Meaningful Multi-Stakeholder Participation via Social Media in Coastal Fishing Village Spatial Planning and Governance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

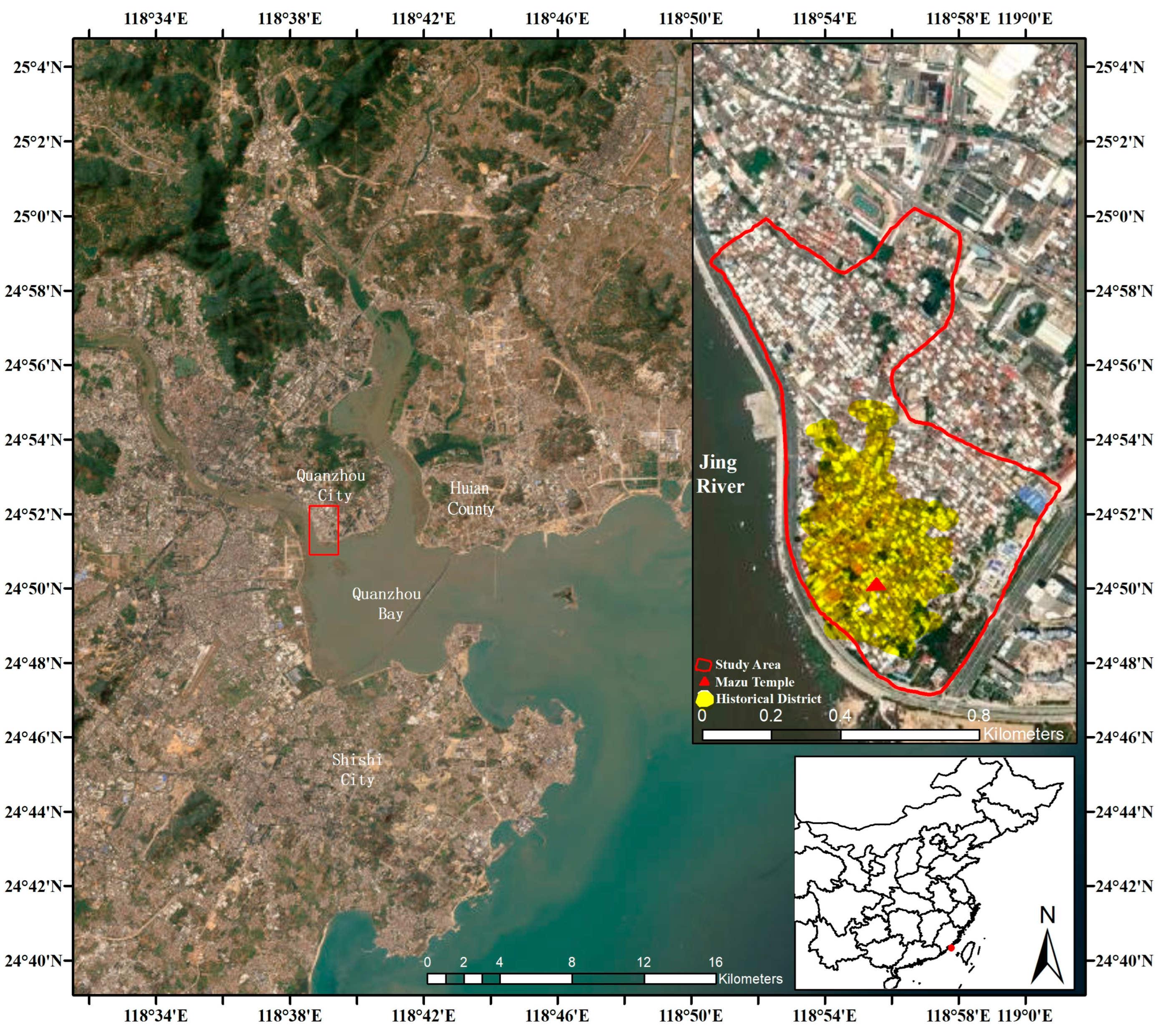

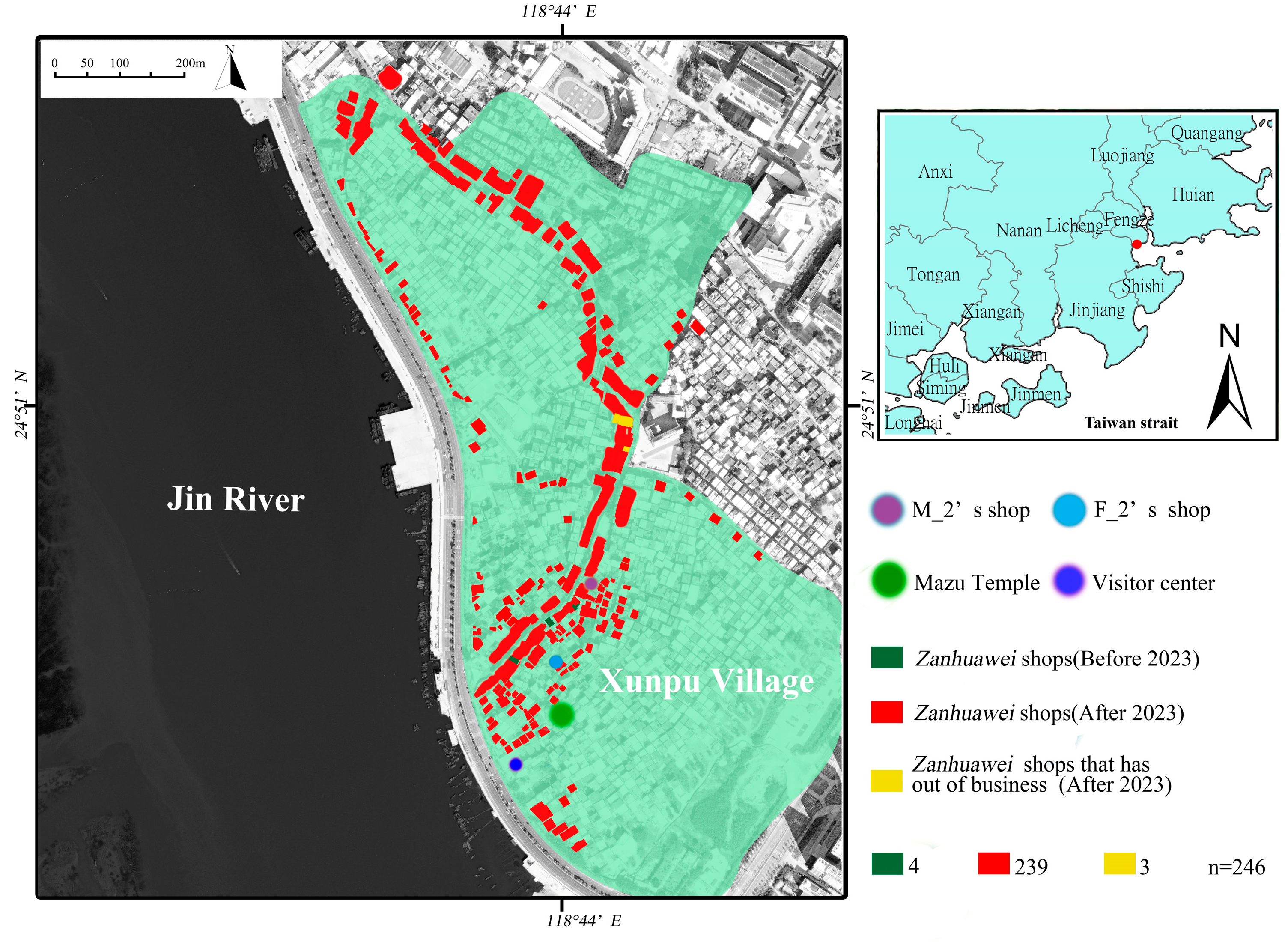

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Study Methods

3. Results

3.1. Transformation of Fishing Village Economy

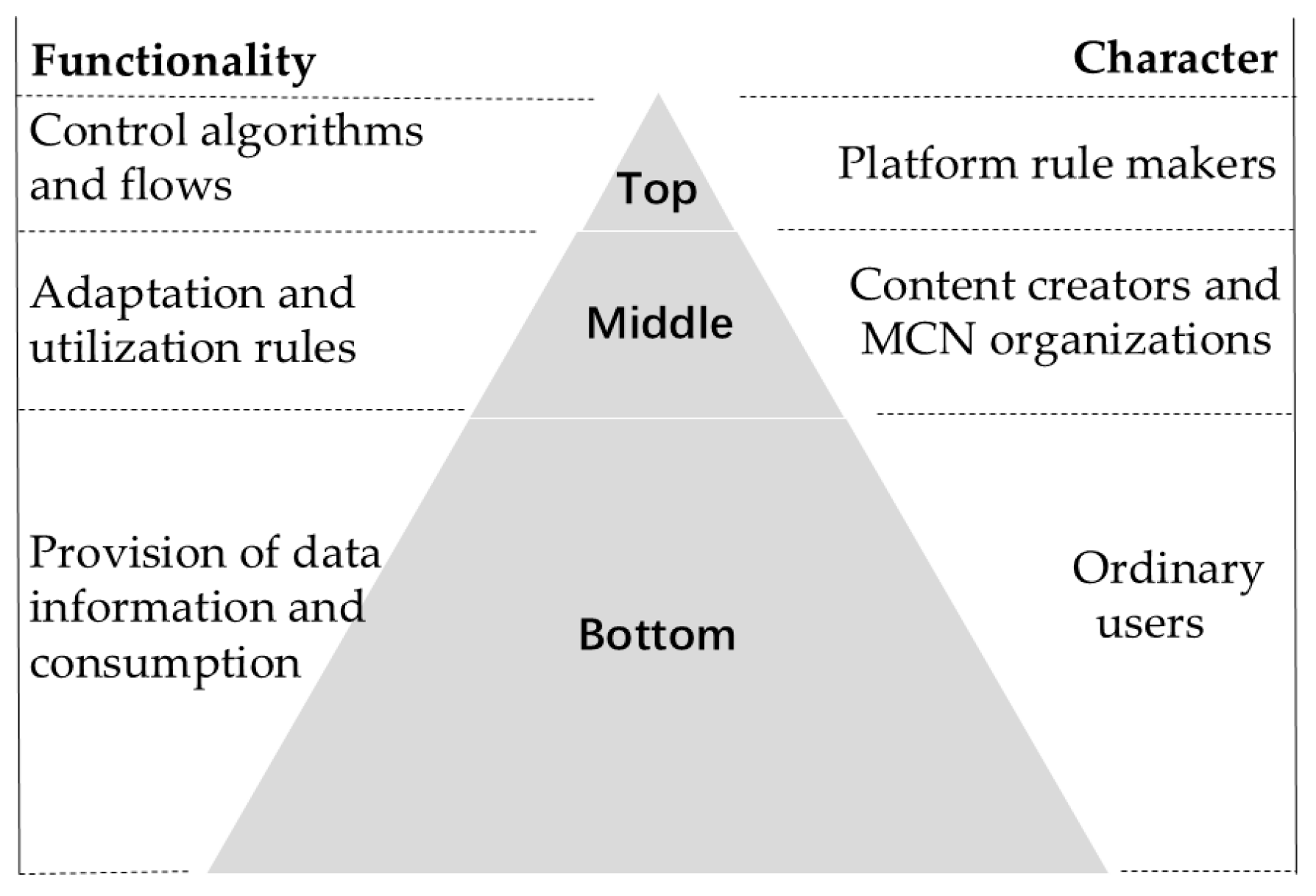

3.2. Role of Social Media in Stakeholder Engagement

- User-generated content (UGC) serves as the foundational fuel, enabling users to create and consume multimedia content (text, images, videos, audio) that sustains platform activity. Motivations for UGC production include social engagement (identity formation through audience interaction) and economic incentives (monetization via traffic sharing and advertising).

- Traffic allocation mechanisms act as centralized power nodes, prioritizing efficiency (promoting viral content), diversity (mitigating content monopoly), and commercial interests (advertisement integration).

- Algorithmic recommendation systems construct user profiles based on demographic data (age, gender, location) to deliver personalized content.

- User behavioral feedback (e.g., dwell time, likes, comments, shares, search queries) constitutes training data for algorithmic optimization.

3.3. Spatial Changes in Multi-Party Governance

4. Discussion

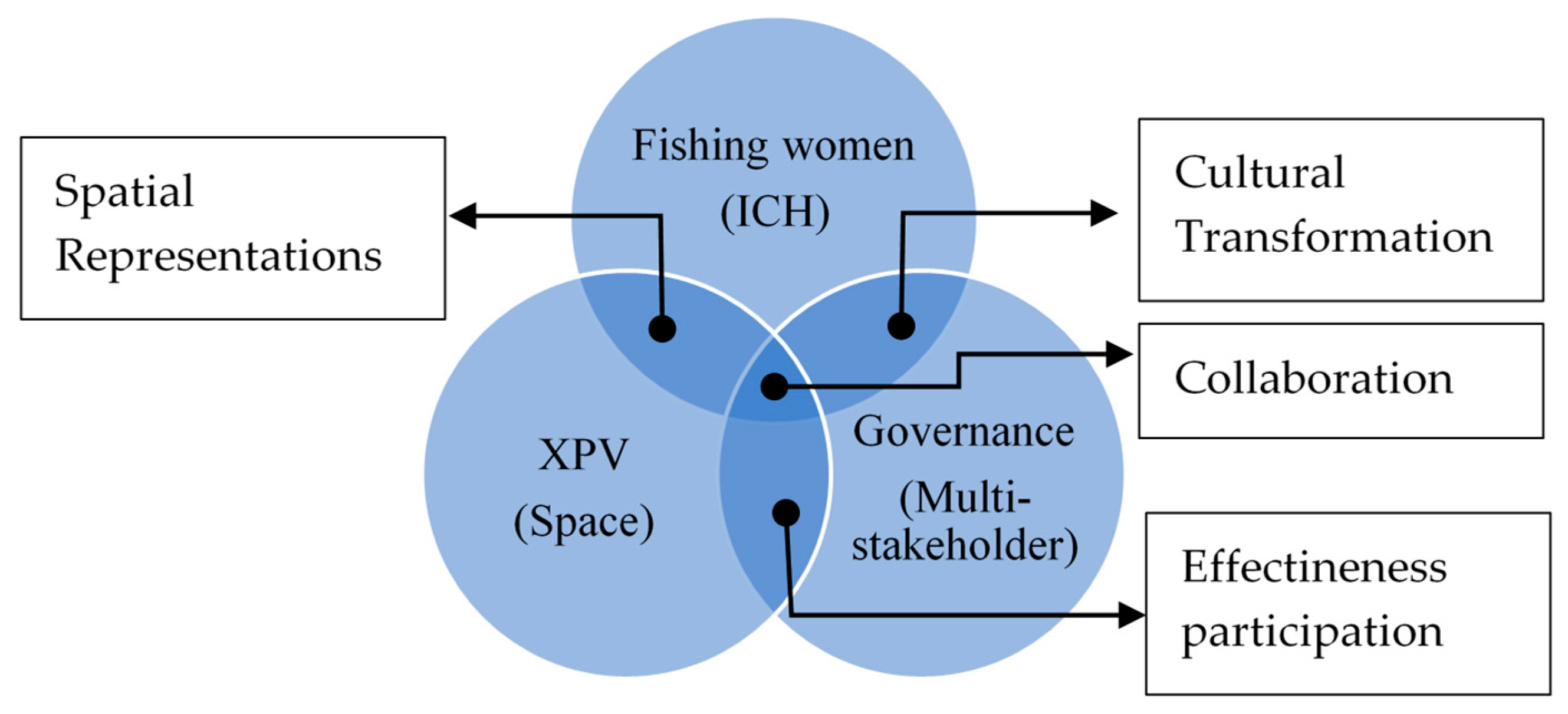

4.1. E-Participation Spatial Governance Model for Fishing Villages

4.2. The Social Network Jointly Constituted by Strong and Weak Ties

“Although many celebrities have engaged with ICH activities over the years, this sudden surge in popularity this year caught everyone by surprise. After seeing Zhao Liying’s photos, people from Beijing, Shanghai, and even overseas—such as Canada and the U.S.—have flown here to experience Zanhuawei. Some have even contacted us to purchase Zanhua materials for international shipping”.

4.3. The Relevance of Social Media and Its Operating Mechanisms to Spatial Governance in Fishing Villages

4.4. The Meaning of Social Media Participation

5. Conclusions

- Dissolution and re-creation of ICH. Social media expedites the infiltration of foreign cultures. Traditional customs are simplified into performative forms, traditional costumes evolve with new aesthetic trends, and the traditional cultural space is transformed into a tourist symbol and a space for virtual consumption. For instance, the popular Zanhuawei from XPV circulating on the Internet often deviates from the most traditional styles. Even though local residents may not endorse this new aesthetic, they still recommend these new Zanhuawei styles to customers to meet their demands.

- Community fragmentation and intergenerational conflicts. This is mainly manifested in the digital divide, which marginalizes the elderly from the decision-making process. While external forces such as fishermen, tourists, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) now have more direct access to participate in governance, it also brings challenges such as information distortion and unequal participation opportunities. The weakening of traditional clan authority has exacerbated the imbalances within the community’s power structure. Not all residents in XPV have embraced the tourism industry. There are still those who persist in their traditional livelihoods, such as prying oysters. They fail to comprehend the enthusiastic behavior of tourists and are unable to benefit from the booming tourism industry. Moreover, the occupation of fishing village spaces by foreign tourists and investors has undermined the spatial rights of some of the indigenous inhabitants.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vitruvius. De Architectura; Intellectual Property Publish: Beijing, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Li, B.; Jiang, W. State-led versus market-led: How institutional arrangements impact collaborative governance in participatory urban regeneration in China. Habitat Int. 2024, 150, 103134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanoff, H. Community Participation Methods in Design and Planning; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, J.; Heath, T. Community Participation of China’s Urban Regeneration: A Case Study of Sanxue Historical District in Xi’an. In Innovative Public Participation Practices for Sustainable Urban Regeneration; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Yang, L.; Ma, H. Community Participation Strategy for Sustainable Urban Regeneration in Xiamen, China. Land 2022, 11, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Ali, Z.M.; Hashim, N.H.N.; Ahmad, Y.; Wang, H. Evaluating social sustainability of urban regeneration in historic urban areas in China: The case of Xi’an. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Jia, L.; Wu, W.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y. Urbanization for rural sustainability—Rethinking China’s urbanization strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, P.; Chen, H.; Lai, M.; Zhao, S. The dynamics and driving mechanisms of rural revitalization in western China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shen, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, L. Where to revitalize, and how? A rural typology zoning for China. Land 2021, 10, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.; Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, D.; Qu, Y. Rural restructuring at village level under rapid urbanization in metropolitan suburbs of China and its implications for innovations in land use policy. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Zhang, T.; Jiao, Z.; Duan, Y.; Dewancker, B.J.; Gao, W. The impact of fishery industrial transformation on rural revitalization at village level: A case study of a Chinese fishing village. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2022, 227, 106277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Mohabir, N.; Ma, R.; Wu, L.; Chen, M. Whose village? Stakeholder interests in the urban renewal of Hubei old village in Shenzhen. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. A brief discussion on the landscape regeneration design of abandoned traditional villages: Taking the Boao Forum for Asia theme park as an example. Gard. Constr. Urban Plan. 2022, 4, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Hou, X.; Xu, H. Dynamic Expansion of Urban Land in China’s Coastal Zone since 2000. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Wu, T.; Hou, W.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yu, L. Characteristics of coastline changes in mainland China since the early 1940s. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2016, 59, 1791–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucińska, D.; Adinolfi, G.; Frigerio, I.; Gavinelli, D.; Zanolin, G.; Werner, W.; Rauscher, N.; Jaczewska, B.; Gręda, Ł. Case study in Poland: Understanding spatial diversity of social vulnerability to natural hazards based on local level assessments within the European Union. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 96, 103941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Tsai, S.-C. The Transformation of Coastal Governance, from Human Ecology to Local State, in the Jimei Peninsula, Xiamen, China. Water 2023, 15, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-Y.; Zou, Z.; Tsai, S.-C. From Fishing Village to Jimei School Village: Spatial Evolution of Human Ecology. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. Prot. 2022, 2, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabinyi, M. The role of land tenure in livelihood transitions from fishing to tourism. Marit. Stud. 2020, 19, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.; Chen, T.; Li, X. A new style of urbanization in China: Transformation of urban rural communities. Habitat Int. 2016, 55, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-R.; Chu, T.-J.; Lin, T.-S. Key Sustainable Factors for Recreational Fishery Development Under Rural Revitalization Policy. Int. J. 2022, 2, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, H. (Eds.) The Path Construction of the Evolution from Fishing Town to Leisure Island. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Conference on Sport Science, Education and Social Development (SSESD 2023), Qingdao, China, 28–30 July 2023; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 266–274. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, C.-H.; Wang, X.-R.; Lu, Y.-M.; Chu, T.-J. Assessing the Role of Policy in the Evolution of Recreational Fisheries in Chinese Fishing Villages: An Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Delphi Method Analysis. Fishes 2024, 9, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.-C.; Zhang, X.-F.; Lee, S.-H.; Wang, H. Urban Governance, Economic Transformation, and Land Use: A Case Study on the Jimei Peninsula, Xiamen, China, 1936–2023. Water 2024, 16, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, B. Fishing: How the Sea Fed Civilization; Gūsa Press; Walkers Cultural Enterprise Ltd.: New Taipei City, Taiwan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, D.; Mou, Q.; He, Y. The era textual research and cultural characteristics of Hainan fishermen’s Genglubu. J. South-Cent. Univ. Natl. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2016, 36, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R.; Yue, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jin, Z.; Peng, Q. Mode selection of modernization transformation of traditional fishing villages from the perspective of complex adaptive system. Oper. Manag. 2020, 1, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Han, X.-Y. Research on the relationship between fishermen’s social interaction and social transformation of fishing villages. Chin. Fish. Econ. 2007, 2, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sundström, A. Corruption and regulatory compliance: Experimental findings from South African small-scale fisheries. Mar. Policy 2012, 36, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, L. How Community Co-management is Possible—A Case Study of Offshore Fisheries Resource Governance in Meicun. Agric. Econ. Issues 2023, 12, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, W. New Research Progress on the Theory of Governing the Commons. Econ. News 2020, 11, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. National logic of modernizing the governance system. Soc. Sci. China 2019, 5, 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Fei, X.; Luo, L.; Kong, X.; Zhang, J. Social network analysis of heterogeneous subjects driving spatial commercialization of traditional villages: A case study of Tanka Fishing Village in Lingshui Li Autonomous county, China. Habitat Int. 2025, 155, 103235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näkki, P.; Bäck, A.; Ropponen, T.; Kronqvist, J.; Hintikka, K.A.; Harju, A.; Pöyhtäri, R.; Kola, P. Social Media for Citizen Participation: Report on the Somus Project; VTT Publications: Espoo, Finland, 2011; p. 755. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, G.C.; Rocha, M.C.F.; Poplin, A. (Eds.) E-Participation: Social media and the public space. In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications–ICCSA 2012: 12th International Conference, Salvador de Bahia, Brazil, 18–21 June 2012; Proceedings, Part I 12. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germnay, 2012; pp. 491–501. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.-M.; Wang, J.; Lee, S.-H.; Tsai, S.-C. How Traditional Fishing Villages Move towards Sustainable Management: A Case Study of Industrial Transformation and Multi-Party Governance Models. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J. “Placing” the relation of social media participation to neighborhood community connection. J. Urban Aff. 2020, 42, 1262–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Kant, S. Using social media for citizen participation: Contexts, empowerment, and inclusion. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effing, R.; Van Hillegersberg, J.; Huibers, T.W. (Eds.) Social media participation and local politics: A case study of the Enschede council in the Netherlands. In Proceedings of the Electronic Participation: 5th IFIP WG 8.5 International Conference, ePart 2013, Koblenz, Germany, 17–19 September 2013; Proceedings 5. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germnay, 2013; pp. 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Zhu, L. “Be a Xunpu Woman for one day”: How to Construct Collective lmagination by Shooting Short Video at an Internet Famous Site. Media Watch 2024, 2, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zheng, W. Research on the Development of the East Coast Sea Tourism Complex in Quanzhou Central City. J. Mudanjiang Univ. 2013, 22, 106–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Quanzhou: Emporium of the World in Song-Yuan China. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1561/ (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Quanzhou Municipal Natural Resources and Planning Bureau. Quanzhou City’s Quanpu Folk Culture Village Protection and Renovation Plan; Quanzhou Municipal Natural Resources and Planning Bureau: Quanzhou, China, 2013; Updated 2013/12/17. Available online: https://zyghj.quanzhou.gov.cn/xxgk/zdxxgk/ghcg/zxgh/201312/t20131217_2411074.htm (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- The State Council of the PRC. Notice of the State Council on Promulgation of the Second Batch of National Intangible Cultural Heritage List and the First Batch of National Intangible Cultural Heritage Expansion Project List. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2008-06/14/content_1016331.htm (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Chen, Z.; Hong, W. Research on Cultural Inheritance of Women’s Headdress in Xunpu. Reg. Cult. Study 2020, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; He, M.-M.; Tsai, S.-C. Revitalization or Alienation: Reflections on Continuation of Traditional Culture. Innov. Des. Cult. 2024, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lu, L. Probing the long-term evolution of traditional village tourism destinations from a glocalisation perspective: A case study of Wuzhen in Zhejiang province, China. Habitat Int. 2024, 148, 103073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H. Xunpu women’s “head garden”. Friends Sci. 2012, 5, 86–87. [Google Scholar]

- Custom of Xunpu Women; China Intangible Cultural Heritage Network; China Intangible Cultural Heritage Digital Museum: Suzhou, China; Available online: https://www.ihchina.cn/project_details/15235/ (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Ushering in the New Year “Off to a Good Start” the City’s New Year’s Day Holiday Main Tourism Economic Indicators Rise in Quantity and Quality; Quanzhou Cultural Tourism Bureau Quanmedia: Quanzhou, China. Available online: https://www.quanzhou.gov.cn/zfb/xxgk/zfxxgkzl/qzdt/qzyw/202401/t20240103_2989069.htm (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Provincial Government Circular Praise! One Place in Our City Was Selected; Fengze District Government Office: Quanzhou, China, 2024.

- Kapoor, K.K.; Tamilmani, K.; Rana, N.P.; Patil, P.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Nerur, S. Advances in Social Media Research: Past, Present and Future. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018, 20, 531–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medaglia, R. Measuring the diffusion of eParticipation: A survey on Italian local government. Inf. Polity 2007, 12, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.H.; Jing, M.J.; Zhu, Y. Social Media Interactive Circle Communication Patterns: Driving Force and Social Value—Analysis Based on Hot Social Events. Journal. Enthus. 2019, 6, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Social Network Building Operations Guide 2025. Available online: https://max.book118.com/html/2025/0104/6135204142011021.shtm (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Li, W.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, K.; Chen, H.; Zhao, S. The Evolution Model of and Factors Influencing Digital Villages: Evidence from Guangxi, China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Chen, M.; Gu, D. How digital village construction affects to the effectiveness of rural governance?—Research on the NCA and QCA methods. Cities 2025, 156, 105514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciolac, R.; Iancu, T.; Popescu, G.; Adamov, T.; Feher, A.; Stanciu, S. Smart Tourist Village—An Entrepreneurial Necessity for Maramures Rural Area. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvizi, A.; Lytras, M.D. It’s Not a Fad: Smart Cities and Smart Villages Research in European and Global Contexts. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, E.; Anderson, B.A.; Skerratt, S.; Farrington, J. A review of the rural-digital policy agenda from a community resilience perspective. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 54, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Z. From Attention to Circle: The Social Basis and Development Path of Traffic Production. J. Shandong Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.L. Gansu Tianshui spicy hot pot “out of the circle” tips. Cult. Ind. 2024, 31, 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Ruxin, W. The Integration of Traditional Costumes and Local Development in the Yellow River Basin—Taking Luoyang as an Example. Chem. Fiber Text. Technol. 2024, 53, 137–139. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder Of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H. Eu e-participation and its value review. J. Xuehai 2014, 1, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Gao, X. Negative Public Opinion, Government Response and Discourse Reconstruction—An Analysis Based on 1711 Social Media Cases. China Adm. 2021, 5, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.S. The Strength of Weak Ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.T. Native China; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Liang, Y. Special Trust and Universal Trust: The structure and characteristics of Chinese trust. Study Sociol. 2002, 17, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.H. Accurately grasping China’s rural revitalization strategy. China’s Rural. Econ. 2018, 4, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, J.; Jin, S.; He, C.; Qiu, H. Community Economy; China Machine Press: Beijing, China, 2015; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, R.M.; Fariss, C.J.; Jones, J.J.; Kramer, A.D.I.; Marlow, C.; Settle, J.E.; Fowler, J.H. A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization. Nature 2012, 489, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centola, D. An Experimental Study of Homophily in the Adoption of Health Behavior. Science 2011, 334, 1269–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Utz, S. The emotional responses of browsing Facebook: Happiness, envy, and the role of tie strength. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 52, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, K.; Stephen, A.T. Are Close Friends the Enemy? Online Social Networks, Self-Esteem, and Self-Control. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 40, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.Y.; Zhang, Y.X.; Lin, J.F. Beautiful! Xunpu Zanhuawei Hides the Most Tantalizing Spring Scenery in Quanzhou. Quanzhou Evening Newspaper. 2023. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/663540833_121124406 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Yang, Y. Formation mechanism and development path of community economy: From the perspective of strong and weak relationship. J. Shenzhen Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 41, 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Quanzhou Culture Radio; Television and Tourism Bureau. Quanzhou Culture, Radio, Television and Tourism Bureau Organization Functions Quanzhou Culture, Radio, Television and Tourism Bureau Official Website: cQuanzhou Culture, Radio, Television and Tourism Bureau. 2019. Available online: https://cbtb.quanzhou.gov.cn/zwgk/jgzn/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Qu, Z. Behind the microblogging hot search: Decoding the traffic business ecosystem. Int. Brand Watch. 2021, 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.H. “Qin Lang Lost His Homework” Farce Came to an End, in-Depth Reflection Can Not Stop Here. Beijing Youth Daily, bjyouth.ynet.com. 2024. Available online: https://www.xinhuanet.com/comments/20240415/5ef986e42291432a912da8723f42ae6c/c.html (accessed on 16 April 2025).

| Categorization | Operator | Shop Source | Opening Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native | Outsider | Tenancy | Own House | Before 2023 | 2023–2024 | After 2024 | |

| Number of shops | 31 | 19 | 29 | 21 | 4 | 39 | 7 |

| Subtotal | 50 | 50 | 50 | ||||

| Post | Average Price | Quantity of Shops | Off-Peak Season Daily Average Number of People | Peak Season Daily Average Number of People | Off-Peak Season Daily Turnover/USD | Peak Season Daily Turnover/USD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zanhua | 5.54 | 246 | 65 | 200 | 88,584.6 | 272,568 |

| Makeup | 20.77 | 246 | 65 | 200 | 332,112.3 | 1,021,884 |

| Photography | 27.70 | 246 | 65 | 200 | 442,923 | 1,362,840 |

| Sum | 863,619.9 | 2,657,292 |

| Governing Body | Intermediary | Governance Mechanisms | Spatial Feature | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clan elders | Offline focus | Bloodline authority, township rules, customs and practices | Living space | Village, Mazu Temple, clan hall, etc. |

| Cooperative | Economic self-reliance, market regulation, laws and regulations | Production space | Tidal zone, fishing harbors, fishing grounds, etc. | |

| Government | Macro-control by central government, policy formulation by local government, administrative implementation by grass-roots government | Ecological space | Marine resources, intangible cultural resources, etc. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; He, M.-M.; Lee, S.-H.; Tsai, S.-C. Meaningful Multi-Stakeholder Participation via Social Media in Coastal Fishing Village Spatial Planning and Governance. Water 2025, 17, 1703. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17111703

Wang J, He M-M, Lee S-H, Tsai S-C. Meaningful Multi-Stakeholder Participation via Social Media in Coastal Fishing Village Spatial Planning and Governance. Water. 2025; 17(11):1703. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17111703

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jing, Ming-Ming He, Su-Hsin Lee, and Shu-Chen Tsai. 2025. "Meaningful Multi-Stakeholder Participation via Social Media in Coastal Fishing Village Spatial Planning and Governance" Water 17, no. 11: 1703. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17111703

APA StyleWang, J., He, M.-M., Lee, S.-H., & Tsai, S.-C. (2025). Meaningful Multi-Stakeholder Participation via Social Media in Coastal Fishing Village Spatial Planning and Governance. Water, 17(11), 1703. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17111703