1. Introduction

Sea level change is a critical indicator of climate variability and oceanographic dynamics, particularly in marginal seas and coastal regions where anthropogenic and natural influences converge [

1,

2,

3]. In the Northwest Pacific, the East Sea (Sea of Japan) and its surrounding areas, including Dokdo (Dok Island), Ulleungdo, and the southeastern coast of the Korean Peninsula, exhibit complex sea level variability influenced by monsoon forcing, typhoons, and large-scale circulation systems such as the Kuroshio Extension and the Tsushima Warm Current [

4,

5]. Monitoring and understanding sea level variability in this region is essential for coastal hazard assessment, maritime safety, and climate change adaptation strategies [

6,

7].

However, continuous long-term sea level observations in the open ocean near Dokdo are lacking due to the absence of long-term in situ tide gauges [

8,

9]. In contrast, the Permanent Service for Mean Sea Level (PSMSL) provides a network of tide gauge stations around the East Sea and the broader region, offering a valuable opportunity to estimate sea level at data-sparse locations through statistical interpolation and machine learning (ML) techniques [

10,

11]. Recent advances in ML enable the reconstruction of missing or unavailable observations by leveraging spatial and temporal patterns from nearby stations [

12,

13,

14].

In this study, we aim to reconstruct and analyze monthly sea level timeseries at Dokdo from 1993 to 2023 using a combination of geospatial interpolation, statistical models, and ML algorithms [

15,

16]. We begin by collecting and preprocessing monthly mean sea level data from the 13 selected PSMSL stations closest to Dokdo, applying outlier filtering and distance-based reordering. Two baseline methods, simple ensemble averaging and inverse distance weighting (IDW), are employed to generate initial predictions at Dokdo [

17,

18]. These are compared to results from a suite of ML imputation models applied to the 13 stations, including tree-based ensembles (Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM), regularized regression (Ridge, Bayesian Ridge), proximity-based methods (KNN), and neural networks [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Large-scale climate modes modulate sea level in the East Sea (Sea of Japan), introducing variability on interannual to multi-decadal timescales. The El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), and Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) influence regional sea level through steric height changes, wind forcing, and basin-scale circulation, and can temporarily accelerate or decelerate the background rise [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Our 1993–2023 reconstruction overlaps major events such as the 1997–1998 El Niño and early-2000s PDO phase shifts, but the limited time span precludes a full resolution of longer climate cycles [

37,

38,

39]. In this study, we focus on developing and validating a reproducible reconstruction framework for Dokdo during the satellite-altimetry era, while acknowledging that these climate modes provide essential context for interpreting regional sea-level change [

30,

32].

Our approach allows for the assessment of interannual to decadal sea level variability at Dokdo in the absence of direct long-term tide gauge measurements [

40]. By integrating geodesic distance, regional coherence, and advanced imputation techniques, we provide a robust and reproducible methodology for reconstructing historical sea level at isolated marine locations [

41]. The reconstructed records offer insights into regional oceanographic trends and provide a foundation for future studies on sea level rise and variability in the East Sea and surrounding maritime zones [

42,

43].

2. Data and Methods

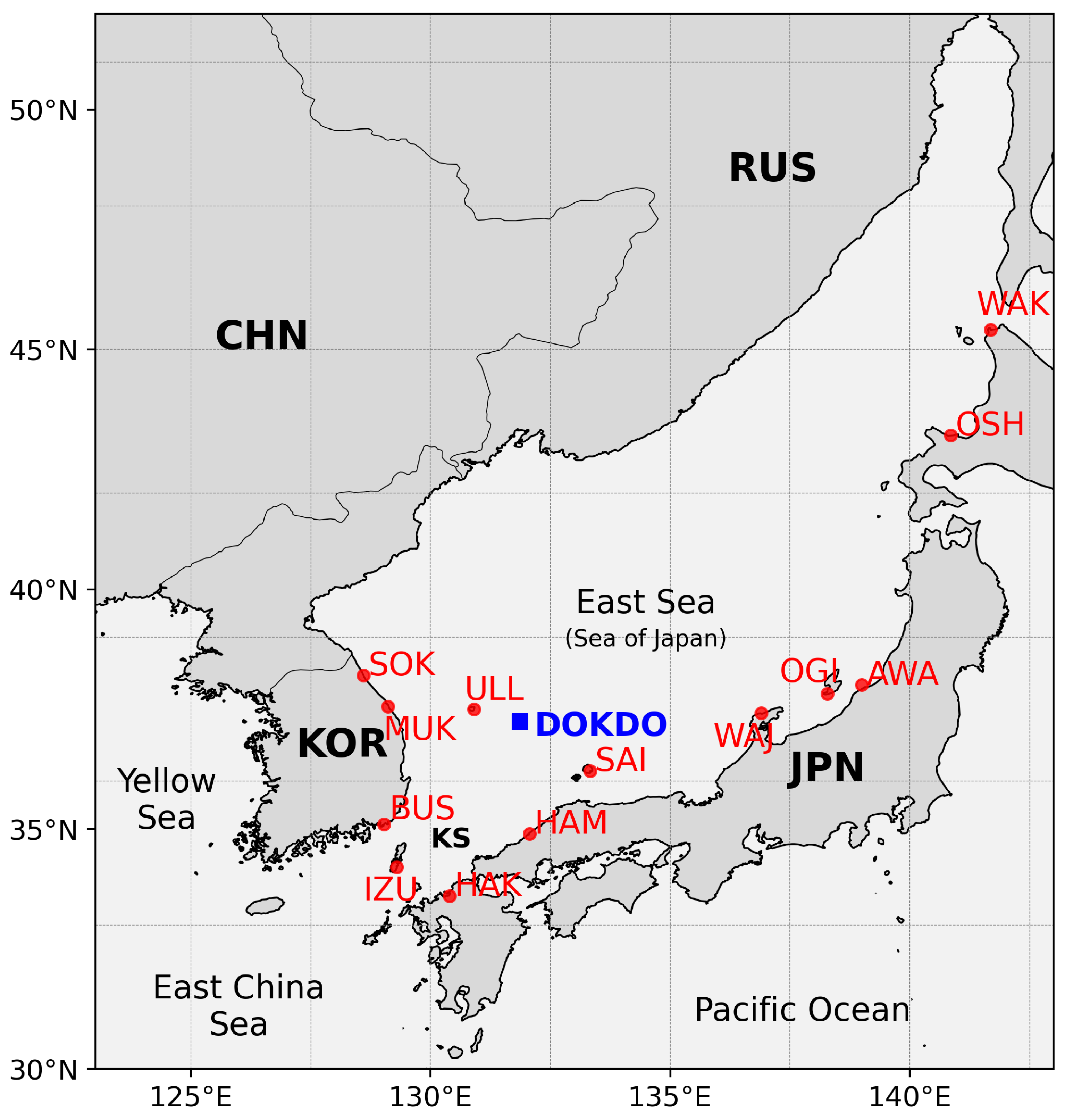

This study investigates monthly sea level variability at Dokdo from 1993 to 2023 by utilizing observations from 13 selected nearby PSMSL tide gauge stations distributed across the East Sea and adjacent Northwest Pacific coastal regions (

Figure 1). These stations, located within approximately 1000 km of Dokdo, form a spatially coherent observational network that captures regional oceanographic variability. Original PSMSL records were compiled for each station (

Figure 2) and processed through a ±3σ outlier filtering procedure to remove anomalous values. Tide-gauge records were corrected for the inverse barometer (IB) effect, which represents the dominant component of the Dynamic Atmospheric Correction (DAC) and ensures consistency with satellite altimetry products. Vertical land motion (VLM) corrections were not applied in this study, as Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS)-constrained rates are not uniformly available for all stations in the East Sea region. Instead, we focus on reconstructing relative sea level, and we discuss the implications of VLM for tide-gauge/altimetry consistency in

Section 3.4. Tide-gauge observations were obtained from the PSMSL [

44], while satellite altimetry products were taken from the Copernicus Marine Service (CMS; [

45]).

All records were aligned to a common monthly time axis to enable consistent interstation comparison and reconstruction of missing data. To evaluate the completeness of the tide gauge records, we quantified the number and distribution of missing months for each station over 1993–2023 (

Table 1). Most stations were highly complete, with <5% missing data (e.g., Saigo, Hamada II, Wakkanai), while a few exhibited longer gaps more than 19 months (e.g., Izuhara II, Hakata, Awa Sima). The presence of both short sporadic gaps and longer discontinuities motivated the use of ensemble-based machine learning imputation methods, which are more robust than single-model or linear interpolation approaches. By explicitly accounting for heterogeneous gap structures across stations, the framework ensures that reconstructions retain physical consistency and minimize biases from uneven data coverage.

To independently validate the reconstructed sea-level time series at Dokdo, we used satellite altimetry data from the CMS. Specifically, we obtained the monthly gridded sea-level anomaly product [

46], which provides global anomalies on a 0.25° latitude–longitude grid from January 1993 onward. The dataset is publicly available through the CMS portal [

46]. To extract the altimetric sea-level anomalies near Dokdo, we identified the grid cell geographically closest to the Dokdo coordinates (37.241° N, 131.865° E) by minimizing absolute latitude and longitude differences. Because CMS provides relative anomalies, whereas tide-gauge composites carry absolute levels, we applied a mean-alignment procedure: The temporal mean of the extracted SLA series was removed, and the mean of the 13-station PSMSL ensemble (monthly, gap-filled) was computed. This scalar mean was added to the SLA series, producing a level-aligned product comparable with tide-gauge data. The aligned series represents CMS at Dokdo adjusted to the PSMSL reference level. Because tide-gauge and satellite altimetry observations reflect different spatial scales—tide gauges capture nearshore processes such as coastal setup, local winds, and waves, whereas altimetry averages offshore conditions over larger areas—systematic offsets are expected. To reconcile these differences, we applied a linear ordinary least squares (OLS) regression between the CMS SLA and the tide-gauge reconstruction for their overlapping period. This adjustment removes systematic biases and scales the altimetric anomalies to the tide-gauge reference frame. We also constructed 95% prediction intervals around the adjusted altimetry series to quantify mapping uncertainty.

Validation skill was assessed using multiple metrics, root-mean-square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), correlation coefficient (r), and coefficient of determination (R2), together with moving-block bootstrap confidence intervals (12-month blocks, 1000 replicates). Metrics were computed for the full overlapping record (1993–2023) and for targeted extreme-event windows, including the 1997–1998 El Niño and the 2003 typhoon season. This procedure ensured that the Dokdo tide-gauge reconstruction was validated against an independent large-scale dataset while properly accounting for local-to-regional observational differences.

To reconstruct missing values in the monthly tide-gauge records, we applied an Iterative Imputer framework with eight different regression algorithms: K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN; [

47]), Random Forest (RF; [

48]), Extra Trees (ET; [

49]), Bayesian Ridge (BR; [

50]), Ridge Regression ([

51]), Multilayer Perceptron (MLP; [

52]), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost; [

53]), and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM; [

54]). Each model was trained to iteratively predict missing entries from the available station network. To ensure comparability and avoid overfitting to any single method, all regressors were implemented with standardized, lightly tuned hyperparameters. For example, RF and ET were limited to 100 trees each, XGBoost and LightGBM to 100 boosting rounds, and the MLP to 1000 training iterations. KNN used three nearest neighbors, while Ridge and Bayesian Ridge followed their default regularization schemes. These choices balanced computational cost and predictive stability, while ensuring that no individual algorithm dominated due to excessive tuning. The ensemble mean across the eight imputed datasets was then used as the final filled product, which stabilizes the time series by reducing model-specific biases and noise.

Table 2 summarizes the eight regression models embedded in the Iterative Imputer. Their complementary assumptions ensure that the ensemble average mitigates model-specific biases and enhances reconstruction robustness.

To ensure robustness, we clarify that the eight imputation methods were implemented to construct an ensemble, with a standardized set of hyperparameters applied across all models (

Table 2). This approach emphasizes methodological diversity rather than fine-tuned optimization of individual algorithms. Each method contributes distinct strengths: tree-based approaches capture nonlinear dependencies, linear regressors provide interpretable baselines, and neural networks offer flexible mapping of complex relationships. Because no single method performed optimally across all stations and time periods, we combined their outputs into an ensemble mean. This averaging reduces model-specific biases while preserving the dominant physical and statistical signals, resulting in reconstructions that are both stable and transferable to other coastal regions with sparse tide-gauge coverage.

The resulting reconstructed timeseries for each model are shown in

Figure 3. An ensemble mean across the eight ML outputs was computed to generate a robust, gap-filled dataset (

Figure 4). This ensemble averaging helped minimize overfitting and model-specific noise, yielding a stable representation of sea level variability across the region. Using this ensemble dataset, monthly sea level at Dokdo was estimated using a spatial interpolation approaches: IDW, where geodesic distances from Dokdo to each station were used to assign weights (

Figure 5 and Equation (1)). To reconstruct sea level

at location

(e.g., Dokdo) from surrounding stations:

where

,

, and

are sea level at stations

, distance from station

to location

, number of nearby stations used (e.g., 13). Stations in closer proximity to Dokdo, such as Ulleung, Mukho, and Saigo, received greater influence in the IDW-based estimation. This dual-method approach provided two physically plausible reconstructions for Dokdo.

To assess the physical consistency of the reconstructed Dokdo sea level series, we compared both the Mean- and IDW-based estimates against satellite altimetry sea level anomalies from the CMS at the Dokdo location. All timeseries were shifted vertically to facilitate intercomparison (

Figure 5). The reconstructions captured the seasonal cycle and interannual variability with strong coherence across the three datasets, especially from the early 2000s onward. Discrepancies in the early 1990s and post-2019 periods reflect a combination of factors, including early-year data sparsity, potential inconsistencies in vertical datum, and the coarser spatial resolution of gridded altimetry. Nonetheless, the strong agreement validates the statistical reconstructions and affirms their suitability for scientific analysis in data-sparse oceanic settings. To compare sea level variability at Dokdo with the 13 selected PSMSL tide gauge stations, we extracted satellite-derived sea level anomaly (SLA) from the CMS monthly product (1993–2023) at 13 PSMSL stations and the grid point closest to Dokdo (37.241° N, 131.865° E). All station series were resampled to a monthly resolution and visualized as vertically offset timeseries, using fixed offsets based on geodesic distance from Dokdo. A uniform negative offset was assigned to the Dokdo timeseries to clearly separate it from the others. The final figure includes station-specific labels and color coding, enabling visual comparison of seasonal and interannual variability patterns across the 14 series.

To evaluate the reliability of the reconstructed sea level data and assess consistency with independent observations, we compared the inverted barometric effect (IBE)-corrected PSMSL reconstructions with satellite altimetry estimates from the CMS (Equation (2) and

Figure 6). To correct the sea level for mean sea level atmospheric pressure:

where

,

,

, and

are observed mean sea level atmospheric pressure, reference pressure (e.g., 1013.25 hPa), seawater density, and gravity. Monthly CMS SLA data from 1993 to 2023 were extracted at the coordinates of the 13 selected PSMSL stations and at Dokdo, using nearest-neighbor sampling from the 0.25° × 0.25° gridded product (

Figure 7). For

Figure 8, we constructed an offset timeseries plot comparing the monthly sea level at each of the 14 stations (13 PSMSL + Dokdo) from both PSMSL and CMS. PSMSL records were first gap-filled using the ensemble mean of eight ML models and corrected for the IBE using ERA5 mean sea level atmospheric pressure data. Each station’s PSMSL timeseries was plotted with a solid line, and the corresponding CMS altimetry timeseries with a dashed line. To ensure visual clarity and facilitate inter-station comparison, vertical offsets were applied based on the geodesic distance from each station to Dokdo, with Dokdo plotted at the bottom using a fixed offset. Colors and line styles were standardized across both datasets for station-level coherence. The legend was simplified to include only station names (e.g., Ulleung, Saigo, …, Dokdo) in geodesic order. For

Figure 9, we specifically focused on Dokdo to compare the reconstructed sea level series derived from the IDW-weighted average of the 13 filled PSMSL stations (after IBE correction) with the CMS altimetry record at the same location. The IDW method applied geodesic distance-based weights to each contributing station. Both series were plotted together as monthly timeseries, using a red solid line for the reconstructed PSMSL (IDW) estimate and a black dashed line for the CMS altimetry product. This comparison enabled a direct assessment of temporal coherence, seasonal cycle fidelity, and interannual variability between the in situ-derived and satellite-based records.

To assess uncertainty in the reconstructed sea-level record at Dokdo, we implemented a Monte Carlo bootstrap framework with 1000 replicates. In each replicate, both the imputation models (drawn from the set of eight ML algorithms) and the contributing tide-gauge stations (drawn with replacement and inverse-distance weighting) were resampled. This procedure produced an ensemble of Dokdo reconstructions, from which we derived 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the monthly time series and the linear trend. For validation against CMS altimetry, we employed a 12-month moving-block bootstrap applied to paired IDW–altimetry series. This approach accounts for temporal autocorrelation and yielded 95% CIs for skill metrics, including RMSE, MAE, correlation, and R2. To test robustness during periods of sparse input data, we computed performance metrics for the Dokdo reconstruction against CMS altimetry in both the full overlap period (1993–2023) and the early period (1993–2000). Metrics were evaluated using RMSE, MAE, correlation, and R2, with uncertainty estimated from a 12-month moving-block bootstrap (N = 1000) to account for temporal autocorrelation.

3. Results

The original monthly sea level records from the 13 selected PSMSL tide gauge stations to Dokdo (

Figure 2) reveal a pronounced seasonal cycle, with both annual and semiannual components, and notable interannual fluctuations. However, these series also contain heterogeneous data gaps of varying lengths and temporal distribution, particularly during the early 1990s. Distant stations, such as Izuhara II and AWA SIMA, show more pronounced discontinuities and variability in amplitude, underlining the need for systematic gap-filling prior to spatial analysis and prediction efforts.

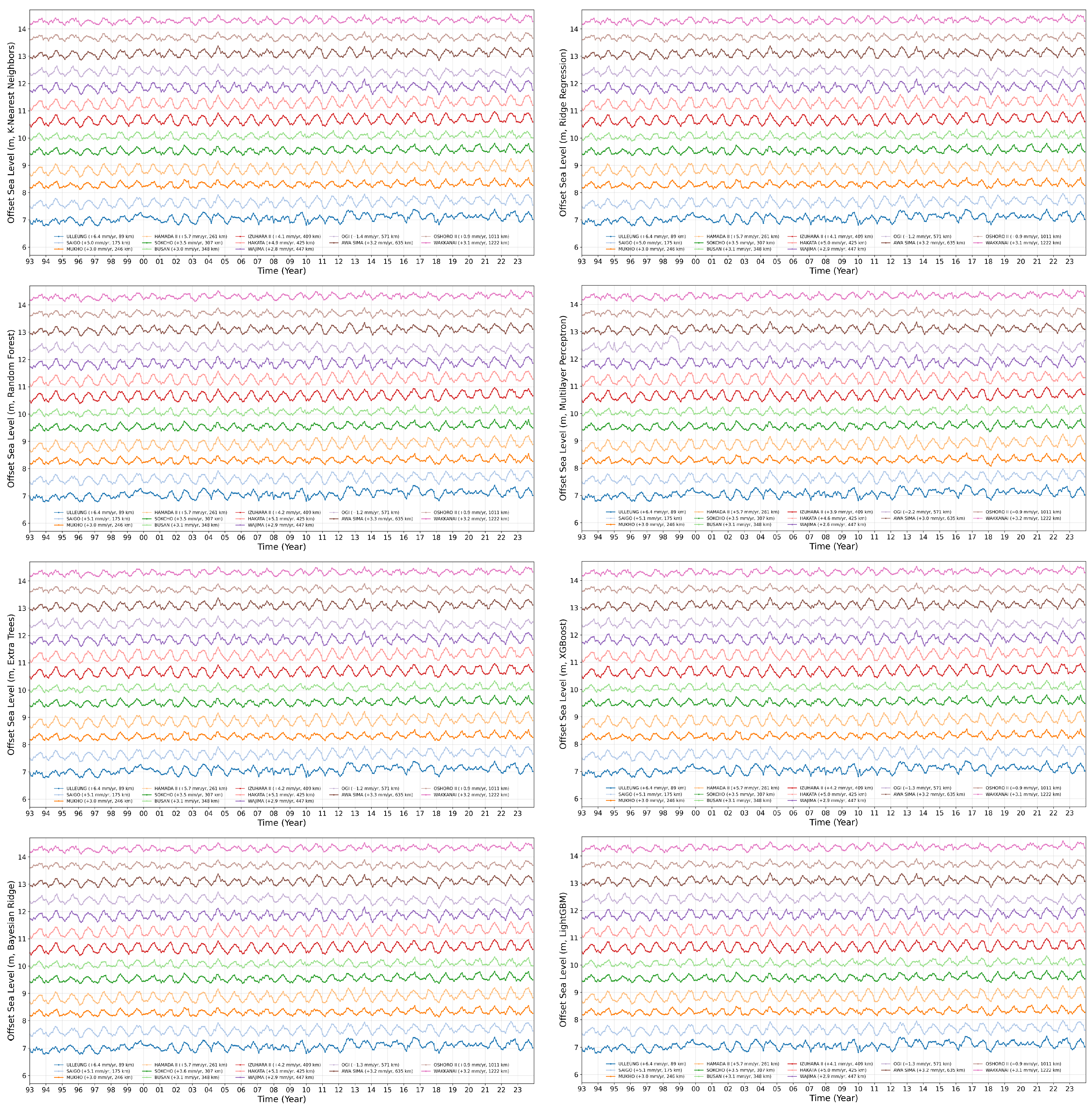

To address these issues, eight ML models, KNN, RF, ET, BR, Ridge, MLP, XGBoost, and LightGBM, were applied using a unified Iterative Imputer framework. As shown in

Figure 3, the reconstructed timeseries across all stations were continuous, physically realistic, and retained seasonal cycles. Minor differences among models were observed, especially in earlier periods where training data were sparse. Nonetheless, all models succeeded in reproducing coherent interannual patterns and reducing noise inherent in the original records.

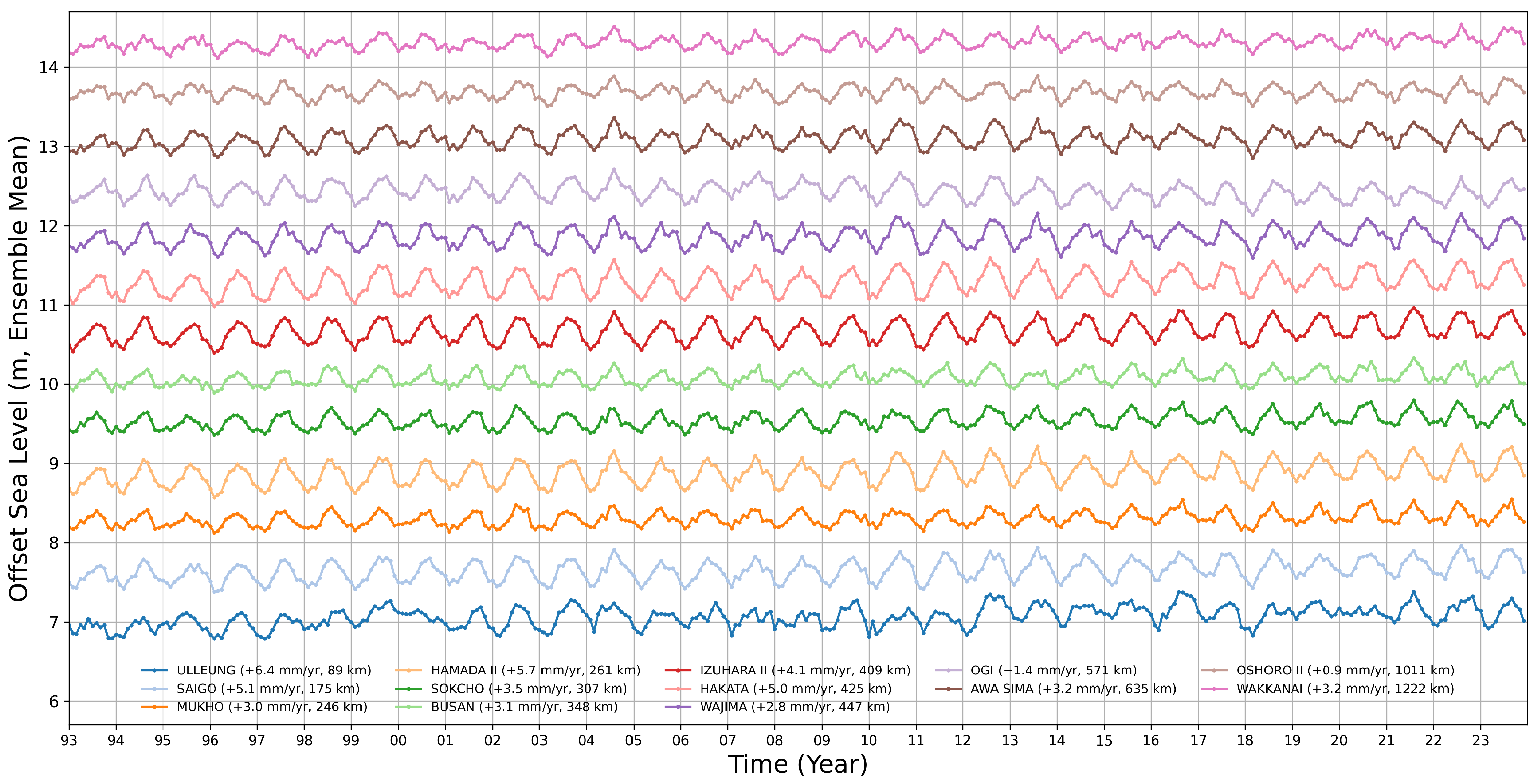

The ensemble mean of these imputed series (

Figure 4) provided a robust representation of regional sea level variability. By averaging across multiple model reconstructions, the ensemble approach smoothed model-specific idiosyncrasies while preserving meaningful signals. The timeseries clearly reflected multiyear trends and recurring seasonal fluctuations, reinforcing the reliability of the ensemble dataset for further spatial interpolation and analysis.

Using the ensemble-filled data from the 13 stations, sea level at Dokdo was reconstructed via a complementary approach: an IDW interpolation (

Figure 5). Both reconstructions yielded consistent seasonal and interannual signals, with prominent peaks during late summer (August–September) and troughs in winter, likely reflecting regional steric sea level responses to thermal expansion. The IDW-based estimate emphasized contributions from geographically closer stations such as Ulleung and SAIGO, leading to slightly enhanced short-term variability compared to the broader regional averaging in the mean-based approach. Despite this, both methods captured the long-term trend and seasonal modulation, supporting the validity of proxy-based Dokdo sea level estimation using surrounding tide gauge records.

3.1. Original Sea Level Records at 13 Selected Stations

Figure 2 presents the original monthly sea level records from 1993 to 2023 for the 13 tide gauge stations obtained from the PSMSL data. These stations were not chosen solely based on geographic distance to Dokdo, but rather because they are located in the surrounding region where vertical land motion is relatively small, making them more suitable as references for regional sea-level reconstruction. Geodesic distances from each station to Dokdo were computed and are annotated in

Figure 2. Each time series is vertically offset for clarity. The records exhibit consistent seasonal cycles across stations, underscoring strong regional oceanographic connectivity. However, significant temporal gaps, particularly during the 1990s and early 2020s, limit the direct calculation of long-term trends. These discontinuities were most frequent in the more distant and northern stations, highlighting the challenge of relying solely on raw observational datasets for regional sea level assessments.

3.2. Gap-Filled Ensemble Sea Level at 13 Stations

To address the limitations posed by missing data, we applied a suite of ML methods, including KNN, RF, ET, BR, Ridge, MLP, XGBoost, and LightGBM, to reconstruct the sea level time series. As shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, the ensemble mean of these model outputs provides a continuous and smoothed representation of sea level variability across all stations. Each reconstructed series preserves the original seasonal patterns while eliminating temporal gaps. The imputed datasets capture both the local variability and the broader climatological signals associated with steric and mass-driven processes in the East Sea and East China Sea. Importantly, slope estimates (in mm/yr) derived from the filled time series are indicated in the legends.

3.3. Dokdo Sea Level Prediction Using Regional Observations

Dokdo’s monthly sea level timeseries for 1993–2023 was estimated using the gap-filled records from the surrounding 13 stations through an interpolation strategy: inverse distance weighting.

Figure 5 compares these reconstructions. While both approaches reproduced the regional seasonal cycle and long-term variations, subtle differences emerged. The IDW prediction, favoring closer stations like Ulleung and Saigo, introduced higher-frequency fluctuations, whereas the mean-based prediction smoothed out local anomalies by averaging over all stations equally. These distinctions underscore the importance of methodological transparency in regional sea level predictions, especially when local processes may diverge from basin-wide trends.

Together, the results demonstrate that ML-enhanced imputation and ensemble interpolation offer a reliable framework for reconstructing realistic and continuous sea level timeseries in data-sparse locations like Dokdo. The predicted series preserves key regional signals and serves as a basis for future studies of coastal sea level change, hazard assessment, and climate variability.

Figure 6 provides validation using CMS satellite altimetry data at Dokdo, with all timeseries normalized and corrected for the IBE. The reconstructed Dokdo series—especially the IDW version—closely tracks altimetric variability, confirming physical realism and capturing regional seasonal dynamics.

Figure 7 illustrates the monthly sea level variability from 1993 to 2023 across 13 PSMSL tide gauge stations and Dokdo form CMS altimetry. After aligning the altimetry-derived SLA to the mean of the PSMSL ensemble, the Dokdo timeseries was plotted alongside the others with vertical offsets for clarity. All stations exhibit strong annual cycles and coherent interannual variability, suggesting regionally consistent oceanographic forcing. The altimetry-derived sea level at Dokdo shows a well-defined seasonal signal and multi-year fluctuations that align closely with nearby stations such as Ulleung, Saigo, and Mukho. This agreement supports the physical consistency of the CMS product and validates the use of satellite altimetry in reconstructing sea level trends at locations without in situ observations.

3.4. Comparison Between PSMSL and CMS Sea Levels

Figure 8 presents the monthly sea-level time series from 13 PSMSL tide-gauge stations and their corresponding CMS altimetry values, along with the reconstructed sea level at Dokdo shown at the bottom. For visualization, all timeseries were vertically offset, with each station represented by two curves: solid lines for IBE-corrected, gap-filled PSMSL records and dashed lines for CMS altimetry. The comparison demonstrates strong seasonal consistency across datasets, with annual and semiannual cycles well captured. However, differences emerge in interannual variability and long-term trends at several stations, particularly at more distant sites such as Wakkanai and Oshoro II. In contrast, stations geographically closer to Dokdo, including Ulleung and Saigo, show higher consistency between the two datasets, affirming their reliability as predictors in the reconstruction framework.

A key factor underlying residual differences between tide-gauge (TG) and satellite altimetry (SA) trends is Vertical Land Motion (VLM). Tide gauges measure relative sea level, which can be affected by subsidence, uplift, or tectonic processes, whereas altimetry provides absolute sea level referenced to a global geodetic datum. Without correcting for VLM, discrepancies between TG and SA records may reflect crustal motion rather than true oceanographic signals. Foundational global syntheses and reviews demonstrate that VLM can either amplify or attenuate relative sea-level change, underscoring its central role in reconciling TG–SA trends [

55,

56]. More recent studies highlight the added complexity of nonlinear VLM processes: probabilistic reconstructions reveal that tectonic activity, groundwater extraction, and surface loading can strongly modulate regional projections, altering relative sea level by up to 50 cm and increasing projection uncertainty by nearly 1 m in projections extending to the year 2150 [

57,

58]. At the same time, advanced noise reduction techniques applied to TG and SA records, combined with GNSS-based VLM corrections, have been shown to substantially improve consistency and reduce long-term uncertainties [

59]. Although VLM rates are relatively modest in the East Sea compared to tectonically active margins, explicitly accounting for them remains important when reconciling TG- and SA-based records. While the present study focuses on methodological development and validation, future extensions should systematically incorporate GNSS-constrained VLM corrections wherever available to achieve absolute consistency between tide-gauge reconstructions and altimetry-derived trends.

3.5. Comparison of Reconstructed and Satellite-Derived Sea Level at Dokdo

Figure 9 directly compares the IBE-corrected monthly sea level at Dokdo reconstructed via IDW from 13 surrounding PSMSL tide gauge stations with CMS satellite altimetry data at the Dokdo location for the period 1993–2023. Both timeseries exhibit consistent seasonal cycles, confirming the reliability of the interpolation and the physical basis of the seasonal signal. However, distinct differences emerge in interannual variability, particularly during the 1990s, early 2000s, and post-2015, where the CMS record shows greater amplitude fluctuations compared to the smoother PSMSL-derived reconstruction. These discrepancies are likely attributable to higher noise levels or transient mesoscale oceanographic features captured by satellite altimetry but unresolved by the IDW method, which emphasizes spatially averaged signals.

Despite these variations, the overall agreement between the two datasets supports the use of the IBE-corrected and ML-gap-filled PSMSL data as a realistic proxy for sea level variability at Dokdo. Trend analysis indicates that the reconstructed IDW series shows a slightly stronger rise of 4.64 mm/yr (R2 = 0.21) compared to 3.41 mm/yr (R2 = 0.10) in the CMS dataset. The lower R2 values reflect the influence of strong intra- and interannual variability, yet the close alignment of long-term trends reinforces the robustness of the reconstruction. These findings highlight the potential of tide gauge–based regional interpolation, especially when satellite records are limited by coastal proximity, data gaps, or geophysical corrections.

3.6. Uncertainty of Sea Level at Dokdo

The Monte Carlo bootstrap analysis (N = 1000) indicates that the typical monthly reconstruction uncertainty is ±3.3 cm, with narrower ranges in later years (median half-width: 3.7 cm in 1993–2000 vs. 3.2 cm in 2007–2023). The reconstructed 1993–2023 trend at Dokdo is 4.64 mm yr

−1 (95% CI: 3.57–5.20 mm yr

−1). Validation against CMS altimetry (

Table 3) shows an RMSE of 0.067 m (95% CI: 0.061–0.075 m), an MAE of 0.053 m (0.048–0.059 m), and a correlation of 0.743 (0.674–0.794) over the full 1993–2023 overlap, confirming robust agreement within the expected uncertainty bounds. Performance remains stable across decadal sub-periods, with RMSE values ranging from 0.064 to 0.073 m and correlation coefficients from 0.667 to 0.778, demonstrating that overfitting is minimal even in early sparse data windows.

To assess robustness under extreme conditions, we evaluated the reconstruction against CMS altimetry during (i) the strong 1997–1998 El Niño and (ii) the August–October 2003 typhoon season (

Table 4). During El Niño, the reconstruction achieved an RMSE of 0.096 m (0.092–0.116) and correlation r = 0.572 (0.060–0.897). During the 2003 typhoon season, the short evaluation window yielded higher variance but still strong correlation (RMSE = 0.110 m, MAE = 0.108 m, r = 0.916). These results suggest that the hybrid framework maintains predictive skill even during anomalous sea-level states. Taken together, the quantitative evaluation confirms that the Dokdo reconstruction achieves consistent agreement with altimetry (RMSE ≈ 0.07 m, MAE ≈ 0.05 m, r ≈ 0.7), with bootstrap confidence intervals confirming the stability of the metrics. The moving-block bootstrap further ensures robustness to temporal dependence, while Monte Carlo resampling of gauges and models demonstrates that no single predictor dominates the reconstruction.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates a comprehensive framework for reconstructing sea-level time series in data-sparse coastal environments, combining tide-gauge observations, inverse barometric correction, ML-based imputation, ensemble averaging, and geospatial interpolation. Applied to Dokdo in the East Sea, the framework successfully reproduced monthly sea level for 1993–2023 and showed robust agreement with satellite altimetry, including during anomalous events such as the 1997–1998 El Niño and the 2003 typhoon season.

Placing these results in a broader climate context is essential. While the 30-year window captures prominent events such as the 1997–1998 El Niño and the early-2000s PDO phase shift, it is too short to resolve full multi-decadal variability. Longer tide-gauge records from the Northwest Pacific (100–150 years) show rise rates broadly consistent with our Dokdo trend of 4.6 mm yr−1 (95% CI: 3.6–5.2 mm yr−1), but also reveal accelerations and slowdowns linked to ENSO, PDO, and IOD. Embedding our reconstruction within this broader variability highlights the need to extend the framework to longer records and integrate explicit climate-mode predictors.

Our results therefore provide two key insights: (i) the proposed hybrid framework is robust and transferable to data-sparse coastal sites, even under stress conditions such as ENSO anomalies or typhoon seasons, and (ii) integration with centennial tide-gauge reconstructions and reanalysis-based predictors will be critical to disentangle background sea-level rise from climate-driven variability, ultimately improving projections for marginal seas like the East Sea.

4.1. Ensemble-Based Reconstruction of Incomplete Sea Level Records

The diversity of missing data patterns across the 13 tide gauge records necessitated a robust and flexible imputation strategy. We implemented eight ML models, ranging from tree-based regressors (Random Forest, XGBoost, Extra Trees) to neural networks (MLP) and linear models (Bayesian Ridge, Ridge), within an IterativeImputer framework to reconstruct monthly sea level data. All models captured seasonal and interannual variability to varying degrees, and the ensemble mean across models further stabilized the timeseries by mitigating individual model biases and noise. As shown in

Figure 4, the ensemble retained physical realism and reproduced dominant regional signals while minimizing overfitting.

4.2. Spatial Interpolation and Sea Level Estimation at Dokdo

The imputed and ensemble-averaged timeseries were then used to estimate sea level at Dokdo, a location lacking long-term direct observations. An interpolation method was applied: IDW. The consistency between the two Dokdo reconstructions underscores the spatial coherence of regional sea level, with nearby stations like Ulleung and SAIGO exerting the strongest influence. Notably, the IDW reconstruction was more sensitive to local extremes (e.g., the sharp September 2023 peak), which aligns with its design to emphasize proximal stations. This trade-off between smoothing and localized sensitivity highlights the importance of interpolation choice for marginal-sea reconstructions.

4.3. Comparison with CMS Altimetry and Post-Correction Residuals

To validate the reconstructed sea level at Dokdo, we compared the IBE-corrected timeseries derived from PSMSL-based interpolation with satellite-derived sea surface height anomalies from CMS altimetry (

Figure 9). While overall agreement was strong, especially after IBE correction, residual amplitude differences remained. These stem from the inherent characteristics of each dataset: tide gauge-based reconstructions reflect nearshore processes, including coastal setup and wave-driven effects, while satellite altimetry provides spatially averaged offshore conditions. Consequently, discrepancies in timing and amplitude during high-energy periods reflect both observational scale differences and the smoothing effect of altimetric measurements. We note that applying the full DAC field, which accounts for both atmospheric pressure and wind-driven high-frequency ocean responses, can further improve the consistency of tide-gauge and satellite altimetry time series. In our study, the IB correction was applied as the dominant DAC term, but DAC fields (e.g., from PSMSL) were not available for all stations. Recent studies confirm that incorporating DAC improves tide-gauge/altimetry consistency and reduces uncertainty in long-term sea-level trends [

59]. Future extensions of our framework should therefore explicitly integrate DAC-corrected products to refine regional reconstructions in the Sea of Japan.

4.4. Benefits of ML and Ensemble Approaches

ML-based imputation proved particularly beneficial in reconstructing records from the early 1990s, a period with more frequent data gaps. Models such as Random Forest and XGBoost performed well in reproducing known values but risked overfitting post-2000, when fewer gaps remained. The ensemble mean not only generalized better but also reduced high-frequency noise and outlier sensitivity. This approach reinforces the value of ensemble learning in geophysical timeseries reconstruction, especially in semi-enclosed seas where station coverage is sparse and environmental variability is high.

4.5. Broader Implications and Methodological Transferability

The methodology developed in this study is adaptable to other coastal or marginal seas with limited tide gauge coverage. By combining data-driven reconstruction with physically informed corrections (e.g., IBE), the framework supports the generation of proxy sea level datasets where direct measurements are unavailable. These reconstructions can aid climate monitoring, coastal hazard forecasting, and satellite product validation. Furthermore, the ensemble-based workflow allows for modular updates as new stations, satellite datasets, or reanalysis products become available.

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

While the proposed framework demonstrates strong utility, several limitations remain. Reconstruction reliability is inherently dependent on the density and quality of available tide-gauge records. In its current form, the method produces deterministic outputs without explicit uncertainty bounds. To address this, we implemented a Monte Carlo bootstrap (N = 1000) to quantify uncertainty in both the monthly reconstructions and the long-term Dokdo trend, yielding an estimate of 4.6 mm yr−1 with a 95% confidence interval of 3.6–5.2 mm yr−1. Nevertheless, more advanced approaches, such as Bayesian ensembling, dropout-based uncertainty estimation, or integrated bootstrap schemes, should be explored in future work.

A further opportunity lies in expanding the predictor set beyond sea-level observations. Physically relevant variables such as sea surface temperature, wind stress, and steric height from ocean reanalysis products could improve physical realism, particularly during extreme events. While our framework is robust in its current form, incorporating such predictors may provide incremental benefits and should be prioritized in future reconstruction studies across marginal seas.

4.7. Toward Hybrid Sea Level Digital Twins

The convergence between corrected in situ reconstructions and satellite observations highlights the potential of hybrid approaches for digital twin development in coastal monitoring systems. By blending observational datasets, physical corrections, and ML-driven inference, this study lays the groundwork for scalable and interpretable sea level digital twins. Such systems can not only reconstruct historical records but also support real-time forecasting and long-term trend analysis in vulnerable regions like the East Sea.

Figure 10 summarizes the end-to-end workflow of this study, illustrating how machine learning-based imputation, IBE correction, and spatial interpolation were combined to reconstruct sea level at Dokdo in the absence of direct tide gauge measurements. The integration of eight ML models enabled robust reconstruction of missing values in the PSMSL dataset, while the IDW method leveraged spatial coherence from nearby stations. By applying IBE correction and validating the reconstructed Dokdo series against satellite altimetry, the framework not only ensures physical consistency but also demonstrates the viability of ML-driven coastal monitoring in data-sparse regions. Finally, while our hybrid reconstruction–altimetry framework demonstrates strong skill at the event to decadal scale, it is equally important to situate these results within longer-term climate variability, which we address in

Section 4.8.

4.8. Long-Term Climate Context

While this study focuses on a 31-year reconstruction (1993–2023), it is important to situate the results within the broader context of centennial- and millennial-scale sea-level variability. Long PSMSL tide-gauge records from the Northwest Pacific and global reconstructions extending back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries indicate rise rates of ~1.1 ± 0.7 mm yr

−1 during 1880–1935, increasing to ~1.8 ± 0.3 mm yr

−1 during 1936–2009, with an overall 20th-century trend of ~1.7 ± 0.2 mm yr

−1 (Figure 5 of [

60]). These centennial-scale rates are broadly consistent with our Dokdo estimate of 4.6 mm yr

−1 (95% CI: 3.6–5.2 mm yr

−1) for 1993–2023, reflecting both the recent acceleration and the superimposed influence of multi-decadal climate modes such as the PDO, IOD, and ENSO, which can modulate local sea-level trends by several millimeters per year [

36,

61].

Our 1993–2023 window captures only part of this variability, including the strong 1997–1998 El Niño and the early-2000s PDO phase shift, but is too short to resolve complete multi-decadal cycles. Recent reconstructions (e.g., [

36]) highlight how advanced statistical methods can separate long-term trend signals from climate-driven variability with ENSO- and PDO-related fluctuations capable of altering apparent sea-level rise by up to ~1 mm yr

−1 over 5-year windows. Paleo-sea-level reconstructions and geological evidence further suggest that the background rise over the past millennium has been slower but punctuated by episodes of natural variability, underscoring the need to link satellite-era trends with centennial- and millennial-scale perspectives.

Related efforts include the study of Lee et al. [

62], who developed a neural-network operator combining LSTM and data assimilation to reconstruct short-term (≤72 h) gaps in Korean tide-gauge records, achieving sub-centimeter accuracy. Their framework demonstrates the value of neural operators for high-frequency interpolation in coastal settings. In contrast, our approach targets multi-decadal reconstructions at an offshore site (Dokdo) by integrating tide-gauge data, satellite altimetry, and machine-learning imputation, with uncertainties explicitly quantified using Monte Carlo and moving-block bootstrap methods. These approaches are complementary: neural operators excel at resolving short-term continuity in dense observational networks, while our hybrid framework is designed to provide robust long-term reconstructions in data-sparse offshore environments.

Taken together, these studies provide a broader framework for situating our Dokdo reconstruction within the long-term trajectory of East Sea variability, linking the 30-year satellite era with centennial and millennial records. Future extensions of our methodology will therefore focus on assimilating longer tide-gauge records (>100 years where available), explicitly testing the added value of PDO/IOD indices and other reanalysis predictors, and benchmarking against paleoclimate reconstructions to strengthen projections for marginal seas.

5. Conclusions

This study developed and applied a hybrid reconstruction framework to generate a continuous, high-quality monthly sea level timeseries at Dokdo spanning 1993 to 2023. Leveraging in situ records from 13 nearby PSMSL tide gauge stations and an ensemble of advanced ML imputation techniques, we addressed the long-standing challenge of data sparsity in this strategically important region of the East Sea. By systematically filling data gaps and capturing spatial relationships among stations, the framework provides a robust and interpretable solution for reconstructing sea level variability in observationally limited coastal environments.

Several key insights emerged from this analysis. First, the original PSMSL station records, particularly those in northern locations, contained substantial missing segments, limiting their standalone use in regional sea level trend analysis. To overcome this, we implemented eight ML models spanning tree-based (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost), linear (e.g., Ridge, Bayesian Ridge), and neural network (e.g., MLP) approaches. These models successfully reconstructed realistic timeseries that preserved key features such as seasonal cycles and interannual variability. Second, ensemble averaging across these models effectively reduced individual model biases and smoothed high-frequency noise, producing stable and reliable inputs for spatial prediction. Using an inverse-distance weighting (IDW), we estimated sea level at Dokdo with high fidelity. These estimates showed strong agreement with neighboring stations, particularly Ulleung and Saigo, underscoring the spatial coherence of sea level in this region. Third, inverse barometric effect (IBE) correction using ERA5 mean sea level pressure further improved agreement with CMS satellite altimetry. Despite this improvement, some discrepancies remained, especially in high-frequency components, likely due to satellite limitations near the coast and unresolved local atmospheric and bathymetric influences.

Complementary to recent neural-operator approaches that achieve high accuracy in short-gap interpolation of tide-gauge data (e.g., [

62]), our framework provides robust long-term reconstructions in data-sparse offshore settings, underscoring the value of integrating multiple methodologies across different temporal and spatial scales. Our Dokdo reconstruction for 1993–2023 is also broadly consistent with centennial-scale tide-gauge reconstructions and paleo-sea-level evidence, which show an acceleration in regional and global sea-level rise since the early 20th century. By linking the satellite era with longer records extending over the past 100 to 1000 years, this study provides a bridge between short-term variability and long-term trends, strengthening the basis for future projections in the East Sea and other marginal seas.

Overall, this study demonstrates that a hybrid methodology, combining ML-based gap filling, ensemble modeling, spatial interpolation, and physical correction, can effectively reconstruct sea level in remote island and marginal sea settings. The workflow, illustrated in

Figure 10, is transparent, modular, and scalable, and can be readily applied to other regions with sparse observational coverage. Looking ahead, the framework can be extended to integrate satellite altimetry and physically relevant predictors from ocean reanalyses, such as steric height, wind stress, and sea surface temperature, which may further enhance reconstruction skill and physical realism, particularly for earlier time periods. In addition, extending the framework to include temporal forecasting using models like Prophet, Seasonal Auto Regressive Integrated Moving Average, and Long Short-Term Memory network may enable future scenario analysis, detection of seasonal anomalies, and preparation for extreme events. These developments can contribute to the advancement of digital twin systems for coastal monitoring and long-term adaptation planning in the context of accelerating sea-level rise.