Performance Evaluation of the SRM and GRxJ—CemaNeige Models for Daily Streamflow Simulation in Two Catchments with Snow and Rain Dominated Hydrological Regimes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Hydrometeorological Data

2.3. Satellite Data

MODIS

2.4. Hydrological Models

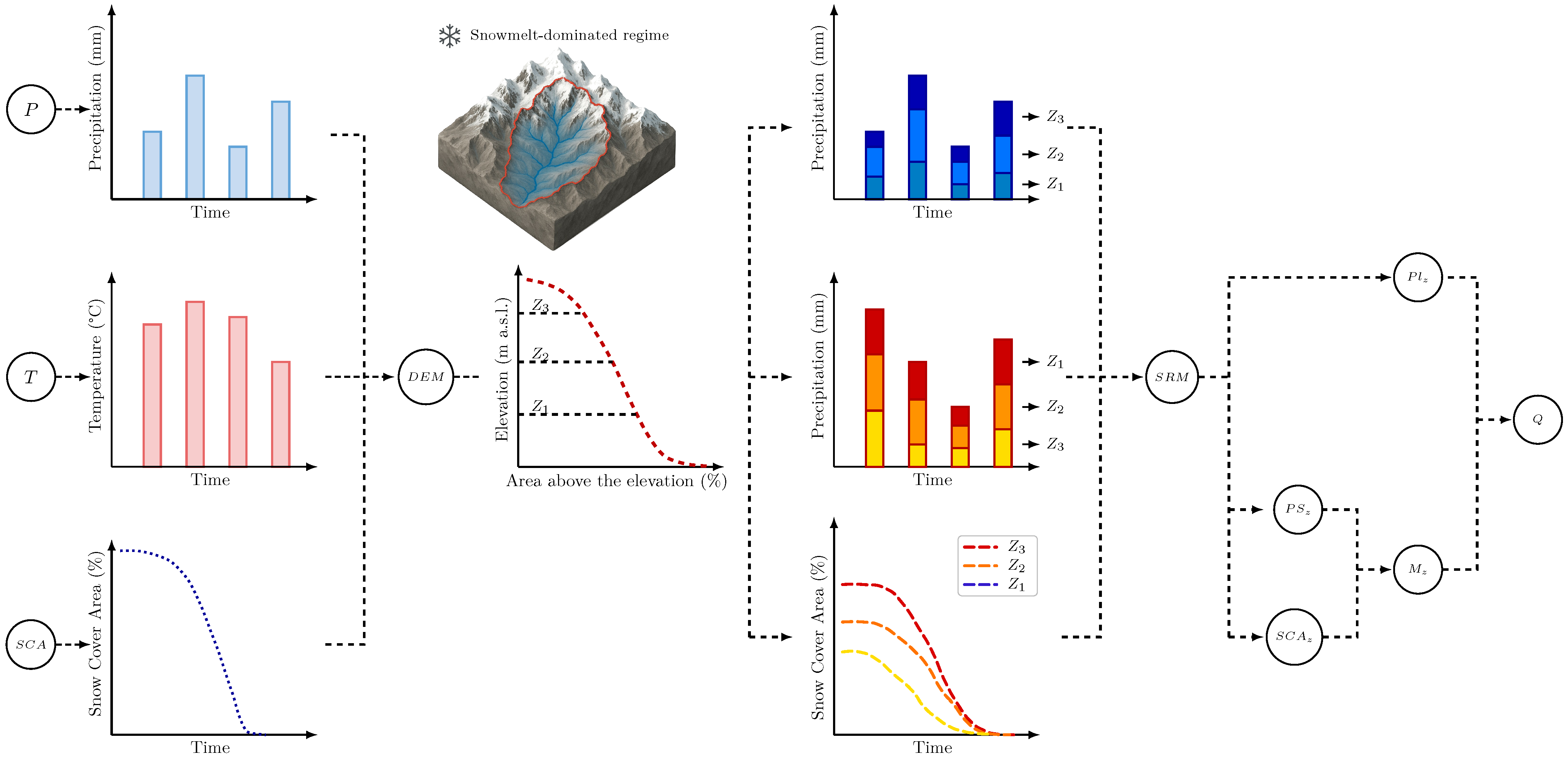

2.4.1. SRM (Snowmelt-Runoff Model)

2.4.2. GRxJ Models (GR4J, GR5J, GR6J) and the CemaNeige Module

2.5. Calibration Strategy

2.6. Model Efficiency Indicators

3. Results

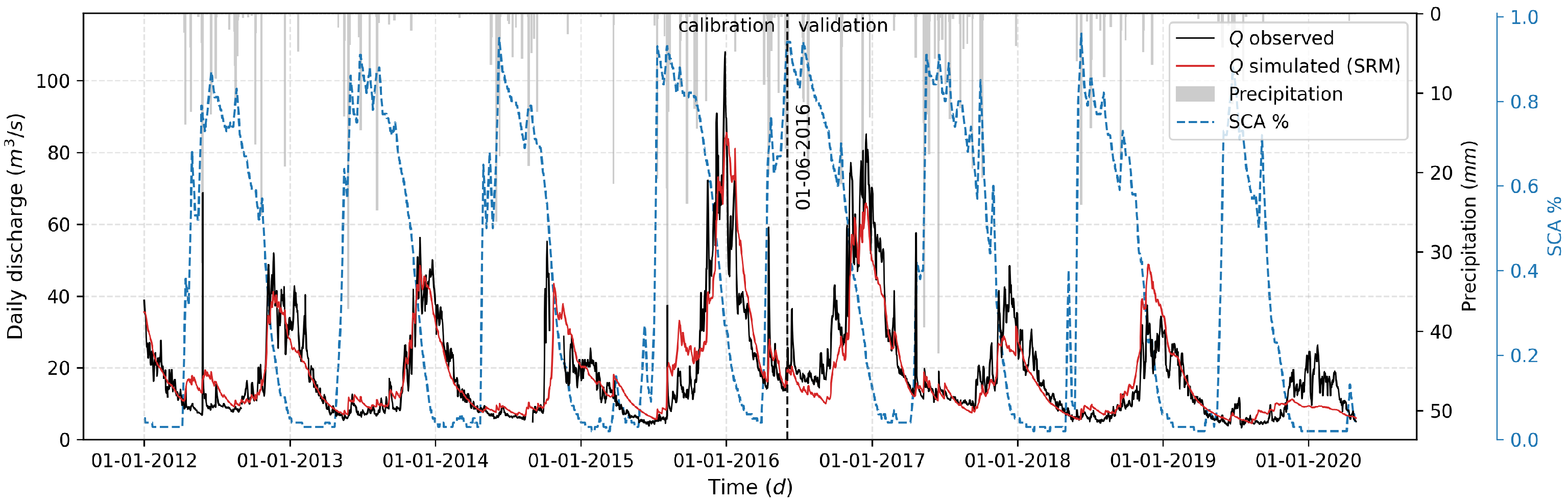

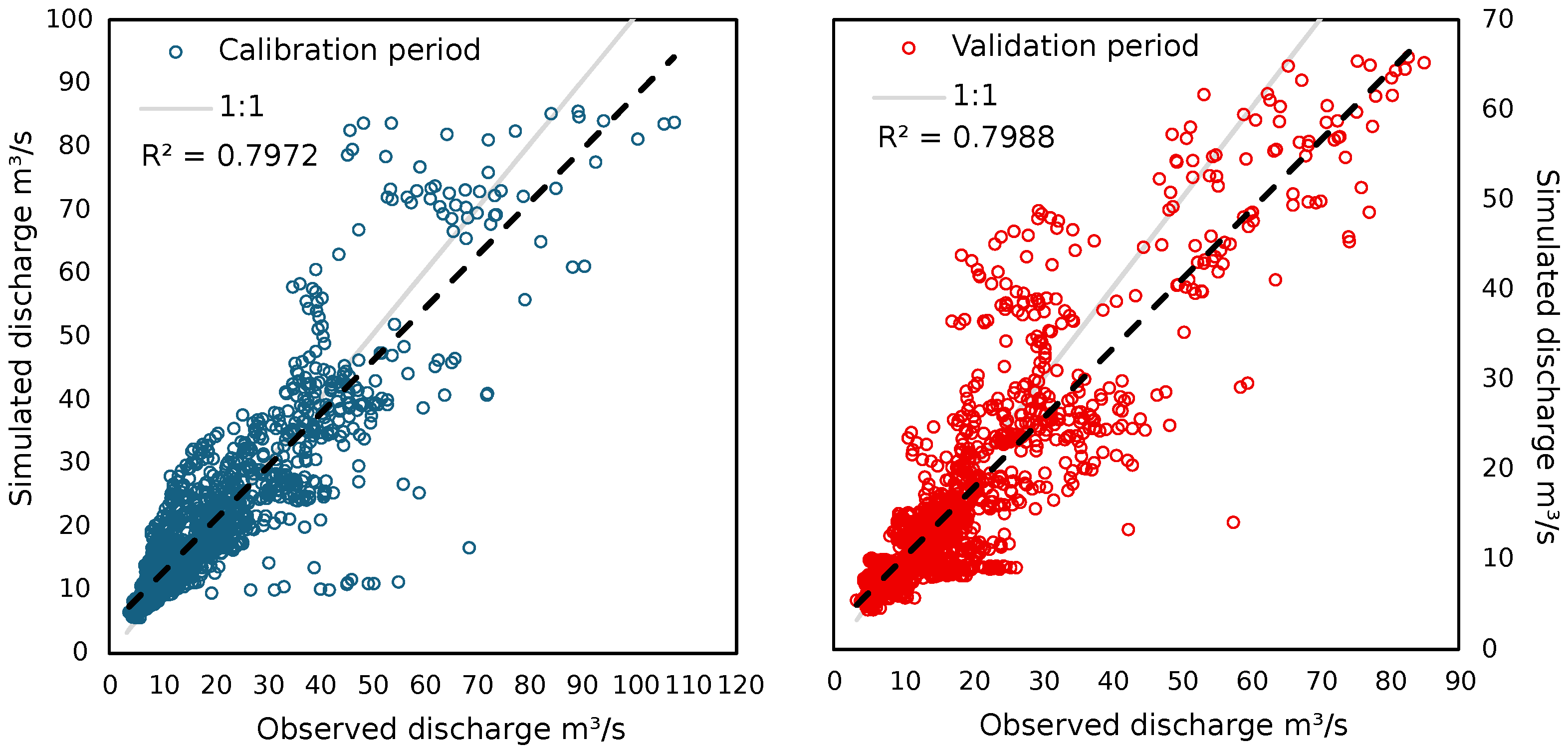

3.1. Snowmelt-Runoff Model

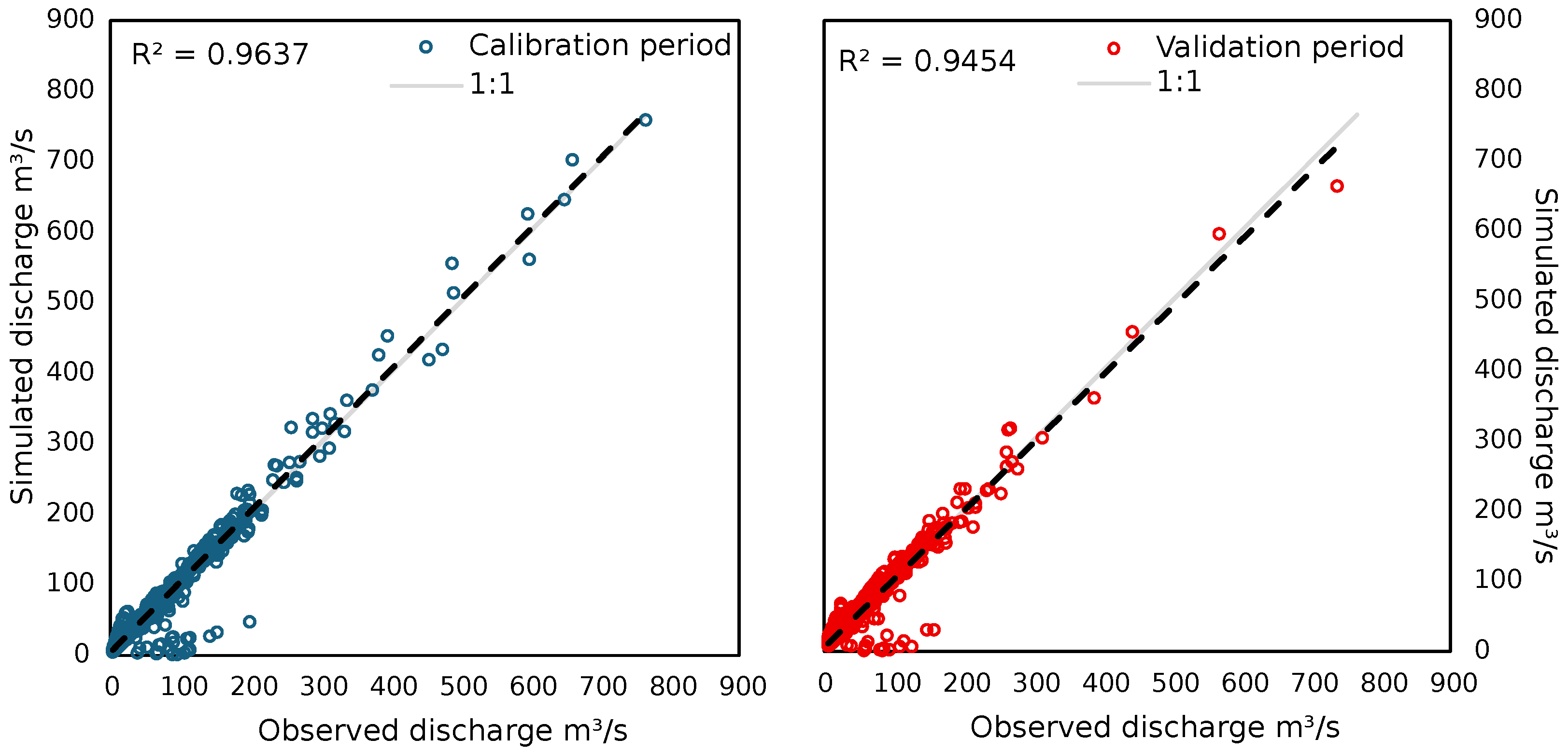

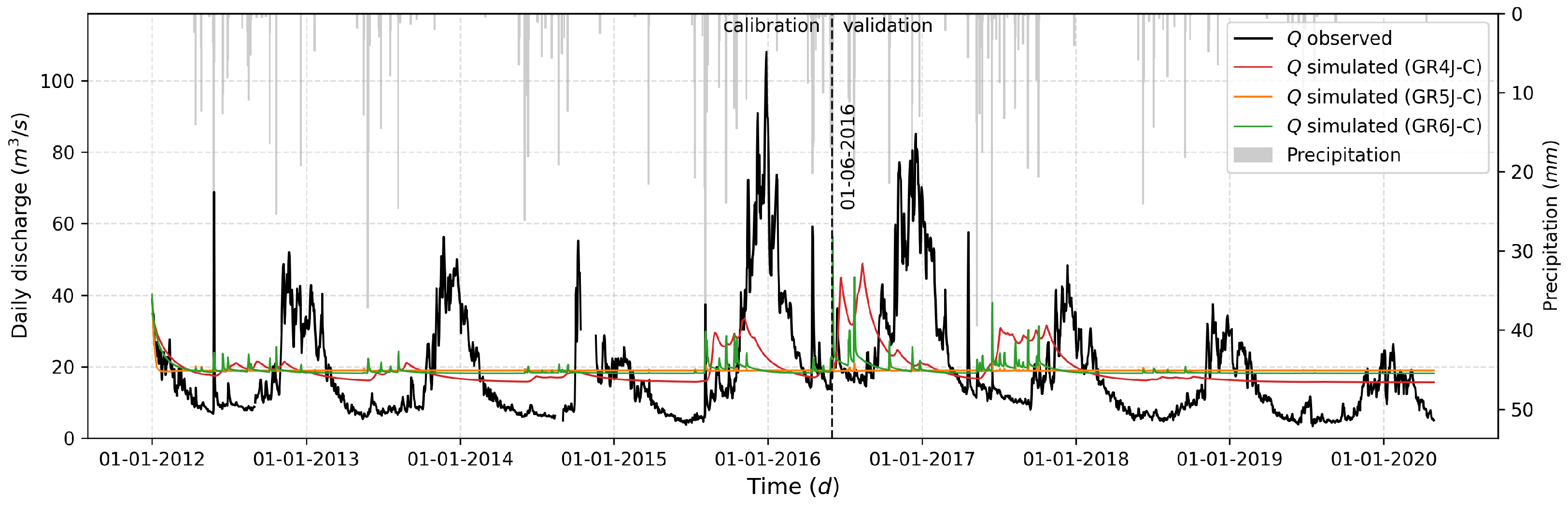

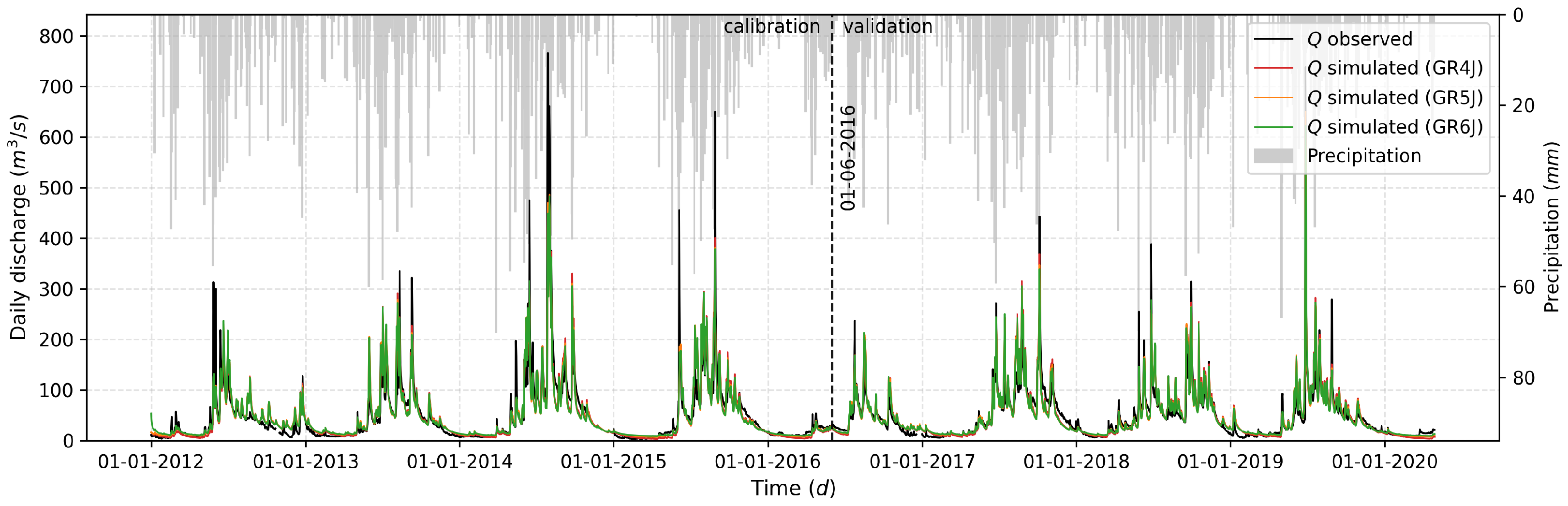

3.2. GRxJ Models (GR4J, GR5J, GR6J) with and Without the CemaNeige Module

3.2.1. Selection of the Evapotranspiration Model That Optimizes Model Performance

3.2.2. Model Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Performance of Both Models

4.1.1. Aconcagua River in Chacabuquito

4.1.2. Duqueco River in Cerrillos

4.2. Influence of the PET Source on GRxJ Models’ Performance

4.3. Comparison of GR4J, GR5J, and GR6J Performance with and Without the CemaNeige Module

4.4. Performance of Both Models in Previous Studies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| a.s.l. | above sea level |

| airGR | R package for GR models |

| BNA | Banco Nacional de Aforos (Chile’s National Hydrometric Database) |

| CAMELS-CL | Catchment Attributes and Meteorology for Large-sample Studies—Chile |

| CemaNeige | Snow accounting routine (degree–day snow module for GR models) |

| CR2 | Center for Climate and Resilience Research (Chile) |

| DGA | Dirección General de Aguas (Chilean Water Authority) |

| ESDS | (NASA) Earth Science Data Systems |

| GA | Genetic algorithm |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| GR4J | Génie Rural daily rainfall–runoff model (4 parameters) |

| GR5J | Génie Rural daily rainfall–runoff model (5 parameters) |

| GR6J | Génie Rural daily rainfall–runoff model (6 parameters) |

| GRxJ | Family of GR daily rainfall–runoff models () |

| KGE | Kling–Gupta Efficiency |

| MOD09A1 | MODIS Terra Surface Reflectance (8-day, 500 m) product |

| MODIS | Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| NDSI | Normalized Difference Snow Index |

| NSE | Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency |

| PBIAS | Percent Bias |

| PET | Potential Evapotranspiration |

| R | The R programming language |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| SAR | Snow Accounting Routine (in CemaNeige) |

| SCA | Snow Cover Area |

| SRM | Snowmelt-Runoff Model |

| SWIR | Shortwave Infrared |

| UH | Unit hydrograph |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Parameter (Monthly Average) | Zone | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| a | 0.8971 | 0.3096 | 0.3102 | 0.4670 | 0.8406 | 0.6885 | 0.7906 | 0.8684 | 0.4537 |

| y | 0.6390 | 0.6357 | 0.6389 | 0.6903 | 0.6979 | 0.4066 | 0.5149 | 0.5237 | 0.5932 |

| 0.3760 | 0.1881 | 0.2798 | 0.2574 | 0.6699 | 0.2191 | 0.6361 | 0.9985 | 0.1273 | |

| 0.2461 | 0.0347 | 0.0086 | 0.0659 | 0.0562 | 0.0216 | 0.8936 | 0.6047 | 0.3107 | |

| 3.7922 | 1.5207 | 3.5385 | 2.6962 | 2.7044 | 2.4480 | 2.0601 | 0.5653 | 3.9698 | |

| X | 1.1339 | ||||||||

| Y | 0.0480 | ||||||||

Appendix A.2

| Parameter | Zone | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| a | 0.4858 | 0.9890 | 0.2228 | 0.5453 | 0.3100 | 0.1577 |

| y | 0.6578 | 0.8510 | 0.9487 | 0.9006 | 0.8720 | 0.8256 |

| 0.5953 | 0.0045 | 0.0264 | 0.1228 | 0.8093 | 0.0250 | |

| 0.0136 | 0.0016 | 0.0073 | 0.0172 | 0.4009 | 0.6573 | |

| 0.9747 | 3.0715 | 2.3894 | 3.4019 | 1.6414 | 2.8075 | |

| X | 0.5750 | |||||

| Y | 0.1810 | |||||

Appendix A.3

| Model | CemaNeige | GRxJ Parameters | CemaNeige Parameters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GR4J | Without | 323.0413 | 6.4915 | 92.4645 | 20.0000 | – | – | – | – |

| GR5J | Without | 614.8404 | −4.3659 | 233.2280 | 1.1625 | 0.4538 | – | – | – |

| GR6J | Without | 486.7449 | 0.5211 | 114.6054 | 1.2073 | −0.0888 | 0.3751 | – | – |

| GR4J | With | 298.0756 | 6.9339 | 101.6963 | 20.0000 | – | – | 0.0015 | 0.0878 |

| GR5J | With | 1548.6440 | −6.2439 | 218.5204 | 1.2664 | 0.4327 | – | 0.0015 | 0.0177 |

| GR6J | With | 455.1925 | 0.5211 | 114.8887 | 1.1971 | −0.0891 | 0.3814 | 0.7052 | 0.0857 |

Appendix A.4

| Model | CemaNeige | GRxJ Parameters | CemaNeige Parameters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GR4J | Without | 1032.7702 | 2.0369 | 112.1683 | 2.0030 | – | – | – | – |

| GR5J | Without | 885.8531 | 0.6728 | 102.3547 | 1.5445 | 0.0991 | – | – | – |

| GR6J | Without | 796.8922 | 0.1472 | 118.9345 | 2.1298 | −0.8336 | 3.2755 | – | – |

| GR4J | With | 665.1416 | 2.0597 | 117.9192 | 1.9932 | – | – | 0.0105 | 2.0786 |

| GR5J | With | 589.5081 | −0.5694 | 119.4266 | 1.5082 | 1.0000 | – | 0.0425 | 20.7294 |

| GR6J | With | 543.5959 | 0.1482 | 51.9194 | 2.0492 | −0.5749 | 11.5934 | 0.0913 | 7.4759 |

References

- Basso, S.; Botter, G. Streamflow variability and optimal capacity of run-of-river hydropower plants. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, P.; Chen, X.; Guan, Y. A multivariate conditional model for streamflow prediction and spatial precipitation refinement. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2015, 120, 10116–10129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketchum, D.; Hoylman, Z.H.; Huntington, J.; Brinkerhoff, D.; Jencso, K.G. Irrigation intensification impacts sustainability of streamflow in the Western United States. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Kedam, N.; Sharma, K.V.; Mehta, D.J.; Caloiero, T. Advanced Machine Learning Techniques to Improve Hydrological Prediction: A Comparative Analysis of Streamflow Prediction Models. Water 2023, 15, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhasme, P.; Bhatia, U. Improving the interpretability and predictive power of hydrological models: Applications for daily streamflow in managed and unmanaged catchments. J. Hydrol. 2024, 628, 130421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, J.L.; Niswonger, R.G. Role of surface-water and groundwater interactions on projected summertime streamflow in snow dominated regions: An integrated modeling approach. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, R.; Banzhaf, S. Groundwater and Surface Water Interaction at the Regional-scale—A Review with Focus on Regional Integrated Models. Water Resour. Manag. 2015, 30, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Cui, P.; Gualtieri, C.; Zhang, J.; Ahmed Bazai, N.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Tang, J.; Chen, R.; Lei, M. Stormflow generation in a humid forest watershed controlled by antecedent wetness and rainfall amounts. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 127107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Cui, P.; Gualtieri, C.; Bazai, N.A.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z. Increased nonstationarity of stormflow threshold behaviors in a forested watershed due to abrupt earthquake disturbance. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 3005–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, M.S.; Bhat, S.U.; Rashid, I.; Kuniyal, J.C. Socioeconomic Aspect of Disaster Risk in Kashmir: Contextualizing Village Vulnerability in Sindh Basin. In Climate Change Adaptation, Risk Management and Sustainable Practices in the Himalaya; Sharma, S., Kuniyal, J.C., Chand, P., Singh, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongley, T.; Thakur, P.K.; Khajuria, V.; Bhattarai, N.; Choden, K.; Chokila, C. Estimation of glacier dynamics of the major glaciers of Bhutan using geospatial techniques. J. Water Clim. Change 2023, 14, 2825–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Gupta, J.; Qin, D.; Lade, S.J.; Abrams, J.F.; Andersen, L.S.; Armstrong McKay, D.I.; Bai, X.; Bala, G.; Bunn, S.E.; et al. Safe and just Earth system boundaries. Nature 2023, 619, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliavacca, F.; Confortola, G.; Soncini, A.; Senese, A.; Diolaiuti, G.A.; Smiraglia, C.; Barcaza, G.; Bocchiola, D. Hydrology and potential climate changes in the Rio Maipo (Chile). Geogr. Fis. E Din. Quat. 2015, 38, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, K.I.; Baraër, M.; Mark, B.G.; Ahn, Y. Evaluating Glacier Volume Changes since the Little Ice Age Maximum and Consequences for Stream Flow by Integrating Models of Glacier Flow and Hydrology in the Cordillera Blanca, Peruvian Andes. Water 2018, 10, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koneti, S.; Sunkara, S.; Roy, P. Hydrological Modeling with Respect to Impact of Land-Use and Land-Cover Change on the Runoff Dynamics in Godavari River Basin Using the HEC-HMS Model. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysanova, V.; Donnelly, C.; Gelfan, A.; Gerten, D.; Arheimer, B.; Hattermann, F.; Kundzewicz, Z.W. How the performance of hydrological models relates to credibility of projections under climate change. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2018, 63, 696–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Pappenberger, F.; Wood, A.; Cloke, H.L.; Schaake, J.C. (Eds.) Handbook of Hydrometeorological Ensemble Forecasting, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrachowitz, M.; Clark, M.P. HESS Opinions: The complementary merits of competing modelling philosophies in hydrology. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 3953–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemri, S.; Kinnard, C. Comparing calibration strategies of a conceptual snow hydrology model and their impact on model performance and parameter identifiability. J. Hydrol. 2020, 582, 124474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficklin, D.L.; Barnhart, B.L. SWAT hydrologic model parameter uncertainty and its implications for hydroclimatic projections in snowmelt-dependent watersheds. J. Hydrol. 2014, 519, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenault, R.; Brissette, F.P. Continuous streamflow prediction in ungauged basins: The effects of equifinality and parameter set selection on uncertainty in regionalization approaches. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 6135–6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rango, A.; Martinec, J.; Roberts, R. Relative importance of glacier contributions to streamflow in a changing climate. In Proceedings of the Second IASTED International Conference on Water Resource Management, Honolulu, HI, USA, 20–22 August 2007; ISBN 978-0-88986-680-5. [Google Scholar]

- Panday, P.K.; Williams, C.A.; Frey, K.E.; Brown, M.E. Application and evaluation of a snowmelt runoff model in the Tamor River basin, Eastern Himalaya using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) data assimilation approach. Hydrol. Process. 2013, 28, 5337–5353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, A.A.; Chevallier, P.; Arnaud, Y.; Neppel, L.; Ahmad, B. Modeling snowmelt-runoff under climate scenarios in the Hunza River basin, Karakoram Range, Northern Pakistan. J. Hydrol. 2011, 409, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpalatha, R.; Perrin, C.; Le Moine, N.; Mathevet, T.; Andréassian, V. A downward structural sensitivity analysis of hydrological models to improve low-flow simulation. J. Hydrol. 2011, 411, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valéry, A.; Andréassian, V.; Perrin, C. ‘As simple as possible but not simpler’: What is useful in a temperature-based snow-accounting routine? Part 1—Comparison of six snow accounting routines on 380 catchments. J. Hydrol. 2014, 517, 1166–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valéry, A.; Andréassian, V.; Perrin, C. ‘As simple as possible but not simpler’: What is useful in a temperature-based snow-accounting routine? Part 2—Sensitivity analysis of the Cemaneige snow accounting routine on 380 catchments. J. Hydrol. 2014, 517, 1176–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escanilla-Minchel, R.; Alcayaga, H.; Soto-Alvarez, M.; Kinnard, C.; Urrutia, R. Evaluation of the Impact of Climate Change on Runoff Generation in an Andean Glacier Watershed. Water 2020, 12, 3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, N.; Rodríguez, R.; Yépez, S.; Osores, V.; Rau, P.; Rivera, D.; Balocchi, F. Comparison of Three Daily Rainfall-Runoff Hydrological Models Using Four Evapotranspiration Models in Four Small Forested Watersheds with Different Land Cover in South-Central Chile. Water 2021, 13, 3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, M.J.; Winter, J.M.; Spera, S.A.; Chipman, J.W.; Osterberg, E.C. Water, agriculture, and climate dynamics in central Chile’s Aconcagua River Basin. Phys. Geogr. 2020, 42, 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bown, F.; Rivera, A.; Acuña, C. Recent glacier variations at the Aconcagua basin, central Chilean Andes. Ann. Glaciol. 2008, 48, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, C.; Fernández, A.; Rubio, P. Caudales y variabilidad climática en una cuenca de latitudes medias en Sudamérica: Río Aconcagua, Chile Central (33ºS). Bol. Asoc. Geógr. Esp. 2012, 58, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yépez, S.; Salas, F.; Nardini, A.; Valenzuela, N.; Osores, V.; Vargas, J.; Rodríguez, R.; Piégay, H. Semi-automated morphological characterization using South Rivers Toolbox. Proc. IAHS 2024, 385, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirección General de Aguas. Balance hídrico de Chile; Recursos Hídricos DGA, Ministerio de Obras Públicas (MOP): Santiago, Chile, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Garreton, C.; Mendoza, P.A.; Boisier, J.P.; Addor, N.; Galleguillos, M.; Zambrano-Bigiarini, M.; Lara, A.; Puelma, C.; Cortes, G.; Garreaud, R.; et al. The CAMELS-CL dataset: Catchment attributes and meteorology for large sample studies—Chile dataset. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 5817–5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudin, L.; Hervieu, F.; Michel, C.; Perrin, C.; Andréassian, V.; Anctil, F.; Loumagne, C. Which potential evapotranspiration input for a lumped rainfall–runoff model? J. Hydrol. 2005, 303, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, G.H.; Samani, Z.A. Estimating Potential Evapotranspiration. J. Irrig. Drain. Div. 1982, 108, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, C.H.B.; Taylor, R.J. On the Assessment of Surface Heat Flux and Evaporation Using Large-Scale Parameters. Mon. Weather Rev. 1972, 100, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhomme, J.P. A theoretical basis for The Priestley—Taylor Coefficient. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 1997, 82, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermote, E. MODIS/Terra Surface Reflectance 8-Day L3 Global 500m SIN Grid V061. 2021. Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-mod09a1-061 (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Riggs, G.; Barton, J.; Casey, K.; Hall, D.; Salomonson, V. MODIS Snow Products User Guide. 2006. Available online: https://modis-snow-ice.gsfc.nasa.gov/uploads/sug_c5.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Härer, S.; Bernhardt, M.; Siebers, M.; Schulz, K. On the need for a time- and location-dependent estimation of the NDSI threshold value for reducing existing uncertainties in snow cover maps at different scales. Cryosphere 2018, 12, 1629–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinec, J. Snowmelt—Runoff Model for stream flow forecasts. Hydrol. Res. 1975, 6, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinec, J.; Rango, A.; Major, E. The Snowmelt-Runoff Model (SRM) User’s Manual; NASA Reference Publication NASA-RP-1100; National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA): Washington, DC, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Le Moine, N. Le Bassin Versant de Surface vu par le Souterrain: Une voie D’amélioration des Performances et du Réalisme des Modèles Pluie-Débit ? Ph.D. Thesis, Université Pierre-et-Marie-Curie, Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, C.; Michel, C.; Andréassian, V. Improvement of a parsimonious model for streamflow simulation. J. Hydrol. 2003, 279, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Castro, E.; Mendoza, P.A.; Vásquez, N.; Vargas, X. Exploring parameter (dis)agreement due to calibration metric selection in conceptual rainfall–runoff models. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2023, 68, 1754–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, J.; Sutcliffe, J. River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I—A discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 1970, 10, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrucca, L. GA: A Package for Genetic Algorithms in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2013, 53, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwat, N.; Kumar, R.; Qureshi, M.; Nagisetty, R.M.; Zhou, X. The Status, Applications, and Modifications of the Snowmelt Runoff Model (SRM): A Comprehensive Review. Hydrology 2025, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coron, L.; Thirel, G.; Delaigue, O.; Perrin, C.; Andréassian, V. The suite of lumped GR hydrological models in an R package. Environ. Model. Softw. 2017, 94, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, A.; Muñoz Carpena, R. Performance evaluation of hydrological models: Statistical significance for reducing subjectivity in goodness-of-fit assessments. J. Hydrol. 2013, 480, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, P.; Boyle, D.P.; Bäse, F. Comparison of different efficiency criteria for hydrological model assessment. Adv. Geosci. 2005, 5, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.V.; Sorooshian, S.; Yapo, P.O. Status of Automatic Calibration for Hydrologic Models: Comparison with Multilevel Expert Calibration. J. Hydrol. Eng. 1999, 4, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.V.; Kling, H.; Yilmaz, K.K.; Martinez, G.F. Decomposition of the mean squared error and NSE performance criteria: Implications for improving hydrological modelling. J. Hydrol. 2009, 377, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiemig, V.; Rojas, R.; Zambrano-Bigiarini, M.; De Roo, A. Hydrological evaluation of satellite-based rainfall estimates over the Volta and Baro-Akobo Basin. J. Hydrol. 2013, 499, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudin, L.; Andréassian, V.; Mathevet, T.; Perrin, C.; Michel, C. Dynamic averaging of rainfall-runoff model simulations from complementary model parameterizations. Water Resour. Res. 2006, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizukami, N.; Rakovec, O.; Newman, A.J.; Clark, M.P.; Wood, A.W.; Gupta, H.V.; Kumar, R. On the choice of calibration metrics for “high-flow” estimation using hydrologic models. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 2601–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriasi, D.N.; Arnold, J.G.; Liew, M.W.V.; Bingner, R.L.; Harmel, R.D.; Veith, T.L. Model Evaluation Guidelines for Systematic Quantification of Accuracy in Watershed Simulations. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbia, S.S.; Smullen, T.; Gill, L.; Johnston, P.; Pilla, F. Spatially distributed potential evapotranspiration modeling and climate projections. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 633, 571–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Sung, J.H.; Seo, Y.H.; Kim, B.S. Applicability of the daily hydrological models (GR4J, GR5J, and GR6J) in the South Korean basins. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sezen, C.; Bezak, N.; Šraj, M. Hydrological modelling of the karst Ljubljanica River catchment using lumped conceptual model. Acta Hydrotech. 2018, 31, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, B.K.; Chevallier, P.; Andréassian, V.; Tahir, A.A.; Arnaud, Y.; Neppel, L.; Bajracharya, O.R.; Budhathoki, K.P. Comparison of two snowmelt modelling approaches in the Dudh Koshi basin (eastern Himalayas, Nepal). Hydrol. Sci. J. 2014, 59, 1507–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calizaya, E.; Mejía, A.; Barboza, E.; Calizaya, F.; Corroto, F.; Salas, R.; Vásquez, H.; Turpo, E. Modelling Snowmelt Runoff from Tropical Andean Glaciers under Climate Change Scenarios in the Santa River Sub-Basin (Peru). Water 2021, 13, 3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, N.; Rodríguez, R.; Alzamora, R.; Gavilán, E.; Acuña, E.; Balocchi, F. Comparison of three daily rainfall-runoff models with multiple regression analysis for catchment parameters in Biobío, Chile. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SRM | ||

|---|---|---|

| Metric | Calibration | Validation |

| () | ||

| SRM | ||

|---|---|---|

| Metric | Calibration | Validation |

| () | ||

| Basin | PET Model | CemaNeige | GR4J | GR5J | GR6J |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aconcagua River at the Chacabuquito station | C | No | |||

| Yes | 0.119 | 0.005 | 0.006 | ||

| No | 0.074 | 0.005 | 0.004 | ||

| Yes | 0.074 | 0.005 | 0.004 | ||

| No | −0.022 | 0.005 | 0.003 | ||

| Yes | −0.021 | 0.005 | 0.003 | ||

| No | −0.022 | 0.005 | 0.003 | ||

| Yes | −0.039 | 0.005 | 0.003 | ||

| No | −0.43 | 0.005 | 0.003 | ||

| Yes | −0.022 | 0.005 | 0.003 | ||

| Duqueco River at the Cerrillos station | C | No | 0.826 | 0.819 | 0.829 |

| Yes | 0.845 | 0.853 | 0.851 | ||

| No | 0.834 | 0.832 | 0.835 | ||

| Yes | 0.854 | 0.860 | 0.853 | ||

| No | 0.807 | 0.751 | 0.810 | ||

| Yes | 0.831 | 0.796 | 0.840 | ||

| No | 0.810 | 0.744 | 0.810 | ||

| Yes | 0.835 | 0.789 | 0.839 | ||

| No | 0.811 | 0.771 | 0.820 | ||

| Yes | 0.836 | 0.814 | 0.844 |

| CemaNeige | Metric | GR4J | GR5J | GR6J | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calib. | Valid. | Calib. | Valid. | Calib. | Valid. | ||

| Without | 0.112 | −0.052 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.005 | −0.002 | |

| () | 14.362 | 14.833 | 15.203 | 14.467 | 15.200 | 14.474 | |

| 0.134 | 0.031 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.007 | ||

| −1.902 | 8.196 | 0.076 | 3.301 | −0.295 | 3.904 | ||

| −0.007 | 0.003 | −0.309 | −0.359 | −0.275 | −0.242 | ||

| 10.977 | 10.971 | 11.566 | 10.367 | 11.575 | 10.493 | ||

| 0.025 | −0.065 | −0.127 | −0.158 | −0.113 | −0.134 | ||

| 0.651 | 0.464 | 0.647 | 0.496 | 0.615 | 0.383 | ||

| With | 0.119 | −0.028 | 0.005 | −0.002 | 0.006 | 0.001 | |

| () | 14.302 | 14.663 | 15.205 | 14.470 | 15.192 | 14.450 | |

| 0.140 | 0.038 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.008 | ||

| −1.057 | 8.244 | −0.160 | 3.136 | −0.297 | 3.701 | ||

| 0.008 | 0.011 | −0.323 | −0.399 | −0.271 | −0.244 | ||

| 10.998 | 10.861 | 11.596 | 10.353 | 11.568 | 10.463 | ||

| 0.027 | −0.053 | −0.130 | −0.161 | −0.111 | −0.131 | ||

| 0.644 | 0.463 | 0.658 | 0.510 | 0.616 | 0.394 | ||

| CemaNeige | Metric | GR4J | GR5J | GR6J | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calib. | Valid. | Calib. | Valid. | Calib. | Valid. | ||

| Without | 0.834 | 0.837 | 0.832 | 0.840 | 0.835 | 0.846 | |

| () | 26.568 | 20.238 | 26.704 | 20.019 | 26.528 | 19.673 | |

| 0.834 | 0.865 | 0.834 | 0.861 | 0.838 | 0.862 | ||

| −0.441 | 5.801 | 1.160 | 5.999 | 1.096 | 4.802 | ||

| 0.864 | 0.873 | 0.844 | 0.888 | 0.837 | 0.902 | ||

| 13.931 | 11.864 | 14.087 | 11.605 | 14.064 | 11.366 | ||

| 0.860 | 0.807 | 0.872 | 0.848 | 0.853 | 0.854 | ||

| 0.304 | 0.182 | 0.297 | 0.169 | 0.304 | 0.177 | ||

| With | 0.854 | 0.844 | 0.860 | 0.865 | 0.853 | 0.855 | |

| () | 24.921 | 19.748 | 24.446 | 18.372 | 25.013 | 19.092 | |

| 0.854 | 0.862 | 0.861 | 0.872 | 0.853 | 0.871 | ||

| −1.165 | 3.705 | 0.412 | 2.612 | 1.070 | 3.060 | ||

| 0.882 | 0.901 | 0.868 | 0.928 | 0.876 | 0.906 | ||

| 14.001 | 11.638 | 13.366 | 11.175 | 13.538 | 11.065 | ||

| 0.827 | 0.777 | 0.859 | 0.864 | 0.863 | 0.865 | ||

| 0.290 | 0.149 | 0.289 | 0.187 | 0.265 | 0.166 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rivas, B.; Osores, V.; González, D.; Gualtieri, C.; Yépez, S. Performance Evaluation of the SRM and GRxJ—CemaNeige Models for Daily Streamflow Simulation in Two Catchments with Snow and Rain Dominated Hydrological Regimes. Water 2025, 17, 3413. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233413

Rivas B, Osores V, González D, Gualtieri C, Yépez S. Performance Evaluation of the SRM and GRxJ—CemaNeige Models for Daily Streamflow Simulation in Two Catchments with Snow and Rain Dominated Hydrological Regimes. Water. 2025; 17(23):3413. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233413

Chicago/Turabian StyleRivas, Bastián, Víctor Osores, David González, Carlo Gualtieri, and Santiago Yépez. 2025. "Performance Evaluation of the SRM and GRxJ—CemaNeige Models for Daily Streamflow Simulation in Two Catchments with Snow and Rain Dominated Hydrological Regimes" Water 17, no. 23: 3413. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233413

APA StyleRivas, B., Osores, V., González, D., Gualtieri, C., & Yépez, S. (2025). Performance Evaluation of the SRM and GRxJ—CemaNeige Models for Daily Streamflow Simulation in Two Catchments with Snow and Rain Dominated Hydrological Regimes. Water, 17(23), 3413. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233413