Biosorption of Iron-Contaminated Surface Waters Using Tinospora cordifolia Biomass: Insights from the Gostani Velpuru Canal, India

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Location

2.2. Water Sampling and Analysis

2.3. Collection and Preparation of T. cordifolia Biomass

- Powdered Biomass (PB): Fresh T. cordifolia stems were cut into small pieces and dried at 65 °C for 6 h [16,21], with a total weight of 600 g. They were combined with 2400 mL of water (four times the weight of the stems) in a beaker, filtered, and allowed to settle [37,38]. The residual component after desiccation, which was creamish brown in colour with a characteristic odour, was collected [31].

2.4. Detection Method of Iron

2.5. Control Conditions and Reagent Requirements for Iron Detection

2.6. Removal Efficiency Calculation of T. Cordifolia Biomass

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Diurnal Variation in Concentration of Iron at All Hotspot Locations on GVC

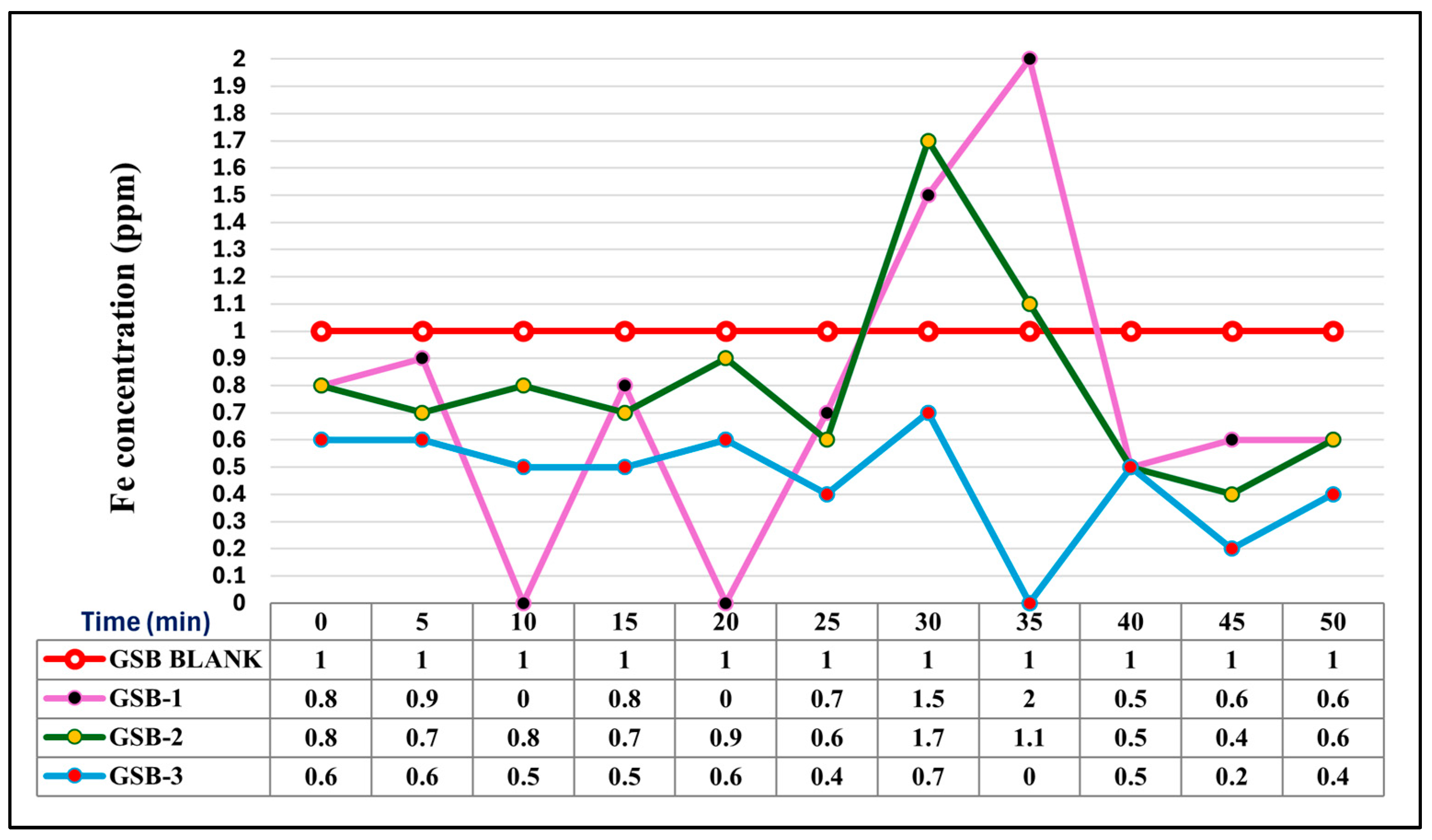

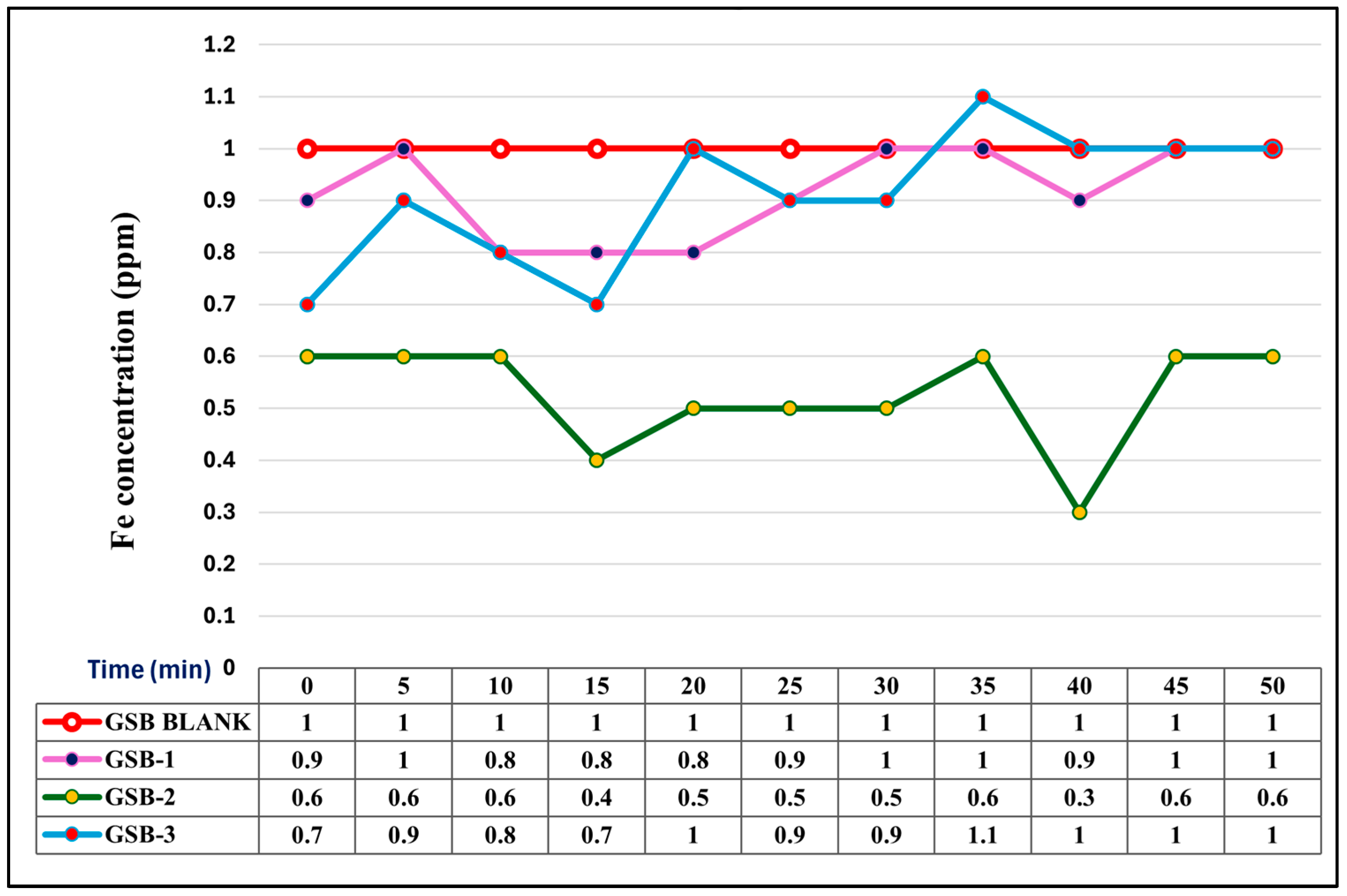

3.2. Comparative Iron Removal Efficiency: Static vs. Agitated Green Stem Biomass

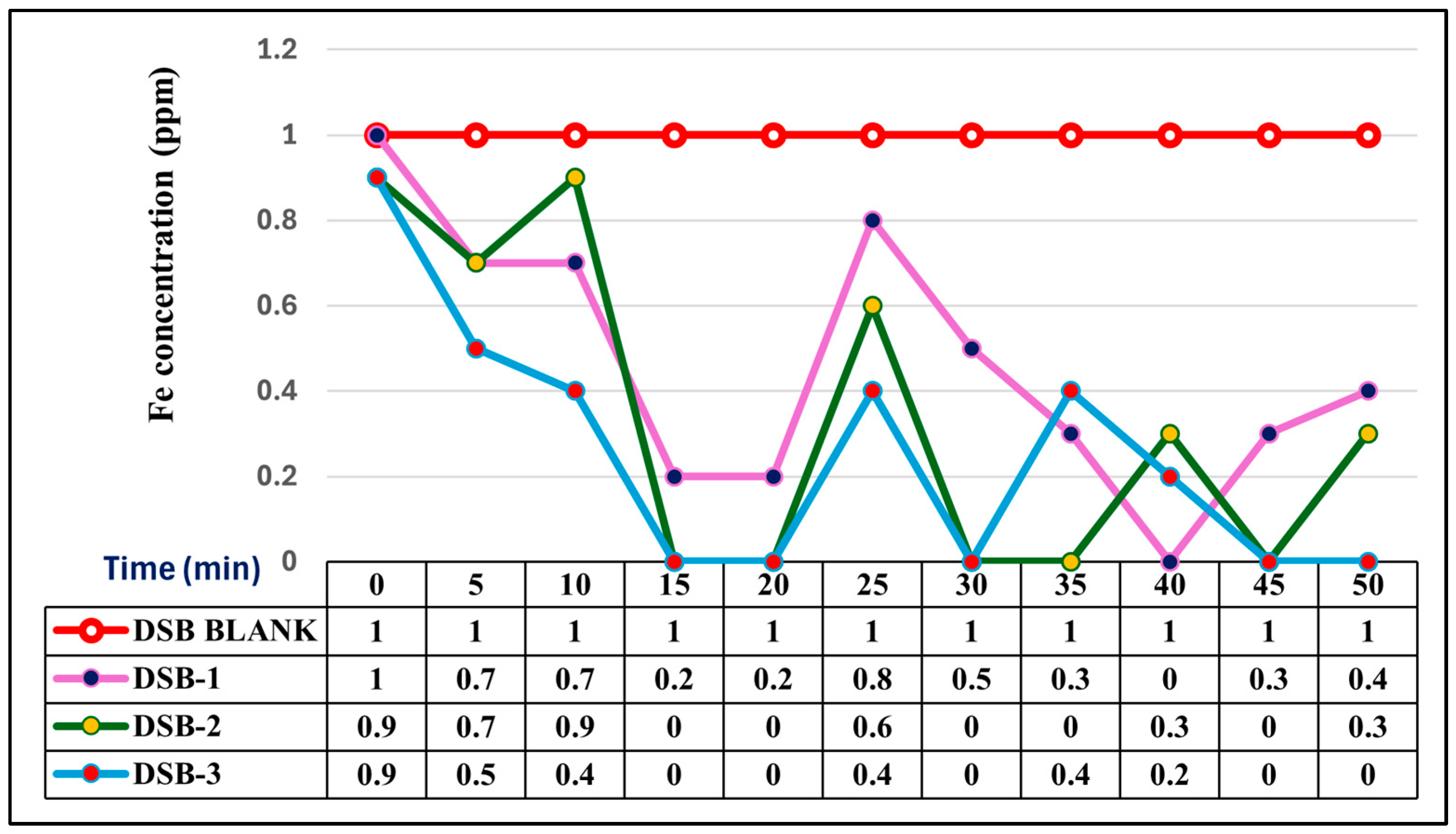

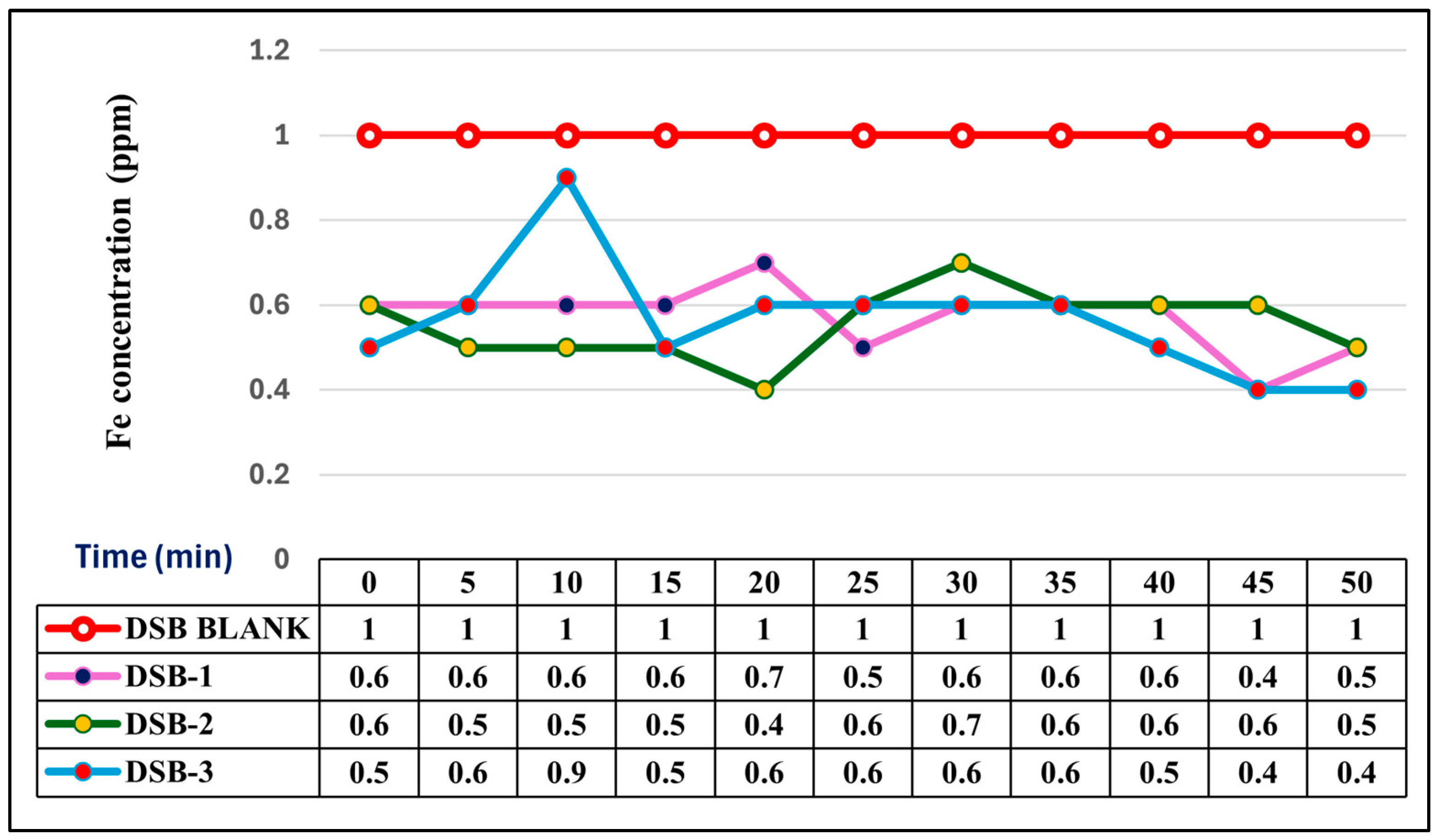

3.3. Comparative Iron Removal Efficiency: Static vs. Agitated Dry Stem Biomass

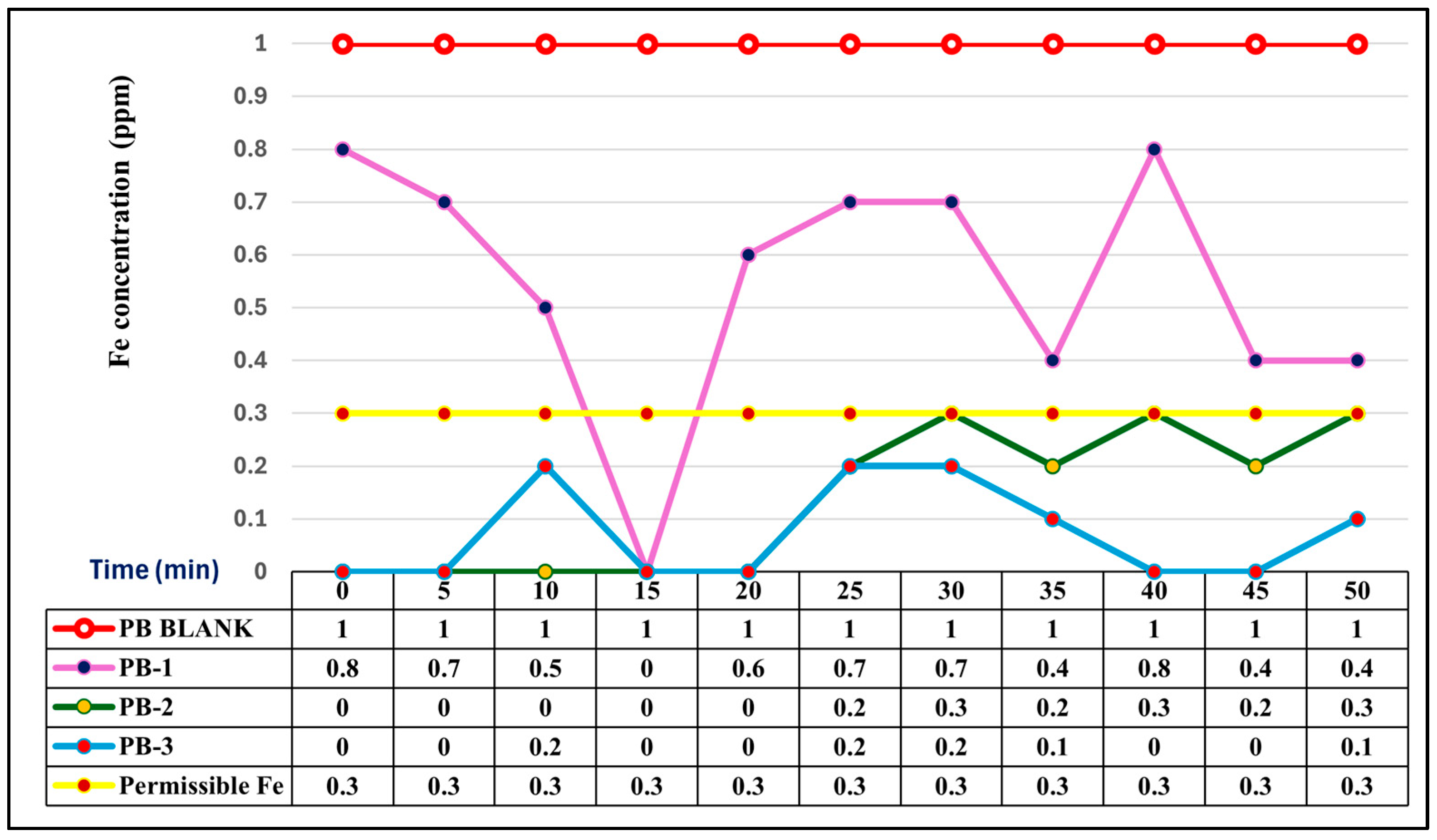

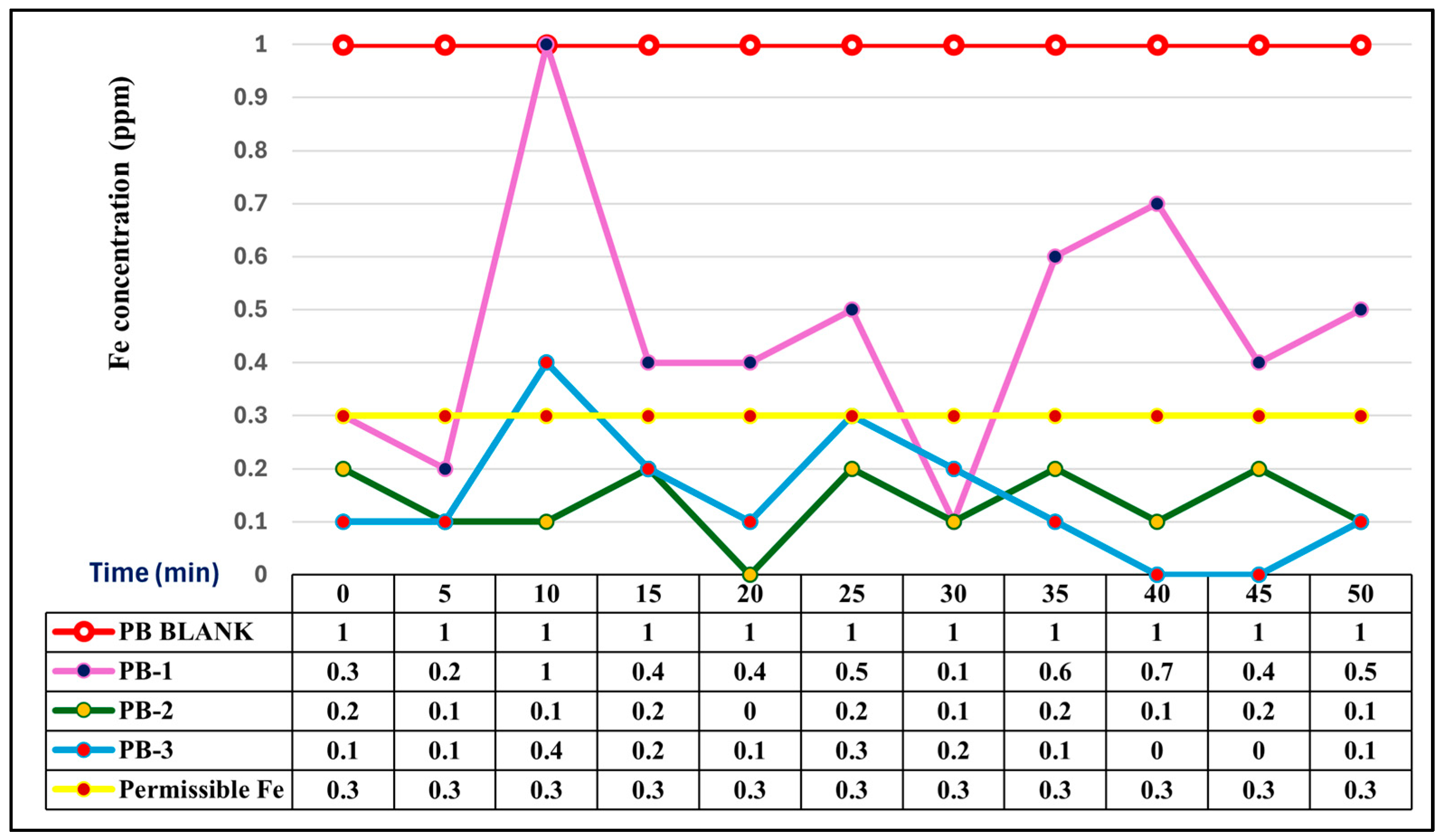

3.4. Comparative Iron Removal Efficiency: Static vs. Agitated Powder Biomass

3.5. Equilibrium Times of T. cordifolia Biomass

3.6. Diurnal Variation in Iron Removal Efficiency of Optimized T. cordifolia Biomass Combinations for Sustainable Surface Water Treatment

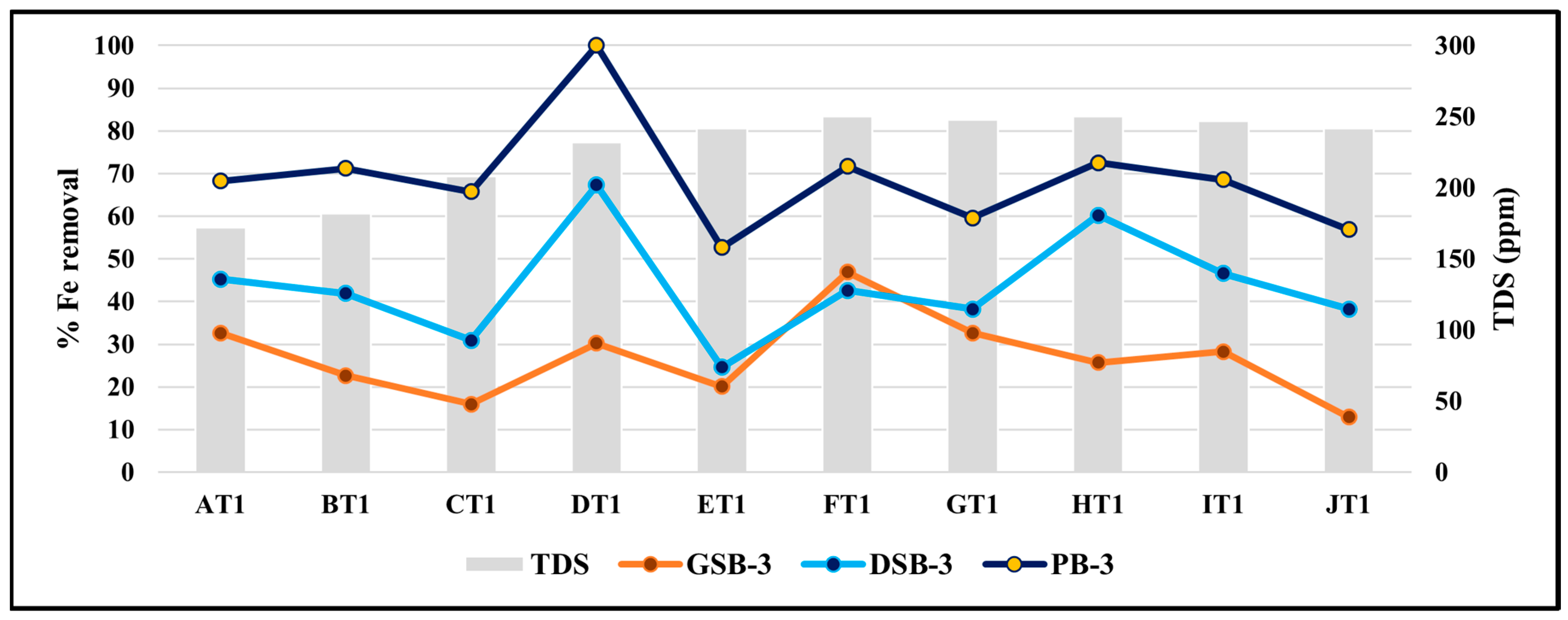

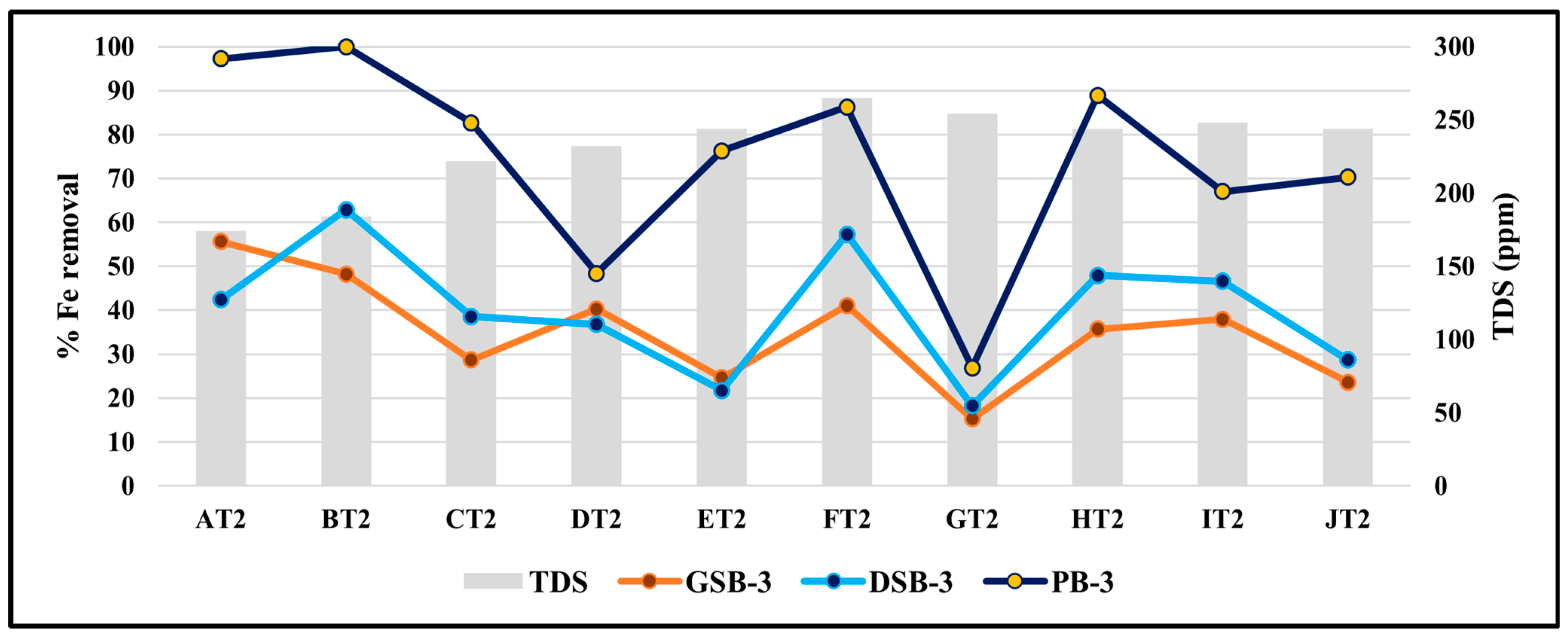

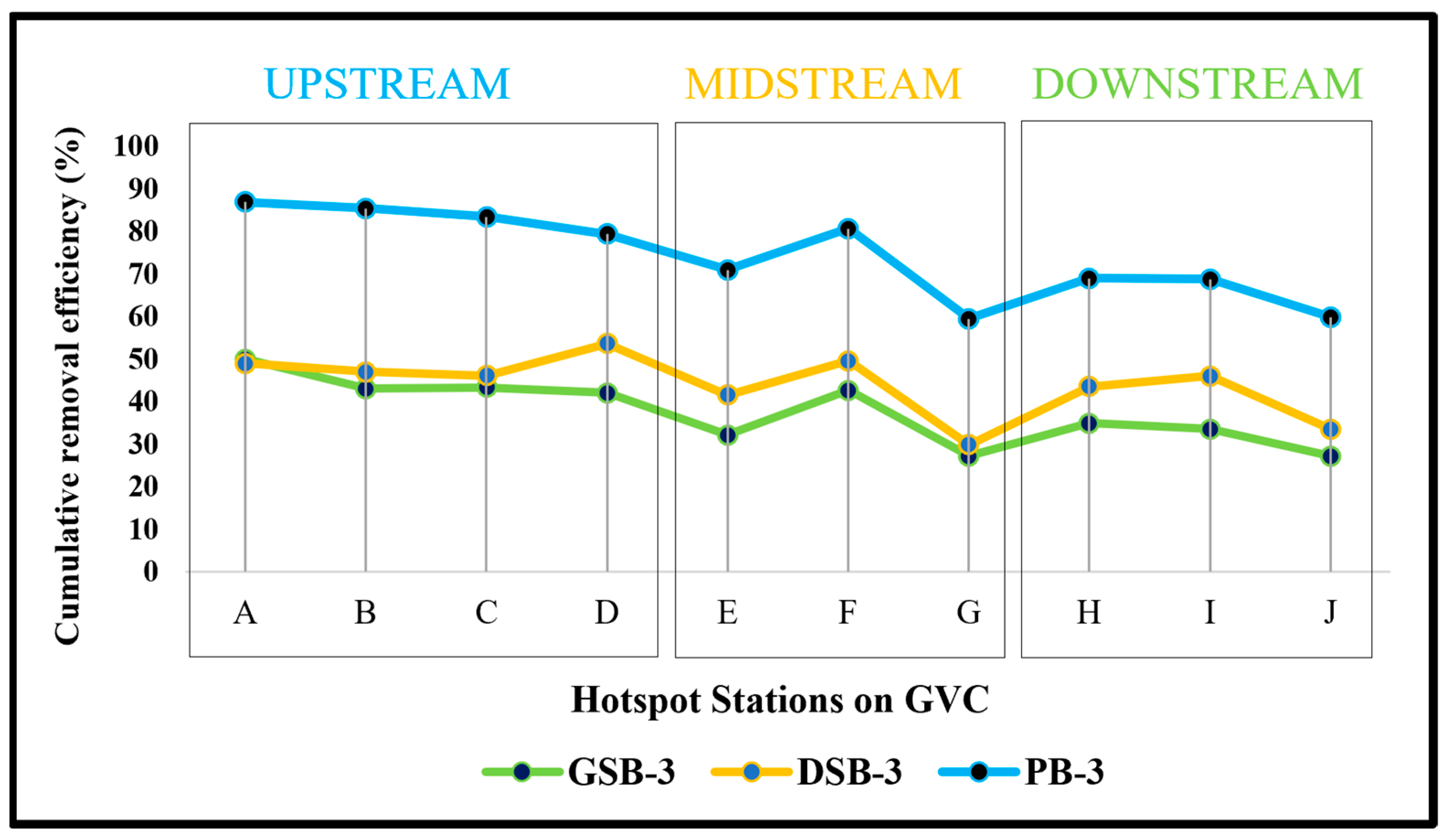

3.7. Cumulative Removal Efficiency of Iron by T. cordifolia Biomass at Upstream, Midstream and Downstream Diurnal Samples on GVC

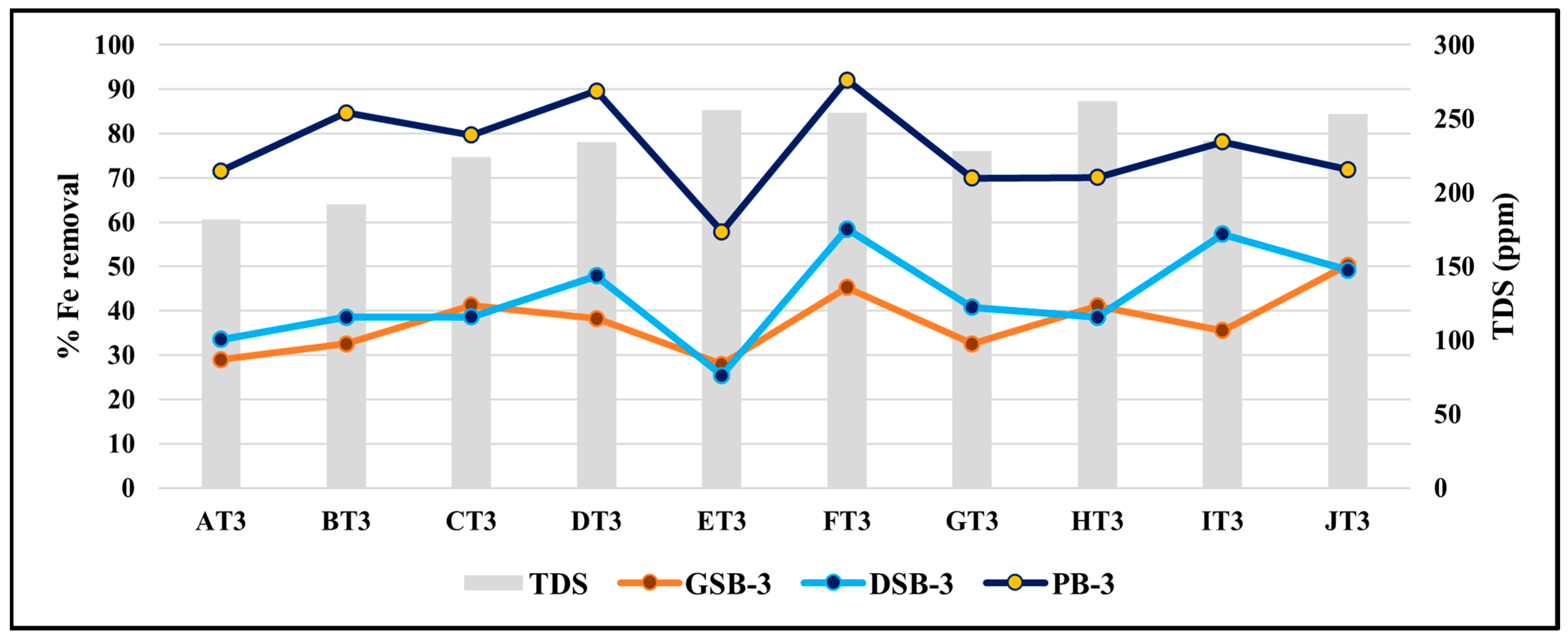

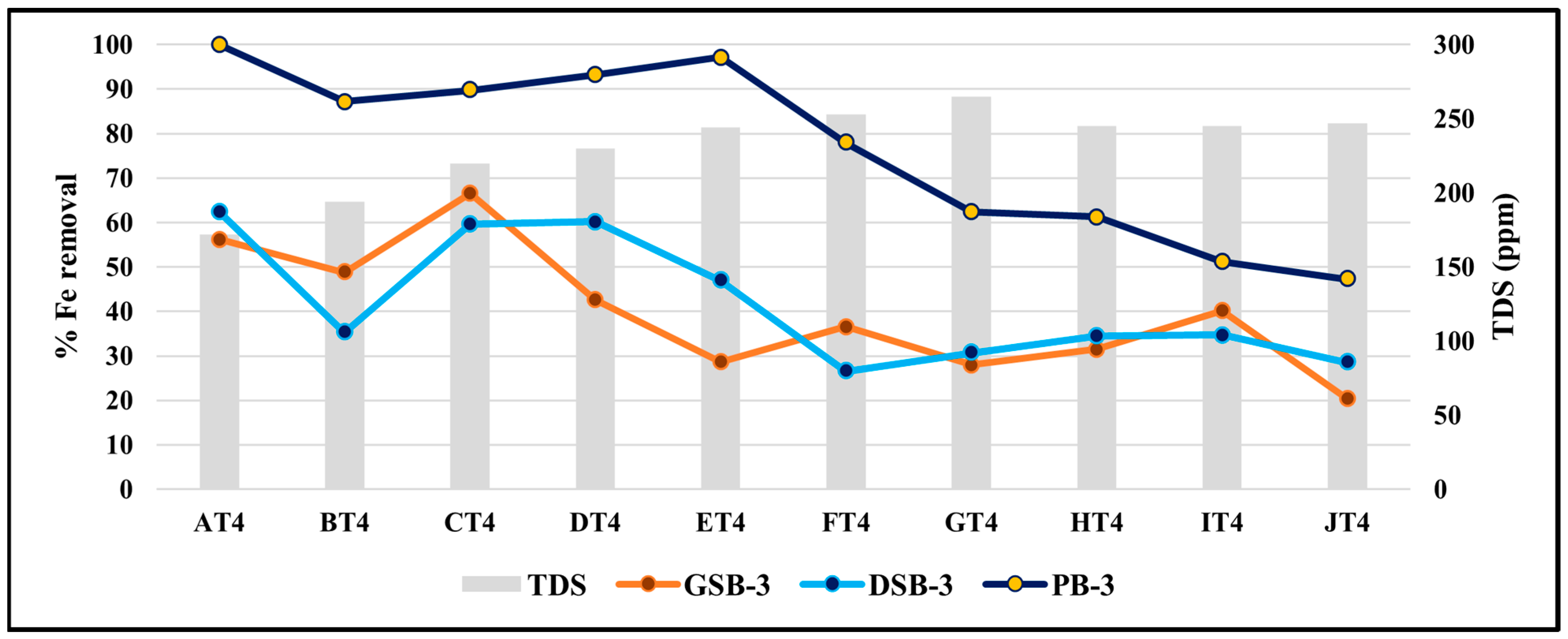

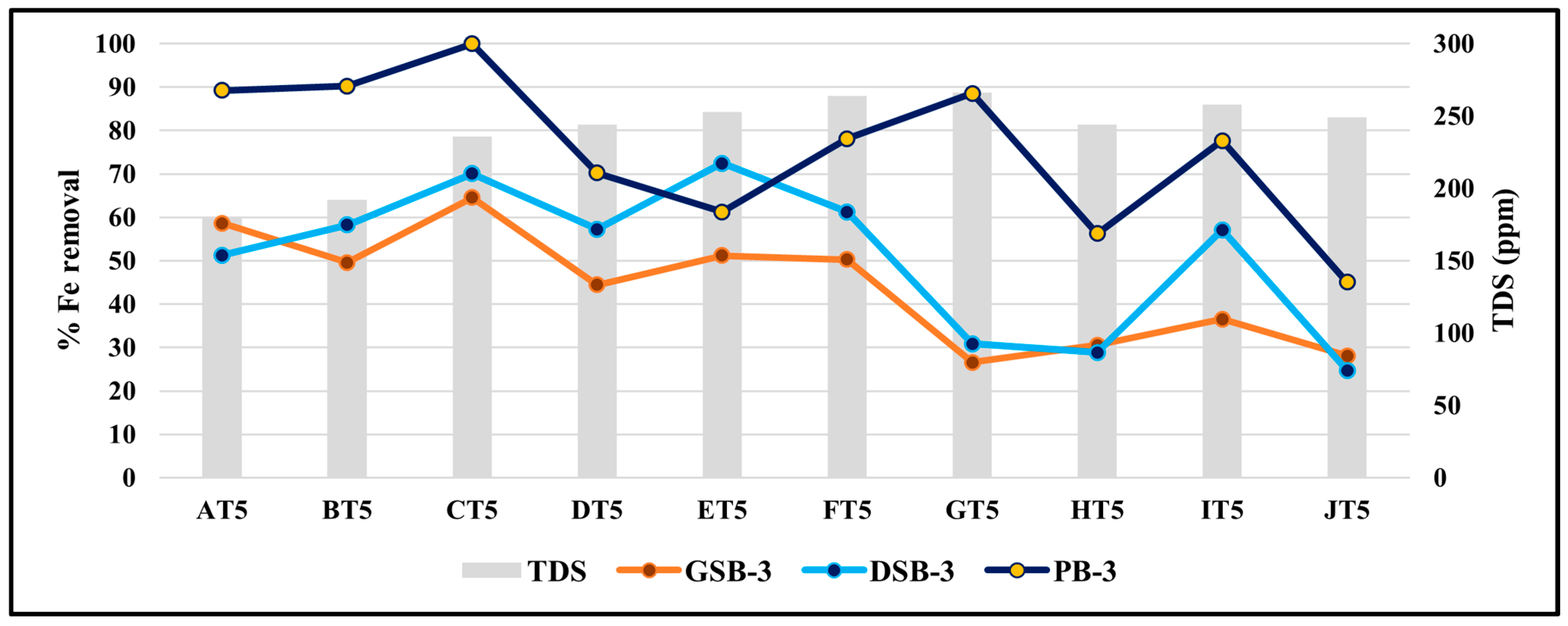

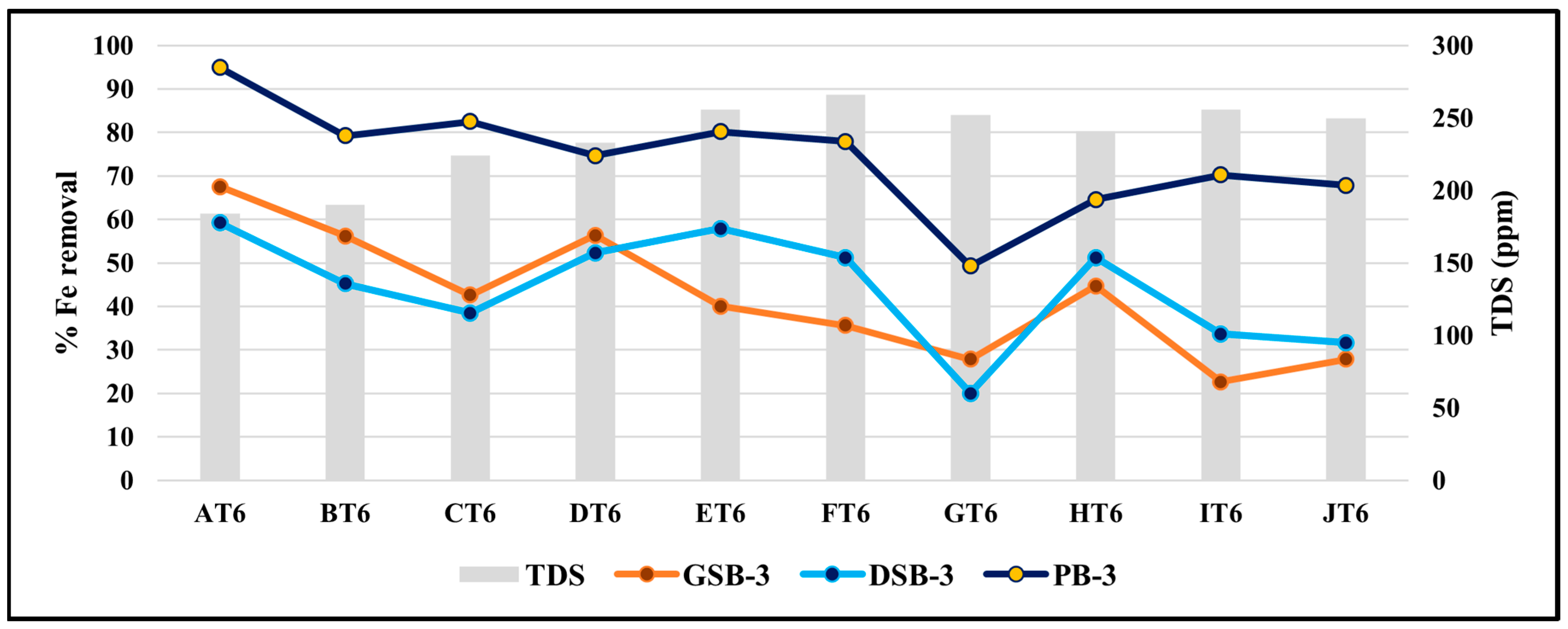

3.8. Effect of TDS on the Removal Efficiency of Iron

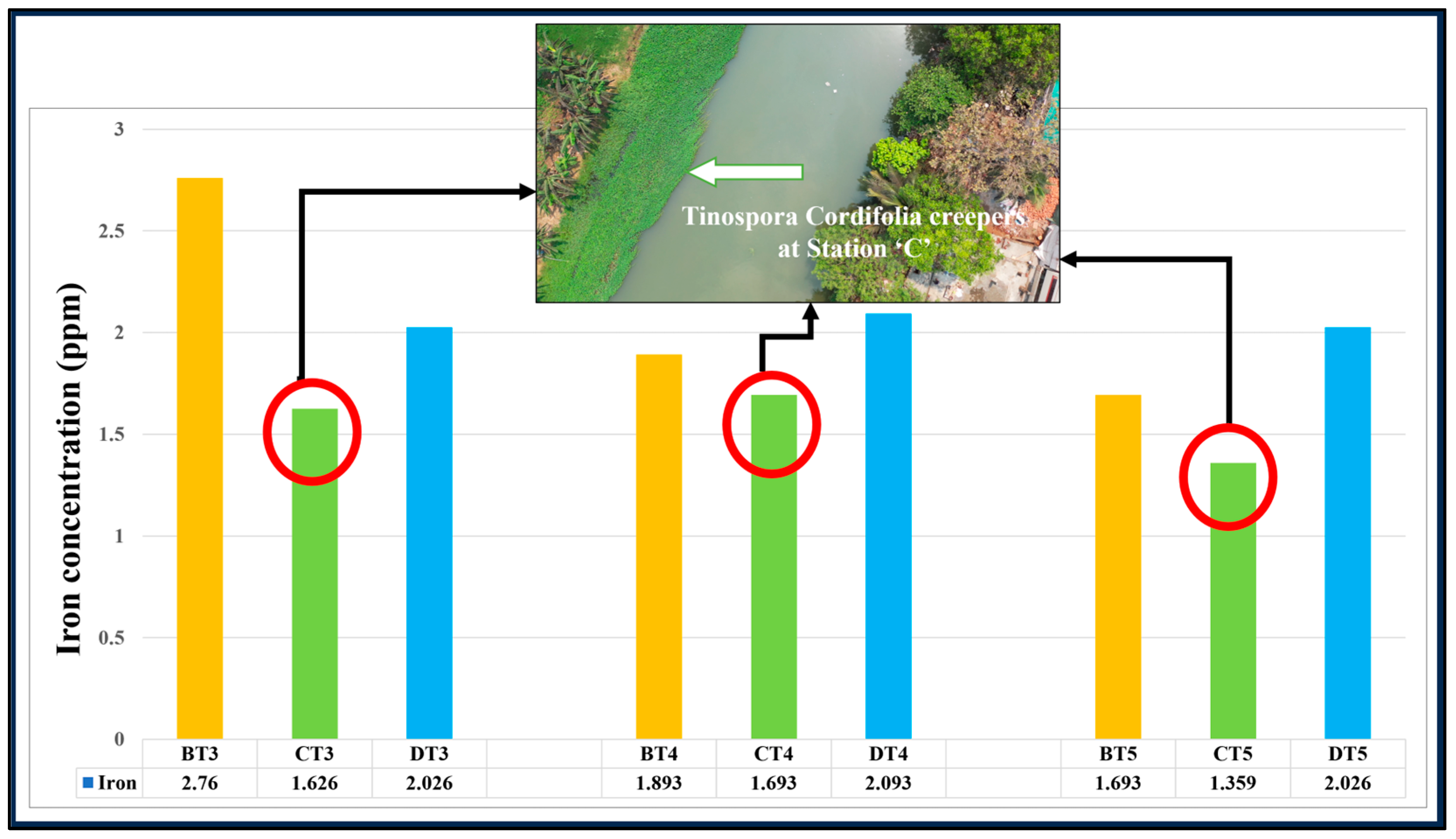

3.9. Effect of T. cordifolia Creepers Grown on GVC

3.10. Fate and Disposal of Iron-Loaded T. cordifolia Biomass

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, V.; Ahmed, G.; Vedika, S.; Kumar, P.; Chaturvedi, S.K.; Rai, S.N.; Vamanu, E.; Kumar, A. Toxic heavy metal ions contamination in water and their sustainable reduction by eco-friendly methods: Isotherms, thermodynamics and kinetics study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, J.; Husain, I.; Arif, M.; Gupta, N. Studies on heavy metal contamination in Godavari river basin. Appl. Water Sci. 2017, 7, 4539–4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, A.; Aziz, R.; Ghaffar, A.; Rafiq, M.T.; Feng, Y.; Saqib, Z.; Rafiq, M.K.; Awan, M.A. Occurrence, source identification and ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in water and sediments of Uchalli lake—Ramsar site, Pakistan. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 334, 122117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, T.V.; Nguyen, B.T. Heavy metal pollution in surface water bodies in provincial Khanh Hoa, Vietnam: Pollution and human health risk assessment, source quantification, and implications for sustainable management and development. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 343, 123216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Lin, F.F.; Wong, M.T.F.; Feng, X.L.; Wang, K. Identification of soil heavy metal sources from anthropogenic activities and pollution assessment of Fuyang County, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2009, 154, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Sharma, P.K. Status of Trace and Toxic Metals in Indian Rivers; River Data Directorate, Planning and Development Organisation, Central Water Commission: New Delhi, India, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IS: 10500-2012; Indian Standard-Drinking Water Specification (Second Revision). Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 2012.

- WHO. Iron in Drinking-Water; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- WHO. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality Third Edition Incorporating the First and Second Addenda, World Health Organization; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- Baby, J.; Raj, J.S.; Biby, E.T.; Sankarganesh, P.; Jeevitha, M.; Ajisha, S.; Rajan, S.S. Toxic effect of heavy metals on aquatic environment. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2010, 4, 939–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Shekhar, S. Iron contamination in the waters of Upper Yamuna basin. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagapathi, R.M.; Penmetsa, R.R.; Muppidi, S.R.; Golla, S.B.; Kondepudi, N. Micro-Biological Contamination of Drinking Water in Western Delta of West Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh, India. Int. Res. J. Environ. Sci. 2016, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Abd Elnabi, M.K.; Elkaliny, N.E.; Elyazied, M.M.; Azab, S.H.; Elkhalifa, S.A.; Elmasry, S.; Mouhamed, M.S.; Shalamesh, E.M.; Alhorieny, N.A.; Abd Elaty, A.E.; et al. Toxicity of Heavy Metals and Recent Advances in Their Removal: A Review. Toxics 2023, 11, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Pollution Control Board. The Environment (Protection) Rules. In General Standards for Discharge of Environmental Pollutants PART-A: Effluents; Central Pollution Control Board: New Delhi, India, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, K.; Nirmala, P.V. Heavy Metal Analysis in Agricultural Soils in Godavari River Basin of Rajahmundry Region, East Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh, India. Curr. Agric. Res. J. 2023, 11, 587–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, G.; Bhatt, S.; Paul, P. Tinospora cordifolia derived biomass functionalized ZnO particles for effective removal of lead(ii), iron(iii), phosphate and arsenic(iii) from water. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 34102–34113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, D.R.; Poudel, M.B.; Radoor, S.; Chang, S.; Lee, J. Decoration of dandelion-like manganese-doped iron oxide microflowers on plasma-treated biochar for alleviation of heavy metal pollution in water. Chemosphere 2024, 357, 141757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halaimi, F.Z.; Kellali, Y.; Couderchet, M.; Semsari, S. Comparison of biosorption and phytoremediation of cadmium and methyl parathion, a case-study with live Lemna gibba and Lemna gibba powder. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2014, 105, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schück, M.; Greger, M. Plant traits related to the heavy metal removal capacities of wetland plants. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2020, 22, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra Sekhar, K.; Kamala, C.T.; Chary, N.S.; Anjaneyulu, Y. Removal of heavy metals using a plant biomass with reference to environmental control. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2003, 68, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sao, K.; Pandey, M.; Pandey, P.K.; Khan, F. Highly efficient biosorptive removal of lead from industrial effluent. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2017, 24, 18410–18420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elaal, A.-E.M.; Aboelkassem, A.; Gad, A.A.M.; Ahmed, S.A.S. Removal of heavy metals from wastewater by natural growing plants on River Nile banks in Egypt. Water Pract. Technol. 2020, 15, 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, E.M.; Shaltout, K.H.; Almuqrin, A.H.; Aloraini, D.A.; Khedher, K.M.; Taher, M.A.; Alfarhan, A.H.; Picó, Y.; Barcelo, D. Uptake prediction of nine heavy metals by Eichhornia crassipes grown in irrigation canals: A biomonitoring approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 782, 146887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arivukkarasu, D.; Sathyanathan, R. Floating wetland treatment an ecological approach for the treatment of water and wastewater—A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 77, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muddada, S.; Kanamarlapudi, S.L.R.; Chintalpudi, V.K. Application of Biosorption for Removal of Heavy Metals from Wastewater. In Biosorption; Derco, J., Vrana, B., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Beni, A.A.; Esmaeili, A. Biosorption, an efficient method for removing heavy metals from industrial effluents: A Review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 17, 100503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Dwivedee, B.P.; Bisht, D.; Dash, A.K.; Kumar, D. The chemical constituents and diverse pharmacological importance of Tinospora cordifolia. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Gupta, A.; Singh, S.; Batra, A. Tinospora cordifolia (Willd.) Hook. F. Thomson-A Plant Immense economic potential. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2010, 2, 327–333. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, M.J.C.G.; Chattopadhyay, S. Antioxidant properties of a Tinospora cordifolia polysaccharide against iron-mediated lipid damage and γ-ray induced protein damage. Redox Rep. 2002, 7, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.K.; Kumar, K.; Kumar, A.; Mishra, H.S. Tinospora cordifolia (Willd.) Hook. f. and Thoms. (Guduchi) - validation of the Ayurvedic pharmacology through experimental and clinical studies. Int. J. Ayurveda Res. 2010, 1, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, N.; Siddiqui, M.B.; Khatoon, S. Pharmacognostic evaluation of Tinospora cordifolia (Willd.) Miers and identification of biomarkers. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2014, 13, 543–550. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Khatoon, S. Pharmacognostic Analysis of Tinospora cordifolia (Thunb.) Miers Respect Dioecy. Single-Cell Biology. 2019, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anu, C.; Rina, D.; Kiran, M.; Dinesh Kumar, M. Indian herb Tinospora cordifolia and Tinospora species: Phytochemical and therapeutic application. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.S.; Pandey, S.C.; Srivastava, S.; Gupta, V.S.; Patro, B.; Ghosh, A.C. Chemistry and medicinal properties of Tinospora cordifolia (Guduchi). Indian J. Pharmacol. 2003, 35, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, P.; Pandey, M.; Sharma, R. Defluoridation of Water by a Biomass: Tinospora cordifolia. J. Environ. Prot. 2012, 03, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, E.W.; Baird, R.B.; Eaton, A.D.; Clesceri, L.S. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association, American Water Works, Water Environment Federation: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.; Harisha, C.; Ruknuddin, G.; Prajapati, P. Quantitative estimation of Satva extracted from different stem sizes of Guduchi (Tinospora cordifolia (Willd.) Miers). J. Pharm. Sci. Innov. 2012, 1, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, N.; Thakur, N. Removal of organic dyes and free radical assay by encapsulating polyvinylpyrrolidone and Tinospora cordifolia in dual (Co–Cu) doped TiO2 nanoparticles. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 335, 122229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, M.S.; Prajapati, S.K. Resolving the dilemma of iron bioavailability to microalgae for commercial sustenance. Algal Res. 2021, 59, 102458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, H.; Goto, K.; Yotsuyanagi, T.; Nagayama, M. Spectrophotometric determination of iron(II) with 1,10-phenanthroline in the presence of large amounts of iron(III). Talanta 1974, 21, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. Spectroscopic determination of iron by 1,10-phenanthroline method. Talanta 2020, 21, 314–318. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, R.; Sharma, S.; Gurung, D.B.; Sitaula, B.K. Heavy metal contamination in sediments from vehicle washing: A case study of Olarong Chhu Stream and Paa Chhu River, Bhutan. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2019, 76, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasozi, N.; Tandlich, R.; Fick, M.; Kaiser, H.; Wilhelmi, B. Iron supplementation and management in aquaponic systems: A review. Aquac. Rep. 2019, 15, 100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briciu, A.-E.; Graur, A.; Oprea, D.I.; Filote, C. A Methodology for the Fast Comparison of Streamwater Diurnal Cycles at Two Monitoring Points. Water 2019, 11, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A.; Maharaj, S.; Prabhu, G.N.; Bhowmik, D.; Marino, A.; Akbari, V.; Rupavatharam, S.; Sujeetha, J.A.R.P.; Anantrao, G.G.; Poduvattil, V.K.; et al. Monitoring the Spread of Water Hyacinth (Pontederia crassipes): Challenges and Future Developments. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 631338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahima; Rahal, A.; Prakash, A.; Verma, A.K.; Kumar, V.; Roy, D. Proximate and elemental analyses of Tinospora cordifolia stem. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2014, 17, 744–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aman, A.M.N.; Selvarajoo, A.; Lau, T.L.; Chen, W.-H. Biochar as Cement Replacement to Enhance Concrete Composite Properties: A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 7662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Station Code | Latitude | Longitude | Identified Potential Sources of Pollution (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Aquaculture | Industries | Domestic Sewage | Poultry | |||

| A | 16.8531472° N | 81.6795417° E | 100 | - | - | - | - |

| B | 16.8348222° N | 81.6930083° E | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| C | 16.7632139° N | 81.6760444° E | 33.33 | - | 33.33 | 33.33 | - |

| D | 16.7313222° N | 81.6757361° E | 33.33 | - | 33.33 | 33.33 | - |

| E | 16.6853500° N | 81.6656528° E | 25 | 25 | - | 25 | 25 |

| F | 16.6287917° N | 81.6306889° E | 50 | 50 | - | - | - |

| G | 16.5651222° N | 81.5649194° E | 33.33 | 33.33 | 33.33 | - | - |

| H | 16.5370778° N | 81.5409972° E | 33.33 | 33.33 | - | 33.33 | - |

| I | 16.4750806° N | 81.5152972° E | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | - |

| J | 16.4360111° N | 81.5157583° E | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| S.no | GSB Sample Codes | DSB Sample Codes | PB Sample Codes | Iron Standard (ppm) | Volume (mL) | TC Biomass |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | GSB-1 | DSB-1 | PB-1 | 4 | 10 | Yes |

| 2. | GSB-2 | DSB-2 | PB-2 | 4 | 10 | Yes |

| 3. | GSB-3 | DSB-3 | PB-3 | 4 | 10 | Yes |

| 4. | GSB Blank | DSB Blank | PB Blank | 4 | 10 | No |

| 5. | GSBC-1 | DSBC-1 | PBC-1 | - | 10 | Yes |

| 6. | GSBC-2 | DSBC-2 | PBC-2 | - | 10 | Yes |

| 7. | GSBC-3 | DSBC-3 | PBC-3 | - | 10 | Yes |

| Station Code | Mean Concentration of Various Parameters at Each Station | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | TDS | ALK | Chlorides | TH | COD | Sodium | DO | |

| A | 7.74 | 174.93 | 64.81 | 24.99 | 131.07 | 54.35 | 14.45 | 4.71 |

| B | 7.81 | 186.61 | 74.83 | 29.71 | 129.87 | 65.27 | 15.20 | 4.50 |

| C | 7.79 | 219.92 | 78.03 | 44.80 | 156.04 | 85.35 | 23.69 | 5.31 |

| D | 7.77 | 231.64 | 72.94 | 48.00 | 141.63 | 107.53 | 23.94 | 3.98 |

| E | 7.78 | 244.95 | 82.99 | 51.51 | 158.57 | 85.93 | 26.64 | 3.87 |

| F | 7.64 | 254.95 | 94.71 | 49.90 | 145.88 | 86.27 | 30.17 | 3.27 |

| G | 7.71 | 249.79 | 93.22 | 50.70 | 143.13 | 107.53 | 28.14 | 4.29 |

| H | 7.59 | 244.88 | 93.02 | 49.03 | 142.44 | 86.27 | 34.62 | 3.90 |

| I | 7.60 | 241.57 | 103.23 | 48.08 | 156.27 | 95.80 | 35.91 | 3.07 |

| J | 7.62 | 243.29 | 113.08 | 49.03 | 150.87 | 108.27 | 44.18 | 3.66 |

| Station Code | Iron Concentration in ppm | Variance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | Min | Mean | Standard Deviation | ||

| A | 2.29 | 1.49 | 1.88 | 0.31 | 0.10 |

| B | 2.76 | 1.69 | 2.02 | 0.35 | 0.12 |

| C | 2.63 | 1.36 | 1.80 | 0.40 | 0.16 |

| D | 2.09 | 1.63 | 1.90 | 0.18 | 0.03 |

| E | 2.23 | 1.83 | 2.08 | 0.14 | 0.02 |

| F | 2.36 | 1.29 | 1.81 | 0.36 | 0.13 |

| G | 8.17 | 2.29 | 3.77 | 1.89 | 3.59 |

| H | 3.56 | 2.03 | 2.37 | 0.53 | 0.29 |

| I | 3.56 | 2.23 | 2.77 | 0.46 | 0.21 |

| J | 4.50 | 2.96 | 3.78 | 0.55 | 0.30 |

| TC Biomass (with Agitation) | (%) Iron Removal Efficiency (Re) in Diurnal GVC Samples | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | Min | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

| GSB-3 | 67.56 | 12.88 | 35.32 | 12.9 |

| DSB-3 | 72.45 | 18.26 | 41.77 | 13.59 |

| PB-3 | 100 | 26.87 | 72.43 | 15.84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raju, P.; Eregno, F.E.; Calay, R.K.; Raju, P.R.; Shaik, T.B. Biosorption of Iron-Contaminated Surface Waters Using Tinospora cordifolia Biomass: Insights from the Gostani Velpuru Canal, India. Water 2025, 17, 3020. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17203020

Raju P, Eregno FE, Calay RK, Raju PR, Shaik TB. Biosorption of Iron-Contaminated Surface Waters Using Tinospora cordifolia Biomass: Insights from the Gostani Velpuru Canal, India. Water. 2025; 17(20):3020. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17203020

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaju, Penupothula, Fasil Ejigu Eregno, Rajnish Kaur Calay, P. Ramakrishnam Raju, and Thokhir Basha Shaik. 2025. "Biosorption of Iron-Contaminated Surface Waters Using Tinospora cordifolia Biomass: Insights from the Gostani Velpuru Canal, India" Water 17, no. 20: 3020. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17203020

APA StyleRaju, P., Eregno, F. E., Calay, R. K., Raju, P. R., & Shaik, T. B. (2025). Biosorption of Iron-Contaminated Surface Waters Using Tinospora cordifolia Biomass: Insights from the Gostani Velpuru Canal, India. Water, 17(20), 3020. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17203020