Model-Driven Sewage System Design and Intelligent Management of the Wuhan East Lake Deep Tunnel Drainage Project

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Project Background

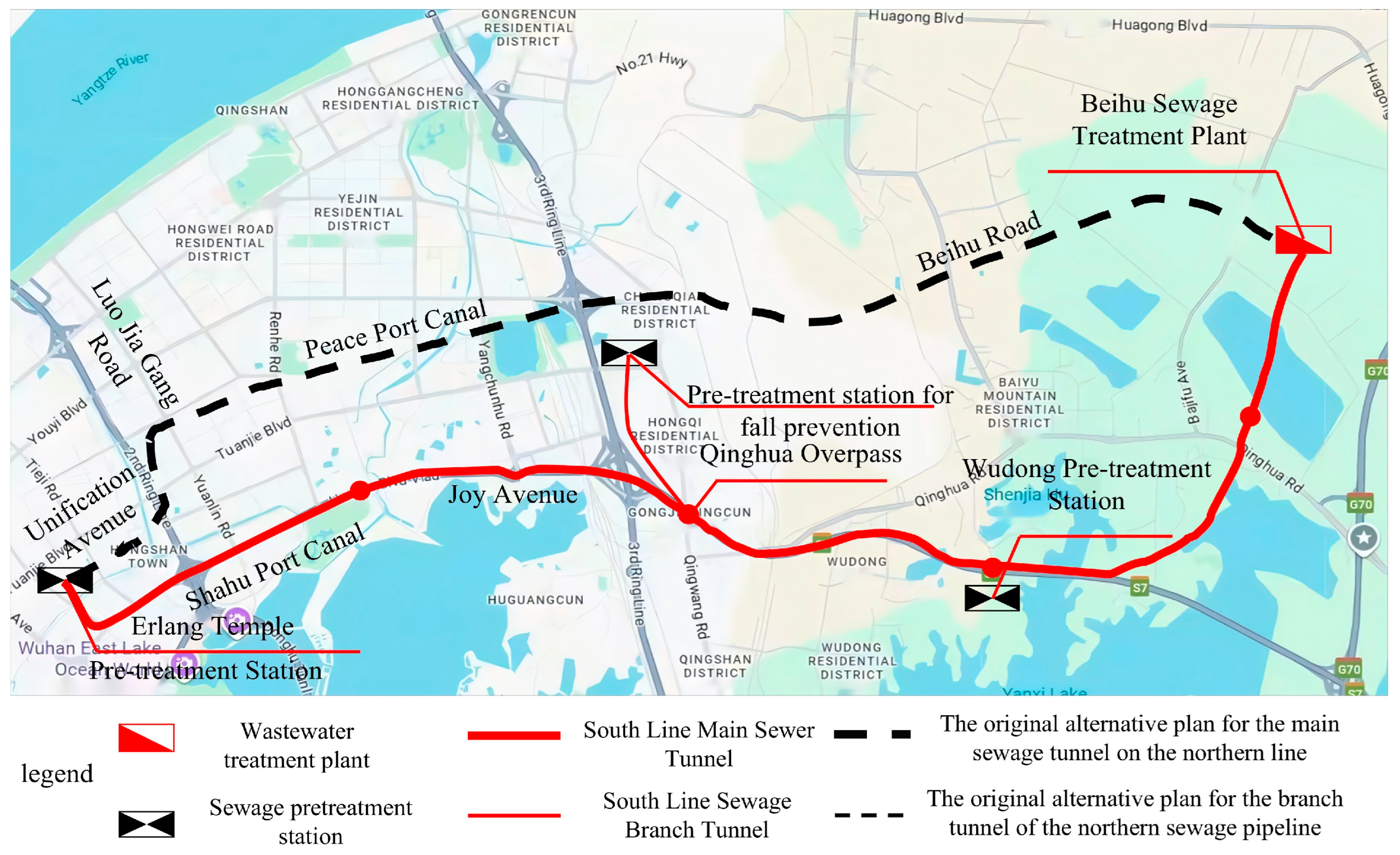

2.2. Overview of East Lake Drainage Scheme

2.3. Methodology and Models for East Lake Drainage Simulation

3. Result

3.1. Simulation Output Analysis and Intelligent Response

3.1.1. SWMM Modeling for East Lake Tunnel

3.1.2. Intelligent Operation and Anti-Sedimentation System

3.1.3. Operational Scenarios and Emergency Dispatch Simulation

3.2. Full-Process Sewage System Calculation and Analysis

3.2.1. Interception Points and Interception Methods

3.2.2. Node and Pipeline Flow in the Sewage Transmission System

3.2.3. Pretreatment Stations

3.2.4. Energy Dissipation and Noise Reduction in Inflow Shafts

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparative Analysis with the International Deep Tunnel Project

4.2. Assessment of System Benefits

4.3. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WWTP | Wastewater Treatment Plant |

| SWMM | Storm Water Management Model |

| ICM | InfoWorks Integrated Catchment Modeling |

| CFD-DEM | Computational Fluid Dynamics–Discrete Element Method |

| SS | Suspended Solids |

| CSO | Combined Sewer Overflow |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

References

- Sun, H.; Li, M.; Jiang, H.; Ruan, X.; Shou, W. Inundation Resilience Analysis of Metro-Network from a Complex System Perspective Using the Grid Hydrodynamic Model and FBWM Approach: A Case Study of Wuhan. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Zou, L.; Xia, J.; Dong, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yao, T. Assessment of the Urban Waterlogging Resilience and Identification of Its Driving Factors: A Case Study of Wuhan City, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 866, 161321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Q. The Trends, Promises and Challenges of Urbanisation in the World. Habitat Int. 2016, 54, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koné, D. Making Urban Excreta and Wastewater Management Contribute to Cities’ Economic Development: A Paradigm Shift. Water Policy 2010, 12, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieraj, J.; Bryx, M.; Metelski, D. Stormwater Management in the City of Warsaw: A Review and Evaluation of Technical Solutions and Strategies to Improve the Capacity of the Combined Sewer System. Water 2022, 14, 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wu, X.; Wang, G.; He, J.; Li, W. The Governance and Optimization of Urban Flooding in Dense Urban Areas Utilizing Deep Tunnel Drainage Systems: A Case Study of Guangzhou, China. Water 2024, 16, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.; Wang, S.; Fu, T.; Liu, J.; Han, L. Development History, Present Situation, and the Prospect of Subsurface Drainage Technology in China. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2021, 29, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Jing, L. Diagnosing Tunnel Collapse Sections Based on TBM Tunneling Big Data and Deep Learning: A Case Study on the Yinsong Project, China. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 108, 103700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Tan, L.; Xie, S.; Ma, B. Development and Applications of Common Utility Tunnels in China. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 76, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalise, C.; Fitzpatrick, K. Chicago Deep Tunnel Design and Construction. Struct. Congr. 2012, 2012, 1485–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.T.; Zhang, C.; Qiu, S.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, Q.; Li, S. Dynamic Design Method for Deep Hard Rock Tunnels and Its Application. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2016, 8, 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Yan, J.; Liang, W. Challenges and Development Prospects of Ultra-Long and Ultra-Deep Mountain Tunnels. Engineering 2019, 5, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Chen, B.; Li, S.; Zhang, C.; Xiao, Y.; Feng, G.; Ming, H. Studies on the Evolution Process of Rockbursts in Deep Tunnels. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2012, 4, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Xiao, Z.; Ye, F.; Tong, Y.; Cao, X.; Sun, J.; Li, Z. The Impact of Extreme Rainfall and Drainage System Failure on Rock Tunnels: A Case Study of Deep-Buried Karst Tunnel. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 171, 109345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, M.; Nietch, C.; Maghrebi, M.; Jackson, N.; Bennett, B.R.; Tryby, M.; Massoudieh, A. Storm Water Management Model: Performance Review and Gap Analysis. J. Sustain. Water Built Environ. 2017, 3, 04017002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuomela, C.; Sillanpää, N.; Koivusalo, H. Assessment of Stormwater Pollutant Loads and Source Area Contributions with Storm Water Management Model (SWMM). J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Chen, J.; Hu, H.; Tang, Y.; Huang, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, J. Urban Waterlogging Simulation and Disaster Risk Analysis Using InfoWorks Integrated Catchment Management: A Case Study from the Yushan Lake Area of Ma’anshan City in China. Water 2024, 16, 3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Wu, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J. Urban Flooding Simulation and Flood Risk Assessment Based on the InfoWorks ICM Model: A Case Study of the Urban Inland Rivers in Zhengzhou, China. Water Sci. Technol. 2024, 90, 1338–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, V. Thickness-Based Adaptive Mesh Refinement Methods for Multi-Phase Flow Simulations with Thin Regions. J. Comput. Phys. 2014, 269, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xie, Q.; Yang, J. Daily Suspended Sediment Forecast by an Integrated Dynamic Neural Network. J. Hydrol. 2022, 604, 127258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.K.; Mohseni, O.; Gulliver, J.S.; Stefan, H.G. Hydraulic Analysis of Suspended Sediment Removal from Storm Water in a Standard Sump. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2012, 138, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moler, W.; Lewis, D.; Crow, M.; Doig, P.; Cole, M.; Pyle, C.; Page, A. Case History of Tunnel Construction, Lower Northwest Interceptor Program. In Pipelines 2007: Advances and Experiences with Trenchless Pipeline Projects; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2007; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Feng, X.; Zhou, H.; Qiu, S.; Wu, W. A Top Pilot Tunnel Preconditioning Method for the Prevention of Extremely Intense Rockbursts in Deep Tunnels Excavated by TBMs. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2012, 45, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Yu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H. Hydraulic Characteristics of a Deep Tunnel System under Different Inflow Conditions. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 114103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 25031-2010; Technical Specification for Urban Stormwater Runoff Pollution Control Engineering. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Xu, J.; Lee, J.H.; Yin, K.; Liu, H.; Harrison, P.J. Environmental Response to Sewage Treatment Strategies: Hong Kong’s Experience in Long Term Water Quality Monitoring. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 2275–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Abbasi, N.S.; Pan, W.; Alidekyi, S.N.; Li, H.; Ahmed, B.; Asghar, A. A Review of Vertical Shaft Technology and Application in Soft Soil for Urban Underground Space. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.H.; Zhu, D.Z.; Sun, S.K.; Liu, Z.P. Experimental Study of Flow in a Vortex Drop Shaft. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2006, 132, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, G.J. Flow through Disposable Alternatives to the Laryngeal Mask. Anaesthesia 2003, 58, 280–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Zhou, C.; Dong, Z.; Zhou, Z. Numerical Simulation of Hydraulic Characteristics in a Vortex Drop Shaft. Water 2018, 10, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, H.; Jing, X.; Si, M.; Zeng, F.; Feng, R. The Coupled Cooling Effect of Ventilation and Spray in the Deep-Buried High-Temperature Tunnel. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 45, 103011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Pickles, D.; Whyte, F.; Yuen, E.; Ho, L. A cost-effective and innovative design of effluent tunnel and disinfection system for the Harbour Area Treatment Scheme (HATS) Stage 2, Hong Kong. Water Pract. Technol. 2012, 7, wpt2012088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Goh, J. Sustainable Energy from Wastewater: Hydroelectricity Potential in Singapore’s Deep Tunnel Sewerage System. In Proceedings of the IRC Conference on Science, Engineering and Technology; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.B.; Crawford, D. London Tideway Tunnels: Tackling London’s Victorian Legacy of Combined Sewer Overflows. Water Sci. Technol. 2011, 63, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuchi, K.; Maeda, M.; Shintani, Y. Sewer system for improving flood control in Tokyo: A step towards a return period of 70 years. Water Sci. Technol. 1994, 29, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Index | Deep Tunnel System | Traditional Drainage | Comparative Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Payback period | 15 to 50 years | 10 to 20 years | Short-term advantage of the traditional method |

| Land occupancy rate | Main tunnel: zero surface occupation; regulation tank: occupies 0.15 km2 | 2.6 km2 per plant (Shanghai case) | Deep tunnel saves 90% |

| Water Quality Compliance Rate | CSO control rate ≥ 92% (measured in 2023) | CSO control rate: 60–75% | Deep tunnel improves by 25% |

| Lake | Administrative Districts | Primary Water Function Zone | Lake Area (km2) | Water Quality Management Targets | 2014 Water Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Lake | East Lake Ecotourism Scenic Area | East Lake Development and Utilization Zone | 33.989 | Class III | Class IV |

| Sha Lake | Wuchang District East Lake Ecotourism Scenic Area | Sha Lake Preservation Zone | 3.078 | Class IV | Below Class V |

| Yangchun Lake | Hongshan District | Yangchun Lake Preservation Zone | 0.576 | Class IV | Class IV |

| Yanxi Lake | East Lake High-Tech Development Zone | Yanxi Lake Preservation Zone | 14.231 | Class III | Class IV |

| Yandong Lake | East Lake High-Tech Development Zone | Yandong Lake Preservation Zone | 9.111 | Class III | Class IV |

| Bei Lake | Qingshan District | Bei Lake Development and Utilization Zone | 1.933 | Class V | Class IV |

| Indicator | Conventional CFD-DEM Model | ICM/CFD-DEM-AI Model of This Project | Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sedimentation Prediction Error | 38.5% | 4.3% | 89% |

| Dredging Localization Accuracy | ±3.2 m | ±0.5 m | 84% |

| Response Delay | 2.1 h | 8 min | 94% |

| Data Type | Example Parameters | Collection Method | Update Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Velocity/Discharge | Radar Flow Velocity Meter (v), Ultrasonic Flow Meter (Q) | 50 m/point Fiber Optic Sensor Network | 100 Hz |

| Water Quality Parameters | Turbidity (NTU), TP, COD, H2S | Multispectral Online Monitoring Instrument | 5 min |

| Structural Condition | Lining Strain (με), Joint Displacement (mm) | Distributed Fiber Optic Sensing (DTS) | Deep Tunnel Improvement of 25% |

| Historical Operation and Maintenance | Dredging Volume (m3), Corrosion Depth (mm/year) | Robotic Scanning Database | Event Trigger |

| Rainfall Forecast | Rainfall Intensity for the Next 3 Hours (mm/h), Storm Return Period | Meteorological Radar + Machine Learning Forecasting | 15 min |

| Topography and Geology | Pipe Slope (‰), Soil and Rock Permeability Coefficient (cm/s) | BIM Geological Model | Static Parameters |

| Stage | Technical Scheme | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Triggering Mechanism for Desilting | Real-time Sediment Monitoring + Hydraulic Model Prediction | Initiated when sediment thickness ≥ 0.3 m or flow velocity < 0.8 m/s |

| Main Desilting Approach | High-pressure Hydraulic Flushing + Negative-pressure Suction (No Mechanical Entry into Tunnel) | Flushing pressure ≥ 35 MPa; suction flow rate 300 m3/h |

| Sludge Treatment | In situ Pipeline Dewatering + On-ground Centrifugal Dewatering | Moisture content reduced from 98% to below 60% |

| Resource Utilization | Dewatered Sludge Utilized for Lightweight Aggregate Production (Resource Utilization Rate > 85%) | Compliant with Sludge Disposal for Brick-making in Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants (GB/T 25031-2010) [25] |

| Technology Aspect | London Thames Tideway Tunnel | Tokyo Metropolitan Outer Area Underground Discharge Channel | Wuhan East Lake Deep Tunnel |

|---|---|---|---|

| Velocity Monitoring Density | 500 m per point | 300 m per point | 50 m per point |

| Sedimentation Prediction Model | Empirical Formula | Two-dimensional Hydrodynamic Model | CFD-DEM-AI Coupled Model |

| Response Timeliness | Manual Analysis (≥4 h) | Semi-automatic (≈1 h) | Fully automatic (≤10 min) |

| Desilting Accuracy | ±5 m | ±3 m | ±0.5 m |

| Near-Term Capacity (2024) | Long-Term Capacity (2049) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Dry Season Flow | Peak Dry Season Flow | Rainy Season Flow | Dry Season Capacity | Dry Season Capacity | ||

| North Line Sewage Deep Tunnel | Shahu Pumping Station | 0.77 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.77 | 0.77 |

| Erlangmiao Node | 5.67 | 7.37 | 9.8 | 6.37 | 8.28 | |

| Luobuzui Node | 2.3 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.4 | 5.72 | |

| Wudong Node | 0.4 | 0.52 | 2.4 | 0.81 | 1.05 | |

| North Line Deep Tunnel Pumping Station | 9.26 | 12 | 12 | 11.6 | 15 | |

| North of Baiyushan Qinghua Road | 0.62 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 2.3 | 3.0 | |

| Longwangzui (South Line) | / | / | / | 3.5 | 4.5 | |

| Design Capacity of Beihu Wastewater Treatment Plant | 9.26 | 12 | 12 | 11.6 | 11.6 | |

| Operating Condition | Erlangmiao-Third Ring Road | Third Ring Road-Wudong | Wudong-Pumping Station | Luobuzui-Third Ring Road | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q2 (m3/s) | Q3 (m3/s) | Q4 (m3/s) | Q5 (m3/s) | ||

| Near-term | Average Dry Season Flow | 5.67 | 7.97 | 8.37 | 2.3 |

| Peak Dry Season Flow | 7.37 | 10.37 | 10.89 | 3.0 | |

| Rainy Season Flow | 7.37 | 10.37 | 10.89 | 3.0 | |

| Long-term | Average Dry Season Flow | 6.37 | 10.77 | 11.6 | 4.4 |

| Peak Dry Season Flow | 8.28 | 14 | 15 | 5.72 | |

| No. | Project Name | Pretreatment Facilities and Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hong Kong Deep Sewage Tunnel Pretreatment Station | Coarse Bar Screen: 20 mm Fine Bar Screen: 4 mm Grit Chamber: Removes 95% of grit particles larger than 0.2 mm |

| 2 | Domestic Urban Wastewater Treatment Plants | Coarse Bar Screen: 20–25 mm Fine Bar Screen: 6 mm Grit Chamber: Removes 95% of grit particles larger than 0.2 mm |

| City/Project | Pretreatment/Preliminary Treatment | Shaft Design and Energy Dissipation | Intelligent Operation and Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hong Kong-HATS Stage 2A | Multi-stage bar screens and grit removal; grease separation; air venting for odor control; effluent delivered via deep tunnel to secondary treatment plant | Vortex-type drop shaft with air conduits and energy dissipation pool; vent shafts to prevent negative pressure [32] | Real-time monitoring and adaptive SCADA control, enabling multi-pump coordination and automated gas venting |

| Singapore-DTSS Phase 2 (Changi WRP) | Fully enclosed pretreatment units with high-efficiency swirl grit and grease removal; pre-membrane equalization tanks to buffer flow | Multi-stage swirl shaft with buffer chamber, ~90 m depth; optimized for energy dissipation and gas separation | AI-based predictive flow control; centralized operation platform coordinates all pumping stations for unattended operation [33] |

| London-Thames Tideway Tunnel | Multiple interception and storage shafts integrated with pretreatment; vortex and grit control measures at entry [34] | Vertical vortex-type shafts with energy dissipation chamber; vent shafts for air release; 60–70 m depth | Digital twin system for real-time hydraulic simulation, predictive maintenance, and AI-assisted emergency response |

| Chicago-TARP (Tunnel and Reservoir Plan) | Initial grit and storage function; captures combined sewer overflows for pumping to treatment plants | Baffle-type drop shafts; up to 90 m depth; retrofitted vortex sections to mitigate cavitation [10] | Real-time rainfall forecasting and pump station control; limited AI application |

| Tokyo-Edogawa Trunk Sewer | Rainwater and wastewater separation with grit removal; automated sediment cleaning; odor control [35] | Spiral vortex drop shaft with vent shaft; optimized for gas–liquid separation and wall erosion mitigation | Adaptive pump control with AI, IoT-based sediment prediction, and shaft monitoring |

| Wuhan-East Lake Deep Tunnel | Integrated pretreatment and online sediment removal, coupling pretreatment facilities with real-time cleaning to enhance operational efficiency | Multi-point coordinated shaft layout, optimizing shaft positioning and pump station coordination for improved emergency response | Intelligent operation and control system: real-time flow and pump monitoring, automated sediment cleaning, adaptive pump operation, and optimized gas venting |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, D.; Wang, T.; Wu, X. Model-Driven Sewage System Design and Intelligent Management of the Wuhan East Lake Deep Tunnel Drainage Project. Water 2025, 17, 3091. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17213091

Jin D, Wang T, Wu X. Model-Driven Sewage System Design and Intelligent Management of the Wuhan East Lake Deep Tunnel Drainage Project. Water. 2025; 17(21):3091. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17213091

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Deqing, Tao Wang, and Xianming Wu. 2025. "Model-Driven Sewage System Design and Intelligent Management of the Wuhan East Lake Deep Tunnel Drainage Project" Water 17, no. 21: 3091. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17213091

APA StyleJin, D., Wang, T., & Wu, X. (2025). Model-Driven Sewage System Design and Intelligent Management of the Wuhan East Lake Deep Tunnel Drainage Project. Water, 17(21), 3091. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17213091