The State Political Doctrine: A Structural Theory of Transboundary Water and Foreign Policy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Evolution of the Doctrine Notion

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Current Research and Objective

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

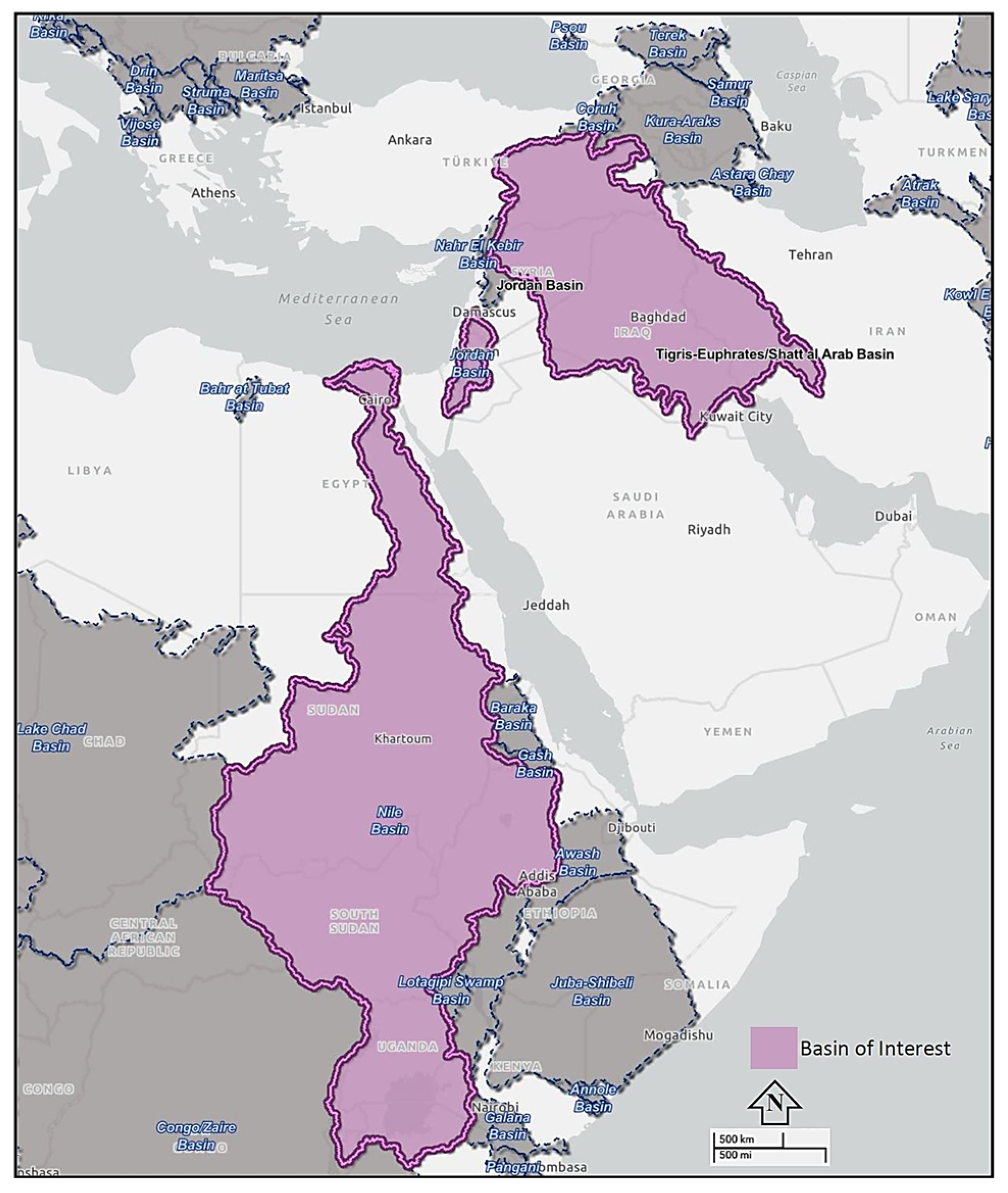

3.1. Water and Geopolitics in the MENA Region

3.1.1. The Euphrates–Tigris Basins (ETBs)—The Water-Bank Doctrine

3.1.2. Jordan River Basin (JRB)—Identity-Seeking Doctrine

3.1.3. Nile River Basin (NRB)—The Nation Rise Power Doctrine

3.2. The Quantitative Dimensions of Transboundary Water Allocation and the State Political Doctrine

3.3. The Dialectic of Water Dynamic, International Relations, and Time Factor

3.4. The Price of Local Governance Failure, Where Small Cracks Grow into Wide Breaks

4. Discussion

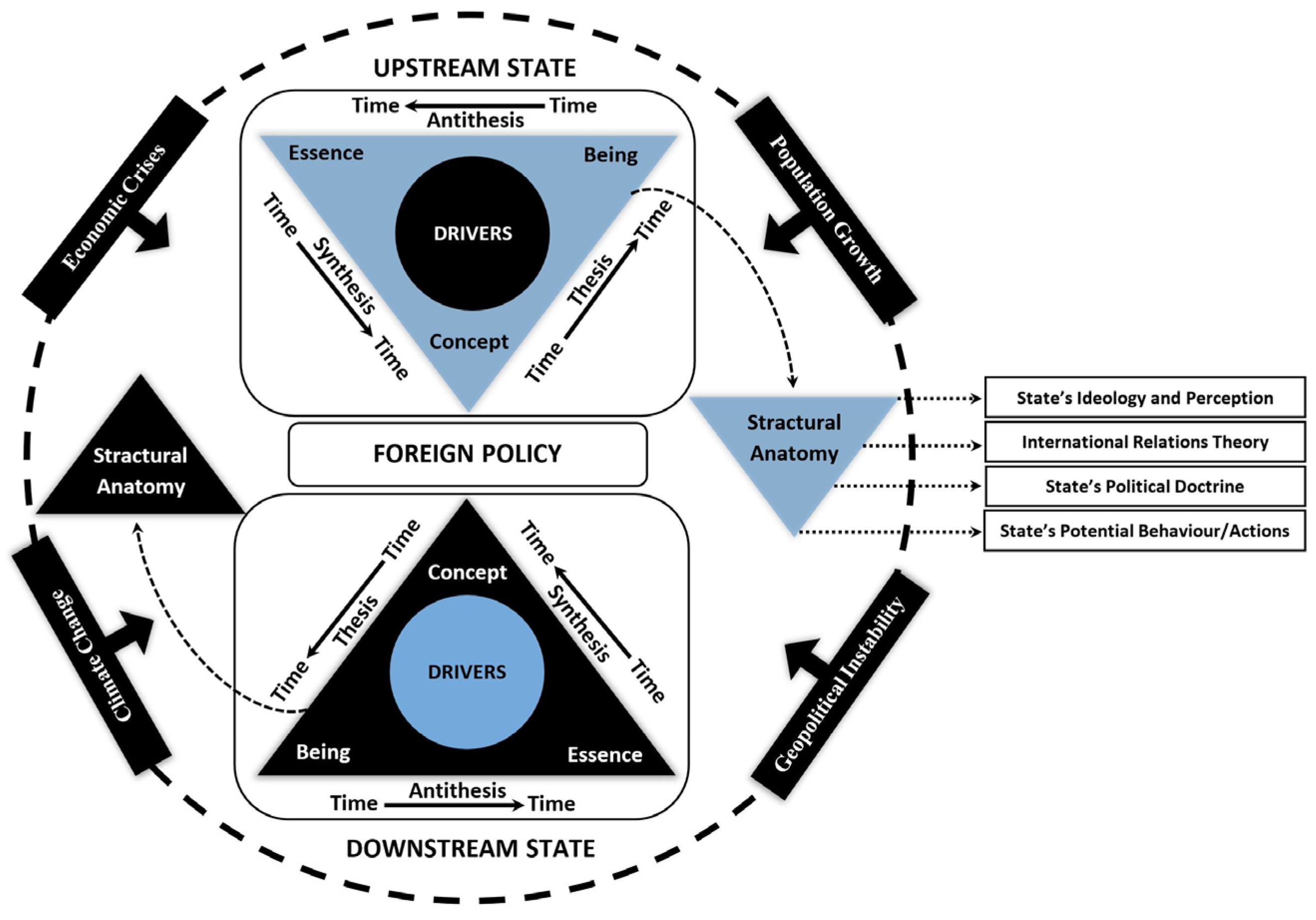

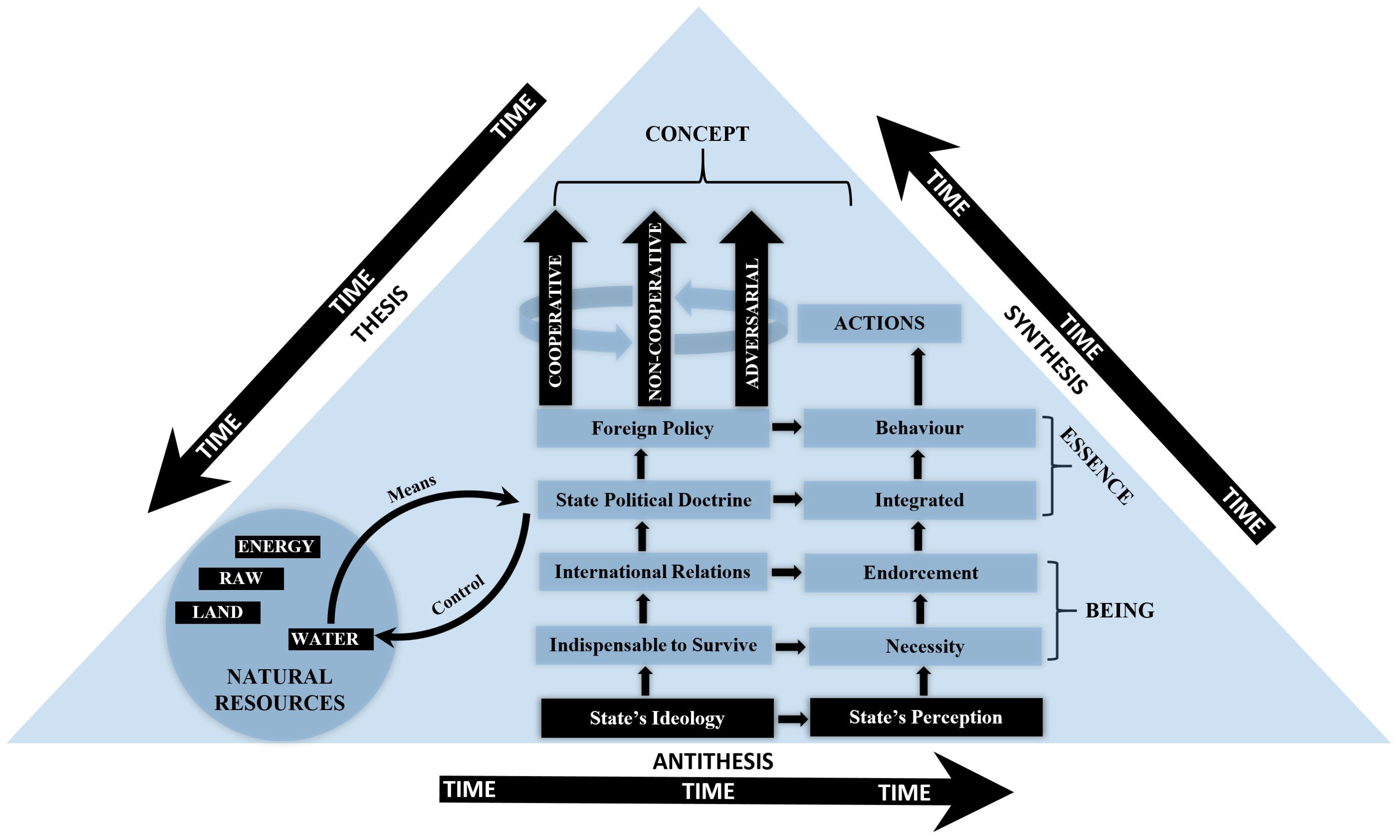

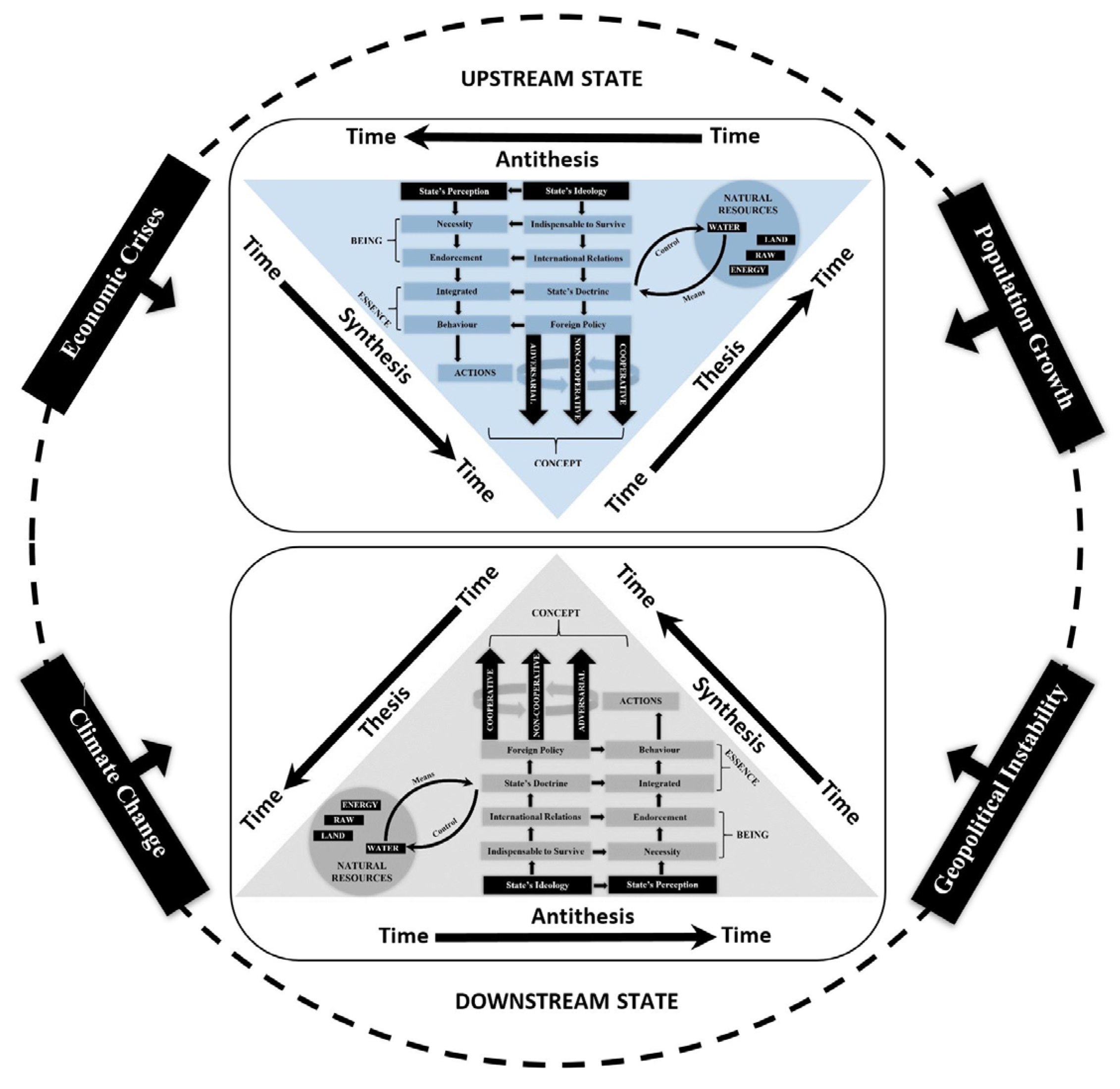

4.1. The Geometry and Structural Anatomy of State Political Doctrine

4.1.1. The Bond Between a State’s Being and Survival: The Cost of Sovereignty

4.1.2. Essence and the Geist of Foreign Policy: Pursuit of National Interest

4.1.3. Synthesizing Being and Essence: The Concept and the State’s Actions

4.2. From Hegel to Toynbee, the Golden Mean of Challenge and Response

4.3. The Potential Impact of Key External Challenges on the State Political Doctrine

4.4. The Dialectic of the SPD Between Idealism and Dialectical Materialism

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SPD | State Political Doctrine. |

| MENA | The Middle East and South Africa. |

| GERD | The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. |

| AGS | The Arab Gulf States. |

| ETBs | The Euphrates–Tigris Basins. |

| JRB | The Jordan River Basin. |

| NRB | The Nile River Basin. |

| GAP | The Southeastern Anatolia Project. |

| PKK | The Kurdistan Workers’ Party. |

| SDF | The Syrian Democratic Forces. |

| NWC | The National Water Carriers. |

| GDP | The Gross Domestic Product. |

| AHD | The Aswan High Dam. |

| SCC | The Suez Canal Company. |

| SDGs | The Sustainable Development Goals. |

| ISIS | The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. |

References

- Rahaman, M.M.; Varis, O. Integrated water resources management: Evolution, prospects and future challenges. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2005, 1, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olafson, M.K. The concept of limited sovereignty and the immigration law plenary power doctrine. Geo. Immigr. LJ 1998, 13, 433. [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey, S.C. The harmon doctrine one hundred years later: Buried, not praised. Nat. Resour. J. 1996, 36, 965. [Google Scholar]

- Gleick, P.H. The human right to water. Water Policy 1998, 1, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Som, C.; Hilty, L.M.; Köhler, A.R. The precautionary principle as a framework for a sustainable information society. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.J.; Blasco, D.; Carbonell, M. The Ramsar Convention Manual: A Guide to the Convention on Wetlands; Ramsar Convention Bureau: Ramsar, Iran, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, S.M.A. The Helsinki Rules, the UN Watercourses Convention and the Berlin Rules: Perspectives on international water law. Water Resour. Dev. 2007, 23, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive, W.F. EU Water framework directive. EC Dir. 2000, 60. Available online: https://lakeohridniva.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/eu-water-framework-directive-brochure.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Peichert, H. The Nile basin initiative: A catalyst for cooperation. In Security and Environment in the Mediterranean: Conceptualising Security and Environmental Conflicts; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 761–774. [Google Scholar]

- Laes, C. A Cultural History of Education in Antiquity; Bloomsbury Publishing Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Press, G.A. Doctrina’in Augustine’s “De doctrina christiana”. Philos. Rhetor. 1984, 98–120. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40237392 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Wofford, C.B. The Structure of Legal Doctrine in a Judicial Hierarchy. J. Law Court. 2019, 7, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, C. Plato’s Doctrine Of Forms: Modern Misunderstandings. Bachelor’s Thesis, Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Evrigenis, I.D. The doctrine of the mean in Aristotle’s ethical and political theory. Hist. Polit. Thought 1999, 20, 393–416. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, I. Theory of Ethics; Longmans: London, UK, 1873. [Google Scholar]

- Hegel, G.W.F. Science of Logic; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014; ISBN 1315823543. [Google Scholar]

- Löwith, K. Nietzsche’s Doctrine of eternal recurrence. In Sämtliche Schriften: Band 6: Nietzsche; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 415–426. [Google Scholar]

- Lax, J.R. The new judicial politics of legal doctrine. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2011, 14, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, A. Social Theory of International Politics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; Volume 67, ISBN 0521469600. [Google Scholar]

- Van Sang, N.; Tien, N.T.K. The Monroe Doctrine (1823): Origins, Principles and Effects. UED J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Educ. 2018, 8, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Anistratenko, T. Ideological Justification of the Truman Doctrine of 1947; Repository of the Ivan Franko Drohobych State Pedagogical University: Drogobych, Ukraine, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.A. The Soviet Concept of’Limited Sovereignty’from Lenin to Gorbachev: The Brezhnev Doctrine; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; ISBN 1349204919. [Google Scholar]

- Gooler, D.L.; COL, I.N.F. The Nixon Doctrine—Is There a Role for the US Army? Policy 1972, 95–114. Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD0763246.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Fund, S. Sustainable Development Goals. 2015. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/106391567056944729/pdf/World-Bank-Group-Partnership-Fund-for-the-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Annual-Report-2019.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Solanes, M. Integrated water management from the perspective of the Dublin Principles. CEPAL Rev. 1998, 1998, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzmaurice, M. Convention on the law of the non-navigational uses of international watercourses. LJIL 1997, 10, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J. Canadian-United States Practice and Theory Respecting the International Law of International Rivers: A Study of the History and Influence of the Harmon Doctrine. Can. B Rev. 1959, 37, 393. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, T. The Middle East Water Question; I.B. Tauris & Co., Ltd.: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, R.C. The application of water market doctrines in Texas. In Markets for Water: Potential and Performance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; pp. 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gümplová, P. Sovereignty over natural resources–A normative reinterpretation. Glob. Const. 2020, 9, 7–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adar, K.G. Kenya’s foreign policy and geopolitical interests: The case of the Nile River Basin. African Sociol. Rev. Africaine Sociol. 2007, 11, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hassan, H.A.; Rasheedy, A. Al The Nile River and Egyptian foreign policy interest. African Sociol. Rev. Africaine Sociol. 2007, 11, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, R.A. At The Intersection of Cooperation and Conflict: How Increased Tension and Mistrust Among Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan Shape the Negotiations on The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance DAM. Ph.D. Thesis, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Arfan, M.; Ansari, K.; Ullah, A.; Hassan, D.; Siyal, A.A.; Jia, S. Agenda setting in water and IWRM: Discourse analysis of water policy debate in Pakistan. Water 2020, 12, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumm, M.C.; Wood, M.C. The Public Trust Doctrine in Environmental and Natural Resources Law; Carolina Academic Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lanko, D.A.; Nechiporuk, D.M. International Politics of Russia’s Water Strategy. Russ. J. World Polit. Law Nations 2023, 1, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Abadía, B. Utopian River Planning and Hydrosocial Territory Transformations in Colombia and Spain. Water 2023, 15, 2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorr, K.K. No Trespassing: The Legal Origins of Louisiana’s Water Access Dispute. J. Civ. Law Stud. 2023, 15, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ayesha, S.; Naseem, I. Impact of climate change on foreign policy of south asian counrties. Int. Res. J. Relig. Stud. 2024, 4, 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Darwisheh, H. Geopolitics of Transboundary Water Relations in the Eastern Nile Basin. IDE Discuss. Pap. 2024, 921, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Şenyurt, S.E.; Taşkın, M.Ö. The Other Face of Turkey’s Foreign Policy in Sub-Saharan Africa: Soft Power Policy in Somalia. Florya Chronicles Polit. Econ. 2024, 10, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitoun, M. Violations, opportunities and power along the Jordan river: Security studies theory applied to water conflict. In Water Resources in the Middle East: Israel-Palestinian Water Issues—From Conflict to Cooperation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 213–223. [Google Scholar]

- Yihdego, Z.; Rieu-Clarke, A.; Cascão, A.E. How has the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam changed the legal, political, economic and scientific dynamics in the Nile Basin? Water Int. 2016, 41, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hussein, H. Yarmouk, Jordan, and Disi basins: Examining the impact of the discourse of water scarcity in Jordan on transboundary water governance. Mediterr. Polit. 2019, 24, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conker, A.; Hussein, H. Hydraulic mission at home, hydraulic mission abroad? Examining Turkey’s regional “Pax-Aquarum” and its limits. Sustainability 2019, 11, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoudy, M. Water weaponization in the Syrian conflict: Strategies of domination and cooperation. Int. Aff. 2020, 96, 1347–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, D.; Hall, J.; Murgatroyd, A.; Wheeler, K. Should Egypt be afraid of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam? The consequences of adversarial water policy on the Blue Nile. Water Policy 2025, 27, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearsheimer, J.J.; Rosato, S. How States Think: The Rationality of Foreign Policy; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2023; ISBN 0300269307. [Google Scholar]

- Maybee, J.E. Hegel’s Dialectics. 2016. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hegel-dialectics/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Toynbee, A.J. A Study of History: Volume I: Abridgement of Volumes I–VI; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; Volume 1, ISBN 0195050800. [Google Scholar]

- Oregon State University. Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database Cartographer: Melissa McCracken, Robinson Projection. 2017. Available online: https://oregon-explorer.apps.geocortex.com/webviewer/?app=d8e735e546784237b0e598ee7f4f2522 (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- World Bank Group. Iraq Reconstruction and Investment Part 2 Damage and Needs Assessment of Affected Governorates; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Volume 1, Available online: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/600181520000498420/pdf/123631-REVISED-Iraq-Reconstruction-and-Investment-Part-2-Damage-and-Needs-Assessment-of-Affected-Governorates.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Sowers, J.; Vengosh, A.; Weinthal, E. Climate change, water resources, and the politics of adaptation in the Middle East and North Africa. Clim. Change 2011, 104, 599–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelis, D.L.; Waterhouse, J.C. Equilibrium and nonequilibrium concepts in ecological models. Ecol. Monogr. 1987, 57, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, R.H., Jr.; Scoones, I.; Kerven, C. Range Ecology at Disequilibrium: New Models of Natural Variability and Pastoral Adaptation in African Savannas. J. Int. Afr. Inst. 1994, 64, 581–583. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, W.A.; Farid, A.M.; Sirriyeh, H. Development Projects on the Euphrates. In Israel and Arab Water; Arab Research Centre: London, UK; pp. 69–74.

- Plc, B.P. CHAR 17/14, The Sir Winston Churchill Archive Trust and content, 2002, Mesopota, ia, Principal Outstanding Question; Bloomsbury Publishing Plc: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, H.; Conker, A.; Grandi, M. Small is beautiful but not trendy: Understanding the allure of big hydraulic works in the Euphrates-Tigris and Nile waterscapes. Mediterr. Polit. 2022, 27, 297–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Muqdadi, S.W.; Omer, M.F.; Abo, R.; Naghshineh, A. Dispute over Water Resource Management—Iraq and Turkey. J. Environ. Prot. 2016, 7, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadekar, S.B. Water Dispute in the Middle East: The Euphrates-Tigris Basin. Soc. Res. 2014, 2, 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Muqdadi, S.W.H. Theories of International Relations and the Hydropolitical Cycle: The Hydro-Trap and the Anarchic Nature of Water Conflict. In Theorizing Transboundary Waters in International Relations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Gür, N.; Tatliyer, M.; Dilek, Ş. The Turkish Economy at the Crossroads. Insight Turk. 2019, 21, 135–160. [Google Scholar]

- Pinfold, R.G. Myth Busting in a Post-Assad Syria. Middle East Policy 2025, 32, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, M. The water-energy-food nexus: A holistic approach for resource security in Iran, Iraq, and Turkey. Water-Energy Nexus 2020, 3, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Muqdadi, S.W.H.; Khalaifawi, A.; Abdulrahman, B.; Kittana, F.A.; Alwadi, K.Z.; Abdulkhaleq, M.H.; Al Saffar, S.S.; Al Taie, S.M.; Merza, S.; Al Dahmani, R. Exploring the challenges and opportunities in the Water, Energy, Food nexus for Arid Region. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2020, 9, 1080355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleick, P. The Three Ages of Water: Prehistoric Past, Imperiled Present, and a Hope for the Future; Hachette: New York, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 1541702298. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Muqdadi, S.W.H. The Spiral of Escalating Water Conflict: The Theory of Hydro-Politics. Water 2022, 14, 3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitoun, M.; Warner, J. Hydro-hegemony–a framework for analysis of trans-boundary water conflicts. Water Policy 2006, 8, 435–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolars, J.F.; Mitchell, W.A. The Euphrates River and the Southeast Anatolia Development Project; SIU Press: Carbondale, IL, USA, 1991; ISBN 0809315726. [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu, D. Addressing Inadequate Transboundary Water Cooperation in the Euphrates and Tigris Basin: The Guidance of Systems Thinking. Master’s Thesis, Oregon State University: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Elhance, A.P. Hydropolitics in the Third World: Conflict and Cooperation in International RIVER Basins; US Institute of Peace Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; ISBN 1878379917. [Google Scholar]

- Kolars, J. The hydro-imperative of Turkey’s search for energy. Middle East J. 1986, 40, 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kibaroglu, A.; Scheumann, W. Evolution of transboundary politics in the Euphrates-Tigris river system: New perspectives and political challenges. Glob. Gov. 2013, 19, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlman, C. Turkey’s accession to the European Union: The geopolitics of enlargement. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2004, 45, 553–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Muqdadi, S.W.H. Developing strategy for water conflict management and transformation at Euphrates-Tigris basin. Water 2019, 11, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugom, L. Turkish foreign policy under Erdogan: A change in international orientation? Comp. Strateg. 2019, 38, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab Research Center. Tigris-Euphrates Issues; Arab Research Center: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli, I. From Coal and Steel Community to Eurozone: An Imperfect Economic Integration. Master’s Thesis, Università Ca’ Foscari, Venice, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Foreign Policy. The Future of Water Wars. 2011. Available online: https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/05/05/the-future-of-water-wars/ (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Al-Abbasy, R.T.M. Turkey’s Peace Water Pipeline Project and the Emirati Position to it. Reg. Stud. J. 2021, 15. Available online: https://uomosul.edu.iq/en/regionalstudiescenter/2020/01/08/seminar-13/ (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Kćbaroýlu, A. Politics of water resources in the Jordan, Nile and Tigris-Euphrates: Three river basins, three narratives. Percept. J. Int. Aff. 2007, 12, 143–164. [Google Scholar]

- Tripp, C. A History of Iraq; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; ISBN 052152900X. [Google Scholar]

- CHAR 17/13A; The Sir Winston Churchill Archive Trust and Content, 2002, Foreign Relations of Mesopotamia Under the Mandate, Classified Secret Document as Property of His Britannic Majesty’s Government. Colonial Office: London, UK, 2023.

- Del Sarto, R.A. Contentious borders in the Middle East and North Africa: Context and concepts. Int. Aff. 2017, 93, 767–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allawi, A.A. Faisal I of Iraq; Yale University Press: New Haven, UK, 2014; ISBN 0300127324. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, G. Ancient Iraq; Penguin: London, UK, 1992; ISBN 0141938250. [Google Scholar]

- Mazlum, I. ISIS as an actor controlling water resources in Syria and Iraq. In Violent Non-State Actors Syrian Civ. War ISIS YPG Cases; Oktav, Ö., Parlar Dal, E., Kurşun, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Barkey, H.J. Turkey and Iraq: The making of a partnership. Turkish Stud. 2011, 12, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeynep Oktav Alantar, Ö. The October 1998 Crisis: The Change of Heart of Turkish Foreign Policy towards Syria? CEMOTI Cah. d’Études sur la Méditerranée Orient. le monde Turco-Iranien 2001, 31, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kibaroglu, A.; Scheumann, W. Euphrates-Tigris rivers system: Political rapprochement and transboundary water cooperation. In Turkey’s Water Policy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 277–299. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, H.J. Turkey’s Gap Project from the Perspective of International Water Law. Iran. J. Int. Comp. Law 2023, 1, 150–174. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, T. Is the pyd a continuation of the pkk an ideological analysis of the concepts of democratic confederalism and democratic autonomy. Terörizm ve Radikalleşme Araştırmaları Derg. 2024, 3, 239–272. [Google Scholar]

- BBC. “We Are Still at War”: Syria’s Kurds Battle Turkey Months After Assad’s Fall. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c4g0w0x28yxo (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Syria Observatory of Human Rights after Sneaking to Western Bank of Euphrates River|“SDF” Captures Four Turkish Soldiers on Frontline of Qorah Qozak 2025. Available online: https://www.syriahr.com/en/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/SOHR-booklet-comprising-17-reports-with-infographics-summarises-all-key-developments-in-Syria-in-2024-1.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- The Guardian PKK Declares Ceasefire with Turkey After More Than 40 Years of Conflict. 2025. Available online: https://www.voanews.com/a/pkk-declares-ceasefire-with-turkey-after-40-years-of-armed-struggle-/7993837.html (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Rudaw. Sdf Says Ocalan’s Call for Pkk Disarmament, Dissolution Does not Apply to Them. 2025. Available online: https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/270220252 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- U.S. Department of State. Agreement Between the Syrian Interim Authorities and the Syrian Democratic Forces; U.S. Department of State: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.state.gov/agreement-between-the-syrian-interim-authorities-and-the-syrian-democratic-forces/ (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Jones, C.; Sultan, M.; Yan, E.; Milewski, A.; Hussein, M.; Al-Dousari, A.; Al-Kaisy, S.; Becker, R. Hydrologic impacts of engineering projects on the Tigris–Euphrates system and its marshlands. J. Hydrol. 2008, 353, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, R.A.; Rahi, K.A.; Abudi, Z.N. Water budget for abu zirig marsh in Southern Iraq. J. Eng. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 22, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challoob Bari, A. Turkey’s Goals of the GAP Project and its Effects on Iraq’s Economy. Mesopotamian Polit. Stud. 2023, 2, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, H.; Abdul Rahim, A.; Anuar, H.M. Water Projects by Turkey and Iran: The Impacts on the Right of Iraq to Access Equitable Share of Water. Resmilitaris 2022, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Qadir, S.A. Integrated Water Resources Management: Case Study of Iraq. Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Political Science, Public Administration and Diplomacy, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pilesjo, P.; Al-Juboori, S.S. Modelling the effects of climate change on hydroelectric power in Dokan, Iraq. Int. J. Energy Power Eng 2016, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Muqdadi, S.W.H.; Abdalwahab, N.S.; Almallah, I.A.R. The complex system of climate change security and the ripple effect of water-food-socioeconomic nexus. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibaroglu, A. Building a Regime for the Waters of the Euphrates-Tigris River Basin (Vol. 7). Brill. 2021. Available online: https://books.google.de/books?hl=en&lr=&id=AtBKEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR3&dq=Kibaroglu,+A.+2002.+Building+a+Regime+for+the+Waters+of+the+Euphrates-Tigris+River+Basin.+Leiden,+Martinus+Nijhoff+Publishers.+226/229-230.&ots=Y9vkulPQBx&sig=ZE_vBoRF32pa273LDodWE3 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Wolf, A.T. A long-term view of water and security: International waters, national issues and regional tensions. In The Jordan River and Dead Sea Basin; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Alatout, S. Hydro-Imaginaries and the construction of the political geography of the Jordan river. In Environmental Imaginaries of the Middle East North Africa; Ohio University Press: Athens, OH, USA, 2011; pp. 218–245. [Google Scholar]

- Lowi, M.R. Rivers of conflict, rivers of peace. J. Int. Aff. 1995, 49, 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Suleiman, R. Water resources development in the Jordan River Basin in Jordan. In Proceedings of the The 3rd Conference of the International Water History Association, Alexandria, Egypt, 11–14 December 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Feitelson, E. The four eras of Israeli water policies. In Water Policy in Israel: Context, Issues and Options; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Beschorner, N. Water and Instability in the Middle East; International Institute for Strategic Studies: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M. Agri-tech and Israel. In The Palgrave International Handbook of Israel; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, D.J.H.; Attili, S.; McCaffrey, S.; Murray, J.S. The Jordan River Basin: 1. Clarification of the allocations in the Johnston plan. Water Int. 2007, 32, 16–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosland, J.K. Cooperating Rivals: The Riparian Politics of the Jordan River Basin; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 0791479579. [Google Scholar]

- Jonathan, C. Randal Low Key Talks Bring Opposing Parties Together. The Washington Post 1992.

- Atkinson, E.; Burgess, J. Israel Plans to Expand Golan Settlements After Fall of Assad. BBC, 2024. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cz6lgln128xo (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Cooper, T.; Sandler, E. The June 1967 Arab-Israeli Six-Day War; Torrossa: Warwick, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Blum, Y.Z. From Camp David to Oslo. Isr. Law Rev. 1994, 28, 211–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, N. Futile Diplomacy: The United Nations, the Great Powers and Middle East Peacemaking 1948–1954; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013; ISBN 1315037807. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, R.O. Israel and the United States. Contemp. Isr. 2018, 253–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L. Implementation constraints on Israel–Palestine water cooperation: An analysis using the water governance assessment framework. Water 2021, 13, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seminar, E.P.; Regev, T. Seminar Policy Paper–10 July 2017. Available online: https://www.runi.ac.il/media/iellyydx/15.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Eyl-Mazzega, M.-A.; Cassignol, É. The Geopolitics of Seawater Desalination; Études l’Ifri, Ifri: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, M. Water scarcity and degradation in Palestine as challenges, vulnerabilities, and risks for environmental security. In Coping with Global Environmental Change, Disasters and Security: Threats, Challenges, Vulnerabilities and Risks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 409–419. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, E.; Sabel, R. Water and Diplomacy in the Jordan River Basin. Isr. J. Foreign Aff. 2009, 3, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imani, F. Hydropolitics: Exploring the Intersection of Water, security, and Conflict in the Middle East, Case studies: The Nile and Jordan Basins. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376782618_Hydropolitics_Exploring_the_Intersection_of_Water_security_and_Conflict_in_the_Middle_East_Case_studies_the_Nile_and_Jordan_Basins (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Borthwick, B. Water in Israeli-Jordanian relations: From conflict to the danger of ecological disaster. Isr. Aff. 2003, 9, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratoglu, A.; Wassar, F. Water at the intersection of human rights and conflict: A case study of Palestine. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1470201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, J. Power and Water in Jordan and Israel: An Exploration of Hydro-Hegemony in the post-Peace Treaty Era; University of Ottawa: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Haddadin, M.J. Diplomacy on the Jordan: International Conflict and Negotiated Resolution; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 21, ISBN 1461515130. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, E.L. Decisions in Israel’s Foreign Policy, by Michael Brecher; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ohlsson, L.; Turton, A.R. The Turning of a Screw: Social Resource Scarcity as a Bottle-Neck in Adaptation to Water Scarcity; Occasional Papers Series of the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) Water Study Group; University of London: London, UK, 1999; pp. 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Arlosoroff, S. Water Demand management—A strategy to deal with water scarcity: Israel as a case study. In Water Resources in the Middle East: Israel-Palestinian Water Issues—From Conflict to Cooperation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 325–330. [Google Scholar]

- Livnat, A. Desalination in Israel: Emerging key component in the regional water balance formula. Desalination 1994, 99, 299–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, S.N. The Jordan River and International Law. In The Jordan River Dispute; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1968; pp. 46–70. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, D.; Ngoga, T.; Said, J.; Yachin, M. How Israel Became a World Leader in Agriculture and Water; The Tony Blair Institute for Global Change: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 2001–2020. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. High-Tech Industry Share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in Israel from 2013 to 2023. 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1550512/israel-annual-hightech-product-share-of-gdp/#:~:text=In2023%2Cthehigh-tech,outputgrewovernine-fold (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Hitman, G.; Zwilling, M. Normalization with Israel: An analysis of social networks discourse within Gulf States. Ethnopolitics 2022, 21, 423–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podeh, E. The many faces of normalization: Models of Arab-Israeli relations. Strateg. Assess. 2022, 25, 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- El Kurd, D. The paradox of peace: The impact of normalization with Israel on the Arab World. Glob. Stud. Q. 2023, 3, ksad042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoty, D.; Greidinger, M.; Neria, Y.; Segev, A.; Lurie, I. A prediction model of PTSD in the Israeli population in the aftermath of October 7th, 2023, terrorist attack and the Israel–Hamas war. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2024, 13, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, J.R. Water Wars; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991; pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Duna, C. Turkey’s peace pipeline. In The Politics of Scarcity; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, A.M. The Nile Basin Cooperative Framework Agreement: The beginning of the end of Egyptian hydro-political hegemony. Mo. Envtl. L. Pol’y Rev. 2010, 18, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amery, H.A.; Wolf, A.T. Water, geography, and peace in the Middle East: An introduction. In Water in the Middle East: A Geography of Peace; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2000; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Awange, J. The Nile Waters: Weighed from Space; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; ISBN 3030647560. [Google Scholar]

- Desalegn, H.; Damtew, B.; Mulu, A.; Tadele, A. Identification of potential sites for small-scale hydropower plants using a geographical information system: A case study on fetam river basin. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. A 2023, 104, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abtew, W.; Dessu, S.B. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the Blue Nile; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; ISBN 3319970941. [Google Scholar]

- Gleick, P.H.; Lowi, M.R. Water and Conflict; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kahsay, T.N.; Kuik, O.; Brouwer, R.; Van Der Zaag, P. The economy-wide impacts of climate change and irrigation development in the Nile Basin: A computable general equilibrium approach. Clim. Change Econ. 2017, 8, 1750004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adar, K.G.; Check, N.A. Cooperative Diplomacy, Regional Stability and National Interests: The Nile River and the Riparian States; African Books Collective: Oxford, UK, 2011; ISBN 0798302879. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Salam, M.E.; Negm, M.; Ardabb, C.S. The Egyptian Cotton; Current Constraints and Future Opportunities; Textile Industries Holding Co.: Alexandria, Egypt, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, S. Super Powers in the Middle East: An Overview. Pakistan Horiz. 1982, 35, 68–83. [Google Scholar]

- El-Labbad, M. Egypt: A “Regional Reference” in the Middle East. In Regional Powers in the Middle East: New Constellations After the Arab Revolts; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, J. Nasser: Hero of the Arab Nation; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 1780742002. [Google Scholar]

- Godana, B.A. Africa’s Shared Water Resources: Legal and Institutional Aspects of the Nile, Niger and Senegal River Systems; L. Rienner: Boulder, CO, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Staples, A.L.S. Seeing Diplomacy through Banker’s Eyes: The World Bank, the Anglo-Iranian Oil Crisis, and the Aswan High Dam. Dipl. Hist. 2002, 26, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissinger, H. Leadership: Six Studies in World Strategy; Penguin Group: London, UK, 2024; ISBN 0593489462. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, W.J. Economic aid and American Policy Toward Egypt, 1955–1981; Sunny Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1985; ISBN 0873958683. [Google Scholar]

- Dalachanis, A. Company and the Second World War. Italy Suez Canal, from Mid-Nineteenth Century to Cold War—A Mediterranean History; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; p. 313. [Google Scholar]

- Mohieldin, M.; Amin-Salem, H.; El-Shal, A.; Moustafa, E. Looking Back at How Egypt Got to Today. Polit. Econ. Cris. Manag. Reform Egypt 2024, 11–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haralambides, H. The Red Sea crisis and chokepoints to trade and international shipping. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2024, 26, 367–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, M.B. Six Days of War: June 1967 and the Making of the Modern Middle East; Presidio Press: Novato, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 0345464311. [Google Scholar]

- Holbik, K.; Drachman, E. Egypt as recipient of Soviet aid, 1955–1970. Z. Gesamte Staatswiss. /J. Institutional Theor. Econ. 1971, 137–165. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40749433 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Mohammed Basheer Cooperative operation of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam reduces Nile riverine floods. River Res. Appl. 2021, 37, 805–814. [CrossRef]

- Taye, M.T.; Tadesse, T.; Senay, G.B.; Block, P. The grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam: Source of cooperation or contention? J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2016, 142, 2516001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowidar, F. Redefining Power: The Deconstruction of Tensions Between Egypt and Ethiopia; Centre Sciences Po Pour La Recherche Strategique: Menton, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, L. Environmental Impacts of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on Egypt. Population 1960, 1990, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bouks, B. The Restrains on Egypt’s National Security Towards the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Secur. Sci. J. 2022, 3, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, J.; Soliman, A. Coordinating International Responses to Ethiopia-Sudan Tensions; Chatham House: London, UK, 2023; ISBN 1784135666. [Google Scholar]

- Shapland, G. Rivers of Discord: International Water Disputes in the Middle East; Hurst: London, UK, 1997; ISBN 1850652147. [Google Scholar]

- Seide, W.M.; Fantini, E. Emotions in Water Diplomacy: Negotiations on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. Water Altern. 2023, 16, 188–194. [Google Scholar]

- Wehling, P.; Wehling, P. The Treaty Regime for the Nile. In Nile Water Rights: An International Law Perspective; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 105–165. [Google Scholar]

- Røsberg, A.H. Egypt, Ethiopia, and the Nile. Understanding Egypt’s Refusal to Renegotiate the 1929 and 1959 Agreements Concerning Rights and Allocations of the Nile. Master’s Thesis, The Department of Political Science University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Woldesenbet, A.B. The Impact of Electricity Shortages on Large-and Medium-Scale Manufacturing Industries in Ethiopia; University of Cape Town: Cape Town, South Africa, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Akamo, J.O. The GERD from an Ethiopian Perspective: Actors, Interests and Instruments; Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI): Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Abdurrahim, A. The Establishment of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (Gerd) and the Structural Violence on Impacting Environment of Egypt 2018–2021; Universitas Islam Indonesia: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Woldemaryam, E. Making the Nile River a point of cooperation between Ethiopia and Egypt: Building confidence through water diplomacy. Bp. Int. Res. Critics Inst. J. 2020, 3, 2494–2500. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, S.M.A. The declaration of principles on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam: An analytical overview. In Ethiopian Yearbook of International Law 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 203–221. [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik, R.; Dombrowsky, I. GERD and hydropolitics in the Eastern Nile: From water-sharing to benefit-sharing. In The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam and the Nile Basin; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 113–137. [Google Scholar]

- Yihun, B.B. Battle over the Nile: The diplomatic engagement between Ethiopia and Egypt, 1956–1991. Int. J. Ethiop. Stud. 2014, 8, 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- Abtew, W. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) Filling and Operation. In Nile Water Conflict and the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrade. Ethiopia Uses GERD, Africa’s Largest Dam for Bitcoin Mining–Revenue Hits 18%. 2024. Available online: https://www.mitrade.com/insights/news/live-news/article-3-544335-20241227 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Kibaroglu, A. 8 The Euphrates–Tigris River Basin. In Sustainability of Engineered Rivers in Arid Lands: Challenge and Response; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- Gökalp, Z.; Çakmak, B. Agricultural water management in Turkey: Past-present-future. Curr. Trends Nat. Sci. 2016, 5, 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Eklund, L.; Thompson, D. Differences in resource management affects drought vulnerability across the borders between Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Treaty of Friendship and Neighborly Relations between Iraq and Turkey, Collection of Treaties; No. 580; Nations Unies-Recueil des Traités: New York, NY, USA, 1949; pp. 281–331. Available online: https://www.internationalwaterlaw.org/documents/regionaldocs/Iraq-Turkey-Friendship_1946.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Kibaroglu, A. Historical Review of Formal and Informal Water Institutions in the Euphrates-Tigris Region with a Specific Focus on Water Relations between Turkey and Iraq. In World Scientific Handbook of Transboundary Water Management: Science, Economics, Policy and Politics: Volume 3: The Role of Formal and Informal Institutions in Managing Transboundary Basins; World Scientific: Singapore, 2025; pp. 199–222. [Google Scholar]

- Zawahri, N.A. Stabilising Iraq’s water supply: What the Euphrates and Tigris rivers can learn from the Indus. Third World Q. 2006, 27, 1041–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, I.; Wihbey, P.M. The new water politics of the Middle East. Strateg. Rev. 1999, 27, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, M.; Akıncı, Z.S.; Bilgen, A.; Nasir, N.; Al-Rubaie, A. Towards Hydro-Transparency on the Euphrates-Tigris Basin: Mapping Surface Water Changes in Iraq, 1984–2015; London School of Economics and Political Science: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gafny, S.; Talozi, S.; Al Sheikh, B. Towards a Living Jordan River; Friends of the Earth Middle East: Amman, Jordan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zeitoun, M. Power and Water in the Middle East; I.B. Tauris & Co., Ltd.: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, J. Israel, Palestine, and the Oslo Accords. Fordham Int’l LJ 1999, 23, 230. [Google Scholar]

- Field, Z.M. Red-Dead Redemption? Applying and Critiquing Environmental Peacebuilding in Palestine, Jordan, and Israel. Mater’s Thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Talozi, S.; Altz-Stamm, A.; Hussein, H.; Reich, P. What constitutes an equitable water share? A reassessment of equitable apportionment in the Jordan-Israel water agreement 25 years later. Water Policy 2019, 21, 911–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, U.; Kaluarachchi, J.J. Climate change impacts on water resources in the upper blue Nile River Basin, Ethiopia 1. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2009, 45, 1361–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yihdego, Y.; Khalil, A.; Salem, H.S. Nile River’s basin dispute: Perspectives of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). Glob. J. Hum. Soc. Sci 2017, 17, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gari, Y.; Block, P.; Steenhuis, T.S.; Mekonnen, M.; Assefa, G.; Ephrem, A.K.; Bayissa, Y.; Tilahun, S.A. Developing an approach for equitable and reasonable utilization of international rivers: The Nile River. Water 2023, 15, 4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolters, W.; Smit, R.; Nour El-Din, M.; Sayed Ahmed, E.; Froebrich, J.; Ritzema, H. Issues and challenges in spatial and temporal water allocation in the Nile Delta. Sustainability 2016, 8, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, R.W. The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, a Problem in International Relations. J. Negro Hist. 1931, 16, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, I.H. The 1959 Nile Waters Agreement in Sudanese-Egyptian relations. Middle East. Stud. 1971, 7, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, S.M.A. Agreement on Declaration of Principles on the GERD: Interdependence or Leveling the Nile Basin Playing Field. In Complexity of Transboundary Water Conflicts: Enabling Conditions for Negotiating Contingent Resolutions; Anthem Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 145–172. [Google Scholar]

- El Baradei, S.A.; Abodonya, A.; Hazem, N.; Ahmed, Z.; El Sharawy, M.; Abdelghaly, M.; Nabil, H. Ethiopian dam optimum hydraulic operating conditions to reduce unfavorable impacts on downstream countries. Civ. Eng. J 2022, 8, 1906–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombelli, G.M.; Tomiet, S.; Bianchi, A.; Bocchiola, D. Impact of prospective climate change scenarios upon hydropower potential of Ethiopia in GERD and GIBE dams. Water 2021, 13, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamara, A.; Ahmed, M.; Benavides, A. Environmental and economic impacts of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam in Africa. Water 2022, 14, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.T. Indigenous approaches to water conflict negotiations and implications for international waters. Int. Negot. 2000, 5, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, G. Resource Wars: The New Landscape of Global Conflict. JSTOR 2003, 24, 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- Szálkai, K.; Szalai, M. Theorizing Transboundary Waters in International Relations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; ISBN 3031433750. [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont, P.; Blake, G.; Wagstaff, J.M. The Middle East: A Geographical Study; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; ISBN 1315628198. [Google Scholar]

- American Rivers Free Rivers: The State of Dam Removal in the U.S. 2022. Available online: https://www.americanrivers.org/2022/02/free-rivers-the-state-of-dam-removal-in-the-u-s/#:~:text=Arecorded1%2C957damshave,NewJersey(6Removals) (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Varsamidis, A. An Assessment of The Water Development Project (Gap) of Turkey Meeting its Objectives and EU Criteria for Turkey’s Accession; Naval Postgraduate School: Monterey, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tortajada, C. Evaluation of actual impacts of the Atatürk Dam. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2000, 16, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongerden, J. Dams and politics in Turkey: Utilizing water, developing conflict. Middle East Policy 2010, 17, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, T.N. The Securitization of Water in Israel Between 1948 and 2005. Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, U. The Golan Heights Under Israeli Occupation 1967–1981; University of Durham: Durham, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Quagliarotti, D. Al Will the Nile River Turn into a Lake? The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance (GERD) Dam Case-Study. Glob. Environ. 2023, 16, 478–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, A.; Bires, S.; Ayalew, W. Hydro-Political Dispute on Utilization of the Nile: Comparative Analysis of Toshka and Gerd Projects. SSRN 2025, 5184954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, M.; Bekhit, H.M. So near, yet so far: An Egyptian perspective on the US-facilitated negotiations on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. Water Int. 2023, 48, 580–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davutoğlu, A. Turkey’s zero-problems foreign policy. Foreign Policy 2010, 20, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tanzi, A.; Arcari, M. The United Nations Convention on the Law of International Watercourses: A Framework for Sharing; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 5, ISBN 9004420835. [Google Scholar]

- Priscoli, J.D.; Wolf, A.T. Managing and Transforming Water Conflicts; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; ISBN 0521632161. [Google Scholar]

- Burbidge, J. Concept and Time in Hegel. Dialogue Can. Philos. Rev. Can. Philos. 1973, 12, 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegel, G.W.F. Lectures on the Philosophy of World History; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1980; ISBN 0521281458. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkard, T. Hegel’s Phenomenology and Logic: An Overview’. In The Cambridge Companion to German Idealism; University of Notre Dame: Notre Dame, IN, USA, 2000; pp. 161–179. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, T.; Newig, J. Multilevel water governance and problems of scale: Setting the stage for a broader debate. Environ. Manag. 2010, 46, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.M. Water and conflict geographies of the Southeastern Anatolia Project. Soc. Natural Resour. 2002, 15, 743–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibaroglu, A. State-of-the-art review of transboundary water governance in the Euphrates–Tigris river basin. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2019, 35, 4–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carkoglu, A.; Eder, M. Domestic concerns and the water conflict over the Euphrates-Tigris river basin. Middle East. Stud. 2001, 37, 41–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, J. Cooperation, domination and colonisation: The Israeli-Palestinian joint water committee. Water Altern. 2013, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Woldesenbet, W.G.; Kebede, A.A. Multi-stakeholder collaboration for the governance of water supply in Wolkite, Ethiopia. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 7728–7755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Mahn, D.; Gebreyes, M.; Allouche, J.; Debarry, A. The water-energy-food nexus beyond “technical quick fix”: The case of hydro-development in the blue nile basin, Ethiopia. Front. Water 2022, 4, 787589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.; Baetens, F. The creation of states in international law. In Leading Works in International Law; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1979; pp. 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Waltz, K.N. Theory of International Politics; Waveland Press: Salem, WI, USA, 2010; ISBN 1478610530. [Google Scholar]

- Tucídides; Warner, R.; Finley, M.I. Thucydides: History of the Peloponnesian War; Penguin: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 0140440399. [Google Scholar]

- Machiavelli, N. The Prince; Wordsworth Editions: Hertfordshire, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenthau, H.; Nations, P.A. The Struggle for Power and Peace; MC Graw Hill: New, York, NY, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina, A.; Cozzi, G.; Mantovan, N. The evolution of ideology, fairness and redistribution. Econ. J. 2012, 122, 1244–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbes, T. Hobbes’s Leviathan; Рипoл Классик: Moscow, Russia, 1967; ISBN 5876352640. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, W.G.; De Wilde, J.H. The endurance of sovereignty. Eur. J. Int. Relat. 2001, 7, 283–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker Jr, R.M. The Endurance of Nationalism: Ancient Roots and Modern Dilemmas. J. Jew. Identities 2009, 2, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Mehlum, H.; Moene, K.; Torvik, R. Institutions and the resource curse. Econ. J. 2006, 116, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Haber, S.; Menaldo, V. Do natural resources fuel authoritarianism? A reappraisal of the resource curse. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2011, 105, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegels, A. Renewable energy in South Africa: Potentials, barriers and options for support. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 4945–4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrijvers, D.; Hool, A.; Blengini, G.A.; Chen, W.-Q.; Dewulf, J.; Eggert, R.; van Ellen, L.; Gauss, R.; Goddin, J.; Habib, K. A review of methods and data to determine raw material criticality. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Byerlee, D. Rising Global Interest in Farmland: Can It Yield Sustainable and Equitable Benefits? World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; ISBN 0821385925. [Google Scholar]

- Sadoff, C.W.; Grey, D. Beyond the river: The benefits of cooperation on international rivers. Water Policy 2002, 4, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norlen, T.; Sinai, T. The Abraham Accords–Paradigm Shift or Realpolitik; Marshall European Center for Security Studies: Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, 2020; Volume 64. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, O. Existential Threat Scenarios to the State of Israel; Institute for National Security Studies: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2020; ISBN 9659280629. [Google Scholar]

- Raijman, R.; Kemp, A. The new immigration to Israel: Becoming a de-facto immigration state in the 1990s. In Immigration Wordlwide; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 227–243. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=aaimTNHDzZYC&oi=fnd&pg=PA227&dq=250.%09Raijman,+R.%3B+Kemp,+A.+The+new+immigration+to+Israel:+Becoming+a+de-facto+immigration+state+in+the+1990s.+Immigr.+Worldw.+2010,+227%E2%80%93243&ots=GyG6GKvCUv&sig=4f9gLuo (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Lata, L. The Ethiopian State at the Crossroads: Decolonization and Democratization or Disintegration? The Red Sea Press: Trenton, NJ, USA, 1999; ISBN 156902121X. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, H.; Grandi, M. Dynamic political contexts and power asymmetries: The cases of the Blue Nile and the Yarmouk Rivers. Int. Environ. Agreem. Polit. Law Econ. 2017, 17, 795–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoa, R.B. The United Nations watercourses convention on the dawn of entry into force. Vand. J. Transnat’l L. 2014, 47, 1321. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Treaty Between Iraq and Turkey of Friendship and Neighbourly Relations, with Six Annexed Protocols; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1946; Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/fr/c/LEX-FAOC215679 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Allal, S.; O’Connor, M. Water Resource Distribution and Security in the Jordan-Israel-Palestinian Peace Process. In Environmental Change, Adaptation, and Security; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 109–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, K.G.; Basheer, M.; Mekonnen, Z.T.; Eltoum, S.O.; Mersha, A.; Abdo, G.M.; Zagona, E.A.; Hall, J.W.; Dadson, S.J. Cooperative filling approaches for the grand Ethiopian renaissance dam. Water Int. 2016, 41, 611–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitoun, M.; Eid-Sabbagh, K.; Talhami, M.; Dajani, M. Hydro-hegemony in the Upper Jordan waterscape: Control and use of the flows. Water Altern. 2013, 6, 86–106. [Google Scholar]

- Yergin, D. The New Map: Energy, Climate, and the Clash of Nations; Penguin: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 0241472350. [Google Scholar]

- Salameh, M.T.B.; Alraggad, M.; Harahsheh, S.T. The water crisis and the conflict in the Middle East. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2021, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddadin, M.J. Water scarcity impacts and potential conflicts in the MENA region. Water Int. 2001, 26, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Garcia, T.F. Climate change and violent conflict in the Middle East and North Africa. Int. Stud. Rev. 2023, 25, viad053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M. The Looming Climate and Water Crisis in the Middle East and North Africa. 2024. Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/12266655/the-looming-climate-and-water-crisis-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa/13162963/ (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Diep, L.; Hayward, T.; Walnycki, A.; Husseiki, M.; Karlsson, L. Water, Crises and Conflict in MENA: How Can Water Service Providers Improve Their Resilience? International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Roudi-Fahimi, F.; Creel, L.; De Souza, R.-M. Finding the Balance: Population and Water Scarcity in the Middle East and North Africa; Population Reference Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saidi, M.; Birnbaum, D.; Buriti, R.; Diek, E.; Hasselbring, C.; Jimenez, A.; Woinowski, D. Water resources vulnerability assessment of MENA countries considering energy and virtual water interactions. Procedia Eng. 2016, 145, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.J. The Kurdish regional constitutional within the framework of the Iraqi Federal Constitution: A struggle for sovereignty, oil, ethnic identity, and the prospects for a reverse supremacy clause. Penn St. Rev. 2009, 114, 707. [Google Scholar]

- Daher, J.; Mehchy, Z. Syria’s Economic Transition: From Kleptocracy to Islamic Neoliberalism in a War-Torn Economy. 2025. Available online: https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article8914 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Wolf, A.; Ross, J. The impact of scarce water resources on the Arab-Israeli conflict. Nat. Resour. J. 1992, 32, 919. [Google Scholar]

- Berhe, A. Revisiting resistance in Italian-occupied Ethiopia: The Patriots’ Movement (1936–1941) and the redefinition of post-war Ethiopia. In Rethinking Resistance: Revolt and Violence in African History; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 87–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.A.M.; Celia, D. Transboundary water conflicts as Postcolonial Legacy (the case of Nile Basin). Vestn. RUDN. Int. Relat. 2020, 20, 184–196. [Google Scholar]

- Ajjur, S.B.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Evapotranspiration and water availability response to climate change in the Middle East and North Africa. Clim. Change 2021, 166, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, H.; Öztürk, A.B. Global climate change, desertification, and its consequences in Turkey and the Middle East. In Climate Change and Global Public Health; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 445–458. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Obaidi, J.R.; Yahya Allawi, M.; Salim Al-Taie, B.; Alobaidi, K.H.; Al-Khayri, J.M.; Abdullah, S.; Ahmad-Kamil, E.I. The environmental, economic, and social development impact of desertification in Iraq: A review on desertification control measures and mitigation strategies. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comair, G.F.; McKinney, D.C.; Siegel, D. Hydrology of the Jordan River Basin: Watershed delineation, precipitation and evapotranspiration. Water Resour. Manag. 2012, 26, 4281–4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.A.; El Afandi, G.S.; El-Mahdy, M.E.-S. Impact of climate change on rainfall variability in the Blue Nile basin. Alexandria Eng. J. 2022, 61, 3265–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashwan, M.S.; Shahid, S. Future precipitation changes in Egypt under the 1.5 and 2.0 C global warming goals using CMIP6 multimodel ensemble. Atmos. Res. 2022, 265, 105908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, R.C. Water Resource Economics: The Analysis of Scarcity, Policies, and Projects; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; ISBN 0262334038. [Google Scholar]

- Ansink, E.; Houba, H. The economics of transboundary water management. In Handbook of Water Economics; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 434–466, ISBN 1782549668. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, M.; Keulertz, M.; Habibi, N.; Mulligan, M.; Woertz, E. Demographic and economic material factors in the MENA region. Middle East and North Africa Regional Architecture: Mapping Geopolitical Shifts, Regional Order and Domestic Transformations Working Papers. Int. Spect. 2017, 3, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Droogers, P.; Immerzeel, W.W.; Terink, W.; Hoogeveen, J.; Bierkens, M.F.P.; van Beek, L.P.H.; Negewo, B.D. Modeling water resources trends in Middle East and North Africa towards 2050. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2012, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naff, T. Water in the Middle East: Conflict or Cooperation? Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; ISBN 1000011232. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.; Winterman, K. Models and mandates in transboundary waters: Institutional mechanisms in water diplomacy. Water 2022, 14, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deribe, M.M.; Melesse, A.M.; Kidanewold, B.B.; Dinar, S.; Anderson, E.P. Assessing international transboundary water management practices to extract contextual lessons for the Nile river basin. Water 2024, 16, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.; Shafran, A. Transboundary exchanges of renewable energy and desalinated water in the Middle East. Energies 2019, 12, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, F. Dialectics of Nature; Wellred Books: North Aurora, IL, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K.; Engels, F. Collected Works [of] Karl Marx [and] Frederick Engles; Lawrence & Wishart: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig, F. Hegel and the State; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2023; ISBN 1000993086. [Google Scholar]

| Basin | Area (km2) | Population (2020) | Upstream Country | Riparian Countries |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euphrates–Tigris Basins (ETBs) | 868,989 | 82,804,133 | * Turkey | Iraq, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Jordan |

| Jordan River Basin (JRB) | 45,005 | 13,165,407 | Lebanon and * Israel | Jordan, Palestine, Syria |

| Nile River Basin (NRB) | 2,961,325 | 366,651,792 | * Ethiopia, South Sudan, Uganda | Egypt, Sudan, Abyei, Burundi, Congo, Eritrea, Hala’ib triangle, Kenya, Ma’tan al-Sarra, Rwanda, Tanzania |

| Basin/Upstream Country | Annual Water Flow | Agriculture Water Use % | Key Transboundary Agreements | The Impact of Dams on Downstream Flow |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euphrates–Tigris Basins (ETBs) Turkey | 68–84.5 BCM | 74 | Water flow reduction by 40% (Syria) and 80% (Iraq). Furthermore, 86% of the marshlands in Iraq have been reduced [190,191]. | |

| Jordan River Basin (JRB) Israel | 1.4 MCM | 55 | The total annual flow of JRB was reduced to ~200 MCM. And 40% of water allocation was reduced in Palestine and Jordan [192]. | |

| Nile River Basin (NRB) Ethiopia | 84 BCM | 85 | The GDP reduced by 8%, increased the unemployment rate by ~11%, decreased agricultural land by ~53%, and decreased food production by ~38% [206]. |

| Framework | Foundation | Mediation | Emergence | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hegel’s Science of Logic | Being:

| Essence:

| Concept: The unity of being and essence.

| Dynamic progression and ongoing evolution over time |

| Hegelian Dialectic | Thesis (initial position) | Antithesis (countering) | Synthesis (resolution) | |

| Arnold Toynbee Theory | Challenge (external pressure) | Golden Mean (equilibrium) | Response (adaptation) | |

| Basin (Upstream) | State’s survival threatened | State Political Doctrine | Actions | Consequences |

| Turkey (ETBs) | Energy shortage, national security, and joining the European Union | Water-Bank Doctrine | Absolute sovereignty | Water control/hegemony |

| Israel (JRB) | Regional conflicts and identity crises | Identity-Seeking Doctrine | Hegemony and tech diplomacy | Regional domination, excellence in Water Agritech to promote regional normalization |

| Ethiopia (NRB) | Anti-colonialism agreements and seeking national development | Nation Rise Power Doctrine | Regional hydropower hub | Hydropower dominance |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Muqdadi, S.W.H. The State Political Doctrine: A Structural Theory of Transboundary Water and Foreign Policy. Water 2025, 17, 1901. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17131901

Al-Muqdadi SWH. The State Political Doctrine: A Structural Theory of Transboundary Water and Foreign Policy. Water. 2025; 17(13):1901. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17131901

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Muqdadi, Sameh W. H. 2025. "The State Political Doctrine: A Structural Theory of Transboundary Water and Foreign Policy" Water 17, no. 13: 1901. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17131901

APA StyleAl-Muqdadi, S. W. H. (2025). The State Political Doctrine: A Structural Theory of Transboundary Water and Foreign Policy. Water, 17(13), 1901. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17131901