Abstract

Groundwater and water supply systems are increasingly vulnerable to contamination, yet most assessments consider either hydrogeological or infrastructure risks. This study introduces the Total Integrated Network (TIN) approach, a framework designed to evaluate vulnerability comprehensively from source to tap. Field investigations were conducted in Varaždin County, Croatia, focusing on the Belski Dol spring, Briška reservoir, and PS Filipići. Hydrochemical analyses, stable isotope of water (δ18O, δ2H), tritium, noble gases, and radon concentrations were monitored and combined with system-level assessments. Results show that the Belski Dol spring exhibits high stability and low vulnerability, with a TIN index of approximately 25%, supported by long groundwater residence times and consistent water quality. PS Filipići displayed moderate vulnerability (35%), while the Briška reservoir showed the highest index (53%), linked to elevated radon and nitrate concentrations and infrastructure-related risks. These findings indicate that natural hydrogeological protection alone cannot ensure safe drinking water. The TIN approach highlights the importance of integrating aquifer conditions with distribution system performance to identify critical control points and prioritize interventions. This integrated methodology offers a more realistic basis for water safety management, supporting proactive measures to safeguard supply resilience and public health.

1. Introduction

Groundwater vulnerability refers to the intrinsic characteristics of the subsurface that determine the susceptibility of groundwater to contamination from human activities [1,2]. This concept evaluates how easily pollutants can reach groundwater, considering factors such as soil and subsoil permeability, depth to the water table, type of aquifer, recharge rate, and the presence of protective layers [3]. Groundwater vulnerability is commonly classified as intrinsic, based solely on natural factors or specific, which incorporates both natural features and particular contaminants [2,4].

Several methods have been developed to assess groundwater vulnerability, assisting in the protection of aquifers from contamination [5,6,7,8]. Among the most recognized index-based methods are DRASTIC, GOD, SI, and SINTACS, each varying in complexity, applicability, and type of data required [5,6,7,8].

The DRASTIC method, developed by Aller et al. in 1987 [5] for the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), assesses vulnerability using seven parameters: depth to groundwater, net recharge, aquifer media, soil media, topography (slope), impact of the unsaturated zone, and hydraulic conductivity. Each parameter in DRASTIC is assigned a weighted value reflecting its relative influence on groundwater vulnerability, making it adaptable to specific hydrogeological contexts [5]. Despite its wide acceptance and ease of use, DRASTIC has limitations, such as subjectivity in assigning ratings, parameter redundancy, and limited suitability for karst aquifers where lateral contaminant flow is significant [9]. Foster introduced the GOD method in 1987, designed explicitly for rapid vulnerability assessment in regions with limited hydrogeological data [6]. GOD simplifies vulnerability estimation using only three parameters: Groundwater occurrence (aquifer confinement), Overlying lithology, and Depth to groundwater. GOD’s strength is simplicity and suitability for large-scale assessments, yet it struggles to capture the variability in aquifer conditions adequately, especially where vulnerability differences are subtle [10]. The Susceptibility Index (SI) developed in Portugal by Ribeiro in 2000 modifies the DRASTIC framework, excluding certain parameters such as soil media and the unsaturated zone, while adding a land-use factor. The inclusion of land-use enhances SI’s ability to identify anthropogenic influences, such as agricultural pollution, notably improving its predictive accuracy for specific contaminants like nitrates [11]. Nevertheless, SI may overestimate vulnerability by neglecting dilution effects or the recycling processes of groundwater contamination [12]. The SINTACS method, proposed by Civita and De Maio in 2004, emerged from Italy as an enhancement of the DRASTIC approach specifically tailored for Mediterranean hydrogeological conditions [7]. Like DRASTIC, SINTACS uses seven parameters—depth to groundwater, effective infiltration, unsaturated zone characteristics, soil texture, aquifer media, hydraulic conductivity, and topographic slope. However, it offers more precise weightings to reflect specific hydrogeological scenarios. SINTACS’s flexibility allows it to better account for localized hydrogeological differences, thus providing reliable vulnerability mapping, especially in porous aquifer systems.

Comparative studies have shown that the GOD method frequently produces oversimplified results compared to DRASTIC or SI, particularly when examining areas with moderate vulnerability variations [10,11]. Meanwhile, the SI method generally demonstrates stronger correlations with actual groundwater contamination data such as nitrate concentrations, making it particularly suitable for agricultural contexts [11,12]. Similarly, SINTACS has been successfully validated in various Mediterranean regions, effectively reflecting observed contamination patterns due to its locally adaptive weighting scheme [7]. Validation of vulnerability mapping typically involves comparing mapped vulnerability classes with observed groundwater quality parameters, emphasizing the practical importance of accurate parameter weighting and selection [13,14]. Nonetheless, the effectiveness of all these methods largely depends on data availability, appropriate parameter selection, and the extent to which local hydrogeological variability is accurately represented [15]. Overall, integrating or comparing multiple methods such as DRASTIC, GOD, SI, and SINTACS is recommended to enhance the reliability of groundwater vulnerability assessments and thus better inform policy decisions for aquifer protection [7,10,12,14].

Water supply system (WSS) vulnerability encompasses the susceptibility of the water infrastructure and its operation to various hazards that could compromise water quality and the continuity of supply [16,17]. These hazards may include physical infrastructure failures, contamination events, cyber-attacks, natural disasters, and operational shortcomings [18]. Assessing the vulnerability of WSS involves identifying weaknesses in their infrastructure, operations, or management that may lead to contamination, interruption, or degradation of water quality [19]. Several methodologies are employed for this purpose, each suited to specific contexts and data availability.

The All-Hazards Approach, promoted notably in the Technical Guide TG-374 of the United States Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine, evaluates risks from various potential threats (natural disasters, sabotage, accidents) by systematically assessing different WSS components such as sources, treatment plants, storage facilities, and distribution networks [20]. Another common method involves the use of Index-Based or Multi-Indicator Approaches, which combine various indicators, hydraulic, environmental, structural, and socio-economic to quantify vulnerability levels through weighted scoring [9]. These indicators are typically visualized spatially with GIS tools, providing practical and accessible results for decision-makers [10]. The Process-Based Simulation Approach employs hydraulic modeling software like EPANET to simulate contamination scenarios, system pressure changes, or pipe failures, providing detailed insights into WSS behavior under stress conditions [21]. This approach offers detailed predictive capability but requires extensive and accurate system data. Additionally, Complex Network Theory evaluates water systems as spatial networks. It identifies critical components, such as bottlenecks or essential connections, through network metrics like node connectivity and redundancy [22]. This method effectively highlights structural vulnerabilities but often overlooks aspects like water quality or contamination propagation. The Fuzzy Fault-Tree Analysis method addresses uncertainties inherent in data-limited systems. It uses a hierarchical structure to model failure probabilities and system vulnerabilities, allowing planners to prioritize mitigation measures effectively despite uncertainty [23]. The Risk-Based Asset Assessment framework is a traditional risk management approach widely adopted by utilities. It evaluates assets based on identified threats, vulnerability levels, and potential consequences of failure, providing clear prioritization for mitigation and resource allocation [19]. Governance and policy-oriented frameworks, such as the Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DPSIR) model and Water Safety Plans (WSP), integrate technical assessment with institutional and governance considerations, addressing socio-economic factors that influence overall system vulnerability [24]. Finally, specialized Climate Change Vulnerability Assessments explicitly evaluate WSS vulnerability related to climate risks, such as droughts, floods, and extreme events. Scenario-based modeling assesses system resilience under different climate conditions, informing adaptive strategies for future planning [25].

Despite significant progress in groundwater and water supply system vulnerability assessments, no existing study has yet succeeded in jointly evaluating the sensitivity of both the aquifer (hydrogeological system) and the water supply system (WSS) using a unified set of parameters. Traditionally, vulnerability assessments have been conducted separately for these two components. Some focus on the aquifer itself, particularly its intrinsic vulnerability to surface contamination [5,6], while others target the water supply infrastructure, such as source works, pipelines, reservoirs, and treatment plants, often using risk or failure analysis frameworks [19,23]. In groundwater vulnerability studies, methods like DRASTIC, GOD, and SI typically emphasize aquifer scale conditions, evaluating sensitivity on a catchment level or source protection area, rather than at the level of individual abstraction points [5,8]. This presents a critical gap: such approaches implicitly assume homogeneity of risk within the same aquifer, disregarding the local-scale heterogeneity that strongly influences the actual vulnerability of a specific spring or well [10,13]. In reality, hydrogeological heterogeneity, such as variations in permeability, porosity, structural features, and unsaturated zone thickness means that two wells located in the same aquifer can exhibit vastly different vulnerability levels. A recharge zone may protect one well due to thick low-permeability overburden, while another well nearby may be highly exposed due to thin or fractured cover layers [7,9]. Moreover, water supply system vulnerability assessments often begin downstream of the abstraction point, assuming the water source is adequately protected or uniformly vulnerable. This neglects source specific risk, which can critically impact overall WSS resilience. There is thus a pressing need for integrated methodologies that evaluate the combined vulnerability of the source aquifer unit and the water abstraction infrastructure using harmonized parameters such as recharge, land-use, geological media, well construction details, and system redundancy [12,25].

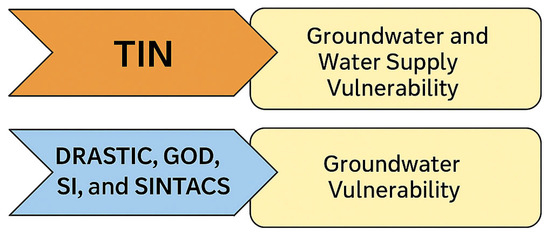

An integrated approach would bridge hydrogeological and WSS assessments and could support more precise risk-based zoning, resource allocation, and emergency planning, especially in complex or fractured aquifers where uniform vulnerability assumptions are misleading. The literature increasingly emphasizes this need for convergence, yet a comprehensive framework is still lacking [15,22]. This study introduces the Total Integrated Network (TIN) vulnerability approach, a comprehensive methodology for evaluating water quality risks along the entire source-to-tap pathway. In contrast to established methods such as DRASTIC, GOD, SI, and SINTACS, which focus solely on groundwater vulnerability, the TIN integrates both aquifer and water supply system vulnerabilities into a unified assessment (Figure 1). The TIN approach is designed to address both natural and anthropogenic factors that influence water vulnerability along the source-to-tap pathway. By integrating aquifer sensitivity with infrastructure and operational vulnerabilities, the TIN provides a more realistic and location specific understanding of risk. This enables utilities and decision-makers to prioritize interventions, allocate resources more efficiently, and implement targeted protection and monitoring strategies. Ultimately, the TIN supports proactive and adaptive water supply management, enhancing system resilience and safeguarding public health.

Figure 1.

Conceptual comparison between traditional groundwater vulnerability methods and the Total Integrated Network (TIN) approach.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

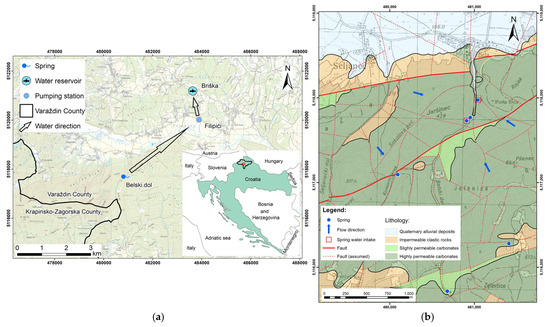

The study area is situated in the Varaždin County in northwestern Croatia, where potable water is distributed by public water supplier Varkom Inc. (Figure 2). The Belski Dol spring is located within Varaždin County, between the settlements of Podrute and Bela. It lies on the southeastern slopes of Mount Ivanščica, approximately 750 m from Bela and about 3 km from Podrute. The spring area sits at an elevation of approximately 230 m above sea level and is adjacent to the Belski stream and county road ŽC 2107. The spring comprises two main sources, the Upper and Lower springs which are about 350 m apart. The Upper spring is situated on the left side of the road (looking toward Bela), separated by the Belski stream, while the Lower spring lies to the right of the road, bordered by a stormwater drainage channel. The surrounding landscape is marked by a combination of forested hills and karst valleys, which are representative of the Ivanščica massif’s dynamic topography.

Figure 2.

Position map of the study area: (a) studied system with marked sampling points; (b) hydrogeological map of the Belski Dol spring catchment.

The geological composition of the Belski Dol catchment is diverse, reflecting the broader stratigraphic characteristics of the Ivanščica region. The terrain consists predominantly of Mesozoic and Cenozoic sedimentary rocks. Notably, four main lithological groups are present: (i) highly permeable carbonate rocks: dolomites, dolomitic limestones, and limestones. (ii) slightly permeable carbonate rocks: siliceous dolomites, cherty limestones, thin-bedded limestones, and flysch with chert and sandstone intercalations. (iii) impermeable clastic rocks: including sandstones, shales, marls, conglomerates, and clays. (iv) Quaternary alluvial deposits: composed of sands, gravels, silts, and clays of variable grain size and permeability (Figure 2) [26].

These formations reflect the region’s tectonic complexity, with numerous faults and fractures that contribute to groundwater movement. Breccia formations in the area, consisting of shallow-water carbonate clasts in deeper pelagic matrices, further indicate a complex depositional history.

The Belski Dol spring system is part of the Ivanščica fractured/fissured karst aquifer. The Upper spring was originally captured in 1972 for the village of Završje, with a measured discharge of approximately 5 L/s and an overflow of around 36 L/s. Since 1992, the Upper spring supplies about 28 L/s to the water network. It is enclosed by a 10 × 8 m fenced area. The Lower spring was integrated into the supply system in 1992 and features a non-concentrated capture system. It collects water from an alluvial fan using perforated Ø400 mm pipes laid in a 20 m stretch. Its yield is around 38 L/s. Together, the two springs provide approximately 63 L/s. Subsurface water travels from the Lower spring to a collection chamber through a gravity-fed closed pipeline, which also receives water from the Upper spring. From there, it is routed by gravity to the Filipići pumping station (PS) after which is pumped up to the Briška reservoir (R). From the reservoir, water is distributed by gravity through a pipeline to consumers.

2.2. Water Analyses

2.2.1. Physico-Chemical Analysis

Field measurements of electrical conductivity (EC), water temperature (T) and pH, were performed using a calibrated portable WTW instrument from December 2021 till December 2023 monthly at the Belski Dol spring. At reservoir Briška and PS Filipići, sampling campaigns were carried out twice in 2022 and twice in 2023. Total alkalinity was determined on-site by titration with 1.6 N H2SO4, using phenolphthalein and bromocresol green–methyl red as indicators. Major cations and anions were analyzed using ion chromatography on a Dionex ICS-6000 DC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at the Hydrochemical Laboratory of the Croatian Geological Survey, with analytical precision assessed via the ionic balance error (IBE), calculated from ion concentrations expressed in meq/L and found to be within the acceptable limit of ±5%. The long-term dataset is part of water sampling campaigns conducted at spring, PS Filipići and reservoir Briška, as part of the operational monitoring by Varkom Inc.

2.2.2. Stable Water Isotope Analysis

The δ18O and δ2H values were determined using a Picarro L2130i analyzer (Santa Clara, CA, USA) at the Hydrochemical Laboratory of the Croatian Geological Survey. All measurements were calibrated against USGS standards (USGS48: −2.224 ± 0.012‰ for δ18O, −2.0 ± 0.4‰ for δ2H; USGS46a: −30.09 ± 0.05‰ for δ18O, −235.6 ± 0.7‰ for δ2H), which were periodically verified against International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) reference materials: Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water 2 (VSMOW2) and Standard Light Antarctic Precipitation 2 (SLAP2). Measurement precision was ±0.2‰ for δ18O and ±1‰ for δ2H. Instrument drift control, use of internal laboratory standards, and QA/QC procedures followed the protocol described in [27].

2.2.3. Noble Gas and Tritium Measurement

Water samples were taken into copper tubes equipped with stainless steel pinch-off clamps. During sampling, the pressure of the water was kept as high as dissolved gases could not release from the water. Samples were analyzed in the Isotoptech Zrt. Debrecen, Hungary, according to the method described in Papp et al., 2012 [28]. Measured data were interpreted by inverse modeling of noble gas concentrations [29,30,31].

2.2.4. Radon Analysis

Radon concentration in water was measured using the RAD8 radon detector, produced by DURRIDGE Company Inc. (Billerica, MA, USA). A 250 mL water sample was collected in a clean glass vial, taking care to avoid the presence of air bubbles in order to prevent radon loss. The vial was then securely sealed and connected to the RAD8 system using a closed-loop aeration setup. The radon concentration in the original water sample is then calculated using the measured air concentration and the established partition coefficient for radon between water and air. Results were corrected by using Capture 8 software [32].

2.3. Total Integrated Network Vulnerability Approach (TIN)

By tracing water and its quality changes from recharge zones, through abstraction and conveyance, storage, and distribution, the TIN approach identifies and quantifies cumulative and segment specific risks. This holistic methodology enables: spatial mapping of vulnerability hot spots across both the aquifer and WSS infrastructure; temporal assessment of changes in vulnerability due to natural processes (e.g., recharge variability) and operational factors (e.g., system maintenance, leakage); identification of critical control points (CCPs) where interventions can most effectively reduce overall risk.

The proposed approach utilizes 10 parameters, half of which are routinely monitored by all water supply companies in accordance with the obligations of the Drinking Water Directive (EU) 2020/2184 [33]. Table 1 and Table 2 provide an overview of the relevance of each parameter and what changes in their values can indicate within both the groundwater system and the water supply system (WSS).

Table 1.

Parameter indication in the groundwater system.

Table 2.

Parameter indication in the WSS.

Each parameter is assigned a set of quantitative criteria used to define a vulnerability score ranging from 1 (Very Low) to 5 (Very High) (Table 3). These scores contribute to the overall weighted vulnerability calculation. In practice, threshold values should be tailored to the specific system and dataset, but the following table provides a general scoring framework. For each parameter, the vulnerability score is based on the observed variability, expressed either as a percentage change from a baseline or Maximum Allowable Concentration (MAC) value, or as an absolute concentration difference, as shown in Table 3. However, these parameter fluctuations needed to be quantified, which was performed using the Z-score. The Z-score expresses how much each measured value deviates from the mean in units of standard deviation. This approach allows for a clear comparison of variability among different sampling sites.

Table 3.

Vulnerability scoring scale.

Once individual vulnerability scores are assigned to each parameter based on the criteria described above, the following calculation steps are applied to integrate them into the overall TIN method index:

- Each parameter is assigned a weighting factor reflecting its relative importance or diagnostic value in assessing system vulnerability. These weights can be uniform or adapted based on expert judgment, sensitivity analysis, or system-specific relevance.

- Since parameters are measured on different scales or units, normalization must be applied to ensure comparability.

Then the TIN vulnerability index is computed as a weighted average of all individual scores:

where n = total number of parameters included.

The final TIN Index value is expressed as a percentage, representing the proportion of the maximum possible vulnerability score. Based on this percentage, the system’s vulnerability is classified into three categories: values ranging from 0% to 30% indicate low vulnerability, values between 31% and 60% correspond to moderate vulnerability, while values from 61% to 100% reflect high vulnerability. This classification enables clear interpretation of results and supports risk-informed decision-making in groundwater and water supply system management.

3. Results and Discussion

In this chapter, the TIN method is applied to the Belski Dol spring and the part of the water supply system fed by this source to assess their vulnerability.

3.1. Hydrochemical Properties of Spring and WSS Waters

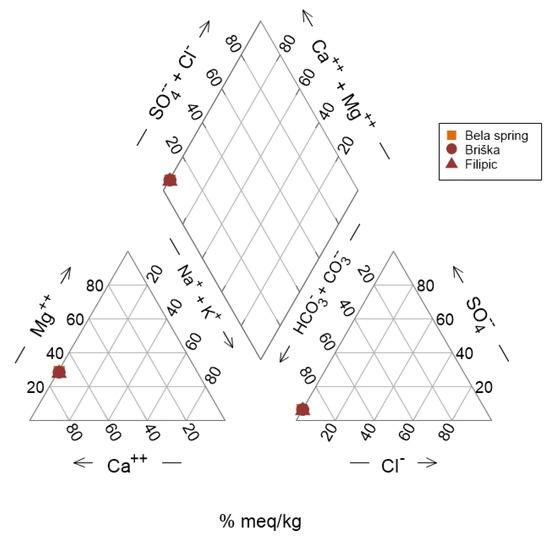

The Piper diagram shows that water samples from Belski Dol spring, the Briška reservoir, and the PS Filipići belong to the CaMg–HCO3 hydrochemical type (Figure 3). Calcium and bicarbonate are the dominant ions, indicating water rock interaction primarily with carbonate formations (dolomite and limestone). The similarity between all three samples suggests that there are no significant geochemical changes observed within the water supply network, indicating consistency in water quality from source to distribution points.

Figure 3.

Piper diagram of sampled waters.

The EC of the spring water ranges from 480 to 501 µS/cm, with an average of 494 µS/cm and with a standard deviation of 6.9 µS/cm (Table 4a). This low variation indicates that the mineralization of the water is stable over time. The water temperature is very constant as EC, between 11.0 and 11.3 °C, with an average of 11.2 °C and with a standard deviation of only 0.1 °C, which is within the measurement error. The pH values range from 7.05 to 7.61, with an average of 7.47 and a standard deviation of 0.13, showing that the water is consistently slightly alkaline without extreme changes that could occur due contamination breakthrough. All three parameters indicate that groundwater has long residence time.

Table 4.

(a) Statistical data of measured parameters (Croatian Geological Survey). (b) Statistical data of measured parameters (Varkom Inc.).

Bicarbonate concentrations vary between 295 and 380 mg/L, averaging 327 mg/L, with a standard deviation of 18 mg/L, again pointing out the stability of the groundwater system. In addition, chloride, nitrate and sulphate are showing the same (Table 4a). Chloride concentrations are very low, ranging from 0.117 to 3.2 mg/L, with an average of 1.8 mg/L and a standard deviation of 0.7 mg/L. Sulfate concentrations range from 9 to 14.4 mg/L, with an average of 11.1 mg/L and a standard deviation of 1.2 mg/L. The nitrate content ranges from 1.1 to 5.57 mg/L, with an average of 3.0 mg/L and a standard deviation of 1.0 mg/L. These values reflect low to moderate nitrate levels, always well below the MAC for the drinking water. Finally, ammonium and nitrite are consistently below detection limits (<0.01 mg/L), which confirms no reductive condition in the aquifer and the absence of recent contamination. Sodium concentrations are low, between 0.97 and 1.5 mg/L, with an average of 1.3 mg/L and with a standard deviation of 0.1 mg/L, while potassium values range from 0.3 to 0.8 mg/L, averaging 0.5 mg/L, with a standard deviation of 0.1 mg/L. Both cations show very limited variability, typical for natural groundwater without influence of waste water contamination, road salting, etc. Calcium concentrations vary between 58.6 and 72.3 mg/L, with an average of 63.4 mg/L and with a standard deviation of 3.0 mg/L, while magnesium concentrations vary from 22.9 to 36.6 mg/L, with an average of 27.5 mg/L and with a standard deviation of 2.5 mg/L. These two parameters together indicate a moderately hard water type with relatively stable composition. Moderate water hardness over time in the supply network may lead to chemical corrosion of pipes, clogging due to carbonate scaling, and ultimately a potential negative impact on the integrity of the distribution system [34,35].

The stable isotopes δ18O and δ2H also display narrow ranges: δ18O varies between −10.82 and −10.21‰, with an average of −10.5‰ and a standard deviation of 0.16‰, while δ2H ranges from −73.9 to −70.8‰, averaging −71.7‰ with a standard deviation of 0.76‰. In addition, values are lying close the local meteoric water line (LMWL) from Marković et al. [27], indicating precipitation origin. The standard deviations of both isotopes fall within the measurement error, which indicates a long residence time of the groundwater, consistent with the stability of EC, temperature, and pH values.

To support this theory, the recharge temperature was calculated based on noble gas measurements. These measurements provide an independent proxy for past recharge conditions, as dissolved noble gases in groundwater are sensitive to temperature at the time of infiltration. Thus, the noble gas derived recharge temperature serves as additional evidence for validating the interpretation of groundwater origin and residence time. The temperature derived from noble gas measurements is approximately 8 °C. This clearly indicates a higher recharge altitude, since in the lowlands the average temperature is 10.5 °C [27]. In addition, calculated MRT based upon 3H/3He is 25 years.

Considering that the Briška reservoir was sampled twice and the Filipići pumping station was sampled only once and analyzed in detail for the same parameters as for the spring (except for 3H/3He and noble gases), it was not possible to establish a trend from the available data. However, the results could be compared with the spring water. Statistical analysis was carried out using Varkom data, but only for the chemical parameters EC, temperature, pH, and NO3− (Table 4b).

As water moves away from the spring source at Bela toward the downstream sites of the PS Filipići and the Briška reservoir, a decrease in calcium and magnesium concentrations was observed (Table 5). This progressive reduction is not merely a dilution effect, but is closely linked to carbonate precipitation processes. As pH increases along the flow path, the water becomes supersaturated with respect to carbonate minerals, favoring the deposition of calcite and dolomite. The removal of Ca2+ and Mg2+ through mineral precipitation explains the observed decrease in concentrations downstream and over time.

Table 5.

Measured hydrochemical and isotopic parameters from source throughout WSS.

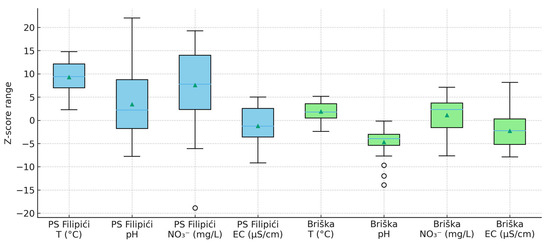

Looking at Figure 4, at PS Filipići, the distribution is noticeably wider across most parameters, particularly for pH and nitrate, which display strong positive and negative deviations from the mean. This suggests substantial temporal or local variability in chemical conditions. Temperature also shows a moderate spread, while EC exhibits both upward and downward fluctuations, pointing to instability in physical water properties as well. In contrast, Briška reservoir demonstrates generally narrower distributions, reflecting more stable water quality conditions. pH still shows a notable spread, but is significantly less variable than at Filipići. Nitrate and EC have moderate ranges, though their deviations remain confined within a tighter band. Temperature at Briška reservoir is the most stable parameter, with minimal variation in Z-scores.

Figure 4.

Distribution of monitored elements in the WSS waters. Note: The edges of the box mark the first and third quartiles, the whiskers show the minimum and maximum, a triangle represents the mean, and the central line indicates the median.

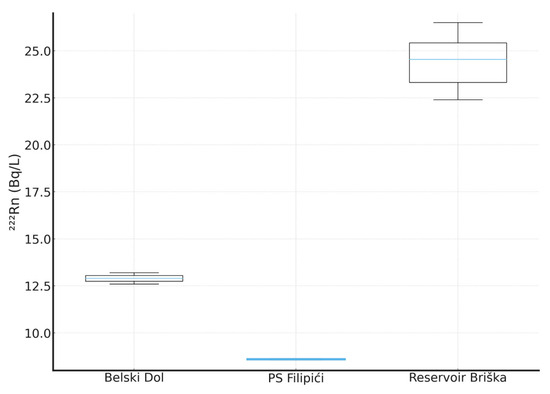

On the other hand, at Belski Dol spring, radon concentrations are relatively stable and tightly clustered between 12.6 and 13.3 Bq/L, indicating only minor variability over time (Figure 5). The Briška reservoir displays the highest concentrations, ranging from 22.4 to 26.3 Bq/L, with a wider spread compared to Belski Dol, suggesting more dynamic conditions or stronger radon inputs at this location. In contrast, PS Filipići shows the lowest radon level, with only a single recorded value of 8.7 Bq/L, representing the minimum observed concentration across all sites.

Figure 5.

Relationship between measured 222Rn concentration in the spring and throughout the WSS. Note: The edges of the box mark the first and third quartiles, the whiskers show the minimum and maximum, and the central line indicates the median.

The unusually high 222Rn concentration observed in the Briška reservoir compared to the source Belski Dol can be explained by the cumulative effects of soil-rock radon emanation coupled with aged distribution infrastructure. Belski Dol, being close to the source, exhibits relatively modest radon levels (12.6–13.3 Bq/L) and is less exposed to external contamination. However, at Briška reservoir, water travels through older pipelines and possibly through soils or fractured bedrock that allow radon to diffuse or emanate into the water column, which together with microleaks and pipe joint degradation may boost radon levels. Such phenomena were observed by Özden et al., demonstrating how soil properties such as porosity, moisture, and radium content strongly influence radon release from the ground [36]. In addition, Sukanya & Sabu outline how aquifer-rock contact and aged pathways (via fractures or disturbed soil) enhance radon concentration in downstream water [37]. Taken together, these findings provide a coherent explanation for the higher 222Rn levels observed in the Briška reservoir relative to the Belski Dol spring.

3.2. Vulnerability of the Spring Catchment and of WSS

In order to assess the TIN vulnerability of the study sites, a set of eight hydrochemical and isotopic parameters was selected for the WSS locations: Briška reservoir and PS Filipići. These parameters include EC, T, pH, NO3−, Cl−, the stable isotopes δ18O and δ2H, and 222Rn. For the source spring Belski Dol, the same eight parameters were considered, but the analysis was extended to include tritium and noble gases, as these provide additional information on groundwater residence time and recharge conditions. The interpretation of our results reflects the scope of the available dataset, and the limited sampling frequency for certain parameters is a factor in the baseline uncertainty.

The methodology followed the approach described in the TIN framework, in which each parameter is assigned a vulnerability score ranging from 1 (low) to 5 (high) presented in Table 3. The scoring was based on the degree of deviation from reference conditions. For the WSS locations, the reference baseline was the values measured at Belski Dol spring on the same sampling date, thus representing the natural source water quality. In contrast, for Belski Dol itself, the reference was defined as the mean of its own values over the monitoring period, so that the index reflects temporal variability of the spring rather than spatial differences. For most parameters, the score was assigned according to the percentage deviation from the baseline: values within ±10% correspond to a score of 1, deviations of 10–20% to a score of 2, 20–30% to 3, 30–50% to 4, and >50% to 5. In addition, regulatory thresholds were applied as overriding conditions: nitrate concentrations above 50 mg NO3−/L, pH values below 6.5 or above 9.5, and temperatures exceeding 25 °C automatically receive the highest score of 5. For stable isotopes, absolute differences relative to the baseline were used instead of percentages, with threshold bands defined in per mil (‰). The δ18O values received scores of 1 for differences <0.10‰, 2 for 0.10–0.20‰, 3 for 0.20–0.30‰, 4 for 0.30–0.50‰, and 5 for >0.50‰. For δ2H, the thresholds were set at 1, 2, 3, and 5‰ for scores 1 to 4, with values above 5‰ receiving a score of 5.

Once all parameters had been scored, the TIN vulnerability index for each site and date was calculated as the arithmetic mean of the scores, normalized to a percentage of the maximum possible value. For Belski Dol, an additional adjustment was applied to account for the evidence of long groundwater residence time provided by tritium and noble gas measurements, which indicate a mean residence time of about 25 years and recharge under cold climatic conditions. This information implies a higher degree of natural protection of the source.

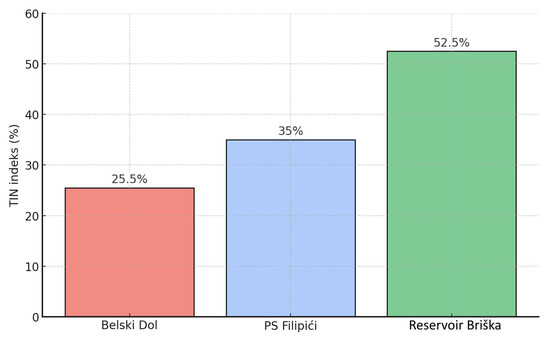

The results show that Belski Dol spring consistently exhibits the lowest TIN vulnerability, with an overall index of 25.5%, placing it in the category of low vulnerability. PS Filipići has a somewhat higher index of 35%, reflecting moderate deviations from the source conditions. The Briška reservoir displays the highest values, with an average index of 52.5%, corresponding to moderate vulnerability (Figure 6). This higher vulnerability is primarily associated with greater deviations in radon, nitrate, and conductivity compared to the Belski Dol baseline. Taken together, the analysis demonstrates that the natural spring Belski Dol is well protected and chemically stable, while the WSS sites show increased vulnerability, with Briška reservoir being the most affected.

Figure 6.

TIN vulnerability assessments results.

4. Conclusions

Our TIN concept advances traditional groundwater vulnerability assessments by explicitly considering the entire water delivery network, thus supporting more robust risk management and safeguarding of drinking water resources. Moving beyond conventional aquifer assessments to a holistic system perspective, this approach provides water managers with a practical framework for enhancing operational security.

The results showed that the Belski Dol spring is characterized by high hydrochemical stability, long residence times and overall low vulnerability, while also exhibiting a minimal diffuse nitrate risk, which further supports its role as a reliable and naturally well-protected drinking water source. On the other hand, the WSS part of the study area (Briška reservoir and PS Filipići) showed increased vulnerability due to deviations in parameters such as radon, nitrates, and electrical conductivity. The Briška reservoir exhibited the highest vulnerability index, indicating problems from PS Filipići in the form of aged pipelines and potential pathways for radon emanation, as well as for the future pollution.

The integrated evaluation confirmed that hydrogeological protection alone is not sufficient to ensure water safety. Instead, continuous monitoring across both natural and engineered components is essential. By incorporating hydrochemical, isotopic, and radiological parameters, the TIN method allowed identification of critical control points where interventions would be most effective, such as targeted monitoring at the Briška reservoir and maintenance of distribution infrastructure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.; methodology, T.M.; validation, T.M., formal analysis, T.M., N.N.-H. and L.P.; investigation, T.M. and I.K.; data curation, T.M. and N.N.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M.; writing—review and editing, N.N.-H., L.P. and I.K.; visualization, I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The presented research was conducted in the scope of the internal research project “NITROVERT” at the Croatian Geological Survey, funded by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan 2021–2026 of the European Union—NextGenerationEU, and monitored by the Ministry of Science, Education and Youth of the Republic of Croatia. It was also supported by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) through the Coordinated Research Project F31007.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Varaždin Utility Company (VARKOM) and Robert Rutić for their support during sampling campaigns.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCP | Critical Control Point |

| DPSIR | Drive-Pressure-State-Impact_Response Framework |

| DRASTIC | A Standardized System for Evaluating Ground Water Pollution Potential Using Hydrogeologic Settings |

| EC | Electrical Conductivity |

| EPA | The Environmental Protective Agency |

| EPANET | A modeling software of US EPA for modeling water distribution systems |

| GOD | A methodology for Evaluating Ground Water Vulnerability |

| IAEA | International Atomic Energy Agency |

| LMWL | Local Meteoric Water Line |

| MAC | Maximum Allowable Concentration |

| MRT | Mean Residence Time |

| PS | Pumping Station |

| R | Reservoir |

| SI | Susceptibility Index |

| SINTACS | A method developed in Italy for evaluating Ground Water Vulnerability |

| SLAP2 | Standard Light Antarctic Precipitation 2 |

| T | Temperature |

| TIN | Total Integrated Network Vulnerability Approach |

| USGS | The U.S. Geological Survey |

| VSMOW2 | Viena Standard Mean Ocean Water 2 |

| WSP | Water Safety Plan |

| WSS | Water Supply System |

References

- Vrba, J.; Zaporoz, A. Guidebook on Mapping Groundwater Vulnerability. In International Association of Hydrogeologists; Heise, H., Ed.; Springer: Hannover, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, S.; Hirata, R.; Gomes, D.; D’Elia, M.; Paris, M. Groundwater Quality Protection: A Guide for Water Utilities, Municipal Authorities and Environment Agencies; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, D.; Dassargues, A.; Drew, D.; Dunne, S.; Goldscheider, N.; Neale, I.; Popescu, I.; Zwahlen, F. Main concepts of the “European approach” to karst-groundwater-vulnerability assessment and mapping. Hydrogeol. J. 2002, 10, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, S.H.; Dixon, B.; Griffin, D. Assessing intrinsic and specific vulnerability models ability to indicate groundwater vulnerability to groups of similar pesticides: A comparative study. Phys. Geogr. 2018, 39, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aller, L.; Bennett, T.; Lehr, J.H.; Petty, R.J.; Hackett, G. Drastic: A Standardized System for Evaluating Ground Water Pollution Potential Using Hydrogeologic Settings; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1987; EPA/600/2-87/035. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, S.S.D. Fundamental concepts in aquifer vulnerability, pollution risk and protection strategy. In Vulnerability of Soil and Groundwater to Pollutants; Van Duijvenbooden, W., Van Waegeningh, H.G., Eds.; Committee on Hydrological Research: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1987; pp. 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Civita, M.; De Maio, M. Assessing and mapping groundwater vulnerability to contamination: The Italian ‘Combined’ approach. Geofís. Int. 2004, 43, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L. SI: A New Index of Aquifer Susceptibility to Agricultural Pollution; Instituto Superior Técnico: Lisbon, Portugal, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gogu, R.C.; Dassargues, A. Current trends and future challenges in groundwater vulnerability assessment using overlay and index methods. Environ. Geol. 2000, 39, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakis, N.; Voudouris, K. Comparison of three applied methods of groundwater vulnerability mapping. In Advances in the Research of Aquatic Environment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hamza, M.H.; Maâlej, A.; Ajmi, M.; Added, A. Validity of the vulnerability methods DRASTIC and SI applied by GIS technique to the study of diffuse agricultural pollution in two phreatic aquifers of a semi-arid region (Northeast of Tunisia). AQUAmundi 2010, Am01009, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anane, M.; Abidi, B.; Lachaal, F.; Limam, A.; Jellali, S. GIS-based DRASTIC, Pesticide DRASTIC and the Susceptibility Index (SI): Comparative study for evaluation of pollution potential in the Nabeul-Hammamet shallow aquifer, Tunisia. Hydrogeol. J. 2013, 21, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazavi, R.; Ebrahimi, Z. Assessing groundwater vulnerability to contamination in an arid environment using DRASTIC and GOD models. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 12, 2909–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghouili, N.; Jarraya-Horriche, F.; Hamzaoui-Azaza, F.; Zaghrarni, M.F.; Ribeiro, L.; Zammouri, M. Groundwater vulnerability mapping using the susceptibility index (SI) method: Case study of Takelsa Aquifer, Northeastern Tunisia. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2021, 173, 104035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, D.; Haritash, A.K.; Singh, S.K. A comprehensive review of groundwater vulnerability assessment using index-based, modelling, and coupling methods. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 296, 113161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA. Vulnerability Assessment Factsheet; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, R.; Uber, J.G.; Janke, R. Modeling, sensitivity, and uncertainty analysis for contamination warning system design in water distribution systems. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2010, 136, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lence, B.J.; Maier, H.R.; Tolson, B.A.; Foschi, R.O. First-order reliability method for estimating reliability, vulnerability, and resilience. Water Resour. Res. 2001, 37, 779–790. [Google Scholar]

- ASCE. Guidelines for Physical Security of Water Utilities; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- USACHPPM. Technical Guide 374: Water System Vulnerability Assessment; United States Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine: Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rossman, L.A. EPANET 2 Users Manual; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yazdani, A.; Jeffrey, P. Complex network analysis of water distribution systems. Chaos 2011, 21, 016111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedzadeh, S.; Roozbahani, A.; Heidari, A. Risk Assessment of Water Resources Development Plans Using Fuzzy Fault Tree Analysis. Water Resour Manag. 2020, 34, 2549–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Environmental Indicators: Development, Measurement, and Use; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA. Climate Resilience Evaluation and Awareness Tool Exercise with North Hudson Sewerage Authority and New York-New Jersey Harbor & Estuary Program; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- RGN. Study on the Protection Zones of the Belski Dol Spring; Faculty of Mining, Geology and Petroleum: Zagreb, Croatia, 2008. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Marković, T.; Karlović, I.; Perčec Tadić, M.; Larva, O. Application of Stable Water Isotopes to Improve Conceptual Model of Alluvial Aquifer in the Varaždin Area. Water 2020, 12, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, L.; Palcsu, L.; Major, Z.; Rinyu, L.; Tóth, I. A mass spectrometric line for tritium analysis of water and noble gas measurements from different water amounts in the range of microliters and milliliters. Isot. Environ. Health Stud. 2012, 48, 494–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeschbach-Hertig, W.; Peeters, F.; Beyerle, U.; Kipfer, R. Interpretation of dissolved atmospheric noble gases in natural waters. Water Resour. Res. 1999, 35, 2779–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeschbach-Hertig, W.; Peeters, F.; Beyerle, U.; Kipfer, R. Palaeotemperature reconstruction from noble gases in ground water taking into account equilibration with entrapped air. Nature 2000, 405, 1040–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stute, M.; Forster, M.; Frischkorn, H.; Serejo, A.; Clark, J.; Schlosser, P.; Broecker, W.; Bonani, G. Cooling of tropical Brazil (5 °C) during the Last Glacial Maximum. Science 1995, 269, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capture® 8. Capture® 8 Pro+Lite Editions. Available online: https://durridge.com/documentation/capture_help/vers_8.1.7/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- European Parliament; Council of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2020/2184 of 16 December 2020 on the quality of water intended for human consumption (recast). Off. J. Eur. Union 2020, L 435, 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Muryanto, S.; Bayuseno, A.P. Scaling of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) in pipes: Effect of flow rates and calcium carbonate concentration. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2014, 9, 10653–10663. [Google Scholar]

- Falsini, S.; Boschetti, C.; Capobianco, G. Analysis of calcium carbonate scales in water distribution systems and influence of the electromagnetic treatment. Water 2024, 16, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özden, S.; Gündüz, O.; Sarikaya, O.; Başoğlu, A.; Bayram, A. Major factors affecting soil radon emanation. Nat. Hazards 2022, 110, 2913–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukanya, S.; Joseph, S. Radon distribution in groundwater and river water. In Environmental Radon; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 53–87. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).