Data Assimilation for a Simple Hydrological Partitioning Model Using Machine Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The predictive performance of the AIF is improved compared to that of the OL;

- The AIF will immediately respond to observed streamflow values and update itself with corresponding state variables;

- AIF will better predict streamflow than OL during periods of sustained non-precipitation.

2. Materials and Methods

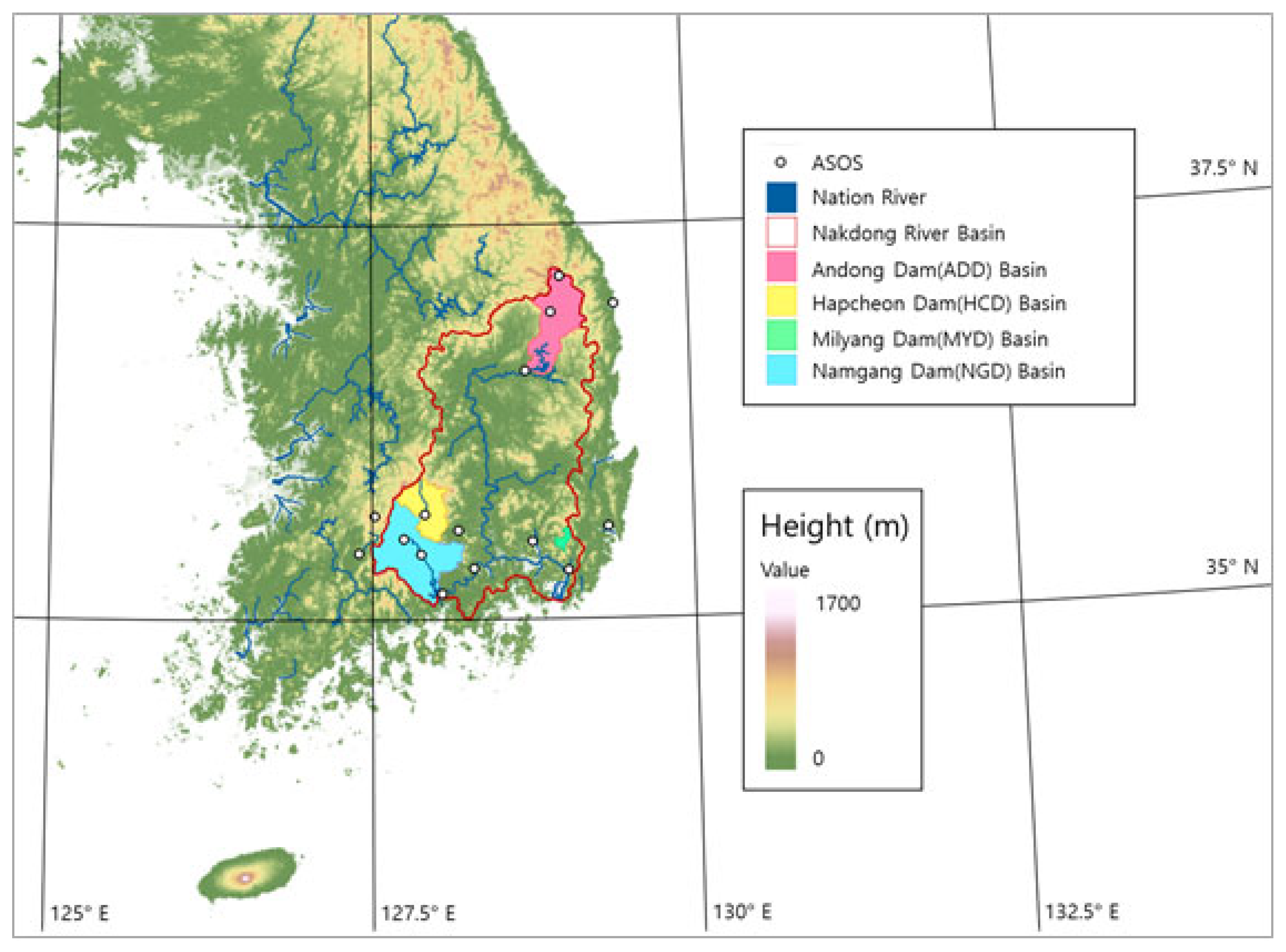

2.1. Data and Research Areas

2.2. Simple Hydrologic Partitioning Model

2.3. Artificial Intelligence Filter

- Open Loop:First, observed precipitation and PET data are input into the SHPM, which was developed to collect training data for AI. This generates Open Loop (OL) data, namely simulated streamflow and simulated state variables (soil moisture , aquifer water levels ).

- Train AI:AIF begins with the assumption that the relationship between the simulated streamflow and state variables and , modeled as OL, is identical to the relationship between the observed streamflow and the actual state variables and .where is the streamflow simulated by the SHPM, is the observed streamflow, is the observed precipitation, is the PET calculated by the PM method, is the soil moisture simulated by the SHPM, is the aquifer water level simulated by the SHPM, is the soil moisture corresponding to the observed streamflow, and is aquifer water level corresponding to the observed streamflow.Based on these assumptions, the AI model is trained to estimate soil moisture and aquifer water level by inputting streamflow , precipitation , and potential evapotranspiration . In this case, soil moisture and aquifer water level were trained as separate models to enable their independent updates.

- Data Assimilation:Direct insertion is the most basic data assimilation technique, replacing one or more simulated state variables with observations [19]. At this stage, since the AIF has already learned the relationship between the streamflow and the state variables and , providing the observed streamflow, observed precipitation , and potential evapotranspiration to the AIF allows it to calculate the estimates and for the state variables, even in the absence of observations for those variables.The new state variables and , estimated as AIF, are then passed back to the SHPM to update the state. The updated state variables are used to calculate the streamflow for the next time step.

- Strategy where only is updated when precipitation occurs and only is updated when non-precipitation occurs;

- Strategy where only is updated when precipitation occurs and both and are updated together when non-precipitation occurs;

- Strategy where both and are updated together when precipitation occurs and only is updated when non-precipitation occurs;

- Strategy where both and are updated regardless of precipitation occurrence.

- AIF estimating during precipitation;

- AIF estimating during precipitation;

- AIF estimating during non-precipitation;

- AIF estimating during non-precipitation.

2.4. Model Performance Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Parameter Estimation

3.2. Data Assimilation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vaze, J.; Post, D.A.; Chiew, F.H.S.; Perraud, J.M.; Viney, N.R.; Teng, J. Climate non-stationarity–validity of calibrated rainfall–runoff models for use in climate change studies. J. Hydrol. 2010, 394, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coron, L.; Andréassian, V.; Perrin, C.; Lerat, J.; Vaze, J.; Bourqui, M.; Hendrickx, F. Crash testing hydrological models in contrasted climate conditions: An experiment on 216 Australian catchments. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48, W05552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriasi, D.N.; Arnold, J.G.; Van Liew, M.W.; Bingner, R.L.; Harmel, R.D.; Veith, T.L. Model evaluation guidelines for systematic quantification of accuracy in watershed simulations. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, R.E. A new approach to linear filtering and prediction problems. J. Basic Eng. 1960, 82, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerts, A.H.; El Serafy, G.Y. Particle filtering and ensemble Kalman filtering for state updating with hydrological conceptual rainfall-runoff models. Water Resour. Res. 2006, 42, W09403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradkhani, H.; Sorooshian, S.; Gupta, H.V.; Houser, P.R. Dual state–parameter estimation of hydrological models using ensemble Kalman filter. Adv. Water Resour. 2005, 28, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.P.; Rupp, D.E.; Woods, R.A.; Zheng, X.; Ibbitt, R.P.; Slater, A.G.; Schmidt, J.; Uddstrom, M.J. Hydrological data assimilation with the ensemble Kalman filter: Use of streamflow observations to update states in a distributed hydrological model. Adv. Water Resour. 2008, 31, 1309–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.J.; Tachikawa, Y.; Shiiba, M.; Kim, S. Ensemble Kalman filtering and particle filtering in a lag-time window for short-term streamflow forecasting with a distributed hydrologic model. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2013, 18, 1684–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, D.H.; Jackson, B.M.; McGregor, J. Constraining the ensemble Kalman filter for improved streamflow forecasting. J. Hydrol. 2018, 560, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kim, S. Estimating time-varying parameters for monthly water balance model using particle filter: Assimilation of stream flow data. J. Korea Water Resour. Assoc. 2021, 54, 365–379. [Google Scholar]

- Jafarzadegan, K.; Abbaszadeh, P.; Moradkhani, H. Sequential data assimilation for real-time probabilistic flood inundation mapping. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2021, 2021, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lee, O.; Won, J.; Kim, S. Stochastic simple hydrologic partitioning model associated with Markov Chain Monte Carlo and ensemble Kalman filter. J. Korean Soc. Water Environ. 2020, 36, 353–363. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher, M.A.; Laliberté, J.P.; Anctil, F. An experiment on the evolution of an ensemble of neural networks for streamflow forecasting. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 14, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahart, R.J.; Anctil, F.; Coulibaly, P.; Dawson, C.W.; Mount, N.J.; See, L.M.; Shamseldin, A.Y.; Solomatine, D.P.; Toth, E.; Wilby, R.L. Two decades of anarchy? Emerging themes and outstanding challenges for neural network river forecasting. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2012, 36, 480–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.R.; Cannon, A.J.; Hsieh, W.W. Forecasting daily streamflow using online sequential extreme learning machines. J. Hydrol. 2016, 537, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, S. Utilization of the Long Short-Term Memory network for predicting streamflow in ungauged basins in Korea. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 182, 106699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.; Seo, J.; Lee, J.; Choi, J.; Park, Y.; Lee, O.; Kim, S. Streamflow predictions in ungauged basins using recurrent neural network and decision tree-based algorithm: Application to the southern region of the Korean peninsula. Water 2023, 15, 2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, J.W. Getting the right answers for the right reasons: Linking measurements, analyses, and models to advance the science of hydrology. Water Resour. Res. 2006, 42, W03S04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, M.A.; Quilty, J.; Adamowski, J. Data assimilation for streamflow forecasting using extreme learning machines and multilayer perceptrons. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR026226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalu, I.; Ndehedehe, C.E.; Okwuashi, O.; Eyoh, A.E.; Ferreira, V.G. An assimilated deep learning approach to identify the influence of global climate on hydrological fluxes. J. Hydrol. 2022, 614, 128498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Xu, T.; Chen, F.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, R.; Song, L.; Xu, Z.; et al. Improving regional climate simulations based on a hybrid data assimilation and machine learning method. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 1583–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeung, M.; Jang, J.; Yoon, K.; Baek, S.S. Data assimilation for urban stormwater and water quality simulations using deep reinforcement learning. J. Hydrol. 2023, 624, 129973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Kwon, M.; Cha, J.H.; Kim, D.H. High flow prediction model integrating physically and deep learning based approaches with quasi real-time watershed data assimilation. J. Hydrol. 2024, 636, 131304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, C.; Nan, T.; Ju, L.; Zhou, H.; Zeng, L. A novel deep learning approach for data assimilation of complex hydrological systems. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR035389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Zhang, J.; Cao, C.; Zheng, F. Parameter estimation and uncertainty quantification of rainfall-runoff models using data assimilation methods based on deep learning and local ensemble updates. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 185, 106332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghil, M.; Malanotte-Rizzoli, P. Data assimilation in meteorology and oceanography. Adv. Geophys. 1991, 33, 141–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouttier, F.; Courtier, P. Data Assimilation Concepts and Methods March 1999; Meteorological Training Course Lecture Series; ECMWF: Reading, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.K.; Xu, L. Data Assimilation for Atmospheric, Oceanic and Hydrologic Applications (Vol. II); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteith, J.L. Evaporation and environment. In Symposia of the Society for Experimental Biology; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK, 1965; Volume 19, pp. 205–234. [Google Scholar]

- Beven, K. A sensitivity analysis of the Penman-Monteith actual evapotranspiration estimates. J. Hydrol. 1979, 44, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration-Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements-FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 56; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, D.; Hao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, J. Uncertainty assessment of potential evapotranspiration in arid areas, as estimated by the Penman-Monteith method. J. Arid Land 2020, 12, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mockus, V. Section 4 Hydrology. In National Engineering Handbook; US Soil Conservation Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1964. Available online: https://irrigationtoolbox.com/NEH/Part%20630%20Hydrology/neh630-ch15.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Wałęga, A.; Rutkowska, A. Usefulness of the modified NRCS-CN method for the assessment of direct runoff in a mountain catchment. Acta Geophys. 2015, 63, 1423–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Metropolis, N.; Rosenbluth, A.W.; Rosenbluth, M.N.; Teller, A.H.; Teller, E. Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines. J. Chem. Phys. 1953, 21, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, W.K. Monte Carlo sampling methods using Markov chains and their applications. Biometrika 1970, 57, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilks, W.R.; Roberts, G.O. Strategies for improving MCMC. In Markov Chain Monte Carlo in Practice; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1996; pp. 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock, D.B. A history of the Metropolis–Hastings algorithm. Am. Stat. 2003, 57, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, J.E.; Sutcliffe, J.V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I—A discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 1970, 10, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, B.A.; Srinivasan, R.; Arnold, J.; Rewerts, C.; Brown, S.J. Nonpoint source (NPS) pollution modeling using models integrated with geographic information systems (GIS). Water Sci. Technol. 1993, 28, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.D.; Stieglitz, M. Comparing spatial and temporal transferability of hydrological model parameters. J. Hydrol. 2015, 525, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Kling, H.; Yilmaz, K.; Martinez, G. Decomposition of the mean squared error and NSE performance criteria: Implications for improving hydrological modelling. J. Hydrol. 2009, 377, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour, K.C.; Yang, J.; Maximov, I.; Siber, R.; Bogner, K.; Mieleitner, J.; Zobrist, J.; Srinivasan, R. Modelling hydrology and water quality in the pre-alpine/alpine Thur watershed using SWAT. J. Hydrol. 2007, 333, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.; Kang, H.; Choi, J.W.; Kong, D.S.; Gum, D.; Jang, C.H.; Lim, K.J. Application of SWAT-CUP for streamflow auto-calibration at Soyang-gang dam watershed. J. Korean Soc. Water Environ. 2012, 28, 347–358. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, R.; Won, J.; Choi, J.; Lee, O.; Kim, S. Application of Bayesian approach to parameter estimation of TANK model: Comparison of MCMC and GLUE methods. J. Korean Soc. Water Environ. 2020, 36, 300–313. [Google Scholar]

- Joh, H.; Park, J.; Jang, C.; Kim, S. Comparing prediction uncertainty analysis techniques of SWAT simulated streamflow applied to Chungju Dam watershed. J. Korea Water Resour. Assoc. 2012, 45, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Deng, G.; Liu, X.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, T.; Chen, Q.; Tang, Z. Remote sensing data assimilation to improve the seasonal snow cover simulations over the Heihe River Basin, Northwest China. Int. J. Climatol. 2024, 44, 5621–5640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Basin | Area (km2) | Period (Year) | Precipitaion (mm/Year) | PET (mm/Year) | Streamflow (mm/Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADD | 1584.00 | 2004–2014 | 1179.00 | 986.42 | 600.59 |

| 2014–2024 | 1110.23 | 1002.15 | 543.83 | ||

| HCD | 925.00 | 2004–2014 | 1306.85 | 1078.25 | 673.66 |

| 2014–2024 | 1201.27 | 1056.17 | 616.78 | ||

| MYD | 95.40 | 2004–2014 | 1330.80 | 1087.13 | 710.83 |

| 2014–2024 | 1405.29 | 1139.08 | 929.29 | ||

| NGD | 2285.00 | 2004–2014 | 1416.09 | 1064.46 | 1006.75 |

| 2014–2024 | 1426.81 | 1061.68 | 852.92 |

| Hyperparameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| n_estimators | 100 | Number of decision trees to generate |

| criterion | MSE | Tree splitting criteria |

| max_depth | None | Maximum depth of tree |

| min_samples_split | 2 | Maximum number of samples for node splitting |

| max_leaf_nodes | None | Maximum number of leaf nodes |

| Parameter | Basin | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADD | HCD | MYD | NGD | |

| 6.001 | 4.586 | 4.782 | 4.950 | |

| 262.950 | 407.365 | 211.183 | 307.956 | |

| 0.554 | 0.723 | 0.648 | 0.689 | |

| 169.536 | 134.132 | 143.295 | 145.789 | |

| 3.149 | 4.555 | 3.051 | 3.561 | |

| 0.852 | 0.804 | 0.744 | 0.738 | |

| R2 | 0.811 | 0.840 | 0.731 | 0.826 |

| NSE | 0.789 | 0.813 | 0.727 | 0.821 |

| KGE | 0.878 | 0.883 | 0.833 | 0.854 |

| pBias (%) | +6.37 | −3.06 | −0.81 | −6.85 |

| p-factor (%) | 53.82 | 61.24 | 69.53 | 78.62 |

| r-factor | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.29 |

| Simulation | R2 | NSE | KGE | pBias (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OL | 0.781 | 0.747 | 0.863 | +3.14 |

| EnKF 1 | 0.782 | 0.769 | 0.844 | −0.96 |

| EnKF 2 | 0.792 | 0.781 | 0.890 | −0.57 |

| EnKF 3 | 0.781 | 0.767 | 0.883 | −0.96 |

| EnKF 4 | 0.791 | 0.780 | 0.889 | −0.57 |

| AIF 1 | 0.790 | 0.779 | 0.885 | +2.78 |

| AIF 2 | 0.800 | 0.793 | 0.892 | +0.91 |

| AIF 3 | 0.784 | 0.770 | 0.885 | +0.64 |

| AIF 4 | 0.795 | 0.785 | 0.891 | −0.38 |

| Simulation | R2 | NSE | KGE | pBias (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OL | 0.797 | 0.790 | 0.890 | +0.62 |

| EnKF 1 | 0.823 | 0.817 | 0.904 | +1.52 |

| EnKF 2 | 0.832 | 0.828 | 0.908 | +0.35 |

| EnKF 3 | 0.823 | 0.818 | 0.904 | +1.53 |

| EnKF 4 | 0.832 | 0.829 | 0.908 | +0.36 |

| AIF 1 | 0.823 | 0.822 | 0.886 | +2.58 |

| AIF 2 | 0.839 | 0.839 | 0.885 | −1.00 |

| AIF 3 | 0.819 | 0.817 | 0.888 | +1.83 |

| AIF 4 | 0.835 | 0.835 | 0.887 | −1.31 |

| Simulation | R2 | NSE | KGE | pBias (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OL | 0.730 | 0.721 | 0.778 | +7.81 |

| EnKF 1 | 0.736 | 0.733 | 0.831 | +0.07 |

| EnKF 2 | 0.738 | 0.736 | 0.832 | +0.75 |

| EnKF 3 | 0.735 | 0.732 | 0.830 | +0.06 |

| EnKF 4 | 0.737 | 0.734 | 0.832 | +0.73 |

| AIF 1 | 0.754 | 0.753 | 0.815 | +3.25 |

| AIF 2 | 0.761 | 0.761 | 0.818 | +0.05 |

| AIF 3 | 0.748 | 0.747 | 0.827 | +0.37 |

| AIF 4 | 0.757 | 0.757 | 0.824 | −1.60 |

| Simulation | R2 | NSE | KGE | pBias (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OL | 0.796 | 0.781 | 0.891 | −0.24 |

| EnKF 1 | 0.793 | 0.777 | 0.887 | −2.68 |

| EnKF 2 | 0.798 | 0.786 | 0.892 | −1.71 |

| EnKF 3 | 0.791 | 0.774 | 0.885 | −2.66 |

| EnKF 4 | 0.796 | 0.783 | 0.891 | −1.70 |

| AIF 1 | 0.806 | 0.801 | 0.888 | +2.31 |

| AIF 2 | 0.816 | 0.814 | 0.890 | +0.53 |

| AIF 3 | 0.805 | 0.800 | 0.888 | +1.89 |

| AIF 4 | 0.815 | 0.813 | 0.890 | +0.31 |

| Simulation | R2 | Δ R2 | NSE | Δ NSE | KGE | Δ KGE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OL | 0.776 | - | 0.760 | - | 0.856 | - |

| EnKF 4 | 0.786 | 0.010 | 0.778 | 0.018 | 0.871 | 0.016 |

| AIF 4 | 0.797 | 0.021 | 0.793 | 0.033 | 0.878 | 0.023 |

| Dam | DA | Seg. L | Seg. D | Seg. M | Seg. W | Seg. H | Whole |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADD | OL | +47.00 | −2.62 | +4.17 | +4.68 | −0.04 | +3.14 |

| EnKF 2 | +46.31 | −4.31 | −2.44 | +1.92 | −4.72 | −0.57 | |

| AIF 2 | +70.04 | +1.47 | −5.38 | +2.14 | −3.63 | +0.91 | |

| HCD | OL | +18.25 | −3.90 | −1.87 | +5.12 | −5.18 | +0.62 |

| EnKF 2 | +21.99 | −2.88 | −2.59 | +4.48 | −3.64 | +0.35 | |

| AIF 2 | +27.44 | −0.33 | −2.54 | +1.04 | −6.32 | −1.00 | |

| MYD | OL | +92.04 | +23.69 | +15.22 | +11.20 | −10.46 | +7.81 |

| EnKF 2 | +52.36 | +1.51 | +1.94 | +1.94 | +7.62 | −10.03 | |

| AIF 2 | +60.12 | +1.62 | +0.25 | +6.53 | −10.75 | +0.05 | |

| NGD | OL | −15.43 | −11.32 | −2.32 | +11.50 | −3.95 | −0.24 |

| EnKF 2 | −8.01 | −9.03 | −3.43 | +6.08 | −4.55 | −1.71 | |

| AIF 2 | +6.57 | +0.35 | +0.47 | +5.63 | −6.17 | +0.53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeon, C.; Lee, C.; Jang, S.; Kim, S. Data Assimilation for a Simple Hydrological Partitioning Model Using Machine Learning. Water 2025, 17, 3204. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223204

Jeon C, Lee C, Jang S, Kim S. Data Assimilation for a Simple Hydrological Partitioning Model Using Machine Learning. Water. 2025; 17(22):3204. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223204

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeon, Changhwi, Chaelim Lee, Suhyung Jang, and Sangdan Kim. 2025. "Data Assimilation for a Simple Hydrological Partitioning Model Using Machine Learning" Water 17, no. 22: 3204. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223204

APA StyleJeon, C., Lee, C., Jang, S., & Kim, S. (2025). Data Assimilation for a Simple Hydrological Partitioning Model Using Machine Learning. Water, 17(22), 3204. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223204