Transboundary Management of a Common Sea in the Gulf of Venice: Opportunities from Maritime Spatial Planning in Italy and Slovenia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- In the context of the cross-border perspective, what are the elements introduced by the MSP in the area?

- How do the two plans address the three key sectors in the cross-border area?

- What is the added value of the new plans in the field of maritime spatial planning in both countries?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Area

2.2. Approach to the Analysis of MSP

- -

- We defined their structural composition using the descriptive research method. We focused on defining: (a) the basic starting points for the preparation of the plans, (b) the structure and content of the plans (provisions) and (c) the instruments for implementing the plans (measures).

- -

- We analysed the mutual similarities and differences between the two plans using the comparative method.

- -

- In a first step, we defined the basic concepts regarding the instruments and tools that determine the planning and management of activities and uses at sea.

- -

- In a second step, we examined the content of the individual provisions of the Italian and Slovenian plans in detail and carried out a mutual comparison. We referred to various sectoral materials used in the preparation process of the plans (e.g., the National Fisheries Management Plan, the Regulation on Special Protection Areas (Natura 2000), etc.).

3. Results

3.1. Key Elements of the MSP in the Two Countries

3.1.1. Key Elements of the Italian MSP

- Main elements

- Tools for the implementation of the plans

3.1.2. Key Elements of the Slovenian Plan

- Main elements

- (a)

- International commitments (conventions, protocols, etc.) in the field of sustainable development and protection of the marine environment, as well as joint/common development policies (e.g., fisheries, nature protection, etc.), in which individual sectoral spatial objectives are agreed at the EU level development.

- (b)

- The SDSS, which determines the fundamental spatial development goals at the national level.

- (c)

- More detailed sectoral development objectives at the national level.

- (d)

- Spatial development objectives at the local level, which are determined by municipalities’ spatial plans (such as the subsidiarity of the MSP).

- (e)

- The national Marine Environment Management Plan, which already includes various protection and administrative aspects and indicators for achieving and monitoring a good state of the marine environment.

- Implementation of the plan

- Directly through the provisions of the plan, which specify the spatial implementation conditions (graphically and textually) for achieving the goals of spatial development.

- Directly through the spatial measures defined in this plan.

- Directly through the management measures defined in this plan.

- Indirectly through spatial provisions, which are implemented in subordinate acts or documents within the jurisdiction of spatial planning authorities in the implementation of all activities, regimes and uses at sea.

3.1.3. Findings: Similarities and Differences Between the Two Plans

- (a)

- The process of plan preparation ensures decision-making on strategic spatial development objectives and the coordination of sectoral interests and development priorities. This can be described as the “process instruments of spatial planning for achieving spatial development objectives”.

- (b)

- The implementation of the plan itself enables the spatial regulation of activities and uses (locations, extent, conditions) and the implementation of monitoring the state of the space and the effectiveness of the implementation of the plan. This can be described as “spatial planning tools for achieving the objectives of spatial development”.

3.2. Instruments and Tools for the Management of Fisheries, Maritime Transport and Nature Conservation

3.2.1. The Italian Plans

- Fisheries

- (a)

- Direct transboundary effects: Regulation of fisheries on species, and international cooperation support sustainable resource management goals (e.g., improved state of fish stocks) in the study area.

- (b)

- Indirect transboundary effects: Fleet modernisation and energy efficiency bring economic benefits, helping offset present revenue losses from reduced catches and the fleet cuts. Such innovations would likely be adopted also by the Slovenian fisheries sector, thanks to cross-border exchanges between the operators of the sector.

- Maritime transport

- (a)

- Direct transboundary effects: Identifying, monitoring and managing hot spots of maritime pressures—including transboundary pollution, noise and megafauna corridors—would benefit the transboundary area through joint measures, e.g., for pollution reduction, protection of marine mammal corridors (e.g., cetaceans), and management of impact on coastal and benthic ecosystems.

- (b)

- Indirect transboundary effects: Solid waste management inventories and guidelines would provide a shared framework for waste reception and recycling, reducing incentives for illegal discharges and fostering circular economy practices at a cross-border level. Specific attention to plastic waste and marine litter as common issue is key. Expanding Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) and digital infrastructures would further enable cross-border digitalisation of logistics chains, enhancing interoperability and lowering environmental impacts.

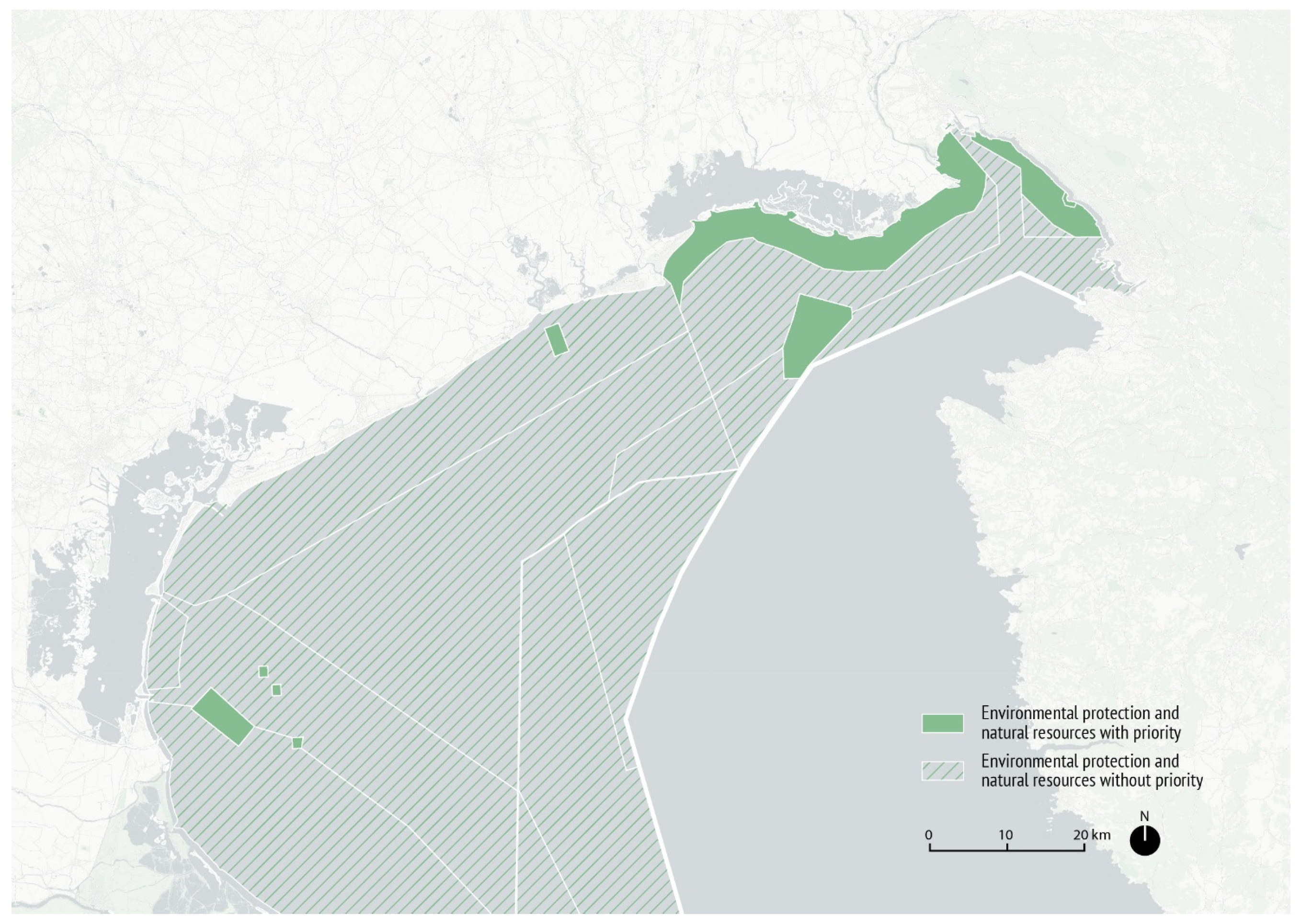

- Nature conservation

- (a)

- Direct transboundary effects: Expanding the MPA and Natura 2000 network on the Italian site would benefit the whole study area by enabling biodiversity corridors. Potential for cross-border MPAs/OECMs will be created, also thanks to the support of the MSP’s provisions in the two countries.

- (b)

- Indirect transboundary effects: Stronger transboundary cooperation will grow in key scientific areas such as habitats and species (e.g., marine megafauna) mapping, and in shared methods for cumulative impacts and user conflicts/synergies assessment.

3.2.2. The Slovenian Plan

- Fisheries

- (a)

- Direct transboundary effects: The regulation of fisheries on individual fish species ensures the achievement of international sustainable natural resource management goals.

- (b)

- Indirect transboundary impacts: Measures to limit marine pollution (litter) help to limit the pollution potential of the wider area.

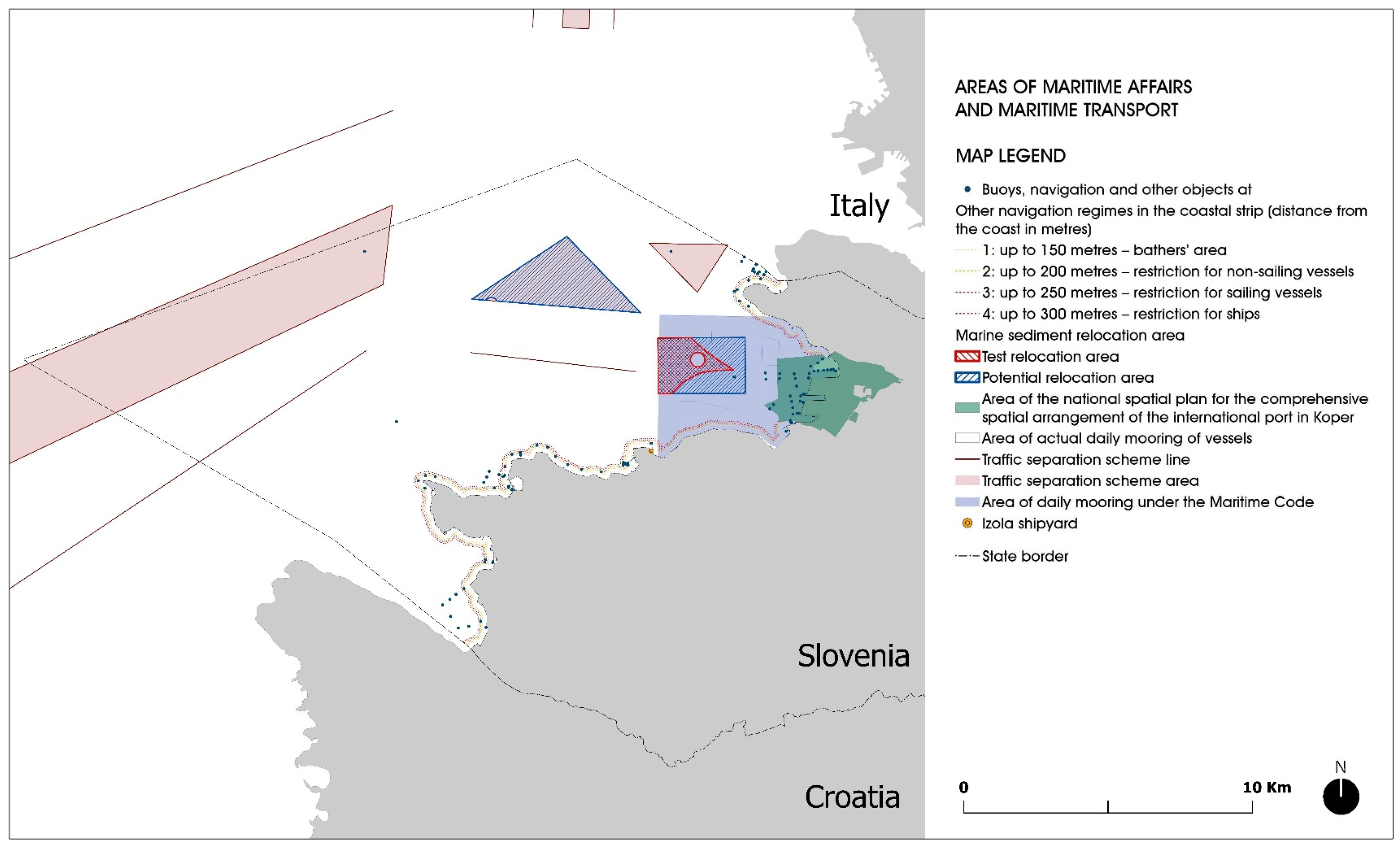

- Maritime transport

- (a)

- Direct transboundary impacts: The permanent existence of the separate navigation system and the measures for the coordinated implementation of all other nautical activities ensure the necessary standards for safe navigation in the Gulf of Trieste.

- (b)

- Indirect transboundary impacts: Measures to limit marine litter and measures for the controlled movement of marine sediments contribute to limiting the pollution potential of the wider area.

- Nature conservation

- (a)

- Direct transboundary effects: Measures on fishing restrictions and joint protection of the detrital seabed at the three-country border (SI-IT-HR).

- (b)

- Indirect transboundary impacts: Virtually all other measures aimed at additional extensions of protection regimes have a positive impact on the wider area.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Added Value and Persisting Challenges of MSP for Italy

4.2. The Added Value of Marine Spatial Planning for Slovenia

- Comparative Overview: Added Value of MSP in Italy and Slovenia

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union Directive 2014/89/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 2014 Establishing a Framework for Maritime Spatial Planning. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32014L0089 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Maes, F. The international legal framework for marine spatial planning. Mar. Policy 2008, 32, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gissi, F.; Fraschetti, S.; Micheli, F. Incorporating change in marine spatial planning: A review. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 92, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidas, D. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, the European Union and the Rule of Law: What is going on in the Adriatic Sea? Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 2009, 24, 1–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valinger Sluga, M.; Ažman Momirski, L. Planning ports in proximity: Koper and Trieste after 1945. Plan. Perspect. 2024, 39, 725–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, S.; Alves, F.L.; O’Mahony, C.; Gomez, M.; Rooney, A.; Almodovar, M.; Gee, K.; Vivero, J.L.S.; Gonçalves, J.M.S.; Fernandes, M.d.L.; et al. Transboundary dimensions of marine spatial planning: Fostering inter-jurisdictional relations and governance. Mar. Policy 2016, 65, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodie, J.R.; Sielker, F. Transboundary Marine Spatial Planning in European Sea Basins: Experimenting with Collaborative Planning and Governance. Plan. Pract. Res. 2022, 37, 317–332. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/02697459.2021.2015855?needAccess=true (accessed on 28 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bastardie, F.; Angelini, S.; Bolognini, L.; Fuga, F.; Manfredi, C.; Martinelli, M.; Nielsen, J.R.; Santojanni, A.; Scarcella, G.; Grati, F. Spatial planning for fifisheries in the Northern Adriatic: Working toward viable and sustainable fifishing. Ecosphere 2017, 8, e01696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaucha, J.; Gee, K.; Ramieri, E.; Neimane, L.; Alloncle, N.; Blažauskas, N.; Calado, H.; Cervera-Núñez, C.; Marohnić Kuzmanović, V.; Stancheva, M.; et al. Implementing the EU MSP Directive: Current status and lessons learned in 22 EU Member States. Mar. Policy 2025, 173, 106535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troha, N. Yugoslav-Italian Border and the Issue of Slovenian Access to the Sea. In Between the House of Habsburg and Tito. A Look at the Slovenian Past 1861–1980; Perovšek, J., Godeša, B., Eds.; Institut of Contemporary History: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2016; pp. 203–214. Available online: https://www.sistory.si/media/legacy/publikacije/36001-37000/36073/vpogledi_14-splet.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Bufon, M. Cross-Border Aspects of Sustainable Development in the Adriatic Region. Int. J. Euro-Mediterr. Stud. 2013, 5, 121–132. Available online: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs40321-013-0009-9# (accessed on 28 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Barić Punda, V.; Brkić, Z. The protection and conservation of the Meditertanean sea witha a special reference to coastal states which are members of the EU/Zaštita i očuvanje Sredozemnog mora s posebnim osvrtom na obalne države članice EU. In Zbornik radova Pravnog fakulteta u Splitu; Barić Punda, V., Ed.; Sveučilište u Splitu, Pravni fakultet: Split, Hrvatska, 2007; Volume 44, pp. 53–65. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/37653 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Bojinović Fenko, A.; Urlić, A. Political Criteria vs. Political Conditionality: Comparative Analysis of Slovenian and Croatian European Union Accession Processes. Croat. Int. Relat. Rev. 2015, 21, 107–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackelworth, P.; Fortuna, C.M.; Antoninić, M.; Holcer, D.; Abdul Malak, D.; Attia, K.; Bricelj, M.; Guerquin, F.; Marković, M.; Nunes, E.; et al. Ecologically and Biologically Significant Areas (EBSAs) as an enabling mechanism for transboundary marine spatial planning. Marine Policy. 2024, 166, 106231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čok, G.; Mezek, S.; Urh, V.; Repe, B. Contribution of International Projects to the Development of Maritime Spatial Planning Structural Elements in the Northern Adriatic: The Experience of Slovenia. Water 2021, 13, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritime Spatial Plans of Italy (MSP)/Piani di Gestione dello Spazio Marittimo. Official Gazette of the Italian Republic—GU Serie Generale n.235, 07-10-2024. Ministerial Decree (Ministry of Infrastructures and Transport) n. 237, 25-09-2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.sid.mit.gov.it/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Maritime Spatial Plan of Slovenia (MSP)/Pomorski Prostorski plan Slovenije (PPP). Official Gazette of Republic of Slovenia, No. 116/16. 2021. Available online: https://dokumenti-pis.mop.gov.si/javno/veljavni/PPP2192/1/English/MSP_Slovenia.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Niavis, S.; Papatheochari, T.; Kyratsoulis, T.; Coccossis, H. Revealing the potential of maritime transport for ‘Blue Economy’ in the Adriatic-Ionian Region. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2017, 5, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarcella, G.; Grati, F.; Raicevich, S.; Russo, T.; Gramolini, R.; Scott, R.; Polidori, P.; Domenichetti, F.; Bolognini, L.; Giovanardi, O.; et al. Common sole in the Northern Adriatic Sea: Possible spatial management scenarios to rebuild the stock. J. Sea Res. 2014, 89, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilakopoulos, P.D.; Maravelias, C.; Tserpes, G. The alarming decline of Mediterranean fish stocks. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, 1643–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, E.; Anelli Monti, M.; Mangano, M.C.; Raffaetà, A.; Gianluca, S.; Silvestri, C.; Pranovi, F. Temporal and spatial patterns of trawl fishing activities in the Adriatic Sea (Central Mediterranean Sea, GSA17). Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2020, 192, 105231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falace, A.; Kaleb, S.; Curiel, D.; Miotti, C.; Galli, G.; Querin, S.; Ballesteros, E.; Solidoro, C.; Bandelj, V. Calcareous Bio-Concretions in the Northern Adriatic Sea: Habitat Types, Environmental Factors that Influence Habitat Distributions, and Predictive Modelling. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianni, F.; Turicchia, E.; Abbiati, M.; Calcinai, B.; Caragnano, A.; Ciriaco, S.; Costantini, F.; Kaleb, S.; Piazzi, L.; Puce, S.; et al. Spatial patterns and drivers of benthic community structure on the northern Adriatic biogenic reefs. Biodivers. Conserv. 2023, 32, 3283–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearzi, G.; Bonizzoni, S.; Genov, T.; Notarbartolo di Sciara, G. Whales and dolphins of the Adriatic Sea: Present knowledge, threats and conservation. Acta Adriat. 2024, 65, 75–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramieri, E.; Bocci, M.; Brigolin, D.; Campostrini, P.; Carella, F.; Fadini, A.; Farella, G.; Gissi, E.; Madeddu, F.; Menegon, S.; et al. Designing and implementing a multi-scalar approach to Maritime Spatial Planning: The case study of Italy. Mar. Policy 2024, 159, 105911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, J.A.; Heithaus, M.; McCauley, D.J.; Rasher, D.B.; Worm, B. Megafaunal impacts on structure and function of ocean ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Env. Resour. 2016, 41, 83–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kira, K.; Blazauskasb, N.; Dahlc, K.; Gökec, C.; Hasslerd, B.; Kannena, A.; Leposae, N.; Morfe, A.; Strande, H.; Weigf, B.; et al. Can tools contribute to integration in MSP? A comparative review of selected tools and approaches. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 179, 104834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jay, S. Transboundary marine spatial planning across Europe: Trends and priorities in nearly two decades of project work. Mar. Policy 2020, 118, 104012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansong, J.O.; Ritchie, H.; Gee, K.; McElduff, L.; Zaucha, J. Pathways towards integrated cross-border marine spatial planning (MSP): Insights from Germany, Poland and the island of Ireland. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2022, 31, 2446–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansong, J.O.; McElduff, L.; Ritchie, H. Institutional integration in transboundary marine spatial planning: A theory-based evaluative framework for practice. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2021, 202, 105430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Burg, S.W.K.; Skirtun, M.; Van der Valk, O.; Rossi Cervi, W.; Selnes, T.; Neumann, T.; Steinmann, J.; Arora, G.; Roebeling, P. Monitoring and evaluation of maritime spatial planning—A review of accumulated practices and guidance for future action. Mar. Policy 2023, 150, 105529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafael, T.; Cabral, H.; Mourato, J.; Ferrăo, J. Marine spatial planning: A systematic literature review on its concepts, approaches, and tools (2004–2020). Marit. Stud. 2024, 23, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelzenmüller, V.; Cormier, R.; Gee, K.; Shucksmith, R.; Gubbins, M.; Yates, K.L.; Morf, A.; Nic Aonghusa, C.; Mikkelsen, E.; Tweddle, J.F.; et al. Evaluation of marine spatial planning requires fit for purpose monitoring strategies. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 278, 111545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Instruments | |

|---|---|

| Scope of the instruments | |

| Definition of institutional context and context conditions | Legislative Decree 17 October 2016, n. 201

|

| Guidelines for MSP preparation and their key contents | Decree of the Presidency of the Council of Ministries 1 December 2017

|

| Plan of the Sea 2023–2025 | The strategy for the sustainable management of marine resources and the sustainable development of the Italian maritime system

|

| Coordination of activities at sea | MSP

|

| Tools | |

| Scope of the tools | |

| Spatial identification of areas for activities and uses (zoning) | Identification of sub-areas, identification of Planning Units (PUs) and their attribution to typology, identification of priority, limited or reserved uses |

| Implementation provisions | Management measures identified at the national level and linked to strategic objectives |

| More spatially detailed provisions | Specific objectives and related measures identified at the regional level by regional authorities |

| Monitoring of the implementation of the plan | Monitoring system and indicators |

| Instruments | |

|---|---|

| Scope of the instruments | |

| Definition of institutional context |

|

| Guidelines for MSP preparation |

|

| I. Process instruments: | Managing the coordination of interests in the space

|

| Tools | |

| Scope of the tools | |

| II. Implementation tools | Location and scope

|

| Fisheries | Maritime Transport | Nature Conservation |

|---|---|---|

| Main subjects of planning and management | ||

|

|

|

| Tools | ||

|

|

|

| Expected result | ||

|

|

Applying a coherent Ecosystem Based Approach (EBA)

|

| No. | Status | Content/Summary of the Provision (Current MSP) |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial measures: | ||

| 1 | S1 | Spatially defined fishing areas (regimes and restrictions) |

| 2 | S2 | The possibility of installing a pilot (test) artificial vertical/horizontal underwater structure is permitted. |

| Management measures: | ||

| 1 | S4 | Required mutual coordination with other uses, in case of simultaneous implementation |

| 2 | S3 | Required verification of eligibility and consequences of mullet fishing |

| 3 | S3 | Required verification of gilthead sea bream catches in the areas of fishing reserves and shellfish farms |

| 4 | S5 | The appropriate number of special permits (for catching mullet and gilthead sea bream) is determined |

| 5 | S5 | The competent authorities should supervise the prohibited fishing methods |

| 6 | S6 | Conditions for the separate collection of waste from fishing activities are required in fishing ports |

| 7 | S6 | Studying the possibilities and ensuring the appropriate conditions (ecological and other) for the re-fishing of species that were traditionally fished (tuna, lobster, eel, etc.) |

| 8 | S6 | Arrange the possibilities and provide everything necessary for the cultivation of indigenous species with the aim of repopulation |

| 9 | S6 | The location for the temporary storage of waste vessels must be determined |

| No. | Status | Content/Summary of the Provision (Current MSP) |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial measures: | ||

| 1 | S1 | Permanent preservation of the scope of the joint traffic separation system in the Gulf of Trieste |

| 2 | S1 | Two potential locations for relocation of marine sediment due to the deepening of navigation routes and the international transport port in Koper are envisaged (test and permanent area) |

| 3 | S6 | Relocation of marine sediment is carried out in case of demonstrably acceptable impacts on the space and environment (nationally defined procedure and conditions) |

| 4 | S2 | Permanently preserve and develop the existing legal location of small service shipyards for the maintenance of boats and small passenger vessels |

| 5 | S2 | The possibility of expansion of ports for special purposes is allowed (need/process to prepare a coordinated operational plan for the development of ports at the local level) |

| 6 | S2 | Expansion of municipal berths, marinas and piers for the landing of passenger transport, a port for international public passenger transportation, possible with the prior preparation of expert grounds, including environmental impact assessment, verification of capacities in the hinterland, etc. |

| Management measures: | ||

| 1 | S3 | The separation space of the exit navigation corridor from the port of Koper is increased in the south-eastern direction from the boundary of the Debeli Rtič Landscape Park near Valdoltra by adjusting it with the protection regimes in the Decree on the Debeli Rtič Landscape Park. |

| 2 | S6 | Special activities in the field of maritime transport, sport, tourism, leisure and other nautical recreational activities (e.g., regattas, fishing competitions, labelling special anchoring and safe navigation regimes in the season, determining the permitted locations for the arrival of non-motor tourist vessels along beaches, etc.) can be carried out based on a permit by the Maritime Administration. |

| 3 | S4 | Links between providers of tourist services and public passenger transportation at sea and on land are established and promoted. |

| 4 | S5 | The implementation of the legislative provision stipulating that sailing within 250 metres off the coast and navigation with motor vessels within 200 metres off the coast are not permitted must be supervised. The speed of vessels should be restricted. |

| 5 | S5 | Registering sunken vessels and appropriately emptying fuel tanks—preventing sea pollution. |

| 6 | S6 | The owner of a waste vessel must ensure further processing of the vessel or its removal. Temporary storage for the vessel needs to be ensured until it is delivered to an authorised collector of waste. In the area of coastal municipalities, a location for the temporary storage of waste vessels needs to be determined, together with the utility companies responsible for waste collection. |

| No. | Status | Content/Summary of the Provision (Current MSP) |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial and management measures: | ||

| 1 | S3 | In the navigation corridor from the port of Koper around Debeli Rtič, navigation is restricted for cargo ships and other vessels longer than 24 m within a distance of 400 metres from the coast. |

| 2 | S1 | The boundary of the anchorage area for cargo ships along the coast of Debeli Rtič is additionally moved away from the boundary of the Debeli Rtič Landscape Park. |

| 3 | S3 | Restrictions on navigation and moving of the boundary of the anchorage area are made in agreement with the Maritime Administration (for example, internal rules of the Maritime Administration). |

| 4 | S3 | The area of the Dragonja River estuary is determined as an especially sensitive environment, and the conditions for nature conservation will be determined with an act (change in the Decree on Sečovlje Salina Nature Park is possible). In the area of the Dragonja River estuary, motor vessel navigation and anchoring are forbidden except for the needs of mariculture and the management of the Sečovlje Salina Nature Park. |

| 5 | S3 | The area of the underwater sandbank on the western side of Punta and the ridge (step) on the eastern side are protected with an act or included in a new act on the protection of the Cape Madona Natural Monument. Proper management should be ensured. |

| 6 | S3 | The protection area of Strunjan Landscape Park at sea should be extended. |

| 7 | S3 | Fishing with bottom trawls is limited in the area of the detrital seabed near the tri-border with Italy and Croatia at sea. Only the use of a ‘volantina’ type bottom trawl is permitted. After the fishing exception period expires, the reasons for the foundation or insurance should be verified. |

| 8 | S6 | Expert bases with regard to cross-border protection of the detrital seabed are prepared. |

| 9 | S6 | Additional areas of sensitive habitat types, where anchoring is prohibited, should be identified. |

| 10 | S4 | In the area of the expansion of the Natura 2000 site into the sea segment, coordination needs to be performed between the nature conservation sector and the sector of commercial and leisure fishing in terms of consensus on fishing. |

| Spatial Planning and Management Tools | ||

|---|---|---|

| Fisheries | Maritime Transport | Nature Conservation |

| Main subjects of planning and management (regulation) | ||

|

|

|

| How to–which tools? | ||

|

|

|

| Outcomes/Efficiency | ||

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Čok, G.; Bocci, M.; Carella, F.; Ramieri, E.; Plazar, M. Transboundary Management of a Common Sea in the Gulf of Venice: Opportunities from Maritime Spatial Planning in Italy and Slovenia. Water 2025, 17, 2812. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17192812

Čok G, Bocci M, Carella F, Ramieri E, Plazar M. Transboundary Management of a Common Sea in the Gulf of Venice: Opportunities from Maritime Spatial Planning in Italy and Slovenia. Water. 2025; 17(19):2812. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17192812

Chicago/Turabian StyleČok, Gregor, Martina Bocci, Fabio Carella, Emiliano Ramieri, and Manca Plazar. 2025. "Transboundary Management of a Common Sea in the Gulf of Venice: Opportunities from Maritime Spatial Planning in Italy and Slovenia" Water 17, no. 19: 2812. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17192812

APA StyleČok, G., Bocci, M., Carella, F., Ramieri, E., & Plazar, M. (2025). Transboundary Management of a Common Sea in the Gulf of Venice: Opportunities from Maritime Spatial Planning in Italy and Slovenia. Water, 17(19), 2812. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17192812