1. Introduction

In the context of global resource constraints, hydropower, as a renewable and pollution-free clean energy source, is crucial for enhancing resource utilization efficiency and socio-economic benefits. Francis turbines are highly favored due to their advantages such as large installed capacity, broad adaptability to head ranges, and high efficiency under off-design conditions. Investigating the internal flow characteristics and runner forces of Francis turbines under various operating conditions is of great significance for the stability and safety of the units.

Shi et al. [

1] investigated the flow characteristics in the draft tube under different heads through full-flow passage numerical simulations. Chen et al. [

2] studied the flow field structure, pressure pulsation characteristics, and vortex evolution patterns of a 1000 MW Francis turbine under various guide vane openings. Wei et al. [

3] conducted a series of CFD analyses on a Francis turbine under partial load, design conditions, and overload ranges to examine the influence of J-grooves in the draft tube on its internal flow. Ji et al. [

4] performed numerical simulations of a Francis turbine under different output conditions, analyzing the flow characteristics in the draft tube, the mechanisms behind changes in flow behavior, and the effect of guide vane openings on vortex ropes. Zhang et al. [

5] explored complex flow phenomena in the draft tube of a Francis turbine and elucidated the physical mechanisms of vortex flows under different operating conditions. Jia et al. [

6] discussed the pressure pulsation characteristics and unsteady flow behavior of a Francis turbine under partial load conditions.

Cheng et al. [

7] employed very large eddy simulation (VLES) to study the channel vortices in a Francis turbine. Streamline analysis revealed a direct correlation between the reflux zone and the blade attack angle near the hub, with significant variations in vortex structure and intensity. Doussot et al. [

8] utilized RANS and LES methods to investigate a simplified low-head turbine runner model, demonstrating that both approaches accurately predicted the position and three-dimensional topology of channel vortices. Guo et al. [

9] conducted numerical and experimental studies on the cavitating two-phase flow in a scaled Francis turbine model. Their results indicated synchronized pressure oscillations in the draft tube cone across different locations, with inter-blade vortex frequency dominating the excitation of pressure fluctuations. Yang et al. [

10] explored the relationship between the performance and internal flow field of a double-runner Francis turbine, investigating its pressure pulsation characteristics through steady and unsteady numerical analyses of the prototype turbine’s full-flow passage using the Realizable k-ε model and polyhedral mesh method. Ghorani et al. [

11] applied entropy production theory to analyze the entropy generation distribution in a pump operating as a turbine. They found that energy losses primarily occurred at the blade leading edge, trailing edge, and suction/pressure sides due to inlet shock, flow separation, reflux, and channel vortices. Wang et al. [

12] proposed a novel entropy diagnostic model incorporating phase change, enabling quantitative evaluation of cavitation’s impact on fluid machinery operation. Through numerical simulations, Yamamoto et al. [

13] uncovered the physical mechanism of channel vortex development in Francis turbine blades under deep part-load conditions. Jing and Ducoin [

14] numerically simulated propeller flows and observed that the suction side of the blades was susceptible to cross-flow instability. Wang et al. [

15] simulated the internal flow field of a Francis turbine, obtained stress distributions on the blades, and performed turbine optimization design. Zhang et al. [

16] investigated the mechanism behind rapid temporal variations in pressure pulsations within the vaneless space of a model pump-turbine during runaway conditions through three-dimensional (3D) numerical simulations. Their results indicated that high-frequency pressure pulsation components from the runner dominated throughout the process. As the operating point traversed the S-shaped region of the characteristic curve, these components exhibited significant frequency fluctuations and amplitude amplification. Concurrently, certain low-frequency pulsations also intensified and became prominent. Choi et al. [

17] combined CFD analysis with experimental measurements to elucidate unsteady pressure pulsation phenomena. Their findings revealed that pressure pulsations originated not only from the periodic opening and closing of chambers formed between the rotor and casing walls but also from variations in the driven rotor speed. The induced pressure pulsations caused torque fluctuations, whose waveform patterns corresponded consistently with those of the pressure pulsations. Lu et al. [

18] conducted a comparative analysis of turbine efficiency, power output, and pressure pulsations by integrating computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations with experimental results. Using the PTN method, they examined changes in pressure pulsation signals before and after optimization, focusing on pressure-velocity vectors, dominant frequencies, pulsation intensity, and phase variations. Pang et al. [

19] applied computational fluid dynamics theory to analyze cavitation phenomena, passage vortices, and flow characteristics in a turbine at a Chinese hydropower station. Their study demonstrated that adjusting the guide vane opening concurrently altered the influence range and flow behavior of blade vortices. Within the mid-range of guide vane openings, vortex-induced pressure pulsations dominated inside the rotor, with the pulsation pressure reaching its maximum amplitude at 60% opening. Under large opening conditions, pressure pulsations were primarily manifested at the rotor blade passing frequency and concentrated in the vaneless space. Lu et al. [

20] explored the evolution of unsteady flow vortex structures and the propagation mechanisms of pressure pulsations in a two-stage pump-turbine operating in turbine mode. They identified that the primary source of pressure pulsations in the two-stage diffuser was the rotor–stator interaction between the impellers and their corresponding diffuser tongues.

The mechanical characteristics of the runner are closely linked to the energy conversion process in hydraulic turbines. In the field of Francis turbine structural integrity and dynamic characteristics research, numerous scholars have conducted systematic explorations through numerical simulations and experimental methods. Liu et al. [

21] systematically analyzed the primary fatigue damage mechanisms in hydraulic turbines (including Francis turbines) and provided a detailed discussion on the fundamental mechanisms leading to high stress in turbine units, such as rotor–stator interaction, vortex phenomena, and pressure pulsations. Based on the Navier–Stokes equations and the RNG k-ε turbulence model, Ruan et al. [

22] computed both steady and unsteady turbulent flows within the full passage. Their analysis revealed that the maximum dynamic stress distributed at the junction of the blade trailing edge and the crown exceeds the allowable stress value of conventional Francis turbine runners, leading to damage and even crack formation in this area. Using one-way coupling simulations, Negru et al. [

23] first conducted fluid flow analysis to obtain the distribution of fluid pressure on the blades, and subsequently analyzed the hydraulic stresses generated in Francis turbine runner blades under steady fluid flow conditions. The mechanical characteristics of the turbine runner are closely related to the energy conversion process of the hydraulic turbine. Roth et al. [

24] embedded pressure sensors and strain gauges into the surface of runner blades during experiments, measuring dynamic stresses and hydrodynamic pressures during operation. Their results confirmed a strong correlation between these parameters and the operating conditions. Zhuang et al. [

25] numerically analyzed the dynamic characteristics of the hydro-turbine generator shafting system under variations in blade outlet flow angle, outlet diameter, and guide vane opening angle, concluding that hydraulic instability primarily governed the overall trends in shafting dynamic behavior. Zhu et al. [

26] classified turbine vibration zones based on experimental data, identifying stress concentration at the blade trailing edge-hub junction and blade crown connection under small guide vane openings or low-head high-load conditions. Chen et al. [

27] investigated dynamic stresses in a 60 MW prototype Francis turbine runner, revealing significantly higher stresses under low-load conditions and recommending against using large units for peak-shaving and frequency regulation tasks. Xiao et al. [

28] conducted multi-condition CFD simulations of the full-flow passage in a Francis turbine and analyzed the dynamic stresses on the runner under specific operating points. Wang et al. [

29] numerically investigated the effects of non-uniform clearance distribution on pressure and radial forces at different locations, including the turbine crown chamber, vaneless space, and bottom ring chamber. Liu et al. [

30] studied the influence of axial installation deviations of the runner on the hydraulic axial force in a 1000 MW Francis turbine. They found that periodic vortex variations generated within the clearance due to geometric asymmetry and wall rotation effects. These vortices alter the velocity and pressure distributions, thereby determining the hydraulic axial force. Kan et al. [

31] employed a bidirectional fluid–structure interaction (FSI) approach to accurately characterize the vibration and dynamic stress responses of the turbine shaft system, with a focus on pressure fluctuations, runner vibrations, and blade stresses. The results indicated that pressure fluctuations within the flow passage are primarily driven by rotational flow effects and rotor–stator interactions. The structural design of the turbine flow passage significantly influences the radial forces exerted on the runner. Wang et al. [

32] conducted three-dimensional unsteady numerical simulations of a Francis turbine under different head conditions. Comparisons with model tests revealed that, under high-load conditions, periodic fluctuations in the vapor volume fraction within the draft tube induced low-frequency pressure pulsations (0.37 Hz) in external characteristic parameters such as turbine power and flow rate. Meanwhile, the radial force on the runner fluctuated at 1.85 Hz. Yuzo Yamaguchi et al. [

33] experimentally investigated fluctuations in the hydraulic radial force acting on the runner of a Francis turbine. Five turbine models with different specific speeds were tested. During power generation operations under partial load, the maximum amplitude occurred at the draft tube surge frequency. A frequency component corresponding to the runner rotational speed was consistently observed. Song et al. [

34] examined the fundamental characteristics of the swirling hydraulic torque on the runner back shroud in Francis turbines through model tests and calculations based on a volumetric flow model. In summary, significant progress has been made in the study of unsteady flow and structural dynamics in Francis turbines. The unsteady pressure pulsations in Francis turbines represent a complex phenomenon resulting from the combined effects of channel vortices, rotor–stator interaction, cavitation effects, and operating conditions. Their fundamental nature is intrinsically linked to the evolution of unsteady vortex structures within the flow passage. However, further investigation is still required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms governing the relationship between pressure pulsations and dynamic runner stresses across the entire operating range.

This study investigates a Francis turbine model through a systematic analysis of the internal flow patterns and pressure pulsation characteristics under various operating conditions, with a focus on the evolution of normal and tangential forces on the runner blades. A validated numerical framework employing the SST turbulence model, ZGB cavitation model, and VOF multiphase flow approach was developed to simulate complex turbine flow dynamics and pressure pulsations. Following experimental verification, comprehensive time-frequency analysis of pressure pulsation characteristics at monitoring points was performed. By correlating these findings with internal flow field patterns, this study reveals the mechanisms driving normal and tangential force variations on runner blades. The results establish a theoretical foundation for addressing operational stability concerns and advancing performance optimization in Francis turbines.

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents the mathematical model, including governing equations and cavitation model;

Section 3 describes the CFD setup covering geometry, grid generation with independence study, boundary conditions, and validation;

Section 4 analyzes internal flow patterns, pressure pulsations, and runner blade forces under various operating conditions; and

Section 5 summarizes the key conclusions on flow characteristics and blade loading.

2. Mathematical Model

The internal flow characteristics of fluid machinery are described by fluid dynamics equations. Based on the conservation of mass, momentum, and energy, the continuity equation, momentum equation, and energy equation can be derived. Since the temperature of the fluid remains essentially constant during flow, energy changes due to temperature variations are neglected. The continuity equation and momentum equation for incompressible fluids are as follows:

where

ρ represents density,

U represents velocity,

t represents time,

P represents pressure,

μ represents molecular dynamic viscosity,

μtur represents turbulent viscosity, and i, j, and k, respectively, represent the three components in the Cartesian coordinate system.

The Zwart–Gerber–Belamri cavitation model (ZGB) demonstrates strong adaptability and broad applicability for cavitating flows in water at ambient temperature. It is widely used in hydraulic machinery and has yielded results consistent with experimental data [

35,

36]. All numerical calculations in this study were conducted using the Zwart cavitation model.

In the formula, Fvap refers to Evaporation experience correction factor, αmuc refers to volume fraction of gas nuclei, Fcond refers to condensation experience correction factor.

The Volume of Fluid (VOF) multiphase flow model is an Eulerian-based interface-capturing approach that employs a volume fraction function to track the distribution of immiscible fluid phases within a fixed computational grid. This method is particularly effective for simulating interfacial flows involving two or more non-mixing fluids, where all phases share a common momentum equation while maintaining distinct volume fraction fields. The volume fraction of each phase is rigorously monitored throughout the domain, with the fundamental constraint that the sum of all phase fractions equals unity in every computational cell. This formulation ensures physical consistency while preventing numerical diffusion across phase boundaries, making the VOF model particularly suitable for simulating complex multiphase flow phenomena in hydraulic machinery.

The continuity equation for the phase volume fraction in the VOF model is as follows:

In the equation, mpq represents the mass transfer from phase q to phase p, and mpq denotes the mass transfer from phase p to phase q. Typically, the source term is 0.

3. Grids and CFD Setup

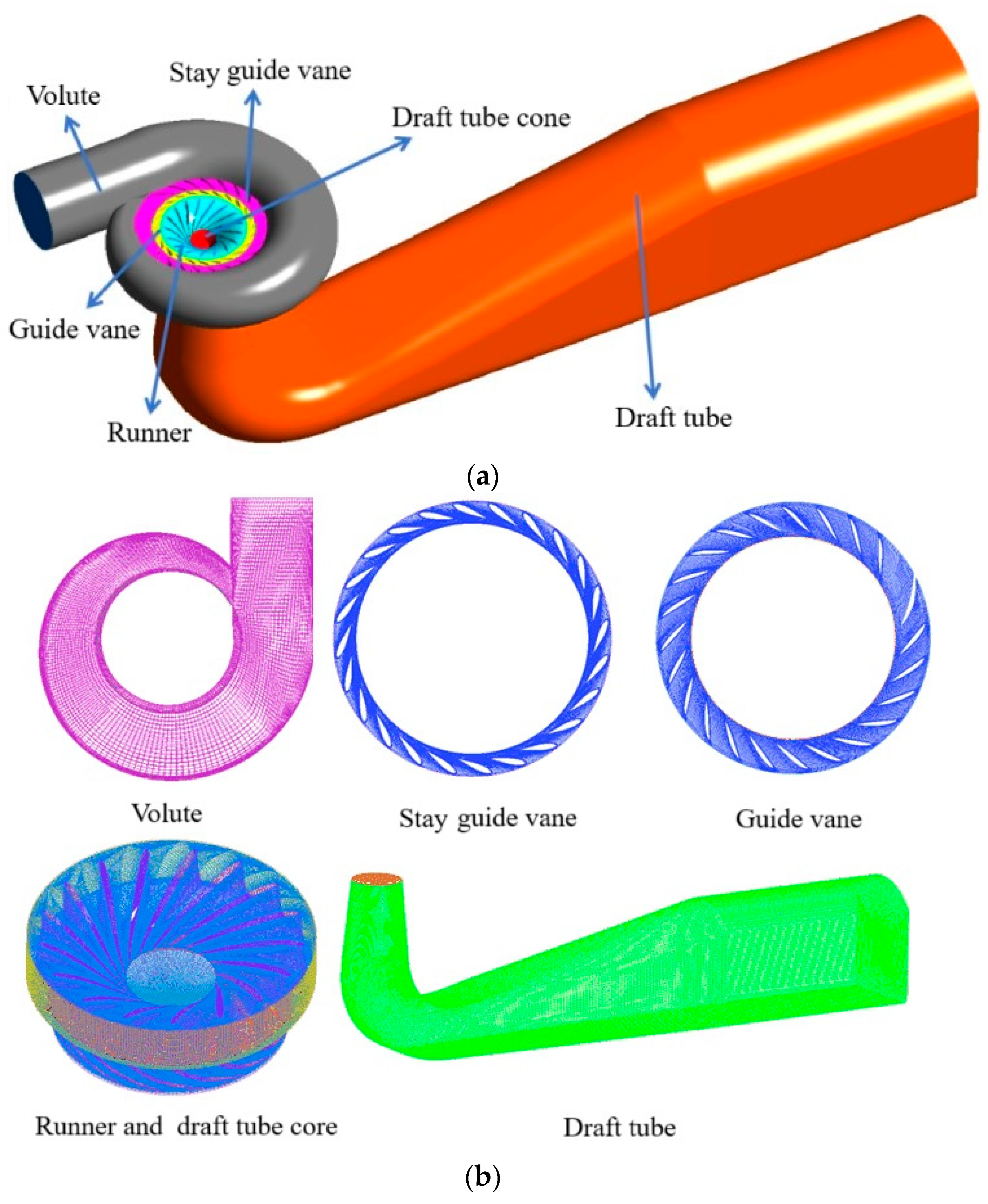

In this study, a three-dimensional full-flow channel of a Francis turbine was developed using UG·NX 12.0, which comprises the volute, guide vanes, stay guide vanes, runner, draft tube cone, and draft tube. To stabilize the outflow, the draft tube outlet was extended. The main parameters of the turbine are shown in

Table 1, and the three-dimensional model and grid are shown in

Figure 1.

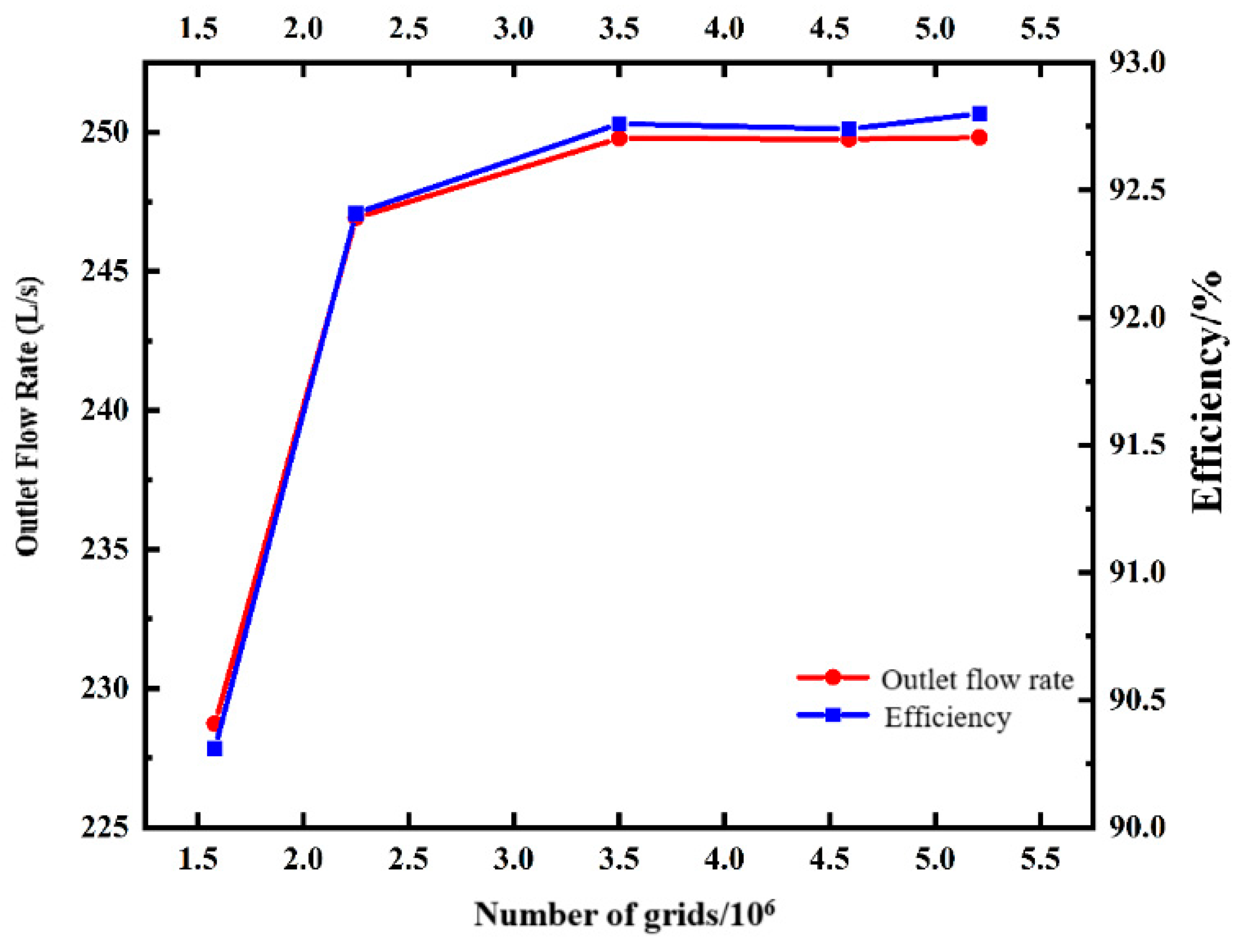

The full-flow passage model of the Francis turbine was discretized using structured meshes. A grid independence study was conducted through single-phase steady-state flow simulations, as illustrated in

Figure 2. The results demonstrate that both the outlet flow rate and efficiency stabilize when the mesh element count exceeds 2.9 million. Consequently, a total of 2.93 × 10

6 mesh nodes were ultimately selected for the computational model.

Numerical simulations of the Francis turbine under various operating conditions were conducted using CFX software. The total pressure at the volute inlet and the static pressure at the draft tube outlet section were set as boundary conditions for the flow field simulation. The SST turbulence model was employed to resolve turbulent flow structures, while the Zwart–Gerber–Belamri cavitation model coupled with the VOF multiphase flow approach was adopted to capture complex cavitation-induced flow characteristics.

In unsteady simulations, the boundary conditions remain consistent with those used in steady-state calculations. The convergence residual is set to 1 × 10−5, with data transfer across the rotor–stator interface handled using the Transient Rotor Stator method. A second-order backward Euler transient scheme is employed. For the initial several cycles, a time step of 0.006 s, corresponding to a 6-degree rotation of the runner, is applied. Once the calculation stabilizes, the time step is adjusted to 0.001 s, equivalent to a 1-degree rotation of the runner.

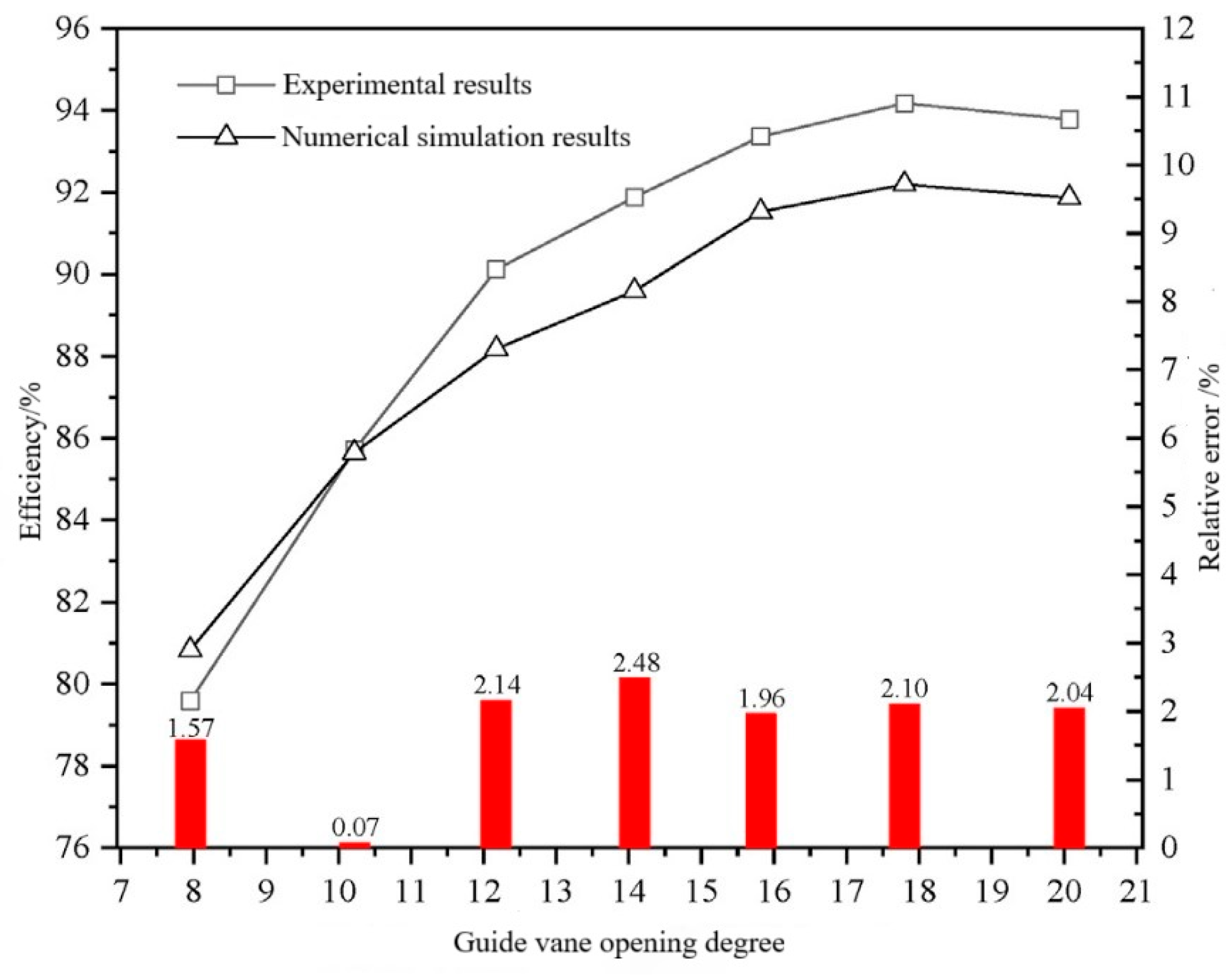

To validate the accuracy of the numerical simulation,

Figure 3 presents a comparison between experimental and simulated efficiency values across different guide vane openings. The two trend lines represent the variation patterns of experimental efficiency and numerical efficiency with changing guide vane openings, while the bar chart displays the corresponding relative errors at each operating condition. The analysis reveals that the efficiency values show a consistent upward trend as the guide vane opening increases, reaching their peak at the rated opening condition. Notably, the relative errors between experimental and simulation results remain within 3% for all operating conditions, demonstrating that the numerical model effectively captures and accurately predicts the actual flow phenomena.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Pressure Distribution Characteristics

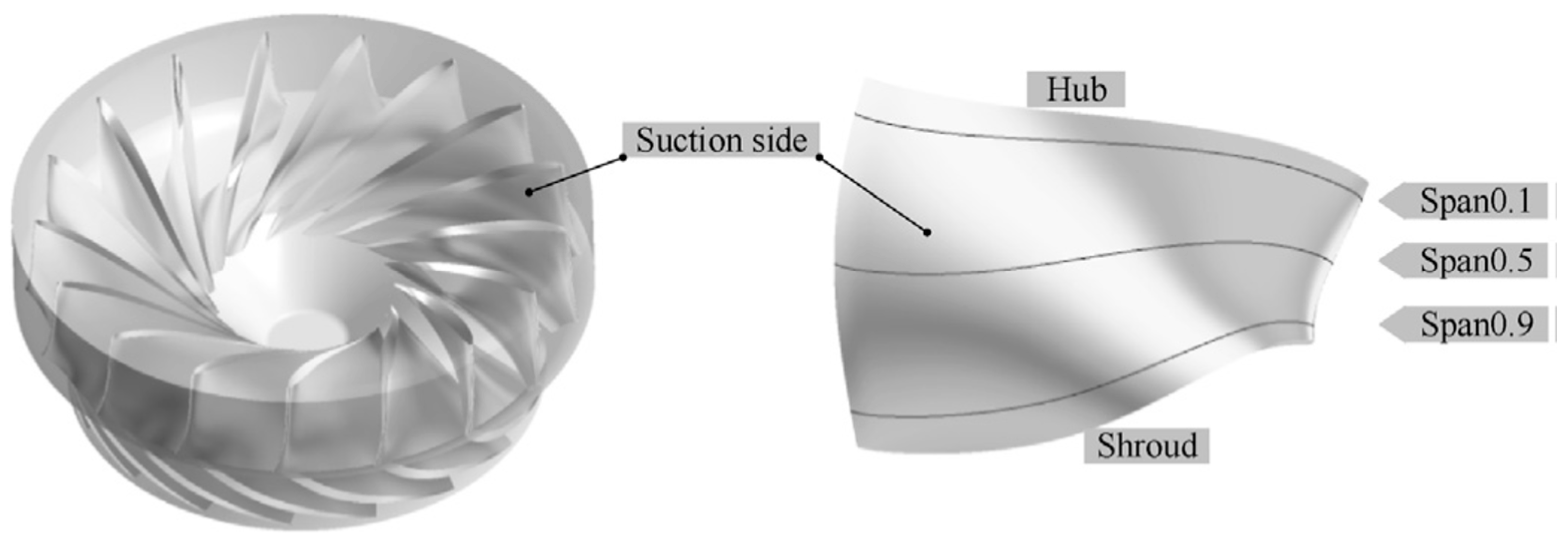

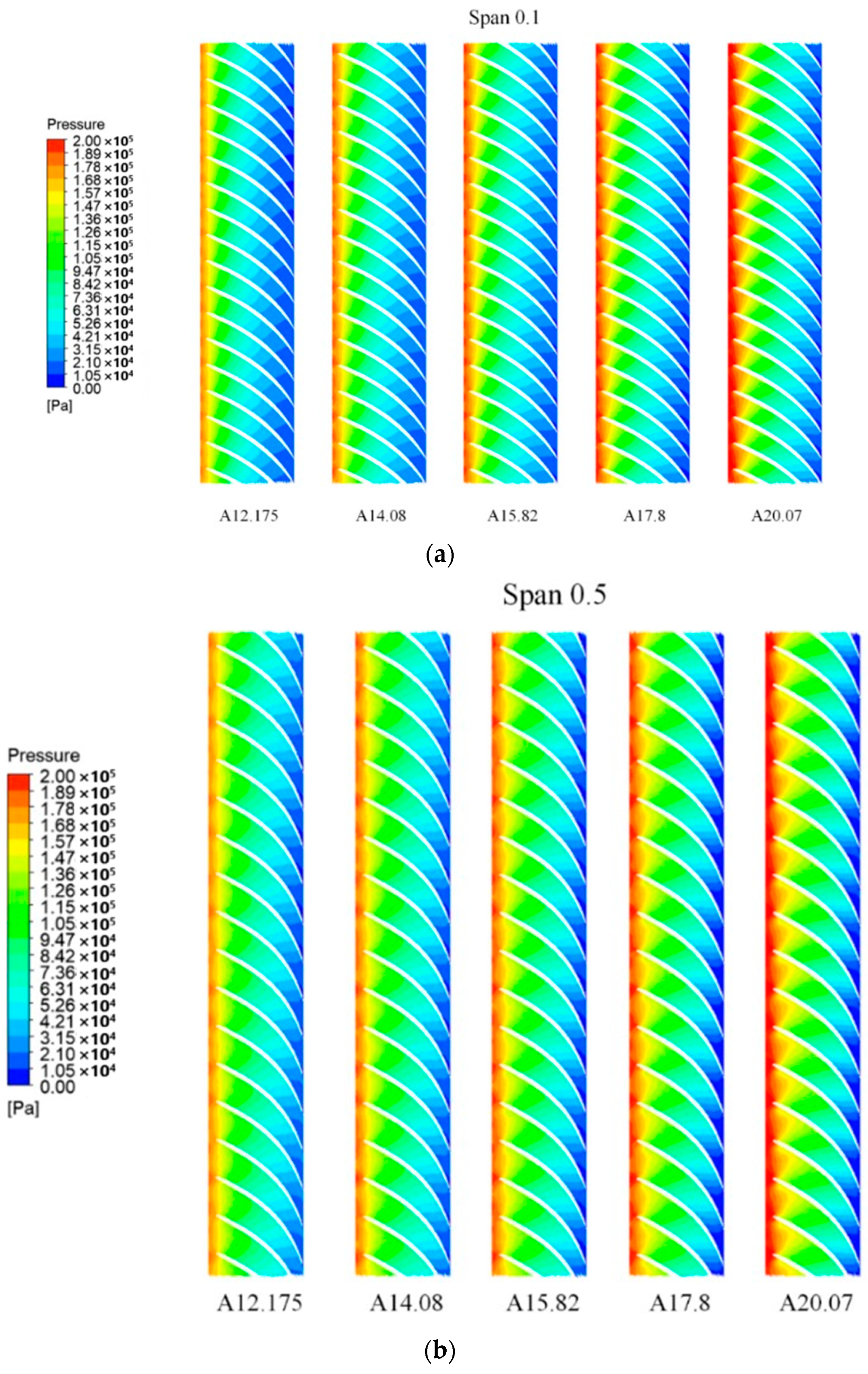

To analyze the internal flow characteristics within the runner flow passage under different operating conditions, cross-sections at varying span positions of the runner blade were selected, as illustrated in

Figure 4. The span values range from 0 to 1, where a higher span value indicates greater distance from the crown. When the span is 0 and 1, the corresponding sections represent the crown and band, respectively.

The pressure distribution across the runner flow passage under different operating conditions is shown in

Figure 5. On all three span sections, the fluid pressure exhibits a decreasing trend, dropping from an initial value of approximately 2 MPa at the runner inlet to a final value of about 0.1 MPa at the runner outlet. This pressure variation indicates that the pressure potential energy of the fluid is almost entirely converted into mechanical energy to drive the runner rotation as it passes through the flow passage.

As the guide vane opening increases, the pressure at the runner inlet is enhanced, while the pressure at the outlet remains close to 0.1 MPa. Comparing the pressure distributions at different spans, the upper flow passage of the runner is longer than the lower section, allowing more complete pressure release. Due to the similar pressure difference between the inlet and outlet, the shorter flow path in the lower region results in a significantly steeper pressure gradient, which may lead to flow separation and cavitation.

4.2. Analysis of Draft Tube Characteristics

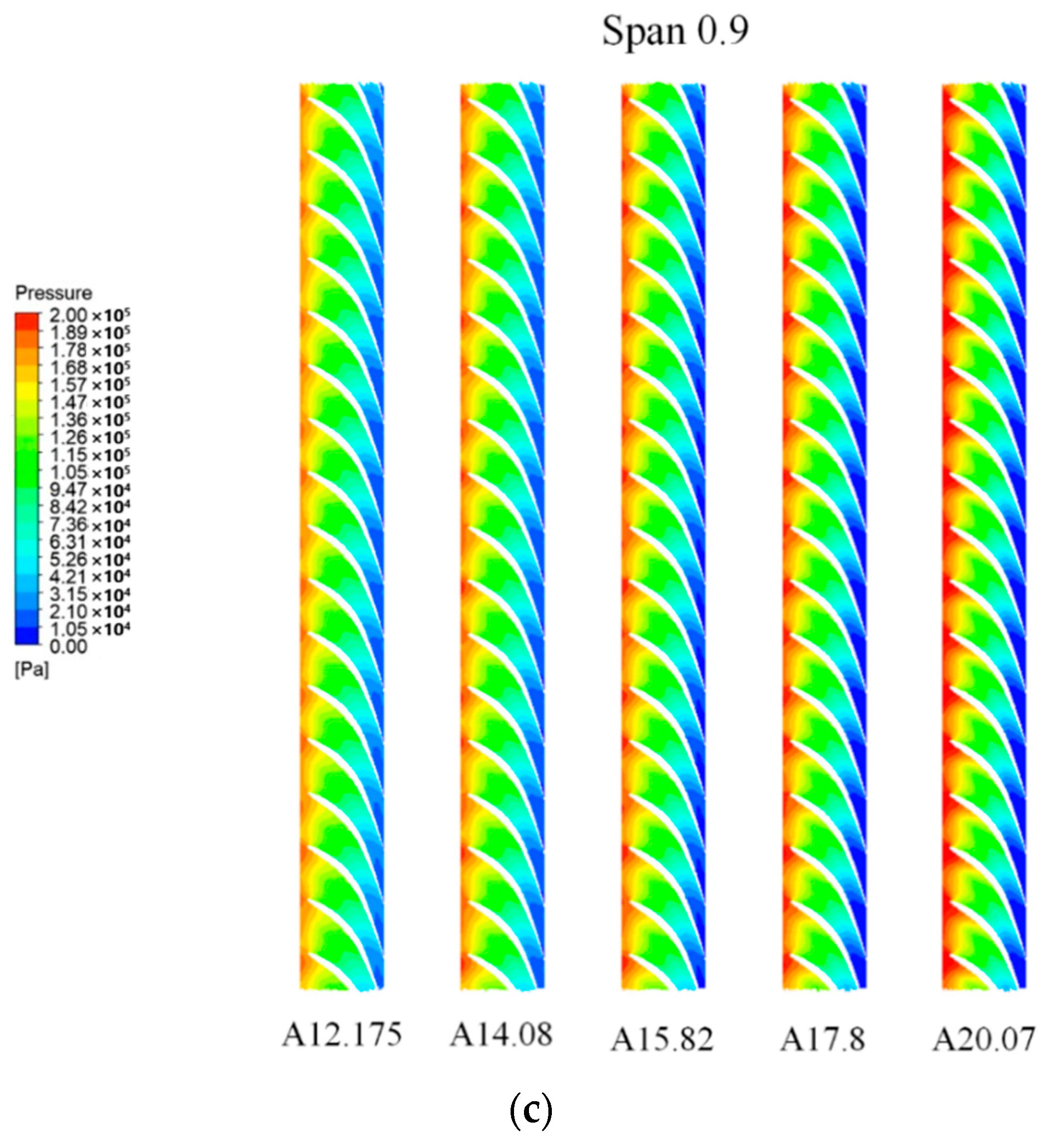

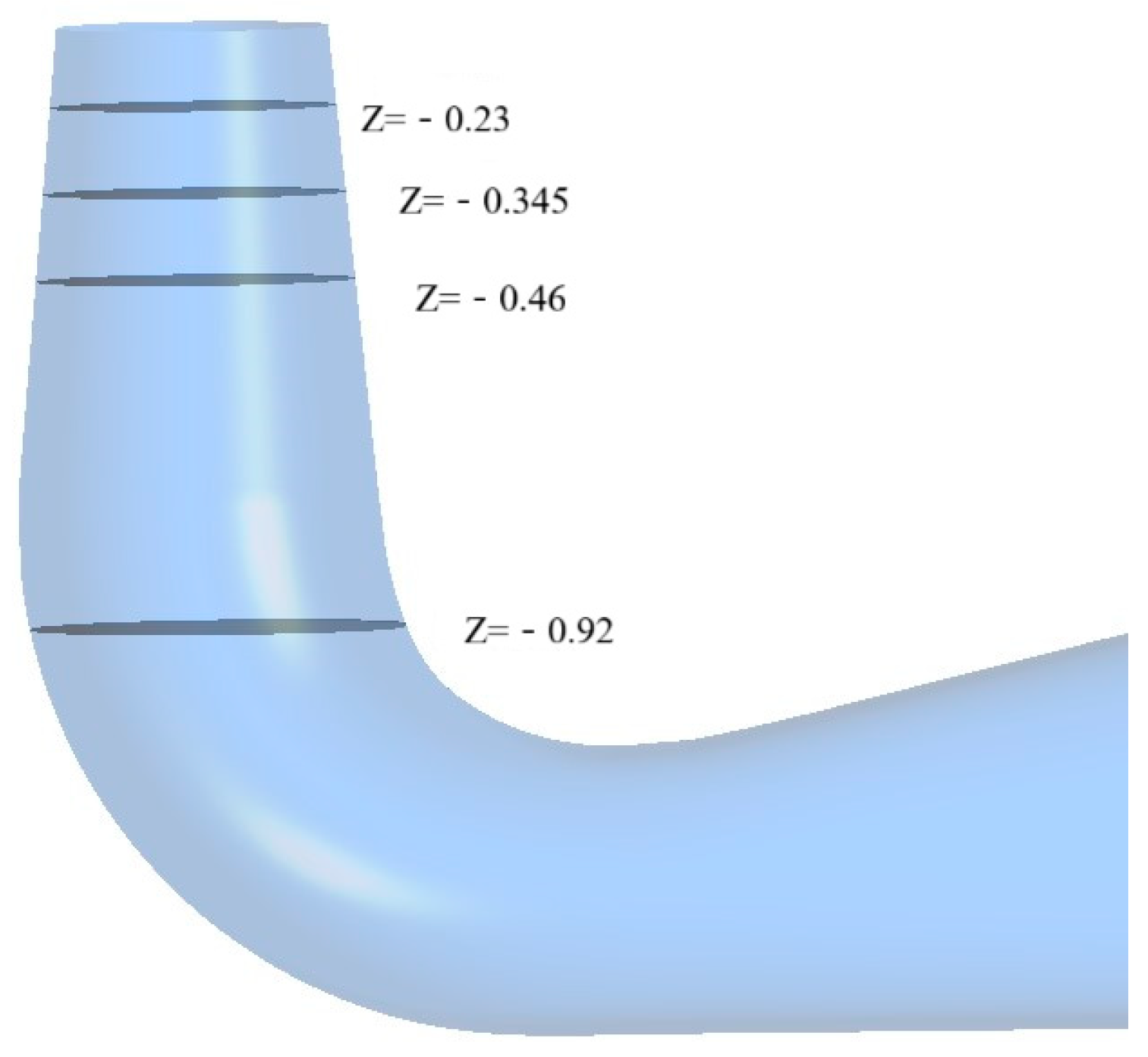

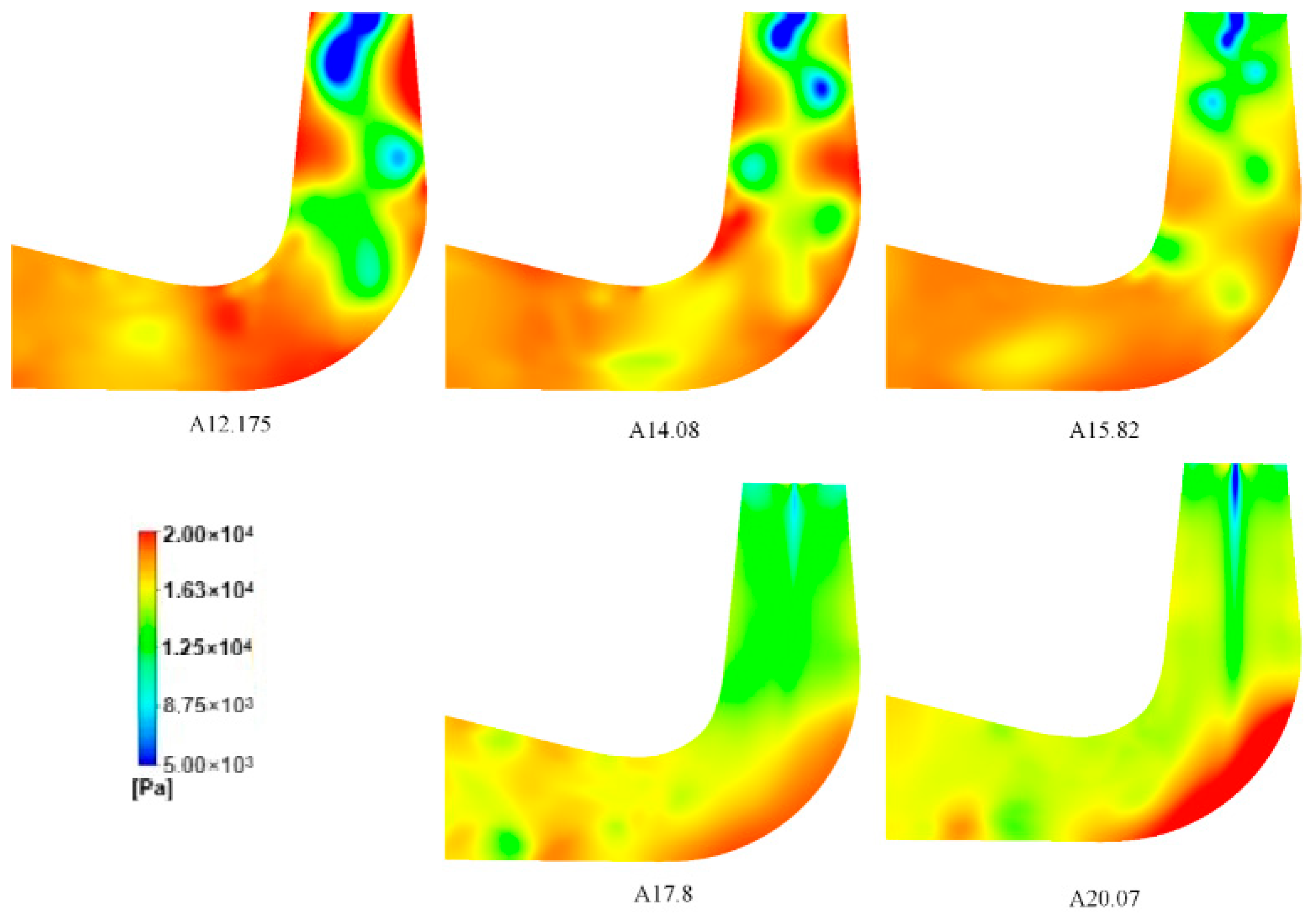

Cross-sections on the XY plane at different streamwise locations along the draft tube inlet are shown in

Figure 6, while the corresponding pressure distributions are presented in

Figure 7. Under low-flow conditions, a distinct eccentric low-pressure zone emerges on the draft tube cross-section, exhibiting an annular pressure gradient. As the guide vane opening increases to 15.82° and 17.8°, the eccentric low-pressure zone disappears. At an opening of 20.07°, a low-pressure zone reappears near the center. Under low-flow conditions, a high-pressure region forms along the periphery of the draft tube, creating a pressure difference with the eccentric low-pressure zone that induces radial flow and energy dissipation.

Under rated and high-flow conditions, the area of the low-pressure zone shrinks and becomes concentrated near the center, exerting minimal influence on the flow. Along the flow direction, the eccentric low-pressure zone gradually diminishes under low-flow conditions. In contrast, under rated and high-flow conditions, the pressure distribution becomes uniform starting from the Z = − 0.345 interface, with nearly homogeneous pressure distribution observed from the Z = − 0.46 interface onward.

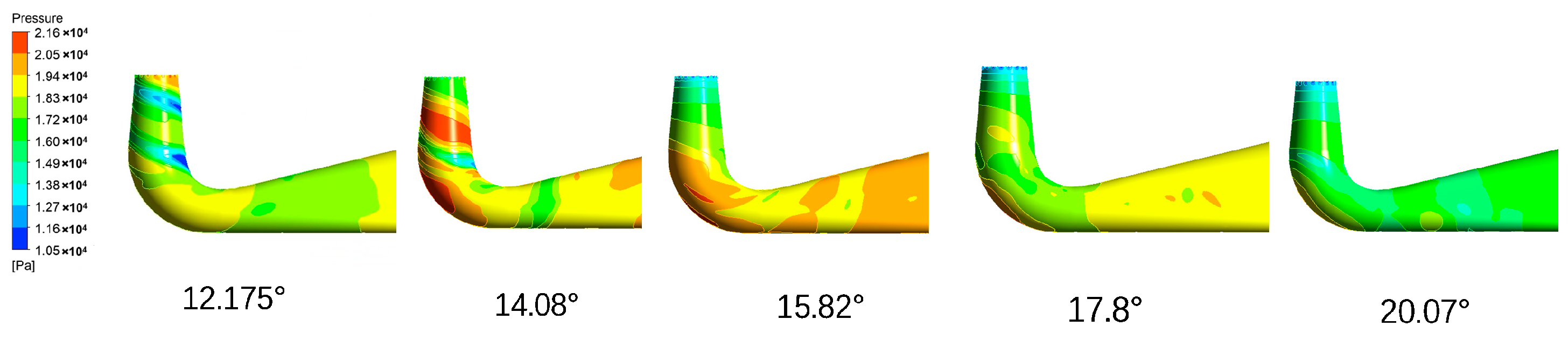

Figure 8 illustrates the pressure distribution on the YZ plane of the draft tube. Under low-flow conditions, the pressure on the YZ cross-section exhibits an S-shaped distribution, extending from the draft tube inlet to the elbow section. As the guide vane opening increases below the rated condition, the S-shaped characteristic gradually attenuates. Under high-flow conditions, a linear low-pressure zone emerges along the center of the conical section and extends into the elbow, while a high-pressure region forms near the outer bend due to fluid impact. In the diffuser section, alternating high and low-pressure zones occur along the lower wall, resulting from flow separation and vortex-induced disturbances.

Figure 9 illustrates the pressure distribution on the draft tube wall,

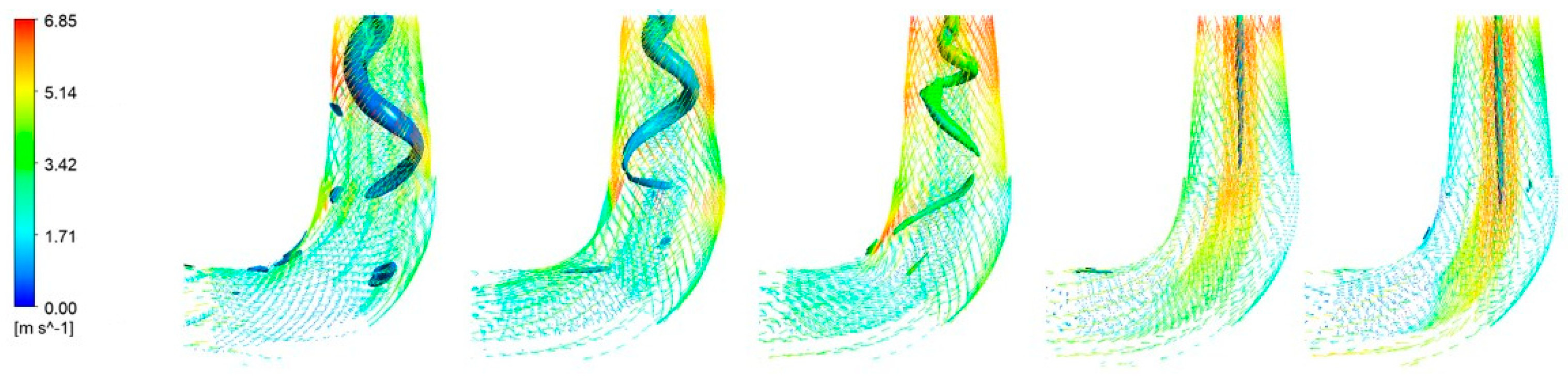

Figure 10 illustrates the morphology of the vortex rope and the distribution of internal velocity vectors in the draft tube under different guide vane openings. The vortex rope depicted in the figure is identified using the Omega vortex identification method, while the color of the velocity vectors represents the magnitude of the velocity at each location. This figure allows for a direct observation of the vortex rope’s structure within the draft tube and the accompanying velocity vector distribution. From

Figure 9, it is evident that the fluid enters the draft tube at a high velocity. As the fluid continues to move along the streamline direction, its velocity gradually decreases. Under low-flow conditions, the vortex rope in the draft tube exhibits a spiral shape. The presence of the vortex rope significantly alters the structure of the flow field and induces a blocking effect on the fluid flow. The region between the spiral vortex rope and the wall of the draft tube’s straight conical section experiences a narrowed flow passage and accelerated flow velocity, resulting in a localized high-velocity zone. This phenomenon has a significant impact on both energy conversion and the flow stability within the draft tube. Under high-flow conditions, the straight conical vortex rope is surrounded by high-velocity fluid particles, which extend to the vicinity of the elbow section. In contrast, under non-cavitation conditions, the vortex rope in the draft tube is longer and exerts a more pronounced influence on the entire flow field, with high-velocity fluid particles distributed over a wider area. The above analysis reveals the differences in the internal flow structures of the draft tube under various operating conditions and highlights the influence of the vortex rope on the fluid dynamics.

4.3. Analysis of Pressure Fluctuations

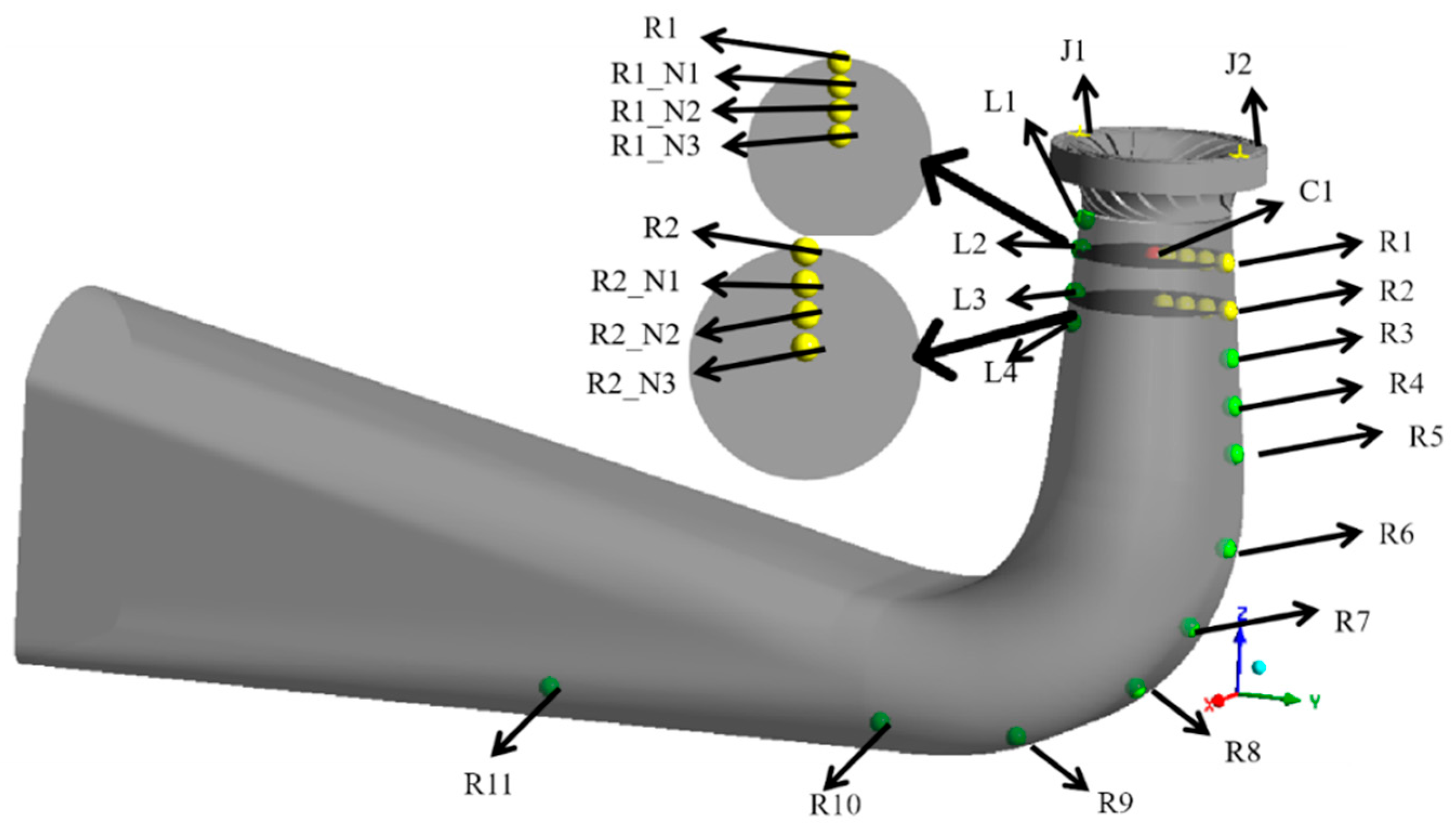

As shown in

Figure 11, pressure fluctuation characteristics during turbine operation were captured through a systematically arranged monitoring point network. Two monitoring points, J1 and J2, were respectively established at the interface between the guide vanes and the runner to investigate the strong wake pulsations from the fixed guide vanes and the rotor–stator interaction pulsations between the stationary guide vanes and the rotating runner. Eleven monitoring points, R1 to R11, were arranged at specific intervals along the inner wall of the draft tube to simultaneously capture pressure pulsations at different locations on the draft tube surface. Additionally, two planes at R1 and R2 were each equipped with a series of monitoring points uniformly distributed along the radius from the center to the draft tube wall. The denser arrangement of monitoring points near the draft tube inlet enables real-time and effective acquisition of flow information at this critical location.

The pressure data from monitoring points were normalized for dimensionless analysis.

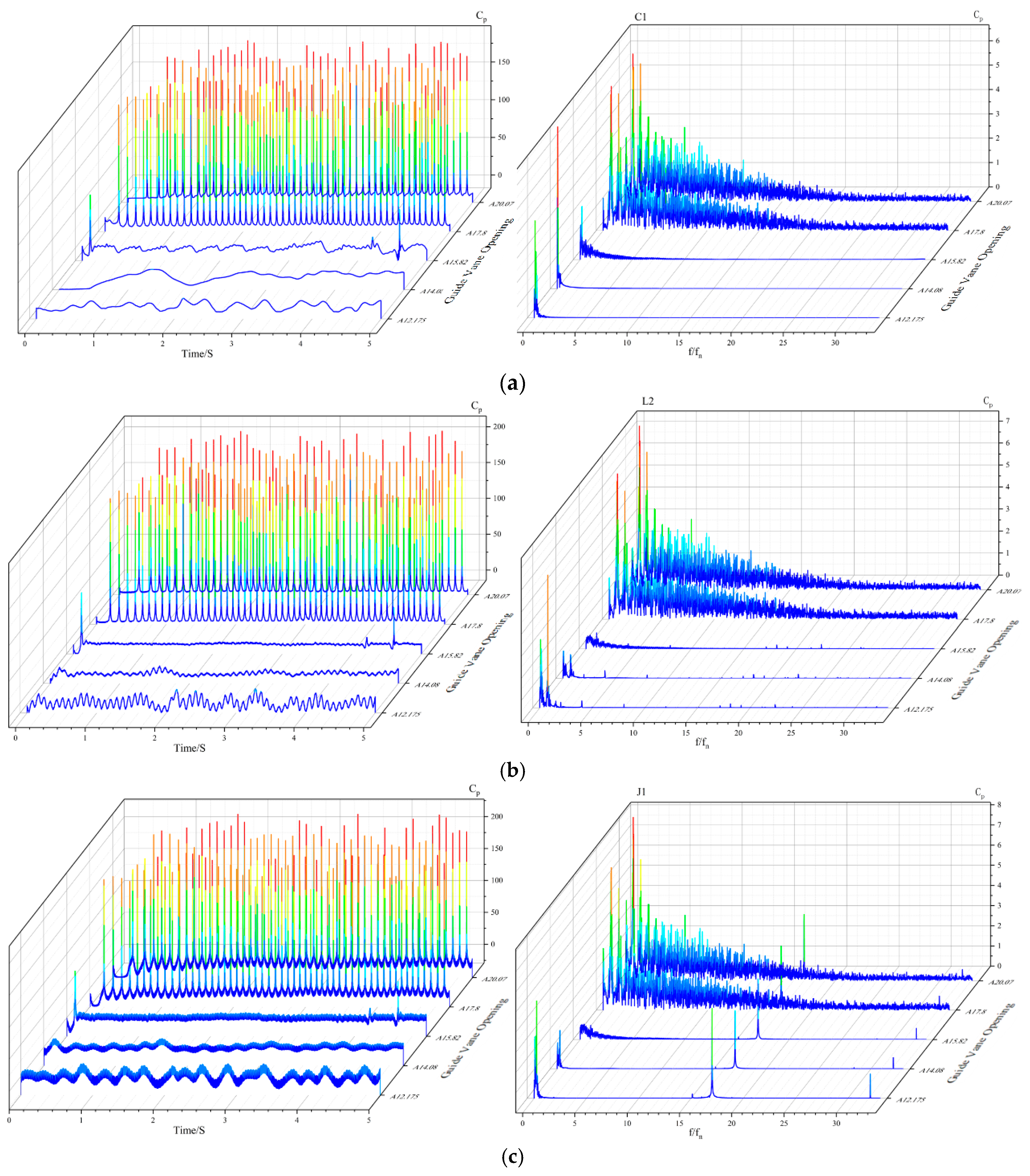

Figure 12 shows the time-domain and frequency-domain characteristics of pressure fluctuations at points C1, L2, and J1 under different operating conditions. Point C1, located at the center of the draft tube conical section, experiences significant circumferential velocity when water enters, inducing intense vortex motion that leads to cavitation and the formation of a draft tube vortex rope. In the time-domain plots, pressure variations remain stable under low-flow conditions but exhibit abrupt changes under high-flow conditions. Frequency-domain analysis reveals that pressure fluctuations under all guide vane openings exhibit low-frequency characteristics. The dominant frequency is 0.08 times the rotational frequency at an opening of 12.175°, 0.04 times at 14.08°, increases to 0.17 times at 15.82°, jumps to 0.78 times at 17.8°, and drops to 0.67 times at 20.07°. As the guide vane opening increases, the dominant frequency first rises and then decreases. Additionally, a secondary dominant frequency phenomenon is observed under high-flow conditions. The pressure fluctuation frequency at point C1 coincides with the variation frequency of the vortex rope length, primarily influenced by the periodic oscillations of the rotating vortex rope within the draft tube.

Point L2 is situated on the inner surface of the left side of the draft tube, and its pressure fluctuation characteristics reflect the force conditions on the inner wall. Under low-flow conditions, the pressure fluctuations at point L2 exhibit strong periodicity. The pressure fluctuations on the draft tube wall are primarily governed by the combined effects of the spiral vortex rope’s rotation and its periodic elongation-contraction dynamics. The dominance of rotational versus axial contraction effects shifts with changes in guide vane opening. Under high-flow conditions, the conical vortex rope stabilizes structurally, and wall-pressure fluctuations become predominantly driven by the periodic length variation in the vortex rope.

Point J1 is located at the interface between the movable guide vanes and the runner. Its pressure fluctuation characteristics reflect the influence of fixed guide vane wakes on high-frequency runner fluctuations and the rotor–stator interaction effect. Time-domain plots show that the pressure fluctuations at point J1 exhibit nested periodic characteristics: on a short time scale, clear periodic oscillations are observed, widening the time-domain curve; on a long-time scale, periodic oscillations determine the amplitude of the short-time-scale fluctuations. Frequency-domain analysis indicates diverse pressure fluctuation frequencies at point J1. At a 12.175° opening, amplitudes at 0.24 times and 17 times the rotational frequency are similar, while the amplitude at 32 times is relatively small. At 14.08°, the dominant frequency is 17 times the rotational frequency, with a secondary frequency at 0.26 times. At 15.82°, the dominant frequency remains at 17 times, though low-frequency regions also show notable amplitudes. At 17.8°, the dominant frequency is 0.78 times, with significant influence still observed at 17 times. At 20.07°, the dominant frequency is 0.67 times, and a peak emerges at 17 times the rotational frequency. Analysis reveals that all operating conditions exhibit certain amplitudes at 17 times and 32 times the rotational frequency. The 17-times component corresponds to the 17 blades of the runner, directly indicating the role of rotor–stator interaction in pressure fluctuations. The low peak at 32 times the rotational frequency reflects the minor influence of fixed guide vane wakes on pressure fluctuations.

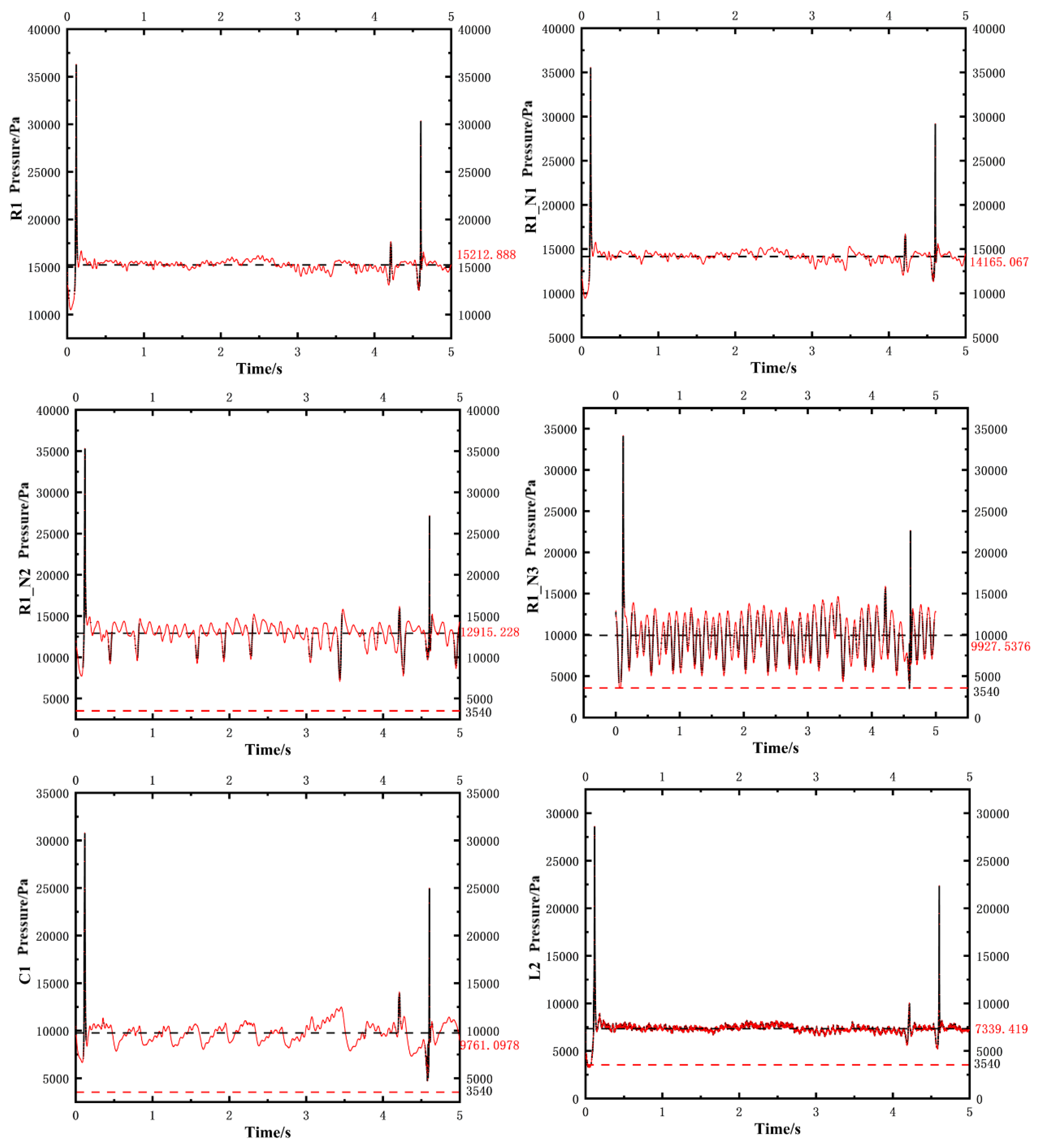

Six monitoring points, C1, L2, R1, R1_N1, R1_N2, and R1_N3, are positioned on the same horizontal cross-section of the straight conical section at the draft tube inlet. The pressure pulsations at these six points under the rated opening condition were monitored in this study. The pressure pulsation variation curves are shown in

Figure 13. In

Figure 13, the red dashed line indicates the 3540 Pa reference line, corresponding to the saturated vapor pressure of water at room temperature, while the black dashed line represents the mean value of the pressure pulsations at each point, with specific numerical values labeled on the right y-axis. It can be clearly observed from the figure that under the guide vane opening of 15.82°, no cavitation occurs at any of the six points. Under the rated opening condition, the flow state at the draft tube inlet remains relatively stable. The pressure values across these points follow the order: R1 > R1_N1 > R1_N2 > R1_N3 ≈ C1 > L2, indicating a gradual decrease in pressure from the outer wall toward the center of the draft tube, with an eccentric pressure distribution pattern. Pressure fluctuations become more pronounced near the center of the draft tube, while values tend to stabilize closer to the wall surface.

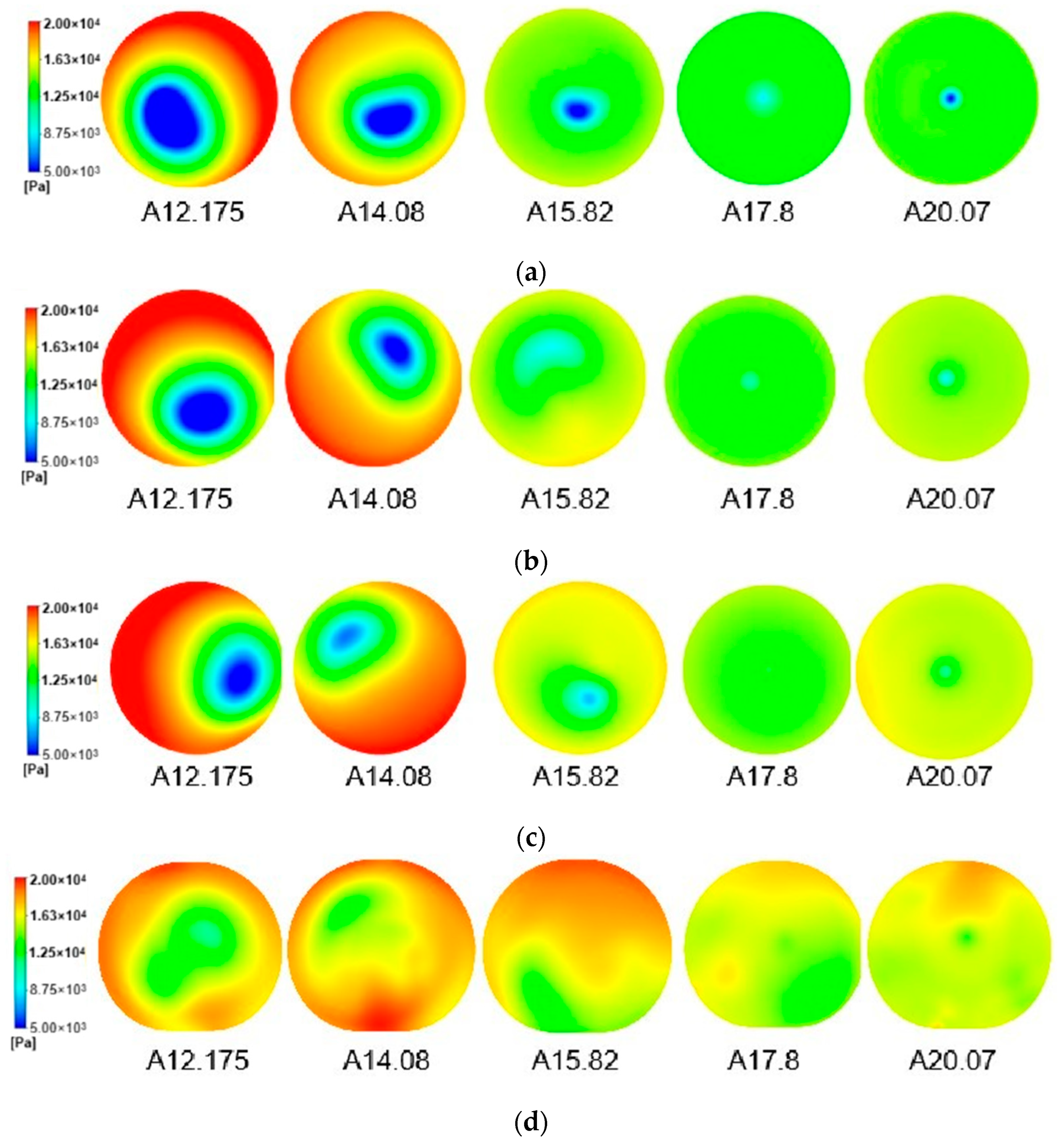

4.4. Analysis of Runner Blade Load Characteristics

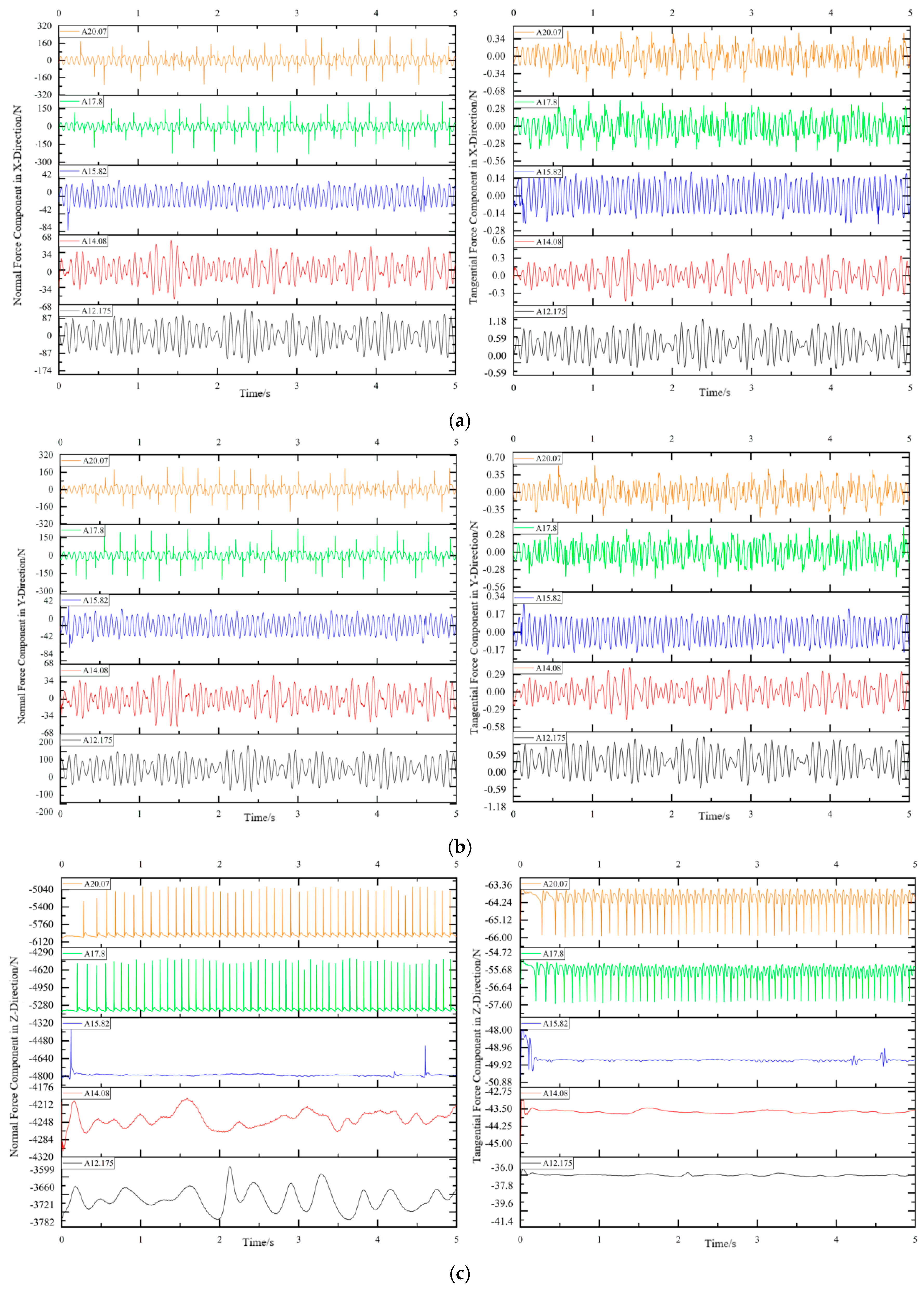

The forces acting on the runner blades were decomposed into normal and tangential components, which were further projected onto the X, Y, and Z directions to observe the mechanical characteristics during turbine operation. The variation trends of the normal and tangential force components along the X, Y, and Z axes are shown in

Figure 14. Among them, each force variation trend encompasses five guide vane opening conditions from the numerical simulations.

For three-dimensional curved blades, the normal force drives the rotation of the blades, while the tangential force hinders fluid flow and causes energy loss. The force variation curves in the X, Y, and Z directions indicate that the normal force is significantly greater than the tangential force. In Francis turbines, most of the fluid energy is converted to drive the runner for power generation, with only a small portion dissipated due to viscous friction. The normal and tangential forces exhibit opposite trends: when the normal force reaches a peak, the tangential force falls to a trough, and an increase in normal force corresponds to a decrease in tangential force.

A longitudinal comparative analysis across different guide vane openings reveals that flow stability is highest when the opening approaches the rated condition (A15.82), where the force characteristic curves exhibit the smoothest profiles. Under low-flow conditions (A12.175, A14.08), the force curves demonstrate relatively minor abrupt fluctuations. In contrast, at openings of 17.8° and 20.07°, severe force pulsations occur, which may compromise the operational safety of the turbine unit. At guide vane openings of 12.175° and 14.08°, the normal force in the X-direction remains relatively stable, generally not exceeding 90 N, while the peak variation in tangential force is approximately 0.5 N. Under high-flow conditions, such as at 17.8°, the normal force in the X-direction reaches about 175 N, and at 20.07°, it reaches approximately 190 N. The force characteristic curves in the XY directions exhibit distinct periodicity. Under low-flow conditions, the periodic variation frequency is approximately 12 Hz, corresponding to about 0.8 times the rotational frequency. At the rated guide vane opening, the periodic frequency is around 15 Hz, nearly equal to the rotational frequency. Under high-flow conditions, the force curves demonstrate nested periodic cycles: in addition to the 15 Hz component, a low-frequency variation at 0.3–0.4 times the rotational frequency is observed.

Additionally, due to flow instability during operation, periodic fluctuating forces are observed, with both normal and tangential forces oscillating around zero. However, a comparative analysis of the two graphs reveals that the magnitude of normal force fluctuations is significantly greater than that of tangential force fluctuations. Compared to the viscous effects of the fluid, the fluctuating impact forces perpendicular to the blade surface are substantially larger. This observation provides valuable insights for the design and material selection of runner blades.

In the Z-direction force diagram, under high-flow conditions, abrupt force fluctuations at 0.6–0.8 times the rotational frequency are observed on the runner blades. At guide vane openings of 17.8° and 20.07°, the normal force increases instantaneously and then decreases abruptly to near its original value, while the tangential force decreases instantaneously and subsequently increases back to approximately its initial level. In contrast, for guide vane openings of 12.175°, 14.08°, and 15.82°, the force variation curves exhibit no clear periodicity. Therefore, statistical analysis was performed on the force magnitudes at each time point, and

Table 2 presents the mean values and standard deviations of the curves. The mean values reflect the magnitudes of the normal and tangential forces, while the standard deviations indicate the intensity of the variations. Under low-flow conditions, the flow remains relatively stable, resulting in minor fluctuations in the runner blade forces. Conversely, high-flow conditions lead to significant variations in blade forces. Under high-flow conditions, increased flow rates generate strong wake vortices downstream of the fixed guide vanes, intensify rotor–stator interactions, cause flow separation on the runner blade surfaces, and induce extensive channel vortices within the flow passage, collectively enhancing abrupt force fluctuations on the runner blades.

Under ideal operating conditions, runner blades should experience continuous and stable forces during operation. However, in actual operation, the blades are subjected to continuously acting periodic loads. Long-term exposure to such hydraulic excitation forces can lead to fatigue damage of the blades, causing unit vibration, noise, and even incidents such as thrust bearing overload failure and unit lifting. Based on the frequency characteristics of the runner force characteristic curves, wake from fixed guide vanes, rotor–stator interaction, and draft tube vortex ropes contribute to force fluctuations on the runner blades. The mechanical characteristic curves show that forces in the X and Y directions pulsate around zero, while the force in the Z direction fluctuates around a constant value, with normal force pulsations being significantly greater than tangential force pulsations. The force frequencies in the X and Y directions are close to the rotational frequency of the runner.