Comparative Distribution of Microplastics in Different Inland Aquatic Ecosystems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

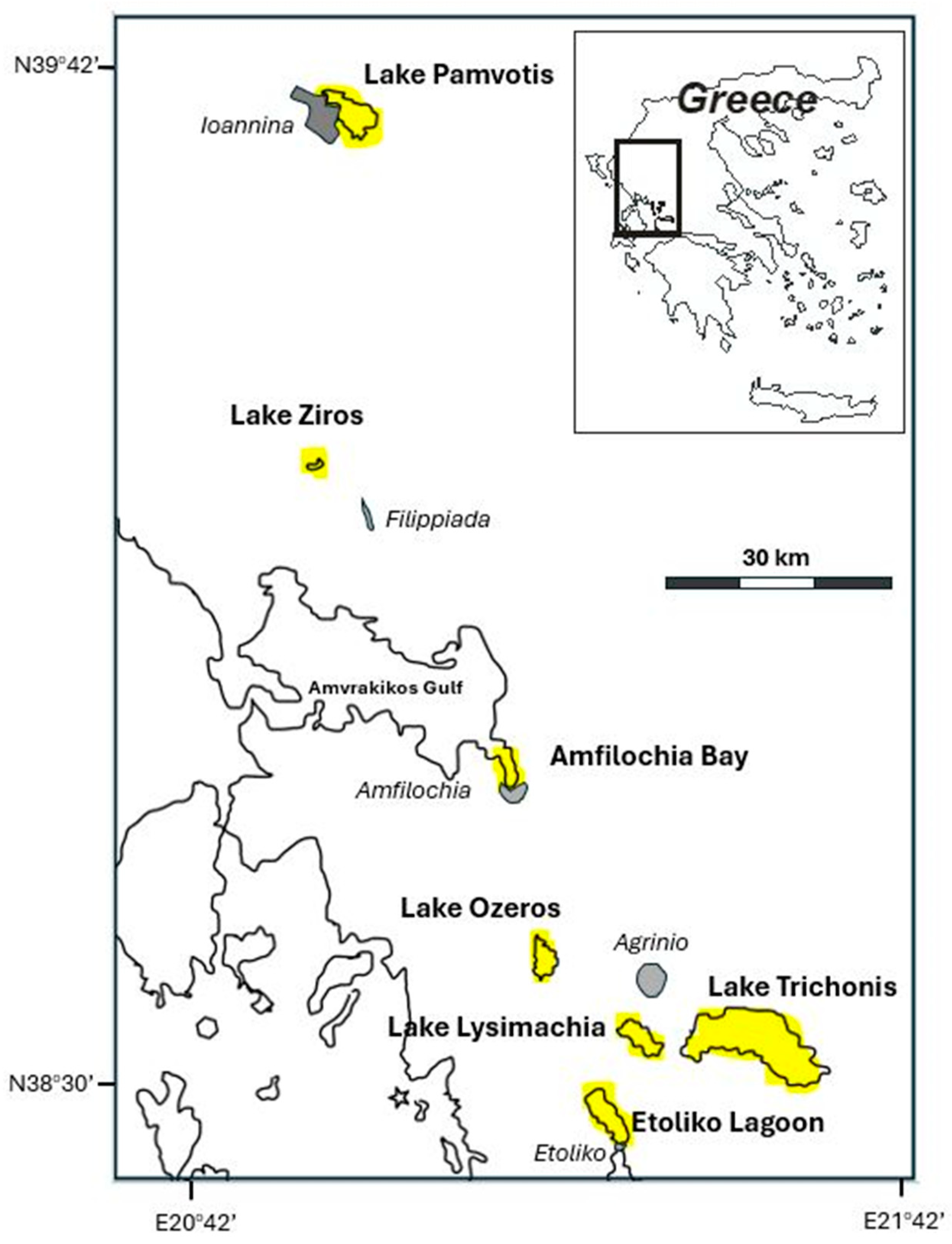

2.1. The Study Area

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Laboratory Measurements

3. Results

3.1. Abundance of Fibers and Fragments

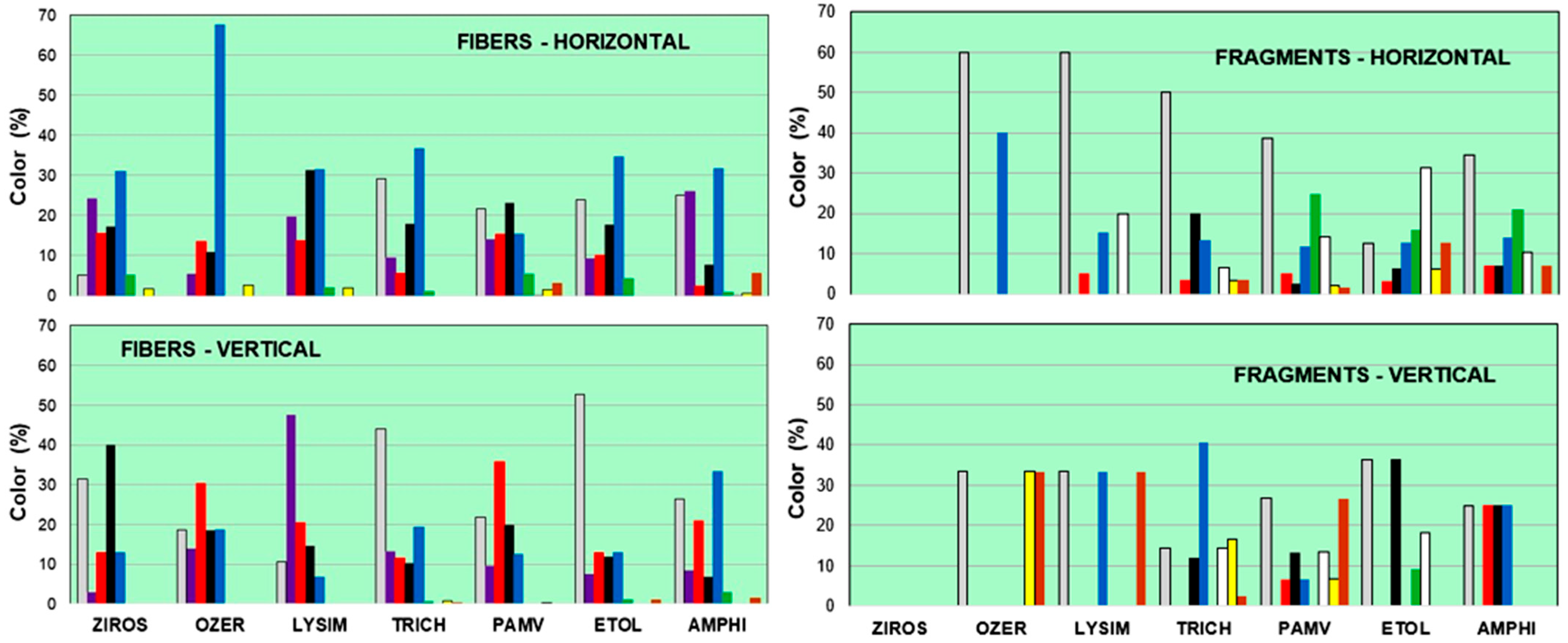

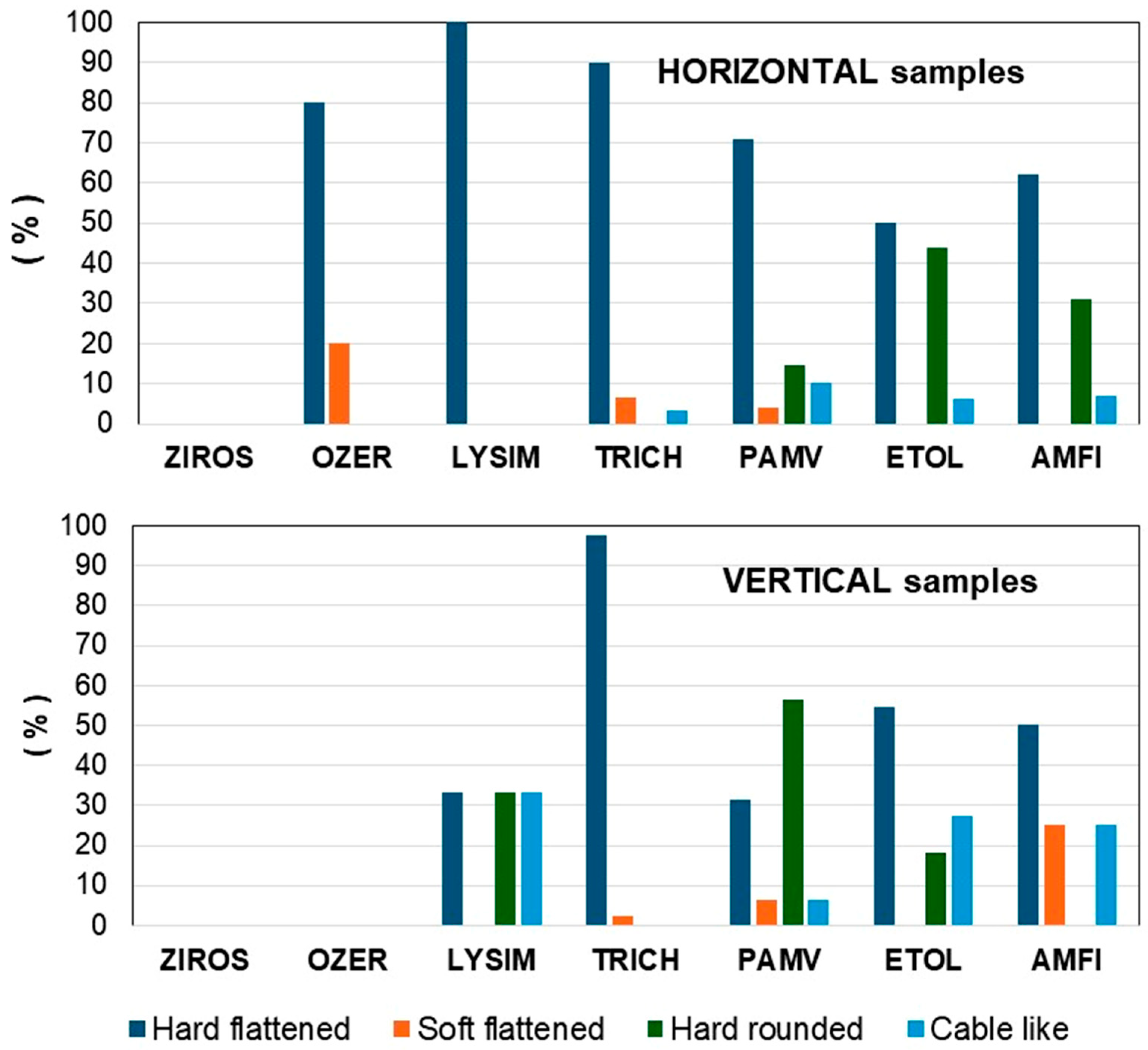

3.2. Color, Size, Shape, and Type of MPs

3.3. Correlation with Morphometrical and Sociological Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MP | Microplastic |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| RAP | Relative Anthropogenic Pressure |

| PVC | Polyvinyl chloride |

| FT-IR | Fourier transform infrared |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PA | Polyamide |

| PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| CTP | Closest town population |

| DFT | Distance from town |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- Bhowmik, A.; Saha, G. Microplastics in Our Waters: Insights from a Configurative Systematic Review of Water Bodies and Drinking Water Sources. Microplastics 2025, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolaosho, T.L.; Rasaq, M.F.; Omotoye, E.V.; Araomo, O.V.; Adekoya, O.S.; Abolaji, O.Y.; Hungbo, J.J. Microplastics in Freshwater and Marine Ecosystems: Occurrence, Characterization, Sources, Distribution Dynamics, Fate, Transport Processes, Potential Mitigation Strategies, and Policy Interventions. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 294, 118036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Liu, J.; Bao, M.; Fan, Y.; Kong, M. Microplastics in Lakes: Distribution Patterns and Influencing Factors. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 493, 138339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, P.R.; Parida, P.K.; Majhi, P.J.; Behera, B.K.; Das, B.K. Microplastics as Emerging Contaminants: Challenges in Inland Aquatic Food Web. Water 2025, 17, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strojny, W.; Gruca-Rokosz, R.; Cieśla, M. Microplastics in Water Resources: Threats and Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razeghi, N.; Hamidian, A.H.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, M. Microplastic Sampling Techniques in Freshwaters and Sediments: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 4225–4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Deng, C.; Dong, L.; Liu, L.; Li, H.; Wu, J.; Ye, C. Microplastic Pollution in the Yangtze River Basin: Heterogeneity of Abundances and Characteristics in Different Environments. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Richardson, R.E.; You, F. Microplastics Monitoring in Freshwater Systems: A Review of Global Efforts, Knowledge Gaps, and Research Priorities. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 477, 135329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, W.; Stasińska, E.; Żmijewska, A.; Więcko, A.; Zieliński, P. Litter per Liter–Lakes’ Morphology and Shoreline Urbanization Index as Factors of Microplastic Pollution: Study of 30 Lakes in NE Poland. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 881, 163426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wang, P.; Liu, S.; Wang, R.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, A.-X.; Deng, C. Global Patterns of Lake Microplastic Pollution: Insights from Regional Human Development Levels. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Alfy, M.A.; El-Hamid, H.T.A.; Keshta, A.E.; Elnaggar, A.A.; Darwish, D.H.; Alzeny, A.M.; Abou-Hadied, M.M.; Toubar, M.M.; Shalby, A.; Shabaka, S.H. Assessing Microplastic Pollution Vulnerability in a Protected Coastal Lagoon in the Mediterranean Coast of Egypt Using GIS Modeling. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gündoğdu, S.; Çevik, C.; Terzi, Y.; Gedik, K.; Büyükdeveci, F.; Öztürk, R.Ç. Microplastics in Turkish Coastal Lagoons: Unveiling the Hidden Threat to Wetland Ecosystems. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 375, 126351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perraki, M.; Skliros, V.; Mecaj, P.; Vasileiou, E.; Salmas, C.; Papanikolaou, I.; Stamatis, G. Identification of Microplastics Using Μ-Raman Spectroscopy in Surface and Groundwater Bodies of SE Attica, Greece. Water 2024, 16, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmas, C.; Alexopoulos, K.; Papanikolaou, I.; Vasileiou, E.; Perraki, M. Microplastics Identification in Remote Aquatic Environments Using Raman Spectroscopy: A Case Study for Mt. Tymfi’s Alpine Lake. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2025, 56, 1315–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doulka, E.; Kehayias, G. Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Zooplankton in Lake Trichonis (Greece). J. Nat. Hist. 2008, 42, 575–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, I.; Dimitriou, E.; Koussouris, T. Integrated Water Management Scenarios for Wetland Protection: Application in Trichonis Lake. Environ. Model. Softw. 2005, 20, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalkia, E.; Kehayias, G. Zooplankton and Environmental Factors of a Recovering Eutrophic Lake (Lysimachia Lake, Western Greece). Biologia 2013, 68, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latinopoulos, D.; Koulouri, M.; Kagalou, I. How Historical Land Use/Land Cover Changes Affected Ecosystem Services in Lake Pamvotis, Greece. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2021, 27, 1472–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagalou, I.; Psilovikos, A. Assessment of the Typology and the Trophic Status of Two Mediterranean Lake Ecosystems in Northwestern Greece. Water Resour. 2014, 41, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianni, A.; Str, S.; Zacharias, I. Temporal and Spatial Distribution of Physico-Chemical Parameters in an Anoxic Lagoon, Aitoliko, Greece. J. Environ. Biol. 2012, 33, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kehayias, G.; Aposporis, M. Zooplankton Variation in Relation to Hydrology in an Enclosed Hypoxic Bay (Amvrakikos Gulf, Greece). Medit. Mar. Sci. 2014, 15, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilopoulou, G.; Kehayias, G.; Kletou, D.; Kleitou, P.; Triantafyllidis, V.; Zotos, A.; Antoniadis, K.; Rousou, M.; Papadopoulos, V.; Polykarpou, P.; et al. Microplastics Investigation Using Zooplankton Samples from the Coasts of Cyprus (Eastern Mediterranean). Water 2021, 13, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsikos, N.; Koi, A.M.; Zeri, C.; Tsangaris, C.; Dimitriou, E.; Kalantzi, O.-I. Exploring Microplastic Pollution in a Mediterranean River: The Role of Introduced Species as Bioindicators. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharath, K.M.; Srinivasalu, S.; Natesan, U.; Ayyamperumal, R.; Nirmal Kalam, S.; Anbalagan, S.; Sujatha, K.; Alagarasan, C. Microplastics as an Emerging Threat to the Freshwater Ecosystems of Veeranam Lake in South India: A Multidimensional Approach. Chemosphere 2021, 264, 128502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celis-Hernandez, O.; Ávila, E.; Rendón-von Osten, J.; Briceño-Vera, E.A.; Borges-Ramírez, M.M.; Gómez-Ponce, A.M.; Capparelli, V.M. Environmental Risk of Microplastics in a Mexican Coastal Lagoon Ecosystem: Anthropogenic Inputs and Its Possible Human Food Risk. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 879, 163095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowszys, M. Microplastics in the waters of European lakes and their potential effect on food webs: A review. Pol. J. Nat. Sci. 2022, 37, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla-Pradhan, R.; Pradhan, B.L.; Phoungthong, K.; Joshi, T.P. Microplastic in Freshwater Environment: A Review on Techniques and Abundance for Microplastic Detection in Lake Water. Trends Sci. 2023, 20, 5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, W.; Yu, H.; Hai, C.; Wang, Y.; Yu, S.; Tsedevdorj, S.-O. Research Status and Prospects of Microplastic Pollution in Lakes. Environ. Monit Assess 2023, 195, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindeque, P.K.; Cole, M.; Coppock, R.L.; Lewis, C.N.; Miller, R.Z.; Watts, A.J.R.; Wilson-McNeal, A.; Wright, S.L.; Galloway, T.S. Are We Underestimating Microplastic Abundance in the Marine Environment? A Comparison of Microplastic Capture with Nets of Different Mesh-Size. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265, 114721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, M.; Dhanker, R.; Sharma, N.; Kamakshi; Kamble, S.S.; Tiwari, A.; Du, Z.-Y.; Mohamed, H.I. Responses of Natural Plastisphere Community and Zooplankton to Microplastic Pollution: A Review on Novel Remediation Strategies. Arch. Microbiol. 2025, 207, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solayman, H.M.; Robby, M.D.A.; Satriaji, F.V.; Hossain, M.K.; Kang, K.; Aziz, A.A.; Shiu, R.-F.; Jiang, J.-J. Mapping Global Microplastic Pollution: Integrating Advanced Detection and Monitoring in Aquatic Ecosystems. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2026, 222, 118685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés-Ordóñez, O.; Saldarriaga-Vélez, J.F.; Espinosa-Díaz, L.F.; Canals, M.; Sánchez-Vidal, A.; Thiel, M. A Systematic Review on Microplastic Pollution in Water, Sediments, and Organisms from 50 Coastal Lagoons across the Globe. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 315, 120366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, T.; Liao, H.; Yang, F.; Sun, F.; Guo, Y.; Yang, H.; Feng, D.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Q. Review of Microplastics in Lakes: Sources, Distribution Characteristics, and Environmental Effects. Carbon Res. 2023, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Tian, X.; Zhao, R.; Wang, B.; Qi, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Shan, B. Spatiotemporal and Vertical Distribution Characteristics and Ecological Risks of Microplastics in Typical Shallow Lakes in Northern China. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 382, 126773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Ruz, V.; Gutow, L.; Thompson, R.C.; Thiel, M. Microplastics in the Marine Environment: A Review of the Methods Used for Identification and Quantification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 3060–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamminga, M.; Fischer, E.K. Microplastics in a Deep, Dimictic Lake of the North German Plain with Special Regard to Vertical Distribution Patterns. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 267, 115507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Xu, X.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, L.; Guo, J.; Wang, L.; Peng, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, Y. Horizontal and Vertical Distribution of Microplastics in Gehu Lake, China. Water Supply 2022, 22, 8669–8681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, S.C.; Glassic, H.C.; Guy, C.S.; Koel, T.M. Presence of Microplastics in the Food Web of the Largest High-Elevation Lake in North America. Water 2021, 13, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenaker, P.L.; Baldwin, A.K.; Corsi, S.R.; Mason, S.A.; Reneau, P.C.; Scott, J.W. Vertical Distribution of Microplastics in the Water Column and Surficial Sediment from the Milwaukee River Basin to Lake Michigan. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 12227–12237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Cai, Y.; Liao, Y.; Liu, L.; Tang, Y. Revealing Microplastic Risks in Stratified Water Columns of the East China Sea Offshore. Water Res. 2025, 271, 122900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malygina, N.; Mitrofanova, E.; Kuryatnikova, N.; Biryukov, R.; Zolotov, D.; Pershin, D.; Chernykh, D. Microplastic Pollution in the Surface Waters from Plain and Mountainous Lakes in Siberia, Russia. Water 2021, 13, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangeliou, N.; Grythe, H.; Klimont, Z.; Heyes, C.; Eckhardt, S.; Lopez-Aparicio, S.; Stohl, A. Atmospheric Transport Is a Major Pathway of Microplastics to Remote Regions. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padha, S.; Kumar, R.; Dhar, A.; Sharma, P. Microplastic Pollution in Mountain Terrains and Foothills: A Review on Source, Extraction, and Distribution of Microplastics in Remote Areas. Environ. Res. 2022, 207, 112232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliszewicz, A.; Winczek, M.; Karaban, K.; Kurzydłowski, D.; Górska, M.; Koselak, W.; Romanowski, J. The Contamination of Inland Waters by Microplastic Fibres under Different Anthropogenic Pressure: Preliminary Study in Central Europe (Poland). Waste Manag. Res. 2020, 38, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Yee Leung, K.M.; Wu, F. Color: An Important but Overlooked Factor for Plastic Photoaging and Microplastic Formation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 9161–9163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, L.M.; Da Silva, T.C.; Pimentel, A.A.; Do Rosário Ramos, K.; Da Silva, L.M.A.; Souza, A.C.F.; De Souza Gama, C. Intake of Microplastics by Fishes in a Floodplain Lake of the Curiaú River (Macapá, Amapá, Brazil). Aquat. Sci. 2025, 87, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Luna, R.A.; Oquendo-Ruiz, L.; García-Alzate, C.A.; Arana, V.A.; García-Alzate, R.; Trilleras, J. Methods to Characterize Microplastics: Case Study on Freshwater Fishes from a Tropical Lagoon in Colombia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 64171–64184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğan, Ş. Microplastic Contamination in Freshwater Fish: First Insights from Gelingüllü Reservoir (Türkiye). Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagha, P.L.; Viji, N.V.; Devika, D.; Ramasamy, E.V. Distribution and Abundance of Microplastics in the Water Column of Vembanad Lake–A Ramsar Site in Kerala, India. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 194, 115433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorino, P.; Anselmi, S.; Esposito, G.; Bertoli, M.; Pizzul, E.; Barceló, D.; Elia, A.C.; Dondo, A.; Prearo, M.; Renzi, M. Microplastics in Biotic and Abiotic Compartments of High-Mountain Lakes from Alps. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 150, 110215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanentzap, A.J.; Cottingham, S.; Fonvielle, J.; Riley, I.; Walker, L.M.; Woodman, S.G.; Kontou, D.; Pichler, C.M.; Reisner, E.; Lebreton, L. Microplastics and Anthropogenic Fibre Concentrations in Lakes Reflect Surrounding Land Use. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Geng, S.; Wu, C.; Song, K.; Sun, F.; Visvanathan, C.; Xie, F.; Wang, Q. Microplastics Contamination in Different Trophic State Lakes along the Middle and Lower Reaches of Yangtze River Basin. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 112951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Aquatic Ecosystem | Area (km3) | Catchment Area (km2) | Max Depth (m) | Trophic Cond. * | Closest Town | Town Popul. ** | Dist. from Town (km) | Human Activities *** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZIROS | 0.4 | 1.25 | 56 | M | Filipiada | 5207 | 3 | C |

| OZEROS | 9.5 | 59 | 6 | Μ-Ε | Agrinio | 50,690 | 14 | A, F |

| LYSIMACHIA | 13.1 | 246 | 8 | Ε | Agrinio | 50,690 | 3 | A, F |

| TRICHONIS | 95.8 | 400 | 58 | O-Μ | Agrinio | 50,690 | 6 | A, F, WS |

| PAMVOTIS | 19.5 | 531 | 5 | Ε | Ioannina | 64,896 | 0.1 | A, F, WS, MW, H, WT |

| ETOLIKO | 17.0 | 250 | 27 | Ε | Etoliko | 4813 | 0.1 | A, F |

| AMFILOCHIA | 20.0 | 120 | 35 | Ε | Amfilochia | 4241 | 0.1 | F, MW, H |

| Parameter | Area | Catchment Area | Max Depth | Closest Town Population (CTP) | Distance from Town (DFT) | Relative Anthropogenic Pressure (RAP) | r2 | d.f. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibres (horizontal) | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | 0.956 ** | 0.914 | 5 |

| Fragments (horizontal) | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | 0.843 * | 0.710 | 5 |

| Fibres (vertical) | ns | ns | ns | 0.875 * | −0.506 * | ns | 0.960 | 5 |

| Fragments (vertical) | ns | ns | ns | 0.678 * | ns | 0.576 * | 0.915 | 5 |

| Fibres & Fragments (horiz.) | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | 0.956 ** | 0.914 | 5 |

| Fibres & Fragments (vert.) | ns | ns | ns | 0.801 ** | ns | 0.453 ** | 0.962 | 5 |

| Fibres & Fragments | ns | ns | ns | 0.758 ** | ns | 0.522 ** | 0.973 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kehayias, G.; Kanellopoulou, P.; Kechagias, A.; Giannakas, A.E.; Salmas, C.E.; Maimaris, T.N.; Karakassides, M.A. Comparative Distribution of Microplastics in Different Inland Aquatic Ecosystems. Water 2025, 17, 3432. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233432

Kehayias G, Kanellopoulou P, Kechagias A, Giannakas AE, Salmas CE, Maimaris TN, Karakassides MA. Comparative Distribution of Microplastics in Different Inland Aquatic Ecosystems. Water. 2025; 17(23):3432. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233432

Chicago/Turabian StyleKehayias, George, Penelope Kanellopoulou, Achilleas Kechagias, Aris E. Giannakas, Constantinos E. Salmas, Theofanis N. Maimaris, and Michael A. Karakassides. 2025. "Comparative Distribution of Microplastics in Different Inland Aquatic Ecosystems" Water 17, no. 23: 3432. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233432

APA StyleKehayias, G., Kanellopoulou, P., Kechagias, A., Giannakas, A. E., Salmas, C. E., Maimaris, T. N., & Karakassides, M. A. (2025). Comparative Distribution of Microplastics in Different Inland Aquatic Ecosystems. Water, 17(23), 3432. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233432