1. Introduction

Water supply systems often rely on disinfectant residuals to ensure water quality through the network. Free chlorine residual is the most widely adopted disinfectant residual in drinking water supply systems. According to the World Health Organization, the minimum residual concentration of free chlorine at the point of delivery should be 0.2 mg/L [

1]. High chlorine levels are associated with issues such as odor/taste problems or disinfection by-product formation (e.g., [

2]). Consequently, residual chlorine ranges between 0.2 and 5 mg/L [

3] but is most often kept below 1–1.5 mg/L in practice [

4].

To ensure adequate chlorine values, free chlorine is commonly measured at strategic points within the supply network and/or at the user tap. Online monitoring presents several advantages [

5], but continuous chlorine analyzers are expensive and require systematic maintenance [

6]. In practice, many chlorine monitoring plans still mainly rely on manual grab samples, especially in small urban or rural areas. Chlorine sampling at the water distribution system is basically conceived for quality assurance, and few utilities employ a systematic protocol to collect samples [

7]. Previous authors have highlighted that sampling procedures could and should be improved beyond regulatory compliance to gain knowledge about network operation [

8]. This would be especially interesting to better characterize (and model) the chlorine decay process, which is known to be complex [

9].

Chlorine decay is usually divided into a bulk and a wall decay component (e.g., [

10,

11]). Bulk decay is determined by water quality characteristics only and is not influenced by the pipes within the water distribution system [

12]. It is usually characterized at the entrance to the water distribution network through bottle tests [

13,

14]. Bottle tests involve measuring chlorine evolution over time in a laboratory environment to adjust the equation coefficients that describe the observed decay [

15]. Different models can be adopted to simulate bulk decay [

16,

17], but first-order models (i.e., exponential decay) are most typically assumed (e.g., [

9,

18,

19]). This implies that a single parameter, commonly known as the bulk decay coefficient or

, must be adjusted. This coefficient varies widely depending on the water source and temperature [

18,

20]. Wall decay refers to the chlorine reaction with the wall. This includes chlorine interaction with biofilms, corrosion products, and/or any other particles adhered to the wall [

17], which may vary in space and time in the water distribution network. Different models have been presented to explain the wall component (e.g., [

18,

21,

22]), but there is still no consensus on which is the best alternative to simulate this complex interaction. In practice, wall decay is often quantified as the difference between measurements of chlorine at a network position and the corresponding values obtained when assuming a bulk-decay (only) model [

17,

23]. This means that an accurate estimation of bulk decay is also key to characterizing the wall effect [

16].

Despite the relevance of chlorine decay for the operation of water supply systems, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no previous studies have assessed the impact of chlorine measurement errors on

estimation. This can be problematic because several sources of error coexist when sampling free chlorine [

24]. For example, measurement error is affected to some extent by the measurement principle. Either colorimetric methods (measurement of color intensity after applying a reaction product) or amperometric methods (measurement of ions based on electric current or changes in electric current) can be used to measure chlorine. DPD (N,N-diethyl-p-phenylenediamine) or colorimetric methods have typically been the most popular choice for free chlorine measurement (e.g., [

5,

25,

26]) because they are less expensive; however, measurements may be subject to significant measurement errors and/or low repeatability among users [

24]. Although less common, disposable sensor amperometry tests—such as those performed with Chlorosense or KEMIO devices [

27]—are increasingly being adopted for grab sampling in the water supply (e.g., [

28,

29,

30]) and food (e.g., [

31,

32]) industries. Previous studies have identified that LaMotte colorimeters (based on colorimetry) and Chlorosense devices (based on chronoamperometry) are associated with 5.1% [

24] and 4.8% [

26] measurement errors, respectively, under laboratory conditions. Water quality measurement errors (in general) have motivated the measurement of some parameters (such as coliforms) more than once (e.g., [

19,

33]). However, measurement replication is determined by the minimum accuracy required by regulators, and is not standard practice in the water sector, particularly with respect to chlorine measurements. Most chlorine studies in the water field are based on single measurements (e.g., [

34]), and only a few microbiological studies mention replicate measurements in general (e.g., [

19,

35]) and triplicate measurements in particular (e.g., [

36,

37,

38]). This context highlights that chlorine measurement strategies are varied and associated with different measurement errors. These errors propagate when computing the associated bulk decay coefficient.

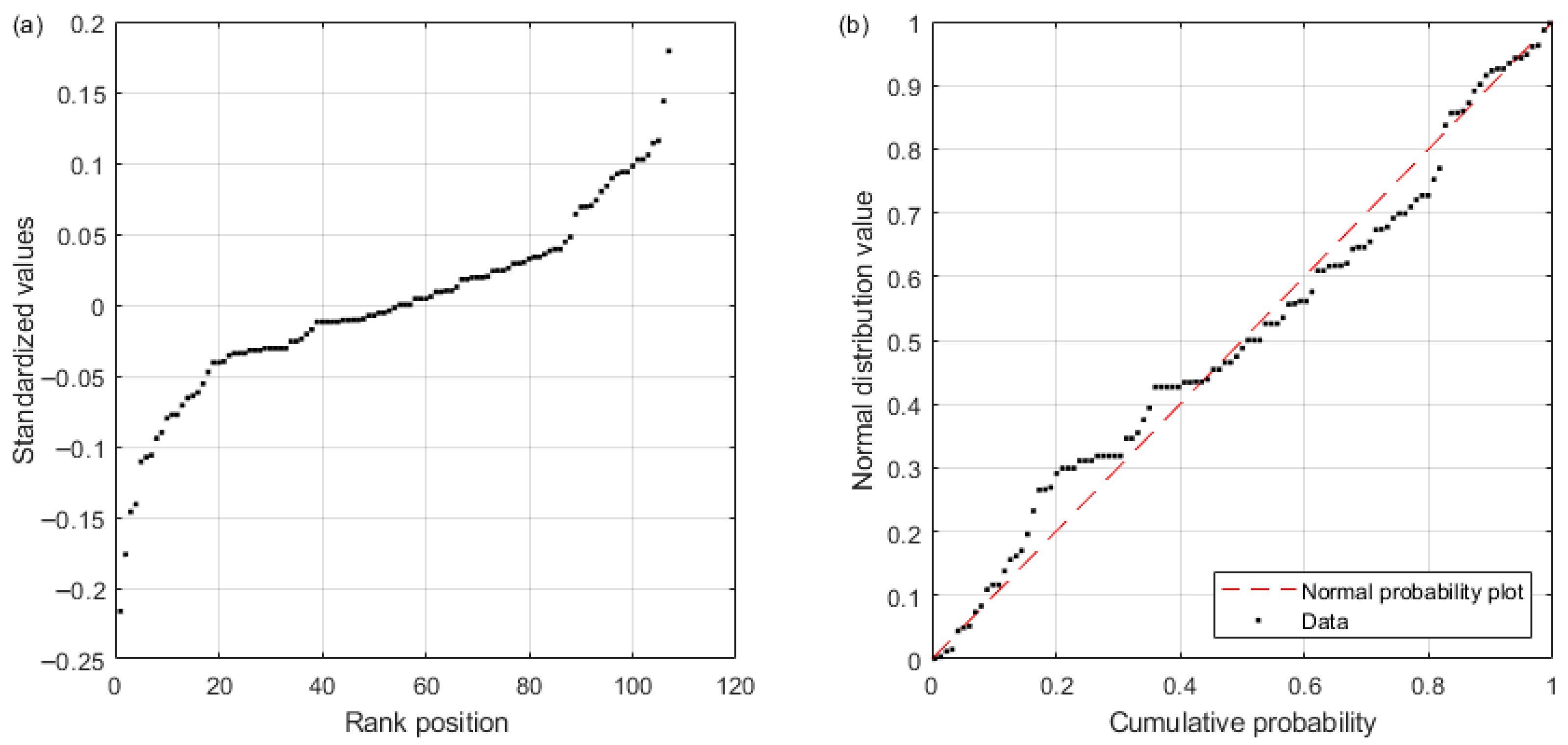

Figure 1 provides a conceptual representation of a chlorine bulk decay process, which is usually characterized through standard bottle tests (e.g., [

15]). Standard bottle tests rely on individual measurements at each of the observed times, which are then used to adjust

(best fit to data). This approach provides a single value of

and does not enable us to account for the impact of chlorine measurements on the bulk decay coefficient.

Figure 1a shows that if more than one measurement was taken at each time, there would be several possible curves (i.e., combinations of measurements) that could be fitted to chlorine measurements, i.e., there is a range of possible

values. This means that, because chlorine measurements are not accurate enough, the bulk decay coefficient should be represented by a distribution function rather than a single value (

Figure 1b). To overcome this issue, this work will develop a methodology to statistically characterize the bulk decay coefficient (mean and standard deviation) and will demonstrate with real values (see Results section and related appendices) that the variability of

is not negligible and should be considered when comparing bulk decay coefficients. This approach could be key to assessing the impact of chlorine measurement and model errors on

and so to understand chlorine dynamics in water supply systems.

Therefore, the aim of this paper is to develop a methodology that statistically fits chlorine’s bulk decay coefficient (mean value and standard deviation) at water supply systems, tracking uncertainty along the process. Following common practice in the field, the method relies on bottle test data, which in this case are fitted to a first-order bulk decay model; however, it could similarly be adapted to alternative models. The mean value of

is here computed using state estimation techniques, which apply a non-linear mathematical algorithm to identify the most likely state of a variable (in this case,

) while considering (bottle test) measurement errors and system knowledge (in this case, the assumed bulk decay model). The associated standard deviation is computed by propagating measurement errors to the

solution. This approach provides a solid framework to statistically characterize

. It goes one step further with respect to previous studies, which only provide one possible

value (e.g., [

18,

20]). Systematic statistical fitting of

(mean value and standard deviation) gives insight into the variability of the bulk decay coefficient, which could be crucial when analyzing changes over time and/or with temperature. Therefore, this work introduces a methodology to understand, monitor, and model chlorine decay processes under varying conditions, including those driven by climate change [

39,

40]. We want to highlight that this methodology constitutes a first scientific contribution intended to identify (and quantify) a problem that affects both industrial practice and research. The methodology has potential to evolve into a tool that can be operationally used by water utilities (knowledge transfer to industry) once chlorine decay processes are better understood on a scientific level (see Discussion section).

3. Results

The methodology described in

Section 2 is applied in this work to characterize the bulk decay coefficient of three different water sources (A, B, and C). Water grab samples are taken immediately before chlorination at three treatment works in the region of Castilla-La Mancha (Spain). In order to assess the repeatability of the process and to highlight the physical meaning of state estimation/uncertainty assessment results, each bottle test is carried out three times (in parallel) in the exact same way for the water sample from each source. Replicated bottle tests will be denoted as “X-E01”, “X-E02”, and “X-E03”, with “X” being “A”, “B”, or “C” depending on the water source. This means that each grab sample presents a volume of approximately 12 L, and the laboratory process described in

Section 2.1 is carried out in three parallel isothermal baths (i.e., chlorination happens at three different 3.8 L Winchester bottles) for each water source. Time blocks are slightly displaced among the 3 tests to ensure that the same person can carry out the triplicate lab test in parallel. Only one bottle test is needed to compute the uncertainty of the bulk decay coefficient with the methodology presented in this paper, but replication is carried out for these three samples to validate the method and to illustrate its relevance.

Table 2 summarizes the main characteristics of the grab samples from each of the three sources/treatment works when processed at the laboratory before starting the bottle test. TOC is measured only once for the total volume of water (12 L), but temperature, pH and ICC are measured for each parallel bottle test (3.8 L) following the procedure described in

Section 2.1.

Table 2 shows that TOC is higher for treatment works A compared to B and C. Treatment works A receives the water from a reservoir (surface water), whereas treatment works B and C run on groundwater. Grab samples are taken in all three cases after water has gone through all treatment stages (except chlorination), so it can be assumed that source A is richer in organic matter than sources B and C (there was virtually no organic matter at source C when the sample was taken). The higher TOC for source A justifies the lower ICC values compared to sources B and C (chlorine reacts faster due to the greater presence of organic matter, lowering the ICC). pH values are slightly higher for treatment works A (7.0–7.2) and C (7.4–7.5) compared to B (6.0–6.3), but remain below 8, which is the maximum recommended pH for drinking water [

59].

Table 3 gathers free chlorine measurements (with replications) over time for the three parallel bottle tests carried out with grab samples from sources A, B and C. Measurements for the first average time are represented in gray font and will be disregarded for the

analysis as explained in

Section 2.1. It should be noted that the number of average times (

) varies depending on the rate at which chlorine decays (4 effective times for A, 6 effective times for B and C). Chlorine decays faster for sample A due to its higher TOC. Measurements included in

Table 3 are analyzed in the next subsections for samples A, B, and C (respectively) according to the procedure described in the methodology.

3.1. Treatment Works A

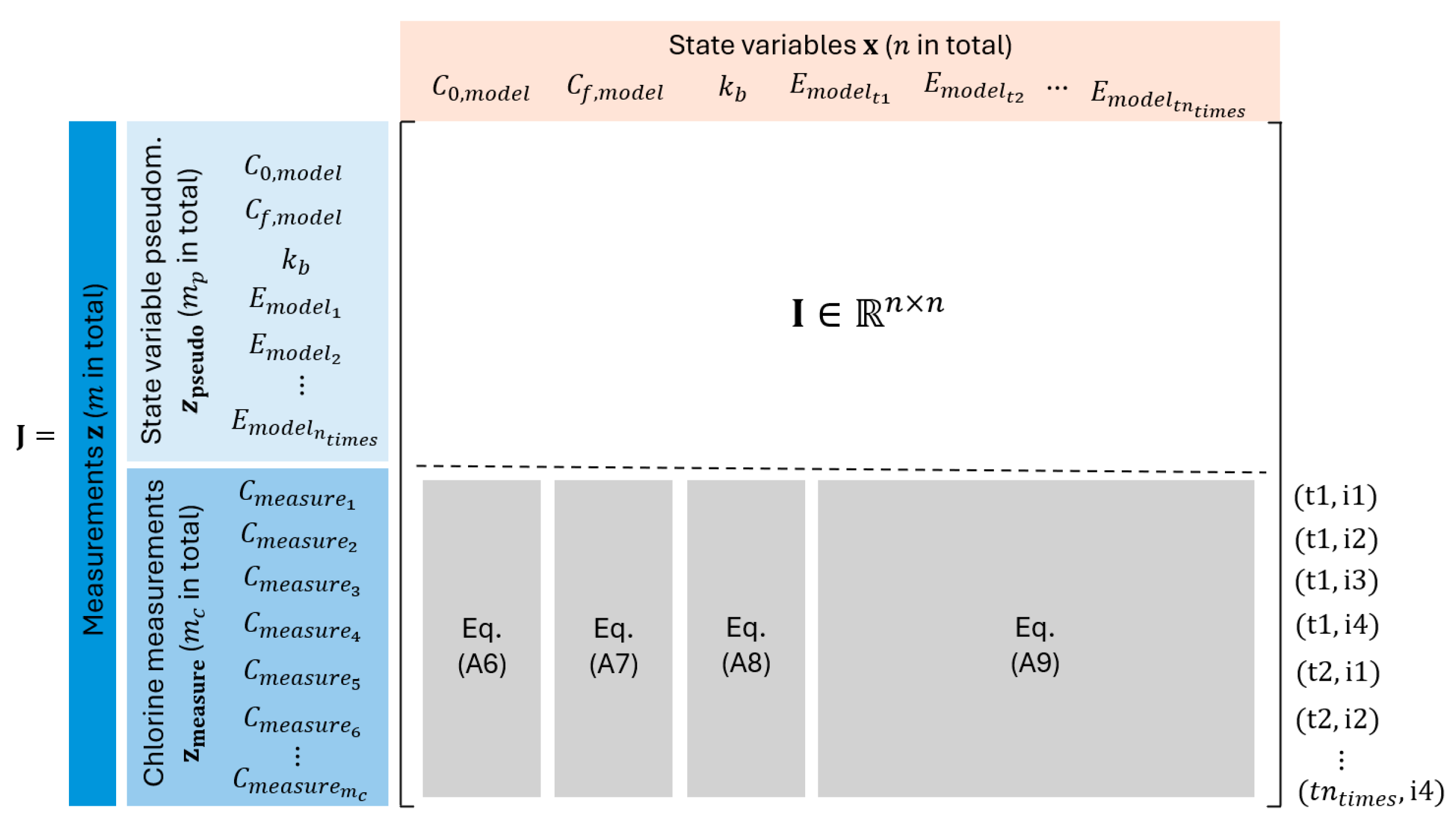

State estimation (

Section 2.3), uncertainty quantification (

Section 2.4), and outlier detection (

Section 2.5) formulations are applied in this subsection to bottle test chlorine measurements for treatment works A (surface water).

Figure 3 gathers the results for the first replication of the bottle test (A-E01).

Figure 3a provides a representation of bottle test chlorine measurements and the adjusted first-order bulk decay model (with confidence intervals). This figure shows that there are four sets of chlorine measurements for each of the four average times included in

Table 3 (disregarding the first hour values in gray). As expected, the confidence interval

(Equation (15)) is wider than

(Equation (14)). For A-E01, all chlorine measurements lie within the expanded confidence interval

. The estimated chlorine concentrations are approximately in the middle of the range of chlorine measurements at different times and reach 0 mg/L in less than 2 days.

Figure 3a also includes the mean (0.0638 1/h), standard deviation (0.0088 1/h), and coefficient of variation (13.84%) of the bulk decay coefficient. The mean value lies within the range of bulk decay coefficients summarized by [

20]. The coefficient of variation, 13.84% shows that there is a non-negligible uncertainty associated with the bulk decay coefficient.

Figure 3b shows the standardized errors of pseudomeasurements (i.e., state variables) as provided by Equation (12). The threshold value for outlier detection in this case (99%

) is clearly greater than error values, which are low for the first three state variables (

,

and

) and the remaining

state variables (4 because 4 average times are being considered). This is reasonable given that pseudomeasurements are a priori estimations of expected state variable values.

Figure 3c presents the measurement (free chlorine) standardized errors as provided by Equation (12) as well. The threshold value for outlier detection is higher than the corresponding errors, so no outliers are detected.

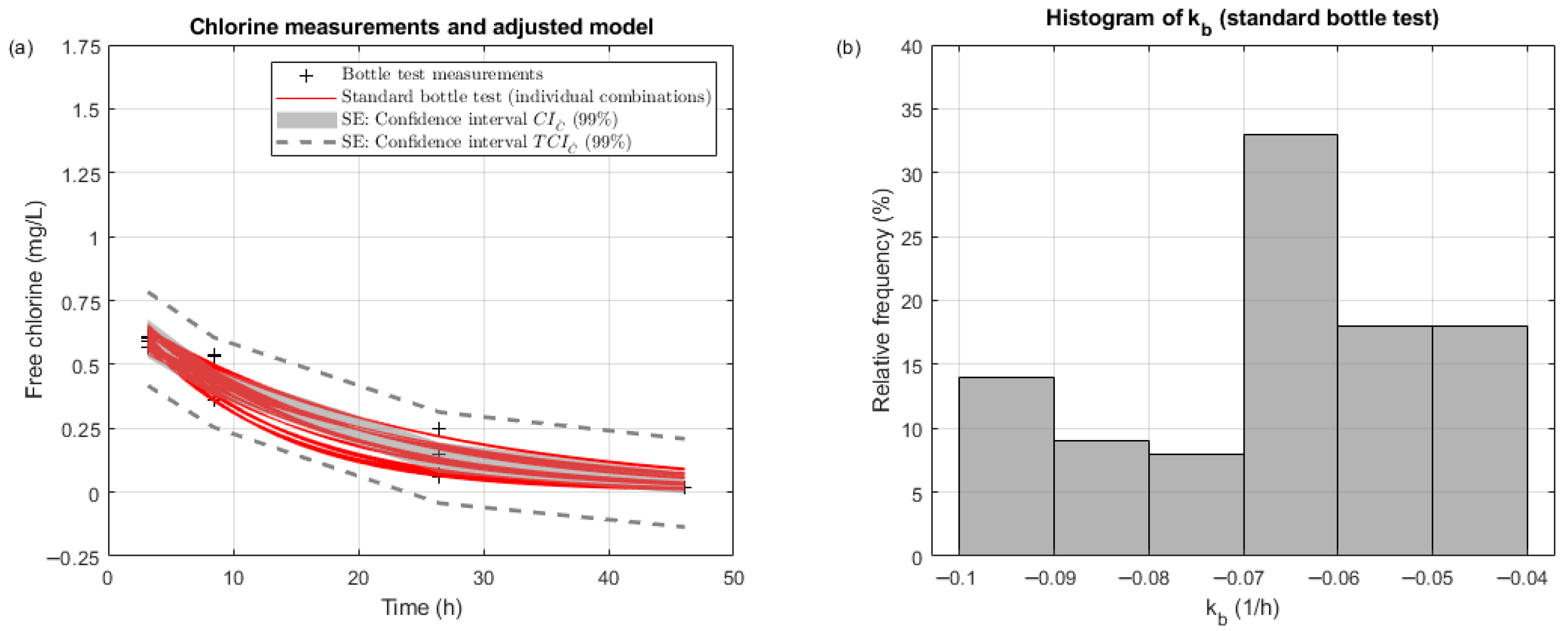

State estimation confidence intervals may be compared with standard bottle test results. As explained in the Introduction, standard bottle tests rely on taking one measurement at a time and conveniently adjusting the assumed model (in this case, an exponential fit for a first-order bulk decay model).

Figure 4a shows that each combination of measurement replications leads to different fitted lines (in red) and

values. There are 400 combinations for the 18 measurements taken in A-E01 (4 times with 4 or 5 replications). All fitted lines from these combinations (in red) fall within the

(Equation (15)).

Figure 4b gathers the relative histogram of the bulk decay coefficients obtained from these combinations. This histogram is consistent with state estimation results (mean 0.0638 1/h, standard deviation 0.0088 1/h). Overall,

Figure 4 (which is consistent with conceptual

Figure 1) proves that chlorine measurement errors have an impact on the estimated bulk decay coefficient. State estimation presents added value with respect to the traditional approach because it consistently propagates uncertainty. The state estimation formulation characterizes the distribution of fitting curves affected by the uncertainty of the fitting data. Therefore, it is the most effective way to evaluate the fitting data uncertainty effect.

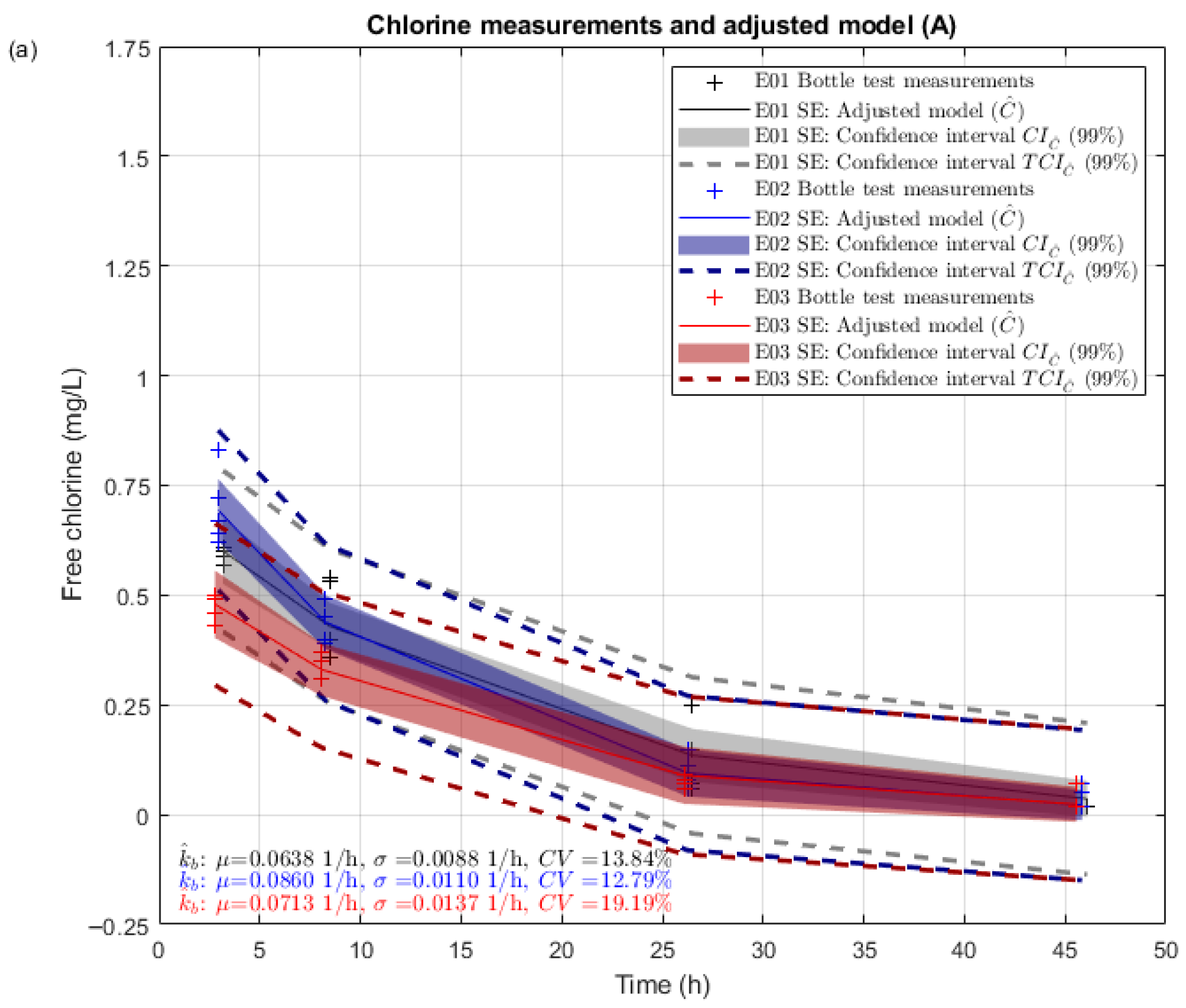

Table 4 gathers basic statistical properties for all state variables and bottle tests from source A. The mean and standard deviation are included for all state variables, but the coefficient of variation (CV) is only included for those state variables whose mean value is expected to be different from zero (initial chlorine concentration and bulk decay coefficient according to

Table 1).

Table 4 shows that the mean initial chlorine concentration for the model varies between 0.59 and 0.89 mg/L depending on the bottle test. Its standard deviation varies between 0.05 and 0.06 mg/L, a range that is considerably lower than the standard deviation assumed for the corresponding pseudomeasurement (0.50 mg/L, see

Table 1). This occurs because chlorine measurements (and the assumed model) help reduce the standard deviation of the pseudomeasured initial chlorine concentration (and the rest of the state variables) through the state estimation process. The mean of the final concentration (according to the model) and model errors tend to be zero, with a standard deviation consistent with the assumed 0.01 mg/L value (

Table 1). The mean bulk decay coefficient adjusted for these replicate tests varies between 0.0638 and 0.0860 1/h. Its standard deviation is roughly 0.01 1/h, a value once again considerably lower than the standard deviation assumed a priori for the corresponding pseudomeasurement (0.50 1/h, see

Table 1). Assuming a 99% level of confidence (

), the range of values for

would be 0.0411–0.0865 1/h (A-E01), 0.0576–0.1144 1/h (A-E02), and 0.0360–0.1066 1/h (A-E03). The fact that there is some degree of overlap between the three replications (0.0576–0.0865 1/h) validates the state estimation approach presented here. The empirical coefficient of variation computed considering the three

values adjusted with SE is 15.32%. This value is consistent with the CV values obtained for

from SE (12.79–19.19%, average 15.27%). No outliers have been identified according to Equations (12)–(15) for these bottle tests.

3.2. Treatment Works B

SE results for bottle tests B are now presented.

Figure 5a gathers state estimation results for the first bottle test (B-E01).

Figure 5a is comparable to

Figure 3a for test A-E01. In general, the adjusted model does not fit well to the range of chlorine measurements at each time, and this is especially visible at the third, fifth, and sixth effective times (there is one outlier at the third average time).

Appendix B shows that pseudomeasurement errors (

Figure A3a) keep within the CI range, but measurement 9 is an outlier (

Figure A3b,

Table 3). As already explained in

Section 2.5, this chlorine measurement should be removed, and SE should be re-run. It is also interesting to highlight that chlorine measurements after almost 250 h are still clearly different from zero in

Figure 5a. As mentioned in

Section 2.2, tests longer than 250–300 h are out of practical interest because water age values over 10 days are unlikely in most pipes within a water distribution system, and this work intends to adjust a model useful to support network operation. Chlorine concentrations do not reach 0 mg/L for B-E01 (values between 0.25 and 0.44 mg/L at the last average time according to

Table 3), B-E02 (0.48–0.62 mg/L), nor B-E03 (0.30–0.55 mg/L). These values pinpoint that it may be worth reconsidering the assumed statistical properties for the final chlorine concentration of the model. By default, we recommend assuming a mean value of 0 mg/L and a standard deviation of 0.01 mg/L for

(

Table 1), but it does not seem to be the best assumption for samples from source B.

Figure 5b shows the updated version of

Figure 5a once chlorine measurement 9 (outlier) has been disregarded, and the standard deviation assumed for the final concentration of chlorine

has been increased to 0.50 mg/L. This standard deviation shows a lack of confidence in the assumed final concentration (like for

and

) and should allow the final chlorine concentration to differ from zero.

Figure 5b (together with

Figure A4a,b, see

Appendix B) shows that there are no outliers after these changes are implemented, and there is a better fit for chlorine measurements overall. Removing the outlier does not have a significant effect on the estimated

, but increasing the standard deviation of

significantly affects the mean bulk decay coefficient, which increases from 0.0046 1/h (

Figure 5a) to 0.0133 1/h (

Figure 5b). This change in assumption also implies a significant increase in the bulk decay coefficient standard deviation (from 0.0004 to 0.0026 1/h) and CV (from 9.30 to 19.80%). However, it is the most realistic approach given that chlorine concentrations during the bottle test do not reach 0 mg/L.

Table 5 gathers the basic statistical properties for all state variables in bottle tests B. All results have been computed with the increased standard deviation for the final chlorine concentration pseudomeasurement (

). Apart from the outlier removed for B-E01 (previously explained), one outlier is removed for B-E02 (measurement 21) and B-E03 (measurement 22), as highlighted in

Table 3.

Table 5 shows that the initial chlorine concentration for the model varies between 0.94 and 1.01 mg/L depending on the bottle test replication. Its standard deviation has reduced with respect to the pseudomeasurement assumption (0.50 mg/L, see

Table 1), as happened for sample A. The mean of the final concentration (according to the model) varies between 0.32 and 0.52 mg/L. Its standard deviation varies between 0.04 and 0.06 mg/L. This range is considerably lower than the standard deviation now assumed for

(0.50 mg/L) but greater than the initially assumed 0.01 mg/L (see

Table 1). The mean bulk decay coefficient adjusted for these replicate tests varies between 0.0107 and 0.0168 1/h. Its deviation ranges 0.0025–0.0038 1/h, narrowing down the uncertainty initially assumed for this pseudomeasurement (0.50 1/h). Like for source A, there is an overlap in the confidence intervals for

. The empirical coefficient of variation computed considering the three bulk decay coefficient values adjusted with SE is 22.51%. This value is greater than that obtained from A grab sample (15.32%), but it is still consistent with the CV values that are being obtained from SE for

(19.80–23.70%, average 22.12%).

3.3. Treatment Works C

Figure 6a shows state estimation results for the first bottle test (C-E01). There are no outliers in this bottle test. However, the assumption of the final chlorine concentration reaching zero is dubious again (concentrations 0.55–0.70 mg/L after almost 300 h according to

Table 3).

Figure 6b shows the corresponding plot after increasing the assumed standard deviation for the final concentration of chlorine

to 0.50 mg/L (as already performed for treatment works B). Releasing the asymptote condition leads to a more defined curvature and provides a better fit for the data. The

coefficient increases (from 0.0019 1/h to 0.0054 1/h) but is still low in absolute terms. It is lower than the coefficients for treatment works A and B, and on the lower end of values in [

20]. The increased standard deviation for the final chlorine concentration translates into a greater CV for

(from 10.35% to 46.68%). This might suggest that different average times should be studied when analyzing bulk decay coefficients of water samples with low TOC to better capture the curvature and asymptote of the curve.

Table 6 provides a summary of SE results for bottle tests C, considering an increased standard deviation of 0.5 mg/L for the final chlorine concentration in all cases. Only one outlier has been removed for test C-E03 (measurement 13, see

Table 3).

Table 6 shows that the estimated mean final chlorine concentration is clearly above zero for C-E01 (0.49 mg/L) and C-E03 (0.60 mg/L) but remains close to zero for C-E02 (−0.03 mg/L). This happens because chlorine measurements present an almost linear behavior for the average times that have been analyzed in the bottle test. This means that the

value is very low (the exponent of the exponential model tends to zero), and there is no clear asymptote for the final chlorine concentration. This is reinforced by the variation in estimated bulk decay coefficients across the three tests (from 0.0014 1/h to 0.0104 1/h). These results suggest that the low content of organic matter for treatment works C (i.e., negligible TOC) leads to more random results in terms of the bulk decay coefficient. This phenomenon can be attributed to the increased randomness of the inherently unstable chlorine reaction, which could be further exacerbated by the uneven distribution of organic matter across subsamples. Note that the CV obtained for estimated

results (36.40–60.84%, average 47.97%) is lower than the coefficient of variation obtained when considering the three mean

values adjusted with SE (78.65%). This means that three replications of the bottle test are not enough, i.e., there is some additional uncertainty due to the low representativeness of the samples.

4. Discussion

Results from

Section 3 show that the bulk decay coefficient varies with the water source. The average bulk decay coefficient considering triplicate bottle tests is 0.0737 1/h (source A, surface water), 0.0136 1/h (source B, groundwater), and 0.0057 1/h (source C, groundwater) for the three-treatment works, respectively. These results reinforce the idea that

increases with TOC (e.g., [

15,

18]). In this case, high TOC values correspond to surface water (A), but additional tests should be carried out at different locations to validate that this is always the case. For high

values (A), the curvature of the exponential function is better defined, and chlorine values steadily approximate 0 mg/L without any outliers. This happens because chlorine measurements clearly decrease from time to time during the bottle test. However, for low

values (B and C), the curvature is less defined, and chlorine values may not even reach 0 mg/L within a reasonable bottle test duration (<250–300 h). Since measurement values do not change clearly over time, the methodology depicted in

Figure 2 (which includes measurement replication, state estimation, uncertainty quantification, outlier detection, and revision of pseudomeasurement assumptions) is essential for processing bottle test data from this type of water source. We must acknowledge that, based on the results, it seems that very low TOC values seem to be associated with very low bulk coefficients (as in treatment works C). This implies that chlorine will decay slowly through the network, and so the risk of falling below the recommended 0.2 mg/L free chlorine threshold will be low. The proposed methodology enables the identification of this type of water source by systematically computing the uncertainty of the bulk decay coefficient.

It should be noted that estimated bulk decay coefficients are associated with a non-negligible standard deviation (and CV). The average CV (according to

SE results) considering triplicate bottle tests are 15.27%, 22.12% and 47.97% for sources A (surface water) and B/C (groundwater), respectively. The CV of grab sample B is higher than A mainly because of the need to increase the assumed standard deviation for the final concentration of the model, a decision that comes determined by chlorine measurements evolution over the bottle test, which do not tend to zero in the time window considered. The CV of grab sample C is even greater due to the low repeatability of bottle tests in water samples with low content of organic matter.

Figure 7 summarizes bottle test chlorine measurements, adjusted first-order bulk decay models, and associated confidence intervals for grab samples A (

Figure 7a), B (

Figure 7b), and C (

Figure 7c).

Figure 7a presents a greater dispersion at the beginning of the bottle test due to the assumed high standard deviation for ICC (see

Table 1).

Figure 7b presents a greater dispersion at the end of the bottle test because of the increased standard deviation for

.

Figure 7c presents a greater dispersion in between due to the additional sampling uncertainty. There is some degree of overlap in all of them.

High standard deviations for

happen because, as proved by the triplicate bottle tests, the chemical reaction of chlorine does not always happen in the exact same way. This is especially noticeable when there is a low content of organic matter.

Figure 7 highlights these differences by representing results for each replicate bottle test in different colors (black for E01, blue for E02, red for E03). Chlorine decays over time in different ways due to factors that are not included in the assumed model, which is not perfect. Also, sodium hypochlorite is known to experience instabilities (e.g., [

41,

42]), and this adds complexity to the chemical reaction. This work has proved that deviations are intrinsic to chlorine decay processes when they happen in bottles in a laboratory (controlled environment). Additional factors interact in service reservoirs or network tanks (e.g., irregular agitation, poorly preserved reactive agents, etc.). This does not mean that bottle tests should be systematically replicated in practice to estimate the associated dispersion, but it underscores that specific procedures (like state estimation and uncertainty assessment) should be implemented to process the results of a single bottle test. In this work, we have repeated each experiment three times to validate that the resulting

distributions overlap, and so the methodology is consistent to identify the potential range of

. Our recommendation is to carry out only one bottle test with several replicate chlorine measurements at each time, and then quantify the uncertainty of

with an appropriate statistical fitting process, as conceptually illustrated in

Figure 1.

The most interesting aspect of the presented methodology is that the state estimation approach tracks the uncertainty of all involved variables regardless of the model adopted or the measurements available. This is crucial because results show that the uncertainty of the bulk decay coefficient is non-negligible, even with measurement replications, which reduce measurement error effects. The uncertainty of the bulk decay coefficient depends on the number of replications. The method presented in this work can be applied to compute the most likely value of

with less data, without replications, or with fewer measurements over time, quantifying the impact of each of these scenarios in terms of uncertainty. Applying a standard statistical fit process to bottle test data without quantifying the associated uncertainty (traditional bottle test approach) may lead to bulk decay coefficients that are apparently inconsistent. The fact that a consistent procedure to compute the bulk decay coefficient has not been applied before could partly explain the wide range of bulk decay coefficient values registered for different water sources and/or temperatures in the past [

18,

20]. The CVs above 15% obtained here underscore that uncertainty is noticeable and should be considered when analyzing temporal shifts in

, for example, due to potential mixtures of water sources, seasonal variability, temperature changes, etc. Disregarding this uncertainty may lead to false conclusions. It should also be considered when evaluating chlorine decay at the wall, which is typically computed as the difference between the total decay and the modeled bulk decay [

17,

23]. This could, in turn, be useful to better understand biofilm formation and detachment processes [

37,

40]. The methodology presented here is developed to explain part of the observed behavior and is aligned with the general effort that is currently being made to systematically process and understand water quality data/dynamics in water distribution systems (e.g., [

6,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64]). At this stage, the proposed approach should be regarded as a methodology rather than a practical tool, requiring expert analysis and interpretation of results (research domain). More research is needed before establishing practical recommendations for implementation. For example, the methodology should be applied to a wider range of water compositions (beyond A, B, and C) and different chlorine measurement technologies/procedures (other than KEMIO and the proposed bottle test with replications). Moreover, all uncertainty sources should be mapped and their impacts assessed. In any case, this framework—combining state estimation and uncertainty assessment—has the potential to evolve into an operational tool for water utilities (knowledge transfer to industry) once the chlorine decay process is better understood.

5. Conclusions

This work highlights the importance of measurement uncertainty when computing the bulk chlorine decay coefficient . Moreover, it provides a methodology to statistically fit the bulk chlorine decay coefficient (mean and standard deviation) from the bottle test results. The process starts by carrying out bottle tests (standard practice in the field) with replicate measurements. Then, state estimation is used to compute the mean value of the bulk decay coefficient by combining bottle test free chlorine measurements, a decay model (in this case, first-order bulk decay), and some a priori estimations or pseudomeasurements. The uncertainty (i.e., standard deviation) of all variables is then quantified by implementing the FOSM method, which enables computation of confidence intervals that can be used to identify measurement outliers and/or incorrect assumptions.

The method is applied to statistically fit the bulk decay coefficient at three treatment works (A, B, and C). Results (for triplicate bottle tests) validate the method and show that presents non-negligible uncertainty in some cases (>15%). The uncertainty of the bulk decay coefficient increases in this work for groundwater grab samples, which are associated with a lower content of organic matter. Computed standard deviations could further increase depending on the sampling strategy, measurement principle, etc. The state estimation approach presented in this work is designed to cope with a wide range of scenarios, assumptions, and/or models, so it provides a systematic methodology to effectively analyze and compare (considering uncertainty) bulk decay coefficients from different sources, at different moments, with different temperatures, etc. This approach may play a crucial role in explaining the variability of the bulk decay coefficient reported in previous works and could be essential to understand, monitor, and/or model chlorine decay at water supply systems.