Spatiotemporal Changes in Grassland Yield and Driving Factors in the Kherlen River Basin (2000–2024): Insights from CASA Modeling and Geodetector Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data and Processing

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. CASA Model

2.3.2. Grassland Yield Estimation Model

2.3.3. Accuracy Validation

2.3.4. Trend Analysis

2.3.5. Geodetector Model

3. Results

3.1. Validation of Grassland Yield Estimation Results

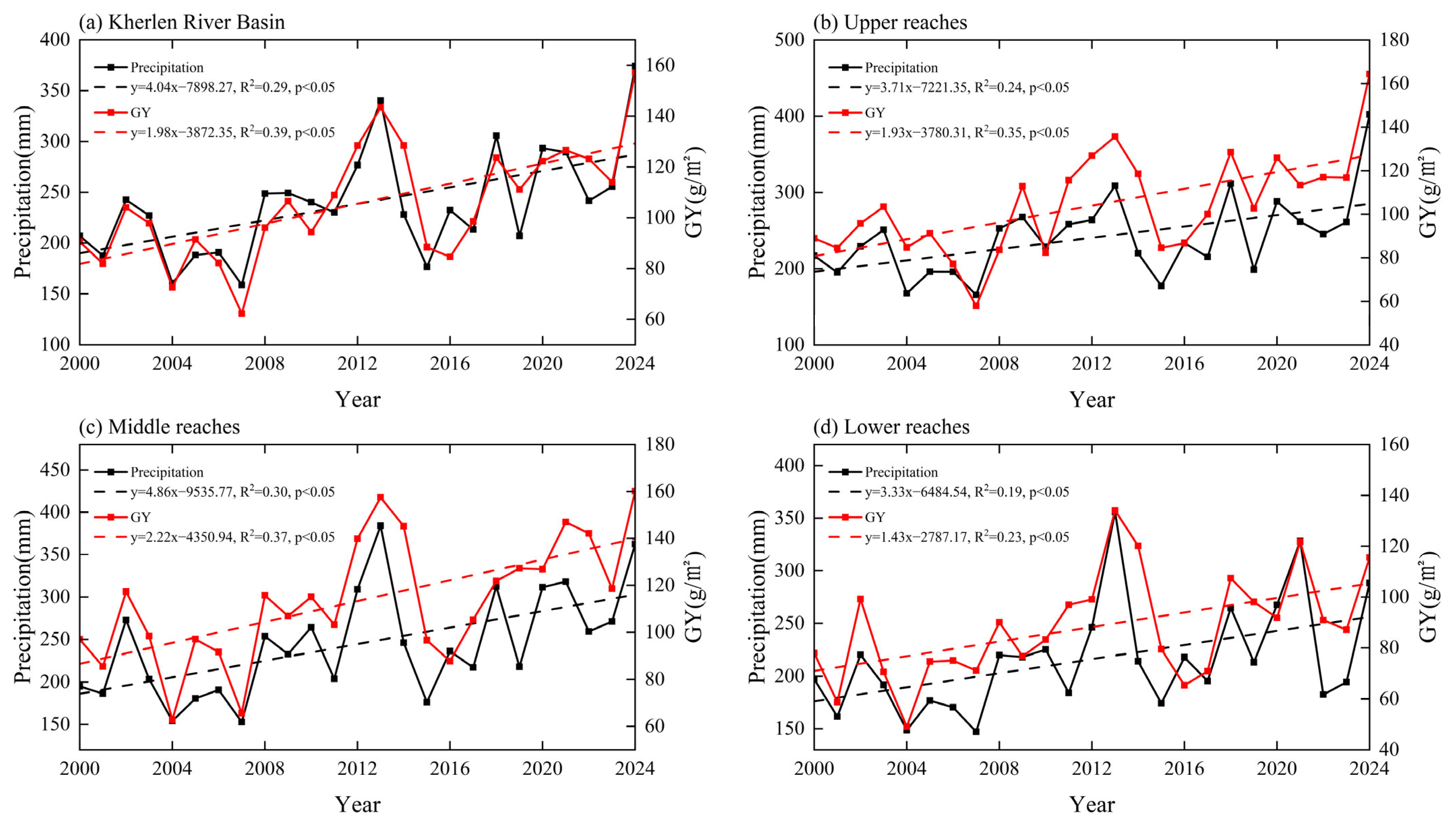

3.2. Temporal Change Characteristics of Grassland Yield

3.3. Spatial Changes in Grassland Yield

3.4. Driving Factors of Grassland Yield

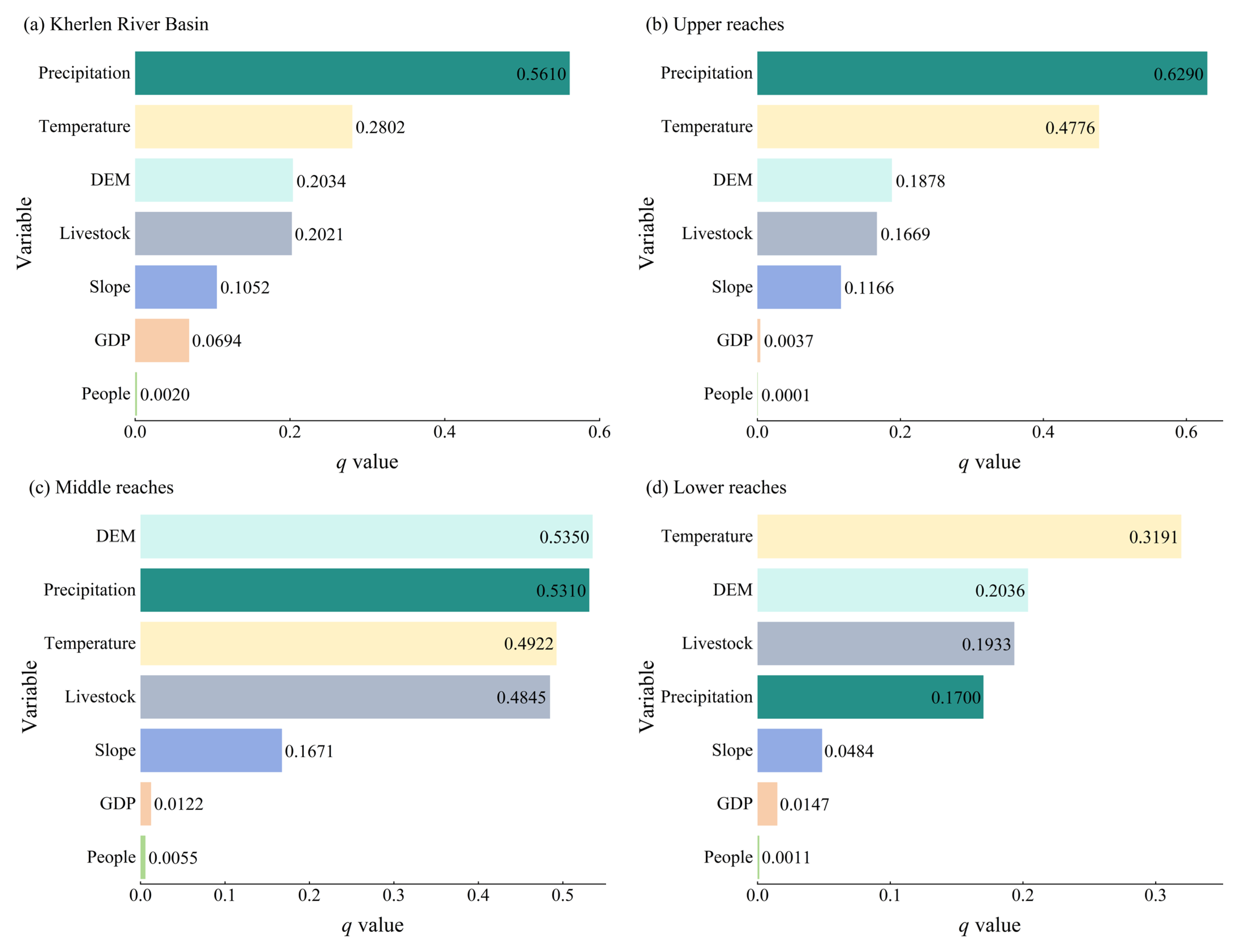

3.4.1. Single-Factor Impact Analysis of Grassland Yield

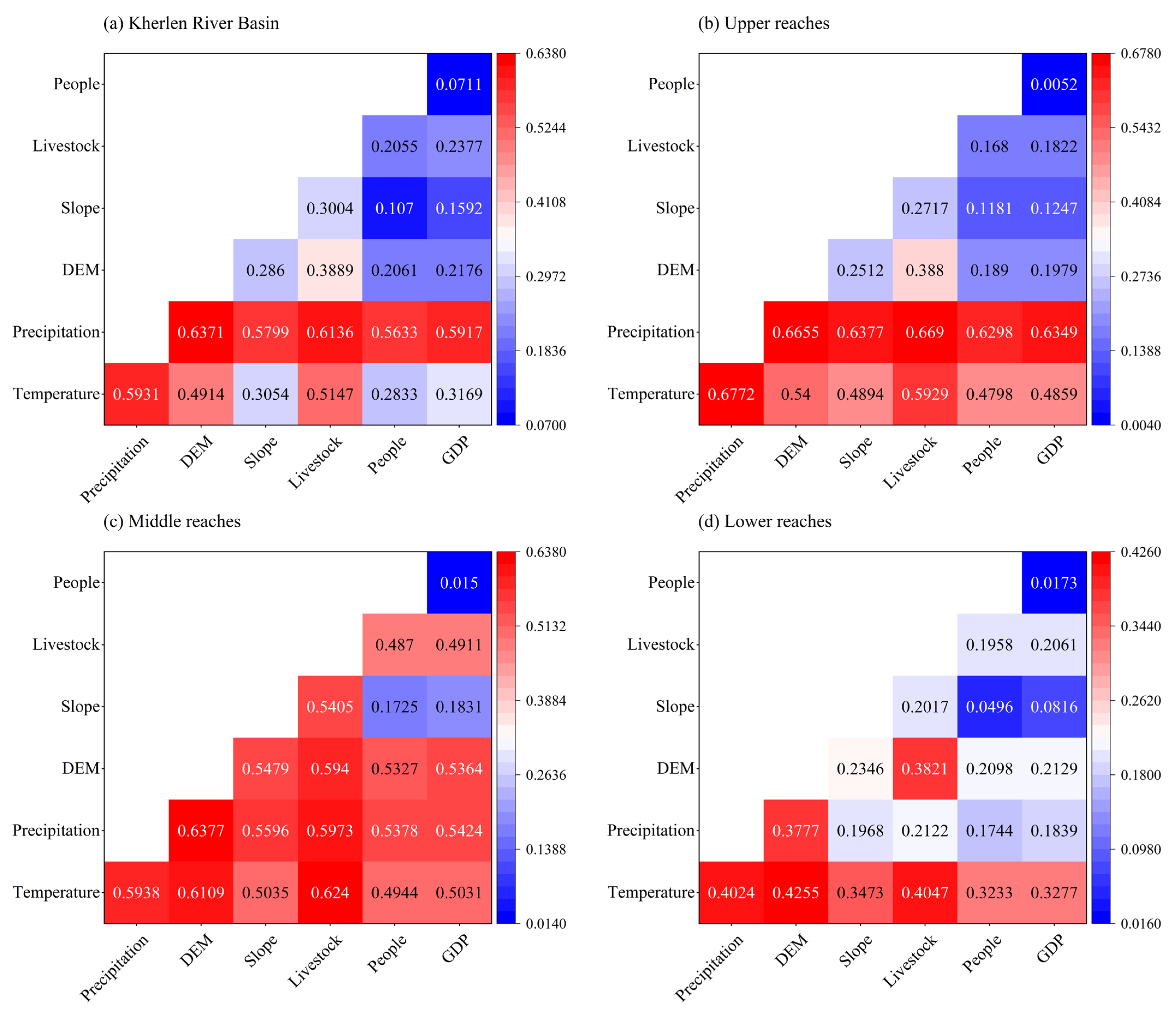

3.4.2. Interaction Analysis of Factors Influencing Grassland Yield

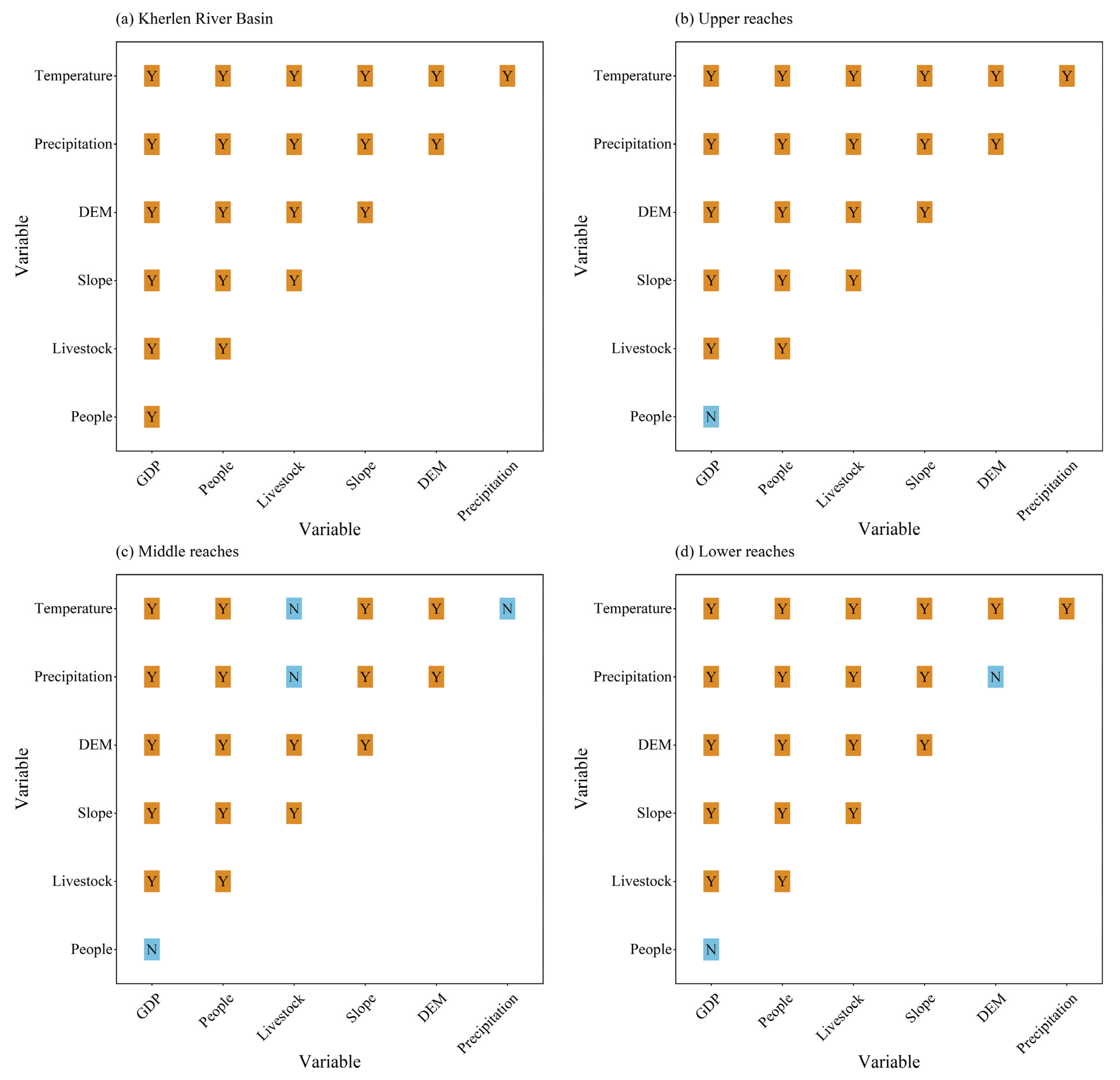

3.4.3. Ecological Detector Analysis of Factors Influencing Grassland Yield

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, M.; Shao, Q.; Ning, J.; Liu, G.; Liu, S.; Niu, L.; Zhang, X.; Huang, H. Analysis on ecological restoration in different ecogeographical divisions of the Tibetan Plateau. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2023, 31, 1211–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Liu, G.; Liu, A.; Bai, H.; Chao, L. Monitoring and driving force analysis of net primary productivity in native grassland: A case study in Xilingol steppe, China. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 31, 1233–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisavi, V.; Homayouni, S.; Yazdi, A.; Alimohammadi, A. Land cover mapping based on random forest classification of multitemporal spectral and thermal images. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Wan, Z.; Borjigin, S.; Zhang, D.; Yan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, R.; Gao, Q. Changing trends of NDVI and their responses to climatic variation in different types of grassland in Inner Mongolia from 1982 to 2011. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Jing, C.; Zhao, W.; Xu, Y. Grassland quality response to climate change in Xinjiang and predicted future trends. Acta Pratac. Sin. 2022, 31, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Okadera, T.; Nakayama, T.; Batkhishig, O.; Bayarsaikhan, U. Estimation of the carrying capacity and relative stocking density of Mongolian grasslands under various adaptation scenarios. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 913, 169772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, D.; Lu, Q.; Que, X.; Cheng, L.; Yang, Y.; Gao, P.; Cui, G. Evaluation of grassland ecosystem services in northern China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2024, 44, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umuhoza, J.; Jiapaer, G.; Yin, H.; Mind’je, R.; Gasirabo, A.; Nzabarinda, V.; Umwali, E. The analysis of grassland carrying capacity and its impact factors in typical mountain areas in Central Asia—A case of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 131, 108129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Ochir, A.; Togtokh, C.; Xu, C. Spatial-temporal pattern analysis of grassland yield in Mongolian Plateau based on artificial neural network. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Yang, X.; Jin, Y.; Wang, D.; Yang, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Yu, H.; Ma, H. Monitoring and evaluation of grassland-livestock balance in pastoral and semi-pastoral counties of China. Geogr. Res. 2012, 31, 1998–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinermann, S.; Asam, S.; Kuenzer, C. Remote sensing of grassland production and management—A review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Si, Y.; Schlerf, M.; Skidmore, A.; Shafique, M.; Iqbal, I. Estimation of grassland biomass and nitrogen using MERIS data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. 2012, 19, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisfelder, C.; Klein, I.; Bekkuliyeva, A.; Kuenzer, C.; Buchroithner, M.; Dech, S. Above-ground biomass estimation based on NPP time-series—A novel approach for biomass estimation in semi-arid Kazakhstan. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 72, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punalekar, S.; Verhoef, A.; Quaife, T.; Humphries, D.; Bermingham, L.; Reynolds, C. Application of Sentinel-2A data for pasture biomass monitoring using a physically based radiative transfer model. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 218, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Li, A.; Yin, G.; Nan, X.; Bian, J. Retrieval of grassland aboveground biomass through inversion of the PROSAIL model with MODIS imagery. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Han, X.; Liu, Y.; He, T.; Wu, Y. Estimation of net primary productivity in Inner Mongolia grassland based on optimized CASA model parameters. Inner Mong. For. Investig. Des. 2025, 48, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Chen, X.; Luo, M.; Meng, F.; Sa, C.; Bao, S.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, X.; Bao, Y. Quantifying the contribution of driving factors on distribution and change of net primary productivity of vegetation in the Mongolian Plateau. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, G.; Tuya, A.; Bayarsaikhan, S.; Dorjsuren, A.; Mandakh, U.; Bao, Y.; Li, C.; Vanchindorj, B. Variations and climate constraints of terrestrial net primary productivity over Mongolia. Quat. Int. 2020, 537, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Qin, P.; Yue, W.; Guo, Y.; Gao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yan, Z. High temporal and spatial estimation of grass yield by applying an improved Carnegie-Ames-Stanford approach (CASA)-NPP transformation method: A case study of Zhenglan Banner, Inner Mongolia, China. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 224, 109134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Zhu, W.; Wu, B.; Tuvdendorj, B.; Chang, S.; Mishigdorj, O.; Zhang, X. Assessment of the grassland carrying capacity for winter-spring period in Mongolia. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ma, C.; Yan, L. Analysis of climate change and its impact on grass yield of natural grassland in Henan County Qinghai Province from 1981 to 2022. Qinghai Pratac. 2023, 32, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Dai, Q.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Huang, W.; Xu, M.; Feng, Y. Identification of ecologically sensitive zones affected by climate change and anthropogenic activities in Southwest China through a NDVI-based spatial-temporal model. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, C. Geodetector: Principle and prospective. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Du, W.; Zhang, X.; Hong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hong, M.; Chen, S. Spatiotemporal changes in NDVI and its driving factors in the Kherlen River Basin. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Che, T.; Dai, L.; Jiang, Y. Comparative analysis on the spatiotemporal changes of vegetation and drivers in inland river basins of the Hexi Corridor, China. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 8112–8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Pei, H.; Jiang, J. The effect of temperature and precipitation during the growing season on the biomass of steppe communities in the Herlen Basin, northern China. Acta Pratac. Sin. 2012, 21, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Mao, D.; Yu, S.; Wang, Z.; Xiang, H. Temporal and spatial changes of grassland in Kherlen River Basin from 1980 to 2020. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 42, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummu, M.; Kosonen, M.; Sayyar, S. Downscaled gridded global dataset for gross domestic product (GDP) per capita PPP over 1990–2022. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lyu, J.; Li, Z.; Mu, W.; Wan, F. Spatiotemporal dynamics of vegetation NPP and its driving factors in Yiluo River Basin. J. North China Univ. Water Resour. Electr. Power (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 46, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Pan, Y.; Long, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Hu, H. Estimating net primary productivity of terrestrial vegetation based on GIS and RS: A case study in Inner Mongolia, China. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 2005, 9, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, J. Estimation of net primary productivity of Chinese terrestrial vegetation based on remote sensing. Chin. J. Plant. Ecol. 2007, 31, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. The potential evapotranspiration (PE) index for vegetation and vegetation-climatic classification (1)—An introduction of main methods and PEP program. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 1989, 13, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zhang, F.; Feng, Q.; Ma, X. Changes in grassland yield and grassland-livestock balance in Ordos City over the past 20 years. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2024, 44, 10887–10896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Kong, L.; Zhang, L.; Ouyang, Z.; Hu, J. The definition, methods and key issues of grassland ecosystem carrying capacity. Chin. J. Eco Agric. 2022, 30, 1228–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, X. Consistency and asymptotic distribution of the Theil–Sen estimator. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2008, 138, 1836–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Xue, X.; Wang, H.; Xu, W.; Sheng, Z.; Wang, Y. Changes in terrestrial water storage and its drivers on the north slope of Kunlun Mountains. Arid Land Geogr. 2024, 47, 1292–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Tian, P.; Wang, Z.; Shen, X. Spatio-temporal evolution of habitat quality in the East China Sea continental coastal zone based on land use changes. Acta. Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wei, W.; Shi, P.; Zhou, L.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Pang, S.; Xie, B. Spatiotemporal changes of land desertification sensitivity in the arid region of Northwest China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2020, 75, 1949–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Guan, Q.; Wang, Q.; Yang, L.; Pan, N.; Ma, Y.; Luo, H. Quantitative assessment of the impact of climatic factors on phenological changes in the Qilian Mountains, China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 499, 119594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wei, H.; Ochir, A.; Davaasuren, D.; Chonokhuu, S. Study on estimation method of Mongolia grassland production based on sparse samples. J. Geo Inf. Sci. 2020, 22, 1814–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Wu, X.; Tsunekawa, A.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Y.; Peng, L.; Chen, J.; Bai, K. Increasing precipitation promoted vegetation growth in the Mongolian Plateau during 2001–2018. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1153601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Tuya, W.; Qinchaoketu, S.; Nanzad, L.; Yong, M.; Kesi, T.; Sun, C. Climate change characteristics of typical grassland in the Mongolian Plateau from 1978 to 2020. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, S.; Li, P.; Huang, J.; Wang, J.; Ochir, A.; Yang, M.; Wang, T.; Chan, F. Spatiotemporal variability in drivers of grassland degradation and recovery under economic transformation in Mongolia. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 393, 127097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Deng, W.; Rao, P. Spatiotemporal characteristics and natural forces of grassland NDVI changes in Qilian Mountains from a sub-basin perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 157, 111186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Data Period | Time Scale | Spatial Scale | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEM | — | — | 30 m | https://www.gscloud.cn |

| NDVI | 2000–2024 | 16d | 250 m | https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/ |

| Meteorological data (temperature, precipitation, total solar radiation) | 2000–2024 | monthly | 0.1° | https://www.copernicus.eu/en |

| Land-use | 2000–2024 | yearly | 500 m | https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/ |

| Livestock | 2000–2020 | — | — | http://tj.nmg.gov.cn/ and http://www.1212.mn/ |

| Human population (People) | 2000–2020 | yearly | 1 km | https://www.ornl.gov/ |

| Gross domestic product (GDP) | 2000–2020 | yearly | 9 km | https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-025-04487-x#Sec12 (accessed on 15 June 2025) [28] |

| Slope | — | — | 30 m | Extracted by DEM |

| Land-Use Category | NDVImax | NDVImin | SRmax | SRmin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evergreen needleleaf forest | 0.647 | 0.023 | 4.67 | 1.05 |

| Deciduous coniferous forest | 0.738 | 0.023 | 6.63 | 1.05 |

| Deciduous broadleaf woodland | 0.747 | 0.023 | 6.91 | 1.05 |

| Mixed forest | 0.676 | 0.023 | 5.17 | 1.05 |

| Sparse forest | 0.636 | 0.023 | 4.49 | 1.05 |

| Shrubland | 0.636 | 0.023 | 4.49 | 1.05 |

| Grassland | 0.634 | 0.023 | 4.46 | 1.05 |

| Wetland | 0.634 | 0.023 | 4.46 | 1.05 |

| Cropland | 0.634 | 0.023 | 4.46 | 1.05 |

| Urban area | 0.634 | 0.023 | 4.46 | 1.05 |

| Gravel land | 0.634 | 0.023 | 4.46 | 1.05 |

| Water body | 0.634 | 0.023 | 4.46 | 1.05 |

| Criteria for Judgment | Interaction Types |

|---|---|

| Nonlinear weakening | |

| Bi-factor enhancement | |

| Independence | |

| Uni-factor nonlinear weakening | |

| Nonlinear enhancement |

| Basin Extent | Factor Name | Original q-Value | Original p-Value | p-Bonferroni | p-Holm | p-Benjamini–Hochberg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Kherlen River Basin | Temperature | 0.4950 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) |

| Precipitation | 0.6494 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | |

| DEM | 0.3591 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | |

| Slope | 0.2436 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00(√) | 0.00 (√) | |

| Livestock | 0.1781 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | |

| People | 0.0012 | 0.89 | 1.00 (×) | 0.89 (×) | 0.89 (×) | |

| GDP | 0.0538 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | |

| Upper reaches of the Kherlen River | Temperature | 0.6552 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) |

| Precipitation | 0.7342 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | |

| DEM | 0.4381 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | |

| Slope | 0.2625 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | |

| Livestock | 0.1241 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | |

| People | 0.0013 | 1.00 | 1.00 (×) | 1.00 (×) | 1.00 (×) | |

| GDP | 0.0094 | 0.04 | 0.28 (×) | 0.08 (×) | 0.05 (√) | |

| Middle reaches of the Kherlen River | Temperature | 0.3556 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) |

| Precipitation | 0.3368 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | |

| DEM | 0.4121 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | |

| Slope | 0.1273 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | |

| Livestock | 0.3545 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | |

| People | 0.0061 | 1.00 | 1.00 (×) | 1.00 (×) | 1.00 (×) | |

| GDP | 0.0079 | 1.00 | 1.00 (×) | 1.00 (×) | 1.00 (×) | |

| Lower reaches of the Kherlen River | Temperature | 0.3223 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) |

| Precipitation | 0.1876 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | |

| DEM | 0.1905 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | |

| Slope | 0.0608 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | |

| Livestock | 0.2242 | 0.00 | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | 0.00 (√) | |

| People | 0.0049 | 1.00 | 1.00 (×) | 1.00 (×) | 1.00 (×) | |

| GDP | 0.0151 | 0.99 | 1.00 (×) | 1.00 (×) | 1.00 (×) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, M.; Yang, H.; Wang, T.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Shao, Y.; Li, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B. Spatiotemporal Changes in Grassland Yield and Driving Factors in the Kherlen River Basin (2000–2024): Insights from CASA Modeling and Geodetector Analysis. Water 2025, 17, 3397. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233397

Yang M, Yang H, Wang T, Li P, Wang J, Shao Y, Li T, Zhang J, Wang B. Spatiotemporal Changes in Grassland Yield and Driving Factors in the Kherlen River Basin (2000–2024): Insights from CASA Modeling and Geodetector Analysis. Water. 2025; 17(23):3397. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233397

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Meihuan, Haowei Yang, Tao Wang, Pengfei Li, Juanle Wang, Yating Shao, Ting Li, Jingru Zhang, and Bo Wang. 2025. "Spatiotemporal Changes in Grassland Yield and Driving Factors in the Kherlen River Basin (2000–2024): Insights from CASA Modeling and Geodetector Analysis" Water 17, no. 23: 3397. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233397

APA StyleYang, M., Yang, H., Wang, T., Li, P., Wang, J., Shao, Y., Li, T., Zhang, J., & Wang, B. (2025). Spatiotemporal Changes in Grassland Yield and Driving Factors in the Kherlen River Basin (2000–2024): Insights from CASA Modeling and Geodetector Analysis. Water, 17(23), 3397. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233397