Interannual Variability in Seasonal Sea Surface Temperature and Chlorophyll a in Priority Marine Regions of the Northwest of Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

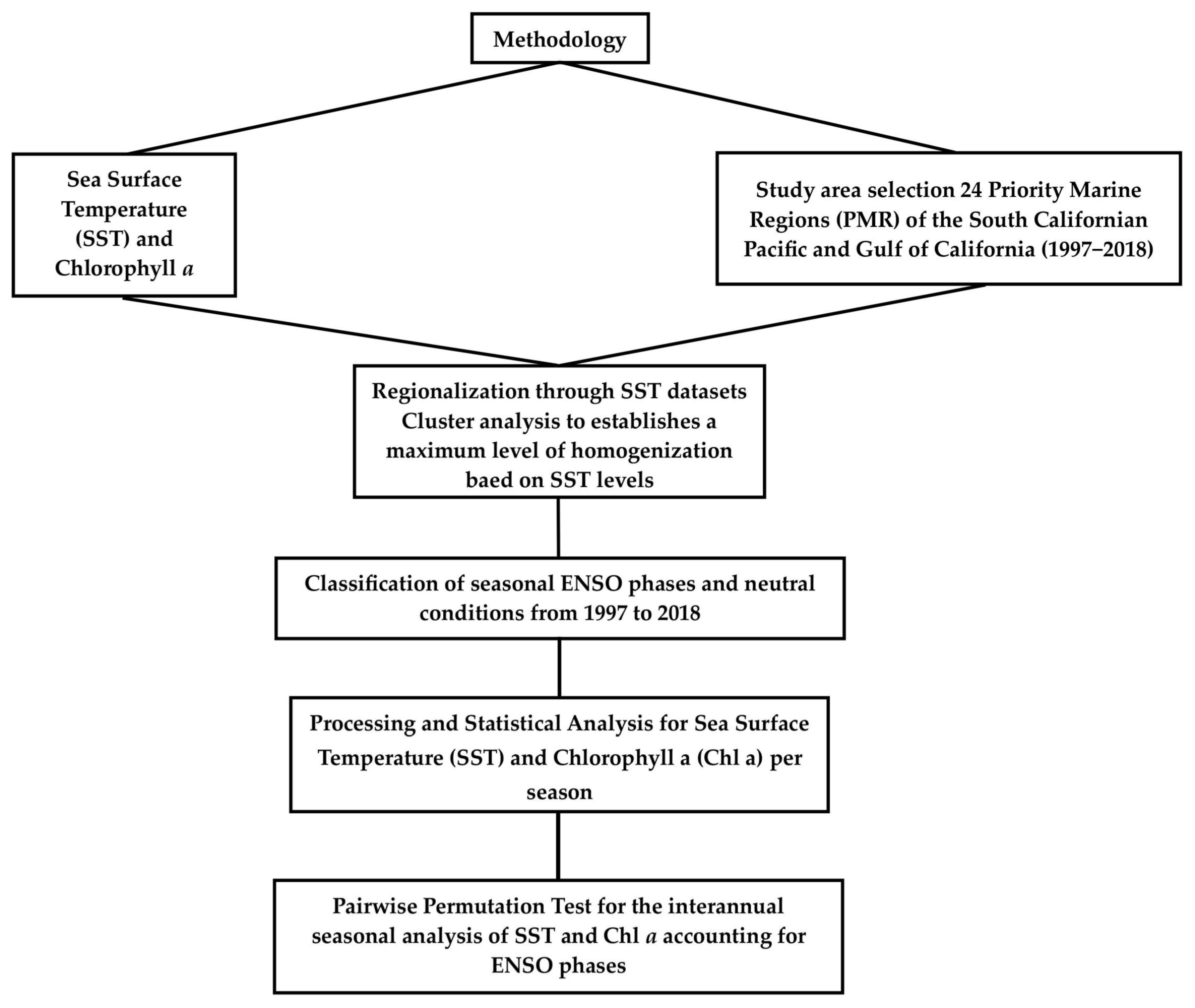

2. Materials and Methods

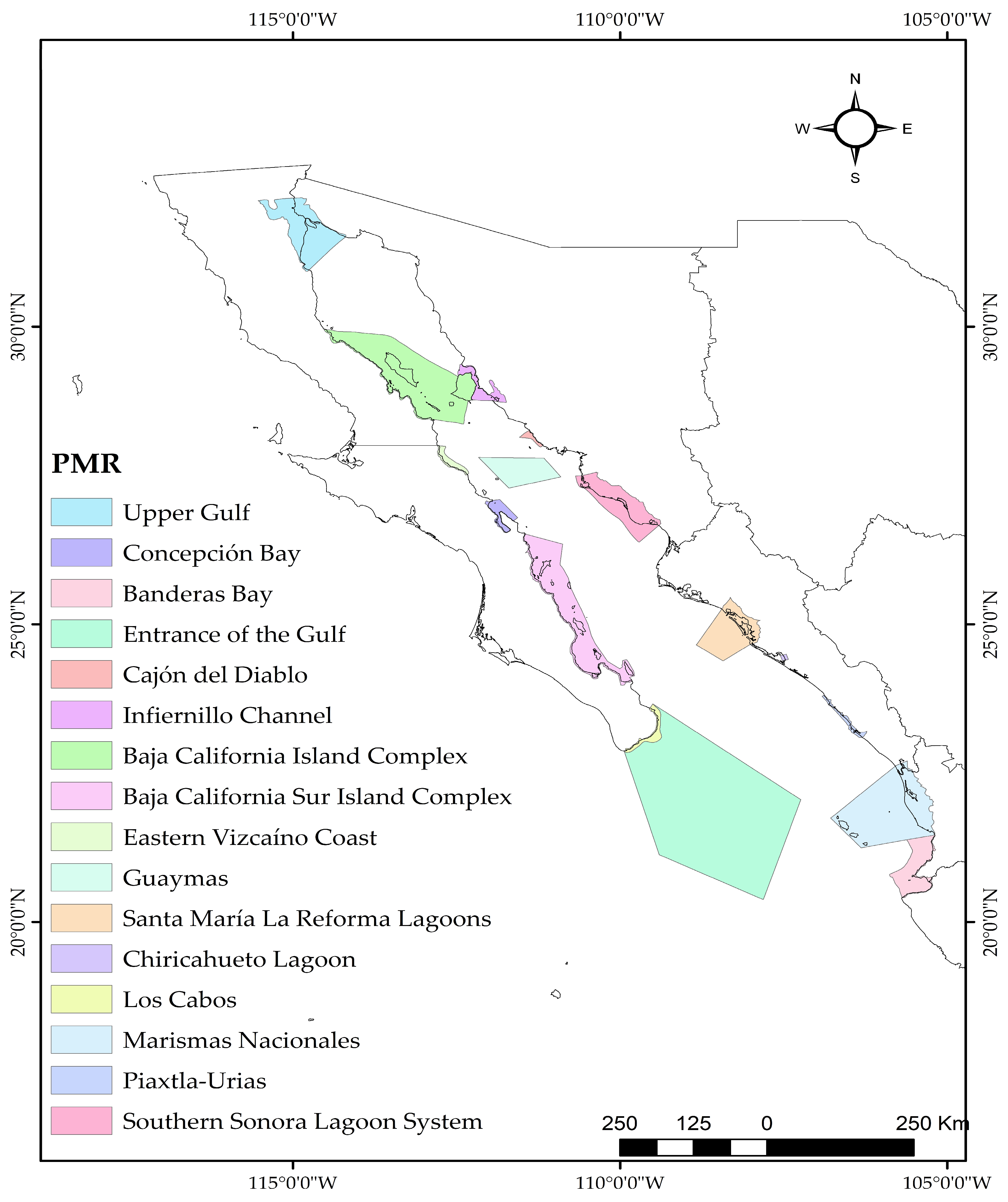

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sea Surface Temperature (SST) and Chlorophyll a (Chl a) Datasets

2.3. Processing Calibration and Regionalization Through Sea Surface Temperature (SST) Datasets

2.4. Processing and Statistical Analysis for Sea Surface Temperature (SST) and Chlorophyll a (Chl a)

3. Results

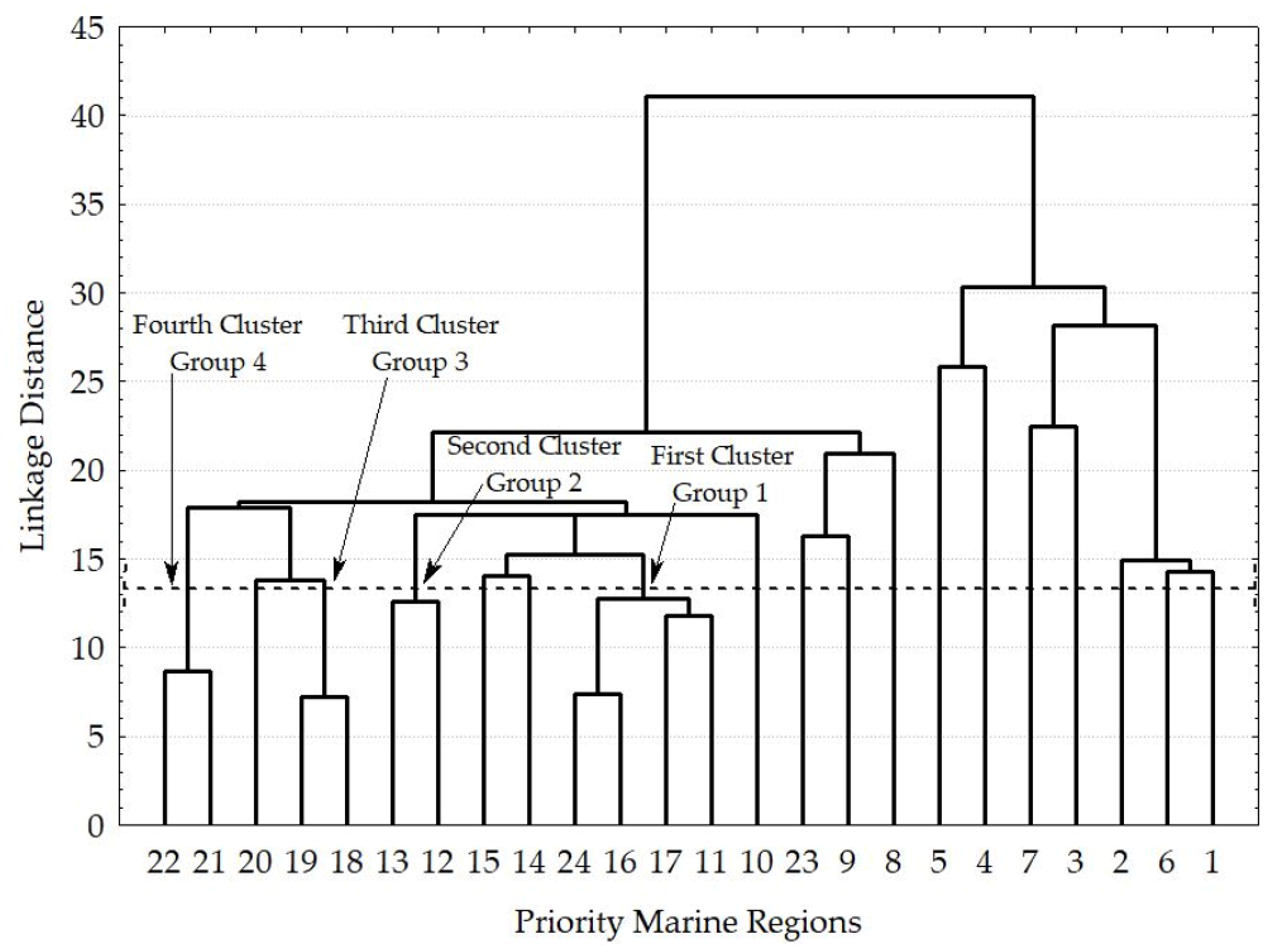

3.1. Datasets and Regionalization

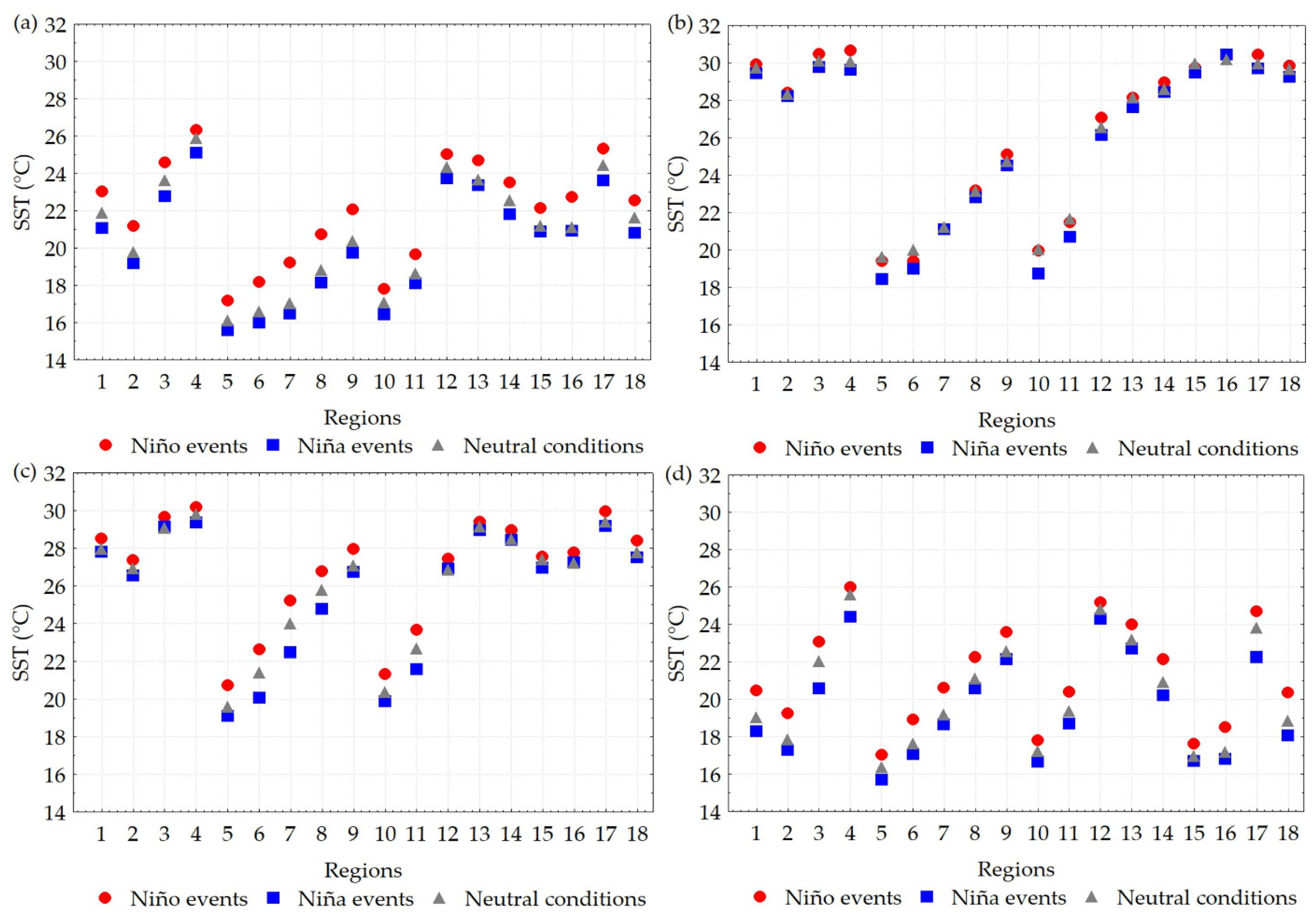

3.2. Interannual Analysis of ENSO: Sea Surface Temperature (SST)

3.3. Interannual Analysis of ENSO: Chlorophyll a (Chl a)

4. Discussion

4.1. Priority Marine Regions Aggregation

4.2. Interannual Analysis of ENSO: Sea Surface Temperature (SST) and Chlorophyll a (Chl a) Variability in the South Californian Pacific and Gulf of California

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Álvarez-Borrego, S. Physical, chemical and biological oceanography of the Gulf of California. In The Gulf of California: Biodiversity and Conservation, 2nd ed.; Brusca, R., Ed.; The University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2010; pp. 24–48. ISBN 978-0816500109. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Borrego, S. Phytoplankton Biomass in the Gulf of California: A review. Bot. Mar. 2012, 55, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazo, R. Climate and upper ocean variability off Baja California, Mexico: 1997–2008. Prog. Oceanogr. 2009, 83, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazo, R. Seasonality of the transitional region of the California Current System off Baja California. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2015, 120, 1173–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, J. Global Warming. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2005, 68, 1343–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doney, S.C.; Ruckelshaus, M.; Duffy, J.E.; Barry, J.P.; Chan, F.; English, C.A.; Galindo, H.M.; Grebmeier, J.M.; Hollowed, A.B.; Knowlton, N.; et al. Climate change impacts on marine ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2012, 4, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziqi, L. Impacts of global warming on marine ecosystems: Ocean acidification and fish catches. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Materials Chemistry and Environmental Engineering, Applied and Computational Engineering, London, UK, 13 January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Abraham, J.; Hausfather, Z.; Trenberth, K.E. How fast are the oceans warming? Science 2019, 363, 128–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Abraham, J.; Trenberth, K.E.; Fasullo, J.; Boyer, T.; Locarnini, R.; Zhang, B.; Yu, F.; Wan, L.; Chen, X.; et al. Upper Ocean Temperatures Hit Record High in 2020. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 38, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Wei, Y.; Lu, W.; Yan, X.-H.; and Zhang, H. Unabated Global Ocean Warming Revealed by Ocean Heat Content from Remote Sensing Reconstruction. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga-Cabrera, L.; Aguilar, A.; Espinoza, J.M. Regiones Marinas y Planeación Para la Conservación de la Biodiversidad. In Capital Natural de México. Vol. II: Estado de Conservación y Tendencias de Cambio, 1st ed.; Dirzo, R., González, R., March, I.J., Eds.; Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, CONABIO: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2009; Volume 2, pp. 433–457. [Google Scholar]

- Filipponi, F.; Valentini, E.; Taramelli, A. Sea Surface Temperature changes analysis, an Essential Climate Variable for Ecosystems Service Provisioning. In Proceedings of the 2017 9th International Workshop of Multitemporal Remote Sensing Images (MultiTemp2017), Brugge, Belgium, 27–29 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tokioka, T. Influence of the ocean on the atmospheric global circulations and short-range climatic fluctuations. In Proceedings of the Expert Consultation to Examine Change in Abundance and Species of Neritic Fish Resources, San José, Costa Rica, 18–29 April 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Fingas, F. Chapter 5—Remote Sensing for Marine Management. In World Seas: An Environmental Evaluation: Volume III: Ecological Issues and Environmental Impacts, 2nd ed.; Sheppard, C., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2019; pp. 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Gaxiola-Castro, G.; Cepeda-Morales, J.C.A.; Nájera-Martínez, S.; Espinosa-Carreón, T.L.; De la Cruz-Orozco, M.E.; Sosa-Avalos, R.; Aguirre-Hernández, E.; Cantú-Ontiveros, J.P. Biomasa y Producción de Fitoplancton. In Dinámica del Ecosistema Pelágico Frente a Baja California, 1997–2007. Diez Años de Investigaciones Mexicanas de la Corriente de California, 1st ed.; Gaxiola-Castro, G., Durazo-Arvizu, R., Eds.; Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales: Delegación Tlalpan, Mexico, 2010; pp. 59–85. [Google Scholar]

- Eisner, L.B.; Gann, J.C.; Ladd, C.; Cieciel, K.D.; Mordy, C.W. Late summer/early fall phytoplankton biomass (chlorophyll a) in the eastern Bering Sea: Spatial and temporal variations and factors affecting chlorophyll a concentrations. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2016, 134, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiela, I. Marine Ecological Processes, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, G.D.G.; Hughes, A.R.; Hultgren, K.M.; Miner, B.G.; Sorte, C.J.B.; Thornber, C.S.; Rodríguez, L.F.; Tomanek, L.; Williams, S.L. The impacts of climate change in coastal marine ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, D.G.; Lewis, M.R.; Worm, B. Global phytoplankton decline over the past century. Nature 2010, 466, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, D.G.; Down, M.; Lewis, M.R.; Worm, B. Estimating phytoplankton over the past century. Prog. Oceanogr. 2014, 122, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, M.A.; Scott, J.D.; Friedland, K.D.; Mills, K.E.; Nye, J.A.; Pershing, A.J.; Thomas, A.C. Projected Sea Surface Temperature over the 21st century: Changes in the mean, variability and extremes for large marine ecosystems regions of Northern Oceans. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2018, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierley, A.S.; Kingsford, M.J. Impacts of climate change on Marine Organism and Ecosystems. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, 602–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Bruno, J.F. The impacts of Climate Change on the World’s Marine Ecosystems. Science 2010, 328, 1523–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Arroyo, A.; Manzanilla-Naim, S.; Zavala-Hidalgo, J. Vulnerability to Climate change of marine and coastal fisheries. Atmósfera 2011, 24, 103–123. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, C.L.; Somero, G.N. The impact of ocean warming on marine organisms. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2014, 59, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, Z.; Yu, J.-Y.; Hu, X.; Dong, W.; He, S. El Niño–Southern Oscillation and its impact in the changing climate. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2018, 5, 840–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odériz, I.; Silva, R.; Mortlock, T.R.; Mori, N. El Niño-Southern Oscillation Impacts on Global Wave Climate and Potential Coastal Hazards. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2020, 125, e2020JC016464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, M.; Azevedo, A. El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) Variations and Climate Changes Worldwide. Atmos. Clim. Sci. 2024, 14, 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Rohli, R.V.; Vega, A. Climatology, 4th ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Vikas, M.; Dwarakish, G.S. El Niño: A Review. Int. J. Earth Sci. Eng. 2015, 8, 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Soni, A.; Singh, P. A Review Paper on El Niño. Int. J. Innov. Res. Eng. Manag. 2022, 9, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenberth, K.E. The definition of El Niño. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1997, 78, 2771–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Carreón, T.L.; Strub, P.T.; Beier, E.; Ocampo-Torres, F.; Gaxiola-Castro, G. Seasonal and interannual variability of satellite-derived chlorophyll pigment, surface height, and temperature off Baja California. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2004, 109, C03039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazo, R.; Castro, R.; Miranda, L.E.; Delgadillo-Hinojosa, F.; Mejía-Trejo, A. Anomalous hydrographic conditions off the northwestern coast of the Baja California Peninsula during 2013–2016. Cienc. Mar. 2017, 43, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Quiroz, M.C.; Cervantes-Duarte, R.; Funes-Rodríguez, R.; Barón-Campis, S.A.; García-Romero, F.J.; Hernández-Trujillo, S.; Hernández-Becerril, D.U.; González-Armas, R.; Martell-Dubois, R.; Cerdeira-Estrada, S.; et al. Impact of “The Blob” and “El Niño” in the SW Baja California Peninsula: Plankton and Environmental Variability of Bahia Magdalena. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Quiroz, M.C.; Barrón-Barraza, F.J.; Cervantes-Duarte, R.; Funes-Rodríguez, R.; González-Armas, R. Differences in the impact of intense ENSO+ in Bahia Magdalena (SW of Baja California, Mexico) in the context of climate change. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 80, 103864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lluch-Cota, S.E.; Parés-Sierra, A.; Magaña-Rueda, V.O.; Arreguín-Sánchez, F.; Bazzino, G.; Herrera-Cervantes, H.; Lluch-Belda, D. Changing climate in the Gulf of California. Prog. Oceanogr. 2010, 87, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, R.; López-Martínez, J.; Valdez-Holguín, J.E.; Herrera-Cervantes, H.; Espinosa-Chaurand, L.D. Environmental Variability and Oceanographic Dynamics of the Central and Southern Coastal Zone of Sonora in the Gulf of California. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Martínez, C.M.; Monreal-Gómez, M.A.; Coria-Monter, E.; Salas-de León, D.A.; Duran-Campos, E.; Merino-Ibarra, M. Three-dimensional distribution of nutrients and phytoplankton biomass in a semi-enclosed region of the Gulf of California during different ENSO phases. Bot. Mar. 2025, 68, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Acosta, J.D.; Cervantes-Duarte, R.; González-Rodríguez, E.; Gómez-Gutiérrez, J. Anomalously warm conditions decrease microphytoplankton abundance in Alfonso Basin, Southwest Gulf of California. Cont. Shelf Res. 2025, 296, 105582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeesh, R.; Dwarakish, G.S. Satellite oceanography—A review. Aquat. Procedia 2015, 4, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhurst, A.R. Ecological Geography of the Sea, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gayathri, K.D.; Ganasri, B.P.; Dwarakish, G.S. Applications of Remote in Satellite Oceanography: A review. Aquat. Procedia 2015, 4, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemas, V. Remote Sensing Techniques for studying Coastal Ecosystems: An Overview. J. Coast. Res. 2011, 27, 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gregg, W.W.; Conkright, M.E. Global seasonal climatologies of ocean chlorophyll: Blending in situ and satellite data for the Coastal Zone Color Scanner era. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2001, 106, 2499–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutkiewicz, S.; Hickman, A.E.; Jahn, O.; Henson, S.; Beaulieu, C.; Monier, E. Ocean Color Signature of Climate Change. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardoshi, T.; Golder, M.R.; Abdur-Rouf, M.; Ul-Alam, M.M. Seasonal and Spatial Variability of Chlorophyll-a in Response to ENSO and Ocean Current in the Maritime Boundary of Bangladesh. J. Mar. Sci. 2023, 2023, 2843608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.H.; Tian, F.; Shi, Q.; Wang, X.; Wu, T. Counteracting effects on ENSO induced by ocean chlorophyll interannual variability and tropical instability wave-scale perturbations in the tropical Pacific. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2024, 67, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Wan, X.; Wei, M.; Nie, H.; Qian, W.; Lu, X.; Zhu, L.; Feng, J. ENSO Significantly Changes the Carbon Sink and Source Pattern in the Pacific Ocean with Regional Differences. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Morriberón, D.; Mogollón, R.; Velasquez, O.; Yabar, G.; Villena, M.; Tam, J. Dynamics of Surface Chlorophyll and the Asymmetric Response of the High Productive Zone in the Peruvian Sea: Effects of El Niño and La Niña. Int. J. Clim. 2025, 45, e8764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría-del-Angel, E.; Álvarez-Borrego, S.; Muller-Karger, F.E. Gulf of California biogeographic regions based on coastal zone color scanner imagery. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 1994, 99, 7411–7421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Sánchez, M.C.; Valdez-Holguín, J.E.; Garatuza-Payán, J.; Cisneros-Mata, M.A.; Díaz-Tenorio, L.M.; Robles-Morua, A.; Hazas-Izquierdo, R.G. Regiones del Golfo de California determinadas por la distribución de la Temperatura Superficial del Mar y la concentración de Clorofila-a. Biotecnia 2018, 21, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría-del-Angel, E.; González-Silvera, A.; Millán-Núñez, R.; Callejas-Jiménez, M.E.; Cajal-Medrano, R. Determining Dynamic Biogeographic Regions Using Remote Sensing Data. In Handbook of Satellite Remote Sensing Image Interpretation: Applications for Marine Living Resources Conservation and Management, 1st ed.; Morales, J., Stuart, V., Platt, T., Sathyendranath, S., Eds.; EU PRESPO and IOCCG: Dartmouth, NS, Canada, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 273–293. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A.C.; Strub, P.T.; Weatherbee, R.A.; James, C. Satellite views of Pacific chlorophyll variability: Comparisons to physical variability, local versus nonlocal influences and links to climate indices. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2012, 77–80, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Cervantes, H.; Lluch-Cota, S.E.; Lluch-Cota, D.B.; Gutiérrez-de-Velasco, G. Interannual correlations between sea surface temperature and concentration of chlorophyll pigment off Punta Eugenia, Baja California, during different remote forcing conditions. Ocean Sci. 2014, 10, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Dong, Q.; Xue, C.; Wu, S. Seasonal and interannual variability of chlorophyll-a and associated physical synchronous variability in the western tropical Pacific. J. Mar. Sys. 2016, 158, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseaux, C.S.; Gregg, W.W. Climate variability and phytoplankton composition in the Pacific Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. 2012, 117, C10006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, A.B.; Holbrook, N.J.; Maharaj, A.M. Unravelling Eastern Pacific and Central Pacific ENSO Contributions in South Pacific Chlorophyll-a Variability through Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 4067–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Silvera, A.; Santamaría-Del-Ángel, E.; Camacho-Ibar, V.; López-Calderón, J.; Santander-Cruz, J.; Mercado-Santana, A. The Effect of Cold and Warm Anomalies on Phytoplankton Pigment Composition in Waters off the Northern Baja California Peninsula (México): 2007–2016. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Kug, J.S.; Park, J.; Yeh, S.W.; Jang, C.J. Variability of chlorophyll associated with El Niño–Southern Oscillation and its possible biological feedback in the equatorial Pacific. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2011, 116, C10001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.G.; Oh, J.H.; Kug, J.S. Delayed ENSO impact on phytoplankton variability over the Western-North Pacific Ocean. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 101006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tensubaum, C.M.; Babanin, A.; Dash, M.K. Fingerprints of El Niño Southern Oscillation on global and regional oceanic chlorophyll-a timeseries (1997–2022). Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 176893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Morales, R.; Pérez-Lezama, E.L.; Shirasago-Germán, B. Influence of environmental variability of baleen whales (suborden Mysticeti) in the Gulf of California. Mar. Ecol. 2017, 38, e12479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farach-Espinoza, E.B.; López-Martínez, J.; García-Morales, R.; Nevarez-Martínez, M.O.; Ortega-García, S.; Lluch-Cota, D.B. Coupling oceanic mesoscale events with catches of the Pacific sardine (Sardinops sagax) in the Gulf of California. Prog. Oceanogr. 2022, 206, 102858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortíz-Ahumada, J.C.; Álvarez-Borrego, S.; Gómez-Valdés, J. Effects of seasonal and interannual events on satellite-derived phytoplankton biomass and production in the southernmost part of the California Current System during 2003–2016. Cienc. Mar. 2018, 44, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ocampo, E.; Gaxiola-Castro, G.; Durazo, R.; Beier, E. Effects of the 2013-2016 warm anomalies on the California Current phytoplankton. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2018, 151, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Cardenas, G.S.; Morales-Acuña, E.; Tenorio-Fernadez, L.; Gómez-Gutiérrez, J.; Cervantes-Duarte, R.; Aguíñiga-García, S. El Niño–Southern Oscillation Diversity: Effect on Upwelling Center Intensity and Its Biological Response. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Cervantes, H.; Lluch-Cota, S.E.; Cortés-Ramos, J.; Farfán, L.; Morales-Aspeitia, R. Interannual variability of surface satellite-derived chlorophyll concentration in the bay of La Paz, Mexico, during 2003–2018 period: The ENSO signature. Cont. Shelf Res. 2020, 209, 104254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Cabeza, J.A.; Herrera-Becerril, C.A.; Carballo, J.L.; Yáñez, B.; Álvarez-Sánchez, L.F.; Cardoso-Mohedano, J.G.; Ruíz-Fernandez, A.C. Rapid surface water warming and impact of the recent (2013–2016) temperature anomaly in shallow coastal waters at the eastern entrance of the Gulf of California. Prog. Oceanogr. 2022, 202, 102746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakspiel-Segura, C.; Martínez-López, A.; Delgado-Contreras, J.A.; Robinson, C.J.; Gómez-Gutiérrez, J. Temporal variability of satellite chlorophyll-a as an ecological resilience indicator in the central region of the Gulf of California. Prog. Oceanogr. 2022, 205, 102825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Martínez, J.; Farach-Espinosa, E.B.; Herrera-Cervantes, H.; García-Morales, R. Long-Term Variability in Sea Surface Temperature and Chlorophyll a Concentration in the Gulf of California. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran-Campos, E.; Salas-de-León, D.A.; Coria-Monter, E.; Monreal-Gómez, M.A.; Aldeco-Ramírez, J.; Quiroz-Martínez, B. ENSO effects in the southern Gulf of California estimated from satellite data. Cont. Shelf Res. 2023, 266, 105084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Miller, A.J.; Cornuelle, B.D.; Di Lorenzo, E. Changes in upwelling and its water sources in the California Current System driven by different wind force. Dynam. Atmos. Ocean. 2011, 52, 170–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, T.R.; Christensen, N. Coupling of the Gulf of California to large-scale interannual climatic variability. J. Mar. Res. 1985, 43, 825–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Borrego, S.; Lara-Lara, J.R. The physical environment and primary productivity of the Gulf of California. In The Gulf and Peninsular Province of the Californias, 1st ed.; Dauphin, J.P., Simoneit, B.R.T., Eds.; American Association of Petroleum Geologist: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1991; Volume 47, pp. 555–567. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick, K.A.; Podesta, G.P.; Evans, R. Overview of the NOAA/NASA Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer Pathfinder algorithm for sea surface temperature and associated matchup database. J. Geophys. Res. 2001, 106, 9179–9197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, K.S.; Kearns, E.J.; Halliwell, V.; Evans, R. AVHRR Pathfinder Version 5.0, Interim Version 5.0, and Version 5.1 Global 4km Sea Surface Temperature (SST) Data for 1981–2009. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. Dataset. 2004. Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/metadata/landing-page/bin/iso?id=gov.noaa.nodc:AVHRR_Pathfinder-NODC-v5.0_v5.1 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Casey, K.S.; Brandon, T.S.; Cornillon, P.; Evans, R. The Past, Present, and Future of the AVHRR Pathfinder SST Program. In Oceanography from Space, 1st ed.; Barale, V., Gower, J.F.R., Alberotanza, L., Eds.; Springer Dordrecht: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 273–287. [Google Scholar]

- Kahru, M. The California Current Merged Satellite-Derived 4-km Dataset. Available online: https://spg-satdata.ucsd.edu/CC4km/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Kahru, M.; Kudela, R.M.; Manzano-Sarabia, M.; Greg-Mitchell, B. Trends in the surface chlorophyll of the California Current: Merging data from multiple ocean color satellites. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2012, 77–80, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahru, M. WIM Automation Module (WAM) USER’S MANUAL. Available online: https://www.wimsoft.com/auto_module.htm (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Allega, L.; Cozzolino, E.; Pisoni, J.P.; Piccolo, M.C. Comparison of SST L3 products generated from the AVHRR and MODIS sensors in front of the San Jorge Gulf, Argentina. Rev. Teledetección 2017, 50, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Tamayo, C.M.; Valdez-Holguín, J.E.; García-Morales, R.; Figueroa-Preciado, G.; Herrera-Cervantes, H.; López-Martínez, J.; Enríquez-Ocaña, L.F. Sea Surface Temperature (SST) Variability of the Eastern Coastal Zone of the Gulf of California. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, B.S.; Landau, S.; Leese, M.; Stahl, D. Cluster Analysis, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2011; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Backhaus, K.; Erichson, B.; Gensler, S.; Weiber, R.; Weiber, T. Cluster Analysis. In Multivariate Analysis, 2nd ed.; Backhaus, K., Erichson, B., Gensler, S., Weiber, R., Weiber, T., Eds.; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2023; pp. 453–532. [Google Scholar]

- NOAA National Centers for Environmental Prediction. Historical El Nino/La Nina Episodes (1950-present). Cold & Warm Episodes by Season. Available online: https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/ensostuff/ONI_v5.php (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Berry, K.J.; Johnston, J.E.; Mielke, P.W., Jr. A Primer of Permutation Statistical Methods, 1st ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, K.J.; Kvamme, K.L.; Johnston, J.E.; Mielke, P.W., Jr. Permutation Statistical Methods with R, 1st ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lavín, M.F.; Beier, E.; Badan, A. Estructura hidrográfica y circulación del Golfo de California: Escalas estacional e interanual. In Contribuciones a la Oceanografía Física en México, 1st ed.; Lavín, M.F., Ed.; Unión Geofísica Mexicana: Ensenada, Mexico, 1997; pp. 141–172. [Google Scholar]

- Lavín, M.F.; Marinone, S.G. An Overview of the Physical Oceanography of the Gulf of California. In Nonlinear Processes in Geophysical Fluid Dynamics, 1st ed.; Velasco-Fuentes, O.U., Sheinbaum, J., Ochoa, J., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 173–204. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Xing, X.; Liu, H.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chai, F. The variability of chlorophyll-a and its relationship with dynamic factors in the basin of the South China Sea. J. Mar. Syst. 2019, 200, 103230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, K.A.; Al-Abdouli, K.; Ghebreyesus, D.T.; Petchprayoon, P.; Al-Hosani, N.; Sharif, H.O. Spatiotemporal Variability of Chlorophyll-a and Sea Surface Temperature, and Their Relationship with Bathymetry over the Coasts of UAE. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, B.F.; Salisbury, J.; Atwood, E.C.; Sathyendranath, S.; Mahadevan, A. Dominant timescales of variability in global satellite chlorophyll and SST revealed with a MOving Standard deviation Saturation (MOSS) approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 286, 113404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, R. Variabilidad Oceanográfica del Hábitat de Los Stocks de Sardinops sagax (Jenyns, 1842) (Clupeiformes: Clupeidae) en el Sistema de Corriente de California (1981–2005). Ph.D. Thesis, Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas-Instituto Politécnico Nacional, La Paz, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A.C.; Mendelssohn, R.; Mendelssohn, R. Background trends in California Current surface chlorophyll concentrations: A state-space view. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2013, 118, 5296–5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-de la Torre, B.; Aguirre-Gómez, R.; Gaxiola-Castro, G.; Álvarez-Borrego, S.; Gallegos-Cota, A.; Rosete-Vergés, F.; Bocco-Verdinelli, G. Ordenamiento ecológico marino: Propuesta metodológica. Hidrobiológica 2015, 25, 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Zaytsev, O.; Cervantes-Duarte, R.; Montante, O.; Gallegos-García, A. Coastal upwelling activity on the Pacific shelf of the Baja California Peninsula. J. Oceanogr. 2003, 59, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz-Orozco, M.E.; Gómez-Ocampo, E.; Miranda-Bojórquez, L.E.; Cepeda-Morales, J.; Durazo, R.; Lavaniegos, B.E.; Espinosa-Carreón, T.L.; Sosa-Avalos, R.; Aguirre-Hernández, E.; Gaxiola-Castro, G. Phytoplankton biomass and production off the Baja California Peninsula: 1997–2016. Cienc. Mar. 2017, 43, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Duarte, R.; López-López, S.; González-Rodríguez, E.; Futema-Jiménez, S. Ciclo estacional de nutrientes, temperatura, salinidad, clorofila a en Bahía Magdalena, BCS, México (2006–2007). CICIMAR Oceánides 2010, 25, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Fuentes, L.M.; Gaxiola-Castro, G.; Gómez-Ocampo, E.; Kahru, M. Effects of interannual events (1997–2012) on the hydrography and phytoplankton biomass of Sebastian Vizcaíno Bay. Cienc. Mar. 2016, 42, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Palacios-Hernández, E.; Argote-Espinosa, M.L.; Amador-Buenrostro, A.; Mancilla-Peraza, M. Simulación de la circulación barotrópica inducida por el viento en Bahía Sebastián Vizcaíno. BC Atmósfera 1996, 9, 171–188. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Pares-Sierra, A.; López, M.; and Pavía, E.G. Oceanografía Física del Océano Pacífico Nororiental. In Contribuciones a la Oceanografía Física en México, 1st ed.; Lavín, M.F., Ed.; Unión Geofísica Mexicana: Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico, 1997; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Durazo, R.; Ramírez-Manguilar, A.M.; Miranda, L.E.; Soto-Mardones, L.A. Climatología de las variables oceanográficas. In Dinámica del Ecosistema Pelágico Frente a Baja California, 1997–2007. In Diez Años de Investigaciones Mexicanas de la Corriente de California, 1st ed.; Gaxiola-Castro, G., Durazo-Arvizu, R., Eds.; Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales: Delegación Tlalpan, Mexico, 2010; pp. 25–57. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Álvarez-Borrego, S. Gulf of California. In Estuaries and Eclosed Seas, 1st ed.; Ketchum, B.H., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1983; pp. 427–449. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Cervantes-Duarte, R.; García-Romero, F.J. Características hidrográficas en el litoral de Bahía Magdalena, BCS, México durante El Niño 2015. CICIMAR Oceánides 2016, 31, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazo, R.; Baumgartner, T. Evolution of oceanographic conditions off Baja California: 1997–1999. Prog. Oceanogr. 2002, 54, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalante, F.; Valdez-Holguín, J.E.; Álvarez-Borrego, S.; Lara-Lara, J.R. Temporal and spatial variation of sea surface temperature, chlorophyll a, and primary productivity in the Gulf of California. Cienc. Mar. 2013, 39, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, J.M.; Marinone, S.G. Seasonal and interannual thermohaline variability in the Guaymas Basin in the Gulf of California. Cont. Shelf Res. 1987, 7, 715–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-González, R.M.; Álvarez-Borrego, S. Total and new production in the Gulf of California estimated from ocean color data from the satellite sensor SeaWiFS. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2004, 51, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Molina, L.L.; Álvarez-Borrego, S.; Lara-Lara, J.R.; Marinone, S.G. Annual and semiannual variations of phytoplankton biomass and production in the central Gulf of California estimated from satellite data. Cienc. Mar. 2013, 39, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Cervantes, H.; Lluch-Cota, D.B.; Lluch-Cota, S.E.; Gutiérrez-De Velasco, G. The ENSO signature in sea-surface temperature in the Gulf of California. J. Mar. Res. 2007, 65, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Carreón, T.L.; Gaxiola-Castro, G.; Durazo, R.; De la Cruz-Orozco, M.D.; Norzagaray-Campos, M.; Solana-Arellano, E. Influence of anomalous subarctic water intrusion on phytoplankton production off Baja California. Cont. Shelf Res. 2015, 92, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Tamayo, C.M.; García-Morales, R.; Valdez-Holguín, J.E.; Figueroa-Preciado, G.; Herrera-Cervantes, H.; López-Martínez, J.; Enríquez-Ocaña, L.F. Chlorophyll a Concentration Distribution on the Mainland Coast of the Gulf of California, Mexico. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Orozco, E. Análisis Volumétrico de las Masas de Agua del Golfo de California. Master’s Thesis, Centro de Investigación Científica y Educación de Ensenada, Ensenada, Mexico, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Robles-Tamayo, C.M.; García-Morales, R.; Romo-León, J.R.; Figueroa-Preciado, G.; Peñalba-Garmendia, M.C.; Enríquez-Ocaña, L.F. Variability of Chl a Concentration of Priority Marine Regions of the Northwest of Mexico. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-Morales, J.; Fernández-Vásquez, F.; Rivera-Caicedo, J.; Romero-Bañuelos, C.; Inda-Díaz, E.; Hernández-Almeida, O. Seasonal variability of satellite derived chlorophyll and sea surface temperature on the continental shelf of Nayarit, Mexico. Rev. Bio Cienc. 2017, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- López, M.; Candela, J.; Argote, M.L. Why does the Ballenas Channel have the coldest SST in the Gulf of California? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L11603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Arvizu, E.M.; Aragón-Noriega, E.A.; Espinosa-Carreón, T.L. Variabilidad estacional de clorofila a y su respuesta a condiciones El Niño y La Niña en el Norte del Golfo de California. Rev. Biol. Mar. Y Oceanogr. 2013, 48, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-León, M.R.; Álvarez-Borrego, S.; Turrent-Thompson, G.; Gaxiola-Castro, G.; Heckel-Dziendzielewski, G. Nutrient input from the Colorado River to the northern Gulf of California is not required to maintain a productive pelagic ecosystem. Cienc. Mar. 2015, 41, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Acosta, J.D.; Martínez-López, A. Anomalously low diatom fluxes during 2009–2010 at Alfonso Basin, Gulf of California. Prog. Oceanogr. 2022, 206, 102837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilly, W.; Markaida, U.; Danie, P.; Frawley, T.; Robinson, C.; Gómez-Gutierrez, J.; Hyun, D.; Soliman, J.; Pandey, P.; Rosenzweig, L. Long-term hydrographic changes in the Gulf of California and ecological impacts: A crack in the World’s Aquarium? Prog. Oceanogr. 2022, 206, 102857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, R.; Farach-Espinoza, E.B.; Herrera-Cervantes, H.; Nevares-Martínez, M.O.; López-Martínez, J. Long-term variability in sea surface temperature and chlorophyll-a concentration in the Pacific region off Baja California. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 208, 107156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Velasco, L.; Beier, E.; Godínez, V.M.; Barton, E.D.; Santamaría-del Angel, E.; Jiménez-Rosenberg, S.P.A.; Marinone, S.G. Hydrographic and fish larvae distribution during the “Godzilla El Niño 2015–2016” in the northern end of the shallow oxygen minimum zone of the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2017, 122, 2156–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Lugo, A.G.; Espinosa-Carreón, T.L.; Seminoff, J.A.; Hart, C.E.; Ley-Quiñonez, C.P.; Alonso-Aguirre, A.; Todd-Jones, T.; Zavala-Norzagaray, A.A. Movements of loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) in the Gulf of California: Integrating satellite telemetry and remotely sensed environmental variables. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2020, 100, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveyra-Bustamante, A.A.; Gómez-Gutiérrez, J.; González-Rodríguez, E.; Sánchez, C.; Schiariti, A.; Mendoza-Becerril, M.A. Seasonal variability of gelatinous zooplankton during an anomalously warm year at Cabo Pulmo National Park, Mexico. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2020, 48, 779–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Marine Area | Priority Marine Region | Upper Left Latitude/Lower Right Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | South Californian Pacific | Ensenadan | 32°31′48″ N/115°42′ W |

| 2 | South Californian Pacific | Vizcaíno | 28°57′36″ N/113°43′48″ W |

| 3 | South Californian Pacific | San Ignacio | 27°18′36″ N/112°46′48″ W |

| 4 | South Californian Pacific | Magdalena Bay | 25°47′24″ N/111°21′36″ W |

| 5 | South Californian Pacific | Barra de Malva-Cabo Falso | 25°47′24″ N/111°21′36″ W |

| 6 | South Californian Pacific | Guadalupe Island | 29°22′12″ N/118°2′24″ W |

| 7 | South Californian Pacific | Alijos Rock | 25°08′24″ N/115°32′24″ W |

| 8 | South Californian Pacific | Revillagigedo Islands | 21°05′24″ N/109°30′00″ W |

| 9 | Gulf of California | Los Cabos | 23°39′ N/109°21′36″ W |

| 10 | Gulf of California | Baja California Sur Island Complex | 26°31′48″ N/109°47′24″ W |

| 11 | Gulf of California | Concepcion Bay | 27°07′12″ N/111°33′ W |

| 12 | Gulf of California | Eastern Vizcaíno Coast | 27°59′24″ N/112°18′36″ W |

| 13 | Gulf of California | Baja California Island Complex | 29°57′36″ N/112°12′36″ W |

| 14 | Gulf of California | Upper Gulf | 32°10′12″ N/114°11′24″ W |

| 15 | Gulf of California | Infiernillo Channel | 29°22′12″ N/111°43′48″ W |

| 16 | Gulf of California | Cajón del Diablo | 28°16′48″ N/111°09′36″ W |

| 17 | Gulf of California | Southern Sonora Lagoon System | 27°34′12″ N/109°21′36″ W |

| 18 | Gulf of California | Santa María La Reforma Lagoons | 25°26′24″ N/107°49′48″ W |

| 19 | Gulf of California | Chiricahueto Lagoon | 24°29′24″ N/107°25′48″ W |

| 20 | Gulf of California | Piaxtla-Urías | 23°48′ N/106°13′48″ W |

| 21 | Gulf of California | Marismas Nacionales | 22°41′24″ N/105°9′36″ W |

| 22 | Gulf of California | Banderas Bay | 21°27′36″ N/105°11′24″ W |

| 23 | Gulf of California | Entrance of the Gulf | 22°51′ N/107°14′24″ W |

| 24 | Gulf of California | Guaymas | 27°49′12″ N/110°54′36″ W |

| Number | Marine Areas | Regions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gulf of California | Group 1 (Concepción Bay, Cajón del Diablo, Southern Sonora Lagoon System and Guaymas) |

| 2 | Gulf of California | Group 2 (Eastern Vizcaíno Coast and Baja California Island Complex) |

| 3 | Gulf of California | Group 3 (Santa María La Reforma Lagoons and Chiricahueto Lagoon) |

| 4 | Gulf of California | Group 4 (Marismas Nacionales and Banderas Bay) |

| 5 | South Californian Pacific | Ensenadan |

| 6 | South Californian Pacific | Vizcaíno |

| 7 | South Californian Pacific | San Ignacio |

| 8 | South Californian Pacific | Magdalena Bay |

| 9 | South Californian Pacific | Barra de Malva-Cabo Falso |

| 10 | South Californian Pacific | Guadalupe Island |

| 11 | South Californian Pacific | Alijos Rock |

| 12 | South Californian Pacific | Revillagigedo Islands |

| 13 | Gulf of California | Los Cabos |

| 14 | Gulf of California | Baja California Sur Island Complex |

| 15 | Gulf of California | Upper Gulf |

| 16 | Gulf of California | Infiernillo Channel |

| 17 | Gulf of California | Piaxtla-Urías |

| 18 | Gulf of California | Entrance of the Gulf |

| Regions | Spring | Summer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Niño | La Niña | Neutral Conditions | El Niño | La Niña | Neutral Conditions | |

| 1 | 23.04 (a) | 21.06 (b) | 21.86 (c) | 29.90 | 29.43 | 29.72 |

| 2 | 21.16 (a) | 19.19 (b) | 19.76 (c) | 28.41 | 28.20 | 28.32 |

| 3 | 24.58 (a) | 22.76 (b) | 23.62 (a) | 30.47 | 29.77 | 30.10 |

| 4 | 26.31 (a, b) | 25.11 (a) | 25.89 (b) | 30.66 (a) | 29.61 (b) | 30.07 (a, b) |

| 5 | 17.18 (a) | 15.58 (b) | 16.08 (b) | 19.38 (a, b) | 18.41 (a) | 19.61 (b) |

| 6 | 18.17 (a) | 16 (b) | 16.58 (c) | 19.38 | 18.97 | 19.98 |

| 7 | 19.22 (a) | 16.45 (b) | 17.01 (b) | 21.08 | 21.09 | 21.23 |

| 8 | 20.73 (a) | 18.12 (b) | 18.80 (c) | 23.16 | 22.79 | 23.14 |

| 9 | 22.07 (a) | 19.74 (b) | 20.36 (b) | 25.11 | 24.52 | 24.71 |

| 10 | 17.82 | 16.42 | 17.05 | 19.97 (a, b) | 18.74 (a) | 20.02 (b) |

| 11 | 19.64 (a) | 18.09 (b) | 18.64 (b) | 21.45 | 20.69 | 21.64 |

| 12 | 25.02 (a) | 23.73 (b) | 24.33 (a, b) | 27.05 (a) | 26.13 (b) | 26.55 (a, b) |

| 13 | 24.71 (a) | 23.35 (b) | 23.65 (b) | 28.14 | 27.63 | 28.13 |

| 14 | 23.51 (a) | 21.79 (b) | 22.54 (c) | 28.97 | 28.42 | 28.58 |

| 15 | 22.14 (a) | 20.88 (b) | 21.17 (b) | 29.74 (a) | 29.48 (a) | 29.95 (a, b) |

| 16 | 22.73 (a) | 20.93 (a, b) | 21.09 (b) | 30.41 | 30.45 | 30.17 |

| 17 | 25.32 (a) | 23.60 (b) | 24.45 (a) | 30.45 (a) | 29.71 (b) | 29.97 (a, b) |

| 18 | 22.53 (a) | 20.79 (b) | 21.61 (c) | 29.83 | 29.25 | 29.65 |

| Regions | Autumn | Winter | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Niño | La Niña | Neutral Conditions | El Niño | La Niña | Neutral Conditions | |

| 1 | 28.52 (a) | 27.81 (b) | 27.94 (a, b) | 20.46 (a) | 18.28 (b) | 19.01 (b) |

| 2 | 27.34 (a) | 26.54 (b) | 26.90 (a, b) | 19.26 (a) | 17.27 (b) | 17.83 (a, b) |

| 3 | 29.65 | 29.12 | 29.06 | 23.05 (a) | 20.57 (b) | 22.02 (a) |

| 4 | 30.18 (a) | 29.37 (b) | 29.81 (a, b) | 25.99 (a) | 24.41 (b) | 25.57 (a) |

| 5 | 20.73 (a) | 19.10 (b) | 19.57 (a, b) | 17.03 (a) | 15.69 (b) | 16.35 (a, b) |

| 6 | 22.62 (a) | 20.06 (b) | 21.41 (a) | 18.92 (a) | 17.06 (b) | 17.61 (a, b) |

| 7 | 25.21 (a) | 22.47 (b) | 23.98 (a) | 20.61 (a) | 18.65 (b) | 19.18 (b) |

| 8 | 26.77 (a) | 24.77 (b) | 25.77 (a, b) | 22.24 (a) | 20.59 (b) | 21.11 (a, b) |

| 9 | 27.95 (a) | 26.74 (b) | 27.06 (a, b) | 23.57 (a) | 22.14 (b) | 22.54 (a, b) |

| 10 | 21.30 (a) | 19.89 (b) | 20.37 (a, b) | 17.82 (a) | 16.67 (b) | 17.20 (a, b) |

| 11 | 23.67 (a) | 21.60 (b) | 22.66 (a) | 20.39 (a) | 18.68 (b) | 19.36 (a, b) |

| 12 | 27.45 | 26.90 | 26.86 | 25.16 (a) | 24.27 (b) | 24.80 (a, b) |

| 13 | 29.39 | 28.94 | 29.12 | 23.97 (a) | 22.68 (b) | 23.17 (a, b) |

| 14 | 28.97 | 28.43 | 28.46 | 22.15 (a) | 20.20 (b) | 20.90 (b) |

| 15 | 27.54 | 26.96 | 27.41 | 17.60 (a) | 16.68 (b) | 16.96 (a, b) |

| 16 | 27.76 | 27.25 | 27.20 | 18.52 (a) | 16.81 (b) | 17.17 (b) |

| 17 | 29.96 (a) | 29.16 (b) | 29.39 (a, b) | 24.71 (a) | 22.26 (b) | 23.79 (a) |

| 18 | 28.39 (a) | 27.50 (b) | 27.75 (b) | 20.37 (a) | 18.06 (b) | 18.83 (a) |

| Regions | Spring | Summer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Niño | La Niña | Neutral Conditions | El Niño | La Niña | Neutral Conditions | |

| 1 | 3.60 (a) | 7.82 (b) | 6.50 (b) | 1.66 | 2.46 | 1.90 |

| 2 | 7.89 | 8.21 | 7.61 | 3.58 | 3.94 | 3.78 |

| 3 | 9.17 (a) | 19.26 (b) | 12.18 (a) | 7.83 | 6.60 | 6.91 |

| 4 | 2.48 (a, b) | 14.62 (a) | 4.53 (b) | 2.97 (a, b) | 3.30 (a) | 2.04 (b) |

| 5 | 1.90 (a) | 3.79 (b) | 3.26 (b) | 1.66 | 1.90 | 1.92 |

| 6 | 1.94 (a) | 4.66 (b) | 3.47 (c) | 3.31 | 2.75 | 2.80 |

| 7 | 4.12 (a) | 10 (b) | 7.39 (b) | 10.53 | 8.81 | 8.76 |

| 8 | 2.31 (a) | 5.67 (b) | 4.11 (c) | 4.39 | 4.21 | 4.43 |

| 9 | 1.34 (a) | 4.35 (b) | 2.90 (c) | 2.74 | 2.69 | 3.30 |

| 10 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.43 (a) | 0.35 (a, b) | 0.33 (b) |

| 11 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.31 |

| 12 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.28 |

| 13 | 0.83 (a) | 2.35 (b) | 1.65 (c) | 1.82 | 1.90 | 1.87 |

| 14 | 1.67 (a) | 3.74 (b) | 3.35 (b) | 1.87 | 2.03 | 1.97 |

| 15 | 7.77 | 8.29 | 9.62 | 7.28 (a) | 7.71 (a, b) | 6.58 (a) |

| 16 | 13.53 (a) | 19.20 (b) | 16.90 (a, b) | 8.04 | 10.60 | 10.27 |

| 17 | 3.06 (a) | 13.69 (b) | 6.20 (a) | 2.28 | 3.41 | 2.15 |

| 18 | 0.52 (a) | 1.07 (b) | 0.72 (a) | 0.73 | 0.61 | 0.62 |

| Regions | Autumn | Winter | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Niño | La Niña | Neutral Conditions | El Niño | La Niña | Neutral Conditions | |

| 1 | 3.02 (a) | 4.11 (b) | 3.98 (a, b) | 4.84 (a) | 7.14 (b) | 5.95 (a, b) |

| 2 | 4.67 | 5.50 | 5.10 | 4.65 | 5.05 | 4.79 |

| 3 | 10.86 | 11.74 | 10.98 | 9.23 (a) | 15.08 (b) | 13.38 (b) |

| 4 | 2.12 (a) | 4.12 (a, b) | 3.40 (b) | 2.31 (a) | 6.13 (b) | 3.31 (a, b) |

| 5 | 0.99 (a) | 1.44 (b) | 1.32 (b) | 1.28 | 1.86 | 1.45 |

| 6 | 1.34 | 1.53 | 1.38 | 1.35 (a) | 2.06 (b) | 1.63 (a, b) |

| 7 | 1.86 | 2.27 | 1.94 | 1.74 (a) | 2.68 (b) | 2.14 (a, b) |

| 8 | 1.14 | 1.39 | 1.53 | 1.13 (a) | 1.79 (b) | 1.52 (a, b) |

| 9 | 0.52 (a) | 0.65 (b) | 0.63 (a, b) | 0.79 (a) | 1.50 (b) | 1.08 (a, b) |

| 10 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.46 |

| 11 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.47 | 0.43 | 0.49 |

| 12 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.36 |

| 13 | 0.58 (a) | 0.77 (a, b) | 0.79 (b) | 1.14 (a) | 2.58 (b) | 2.19 (b) |

| 14 | 1.11 | 1.35 | 1.18 | 2.61 (a) | 3.51 (b) | 3.28 (a, b) |

| 15 | 7.28 | 8.04 | 7.68 | 7.12 | 8.46 | 7.63 |

| 16 | 11.67 | 13.46 | 14.18 | 12.81 | 17.43 | 16.70 |

| 17 | 3.35 | 4.33 | 3.98 | 3.92 (a) | 11.14 (b) | 5.24 (a) |

| 18 | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.62 (a) | 0.94 (b) | 0.73 (a, b) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Robles-Tamayo, C.M.; Romo-León, J.R.; García-Morales, R.; Figueroa-Preciado, G.; Enríquez-Ocaña, L.F.; Peñalba-Garmendia, M.C. Interannual Variability in Seasonal Sea Surface Temperature and Chlorophyll a in Priority Marine Regions of the Northwest of Mexico. Water 2025, 17, 3227. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223227

Robles-Tamayo CM, Romo-León JR, García-Morales R, Figueroa-Preciado G, Enríquez-Ocaña LF, Peñalba-Garmendia MC. Interannual Variability in Seasonal Sea Surface Temperature and Chlorophyll a in Priority Marine Regions of the Northwest of Mexico. Water. 2025; 17(22):3227. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223227

Chicago/Turabian StyleRobles-Tamayo, Carlos Manuel, José Raúl Romo-León, Ricardo García-Morales, Gudelia Figueroa-Preciado, Luis Fernando Enríquez-Ocaña, and María Cristina Peñalba-Garmendia. 2025. "Interannual Variability in Seasonal Sea Surface Temperature and Chlorophyll a in Priority Marine Regions of the Northwest of Mexico" Water 17, no. 22: 3227. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223227

APA StyleRobles-Tamayo, C. M., Romo-León, J. R., García-Morales, R., Figueroa-Preciado, G., Enríquez-Ocaña, L. F., & Peñalba-Garmendia, M. C. (2025). Interannual Variability in Seasonal Sea Surface Temperature and Chlorophyll a in Priority Marine Regions of the Northwest of Mexico. Water, 17(22), 3227. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223227