1. Introduction

Water scarcity poses a significant constraint to sustainable development in the arid and semi-arid regions of northern China [

1]. Understanding the relationship between water consumption and economic growth is crucial for effective resource management. Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, a key energy base and ecological barrier for northern China, exemplifies these challenges. Its role as an “ecological barrier” is primarily to combat desertification and preserve grassland ecosystems, thereby mitigating sandstorms and protecting water sources for downstream regions like the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei area against pressures from climate change and unsustainable land use [

2,

3]. In recent years, with ecological civilization rising as a national priority in China [

4], the link between water resources and economic growth has attracted increasing attention. This is especially true in the arid and semi-arid regions of northern China, where water scarcity constrains sustainable development. Although few systematic studies focused exclusively on Inner Mongolia, some useful insights can be drawn from the research on the Yellow River Basin, the broader northwest region, and national-level analyses.

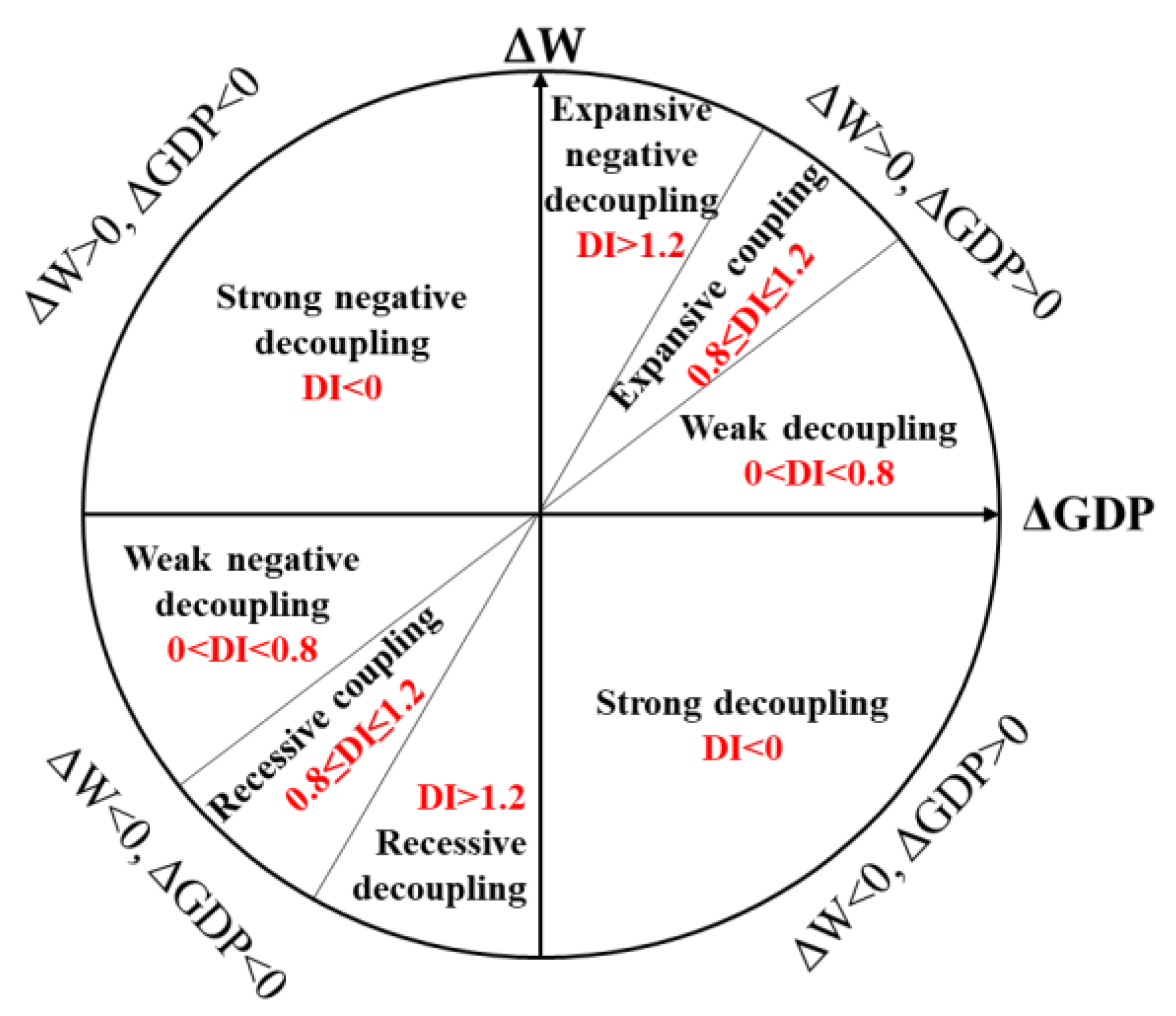

Most current studies use a “decoupling” framework—such as the Tapio model [

5], ecological footprint method [

6], or decomposition analysis [

7]—to examine the relationship between water consumption and economic development. Evidence indicates that China overall, along with key regions like the Yangtze River Economic Belt and the Yellow River Basin, is gradually transitioning from “expansive coupling” or “weak decoupling” toward “strong decoupling” [

1,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. This shift implies that economic growth is becoming less reliant on water consumption. For Inner Mongolia, a resource-dependent region with large fossil fuel energy and agricultural sectors, this trend offers a valuable reference. However, high water intensity in industry and farming makes achieving strong decoupling difficult [

11].

Located in the upper reaches of the Yellow River Basin, Inner Mongolia serves as both an ecological barrier and a major water consumer. Therefore, studies focused on the basin are directly applicable [

9,

12,

13]. For example, Meng et al. [

12] emphasized how industrial restructuring and technological advances enhance water efficiency. Xue [

13] underscored the importance of coordinated water and land management across regions. Li et al. [

9] identified technology, structure, and scale as key drivers affecting water demand differently. Collectively, these studies suggest a common trajectory: early economic growth often increases water use, but over time, structural shifts and innovation can improve efficiency and help align water use with economic development. These patterns closely reflect the challenges faced by Inner Mongolia.

Recent studies have highlighted the complex interplay between water consumption and socioeconomic development across different scales and contexts. At the national and regional levels in China, Wang et al. [

14] found that economic growth and water use are increasingly decoupling, though patterns vary significantly between provinces, reflecting disparities in industrial structure and policy effectiveness. In Thailand, Sasipha et al. [

15] identified income, urbanization, and policy interventions as key drivers of water consumption, emphasizing the role of institutional frameworks in promoting sustainable use. At the household level, Dieu-Hang et al. [

16] showed that public awareness, eco-labeling, and pro-environmental attitudes strongly influence the adoption of water-efficient technologies in OECD countries. Extending to cross-national comparisons, Marcos et al. [

17] revealed persistent inequalities in water use among EU countries, linked to economic disparities and differing sustainability priorities. Meanwhile, Flörke et al. [

18] demonstrated through long-term global simulations that shifts in domestic and industrial water use over the past six decades closely mirror broader socioeconomic transformations, underscoring water as a sensitive indicator of development trajectories.

Regional studies in China highlight that water use and economic growth are increasingly intertwined but rarely on a sustainable path. In the Loess and Yellow River basins, efficiency gains improve ecological resilience, yet progress remains uneven across regions [

19,

20]. Water constraints are already slowing growth in the Yangtze River Belt [

21], while in Shaanxi and Anhui, weak decoupling or learning effects suggest only gradual improvements [

22,

23]. Heilongjiang’s nonlinear dynamics reveal that structural inertia delays water savings [

24], and resource-dependent regions like those studied by He et al. [

25] show that industrial transformation is key to cutting water intensity. Overall, while some areas approach peak water use, the evidence—such as the mixed EKC results [

26]—shows that growth alone will not solve the problem: deliberate policy and structural changes are essential. Other studies highlight regional variations in water–economy dynamics. Wang and Wang [

27] demonstrated that inequality in water consumption across China is easily influenced by economic patterns and policy, and Gao et al. [

28] revealed sharp urban–rural disparities in water consumption within the northwest of China.

The above-mentioned findings are particularly relevant for Inner Mongolia, which is geographically vast and internally diverse: the east relies heavily on agriculture, the central region on energy industries, and the west struggles with ecological water shortages. Overlooking these internal differences may lead to one-size-fits-all policies that prove ineffective in practice. In summary, while existing studies provide useful methodologies and reveal broader trends [

1,

12,

27], most studies operated at a national or basin-wide scale. Given Inner Mongolia’s unique resource endowment, industrial structure, and regional variations, these findings cannot fully explain its local water-growth dynamics—particularly in sectors like agriculture, herding, and the transition of resource-intensive economies. There is a clear need for targeted, differentiated research that can uncover the region’s specific water constraints and identify effective response strategies, thereby helping to balance ecological protection with high-quality development. This study aims to fill this gap by applying the Tapio decoupling model to analyze the spatiotemporal decoupling relationship between water consumption and economic growth in Inner Mongolia and its twelve leagues/cities from 2004 to 2023, identifying regional patterns, driving mechanisms, and targeted policy implications.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Economic GDP and Water Consumption in Inner Mongolia

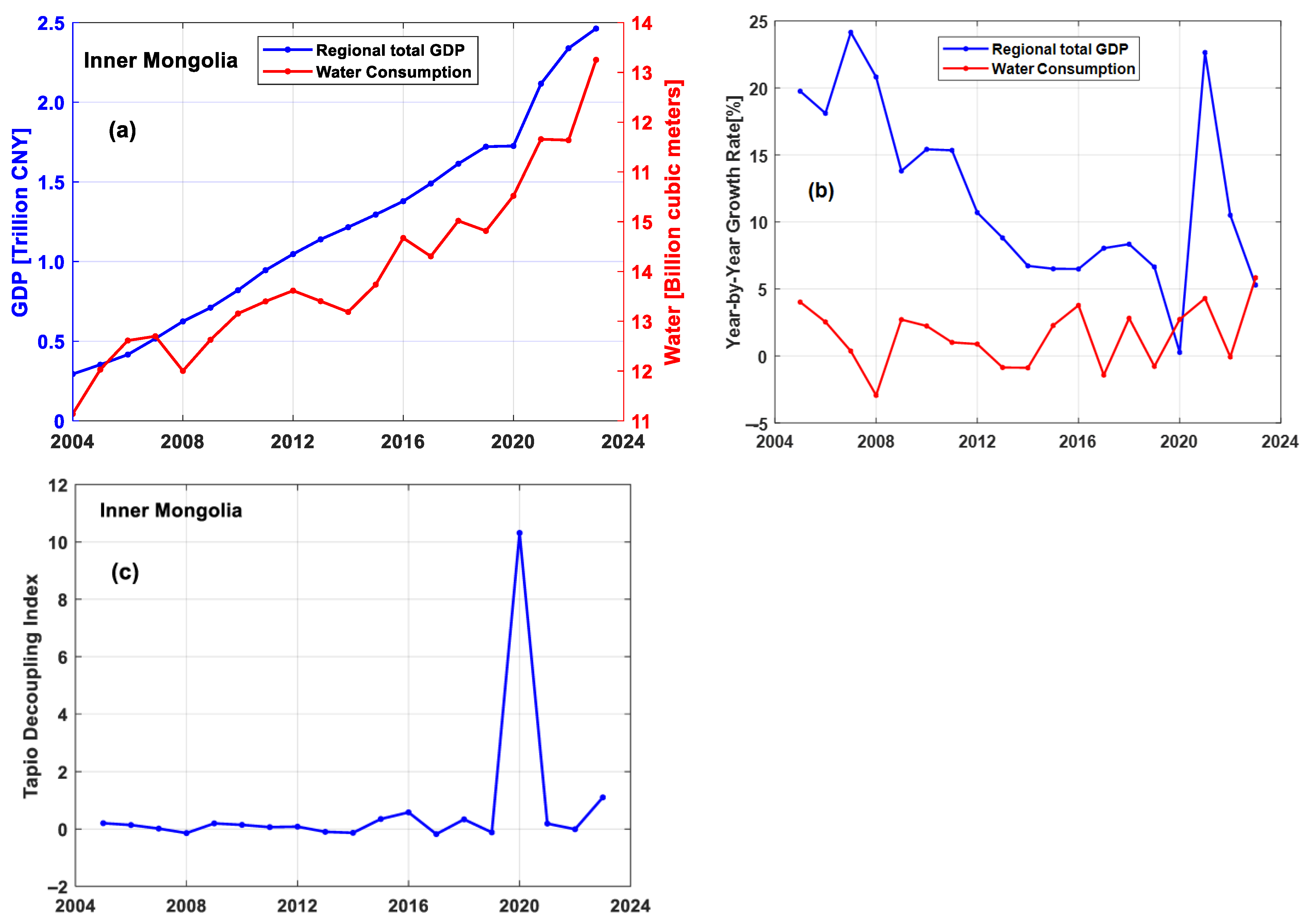

Figure 3 shows the regional GDP of Inner Mongolia from 2004 to 2023, which registered an approximately eightfold increase from CNY 294.235 billion to CNY 2462.696 billion. During the same period, water consumption rose from 11.07 billion cubic meters to 14.626 billion cubic meters. A general positive correlation between economic output and water use is observable over these two decades. To further investigate this relationship, we calculated the annual growth rates of both variables. The results indicate that, except for 2020, the GDP growth rate significantly exceeded that of water consumption in every year. The outlier in 2020 was primarily due to the 2020–2021 pandemic, which caused a substantial economic shock early that year.

Additionally, a decoupling index (DI) between GDP and water consumption was calculated for Inner Mongolia based on Equation (1). The results show that for most years, the DI ranged from −0.14 to 0.80, reflecting weak decoupling or weak negative decoupling in 11 years and strong decoupling in 6 years. Notably, the pandemic led to a DI value of 10.31 for 2020–2021, with ΔW > 0 and ΔGDP > 0, indicating expansive negative decoupling. For 2022–2023, the decoupling index was 1.10 (below 1.20), also with ΔW > 0 and ΔGDP > 0, suggesting a growth-connected phase. Overall, the decoupling state between water consumption and economic growth in Inner Mongolia is gradually shifting from “weak decoupling” to “strong decoupling,” reflecting improved water use efficiency and a decreasing dependency of economic growth on water resources. The specific Tapio DI can be seen in

Table A1.

3.2. Regional Disparities in GDP and Water Consumption Across Inner Mongolia

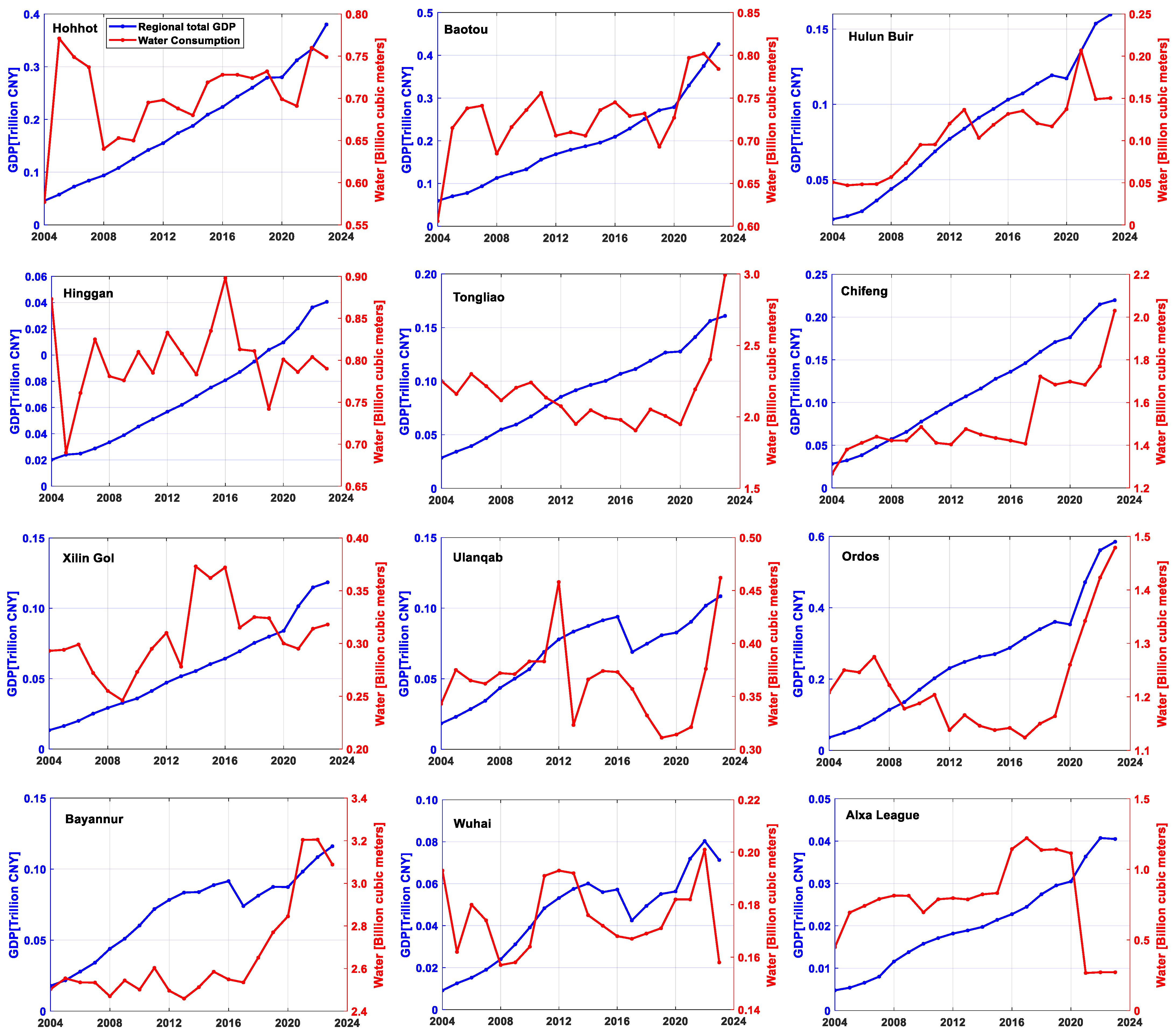

Figure 4 shows the GDP and water consumption trends across administrative divisions within the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. Overall, most regions experienced economic growth, reflecting improved levels of development. Water consumption, however, varied noticeably among different areas. For instance, in industrially advanced cities such as Ordos and Baotou, significant GDP growth did not lead to a parallel rise in water use. Instead, water consumption in some years remained stable or even decreased, which is likely attributable to local government promotion of water conservation measures and adjustments in industrial structure.

Generally, all 12 cities showed upward trends in GDP, while changes in water consumption followed three distinct patterns:

Strong growth type: Cities like Ordos (energy-oriented) and Hohhot (upgraded service sector) saw rapid GDP growth accompanied by a slower rise in water use.

Fluctuation type: In regions such as Bayannur and Chifeng (dominated by agriculture and animal husbandry), water consumption varied significantly, influenced by climate conditions and cropping patterns.

Stability type: Areas including Wuhai (where industrial water-saving technologies were applied) and Alxa League (subject to ecological constraints) maintained stable water consumption alongside moderate GDP growth.

Decoupling analysis further reveals that in industrial cities like Ordos and Baotou, steep GDP growth contrasted with gentle increases in water use, underscoring the water-saving effects of technological progress and industrial upgrading. In agricultural regions such as Tongliao and Hinggan League, intermittent overlapping of the two curves reflects ongoing reliance on irrigation that has yet to be fully addressed.

As summarized in

Table 1, the decoupling index (DI) between water consumption and economic growth was calculated for Inner Mongolia and its administrative divisions from 2004 to 2023 using the Tapio model. The DI values correspond to categories such as weak decoupling, strong decoupling, and expansive negative decoupling (refer to

Figure 2 for definitions). The results show that Inner Mongolia as a whole was mostly in a state of weak decoupling or weak negative decoupling during most years, with occasional strong decoupling in certain periods and regions. For example, between 2015 and 2016, cities including Hohhot and Baotou achieved strong decoupling, indicating an effective reduction in water use alongside economic expansion. The specific analysis results are as follows.

- (a)

The decoupling status in Inner Mongolia exhibits significant spatial differentiation

The industrial-dominated regions (e.g., Ordos, Baotou, Wuhai) exhibited a high frequency of strong decoupling (DI < 0), particularly after 2010, a period marked by technological innovations such as water-saving retrofits in the coal chemical industry, although exceptions did occur—for instance, Baotou showed expansive negative decoupling in 2007–2008 (DI = −0.37). In contrast, agricultural and pastoral regions (e.g., Bayannur, Tongliao, Chifeng) were predominantly characterized by weak negative decoupling (0 < DI < 0.8), reflecting constraints posed by rigid agricultural water demand. A notable example is Bayannur, where the DI reached −23.46 in 2019–2020, highlighting acute vulnerability to climate conditions and inefficient irrigation. Meanwhile, ecologically vulnerable areas (e.g., Alxa, Xilin Gol) showed significant DI fluctuations, often triggered by policy interventions. For example, eco-relocation efforts in 2004–2005 led to a sharp economic decline and an abnormal DI value of 4.25.

- (b)

Impact of Major Events on Decoupling Dynamics

During the 2020–2021 pandemic, the collapse of the tourism industry triggered a sharp economic decline in some regions. However, the demand for living and ecological water—which is relatively inflexible—persisted, leading to strong negative decoupling in cities such as Hohhot (DI = −13.65) and Hulun Buir (DI = −10.00). By contrast, Ordos, which maintained a stable energy supply, recorded a DI of −4.17, underscoring varying levels of resilience across different industrial structures. The stark difference between the DI for the entire region (10.31) and individual cities (ranging from −23.46 to 2.91) during 2019–2020 is primarily due to the aggregate effect. The regional DI is calculated based on total regional water use and GDP, which can mask the extreme variations occurring at the city level, where some experienced severe economic contraction with relatively stable water use (leading to highly negative DIs), while others had different dynamics. The pandemic’s impact was highly heterogeneous across sectors and geographies.

In the earlier policy intervention period—exemplified by the introduction of the “most stringent water resource management system” in 2014—certain leagues and cities shifted toward high-value-added livestock farming in response to the industrial water restrictions, which enabled them to achieve strong decoupling. Nevertheless, other regions continued to experience weak negative decoupling, largely due to delays in the adaptation of agricultural policies.

- (c)

Long-Term Trends in Decoupling Transformation

During the period of deepening positive decoupling (2015–2023), the increased frequency of negative DI values across most leagues and cities reflects the effectiveness of ongoing water-saving technology promotion and policy enforcement. That said, agricultural regions continue to face a conspicuous bottleneck: the imperative to increase grain production has not been well synchronized with the adoption of efficient irrigation practices, revealing persistent shortcomings in water management.

In summary, while the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region has made clear progress in water resource management, continued attention is needed to address regional disparities and specific challenges within the agricultural sector. Achieving a win-win scenario—where water use efficiency supports high-quality economic and social development—will require further targeted and integrated policies.

4. Discussion

The decoupling process between water resource consumption and economic growth varies significantly across regions, revealing a tripartite pattern: industrial advancement, agricultural lag, and ecological sensitivity. This interpretation directly reflects the patterns observed in our results. For instance, Ordos and Baotou have sustained local economic growth by importing water-intensive products—such as agricultural goods—without substantially increasing local water use, achieving what is known as “strong decoupling.” However, this approach has transferred considerable water pressure to exporting regions like Tongliao, highlighting the need for cross-regional compensation mechanisms.

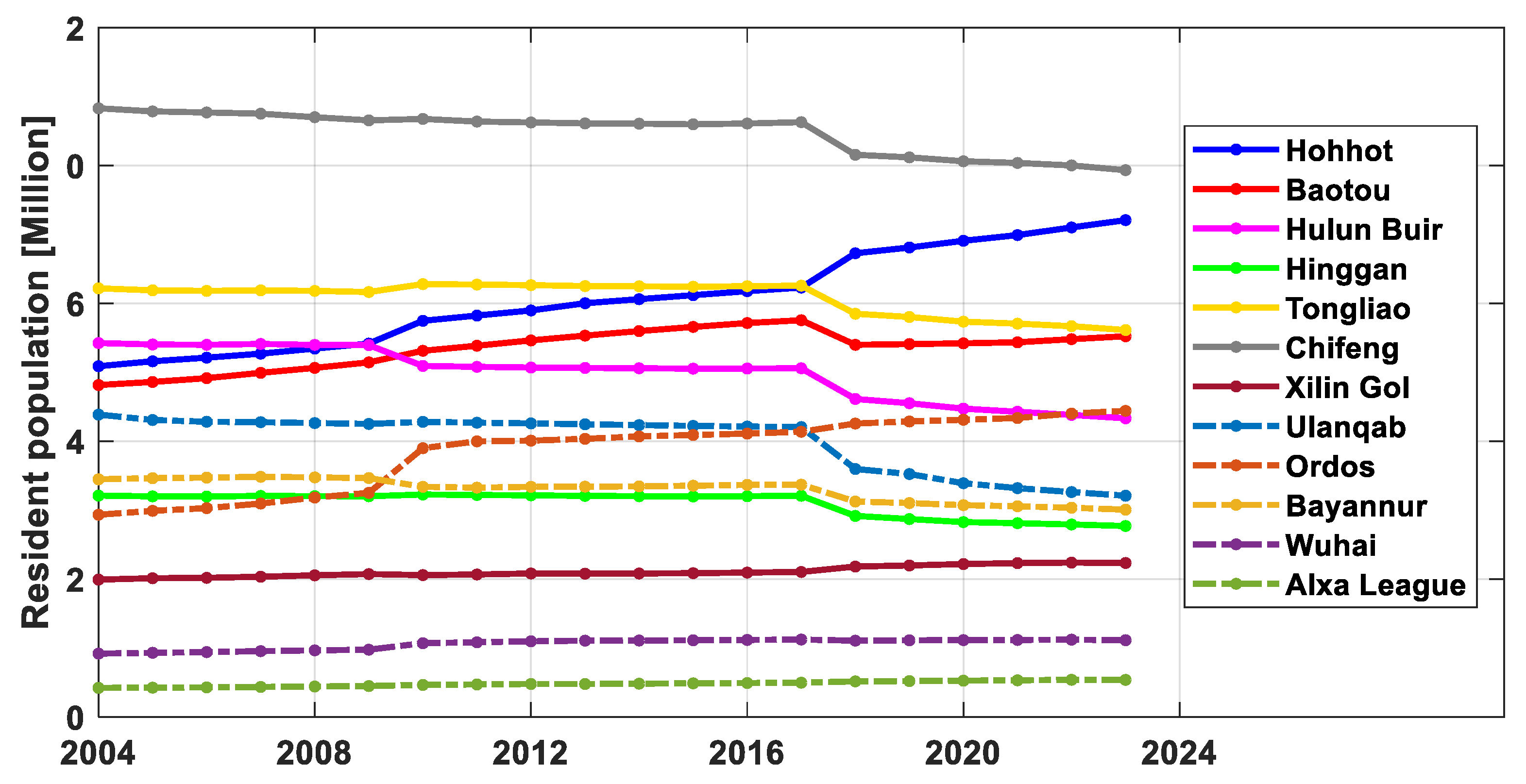

To further investigate the potential causes,

Figure 5 shows the resident population of twelve cities, and we can find that half of these twelve administrative divisions (Hulun Buir, Hinggan, Tongliao, Chifeng, Ulanqab and Bayannur) have a decreased resident population, as opposed to the other six cities.

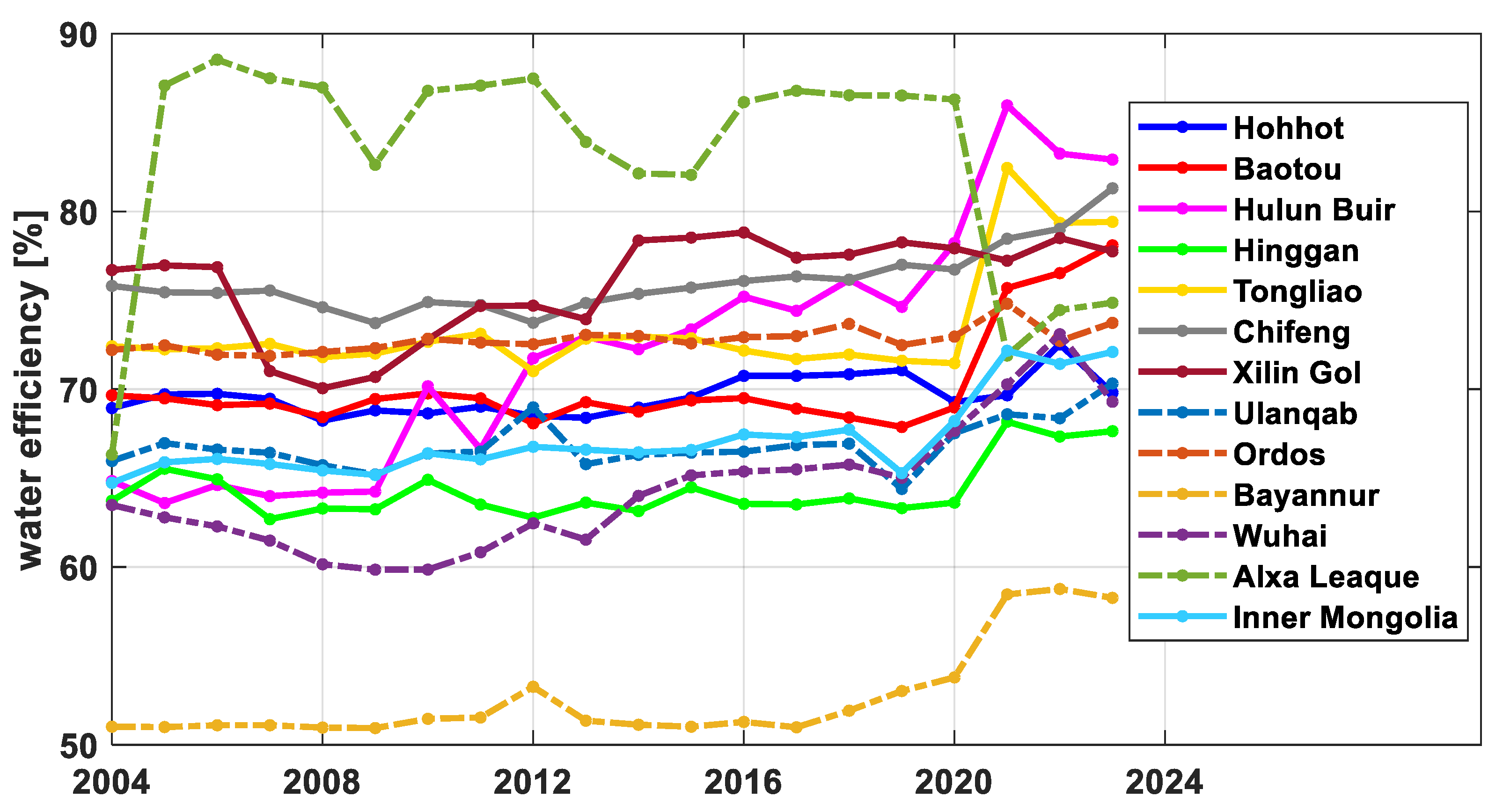

Figure 6 presents the water efficiency of Inner Mongolia and its twelve administrative divisions for the period from 2004 to 2023. For the entire Inner Mongolia region, the water efficiency increased from 64.73% (2004) to 72.10% (2023), especially notably since the year 2021, indicating that the adoption of water-saving technologies is beneficial to improve water efficiency and promote the decoupling procedure between the economy and water consumption. When it comes to water-saving technologies, the industrial sector has seen greater success due to its higher return on investment, as seen in Ordos’ coal chemical water recycling project. In contrast, adoption in agriculture remains slow—drip irrigation penetration in Bayannur, for example, remains below 30%, with the lowest water efficiency (below 60%), as can be confirmed by

Figure 6. To improve agricultural water efficiency, targeted subsidy policies appear essential.

Figure 7 shows the correlation coefficients between the resilient population and GDP and water consumption of Inner Mongolia and the twelve administrative divisions. The statistical results show that significant positive or negative correlations between population and GDP do not in fact mean that the resident population directly affects GDP growth. In some cases, population quality (human capital) is far more important than quantity. In addition, an increasing population will definitely increase the water consumption, especially for domestic water. However, water consumption is mainly made up of three contributors: domestic, agricultural and industrial water. Therefore, the use of GDP in the DI calculation incorporates economic output but does not directly incorporate some factors such as population (

Figure 7). However, since economic structure influences both GDP and water use, the DI effectively indicates how efficiently a region’s economic output is generated relative to its water consumption. A negative DI in industrialized regions may suggest that water-saving technologies contribute more to the decoupling of growth from use, while a positive DI in agricultural regions indicates water-intensive production. This does not inherently “praise” or “underscore” any region but reveals their economic–water nexus, crucial for targeted policy.

Financial innovation also plays a key role in water conservation. The “water-saving loan” initiative in Baotou and Hohhot, which raised CNY 2.7 billion, helped achieve a negative DI between 2018 and 2019. This loan program provided preferential financing for enterprises to implement water-saving technological transformations, directly reducing their water intake and consumption per unit of output. Nevertheless, policy coverage remains uneven—areas like Wuhai and Alxa League have seen limited inclusion and would benefit from expanded support.

These policy impacts and limitations are reflected in, and help to explain, the distinct regional patterns observed in the data. For example, regarding

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, region Bayannur has a declining resident population (

Figure 5) but persistently low water efficiency (below 60%,

Figure 6), which can be interpreted as reflecting structural rigidity in agricultural water use—where outmigration does not necessarily reduce irrigation demand due to fixed cropping patterns and slow adoption of water-saving technologies. In contrast, region Ordos shows a growing population alongside rising water efficiency (exceeding 73% by 2023), indicating that industrial upgrading and technological innovation have effectively decoupled economic growth from water consumption, despite demographic expansion. Meanwhile, Alxa League maintains a stable population but exhibits volatile water efficiency (

Figure 6), suggesting that ecological policies cause short-term fluctuations in water use without establishing long-term sustainable mechanisms.

Beyond the broad agricultural–industrial divide, further distinctions emerge when comparing other typologies. The industrial city of Wuhai, for instance, demonstrates an increased high water efficiency since 2020 (

Figure 6) despite a small and stable population (

Figure 5), underscoring the decisive role of advanced water-saving technologies and industrial restructuring (e.g., in coal–chemical sectors) in achieving decoupling. Conversely, in Xilin Gol League, significant population loss (

Figure 5) coincides with only moderate gains in water efficiency, revealing that policy-driven ecological restoration (e.g., grazing bans) without concomitant industrial transformation fails to secure lasting decoupling. Additionally, the cases of Hohhot and Baotou highlight how targeted financial instruments (e.g., “water-saving loans”) can amplify the benefits of existing industrial advantages, enabling these regions to maintain robust economic growth while curbing absolute water use.

The case of Xilin Gol underscores a broader theme: the fragility of decoupling driven primarily by administrative ecological measures. Ecological compensation measures can induce short-term decoupling, as seen in Xilin Gol during the grazing ban policy, when DI reached 4.76. However, without robust industrial development to follow, gains may reverse—DI later fell to 0.40 in 2022–2023. Thus, ecological measures should be coupled with livelihood transition support to ensure sustained decoupling.

Beyond socioeconomic drivers, extreme climate events further stress water management systems and can abruptly disrupt decoupling trends. The extreme drought events further stress water management systems. The severe drought in Bayannur’s Hetao irrigation district (2019–2020) caused DI to plunge to −23.46, exposing vulnerabilities in water infrastructure under climate extremes. At the same time, water-rich regions are not immune to inefficiency: although Hulun Buir holds 60% of the region’s water resources, water-intensive industries like paper manufacturing have led to significant waste. Between 2011 and 2012, DI in the region rose to 2.14, indicating expansive negative decoupling—a reminder that abundant water does not justify wasteful practices.

In summary, the core challenge has shifted from absolute scarcity to structural issues. Agriculture must overcome bottlenecks in technology adoption, scaling, and cost-effectiveness (“technology–scale–benefit”); industry should enhance virtual water accounting and green finance tools; and vulnerable ecosystems require integrated policies that balance water conservation, economic development, and livelihood security (“water–economy–livelihood”). Future studies should combine virtual water flow analysis, climate scenario modeling, and industrial linkage assessments to enable targeted governance. Moreover, using the Tapio decoupling index to monitor abnormal DI fluctuations—especially in agricultural and ecologically sensitive regions—could support early warning and improved policy design, ultimately aligning water efficiency with high-quality regional development.

5. Conclusions

The decoupling relationship between water resources and economic growth in Inner Mongolia exhibits a distinct tripartite pattern: industrial-leading regions show advanced performance, agricultural regions lag behind, and ecologically vulnerable zones display high sensitivity. Studies indicate that industrially advanced areas, such as Ordos and Baotou, have achieved strong decoupling between economic growth and water consumption through improvements in water-saving technology and industrial restructuring—over the past two decades, around 60% of their DI values have been negative. Nevertheless, during phases of intensive industrial expansion, these regions still experience a rebound in water resource pressure, as seen in Ordos, where the DI fell to −4.17 in 2019–2020.

In agricultural and pastoral regions like Tongliao and Bayannur, the decoupling process is significantly delayed, constrained by inflexible irrigation needs and climate variability. Here, the conflict between grain production targets and the adoption of water-saving technologies is especially apparent—for instance, Tongliao’s DI jumped to 8.14 in 2022–2023. The ecologically vulnerable areas, including Alxa and Xilin Gol, show large fluctuations in decoupling status. Short-term policy measures can produce quick results but often lack long-term sustainability. The grazing ban in Xilin Gol, for example, pushed the DI to 4.76 in 2013–2014, but due to inadequate follow-up support for livelihood transitions, the DI dropped back to 0.40 by 2022–2023.

At the policy level, instruments such as the “Four Waters and Four Determinations” system and innovative financial mechanisms (e.g., “water-saving loans” totaling CNY 2.7 billion) have enhanced water efficiency in industrial sectors. However, agricultural water-saving remains hampered by fragmented operations and the low adoption of efficient technologies—drip irrigation penetration in Bayannur remains below 30%. Differentiated subsidy policies are needed to overcome the “technology–scale–benefit” bottleneck. Moreover, the implicit transfer of water pressure through virtual water trade—where Ordos’ strong decoupling partly depends on agricultural imports from water-stressed regions like Tongliao—underscores the urgency of establishing cross-regional ecological compensation mechanisms.

Looking ahead, water governance should consider virtual water flow analysis, climate modeling (e.g., drought early warning in the Hetao irrigation district), and industrial linkage assessments to form a region-specific policy framework. Priority should be given to enhancing water resilience in agricultural and ecologically sensitive areas, fostering the coordinated advancement of water security, economic development, and livelihood sustainability.