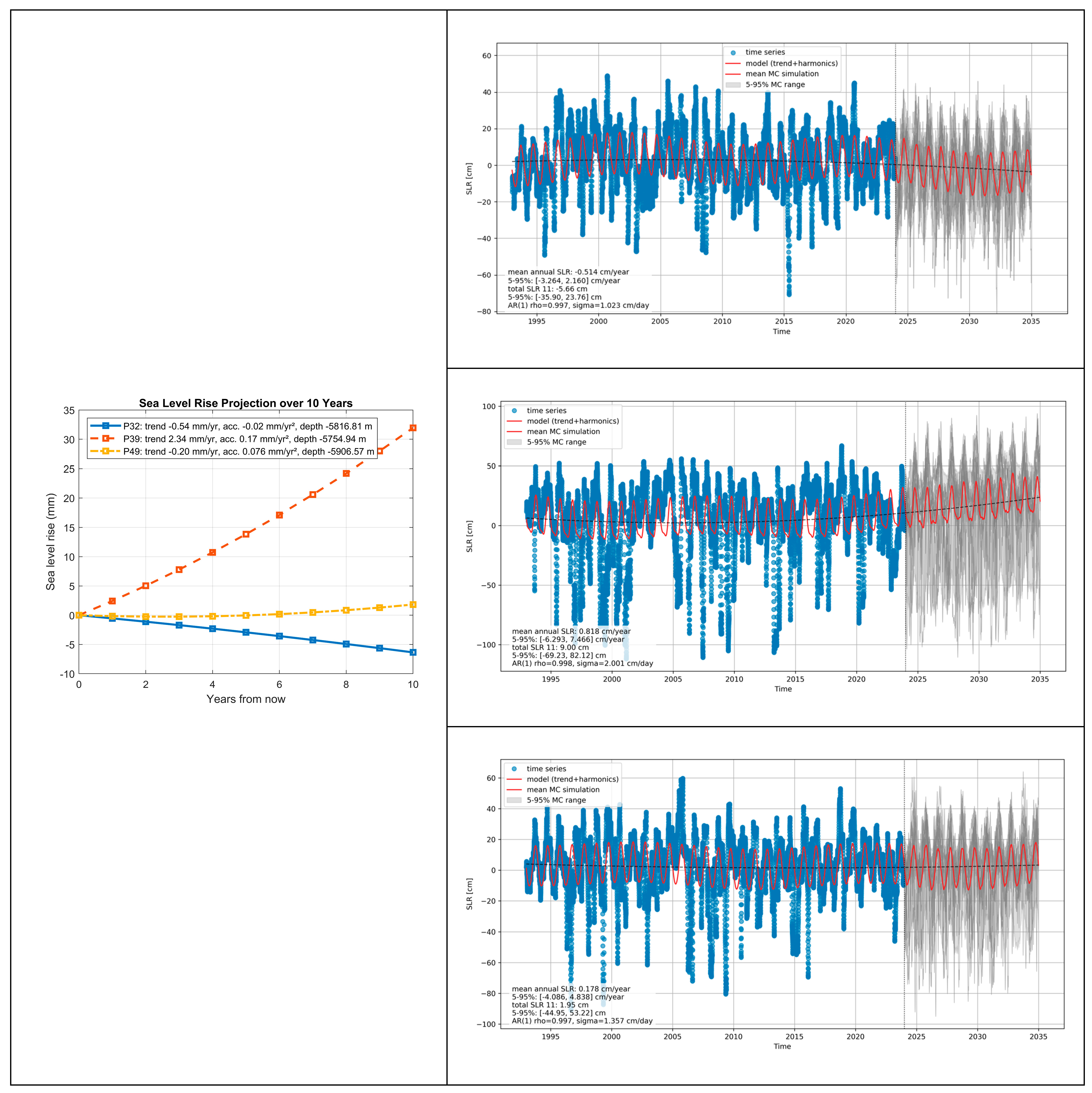

6.2. The Impact of Seafloor Morphology on SLR Acceleration in Light of Monte Carlo Simulations

7. Discussion

7.1. The Impact of Seafloor Morphology on Regional Sea Level Variability

7.2. Correlation Analyses and the Effects of the Lunar Nodal Cycle

7.3. Validation of Trend Estimation Methods, GIA Correction, and Identification of SLR Accelerations

7.4. Practical Significance of the Results—The Impact of Seafloor Topography on Sea Level Rise

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CMEMS | Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service |

| GEBCO | General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans |

| SIO | Scripps Institution of Oceanography |

| NOAA NCEI | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Centers for Environmental Information |

| SLA | Sea Level Anomaly |

| MDT | Mean Dynamic Ocean Topography |

| GIA | Glacial Isostatic Adjustment |

| SLR | Sea Level Rise |

| CWT | Continuous Wavelet Transform |

| KF | Kalman Filter |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| VLM | Vertical Land Movements |

References

- Sriver, R.L.; Lempert, R.J.; Wikman-Svahn, P.; Keller, K. Characterizing uncertain sea-level rise projections to support investment decisions. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, B.P.; Khan, N.S.; Cahill, N.; Lee, J.S.H.; Shaw, T.A.; Garner, A.J.; Kemp, A.C.; Engelhart, S.E.; Rahmstorf, S. Estimating global mean sea-level rise and its uncertainties by 2100 and 2300 from an expert survey. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2020, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Jenkins, K.; Goodwin, P.; Lincke, D.; Vafeidis, A.T.; Tol, R.S.J.; Jenkins, R.; Warren, R.; Nicholls, R.J.; Jevrejeva, S.; et al. Global costs of protecting against sea-level rise at 1.5 to 4.0 °C. Clim. Change 2021, 167, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelsmann, J.; Nicholls, R.; Lincke, D.; Marcos, M.; Sánchez, L.; Dettmering, D.; Hinkel, J.; Horton, B.; Seitz, F. Coastal populations experience sea level rise at least twice as large as the global average. Res. Sq. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vousdoukas, M.I.; Mentaschi, L.; Voukouvalas, E.; Bianchi, A.; Dottori, F.; Feyen, L. Climatic and socioeconomic controls of future coastal flood risk in Europe. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlington, B.D.; Gardner, A.S.; Ivins, E.; Lenaerts, J.T.M.; Reager, J.T.; Trossman, D.S.; Zaron, E.D.; Adhikari, S.; Arendt, A.; Aschwanden, A.; et al. Understanding of Contemporary Regional Sea-Level Change and the Implications for the Future. Rev. Geophys. 2020, 58, e2019RG000672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwigsen, C.B.; Andersen, O.B.; Marzeion, B.; Malles, J.-H.; Müller Schmied, H.; Döll, P.; Watson, C.; King, M.A. Global and regional ocean mass budget closure since 2003. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, D.; Huang, R.; Xu, T.; Yan, H. Inferring Global Ocean Mass Increase from Tide Gauges Network with Climate Models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2023GL108056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederikse, T.; Riva, R.E.M.; King, M.A. Ocean Bottom Deformation Due To Present-Day Mass Redistribution and Its Impact on Sea Level Observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 12306–12314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Atienza, V.M.; Tago, J.; Domínguez, L.A.; Kostoglodov, V.; Ito, Y.; Ovando-Shelley, E.; Rodríguez-Nikl, T.; González, R.; Franco, S.; Solano-Rojas, D.; et al. Seafloor geodesy unveils seismogenesis of large subduction earthquakes in Mexico. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadu8259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldaña, B.; Cisternas, M.; Carvajal, M.; Melnick, D.; Cortés-Aranda, J.; Francois, J.P.; Carreño, A.; Guerra, M. Paleoseismological evidence of a century of coastal deformation in central Chile: Lasting emergence and ongoing submergence. Quat. Sci. Adv. 2025, 19, 100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broerse, T.; Riva, R.; Vermeersen, B. Ocean contribution to seismic gravity changes: The sea level equation for seismic perturbations revisited. Geophys. J. Int. 2014, 199, 1094–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Yu, Y.; Chao, B.F. Gravity and geoid changes by the 2004 and 2012 Sumatra earthquakes from satellite gravimetry and ocean altimetry. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 2019, 30, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Sun, H.; Xu, J.; Chen, X.; Cui, X. Co-seismic change in ocean bottom topography: Implication to absolute global mean sea level change. Geod. Geodyn. 2019, 10, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grezio, A.; Anzidei, M.; Baglione, E.; Brizuela, B.; Di Manna, P.; Selva, J.; Taroni, M.; Tonini, R.; Vecchio, A. Including sea-level rise and vertical land movements in probabilistic tsunami hazard assessment for the Mediterranean Sea. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, R.D.; Luthcke, S.B.; Van Dam, T. Monthly Crustal Loading Corrections for Satellite Altimetry. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2013, 30, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, P.C.; Fischer, A.C.; Lewis-Brown, E.; Meredith, M.P.; Sparrow, M.; Andersson, A.J.; Antia, A.; Bates, N.R.; Bathmann, U.; Beaugrand, G.; et al. Chapter 1 Impacts of the Oceans on Climate Change. In Advances in Marine Biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 56, pp. 1–150. ISBN 978-0-12-374960-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Myhill, R.; Guo, H. Slab morphology and deformation beneath Izu-Bonin. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, Y.; Nakano, H.; Urakawa, L.S.; Toyoda, T.; Aoki, K.; Usui, N. Northward shift of the Kuroshio Extension during 1993–2021. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Ma, C.; Jing, Z.; Zhang, Z. On the Vertical Structure of Mesoscale Eddies in the Kuroshio-Oyashio Extension. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2023GL105642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Chang, P.; Shan, X.; Wang, S.; Wu, L.; Kurian, J. Mesoscale SST Dynamics in the Kuroshio–Oyashio Extension Region. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2019, 49, 1339–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Tony Song, Y. Sea level and heat content changes in the western North Pacific. JGR Ocean. 2013, 118, 2014–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, R.; Ashi, J. Sediment Transport Modeling Based on Geological Data for Holocene Coastal Evolution: Wave Source Estimation of Sandy Layers on the Coast of Hidaka, Hokkaido, Japan. JGR Earth Surf. 2022, 127, e2022JF006721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodaira, S.; Takahashi, N.; Nakanishi, A.; Miura, S.; Kaneda, Y. Subducted Seamount Imaged in the Rupture Zone of the 1946 Nankaido Earthquake. Science 2000, 289, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, G.; Kitamura, Y.; Yamaguchi, A.; Kameda, J.; Hashimoto, Y.; Hamahashi, M. Origin of the early Cenozoic belt boundary thrust and Izanagi–Pacific ridge subduction in the western Pacific margin. Isl. Arc 2019, 28, e12320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguri, K.; Kawamura, K.; Sakaguchi, A.; Toyofuku, T.; Kasaya, T.; Murayama, M.; Fujikura, K.; Glud, R.N.; Kitazato, H. Hadal disturbance in the Japan Trench induced by the 2011 Tohoku–Oki Earthquake. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, T.; Goto, H.; Watanabe, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Nishizawa, A.; Izumi, N.; Horiuchi, D.; Kido, Y. Active Faults along Japan Trench and Source Faults of Large Earthquakes. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Engineering Lessons Learned from the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, Tokyo, Japan, 3–4 March 2012; pp. 254–262. [Google Scholar]

- Iinuma, T.; Hino, R.; Kido, M.; Inazu, D.; Osada, Y.; Ito, Y.; Ohzono, M.; Tsushima, H.; Suzuki, S.; Fujimoto, H.; et al. Coseismic slip distribution of the 2011 off the Pacific Coast of Tohoku Earthquake (M9.0) refined by means of seafloor geodetic data. J. Geophys. Res. 2012, 117, 2012JB009186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujie, G.; Kodaira, S.; Sato, T.; Takahashi, T. Along-trench variations in the seismic structure of the incoming Pacific plate at the outer rise of the northern Japan Trench. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemenkova, P. Variations in the bathymetry and bottom morphology of the Izu-Bonin Trench modelled by GMT. Bull. Geography. Phys. Geogr. Ser. 2020, 18, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, W.; Taira, A.; Tokuyama, H. A trench fan in the Izu-Ogasawara Trench on the Boso Trench triple junction, Japan. Mar. Geol. 1988, 82, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Ye, J.; Pérez Gómez, B.; Gallardo, A.; Manzano, F.; De Alfonso, M.; Bradshaw, E.; Hibbert, A. Delayed-mode reprocessing of in situ sea level data for the Copernicus Marine Service. Ocean Sci. 2023, 19, 1743–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciliberti, S.A.; Grégoire, M.; Staneva, J.; Palazov, A.; Coppini, G.; Lecci, R.; Peneva, E.; Matreata, M.; Marinova, V.; Masina, S.; et al. Monitoring and Forecasting the Ocean State and Biogeochemical Processes in the Black Sea: Recent Developments in the Copernicus Marine Service. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union-Copernicus Marine Service. Global Ocean Gridded L4 Sea Surface Heights and Derived Variables Reprocessed (1993-Ongoing); European Union-Copernicus Marine Service: Toulouse, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballarotta, M.; Dagneaux, Q.; Delepoulle, A.; Dibarboure, G.; Dupuy, S.; Faugère, Y.; Jenn-Alet, M.; Kocha, C.; Pujol, I.; Taburet, G. DUACS DT-2024: 30 years of reprocessed sea level altimetry products. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly 2025, Vienna, Austria, 27 April–2 May 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLain, K. Processed Acoustic Backscatter and Swath Bathymetry Data Acquired During R/V Roger Revelle Expedition ZHNG08RR (2005). Mar. Geosci. Data Syst. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E. Processed Acoustic Backscatter and Swath Bathymetry Data Acquired During R/V Roger Revelle Expedition ZHNG07RR (2005). Mar. Geosci. Data Syst. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherall, P.; Ferreras, S.C.; Cardigos, S.D.; Cornish, N.; Davidson, S.R.; Dorschel, B.; Drennon, H.; Ferrini, V.; Harper, H.A.; Isler, T.; et al. GEBCO Bathymetric Compilation Group 2024. The GEBCO_2024 Grid—A Continuous Terrain Model of the Global Oceans and Land; NERC EDS British Oceanographic Data Centre NOC: Liverpool, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, H.; Sandwell, D.T. Global Predicted Bathymetry Using Neural Networks. Earth Space Sci. 2024, 11, e2023EA003199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozer, B.; Sandwell, D.T.; Smith, W.H.F.; Olson, C.; Beale, J.R.; Wessel, P. Global Bathymetry and Topography at 15 Arc Sec: SRTM15+. Earth Space Sci. 2019, 6, 1847–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Guo, J.; Chang, X.; Wang, Z.; Jia, Y.; Liu, X.; Bondur, V.; Sun, H. High-precision 1′ × 1′ bathymetric model of Philippine Sea inversed from marine gravity anomalies. Geosci. Model Dev. 2024, 17, 2039–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.-S.; Pham, V.-T.; Van Nguyen, L.; Andersen, O.B.; Forsberg, R.; Tien Bui, D. Marine gravity anomaly mapping for the Gulf of Tonkin area (Vietnam) using Cryosat-2 and Saral/AltiKa satellite altimetry data. Adv. Space Res. 2020, 66, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.H.F.; Sandwell, D.T. Bathymetric prediction from dense satellite altimetry and sparse shipboard bathymetry. J. Geophys. Res. 1994, 99, 21803–21824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, K.; Kuroishi, Y. Refinement of a gravimetric geoid model for Japan using GOCE and an updated regional gravity field model. Earth Planets Space 2020, 72, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, J.; Shi, H.; He, X. Mean Dynamic Topography Modeling Based on Optimal Interpolation from Satellite Gravimetry and Altimetry Data. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, P.; Andersen, O.; Maximenko, N. A new ocean mean dynamic topography model, derived from a combination of gravity, altimetry and drifter velocity data. Adv. Space Res. 2021, 68, 1090–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophaug, V.; Breili, K.; Gerlach, C. A comparative assessment of coastal mean dynamic topography in N orway by geodetic and ocean approaches. JGR Ocean. 2015, 120, 7807–7826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäggi, A.; Weigelt, M.; Flechtner, F.; Güntner, A.; Mayer-Gürr, T.; Martinis, S.; Bruinsma, S.; Flury, J.; Bourgogne, S.; Steffen, H.; et al. European Gravity Service for Improved Emergency Management (EGSIEM)—From concept to implementation. Geophys. J. Int. 2019, 218, 1572–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, W.R.; Argus, D.F.; Drummond, R. Space geodesy constrains ice age terminal deglaciation: The global ICE-6G_C (VM5a) model. JGR Solid Earth 2015, 120, 450–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argus, D.F.; Peltier, W.R.; Drummond, R.; Moore, A.W. The Antarctica component of postglacial rebound model ICE-6G_C (VM5a) based on GPS positioning, exposure age dating of ice thicknesses, and relative sea level histories. Geophys. J. Int. 2014, 198, 537–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowan, E.J.; Tregoning, P.; Purcell, A.; Montillet, J.-P.; McClusky, S. A model of the western Laurentide Ice Sheet, using observations of glacial isostatic adjustment. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2016, 139, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse, P.L.; Bentley, M.J.; Le Brocq, A.M. A deglacial model for Antarctica: Geological constraints and glaciological modelling as a basis for a new model of Antarctic glacial isostatic adjustment. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2012, 32, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idzikowska, M.; Pajak, K.; Kowalczyk, K. Long-Term Sea Surface Variability Regarding Seafloor Topography. Sensors 2025, 25, 6391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulte, J.A. Wavelet analysis for non-stationary, nonlinear time series. Nonlin. Process. Geophys. 2016, 23, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkhou, A.; Jbari, A.; Belarbi, L. A continuous wavelet based technique for the analysis of electromyography signals. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Electrical and Information Technologies (ICEIT), Rabat, Morocco, 15–18 November 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, C.; Harrington, P.d.B. Different Discrete Wavelet Transforms Applied to Denoising Analytical Data. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1998, 38, 1161–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, P.S. Introduction to redundancy rules: The continuous wavelet transform comes of age. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 2018, 376, 20170258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.N.; Cane, M.A. A Kalman Filter Analysis of Sea Level Height in the Tropical Pacific. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1989, 19, 773–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosetti, R. A Kalman-filter estimate of the tidal harmonic constants. II Nuovo C. C 1983, 6, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsiddieg, A.M.A. Quantifying the Impact of Sea Level on Coastal Cities using Bayesian optimized Monte Carlo Simulation model. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci. 2024, 18, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clare, M.C.A.; Leijnse, T.W.B.; McCall, R.T.; Diermanse, F.L.M.; Cotter, C.J.; Piggott, M.D. Multilevel multifidelity Monte Carlo methods for assessing uncertainty in coastal flooding. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 22, 2491–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.; Lu, B. Autoregressive Model for Time Series as a Deterministic Dynamic System. Predict. Anal. Futur. 2017, 7, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G. The 95 per cent confidence interval for the mean sea-level change rate derived from tide gauge data. Geophys. J. Int. 2023, 235, 1420–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idzikowska, M.; Pająk, K.; Kowalczyk, K. Possibility and quality assessment in seafloor modeling relative to the sea surface using hybrid data. Trans. GIS 2024, 28, 1175–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlington, B.D.; Bellas-Manley, A.; Willis, J.K.; Fournier, S.; Vinogradova, N.; Nerem, R.S.; Piecuch, C.G.; Thompson, P.R.; Kopp, R. The rate of global sea level rise doubled during the past three decades. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renkl, C.; Oliver, E.C.J.; Thompson, K.R. The alongshore tilt of mean dynamic topography and its implications for model validation and ocean monitoring. Ocean Sci. 2025, 21, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rio, M.-H.; Hernandez, F. A mean dynamic topography computed over the world ocean from altimetry, in situ measurements, and a geoid model. J. Geophys. Res. 2004, 109, 2003JC002226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Traon, P.-Y.; Antoine, D.; Bentamy, A.; Bonekamp, H.; Breivik, L.A.; Chapron, B.; Corlett, G.; Dibarboure, G.; DiGiacomo, P.; Donlon, C.; et al. Use of satellite observations for operational oceanography: Recent achievements and future prospects. J. Oper. Oceanogr. 2015, 8, s12–s27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Traon, P.Y. From satellite altimetry to Argo and operational oceanography: Three revolutions in oceanography. Ocean Sci. 2013, 9, 901–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodworth, P.L. A Note on the Nodal Tide in Sea Level Records. J. Coast. Res. 2012, 280, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlington, B.D.; Frederikse, T.; Nerem, R.S.; Fasullo, J.T.; Adhikari, S. Investigating the Acceleration of Regional Sea Level Rise During the Satellite Altimeter Era. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2019GL086528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verolino, A.; Wee, S.F.; Jenkins, S.F.; Costa, F.; Switzer, A.D. SEATANI: Hazards from seamounts in Southeast Asia, Taiwan, and Andaman and Nicobar Islands (eastern India). Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 24, 1203–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, T.; Dos Santos Ferreira, C.; Bachmann, A.K.; Strasser, M.; Wefer, G.; Sun, T.; Kanamatsu, T.; Kodaira, S. Seafloor Displacement After the 2011 Tohoku-oki Earthquake in the Northern Japan Trench Examined by Repeated Bathymetric Surveys. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 11833–11839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazenave, A.; Moreira, L. Contemporary sea-level changes from global to local scales: A review. Proc. R. Soc. A 2022, 478, 20220049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A. Long-term global sea-level change due to dynamic topography since 410 Ma. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2023, 191, 103944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhu, C.; Liu, X.; Hwang, C.; Lebedev, S.; Chang, X.; Soloviev, A.; Sun, H. The SDUST2022GRA global marine gravity anomalies recovered from radar and laser altimeter data: Contribution of ICESat-2 laser altimetry. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 4119–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Hill, E.M.; Meltzner, A.J.; Switzer, A.D. Tide Gauge Records Show That the 18.61-Year Nodal Tidal Cycle Can Change High Water Levels by up to 30 cm. JGR Ocean. 2019, 124, 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, I.D.; Eliot, M.; Pattiaratchi, C. Global influences of the 18.61 year nodal cycle and 8.85 year cycle of lunar perigee on high tidal levels. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2011, 116, C06025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Shu, Y.; Wang, W.; He, G.; Liang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Yu, L.; Wang, J.; Deng, X.; Yang, Y.; et al. Observations of Intermittent Seamount-Trapped Waves and Topographic Rossby Waves around the Slope of a Low-Latitude Deep Seamount. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2024, 54, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelegger, M.; Kotzian, D.P.; Ray, R.D.; Green, J.A.M.; Stolzenberger, S. Interannual Changes in Tidal Conversion Modulate M2 Amplitudes in the Gulf of Maine. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL101671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Devlin, A.T.; Xu, T.; Lv, X.; Wei, Z. Anomalous 18.61-Year Nodal Cycles in the Gulf of Tonkin Revealed by Tide Gauges and Satellite Altimeter Records. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelsmann, J.; Marcos, M.; Passaro, M.; Sanchez, L.; Dettmering, D.; Dangendorf, S.; Seitz, F. Regional variations in relative sea-level changes influenced by nonlinear vertical land motion. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangendorf, S.; Sun, Q.; Wahl, T.; Thompson, P.; Mitrovica, J.X.; Hamlington, B. Probabilistic reconstruction of sea-level changes and their causes since 1900. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 3471–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkey, S.G.; Johnson, G.C. Warming of Global Abyssal and Deep Southern Ocean Waters between the 1990s and 2000s: Contributions to Global Heat and Sea Level Rise Budgets *. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 6336–6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangendorf, S.; Hay, C.; Calafat, F.M.; Marcos, M.; Piecuch, C.G.; Berk, K.; Jensen, J. Persistent acceleration in global sea-level rise since the 1960s. Nat. Clim. Change 2019, 9, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazloff, M.R.; Gille, S.T.; Cornuelle, B. Improving the geoid: Combining altimetry and mean dynamic topography in the California coastal ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 8944–8952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachler, B.; Seiffert, R.; Rasquin, C.; Kösters, F. Tidal response to sea level rise and bathymetric changes in the German Wadden Sea. Ocean Dyn. 2020, 70, 1033–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passeri, D.L.; Hagen, S.C.; Medeiros, S.C.; Bilskie, M.V.; Alizad, K.; Wang, D. The dynamic effects of sea level rise on low-gradient coastal landscapes: A review. Earth’s Future 2015, 3, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trend [mm/yr] | Mean | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Variance | Std. Dev. | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harmonic analysis | 5.65 | 3.88 | −7.75 | 25.84 | 51.15 | 7.15 | 1.11 | 0.82 |

| Kalman filter (OLS) | 6.27 | 3.95 | −7.06 | 27.70 | 55.35 | 7.44 | 1.15 | 0.79 |

| Kalman filter (robust) | 5.92 | 2.84 | −6.27 | 29.95 | 62.05 | 7.88 | 1.44 | 1.52 |

| Wavelet transform | 6.21 | 3.83 | −7.56 | 28.44 | 58.53 | 7.65 | 1.22 | 1.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Idzikowska, M.; Pajak, K.; Kowalczyk, K. Impact of Seafloor Morphology on Regional Sea Level Rise in the Japan Trench Region. Water 2025, 17, 3433. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233433

Idzikowska M, Pajak K, Kowalczyk K. Impact of Seafloor Morphology on Regional Sea Level Rise in the Japan Trench Region. Water. 2025; 17(23):3433. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233433

Chicago/Turabian StyleIdzikowska, Magdalena, Katarzyna Pajak, and Kamil Kowalczyk. 2025. "Impact of Seafloor Morphology on Regional Sea Level Rise in the Japan Trench Region" Water 17, no. 23: 3433. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233433

APA StyleIdzikowska, M., Pajak, K., & Kowalczyk, K. (2025). Impact of Seafloor Morphology on Regional Sea Level Rise in the Japan Trench Region. Water, 17(23), 3433. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233433