From Silos to Synergy: Improving Coordination in Local Flood Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Analytic Framework

3. Methods and Data

3.1. Case Selection

3.2. Methodology

4. Results from Qualitative Analysis

4.1. The Role of Municipalities in Flood Risk Management in the Federal System

4.2. Municipal Actors in Flood Management

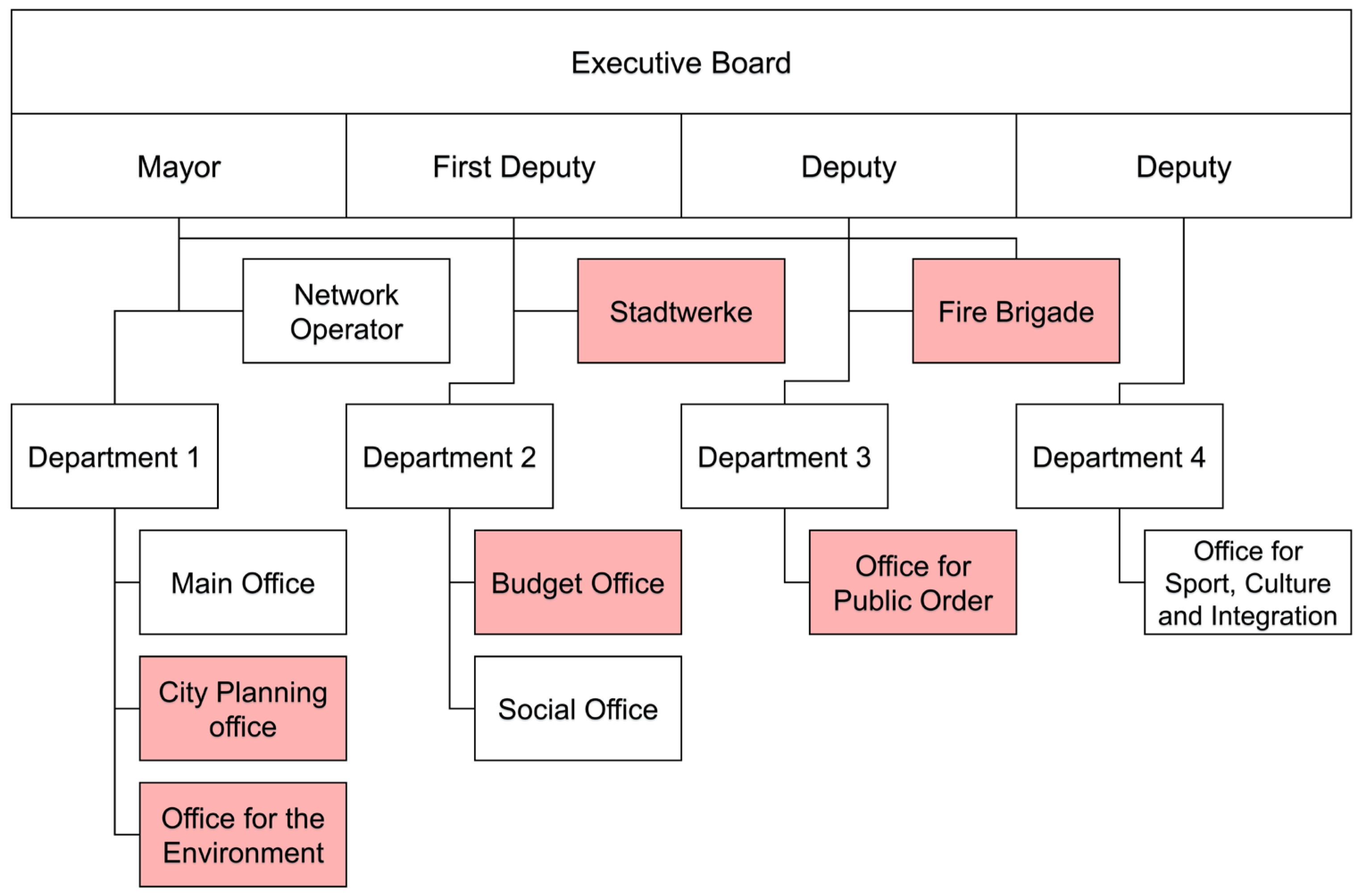

4.3. Concepts and Instruments in Place

5. Discussion

5.1. Barriers to Coordination

5.2. Options for Enhancing Coordination

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hirabayashi, Y.; Mahendran, R.; Koirala, S.; Konoshima, L.; Yamazaki, D.; Watanabe, S.; Kim, H.; Kanae, S. Global Flood Risk under Climate Change. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, A.C.; Kay, A.L.; Sayers, P.B. Climate Change Impacts on Flood Peaks in Britain for a Range of Global Mean Surface Temperature Changes. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2023, 16, e12863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Kanae, S.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Handmer, J.; Nicholls, N.; Peduzzi, P.; Mechler, R.; Bouwer, L.M.; Arnell, N.; Mach, K.; et al. Flood Risk and Climate Change: Global and Regional Perspectives. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2014, 59, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T. Deutscher Wetterdienst Analysiert Häufigkeit und Stärke Extremer Niederschlagsereignisse. 2021. Available online: https://www.dwd.de/DE/presse/pressekonferenzen/DE/2021/PK_26_08_2021/statement_fuchs_pk.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3 (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- European Environmental Agency. Europe’s Changing Climate Hazards-an Index-Based Interactive EEA Report; European Environmental Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ajjur, S.B.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Exploring Urban Growth–Climate Change–Flood Risk Nexus in Fast Growing Cities. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.D.; Hutchins, M. The Impacts of Urbanisation and Climate Change on Urban Flooding and Urban Water Quality: A Review of the Evidence Concerning the United Kingdom. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2017, 12, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dordi, T.; Henstra, D.; Thistlethwaite, J. Flood Risk Management and Governance: A Bibliometric Review of the Literature. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2022, 15, e12797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, C.; Pidgeon, N. From ‘Flood Defence’ to ‘Flood Risk Management’: Exploring Governance, Responsibility, and Blame. Environ. Plann. C Gov. Policy 2011, 29, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegger, D.L.T.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Dieperink, C.; Wiering, M.; Raadgever, G.T.T.; Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W. Assessing Stability and Dynamics in Flood Risk Governance: An Empirically Illustrated Research Approach. Water Resour. Manag. 2014, 28, 4127–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matczak, P.; Hegger, D.L.T. Flood Risk Governance for More Resilience—Reviewing the Special Issue’s Contribution to Existing Insights. Water 2020, 12, 2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.; Westbrook, C.J.; Noble, B.F. A Review of the Flood Risk Management Governance and Resilience Literature. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2018, 11, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClymont, K.; Morrison, D.; Beevers, L.; Carmen, E. Flood Resilience: A Systematic Review. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 1151–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mees, H.; Alexander, M.; Gralepois, M.; Matczak, P.; Mees, H. Typologies of Citizen Co-Production in Flood Risk Governance. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 89, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restemeyer, B.; Woltjer, J.; Van Den Brink, M. A Strategy-Based Framework for Assessing the Flood Resilience of Cities—A Hamburg Case Study. Plan. Theory Pract. 2015, 16, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awah, L.S.; Belle, J.A.; Nyam, Y.S.; Orimoloye, I.R. A Participatory Systems Dynamic Modelling Approach to Understanding Flood Systems in a Coastal Community in Cameroon. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 101, 104236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffers, J.M. Building Constituencies for Flood Risk Management: Critical Insights from a Flood Defences Dispute in Ireland. Risk Hazard Crisis Public Policy 2022, 13, 356–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.; Priest, S.; Mees, H. A Framework for Evaluating Flood Risk Governance. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 64, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessen, P.P.J.; Hegger, D.L.T.; Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W.; Crabbé, A.; Larrue, C.; Matczak, P.; Pettersson, M.; Priest, S.; Suykens, C.; et al. Governance Strategies for Improving Flood Resilience in the Face of Climate Change. Water 2018, 10, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenveld, A.; Van Buuren, A. Flood Risk and Resilience in the Netherlands: In Search of an Adaptive Governance Approach. Water 2019, 11, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbeck, R.; Seher, W.; Grüneis, H.; Herrnegger, M.; Junger, L. Conflicting and Complementary Policy Goals as Sectoral Integration Challenge: An Analysis of Sectoral Interplay in Flood Risk Management. Policy Sci. 2023, 56, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Boer, J.; Dieperink, C.; Mukhtarov, F. Social Learning in Multilevel Flood Risk Governance: Lessons from the Dutch Room for the River Program. Water 2019, 11, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilgen, S.; Sengers, F.; Wardekker, A. City-To-City Learning for Urban Resilience: The Case of Water Squares in Rotterdam and Mexico City. Water 2019, 11, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbeck, R.; Löschner, L.; Pelaez Jara, M.; Pregernig, M. Exploring Science–Policy Interactions in a Technical Policy Field: Climate Change and Flood Risk Management in Austria, Southern Germany, and Switzerland. Water 2019, 11, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E. Adapting to Climate Change at the Local Level: The Spatial Planning Response. Local Environ. 2006, 11, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storbjörk, S. Governing Climate Adaptation in the Local Arena: Challenges of Risk Management and Planning in Sweden. Local Environ. 2007, 12, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieperink, C.; Hegger, D.L.T.; Bakker, M.H.N.; Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Green, C.; Driessen, P.P.J. Recurrent Governance Challenges in the Implementation and Alignment of Flood Risk Management Strategies: A Review. Water Resour Manag. 2016, 30, 4467–4481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Hegger, D.L.T.; Matczak, P.; Driessen, P.P.J. Flood-Risk Reduction: Structural Measures and Diverse Strategies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 12321–12325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergsma, E. The Development of Flood Risk Management in the United States. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 101, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegger, D.L.T.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Wiering, M.; Van Rijswick, H.F.M.W.; Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Matczak, P.; Crabbé, A.; Raadgever, G.T.; Bakker, M.H.N.; Priest, S.J.; et al. Toward More Flood Resilience: Is a Diversification of Flood Risk Management Strategies the Way Forward? Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Growe, A. Research on Small and Medium-Sized Towns: Framing a New Field of Inquiry. World 2021, 2, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trein, P.; Biesbroek, R.; Bolognesi, T.; Cejudo, G.M.; Duffy, R.; Hustedt, T.; Meyer, I. Policy Coordination and Integration: A Research Agenda. Public Adm. Rev. 2021, 81, 973–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelling, T.C. The Strategy of Conflict; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Cronk, L.; Leech, B.L. Meeting at Grand Central: Understanding the Social and Evolutionary Roots of Cooperation; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-691-15495-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, R.H.; Clark, J.P.; Giordano, P.C.; Johnson, P.V.; van Roekel, M. Patterns of Interorganizational Relationships. Adm. Sci. Q. 1977, 22, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, T.W.; Crowston, K. The Interdisciplinary Study of Coordination. ACM Comput. Surv. 1994, 26, 87–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, T.H. Why Is the Intelligence Community So Difficult to Redesign? Smart Practices, Conflicting Goals, and the Creation of Purpose-Based Organizations. Governance 2007, 20, 401–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koop, C.; Lodge, M. Exploring the Co-Ordination of Economic Regulation. J. Eur. Public Policy 2014, 21, 1311–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.; Lægreid, P. The Challenge of Coordination in Central Government Organizations: The Norwegian Case. Public Organ. Rev. 2008, 8, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, T. The Blind Spots of Public Bureaucracy and the Politics of Non Coordination; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-76671-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lukat, E.; Lenschow, A.; Dombrowsky, I.; Meergans, F.; Schütze, N.; Stein, U.; Pahl-Wostl, C. Governance towards Coordination for Water Resources Management: The Effect of Governance Modes. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 141, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Knieper, C. The Capacity of Water Governance to Deal with the Climate Change Adaptation Challenge: Using Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis to Distinguish between Polycentric, Fragmented and Centralized Regimes. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 29, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharpf, F.W. Komplexität als Schranke der politischen Planung. In Gesellschaftlicher Wandel und Politische Innovation; Faul, E., Ed.; Politische Vierteljahresschrift Sonderheft 4/1972; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1972; pp. 168–192. ISBN 978-3-531-11159-9. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, D. Organising the Political Coordination of Knowledge and Innovation Policies. Sci. Public Policy 2008, 35, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, L. International Policy Co-Ordination and Public Management Reform. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 1994, 60, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candel, J.J.L.; Biesbroek, R. Toward a Processual Understanding of Policy Integration. Policy Sci. 2016, 49, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejudo, G.M.; Michel, C.L. Addressing Fragmented Government Action: Coordination, Coherence, and Integration. Policy Sci. 2017, 50, 745–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.R. How Organizations Act Together: Interorganizational Coordination in Theory and Practice; Routledge: Oxon, MS, USA; New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 2-88449-173-2. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, B.G. Pursuing Horizontal Management: The Politics of Public Sector Coordination; Studies in government and public policy; University Press of Kansas: Lawrence, KS, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-7006-2093-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ferry, M. Pulling Things Together: Regional Policy Coordination Approaches and Drivers in Europe. Policy Soc. 2021, 40, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Canto classics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-107-56978-2. [Google Scholar]

- Berardo, R.; Turner, V.K.; Rice, S. Systemic Coordination and the Problem of Seasonal Harmful Algal Blooms in Lake Erie. Ecol. Soc. 2019, 24, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearborn, D.C.; Simon, H.A. Selective Perception: A Note on the Departmental Identifications of Executives. Sociometry 1958, 21, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, C.; Hurka, S.; Knill, C.; Peters, B.G.; Steinebach, Y. Introducing Vertical Policy Coordination to Comparative Policy Analysis: The Missing Link between Policy Production and Implementation. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 2019, 21, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, T.; De Francesco, F.; Maggetti, M.; Ruffing, E. Transnational Bureaucratic Politics: An Institutional Rivalry Perspective on Eu Network Governance. Public Adm. 2016, 94, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, T.; Danken, T. Institutional Logics in Inter-Departmental Coordination: Why Actors Agree on a Joint Policy Output. Public Adm. 2017, 95, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessisches Statistisches Landesamt. Bevölkerung in Hessen Am 31. Dezember 2023 Nach Landkreisen, Nationalität Und Geschlecht. Available online: https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/receive/HEHeft_mods_00013581 (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Bundesamt für Kartographie und Geodäsie. Verwaltungsgebiete 1:250 000 Stand 01.01. (VG250 01.01.); Bundesamt für Kartographie und Geodäsie: Frankfurt, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Vereinigung für Wasserwirtschaft, Abwasser und Abfall. Merkblatt DWA-M 550. Dezentrale Maßnahmen zur Hochwasserminderung; Deutsche Vereinigung für Wasserwirtschaft, Abwasser und Abfall: Hennef, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hessian Agency for Nature Conservation, Environment and Geology. Aktualisierte Starkregen-Hinweiskarte für Hessen; Hessian Agency for Nature Conservation, Environment and Geology: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- G., K. Nach Unwetter Überflutungen im Gesamten Stadtgebiet-Über 500 Feuerwehreinsätze. Freitags Anz. 2007, 78, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Helfferich, C. Leitfaden- und Experteninterviews. In Handbuch Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung; Baur, N., Blasius, J., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2022; pp. 875–892. ISBN 978-3-658-37984-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bogner, A.; Littig, B.; Menz, W. Interviews Mit Experten: Eine Praxisorientierte Einführung; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014; ISBN 978-3-531-19415-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ruge, K.; Ritgen, K. Local Self-Government and Administration. In Public Administration in Germany; Kuhlmann, S., Proeller, I., Schimanke, D., Ziekow, J., Eds.; Governance and Public Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 123–141. ISBN 978-3-030-53696-1. [Google Scholar]

- Köck, W. Zur Entwicklung des Rechts der Wasserversorgung und der Abwasserbeseitigung. In Die Governance der Wasserinfrastruktur. Nachhaltigkeitsinstitutionen zur Steuerung von Wasserinfrastruktursystemen; Gawel, E., Ed.; Duncker & Humblot: Berlin, Germany, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 63–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, M. Hochwasserschutz (§ 72–§ 81). In Wasserhaushaltsgesetz, Abwasserabgabengesetz; Sieder, F., Zeitler, H., Dahme, H., Gößl, T., Rossi, M., Knopp, G.-M., Lorenzmeier, S., Müller, J., Schenk, R., Schwendner, J., et al., Eds.; Beck-online Bücher; C.H. Beck: München, Germany, 2024; ISBN 978-3-406-38892-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hessisches Landesamt für Naturschutz, Umwelt und Geologie. Hochwasserrisikomanagement (HWRM) in Hessen-3. Zyklus. Available online: https://www.hlnug.de/themen/wasser/hochwasser/hochwasserrisikomanagement (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Sachsinger, P.; Schrödter, W. Hochwasserschutz und Städtebaurecht. Z. Für Dtsch. Int. Bau Vergaber. 2015, 38, 534–541. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, J. Hochwasserschutz in Raumordnung und Bauleitplanung–Was ist zu tun? Z. Für Umweltr. 2023, 34, 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Völker, V.; Jolk, A.-K.; Willen, L.; Illgen, M. Kommunale Überflutungsvorsorge–Planer Im Dialog; Spree Druck Berlin GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dreßler, U. Kommunalpolitik in Hessen. In Kommunalpolitik in den Deutschen Ländern; Kost, A., Wehling, H.-G., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010; pp. 165–186. ISBN 978-3-531-17007-7. [Google Scholar]

- Heinelt, H.; Hlepas, N.-K. Typologies of Local Government Systems. In The European Mayor; Bäck, H., Heinelt, H., Magnier, A., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2006; pp. 21–42. ISBN 978-3-531-14574-7. [Google Scholar]

- Egner, B. Directly Elected Mayors in Germany: Leadership and Institutional Context. In Directly Elected Mayors in Urban Governance; Sweeting, D., Ed.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2017; pp. 159–178. ISBN 978-1-4473-2704-2. [Google Scholar]

- Henneke, H.-G.; Ritgen, K. Kommunalpolitik und Kommunalverwaltung in Deutschland; C.H. Beck: München, Germany, 2021; ISBN 978-3-406-72931-7. [Google Scholar]

- Tellenbröker, J. Die Feuerwehren im System der Gefahrenabwehr–Eine Aufgabenbeschreibung. Z. Für Gesamte Sicherheitsrecht 2022, 5, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Vereinigung für Wasserwirtschaft, Abwasser und Abfall. Risikomanagement in der Kommunalen Überflutungsvorsorge für Entwässerungssysteme bei Starkregen; DWA-Regelwerk. Merkblatt; DWA: Hennef, Germany, 2016; ISBN 978-3-88721-392-3. [Google Scholar]

- Stadtplanungs- und -bauamt Mörfelden-Walldorf. Sachbericht Zum Prüfantrag Der GRÜNE-Fraktion Und Der CDU-Fraktion Vom 14.11.2022. Umsetzung Schwammstadt-Konzept; Stadtplanungs- und -bauamt Mörfelden-Walldorf: Morfelden-Walldorf, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Public Order Office Mörfelden-Walldorf. Bericht zur Örtlichen Gefahrenabwehr; Municipal Board, Public Order Office Mörfelden-Walldorf: Mörfelden-Walldorf, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, K.; Bruch, N.; Meyer, M.; Schönefeld, J. Die Verbreitung Kommunaler Klimaanpassungspolitik in Hessen: Bestandsaufnahme und Perspektiven; Institut für Wohnen und Umwelt: Darmstadt, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.; Labadz, J.C.; Smith, A.; Islam, M.M. Barriers to the Uptake and Implementation of Natural Flood Management: A Social-ecological Analysis. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2020, 13, e12561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.; Penning-Rowsell, E.C. Micro-political and Related Barriers to Stakeholder Engagement in Flood Risk Management. Geogr. J. 2012, 178, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawxwell, T.; Mok, S.; Maciulyte, E.; Sautter, J.; Theobald, J.A.; Dobrokhotova, E.; Suska, P. Municipal Governance Guidelines; Fraunhofer Institute for Industrial Engineering, University of Stuttgart: Stuttgart, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- StädteRegion Aachen. Aufbau eines Risikomanagements für Hochwasser- und Starkregenereignisse (“Regionales Hochwasserrisikomanagement”); Koordinator/in Hochwasser für die StädteRegion Aachen; StädteRegion Aachen: Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Name | Date | Description and Relation to Flood Management |

|---|---|---|

| Drainage Ordinance | 01/1999 | Regulates the use of the sewer system. Introduces water discharge fees for properties based on area size. Incentives rainwater infiltration, surface unsealing, green roofs, and rainwater harvesting by property owners. |

| General Drainage Plan | 02/2012 | Wastewater and stormwater management concept for the urban catchment area. Based on hydrodynamic modeling and load calculations, it defines measures for expansion and reinforcement of the sewer system. |

| Climate Protection Master Plan | 12/2021 | Strategic framework for climate protection adopted by the municipal council. Calls the administration to formulate action plans in key areas such as climate adaptation, including creation of water infiltration facilities, unsealing measures and the maintenance of urban green spaces. |

| General Disaster Management Concept | 09/2022 | Comprehensive framework for disaster preparedness and response. Establishes a crisis response unit, structures emergency communication, and ensures the continuity of critical services during floods and other emergencies. |

| Inner Development Concept | 10/2022 | Short- to medium-term land-use planning framework. Flood protection was a key consideration in site selection, excluding areas near water bodies or involving the reduction of inner-city green corridors. |

| Stadtgrün statt Graustadt | 10/2022 | Funding program supporting voluntary urban greening. Eligible measures regarding rainwater retention are, e.g., green roofs, facades, and the unsealing and greening of paved front yards. Contributes to flood prevention through increased surface permeability. |

| Integrated Urban Development Concept (MöWa2o3o) | in prep. | Long-term urban development strategy that addresses the risks of heavy rainfall and flooding. It aims to guide municipal development plans and construction projects, incorporating the assessment of risk areas for both fluvial and pluvial flooding in city planning. |

| Concept/Instrument | Responsible Unit | Level | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Protection Master Plan | Environment | 1–2 | Lead organization |

| Inner Development Concept | City planning | 1–2 | Lead organization |

| Integrated Urban Development Concept (MöWa2o3o) | City planning | 1–2 | Lead organization |

| General Disaster Management Concept | Fire brigade | 4 | Inter-organizational group |

| General Drainage Plan | Stadtwerke | 1 | Lead organization |

| Drainage Ordinance | Stadtwerke | 1 | Lead organization |

| Stadtgrün statt Graustadt | Environment | 1–2 | Lead organization |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Boer, W.; Flath, L.; Knodt, M.; Schmalz, B. From Silos to Synergy: Improving Coordination in Local Flood Management. Water 2025, 17, 2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17152212

de Boer W, Flath L, Knodt M, Schmalz B. From Silos to Synergy: Improving Coordination in Local Flood Management. Water. 2025; 17(15):2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17152212

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Boer, Wibke, Lucas Flath, Michèle Knodt, and Britta Schmalz. 2025. "From Silos to Synergy: Improving Coordination in Local Flood Management" Water 17, no. 15: 2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17152212

APA Stylede Boer, W., Flath, L., Knodt, M., & Schmalz, B. (2025). From Silos to Synergy: Improving Coordination in Local Flood Management. Water, 17(15), 2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17152212