1. Introduction

Spain’s Insurance Compensation Consortium (Consorcio de Compensación de Seguros, CCS) was founded in 1954 and is the state-owned insurance company that covers claims caused by extraordinary events such as Storm Filomena or, more recently, the eruption of the volcano on La Palma in 2021. Since then, the CCS has been closely linked to the coverage of extraordinary risks, as the central figure in a compensation system for catastrophic damages. In addition, since the beginning of 1998, its activity has also included the field of environmental risks, as part of the Spanish Pool of Environmental Risks. Finally, with the passing of Law 44/2002 of 22 November, the CCS assumed the functions of liquidation of insurance entities that the CLEA (Insurance Entities Liquidation Commission) had been carrying out.

Its capital, independent from that of the State, is financed with the premiums and surcharges paid by the insured. The CCS also benefits from the State guarantee, although in practice this has never been necessary [

1]. In Spain, there is an “unlimited government guarantee” for catastrophes. The CCS is responsible for the coverage of certain risks of natural phenomena and some social events. The specific features of such events mean that historically they have not been able to be covered by the private sector due to non-compliance with certain actuarial requirements. The coverage for these risks appears as an add-on to property damage products, which are themselves optional [

2].

The CCS is financed with the income from the surcharges that are applied to most insurance policies. As such, it is as if each insured had two insurance policies in one: one for ordinary risks contracted with their preferred insurance company, and another with the CCS. However, not everyone takes out private insurance. In Spain, the insurance penetration rate is 75% [

1], meaning the rate is the same for the coverage of extraordinary risks.

The objective of the CCS in the field of catastrophic risks is to indemnify claims arising from extraordinary events occurring in Spain and causing damage to persons and property located in Spanish territory. This is done on a compensation basis through a policy taken out with any private entity in the market. These elements represent the solidarity (compensation) and preventive nature (insurance policy taken out) that should be the basis of any risk management system. However, it does not consider a third pillar underpinning this management; namely, the responsible behavior of those facing the risk.

This approach by the CCS is consistent with the risk management approach for uninsurable risks. It has been claimed [

3] that natural catastrophes are extremely difficult to insure. In recent years, however, a new view on the insurability of natural catastrophes is gaining momentum, in light of which the same author [

4] states that “

The experience accumulated over the past decades has made it possible to transform poorly known hazards, long considered uninsurable, into risks that can be assessed with same precision. They exemplify however the limits of the risk-based premium method, as it might imply unaffordability for some”.

Comparative research on flood insurance systems reveals a wide diversity of institutional arrangements across countries. France operates a mixed system in which private insurers provide coverage backed by a public reinsurance scheme through the Caisse Centrale de Réassurance [

5]. In Germany, flood insurance is voluntary and offered by private companies, but penetration rates remain low due to limited risk awareness and affordability challenges [

6]. In the United Kingdom, the recently implemented Flood Re scheme combines public oversight with private provision to ensure the affordability of premiums for high-risk households, particularly in light of increasing flood risks [

7]. The United States manages flood risk primarily through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), a federally administered system facing chronic financial deficits and repeated calls for reform [

8]. The Netherlands presents a unique case, where private insurance against flood damage is virtually nonexistent, and flood risk is treated as a public responsibility managed through structural mitigation and state intervention [

9]. These diverse models reflect varying national approaches to risk-sharing, insurance affordability, and state intervention. Against this backdrop, the Spanish model exhibits distinctive institutional and financial characteristics that merit closer examination.

Given this situation, we believe that it may be time to start rethinking the system of coverage. Solidarity, so far the only way to deal with such events, raises moral hazard issues that could perhaps be addressed through risk-based premium methods. By applying the alternative proposed in this paper, responsible behavior can be rewarded, and the effectiveness and efficiency of covering this type of risk would lead to a fairer and more sustainable system for society as a whole.

Under the proposed model, insured parties would have stronger incentives to implement preventive measures aimed at reducing flood-related losses, as these would no longer be fully covered by the CCS. Regarding moral hazard, if policyholders are aware that the CCS will only compensate for severe (catastrophic) events, they may be more inclined to adopt risk-reducing strategies. This is because, under the current system, the perceived need for prevention diminishes when all flood-related claims are covered by the CCS and the premium is not adjusted for risk.

The premium collected by the CCS is calculated as a fixed percentage of the premium paid for general property risk coverage provided by private insurers. Since the CCS is a public entity, policyholders may perceive it as offering low-cost coverage, further reducing their perception of the actual cost of flood risk and undermining preventive behavior.

In contrast, under the proposed framework, if private insurers were responsible for covering minor flood-related damages, they would have a stronger economic incentive to require or promote preventive measures among policyholders. This could lead to a reduction in both the frequency and severity of small losses and, consequently, the cost of premiums associated with this layer of risk. As noted by [

4], this system would represent an intermediate model between the current Spanish coverage scheme and the German system.

There are two important issues to consider when it comes to catastrophic risk coverage: moral hazard and adverse selection. The first refers to the agents’ attitude towards the risk once they know that the economic consequences of the risk are covered. The second refers to how the different information available to policyholders about the actual risk to which they are exposed influences their decision to cover it. In other words, these two issues are closely related to the responsible behavior of agents.

In relation to risk, natural catastrophes are characterized by their low frequency (occurrence) and high intensity (volume of losses), with a large number of highly correlated losses concentrated in a short period of time, which requires tailored insurance solutions. These solutions must ensure sufficient financial capacity and efficient claims management. This specific characteristic of catastrophic risk may make it necessary to consider aspects of solidarity beyond the mutuality that underlies actuarial operations, with the aim of preventing adverse selection. For this reason, compulsory adherence to the coverage system is an essential element in catastrophic risk coverage methods.

Natural catastrophes are phenomena that can cause great material and human damage, with the degree of harm depending on a series of factors. Some factors cannot be controlled, such as the duration, the intensity, and the frequency, among others. However, there are other factors that can be controlled by adopting measures to help prevent major damage and to minimize its impact. The latter factors represent the responsible behavior of the actors affected by the risk. In terms of moral hazard, agents’ behavior may change when the premiums are not risk-based.

The adverse selection literature is very applicable here and is supported by many empirical studies [

10]. However, several authors recognize that adverse selection theories may not be suited to the analysis of natural catastrophe insurance. The adverse selection problem relates to information about the risks. There are two elements to consider in the basis of insurance: the risk and the group exposed to the risk. For insurance to work properly, all those potentially affected must be insured and not just the goods or people most exposed to extreme risk. Thus, the risk is shared among all those potentially affected, diversifying the risk by compensating higher-risk portfolios with others with less exposure to risk. In this way, the probability of having to face the problem of anti-selection or adverse selection is reduced. In such situations, information asymmetry could work both ways [

11]: potentially affected people could either overestimate or underestimate their true probability of loss [

12,

13,

14,

15], while insurance companies have better access to information through predicting and risk-spreading techniques to rate the catastrophe exposures.

In the case of floods in Spain, as with other catastrophic phenomena, this problem is addressed through the application of a compulsory surcharge in all insurance policies taken out by individuals (both home and vehicle). This surcharge, which is intended for catastrophe risk coverage, is a percentage of the insured value, not of the premium. The obligation to extend catastrophe insurance to all insured parties significantly reduces adverse selection. Given that the areas of highest exposure to one event do not necessarily coincide with those of highest exposure to the other, this measure increases efficiency when it addresses more than one risk (for example, flood and earthquake), meaning they can compensate one another and make risk distribution more effective [

8]. However, this could be considered more of a tax than a premium for the coverage of catastrophic risks, since it does not take into consideration the exposure to the risk. The mandatory nature of this surcharge, as indicated in the following paragraph, is yet another reason why it should be considered a tax.

Thus, the CCS is currently financed by compulsory surcharges on premiums for certain lines of property (urban, vehicle) and personal insurance, collected by private companies. Compulsory insurance is levied with rates (surcharges) that do not reflect the level of risk in a given locality, which reduces the potential capacity of insurance as an incentive to reduce risk. If geographical areas of higher flood risk were taken into account, the rates applied to these surcharges should be adjusted so that the insured parties pay more in areas where the costs of flooding are higher. This could also aggravate moral hazard, since the mere fact of being policyholders could make them become less proactive in reducing their exposure and vulnerability to risk.

The current Spanish flood insurance model assigns coverage for all flood-related damages—regardless of severity—to the public sector through the Consorcio de Compensación de Seguros (CCS). While this centralized approach ensures universal protection, it overlooks the potential for a more efficient and actuarially sound distribution of responsibilities. We propose a differentiated system in which non-catastrophic flood losses, typically localized and statistically more predictable, would be covered by private insurance policies, priced according to risk-based criteria and mutualization principles. In contrast, catastrophic or extreme flood events, which present systemic challenges and exceed private sector capacity, should remain under the purview of the CCS, funded through mechanisms of general solidarity such as taxes or mandatory levies. This public–private balance would incentivize risk reduction, reinforce the role of insurance as a risk management tool, and safeguard the long-term sustainability of the system. Similar hybrid models have been adopted in other countries, such as Flood Re in the UK and the French system involving the Caisse Centrale de Réassurance, providing relevant points of comparison.

The objective of our work is twofold. First, by relying on the available data on claims covered by the CCS, we attempt to show that flood risk has specific characteristics that allow it to be managed more efficiently. Without overlooking the solidarity needed to appropriately deal with this type of risk, in its catastrophic or extreme version, the availability of more and better data should help us to improve the system to more accurately reflect the relationship between premium and risk. Several studies show the possibility of an effective treatment of the information available on floods with a view to improving the risk management of this type of claim [

4,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Second, we propose a two-level system for flood risk. The first level would include flood losses that cannot be classified as catastrophic, since they affect isolated assets that are not correlated with each other. At this level, coverage should be provided through a risk-based premium system. The second level would deal with flood losses that can be classified as extreme or catastrophic flood events, given their characteristics of a high concentration of losses under the same event, and these would be covered by a solidarity-based system.

In this way, since the owners of the properties most exposed to the first level of flood risk will have to pay higher premiums for their coverage, they will be incentivized to take measures to reduce the economic consequences of the loss. By doing so, they can reduce the amount of premiums they will ultimately have to pay. Meanwhile, the extraordinary risk coverage system would maintain its solidarity function in those cases in which, due to the specific characteristics of flooding, it is impossible to insure the property exposed to this type of event.

The advantages of this system would lie in improving the information provided to policyholders, through the risk-based premium, about the real risk they are assuming. We believe this will raise awareness of the need to take preventive measures, as well as enable the establishment of a fairer system for the distribution of the cost of claims. At the same time, it makes it possible to establish a system of solidarity coverage for those natural events which, due to their inherent characteristics, would be impossible to cover through private systems, either because of the consequences that this could have for the solvency of the insurance sector, or because it would imply a premium amount that would totally discourage potential policyholders.

As for the disadvantages that the implementation of a risk-based premium system could entail, it is worth noting a very significant increase in the cost of flood insurance. This would most likely lead to problems of adverse selection and underinsurance, while limiting the solidarity benefits of the current model with respect to other natural catastrophe risks. This is the reason for establishing a first layer to cover those natural events that generate flood losses but have little aggregate economic impact. These events could be effectively managed by the private insurance sector, given their low impact on the stability and solvency of the sector. The second level would continue to be managed by the CCS, in the same way as it has done so far, with the objective of covering events classified as extraordinary, given the high volume of losses they generate.

We believe that our model applies the principle of solidarity together with that of actuarial fairness. The extreme natural event, including high-severity flood events, would be covered by the CCS similarly to how it is done at present. On the other hand, occasional flood events not considered extraordinary would be covered by the private sector. This differentiation would encourage the adoption of precautionary measures to reduce the consequent costs of flooding, especially in the case of non-catastrophic events.

At the same time, we consider it appropriate to create a financing policy for the responsible authorities that provides them with more resources to carry out forecasting and warning measures that reduce the damage caused by extreme floods. In Spain, this work is currently entrusted to the river basin authorities [

20]. It should be borne in mind that flood prevention measures are essential to alleviate the economic cost caused by these events. If it were possible to change the coverage policy provided by the CCS (our first proposal of the two-level system), so that it covers only extraordinary floods, the CCS could allocate part of its resources and provisions to the river basin authorities to finance preventive measures that reduce the cost caused by floods. This action by the CCS could mean a future increase in flood prevention measures as part of the Flood Risk Management Plan for 2021–2027. The management plan aims to achieve coordinated action by all public administrations and society to reduce the negative consequences of floods, focusing on the program of measures that each public administration must apply within the scope of its powers to achieve the intended target.

The objectives proposed in this document are intended to emphasize the qualitative aspects over the quantitative aspects of the flood loss coverage model. We are aware of the need to further explore the methods to be used to evaluate these risks in order to achieve a fair and sustainable pricing system. There is also a need to determine the point at which the aggregate loss generated by a single event is sufficiently high to be classified as an extreme or catastrophic loss.

In the next section, we discuss flooding as an extraordinary risk under the CCS framework, detailing what is meant by extraordinary risk as well as flood risk by analyzing the database.

Section 3 describes the flood risk coverage system offered by the CCS.

Section 4 presents the discussion and conclusions drawn.

2. Flooding as an Extraordinary Risk Under the CCS Framework

An exhaustive list of the natural events that are covered by the CCS is provided in Royal Decree 300/2004 of 20 February on extraordinary risk insurance. Among the events for which the CCS is responsible, the most common are floods, sea storms, cyclonic storms, tornadoes, and earthquakes (The CCS also includes among the risks covered those related to human-related actions, such as acts of terrorism, rebellion, and actions of the Armed Forces and Security Forces in peace times, in addition to other types of actions related to the solvency and stability of the insurance sector in Spain. Readers can find a broad overview of CCS actions on its website (

https://www.consorseguros.es/ambitos-de-actividad/seguros-de-riesgos-extraordinarios/funcion-y-objetivo, accessed on 25 June 2025). For specific information on extreme events covered by the CCS, we recommend the following document [

2]).

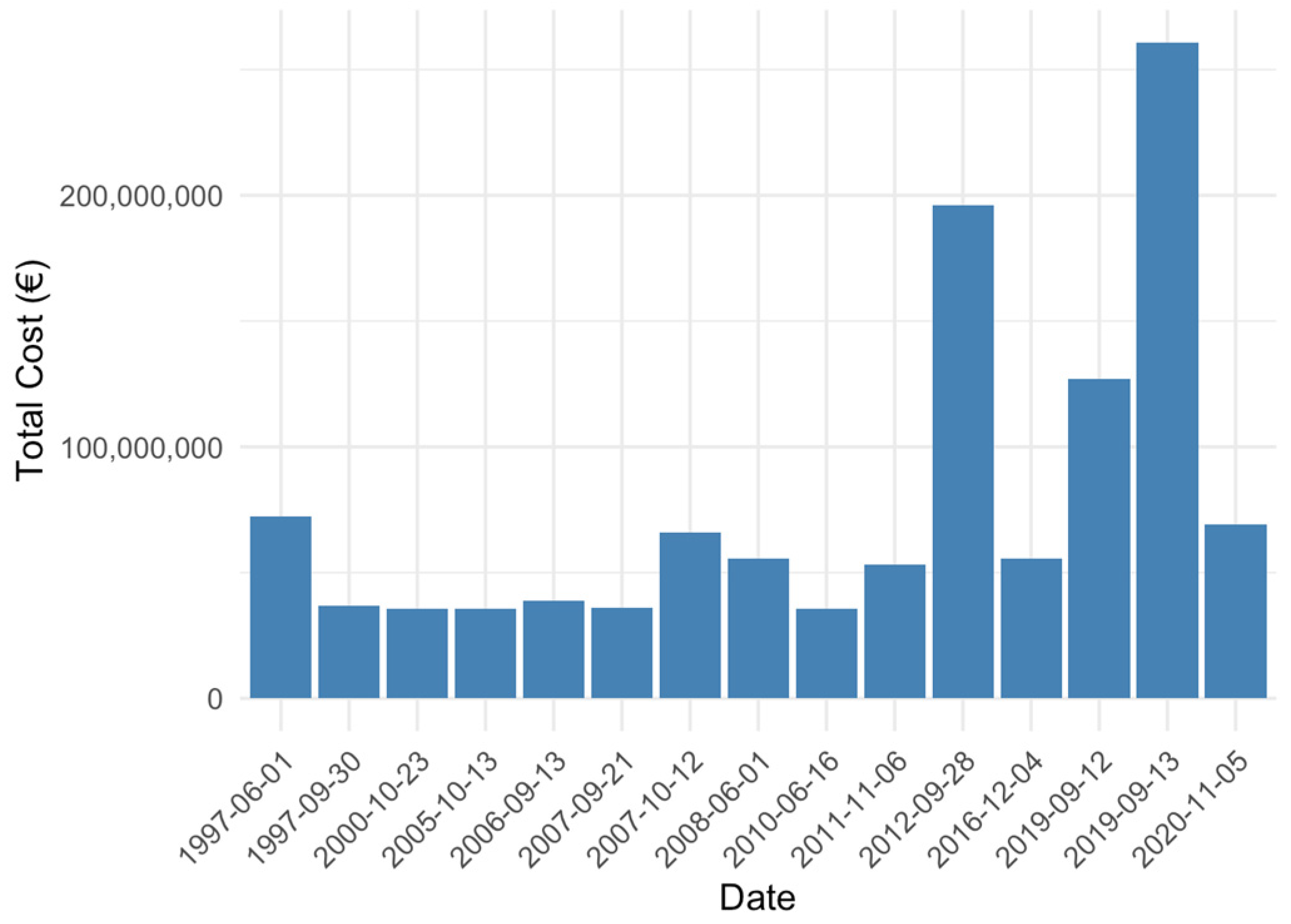

The aim of

Figure 1 and

Table 1 is to show the relative importance of floods among the natural catastrophic events covered by the CCS, both in terms of the number of claims they generate and the compensation paid in current euros. From the available data (The data used in this work were provided by the CCS. We have at our disposal a database with a total of 1,419,036 claims that occurred in Spain between 1 January 1996 and 31 December 2020, related to floods, earthquakes, storms, and sea storms), it is clear that floods account for a large proportion of the claims covered by the CCS.

Figure 2 shows that, over the period 1996–2020, more than two-thirds of the cost borne corresponds to flood claims, and 45.9% of the total claims are covered by the CCS.

As

Table 1 shows, floods and storms are the main natural events covered by the CCS, although floods are clearly the most important in monetary terms.

2.1. What Is Meant by Extraordinary Risks?

Before delving into the issue that concerns us, it is worth clarifying what is meant by extraordinary risks.

It is understood that extraordinary risks refer to events that are statistically rare and whose magnitude and/or effects exceed those of a normal risk, for example, in the case of floods or earthquakes, or as a result of political or social turbulence. In general, this type of risk is not covered by insurance companies.

From an actuarial perspective, the definition of extreme events is based on the following expression [

21]:

While the actuarial literature offers a wide array of technical criteria and statistical tools for identifying extreme events—such as the generalized extreme value (GEV) distribution or peaks over threshold (POT) models—this paper does not aim to determine a formal threshold at which flood-related losses should be classified as catastrophic. Instead, we adopt a general conceptualization of extreme events, as proposed by [

21], to support a practical framework for policy reform. According to this perspective, extreme events are characterized by their disproportionate influence on total losses, as a small number of days account for a very high share of aggregate compensation. This conceptual approach aligns with our empirical analysis of CCS data, which shows that a handful of events concentrate most of the compensation payouts. Therefore, the distinction we propose—between ordinary and extraordinary flood events—is operational rather than statistical, and serves as a basis for designing a more efficient and balanced public–private flood insurance model. Other definitions of catastrophic risks or extreme events can be found in [

22,

23,

24].

Other authors [

4,

25] model extreme events based on the concept of correlation between losses generated by the same natural catastrophe. For these authors, extreme losses are related to the impact of the event on a high percentage of the exposed population. In this situation, the authors show how a macro-coverage system ensures the financial sustainability of the insurance sector. However, it does not always guarantee efficient risk management.

In line with the concept of the extreme event, we will consider the daily cost as a measure of the aggregate flood loss caused by a catastrophic or common event, which has had to be covered by the CCS. Some limitations of this type of metric, related to events that may last more than one day, will be discussed below. Catastrophic events lasting more than one day are infrequent, but their salience facilitates their identification and treatment.

In addition, the geographic location and size of cities will also be key factors in determining whether the aggregate loss has been caused by the same event; the correlation between claims is closely related to the proximity between insured assets. Since the objective of this paper is to present the outline of a new system of coverage for extraordinary or catastrophic flood risk, we do not consider it necessary to go into this kind of detail in this paper. Therefore, in the authors’ opinion, its existence does not distort the results obtained from the analysis.

As can be seen from the available data, there is a large number of days with a very low number of claims. As an example, out of the total of 9131 days analyzed, claims are recorded in a home or homeowners’ association in Spain on 6325 days, and on 5419 (85%) of those days, the number of claims is less than or equal to 50. Considering the entire national territory, the authors do not consider that a day with 50 claims can be considered as an extreme event (In this case, as indicated above, geographical aspects are not accounted for. If the losses occurred in the same geographical area, it could be considered an extraordinary event) which cannot be covered through a private insurance system involving risk-based premiums. In addition, the aggregate payout for days with less than 50 claims represents 8% of the total payout over the 25 years.

2.2. Flood Risk

As mentioned above, one of the questions we ask in this study is whether the action of the CCS in the face of flood risk corresponds to the coverage of extraordinary events or merely to the coverage of any loss resulting from the occurrence of a flood caused by natural events; rain, overflowing rivers, lakes, etc. In view of the available data, only a part of the flood losses covered by the CCS correspond to extreme events and are, therefore, uninsurable. The characteristics of the other flood losses covered by the system allow them to be treated as insurable risks, given their probability of occurrence and their economic consequences.

The distinction between one type of coverage or another, as we show in the following sections, will determine whether the main objective of the action should be restitution for the loss caused by the flood, that is, compensatory in nature, or whether the prior prevention and management of risk should be considered the primary objective, together with compensation.

From the data in

Table 2, in a period of 9131 days, from January 1996 to December 2020, we can see the breakdown of the claims covered by the CSS:

Low: 31.06% of the days have an incident rate with a daily cost of less than 0.5 million euros.

Medium: 1.3% of the days account for a daily cost of between 0.5 and 20 million euros.

Extreme: Eight days have a cost of above 20 million euros per day. Of these, the 12 and 13 September 2019 DANA event (DANA stands for Depresión Aislada en Niveles Altos (Closed Upper-Level Low). The DANA phenomenon, traditionally called the “cold drop”, gives rise to rain and intense storms. Thus, the entry of a mass of cold air into the core of the atmosphere that comes into contact with warmer air near the ground generates instability, which favors the formation of clouds that cause heavy storms. In addition, this event should be considered in cases where the duration of the event is longer than one day) should be highlighted, as they are related to a single natural event and should, therefore, be considered together as a single event. In other words, a single flood event generates a daily cost of more than 320 million euros over a total period of 25 years.

Determining whether a flood event is an extreme event is highly subjective. A loss may be deemed extraordinary for exceeding a minimum number of claims or for exceeding a minimum cost in damages to be covered due to the event in question. Under the current regime, a flood event caused by rainfall is covered in the same way regardless of whether it has been exceptional in nature, given its intensity (extreme event), or of a habitual nature. It is not the aim of this paper to establish the criteria for determining when an event is extreme or catastrophic. As we have indicated, this paper seeks to propose a generic framework for an efficient system for dealing with flood risk. One of the effects of climate change is clearly an increase in torrential rainfall events that will need to be dealt with efficiently and effectively, especially from a risk management point of view.

As an illustrative example, as we show in

Figure 3, we classified low-loss days as those falling below the 90th percentile, medium-loss days as those between the 90th and 99th percentiles, and extreme-loss days as those exceeding the 99th percentile. However, it is important to note—as emphasized in the conclusions—that this categorization is intended for analytical purposes only and does not constitute a definitive risk threshold.

As noted above, the limit for characterizing a loss event as extreme can be based on criteria such as exceeding a minimum number of claims or exceeding a minimum cost in the damage to be covered due to the event. In the current system, a flood (Flood that meets the criteria defined by the CCS to be part of the loss event for this coverage) is covered in the same way, regardless of whether it has been exceptional in nature, given its intensity (extreme event), or of a habitual nature.

Figure 2 shows the days, in the period 1996–2020, when the CCS had to face a cost greater than 35 million euros per day for flood events.

As stated above, from all the historical series available, we only find three days of flood events that account for accumulated compensation of over 50 million euros. And one single event, the DANA that affected the south of Alicante and the north of Murcia in September 2019, entailed a cost of over 300 million euros for the CCS. That is, a cost 5.2 times higher than that of the next highest cost event in the series.

In

Table 3, we clearly see the effect on the total cost of the extreme events. This table represents the cumulative relationship between the number of days since the claim occurrence and the total accumulated cost, as well as the cumulative percentage of claims.

A single extreme weather event, the DANA of September 2019, accounts for 35.28% of the total cost assumed by the CCS for flooding. Similarly, 50% of the total loss due to flooding is generated by the 5 days with the highest loss, and 75% of the incident rate is generated on one day for each year of the historical series.

To better understand the effect of an extraordinary event, it is important to show the incident rate around the event date.

Table 4 shows the concentration or the correlation effect to determine the extreme nature of the event.

It can be concluded that, taking the daily claim rate as the unit of measurement, it is easy to divide the claims into two large groups: on the one hand, those days with a sufficiently regular occurrence and an acceptable cost, while in the other group there are those claims which, due to their very low frequency but very high cost, can be considered extreme. The inclusion of other aspects, especially geographical ones, will allow a more precise distinction between extreme and non-extreme claims.

As we have explained before,

Table 3 indicates that a large proportion of the total cost and claims are concentrated within a short period following the occurrence of the event (over 35% within 2 days and nearly 50% within 5 days). This is consistent with

Table 4, where specific days show a high number of claims and elevated costs—particularly on 12 and 13 September—likely reflecting the materialization of damages and the initiation of the claims process.

As observed in

Table 4, 13 September, with the highest number of claims and associated costs, may represent one of the “key” days driving the rapid accumulation seen in

Table 3. This suggests that discrete events with high frequency and intensity significantly impact the total cost and initial claims burden. It also indicates that risk is not evenly distributed over time but rather concentrated in specific moments characterized by extreme adverse conditions.

Based on this, it can be concluded that since a large share of claims is concentrated in brief, severe events, the implementation of preventive measures and rapid response during these periods is critical to mitigating damages and costs.

3. Flood Risk Coverage

As indicated above, when it comes to claims stemming from natural catastrophes, the function of the CCS is to compensate for the economic consequences by covering direct losses such as replacement and repair costs. To this end, the Spanish system of coverage for extraordinary risks is based on two basic principles:

The principle of compensation, which includes compensation between risks (all risks covered are given the same consideration and treatment), geographical compensation (all areas of the country are given the same consideration and treatment, regardless of the type of risk to which they are most exposed), and temporal compensation (extended periods of time should be considered, in which years of low or moderate loss allow the accumulation of resources to address peak years of high loss).

The principle of collaboration with the Spanish insurance market in the management of the system. Extreme risk coverage is provided through private insurance contracts that individuals take out individually and freely with private insurance companies. The premium paid by the insured also includes a surcharge that goes to the CCS, which is indicated separately on the invoice, and private companies are responsible for its collection and subsequent transfer to the CCS. In the event of a claim, the insured passes the claim on to their insurance company, which passes it on to the CCS.

The risks included in the Spanish system of coverage for extraordinary risks are legally defined, based not on their quantitative characteristic (amount of damage caused) or their geographical effect (extension of the affected area), but on their qualitative characteristic, that is, considering the nature of the events that generate the loss. This means that the CCS indemnifies any type of flooding if it falls within the definition given by the CCS for this type of loss, regardless of whether the event that has generated the loss can be considered an extreme event. This means that there are many situations where the covered loss shows a sufficient lack of correlation for a risk-based premium system to be efficiently and effectively applied. For example, the official declaration of a catastrophe or disaster area is not necessary to initiate the compensation procedure. This shows that the correlation that characterizes extraordinary events is not a necessary condition for the flood cover offered by the CCS.

The high frequency and low intensity observed in the data on flood insurance provided by the CCS would justify the exclusion of some of these claims from coverage, since they are not extraordinary events. They can be efficiently treated by the insurance system based on risk premiums, with the advantages that this implies, and which will be analyzed later on.

Thus, we can conclude that the coverage system offered by the CCS goes beyond what we have defined as extraordinary risks. It is, in fact, a system of cover for risks associated with natural events, regardless of the degree and intensity of their impact.

This coverage system has proven to be effective over the years. The compensation objective has always been achieved, and the application of the guarantee system offered by the State has not been necessary at times of maximum or extreme severity, thus demonstrating the financial solvency of the system. However, the limited or non-existent relationship between the surcharge for extreme events and the exposure to this type of risk of the assets covered means that we cannot consider this system an insurance system. What we have is a compensation system based on solidarity, in fact, more like a tax system for the coverage of claims generated by extraordinary or catastrophic events.

Thus, the system maintained by the CCS does not account for the fact that the scope of the insurance activity goes far beyond indemnification. Insurance operations, and more specifically the premium to be paid by the insured, can be seen as a measure of the risk borne by the assets that are the object of the insurance contract, such that assets exposed to a higher degree of risk require a higher premium to be paid. Thus, by providing an explicit measure of the risk borne by the insured, the business of insurance directly influences the implementation of effective risk management.

Risk mitigation is the process of developing options and actions that, when implemented, will reduce the probability of the occurrence of a particular event or minimize its negative impact. This means that risk still exists, and we are still exposed to it, but in a controlled scenario and under conditions that allow us to reduce our exposure and allay the negative impact.

Measures aimed at mitigating the harmful consequences and the probability of occurrence of an event are beneficial to the insurance companies and/or the insured parties themselves: the former because they will see a reduction in the amount of compensation they have to pay in the event of a claim, and the latter because they will see a reduction in the price to be paid for the cover. In some cases, the adoption of preventive measures will enable the insured to take out insurance on the property affected by the risk, since otherwise, given the possibility of the occurrence of the event and the economic consequences that it entails, no entity would be willing to provide the insurance service. Some measures that we propose are as follows:

Identify highly flood-prone areas and undertake actions to prevent construction in these areas.

Reduce flood coverage or increase the premium for construction in highly flood-prone areas to help minimize flood losses.

3.1. Financing of the Consortium’s Coverage

Article 13 of Royal Decree 300/2004 of 20 February 2004 establishes the rules relating to the surcharge rates for extraordinary risk insurance.

Pursuant to the aforementioned regulation, the coverage of extraordinary risks by the CCS is financed through the application of a compulsory surcharge in all insurance policies, regardless of whether the policy in question stipulates that those extraordinary risks are covered by the company that issued the ordinary policy, or the policy excludes such coverage (in which case the CCS would be responsible for the coverage). In other words, the CCS is not dependent on any public funding to meet its indemnity liabilities in relation to this cover.

The CCS surcharge is derived from the application of its own rate on the sums insured in the policies. This rate, which differs according to the type of property covered, is applied uniformly across the entire Spanish territory and for all types of risks included in the system, regardless of the degree of exposure of the property to extreme events.

As indicated above, the compulsory nature of the coverage and the corresponding surcharge derive from the principles of compensation and solidarity, without the application of which the natural anti-selection pressure of these risks would make the coverage unsustainable. Another reason for it being compulsory is the difficulty for the market to find an equilibrium price between supply and demand. The difference between the two is, in most cases, due to the fact that policyholders (demand) do not perceive the risk, but no less important is the fact that it is difficult for insurers (supply) to apply the general principles of insurance without affecting their solvency and financial stability [

26,

27].

At the other extreme, we can find solutions that base the coverage of such catastrophes entirely on the private sector. The argument in favor of these solutions is that they promote the implementation of risk reduction measures, which, from a risk management perspective, are proactive in nature, with implications for damage reduction in the event of an incident. Arguments against them include the increased costs observed in risk-based premium systems, together with the possibility that the occurrence of the event could lead to extreme claims situations that would significantly affect the solvency of the institutions or even necessitate state intervention to compensate for unaddressed claims [

28].

3.2. The Benefits of a Two-Level System

Our motivation for writing this paper was the direct relationship that the CCS establishes between flood risk and the risk from extraordinary or catastrophic events. In our opinion, not all flood risks have the characteristics that merit their treatment as catastrophic risks. Therefore, the aim of the paper is to rethink the flood risk coverage system, proposing a first approximation to a model that allows an improvement in the efficiency of risk management, especially by encouraging the agents involved in this type of event to adopt preventive attitudes.

There is no doubt that the CCS’s activity in the insurance field has been and continues to be very beneficial. However, in view of the results observed, we wonder whether it is efficient to cover moderate-frequency, low-cost flood events. The distinction made in the previous section between natural events of an extraordinary nature and those that we believe should not be treated as such may help to configure a system of public–private partnership flood coverage that goes beyond the arrangement that currently governs the coverage of this risk.

Natural catastrophe schemes usually maintain a hybrid position between public and private insurance. The greater or lesser weight of the public or private part tends to be determined by historical, cultural, or economic factors. The Spanish case is among those coverage schemes where the entire burden falls on a state-owned insurance company, the CCS. This model is based on solidarity, where premiums are independent of the level of risk to which each insured asset is exposed. At the other extreme are those models based solely on a market system. The Spanish model has proven to be highly effective in its objective of establishing an agile and effective system focused on the compensation of losses caused by such events. Risk prevention tasks, which are inherent to any risk management system, have largely been overlooked.

The system we propose, following the model presented by [

4], is based on taking advantage of the classification of flood events according to the number of claims they generate. This classification is aimed at ensuring one of the basic principles of insurance: namely, that there must be little or no correlation between risks. Otherwise, the stability and economic solvency of the insurer may be compromised in the event of a high accumulation of risks around the same loss.

Establishing a minimum number of flood losses associated with the same climatic event would allow events exceeding that number to be classified as extreme. In that case, the claims would be covered by the CCS, which would basically not have to modify its current financing and action structure. However, this would make it possible to reduce, to a certain extent, the amount of the surcharge to be applied for the coverage of extraordinary risks.

As indicated throughout this paper, the frequency of floods is sufficient for adequate statistical treatment, with at least one incident every three days. We can, therefore, conclude that two types of flood events can be clearly distinguished: on the one hand, those arising from normal natural phenomena; on the other hand, those that are exceptional in terms of their occurrence and their devastating economic effects on goods and people in the affected areas. The latter could be characterized as extreme and catastrophic natural events.

If the occurrences do not generate a claims rate above the established limit, cover will be provided by the insurance companies with which the insured has taken out the policy. The advantages of this insurance system are that it promotes risk prevention measures and helps ensure a more accurate perception of the risk assumed by the insured due to the risk/premium ratio. The system could be effectively implemented and would improve risk management and reduce the economic consequences of claims.

Insurance market activity will facilitate an actuarially fair pricing system, where assets more exposed to risk will have to bear a higher premium. This would imply a fair distribution of the cost of claims, without the occurrence of extreme events jeopardizing the solvency of the insurance industry, which could leave the resulting damage uncovered.

Solidarity, which is necessary in situations of great social concern, would be limited to those situations that cannot be dealt with efficiently by market mechanisms. When extreme events occur, the only way to restore the situation of those affected is through the disinterested collaboration of their fellow citizens. This solidarity will be more effective if it is provided in advance, based on the system currently used by the CCS.

This system of pre-event solidarity, in which it is compulsory to include coverage for extraordinary damage in insurance contracts, allows both very low-cost coverage and an immediate, effective, and efficient application of resources in the event of a claim. If solidarity is claimed after the event, as is often the case when acting through public aid in such situations, these resources tend to arrive later and are subject to necessary but complicated bureaucratic control systems. In addition, we should consider that this type of action may disincentivize taking out insurance or adopting preventive measures: the so-called charity risk [

29].

We should not rule out the possibility of the CCS undertaking some kind of action aimed at promoting the prevention of catastrophic risks. Once the CCS limits its scope of action to the coverage of extraordinary flood risks, it should start to implement a proactive policy aimed at mitigating claims. For example, it could promote certain local actions by local councils in areas that are most affected by flooding or provide financial support to river basins for the adoption of safety and water control measures in the event of major floods. These would be actions which, through the resources received by the CCS, could help mitigate the direct consequences of the extreme event for those affected, while at the same time reducing the associated costs to be paid by the CSS.

Since extreme floods could be considered the predominant natural catastrophe, as they have the highest loss rate, it could be interesting for the CCS to consider establishing a flood zoning system to estimate the risk. Such a system could establish different risk zones according to the probability of occurrence of the extreme flood event, which would help encourage preventive measures to reduce costs. Depending on the different zones, different types of surcharges would be applied, which, without significantly affecting the final surcharge price, would allow policyholders to be more aware of the risk they face.

In cases of non-extreme floods, the application of the risk-based premium will allow policyholders to be more aware of the risk they are exposed to. This will encourage preventive measures and even discourage construction in areas with a very high risk of flood losses.

This system aims to distribute risk more equitably across the population and, indirectly, to prevent insurance premiums from becoming prohibitively high for those living in more vulnerable areas. However, this objective may conflict with the need to adjust premiums according to geographical risk, which can result in significantly higher costs for policyholders in high-risk zones, such as flood-prone regions.

To address this, a more balanced risk-sharing mechanism is proposed, whereby part of the revenues generated from premiums in low-risk areas could be allocated to subsidize premiums in high-risk zones. This approach would help mitigate disparities in coverage access, ensuring that insurance remains affordable even in the most vulnerable regions, while still reflecting the underlying risk levels.

Another option would be to implement parametric insurance models, where the policyholder pays a premium based on predefined parameters, such as rainfall levels or water depth in specific areas. These models can offer a more flexible and equitable solution for high-risk regions, providing timely payouts without significantly increasing costs.

A key strategy in the implementation of this system is to reward policyholders who undertake significant preventive measures, such as installing drainage systems, elevating buildings, or developing flood-resilient infrastructure. Private insurers could offer lower premiums to individuals who implement such measures, while the public reinsurance entity (e.g., the Consorcio) could apply discounts or bonuses for those who demonstrate investment in risk reduction. Private insurers could also establish a certification program for properties that meet specific flood protection standards, signaling that a property has implemented high-quality prevention and mitigation strategies.

Prevention incentives at the first level should combine direct financial rewards (e.g., discounts, bonuses), certification of preventive measures, and continuous education. Private insurers could design tailored programs that reward policyholders for enhancing the resilience of their properties against flooding. This approach not only promotes proactive risk management but also contributes to a reduction in claims, potentially leading to lower overall premiums across the system in the long term.

4. Discussion

The objective of the CCS in the field of catastrophic risks is to indemnify claims arising from extraordinary events occurring in Spain and causing damage to persons and property located in Spanish territory. This is done under the compensation principle and on the basis of policies contracted with any private entity in the market.

There is no doubt that Spain, through the CCS, has a robust system for the coverage of damages caused by extraordinary natural catastrophes such as floods. The Spanish CCS coverage system is working properly. The question we ask is whether the CCS is carrying out its function efficiently; that is, whether the resources allocated for this purpose are used in the best possible way. Natural disasters cannot be avoided, but it is possible to undertake actions that reduce claims costs when they occur.

Not all flood losses caused by natural events should be considered extreme events; only those of low frequency and high aggregate economic cost. However, in an environment where climate change scenarios point to a higher frequency of extreme floods in the future, it is imperative to review the coverage model for such events. A system that goes beyond mere damage compensation is essential for optimal flood risk management.

It is important to establish an appropriate risk and pricing policy by the bodies in charge of carrying out actions that contribute to minimizing the consequences of floods. Finding a balance between global solidarity and individual responsibility can lead to more effective risk management and hedging systems. In solidarity-based systems, prevention measures take a back seat, which in many cases can lead to situations of moral hazard. Given that such solidarity systems are essential when it comes to catastrophic events, identifying when a flood event should be considered catastrophic will allow the advantages of this system to be applied in these cases. In turn, it will allow the establishment of measures based on the level of risk for non-catastrophic flooding situations.

One of the features of protection systems based on actuarial fairness and risk-based premiums is that they incentivize the application of measures to prevent the economic consequences of these events. These measures help mitigate the expected severity of the effects caused by flood events and, consequently, reduce the amount of the premium to be paid by the insured. The promotion of flood prevention measures is essential to relieve the disastrous personal, social, and economic consequences of these events.

Not all naturally caused flood events should be considered extreme events; low frequency and high aggregate economic cost are the main characteristics that determine the extraordinary character of a given event. From the analysis of the available data provided by the CCS, we can conclude that flood risk can be divided into two main groups: on the one hand, claims that occur frequently throughout the available historical series and can be treated as ordinary risks, where the private insurance sector can act efficiently and effectively on the basis of a risk pooling system; on the other hand, claims which, given the high loss ratio they generate, must be treated as extraordinary risk that can only be managed through social solidarity systems such as the one used by the CCS in Spain.

We believe that it may be time to start rethinking the system of coverage provided. Using the available data on claims covered by the CCS, we aim to show that flood risk has specific characteristics that allow it to be managed more efficiently. Without overlooking the solidarity necessary for the appropriate treatment of this type of risk, in its catastrophic or extreme version, the availability of more and better data should help us to improve the system to more accurately reflect the relationship between premium and risk. Several studies show the possibility of an effective treatment of the information available on floods with a view to improving the risk management of this type of claim.

We propose a two-level system for flood risk coverage. The first level would include flood losses that cannot be classified as catastrophic, since they affect isolated assets that are not correlated with each other. At this level, coverage should be provided through a risk-based premium system. The second level would deal with flood losses that can be classified as extreme or catastrophic flood events, given the characteristic of a high concentration of losses under the same event, and these would be covered by a solidarity-based system.

The coverage system established through the CCS is undoubtedly an effective system of compensation for the economic consequences of catastrophic events, and it has proven to be an optimal instrument for the management of this type of catastrophe. The principle of solidarity has been shown to be essential for the achievement of effective coverage for those affected. When this cover is left solely to private insurance systems, the risk of insolvency that it implies for the insurance sector jeopardizes the coverage of the claims generated by this type of event.

However, if all flood claims are covered by a solidarity system, the insured could be affected by moral hazard and find no incentives to take preventive actions against floods. Thus, a two-level system, such as the one proposed, will make it possible to take advantage of coverage systems based on actuarial fairness in the case of non-extraordinary flood risk, together with the advantages of solidarity-based systems for the risk of flooding as a consequence of a catastrophic event.

The proposed two-level system would encourage users to exercise foresight to reduce costs. In addition, it would be worth considering the possibility of applying different types of surcharges to constructions located in high-risk areas. This system is even more necessary in a context of climate change and an ever-increasing frequency of natural disasters. Furthermore, we propose the establishment of adequate funding for river basin authorities to provide them with more resources. This financial support is key to encouraging decision-makers to carry out forecasting and warning measures to reduce flood damage.

The implementation of a two-tier insurance system—comprising private coverage for minor risks and a tax-funded public scheme—could, in theory, incentivize greater risk prevention among policyholders with respect to low-impact flood events. However, it could also give rise to moral hazard, as the assurance that all flood-related losses are ultimately covered by the CCS might reduce incentives for preventive action, particularly in areas prone to non-catastrophic flooding.

Nevertheless, with appropriate system design, the first tier could effectively encourage mitigation efforts for manageable risks, while ensuring that extreme events—those beyond the capacity of private insurance mechanisms—remain covered through general solidarity. This second tier would be financed via taxation and administered by the CCS, thereby preserving social protection without undermining individual responsibility.

The objectives proposed in this document are intended to emphasize the qualitative aspects over the quantitative aspects of the flood loss coverage model. We are aware that there is still a need for further exploration of the methods used to evaluate these risks to achieve a fair and sustainable pricing system, as well as the determination of the point at which the aggregate loss generated by a single event is sufficiently high to be classified as an extreme or catastrophic loss.

A hybrid system could be effective if mechanisms such as cross-subsidies, prevention incentives, and advanced technologies for more accurate risk assessment are properly implemented. These measures can help address affordability challenges without neglecting the need to align premiums with actual risk exposure. In the long term, a transparent and incentive-based system could encourage greater responsibility among policyholders without creating unsustainable economic disparities.

To prevent premiums from becoming excessively high in geographically vulnerable areas, it is proposed that low-risk zones contribute to financing premiums in high-risk areas, thus preserving affordability while maintaining a fair risk-based pricing structure.

The current model is designed to provide universal coverage against extraordinary risks such as floods, earthquakes, or major catastrophes. However, under a new two-tier approach, the CCS budget could be significantly adjusted.

One of the main policy implications of the proposed model lies in the need to reallocate the current CCS budget, concentrating its resources exclusively on the coverage of catastrophic risks and thus freeing financial capacity to respond more effectively to high-impact events. This reorientation would also allow part of the budget to be allocated to funding prevention incentives, such as premium discounts, subsidies for resilient infrastructure, or educational programs in risk management. Moreover, to ensure territorial equity, it would be necessary to establish cross-subsidy mechanisms to prevent highly vulnerable areas from facing unaffordable premiums, thereby preserving equal access to insurance coverage. The financial sustainability of the system would require the establishment of a clear framework for funding and governance, with coordinated participation from both the public and private sectors. Taken together, these measures would help develop a more efficient, equitable, and resilient system in the face of extreme weather events, aligning public policy with the objectives of risk prevention and climate adaptation.

Future research could apply a technical actuarial model to establish the threshold between what may or may not be considered an extraordinary natural event.