Abstract

Electrocoagulation (EC) employing aluminum–aluminum (Al–Al) electrodes was investigated for hospital wastewater treatment, targeting the removal of turbidity, soluble chemical oxygen demand (sCOD), and total dissolved solids (TDS). A hybrid modeling framework integrating response surface methodology (RSM) and artificial neural networks (ANN) was developed to enhance predictive reliability and identify energy-efficient operating conditions. A Box–Behnken design with 15 experimental runs evaluated the effects of pH, current density, and electrolysis time. Multi-response optimization determined the overall optimal conditions at pH 7.0, current density 20 mA/cm2, and electrolysis time 75 min, achieving 94.5% turbidity, 69.8% sCOD, and 19.1% TDS removal with a low energy consumption of 0.34 kWh/m3. The hybrid RSM–ANN model exhibited high predictive accuracy (R2 > 97%), outperforming standalone RSM models, with ANN more effectively capturing nonlinear relationships, particularly for TDS. The results confirm that EC with Al–Al electrodes represent a technically promising and energy-efficient approach for decentralized hospital wastewater treatment, and that the hybrid modeling framework provides a reliable optimization and prediction tool to support process scale-up and sustainable water reuse.

1. Introduction

Hospital wastewater contains a complex mixture of pharmaceuticals, antibiotics, disinfectants, and pathogenic microorganisms, many of which are resistant to biodegradation and exhibit antimicrobial properties. In addition to pharmaceutical residues, hospital effluents are characterized by high temporal variability, the presence of disinfectants and cytotoxic compounds, and strict regulatory discharge limits, making them particularly difficult to manage using conventional biological processes [1,2]. Although biological processes such as activated sludge and membrane bioreactors are commonly applied, their effectiveness is often compromised by microbial inhibition and the low biodegradability of hospital effluents [3]. These limitations highlight the need for alternative treatment technologies that are less reliant on microbial activity and better suited to toxic and variable waste streams.

Electrocoagulation (EC) has emerged as a promising physicochemical process for wastewater treatment due to its operational simplicity, low chemical input, and effective removal of turbidity, suspended solids, and organic pollutants [4,5,6]. The process relies on the in-situ generation of coagulant species via electrochemical dissolution of metal electrodes under direct current. Among the most widely used materials, aluminum and iron electrodes exhibit distinct electrochemical behaviors and form different hydroxide species that govern pollutant removal mechanisms. Aluminum electrodes typically generate Al3+ ions that hydrolyze to form amorphous Al(OH)3 flocs with high adsorption capacity, while iron electrodes produce Fe2+/Fe3+ ions leading to Fe(OH)2 and Fe(OH)3 species that promote sweep flocculation and enmeshment [5,7]. In the present study, aluminum electrodes were selected because of their superior electrochemical stability and higher coagulant generation efficiency under near-neutral pH conditions compared with iron [8,9]. The resulting aluminum hydroxide flocs (Al(OH)3) offer enhanced adsorption of colloidal and organic pollutants, generate less secondary sludge, and exhibit lower corrosion rates. These combined advantages justified the exclusive use of aluminum electrodes in this work.

A key challenge in electrocoagulation treatment, particularly for hospital wastewater, is the inconsistent removal of total dissolved solids (TDS) a parameter critical for effluent reuse. Previous studies applying EC to various wastewaters, including hospital and hypersaline effluents, have reported TDS removal in the range of 15–40%, depending on operating conditions and water chemistry [10,11]. Elevated TDS levels can impair aquatic ecosystems and limit potential reuse, highlighting the need for predictive models to understand and optimize treatment performance [12].

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) provides an efficient statistical framework for process optimization, but its predictive accuracy is limited when nonlinear interactions are dominant [13,14]. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), on the other hand, offer flexible, data-driven modeling capable of capturing nonlinear behavior [15,16]. Integrating RSM and ANN has proven to enhance both optimization and predictive performance in several wastewater treatment applications [17,18]. However, limited studies have focused exclusively on aluminum–aluminum (Al–Al) electrodes for hospital wastewater, and no prior work has developed a hybrid RSM–ANN framework to improve the prediction of TDS removal alongside turbidity and soluble chemical oxygen demand (sCOD). From a data-driven modeling perspective, the hybrid RSM–ANN approach links conventional statistical design with machine-learning prediction, enabling improved extraction of nonlinear relationships among operational variables [19,20]. This integration enhances both interpretability and predictive reliability, reflecting a growing convergence between environmental process modeling and information-based optimization. In this study, sCOD was selected as a key response variable instead of total COD, as it represents the dissolved and colloidal organic fraction that remains after primary sedimentation and is less affected by particulate matter. In hospital wastewater, this fraction better reflects persistent and bio-refractory organic pollutants originating from pharmaceuticals and disinfectants.

To fill this gap, the present study develops and validates a hybrid RSM–ANN modeling approach for electrocoagulation using Al–Al electrodes. The framework integrates the statistical interpretability of RSM with the nonlinear predictive capability of ANN to optimize key operating parameters (pH, current density, and electrolysis time) and evaluate pollutant removal efficiencies. The study aims to advance the understanding and optimization of electrocoagulation for complex hospital effluents and to support the design of compact, cost-effective systems suitable for decentralized wastewater treatment and sustainable effluent reuse.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hospital Wastewater

Hospital wastewater was collected from the influent collection tank of a teaching hospital and medical center located in Nakhon Nayok Province, Thailand. The facility accommodates approximately 500 inpatient beds and 1100 staff members. Grab samples were collected once a month during 2023–2024 to determine the physicochemical characteristics of the wastewater, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Physiochemical characteristics of hospital wastewater.

2.2. Electrocoagulation Unit

For the EC experiments, representative wastewater samples were separately collected from the same influent collection tank prior to the on-site treatment system. Grab samples were taken on the days of each batch experiment to ensure freshness and consistency of wastewater composition. All samples were immediately transported to the laboratory.

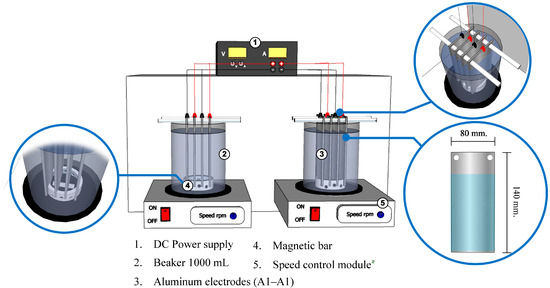

Experiments were conducted in batch mode using two identical cylindrical glass reactors (diameter 10 cm, height 20 cm, working volume 1.0 L each) operated in parallel as replicate units (Figure 1). For each run, 800 mL of wastewater were treated in each reactor, allowing sufficient headspace for floc formation. Both reactors were connected to a single direct current (DC) power supply (Meanwell 24 VDC 350 W 15 A, China).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the electrocoagulation experimental setup: (1) DC power supply, (2) two identical glass reactors operated in parallel as replicates, (3) aluminum electrodes (Al–Al) connected in monopolar–parallel arrangement within each reactor, (4) magnetic stirrer, and (5) speed control module.

Aluminum electrodes were exclusively employed in this study, selected based on well-established experimental and theoretical considerations. Al3+ ions rapidly hydrolyze to form amorphous Al(OH)3 flocs with high surface area, which promote effective adsorption and charge neutralization. Aluminum electrodes are also less prone to passivation under neutral pH, generate denser and more settleable sludge, and are widely available at low cost. These combined advantages justified the use of an Al–Al electrode configuration. Within each reactor, aluminum plates were installed as both anode and cathode (Al–Al configuration). Four flat plate electrodes were mounted per reactor, each with dimensions of 8 cm × 14 cm × 0.3 cm and an effective surface area of 96 cm2. The electrodes were connected in a monopolar–parallel arrangement to ensure uniform current distribution across the plates. The inter-electrode distance was fixed at 1.2 cm, and a locking holder maintained constant spacing and stable electrochemical conditions.

Continuous mixing was provided using a magnetic stirrer operating at 300 rpm to promote homogeneous dispersion and prevent particle settling. The electrical wiring and electrode placement ensured consistent voltage and current across both reactors. Operating two identical reactors in parallel for each run enhanced data reliability, reduced variability, and improved experimental reproducibility. Prior to each experiment, the aluminum electrodes were cleaned and prepared following a modified procedure adapted from previously reported protocols [21,22,23]. Each electrode was first rinsed with tap water followed by deionized water and then washed with absolute ethanol to remove surface contaminants and organic residues. The electrodes were subsequently dried in a hot-air oven at 103 °C for 1 h before use. This modified cleaning procedure ensured a clean and uniform electrode surface for consistent electrochemical reactions during all experimental runs.

2.3. Experimental Design

To systematically evaluate the effects of key operational parameters, a three-factor, three-level Box–Behnken design (BBD) within the RSM framework was adopted. The selected independent variables were initial pH (X1: 4–10), current density (X2: 5–25 mA/cm2), and electrolysis time (X3: 30–90 min), which are critical factors influencing electrocoagulation performance [6,7]. The experimental matrix was generated using the Design of Experiments (DOE) function in Minitab 17 software, comprised 15 runs including three replications at the center point to ensure model adequacy and reproducibility. All experiments were performed with aluminum electrodes (Al–Al configuration), while electrode spacing, reactor geometry, and mixing conditions were kept constant to isolate the effects of the studied variables. The coded and actual values of the variables are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Operating parameters range in their coded levels.

2.4. Analytical Methods

Samples were collected at both the beginning and end of each electrocoagulation run and were analyzed immediately to maintain consistency and reliability of the measurements. The pH values were measured using a calibrated digital pH meter (PH211, HANA Instrument Inc., Smithfield, RI, USA). Adjustment to the target pH level prior to each experiment was performed using either 0.1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) or 0.1 M sulfuric acid (H2SO4), depending on the required direction of adjustment. Wastewater characterization was performed following the standard methods for the examination of Water and Wastewater [24]. Specifically, turbidity was determined using the nephelometric method (Method 2130 B) with a Hach 2100P turbidimeter (Hach Company, Loveland, CO, USA). Total dissolved solids (TDS) and conductivity were measured using a handheld conductivity meter (YSI 60, YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, OH, USA) after pre-filtration through 0.45 µm membrane filters (Method 2540 C). Soluble chemical oxygen demand (sCOD) was analyzed by the closed reflux method (Method 5220 D) after filtration through a GF/C glass fiber filter to remove suspended solids. All measurements were conducted in triplicate, and average values were used for further analysis and model development. All measurements were performed in triplicate, and average values were reported. Quality assurance and control (QA/QC) procedures included reagent blank analysis, replicate testing, and periodic verification of instrument calibration to minimize analytical errors.

2.5. Statictical Analysis

The statistical significance of model terms was assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) at a 95% confidence level (p < 0.05). Model adequacy was evaluated based on the coefficient of determination (R2), adjusted R2. Diagnostic plots, including normal probability plots of residuals and residuals versus fitted values, were examined to verify the assumptions of normality, independence, and homoscedasticity. These diagnostic analyses confirmed that the residuals met the assumptions of normality, independence, and homoscedasticity, validating the adequacy of the regression models.

2.6. Modeling and Optimization Approach

2.6.1. RSM Modeling

RSM was employed to model and optimize the electrocoagulation process for hospital wastewater treatment. The experimental design was based on a three-factor, three-level BBD, as described in Section 2.3. The selected independent variables were initial pH, current density, and electrolysis time. These factors are known to significantly influence the generation of coagulant species, destabilization of pollutants, and overall treatment kinetics. The coded experimental data were used to develop second-order polynomial regression models for each response variable, including turbidity, sCOD, and TDS removal. The generalized form of the regression equation is expressed as:

where Yi is the predicted response, Xi and Xj are the coded independent variables, β0 is the intercept, βi, βii, and βij are the linear, quadratic, and interaction coefficients, respectively, k and C are the number of factors and the residual terms, respectively.

2.6.2. ANN Modeling

ANN modeling was performed using the Program WEKA Version 3.8.4 (University of Waikato, New Zealand) to predict the removal efficiencies of the three responses. ANN is a computational model inspired by biological neural networks and consists of three interrelated layers: the input layer, hidden layer(s), and output layer. The network was constructed with three input neurons corresponding to initial pH, current density, and electrolysis time, and three output neurons representing the target responses. Prior to model training, all input and output data were normalized within the range of 0 to 1. To identify the most appropriate ANN architecture, several configurations with varying numbers of hidden layers and neurons were tested. The network architecture was kept deliberately simple, consisting of a single hidden layer with a limited number of neurons, to minimize the risk of overfitting given the small dataset (n = 15).

Model performance was evaluated using root mean square error (RMSE) and validation error obtained from 3-fold cross-validation. The configuration with the lowest total error across all responses was selected as the optimal structure for subsequent predictions. To ensure model robustness and reliable performance evaluation, a 3-fold cross-validation approach was employed. The 15-run dataset was randomly divided into three equal subsets (five samples each). In each fold, one subset was used for testing, one for validation, and the remaining one for training. The process was repeated three times so that every sample was used once for testing and once for validation. The average values of R2, RMSE, and MAPE across the three folds were used to evaluate model performance and ensure reproducibility. The network was trained using the Backpropagation algorithm due to its efficiency in handling nonlinear systems and small-to-medium-sized datasets. Model performance was assessed using standard statistical indicators, including R2, mean squared error (MSE), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE). The ANN predictions were compared with the RSM results to evaluate the relative accuracy and modeling strength of each approach. While RSM was employed for experimental design and initial modeling, ANN was subsequently applied to the same dataset to enhance prediction accuracy and capture complex nonlinear patterns that are not fully described by the quadratic regression equations. This sequential modeling strategy leverages the strengths of both techniques, enabling both interpretability (via RSM) and precision (via ANN). This validation process ensured model robustness and generalization capability, reducing the potential for overfitting and confirming the reliability of ANN predictions.

2.7. Calculation of Electrode and Energy Consumption

The operational cost of an electrocoagulation system is primarily influenced by energy and electrode consumption. In this study, both parameters were estimated to evaluate the overall cost-effectiveness of the process. The energy consumption per unit volume of treated water was calculated using the following equation [4,25]:

where represents the amount of energy consumed (kWh/m3), U represents the applied voltage, I denote the electrical current (A), refers to the reaction time (hours), is the volume of water used (m3).

According to Faraday’s law theoretically the mass of the electrodes dissolves during the process can be calculated using Equation (3):

where denotes the amount of electrode material used (kg/m3), represents the molecular weight of Al (26.98), is the number of electrons involved in the oxidation/reduction reaction ( = 3 for Al), and F is Faraday’s constant (96,487 C/mole).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of Raw Hospital Wastewater

The influent exhibited a slightly acidic pH of 6.73 ± 0.61 and relatively high electrical conductivity (974.43 ± 171.76 µS/cm), suggesting a considerable presence of dissolved ionic species. The average temperature was 26.70 ± 1.42 °C, while the measured alkalinity was 280.00 ± 4.62 mg/L. Substantial pollutant concentrations were observed across several key parameters. Turbidity was recorded at 152.69 ± 84.91 NTU, and TSS and TDS were measured at 80.50 ± 43.44 mg/L and 725.33 ± 538.15 mg/L, respectively. The organic content of the wastewater was notably high, with BOD at 140.83 ± 108.54 mg/L and COD at 569.33 ± 443.04 mg/L. These values substantially exceed the permissible limits set by Thailand’s national wastewater discharge standards [26], particularly in terms of COD and TDS. The high levels of turbidity, organic matter, and dissolved solids reflect the complex and variable composition of hospital wastewater. These characteristics are typically associated with the presence of pharmaceutical residues, disinfectants, nutrients, and metabolic by-products from medical care activities [2,27]. High concentrations of COD and TDS are particularly problematic, as they are known to inhibit microbial metabolism and destabilize microbial communities, thereby compromising the performance of conventional biological treatment systems. The BOD/COD ratio of the hospital wastewater was calculated to be approximately 0.25, indicating low biodegradability. Ratios below 0.4 are widely regarded as unfavorable for biological treatment, as they suggest a dominance of slowly degradable or non-biodegradable organic compounds [28]. These findings underscore the need for alternative treatment approaches that are less reliant on microbial activity. EC represents a promising physicochemical alternative for hospital wastewater treatment, capable of removing a broad spectrum of pollutants through electrochemically induced coagulation and flotation. The fundamental mechanism of EC using aluminum electrodes is described in the following subsection.

Electrocoagulation Mechanism

The EC process using aluminum electrodes involves a combination of anodic dissolution, cathodic hydrogen evolution, and subsequent hydrolysis of aluminum ions to form coagulant species. The key electrochemical reactions are summarized below [29].

At the anode: Al (s) ⟶ Al3+ + 3e−

At the cathode: 2H2O + 2e− ⟶ H2 (g) + 2OH−

Overall hydrolysis and coagulation reactions:

Al3+ + 3H2O ⟶ Al(OH)3 (s) + 3H+

The freshly generated Al3+ ions hydrolyze to form amorphous aluminum hydroxide flocs (Al(OH)3), which act as active coagulants to destabilize colloidal and suspended particles through charge neutralization, adsorption, and sweep flocculation. Meanwhile, hydrogen gas evolution at the cathode promotes the flotation of aggregated flocs to the surface, facilitating their subsequent separation. The overall removal mechanism is therefore a combination of electrochemical oxidation, coagulation, and flotation, resulting in efficient elimination of turbidity, organic matter, and dissolved pollutants from wastewater [4,5,6].

3.2. Box–Behnken Design and Experimental Outcomes

Electrocoagulation experiments were conducted using a BBD including 15 runs to investigate the interactive effects of initial pH, current density, and electrolysis time on the removal of turbidity, soluble sCOD, and TDS. The corresponding removal efficiencies are summarized in Table 3. The highest removal efficiencies achieved were 99.1% for turbidity, 74.0% for sCOD, and 46.7% for TDS, demonstrating the capability of electrocoagulation to treat hospital wastewater under optimized conditions. Treatment performance varied across runs, highlighting the differential sensitivities of each pollutant to operational variables. Turbidity removal was consistently high, while sCOD removal showed greater variability. In contrast, TDS removal remained relatively modest, reflecting the inherent difficulty in eliminating dissolved ionic species via coagulation mechanisms.

Table 3.

Experimental design matrix and response based on actual and expected turbidity, sCOD, and TDS (%) values suggested by BBD.

The individual effects of current density, electrolysis time, and initial pH on pollutant removal were examined to elucidate the conventional experimental trends. An increase in current density generally enhanced turbidity and sCOD removal due to greater Al3+ generation and subsequent coagulant formation, although excessively high current densities increased energy demand without providing proportional improvement [6,11]. Extending electrolysis time improved pollutant removal as additional coagulant species were produced and floc maturation occurred; however, beyond 75–90 min, the improvement plateaued, indicating diminishing returns [4]. The initial pH also exerted a strong influence on coagulant speciation: near-neutral pH provided optimal performance owing to the predominance of amorphous Al(OH)3 species, whereas acidic conditions favored soluble Al3+ and alkaline conditions favored Al(OH)4−, both of which reduced coagulation efficiency [5]. These observations are consistent with previous studies [4] and confirm that optimal pollutant removal occurs under moderate current density, sufficient electrolysis duration, and near-neutral pH.

3.3. RSM and ANN Model Development and Comparison

To capture both linear interactions and nonlinear behavior in electrocoagulation performance, this study employed a hybrid modeling framework combining RSM and ANN. RSM was applied first to design experiments using the BBD and to identify significant factor interactions through second-order polynomial models. While RSM provides interpretability and efficiency in experimental design, its predictive capability is constrained when responses exhibit strong nonlinear patterns. To address this limitation, ANN modeling was applied to the same dataset, offering flexible learning and improved accuracy, particularly for TDS. Together, these complementary approaches form a hybrid framework that integrates statistical interpretability with machine-learning precision.

3.3.1. Polynomial Regression and ANOVA Analysis

Second-order polynomial regression models were developed to evaluate the effects of initial pH, current density, and electrolysis time on pollutant removal. The fitted equations for turbidity, sCOD, and TDS removal efficiencies are shown in Equations (7)–(9)

Turbidity removal (%) ∛Y = 966,629 − 7183 X1 − 3124 X2 + 109,254 X3 − 91,365 X1 × X1 − 22,291 X2 × X2 − 141,845 X3 × X3 − 34,087 X1 × X2 − 159,219 X1 × X3 − 18 X2 × X3

sCOD removal (%) Y = 31.81 − 0.93 X1 + 7.29 X2 + 2.86 X3 − 22.87 X1 × X1 − 3.37 X2 × X2 − 1.95 X3 × X3 + 0.27 X1 × X2 − 5.77 X1 × X3 + 1.17 X2 × X3

TDS removal (%) Y = 11.000 + 1.010 X1 + 0.520 X2 + 10.560 X3 + 1.890 X1 × X1 − 12.390 X2 × X2 − 10.970 X3 × X3 + 6.770 X1 × X2 − 4.150 X1 × X3 − 3.600 X2 × X3

The statistical significance and adequacy of each regression model were evaluated using analysis of variance (ANOVA). As summarized in Table 4, all models were significant at the 95% confidence level (p < 0.05). Turbidity removal exhibited the strongest fit (R2 = 0.959), with current density, electrolysis time, and the pH–time interaction identified as significant factors. The sCOD model also showed strong adequacy (R2 = 0.900), mainly influenced by pH and current density, including its quadratic effect. The TDS model demonstrated lower predictability (R2 = 0.856), dominated by electrolysis time and its quadratic term. These results highlight that while the regression models captured key factor interactions, their reduced accuracy for TDS reflects the inherent complexity of dissolved solids behavior in electrocoagulation systems.

Table 4.

ANOVA results for turbidity, sCOD, and TDS removal (Significant at p < 0.05).

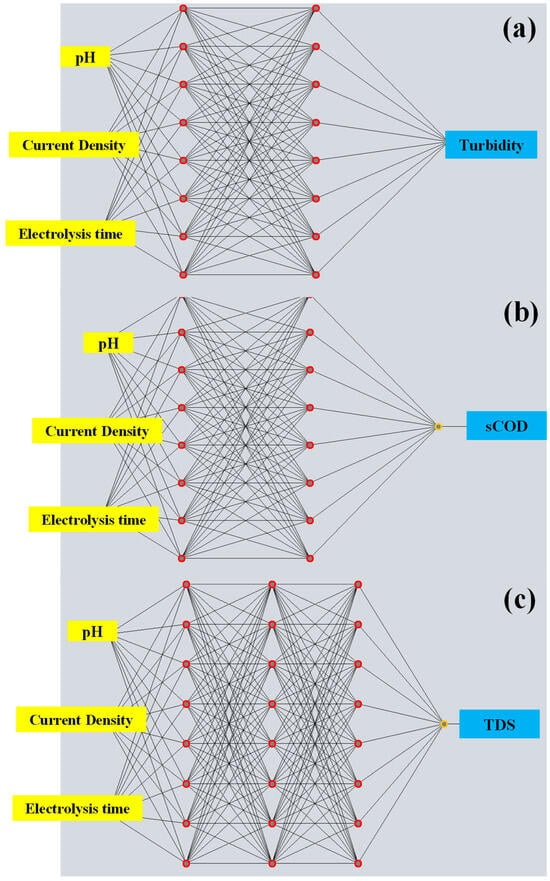

3.3.2. ANN Model Structure and Performance

While RSM is widely applied for experimental design and optimization, its predictive performance might be limited in the presence of complex nonlinear interactions between variables. To address these limitations, ANN models were developed and trained using the same experimental dataset to evaluate their ability to predict removal efficiencies of turbidity, sCOD, and TDS. The predictive accuracies of both models were compared using statistical indicators such as R2 and RMSE. The architectures of the optimized ANN models are illustrated in Figure 2a–c. Each model was trained using three input variables initial pH, current density, and electrolysis time and tuned by trial and error to minimize prediction errors. The ANN models were constructed using a multilayer perceptron (MLP) architecture trained on 15 experimental data points obtained from the Box–Behnken design. The Levenberg–Marquardt backpropagation algorithm was employed as the training method, with a sigmoid transfer function applied in the hidden layer and a linear activation function in the output layer. Several network configurations were tested as described in Section 2.6, and the one yielding the lowest mean squared error (MSE) was selected as the optimal model structure. As summarized in Table 5, the ANN models demonstrated excellent statistical performance in both training and testing phases. For turbidity and sCOD, the models achieved perfect fit during training (R2 = 1.00), with low RMSE values of 0.32 and 0.54, respectively. Testing performance also remained robust, with RMSE values of 6.1% for turbidity and 8.05% for sCOD. The TDS model exhibited slightly lower accuracy (R2 = 0.98; RMSE = 3.82 in training and 21.62 in testing) yet still outperformed the corresponding RSM model. These results confirm that ANN models were capable of capturing both linear and nonlinear relationships effectively, even with the relatively small experimental dataset.

Figure 2.

Optimized artificial neural network (ANN) architectures for predicting removal efficiencies in the electrocoagulation process using Al–Al electrodes: (a) turbidity, (b) soluble chemical oxygen demand (sCOD), and (c) total dissolved solids (TDS).

Table 5.

ANN model details.

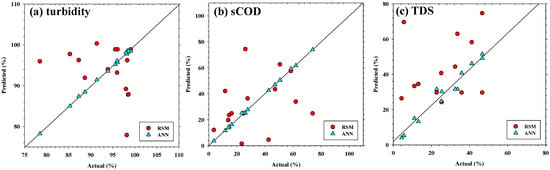

3.3.3. Model Comparison and Interpretation

Comparative analysis revealed that the ANN model consistently outperformed the RSM model in predictive accuracy, particularly for TDS. Both models yielded strong agreement for turbidity and sCOD; however, RSM tended to misestimate performance under low or variable removal, whereas ANN followed the experimental trends more closely. Scatter plots of actual versus predicted values (Figure 3) illustrate the closer alignment of ANN outputs with the experimental data compared with RSM.

Figure 3.

Scatter plots of actual versus predicted values for (a) turbidity, (b) sCOD, and (c) TDS removal efficiencies. Data points from RSM (○) and ANN (△) are shown against the 1:1 reference line. ANN exhibited closer alignment with experimental data, particularly for TDS, indicating superior predictive accuracy.

Quantitative analysis further confirmed the superior predictive performance of the ANN models compared with the RSM models. As shown in Table 5 and Figure 3, the ANN achieved markedly higher coefficients of determination (R2 values greater than 0.97 for all responses) and substantially lowered root mean square error (RMSE) values. For instance, the prediction accuracy for TDS increased from an R2 of 0.856 with RSM to 0.982 with ANN, accompanied by an approximately 45% reduction in RMSE. Similar improvements were observed for turbidity and sCOD, indicating that the neural-network-based model provided more stable and generalized predictions across the limited experimental dataset. These results highlight the capability of ANN to capture complex nonlinear interactions that quadratic regression models cannot fully represent, thereby enhancing the overall reliability of the hybrid RSM–ANN framework.

The superior predictive ability of ANN is attributed to its flexibility in capturing nonlinear and threshold-type behaviors that are not adequately represented by quadratic polynomial equations. RSM was effective in identifying significant factors and capturing linear or moderate quadratic effects, which explains its strong fit for turbidity and sCOD. However, TDS removal is influenced by ionic strength, electrostatic shielding, and complex flocculation dynamics, which generate nonlinear interactions beyond the capacity of second-order models. ANN, through hidden-layer learning, accommodates such complexity without assuming a fixed functional form, thereby achieving higher predictive accuracy and robustness.

These findings are consistent with recent studies demonstrating that hybrid RSM–ANN frameworks provide superior performance in modeling and optimizing electrocoagulation and other advanced treatment processes [15,16]. The present results reinforce the complementary role of RSM and ANN: RSM enhances interpretability and factor analysis, while ANN improves nonlinear prediction, particularly for challenging parameters such as TDS. Although the ANN achieved high predictive accuracy, it is important to recognize that the relatively small dataset (n = 15) may restrict the model’s generalizability. To mitigate potential overfitting, the network architecture was intentionally kept simple, consisting of a single hidden layer with a limited number of neurons. In addition, 3-fold cross-validation was applied to ensure that each data subset was used for both training and testing, enhancing model robustness and reducing bias. Consequently, the ANN predictions should be regarded as indicative of the model’s potential performance rather than as universally generalizable outcomes. Despite the promising outcomes, several limitations should be acknowledged. The experimental dataset comprised only 15 runs from a Box–Behnken design, restricting the training sample size for ANN modeling. A 3-fold cross-validation scheme was employed to maximize data utilization; however, the small dataset may lead to overfitting and overly optimistic estimates of predictive accuracy, particularly for nonlinear responses such as TDS. Therefore, the ANN results should be interpreted as indicative rather than fully generalizable.

Future work should include larger datasets obtained from extended experimental campaigns or pilot-scale trials, enabling the use of more robust validation strategies such as repeated k-fold cross-validation, leave-one-out CV (cross-validation), or bootstrap resampling. These approaches will reduce bias, enhance model reliability, and strengthen the hybrid RSM–ANN framework for real-world applications. From an informational perspective, this hybrid RSM–ANN framework exemplifies how data-driven learning can complement statistical modeling to support intelligent decision-making in complex environmental systems. By integrating interpretability with predictive intelligence, it contributes to the broader development of information-based optimization and environmental informatics.

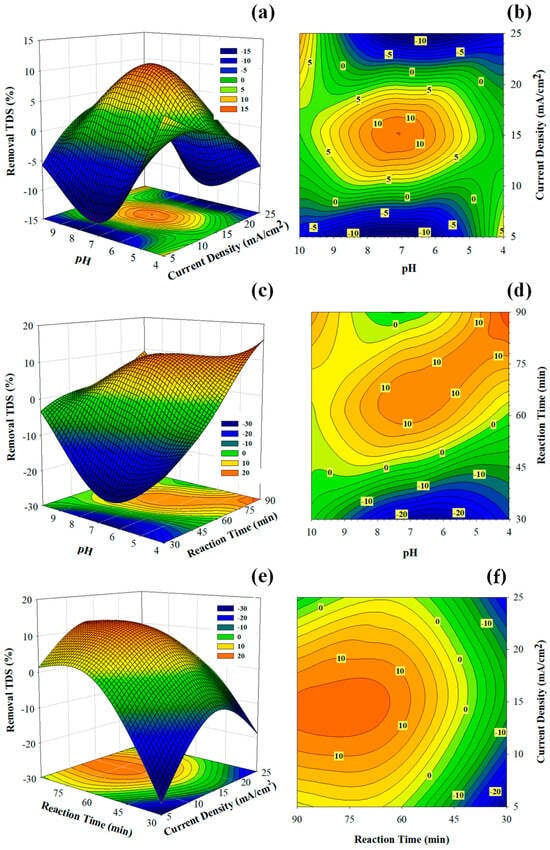

3.4. Model Validation and Optimization

A numerical optimization was conducted to maximize turbidity, sCOD, and TDS removal. The optimal conditions were an initial pH of 7.0, a current density of 20 mA/cm2, and an electrolysis time of 75 min. The model predicted removals of 95.9% for turbidity, 72.4% for sCOD, and 20.6% for TDS. Experimental validation under these conditions achieved 94.5 ± 2.3% for turbidity, 69.8 ± 3.1% for sCOD, and 19.1 ± 2.8% for TDS, with relative errors below 8% (Table 6). These results confirm that the RSM models adequately represented the system and provided a balanced trade-off between removal efficiency and energy consumption. Response surface and contour plots (Figure 4) illustrated the interaction effects of operating parameters on TDS removal. TDS removal improved with increasing current density and electrolysis time, particularly under near-neutral pH, highlighting the nonlinear relationships captured by the hybrid modeling approach.

Table 6.

Comparison of predicted and observed removal efficiencies under optimal conditions.

Figure 4.

Response surface and contour plots showing the interactive effects of process variables on TDS removal efficiency: (a,b) pH and current density, (c,d) pH and electrolysis time, and (e,f) current density and electrolysis time. Color gradients represent the TDS removal efficiency (%), with warmer colors (orange/red) indicating higher removal and cooler colors (green/blue) indicating lower removal. The plots highlight the nonlinear behavior of TDS removal and the importance of simultaneous parameter adjustment under near-neutral pH for achieving optimized performance.

The moderate TDS removal observed in this study (19.1–46.7%) is comparable to values reported in previous electrocoagulation studies treating hospital or pharmaceutical wastewaters, typically ranging from 15% to 50% depending on electrode type, pH, and ionic composition. Mahajan et al. (2013) achieved approximately 30% TDS removal using Al electrodes for hospital effluent [30], while Esfandyari et al. (2019) reported 40–45% under optimized conditions for cefazolin-containing wastewater [31]. These findings confirm that electrocoagulation is more efficient for turbidity and organic-matter removal than for dissolved solids, as ionic species are less affected by charge neutralization and floc formation. Nevertheless, partial TDS reduction remains valuable for improving effluent quality and facilitating non-potable reuse. In decentralized hospital settings, such reductions can lower salinity, minimize scaling potential, and improve compatibility with downstream polishing processes such as membrane filtration or ion exchange, thereby enhancing the overall sustainability of water reuse schemes.

Scaling up from the 0.8 L bench reactors to pilot or full-scale hospital units may present challenges related to hydraulic mixing, current distribution, electrode passivation, and sludge handling. Nevertheless, the low energy demand of 0.34 kWh/m3 suggests favorable economic feasibility when proper maintenance protocols are applied. In real hospital settings, wastewater composition varies due to disinfectant use and dialysis effluents, underscoring the need for adaptive control. Hybrid RSM–ANN modeling could support real-time adjustment of operating parameters and stabilize performance under fluctuating influent quality. Electrocoagulation can also serve as a pretreatment step to protect downstream biological or membrane systems. Pilot-scale trials remain essential to validate robustness, electrode lifetime, and sludge management under practical conditions.

The treatment performance achieved in this study was comparable to or higher than those reported in previous electrocoagulation studies for hospital and industrial effluents. For example, Hakizimana et al. (2017) reported turbidity and COD removals of 90–95% and 70–80%, respectively, under similar current density ranges [4], while Deshpande et al. (2012) observed 60–70% COD removal in pharmaceutical wastewater using Al–Fe electrodes [32]. Mahajan et al. (2013) achieved 92% turbidity and 75% COD removal from hospital operation-theatre effluent using Al–Fe electrodes [30], whereas Esfandyari et al. (2019) reported 68% COD removal and effective cefazolin elimination from hospital wastewater at pH 7 and 15 mA/cm2 [31]. The present study achieved up to 99.1% turbidity and 74.0% sCOD removal at lower energy consumption (0.34 kWh m−3), demonstrating the high efficiency of the Al–Al configuration under optimized conditions. Compared with advanced oxidation processes such as ozonation, photocatalysis, and plasma-based oxidation systems [33,34,35,36], as well as membrane bioreactors [37], electrocoagulation offers simpler operation, lower energy requirements, and minimal chemical input, making it particularly attractive for decentralized hospital wastewater treatment. The hybrid RSM–ANN modeling approach further enhances process optimization and predictive reliability, providing a valuable framework for scaling up EC systems in practical applications. Overall, the optimized Al–Al EC system guided by hybrid modeling shows promise as a scalable and cost-effective solution for decentralized hospital wastewater treatment, particularly in resource-limited regions.

3.5. Electrode and Energy Consumption

Under optimized conditions, the EC process consumed 0.34 kWh/m3, corresponding to an estimated bench-scale energy cost of US $0.033 per m3 at the average electricity rate for Thai hospital facilities (US $0.09 per kWh). Although this estimate is based on laboratory-scale operation, it highlights the economic advantage achievable through optimized Al–Al electrocoagulation. The energy demand is notably lower than that reported in previous electrocoagulation studies (0.5–2.5 kWh/m3, depending on operational settings) [4] and remains comparable with conventional biological treatment processes (0.3–0.8 kWh/m3) [22]. It is also competitive with advanced alternatives, including membrane bioreactors (0.7–1.5 kWh/m3) and ozonation (>1.0 kWh/m3) [23,24]. Aluminum consumption ranged from 1.68 × 10−7 to 2.80 × 10−7 kg/m3 across runs, indicating that both energy and material requirements were modest while still achieving high pollutant removal efficiencies. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that Al–Al EC can satisfy both performance and cost-effectiveness criteria, making it especially attractive for decentralized hospital wastewater facilities where operational costs are a critical concern. Beyond technical feasibility, the study highlights the broader relevance of aluminum-based EC in advancing Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6.3 by reducing pollutant discharges and SDG 12.2 through improved reuse potential. The approach also resonates with Thailand’s national circular water management strategy, which emphasizes effluent reuse and resource recovery. While feasibility has been established at the laboratory scale (TRL 3–4), pilot-scale validation (TRL 5–6) will be essential to assess robustness under variable wastewater conditions, confirm long-term electrode stability, and address sludge management options. Integration with downstream processes such as membrane bioreactors or reverse osmosis could further enhance effluent quality and water reuse opportunities. Policy support particularly through hospital-based pilot projects and clear guidelines for sludge handling will be vital to accelerate adoption. Overall, the RSM–ANN-guided EC framework provides not only a scientific contribution but also a practical pathway toward decentralized and sustainable hospital wastewater management.

4. Conclusions

This study established a hybrid RSM–ANN modeling framework for optimizing electrocoagulation (EC) with aluminum–aluminum (Al–Al) electrodes in hospital wastewater treatment. The integration of response surface methodology and artificial neural networks enabled both the interpretability of key factor interactions and the enhanced nonlinear predictive capability, particularly for complex parameters such as TDS. This dual modeling approach provided a robust analytical tool to optimize operational conditions and deepened the understanding of EC behavior under variable wastewater compositions.

From a practical perspective, the optimized Al–Al EC process demonstrated energy-efficient and technically feasible performance, supporting its potential application in decentralized hospital wastewater treatment systems. The approach offers a low-chemical, low-energy pathway that aligns with sustainable water reuse and circular economy principles, making it suitable for small and resource-limited healthcare facilities.

Future research should focus on pilot-scale implementation to validate long-term performance, electrode stability, and sludge management, as well as on integrating hybrid RSM–ANN modeling into real-time control and adaptive optimization systems. Such developments will advance the practical deployment of EC technology and strengthen its role as a reliable component of sustainable wastewater management in the healthcare sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T. (Suthida Theepharaksapan) and K.M.; methodology, Y.L.; software, A.K. and S.P.; validation, Y.L., A.K. and S.P.; investigation, R.P. and S.T. (Suchira Thongson); resources, R.P. and S.T. (Suchira Thongson); data curation, S.T. (Suthida Theepharaksapan) and K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.T. (Suthida Theepharaksapan) and K.M.; writing—review and editing, S.T. (Suthida Theepharaksapan) and K.M.; visualization, S.P. and S.T. (Suchira Thongson). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Fundamental Fund (Grant No. 127/2567), provided through Srinakharinwirot University under the program of Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to the staff and management of the participating hospital in Nakhon Nayok Province, Thailand for their kind cooperation and assistance during sample collection. Special thanks are extended to the Environmental Engineering Laboratory, Faculty of Engineering, Srinakharinwirot University, for providing laboratory facilities and technical support throughout the experimental work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Funding statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Zhang, X.; Yan, S.; Chen, J.; Tyagi, R.D.; Li, J. 3-Physical, Chemical, and Biological Impact (Hazard) of Hospital Wastewater on Environment: Presence of Pharmaceuticals, Pathogens, and Antibiotic-Resistance Genes. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Tyagi, R.D., Sellamuthu, B., Tiwari, B., Yan, S., Drogui, P., Zhang, X., Pandey, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 79–102. ISBN 978-0-12-819722-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ajala, O.J.; Tijani, J.O.; Salau, R.B.; Abdulkareem, A.S.; Aremu, O.S. A Review of Emerging Micro-Pollutants in Hospital Wastewater: Environmental Fate and Remediation Options. Results Eng. 2022, 16, 100671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.H.; Gin, K.Y.-H. Occurrence and Removal of Pharmaceuticals, Hormones, Personal Care Products, and Endocrine Disrupters in a Full-Scale Water Reclamation Plant. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 599–600, 1503–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakizimana, J.N.; Gourich, B.; Chafi, M.; Stiriba, Y.; Vial, C.; Drogui, P.; Naja, J. Electrocoagulation Process in Water Treatment: A Review of Electrocoagulation Modeling Approaches. Desalination 2017, 404, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, M.; Katoch, S.S.; Kadier, A.; Singh, A. A Review on Electrocoagulation Process for the Removal of Emerging Contaminants: Theory, Fundamentals, and Applications. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 15252–15281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Suhan, M.B.K.; Islam, M.S. Recent Advances and Perspective of Electrocoagulation in the Treatment of Wastewater: A Review. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2022, 17, 100643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, M.; Das, P.P.; Purkait, M.K. A Review on the Treatment of Water and Wastewater by Electrocoagulation Process: Advances and Emerging Applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phu, T.K.C.; Nguyen, P.L.; Phung, T.V.B. Recent Progress in Highly Effective Electrocoagulation-Coupled Systems for Advanced Wastewater Treatment. iScience 2025, 28, 111965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegladza, I.; Xu, Q.; Xu, K.; Lv, G.; Lu, J. Electrocoagulation Processes: A General Review about Role of Electro-Generated Flocs in Pollutant Removal. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 146, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emamjomeh, M.M.; Muttucumaru, S. Review of Pollutants Removed by Electrocoagulation and Electrocoagulation/Flotation Processes. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1663–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasim, M.A.; AlJaberi, F.Y.; Alardhi, S.M.; Salman, A.D.; Hathal, M.M.; Cretescu, I.; Vargas, A.R. Enhancing the Removal of Total Dissolved Solids from Petroleum Wastewater through Electrocoagulation. Eng. Technol. J. 2025, 43, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D.V. Water Quality Assessments: A Guide to the Use of Biota, Sediments and Water in Environmental Monitoring, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-419-21590-5. [Google Scholar]

- Nazlabadi, E.; Niaragh, E.K.; Moghaddam, M.R.A. A Systematic and Critical Review of Two Decades’ Application of Response Surface Methodology in Biological Wastewater Treatment Processes. Desalination Water Treat. 2021, 228, 92–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, A.; Chen, L.; Mao, X. Response Surface Methodology for Process Optimization in Livestock Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Hu, J.; Cao, R.; Ruan, W.; Wei, X. A Review on Experimental Design for Pollutants Removal in Water Treatment with the Aid of Artificial Intelligence. Chemosphere 2018, 200, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Aani, S.; Bonny, T.; Hasan, S.W.; Hilal, N. Can Machine Language and Artificial Intelligence Revolutionize Process Automation for Water Treatment and Desalination? Desalination 2019, 458, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, M.S.; Vegad, K.G.; Shah, K.A.; Hassan, A.A. An Artificial Neural Network Combined with Response Surface Methodology Approach for Modelling and Optimization of the Electro-Coagulation for Cationic Dye. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, D.; Arivazhagan, M. An Integrated (Electrocoagulation and Adsorption) Approach for the Treatment of Textile Industrial Wastewater: RSM and ANN Based Optimization. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 235, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfghi, F.M. A Hybrid Statistical Approach for Modeling and Optimization of RON: A Comparative Study and Combined Application of Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Based on Design of Experiment (DOE). Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2016, 113, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awolusi, T.F.; Oke, O.L.; Akinkurolere, O.O.; Atoyebi, O.D. Comparison of Response Surface Methodology and Hybrid-Training Approach of Artificial Neural Network in Modelling the Properties of Concrete Containing Steel Fibre Extracted from Waste Tyres. Cogent Eng. 2019, 6, 1649852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.; Chen, C.-F.; Robles, D.J.; Rhodes, C.; Mukherjee, P.P. Non-Aqueous Electrode Processing and Construction of Lithium-Ion Coin Cells. J. Vis. Exp. 2016, 118, e53490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, D.; Mirica, A.-C.; Iosub, R.; Stan, D.; Mincu, N.B.; Gheorghe, M.; Avram, M.; Adiaconita, B.; Craciun, G.; Bocancia Mateescu, A.L. What Is the Optimal Method for Cleaning Screen-Printed Electrodes? Processes 2022, 10, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Ruck, M. A Stable Porous Aluminum Electrode with High Capacity for Rechargeable Lithium-Ion Batteries. Batteries 2023, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 23rd ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Volume 53, p. 1699. ISBN 978-0-87553-287-5. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, P.K.; Barton, G.W.; Mitchell, C.A. The Future for Electrocoagulation as a Localised Water Treatment Technology. Chemosphere 2005, 59, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanapiya, P.; Tantisattayakul, T. Wastewater Reclamation Trends in Thailand. Water Sci. Technol. 2022, 86, 2878–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlicchi, P.; Al Aukidy, M.; Zambello, E. What Have We Learned from Worldwide Experiences on the Management and Treatment of Hospital Effluent? An Overview and a Discussion on Perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 514, 467–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf & Eddy Inc.; Tchobanoglous, G.; Stensel, H.; Tsuchihashi, R.; Burton, F. Wastewater Engineering: Treatment and Resource Recovery, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mechelhoff, M.; Kelsall, G.H.; Graham, N.J.D. Electrochemical Behaviour of Aluminium in Electrocoagulation Processes. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2013, 95, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, R.; Khandegar, V.; Saroha, K. Treatment of Hospital Operation Theatre Effluent by Electrocoagulation. Int. J. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2013, 4, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Esfandyari, Y.; Saeb, K.; Tavana, A.; Rahnavard, A.; Fahimi, F.G. Effective Removal of Cefazolin from Hospital Wastewater by the Electrocoagulation Process. Water Sci. Technol. 2019, 80, 2422–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, A.M.; Ramakant, N.; Satyanarayan, S. Treatment of Pharmaceutical Wastewater by Electrochemical Method: Optimization of Operating Parameters by Response Surface Methodology. J. Hazard. Toxic Radioact. Waste 2012, 16, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indah Dianawati, R.; Endah Wahyuningsih, N.; Nur, M. Treatment of Hospital Waste Water by Ozone Technology. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1025, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, A.; Assadi, A.A.; El Jery, A.; Badawi, A.K.; Kenfoud, H.; Baaloudj, O.; Assadi, A.A. Advanced Photocatalytic Treatment of Wastewater Using Immobilized Titanium Dioxide as a Photocatalyst in a Pilot-Scale Reactor: Process Intensification. Materials 2022, 15, 4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, B.R.; Sato, M.; Sunka, P.; Hoffmann, M.R.; Chang, J.-S. Electrohydraulic Discharge and Nonthermal Plasma for Water Treatment. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 882–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theepharaksapan, S.; Matra, K. Atmospheric Argon Plasma Jet for Post-Treatment of Biotreated Landfill Leachate. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Electrical Engineering Congress (iEECON), Krabi, Thailand, 7–9 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, F.; Tan, X.; Zheng, X.; Cheng, R. Global Techno-Economic Analysis of MBR for Hospital Wastewater Treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 956, 177172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).