Identifying the Layout of Retrofitted Rainwater Harvesting Systems with Passive Release for the Dual Purposes of Water Supply and Stormwater Management in Northern Taiwan

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What type of passive discharge outlet is most suitable for retrofitted conv. RWHSs?

- What size of passive discharge outlet is required to handle the designed storm and ensure consistency in selecting design events [39]?

- Where should the passive discharge outlet be located to accommodate the detention volume, and what operational strategy should be adopted to maintain long-term efficiency in both water supply and stormwater management?

2. Methodology

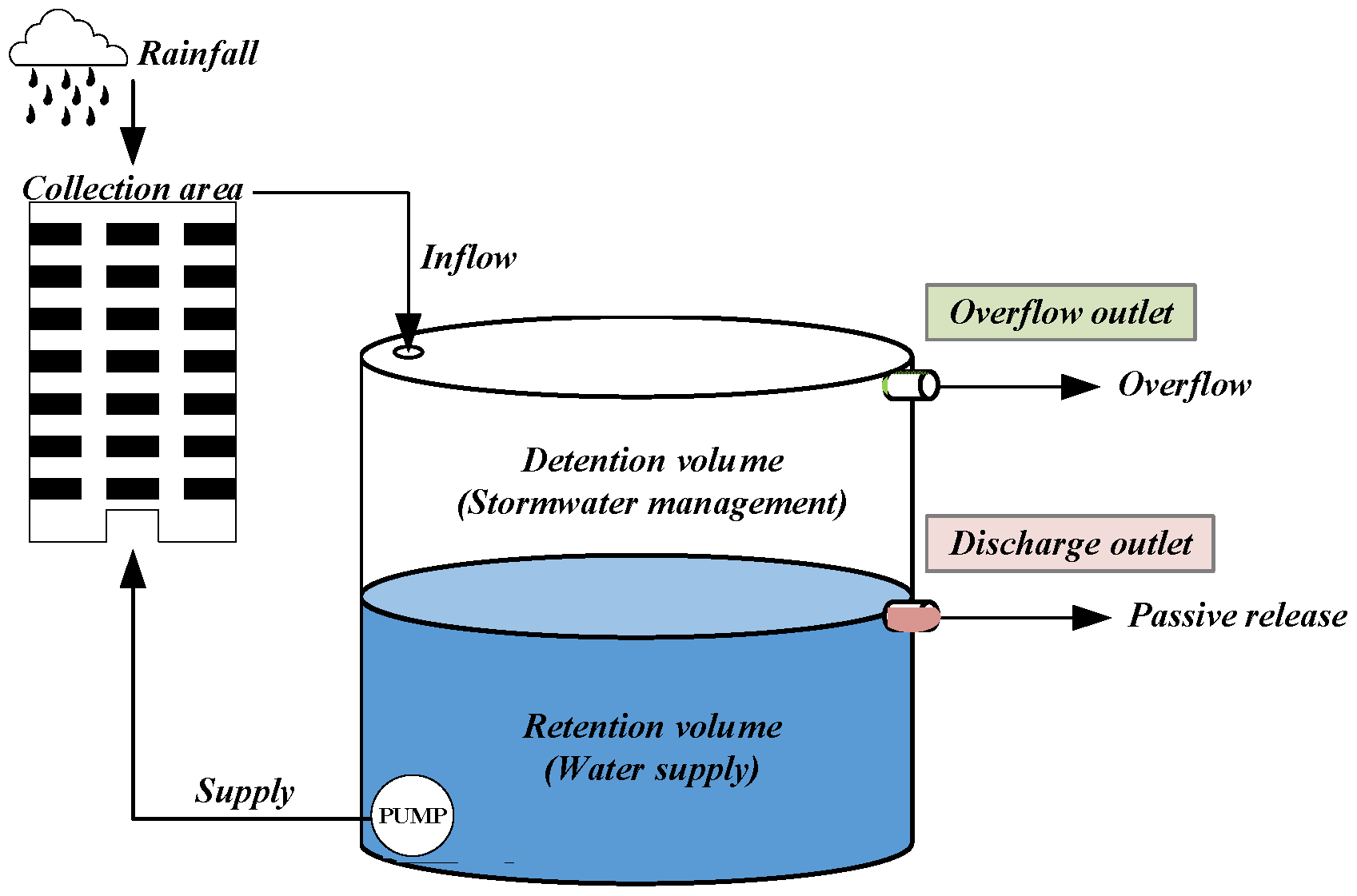

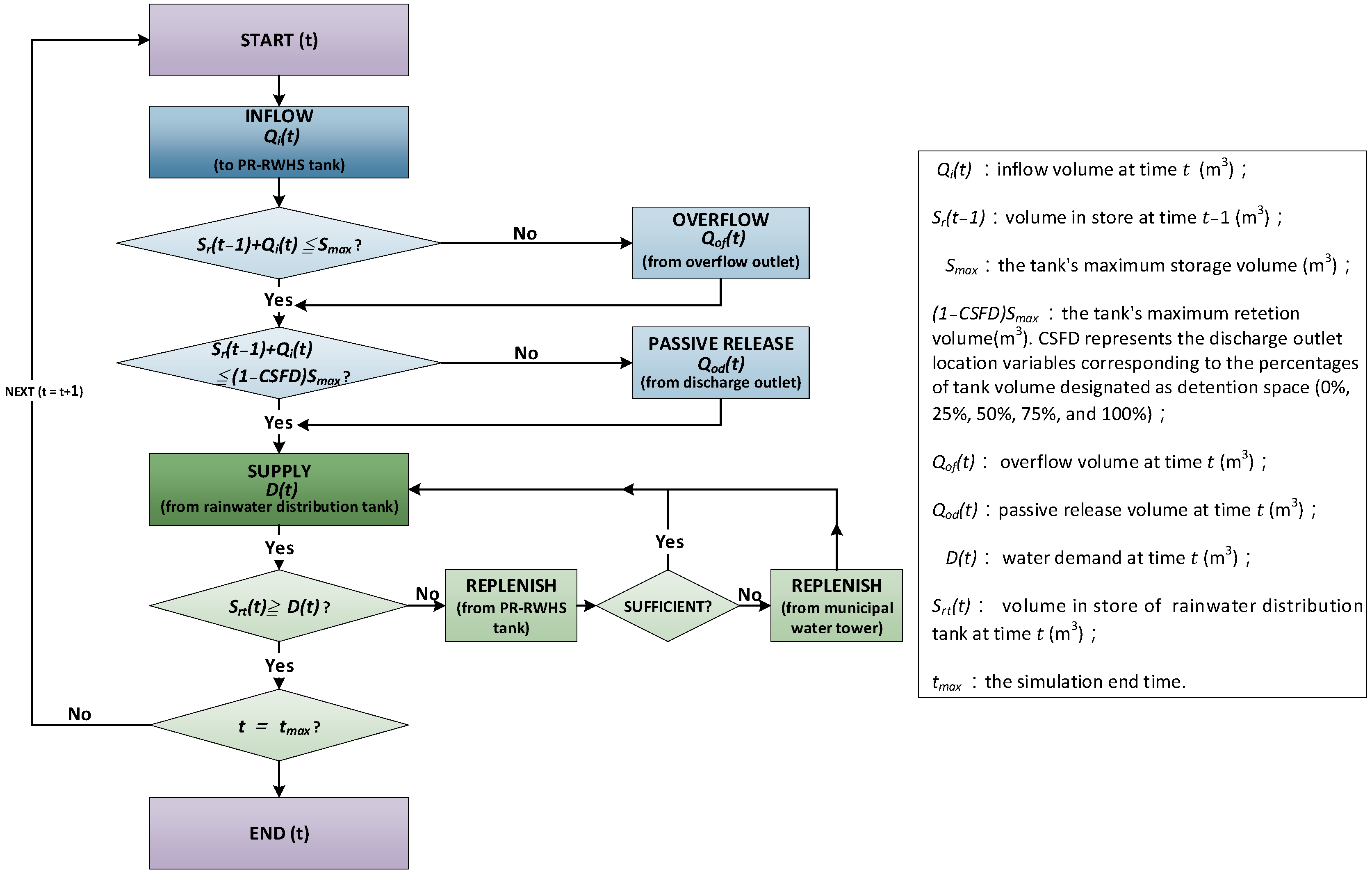

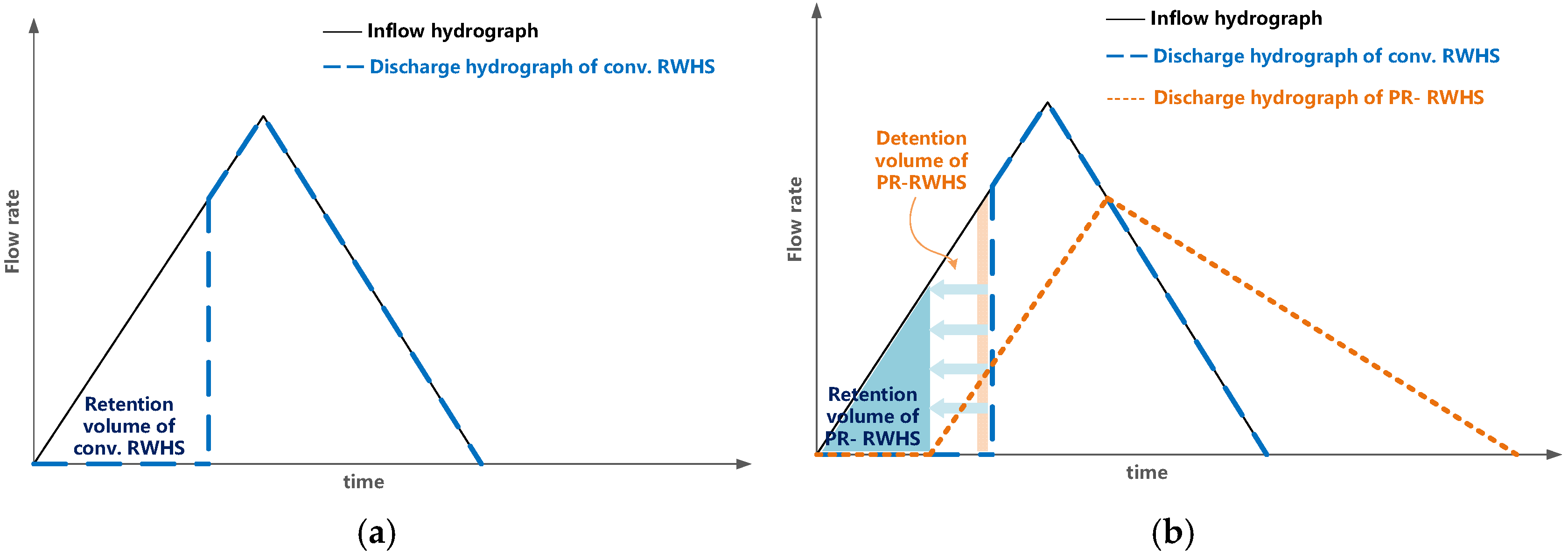

2.1. System Configurations of RWHSs with Passive Release Mechanisms

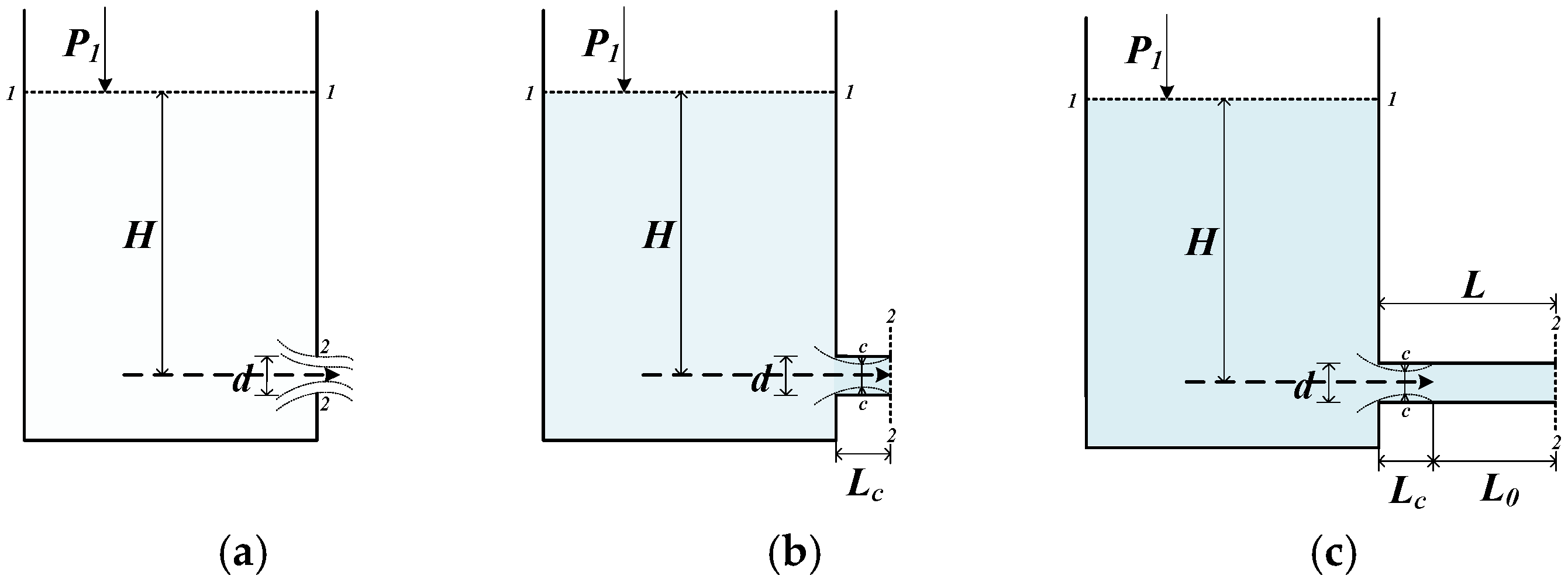

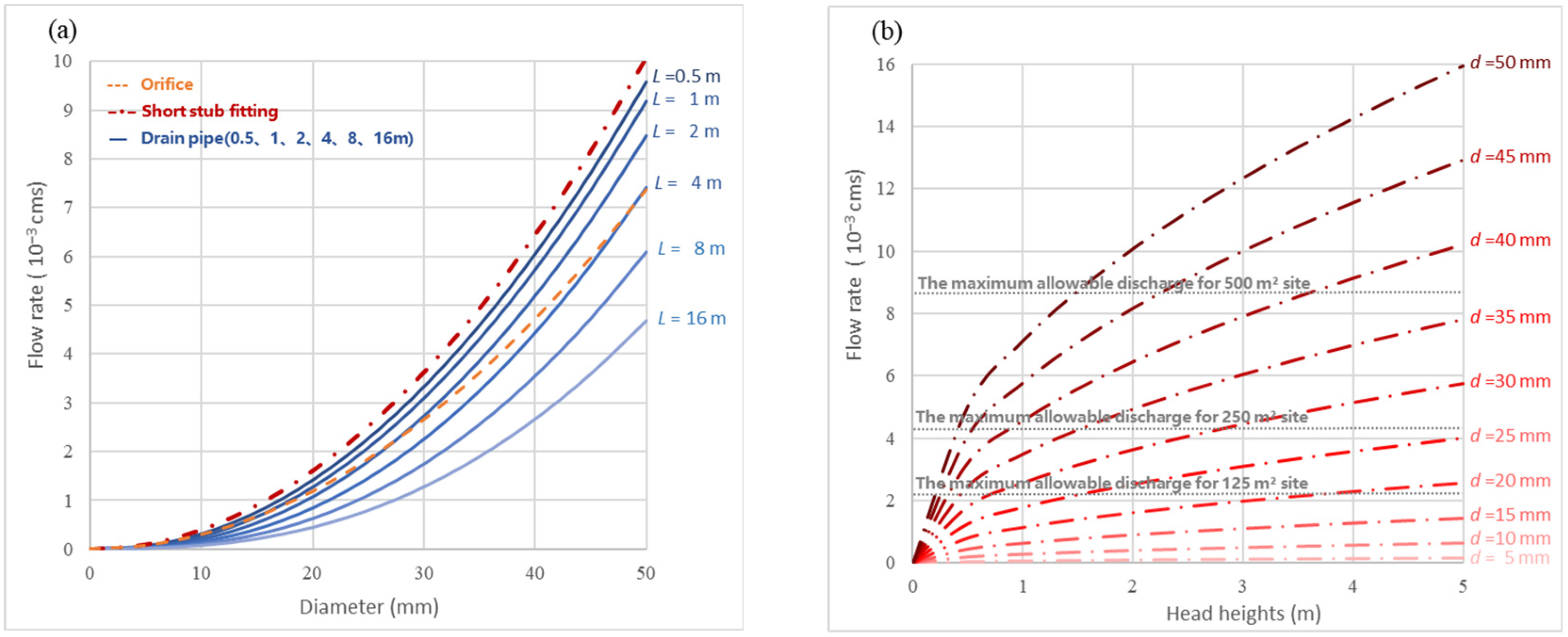

2.2. Types of Discharge Outlet

- Orifice: Shown in Figure 2a, this type is simple and cost-effective but can suffer from pressure losses due to fluid contraction at the orifice.

- Short Stub Fitting: Depicted in Figure 2b, this type involves drilling an orifice in the wall and adding a short discharge fitting. This design extends the drainage distance, (approximately 3 to 4 times the orifice diameter), reducing the impact of flow area contraction and thus improving drainage efficiency.

- Drainage Pipe: As illustrated in Figure 2c, this type connects a pipe to the short stub fitting, allowing for greater flexibility in the final discharge location. However, this configuration may result in additional head losses due to the pipe length and friction.

- Orifice

- 2.

- Short Stub Fitting

- 3.

- Drainage Pipe

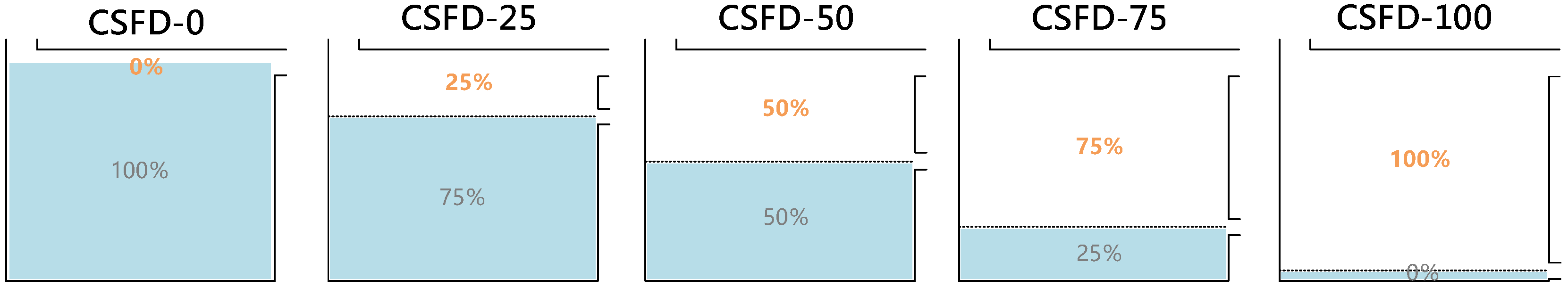

2.3. Location of the Discharge Outlet

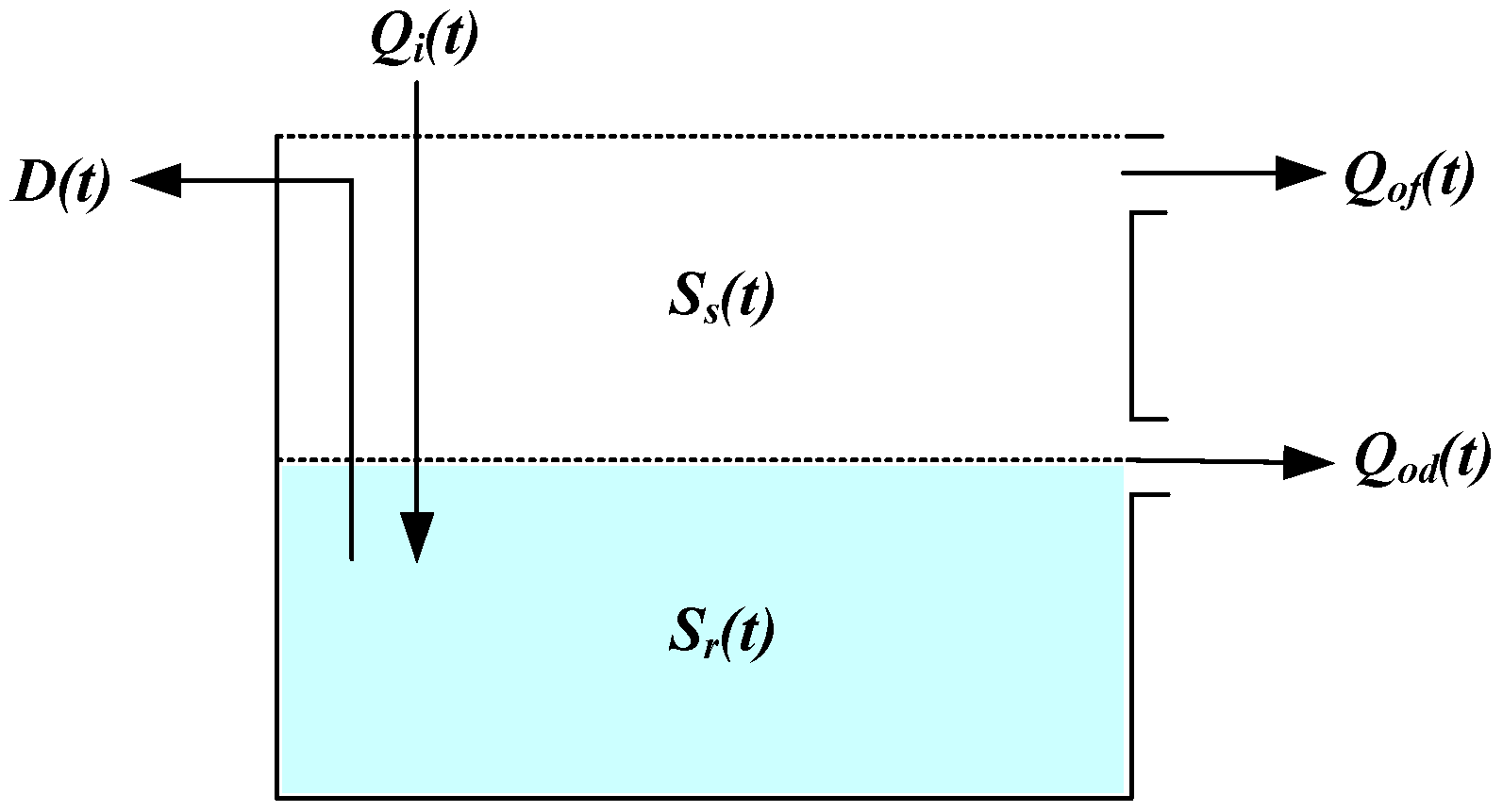

2.4. Model Description

- Peak Flow Mitigation Rate ()

- 2.

- Peak Flow Lag Time ()

- 3.

- Water Supply Reliability ()

2.5. Representative Buildings for Analysis

2.5.1. Classification of Building Types

2.5.2. RWHS Tank Volume Design

2.6. Climate Data

2.6.1. Design Storms

- 2-year return period: a = 2339.700, b = 25.905, c = 0.798;

- 5-year return period: a = 2250.161, b = 28.309, c = 0.731;

- 10-year return period: a = 1942.806, b = 28.556, c = 0.674.

2.6.2. Probably Hazardous Rainfall Events

2.7. Determination of Location of Discharge Outlet

- Scenario 1: The conv. RWHS operated year-round.

- Scenario 2: The discharge outlet of the PR-RWHS was open year-round.

- Scenario 3: The discharge outlet of the PR-RWHS was open during the wet season and closed during the dry season, provided the discharge outlet was equipped with valves.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Selection of Discharge Outlet Type

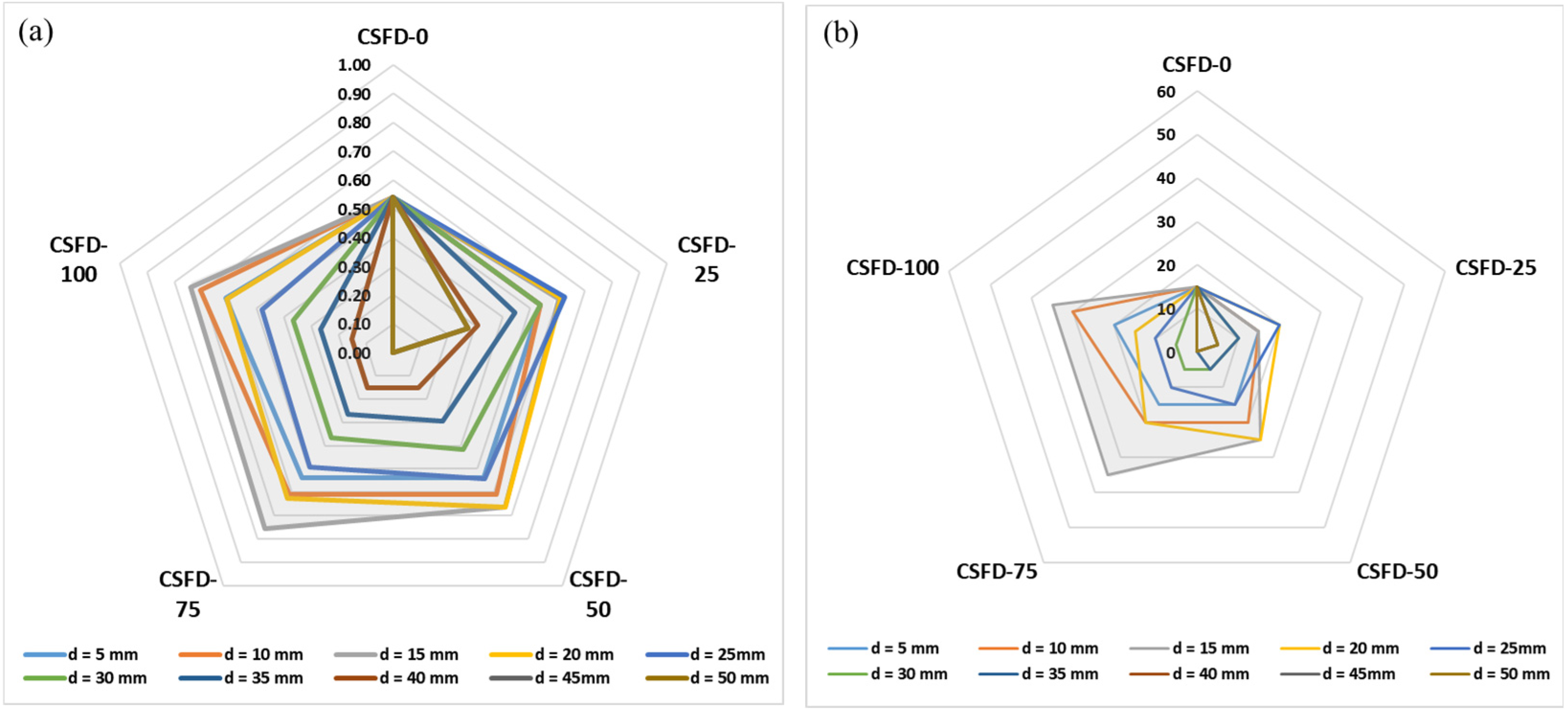

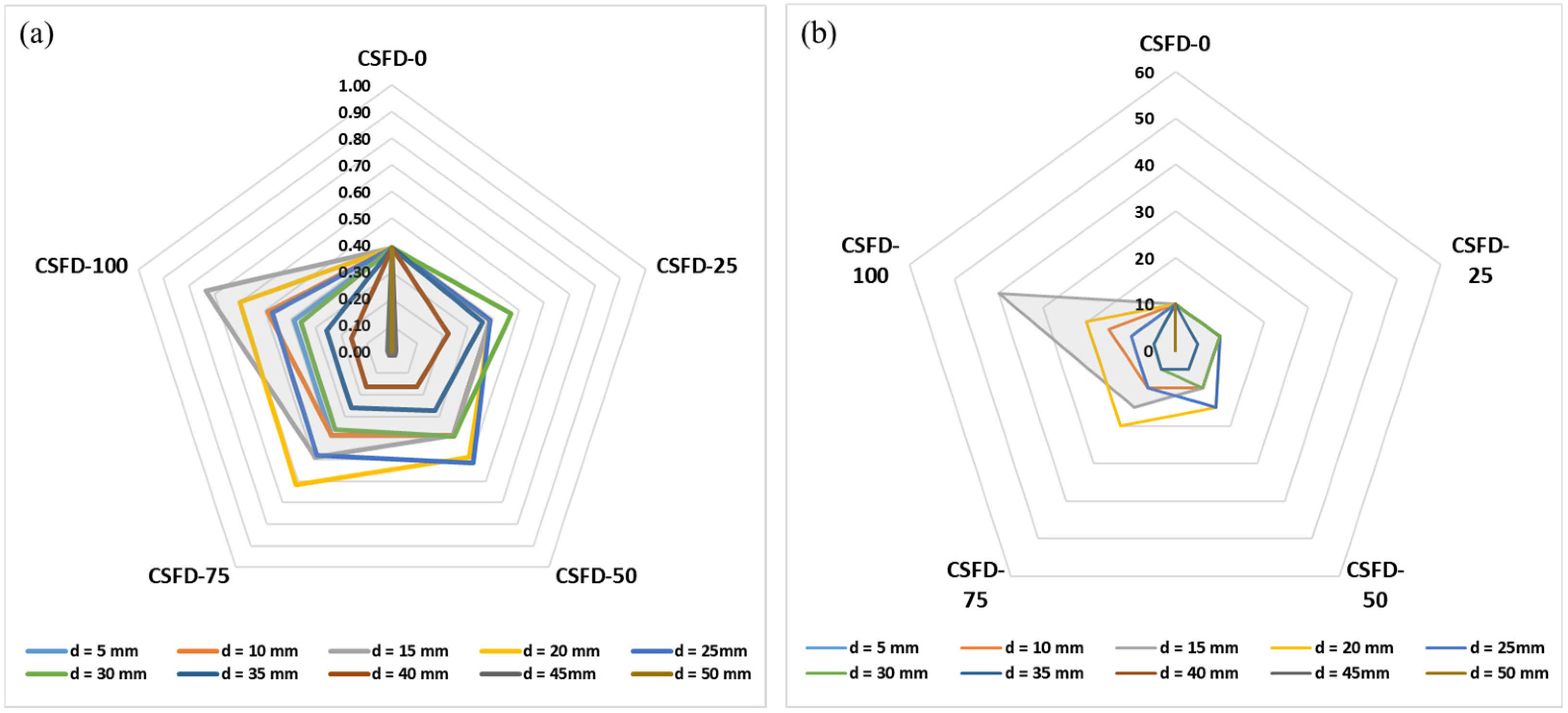

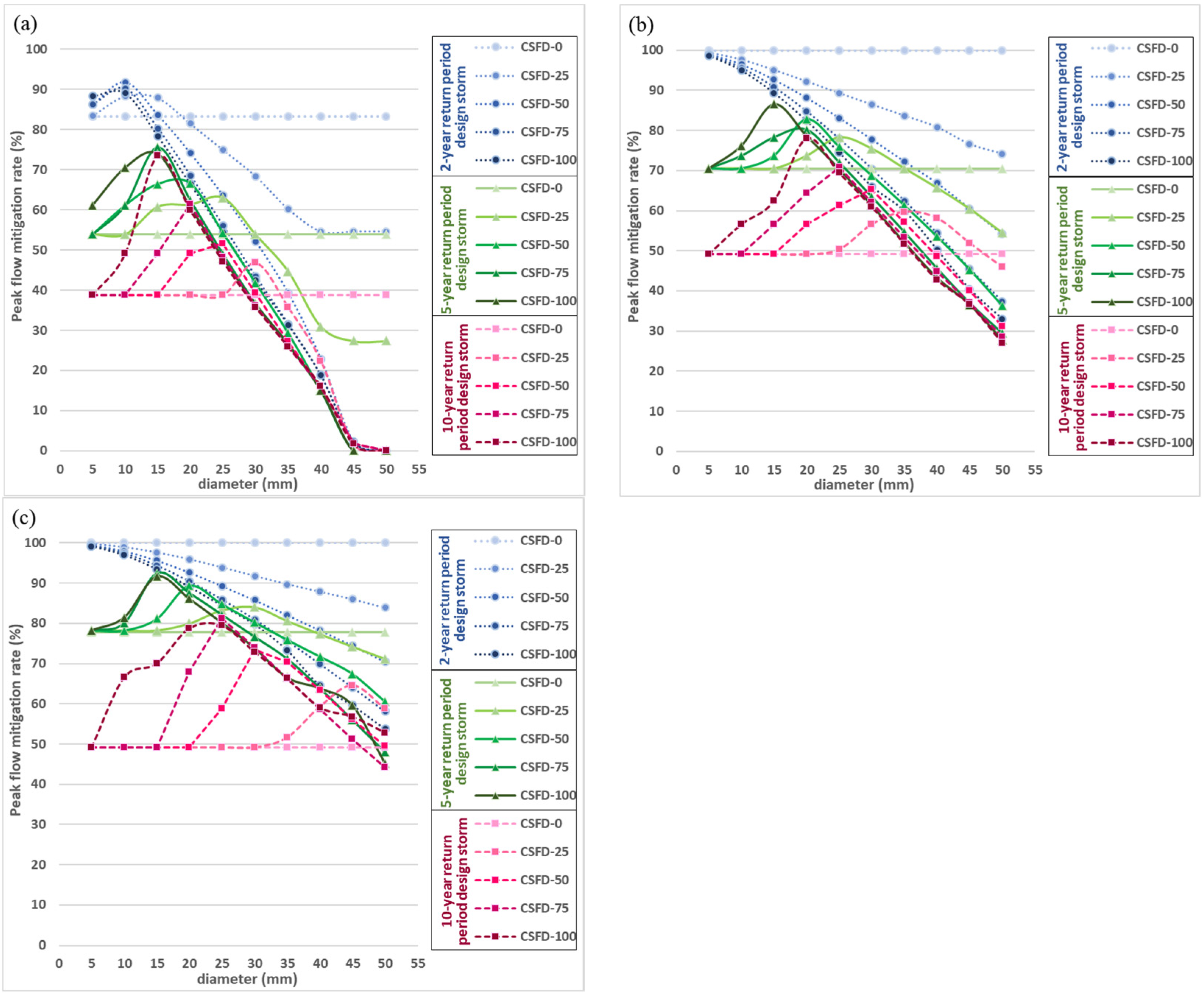

3.2. Determination of Discharge Outlet Size Using Design Storm

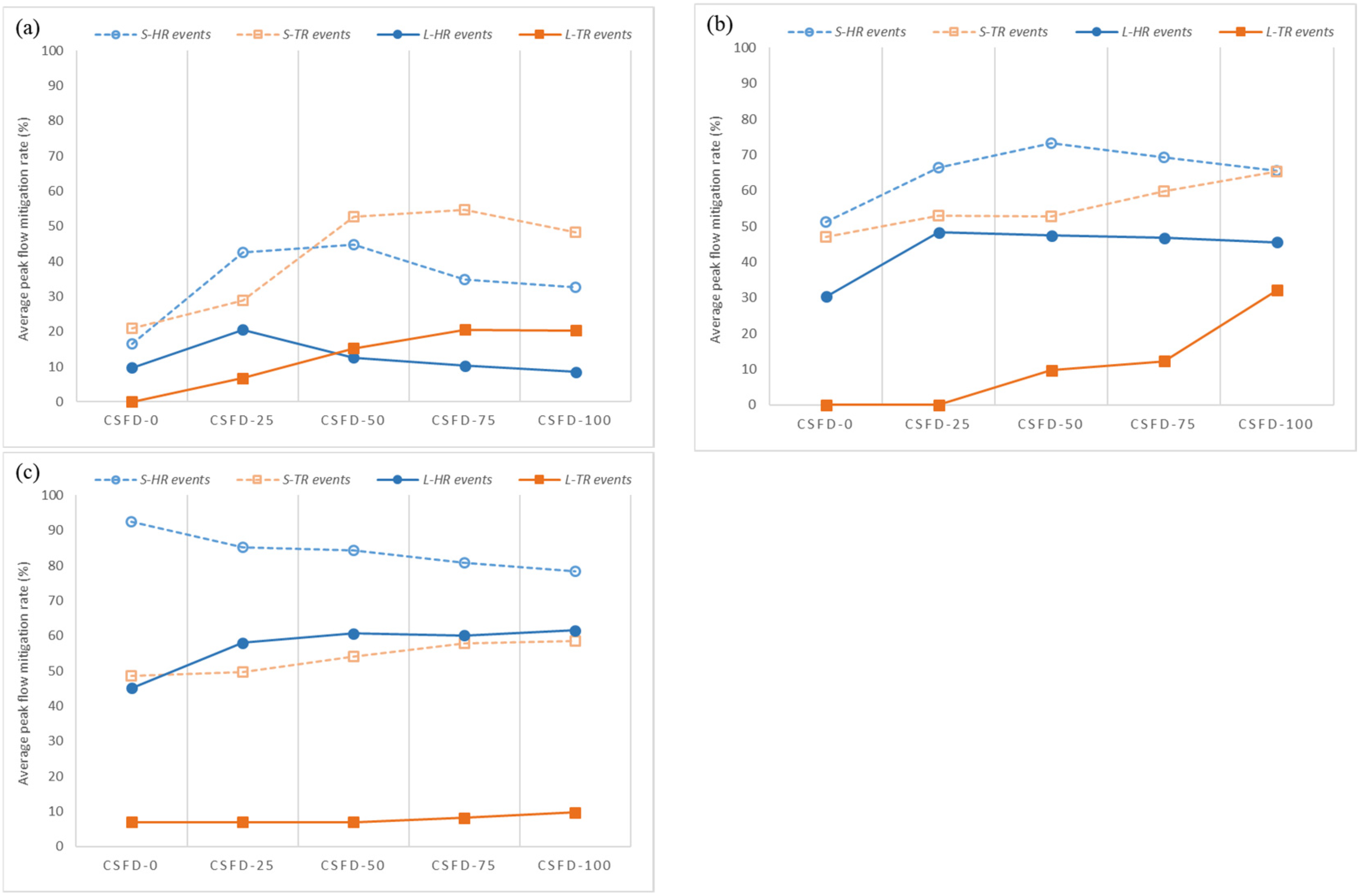

3.3. Validation of Discharge Outlet Diameter Using Probably Hazardous Rainfall Events

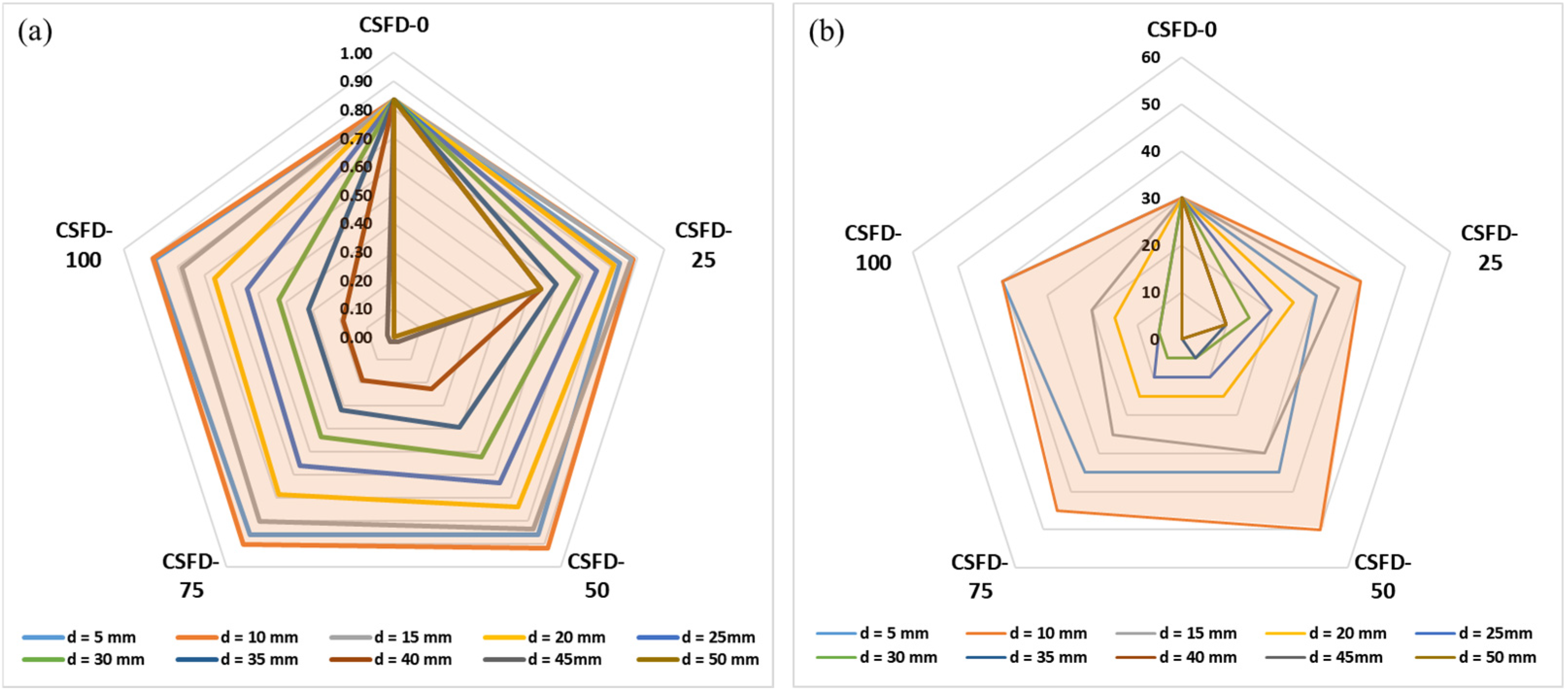

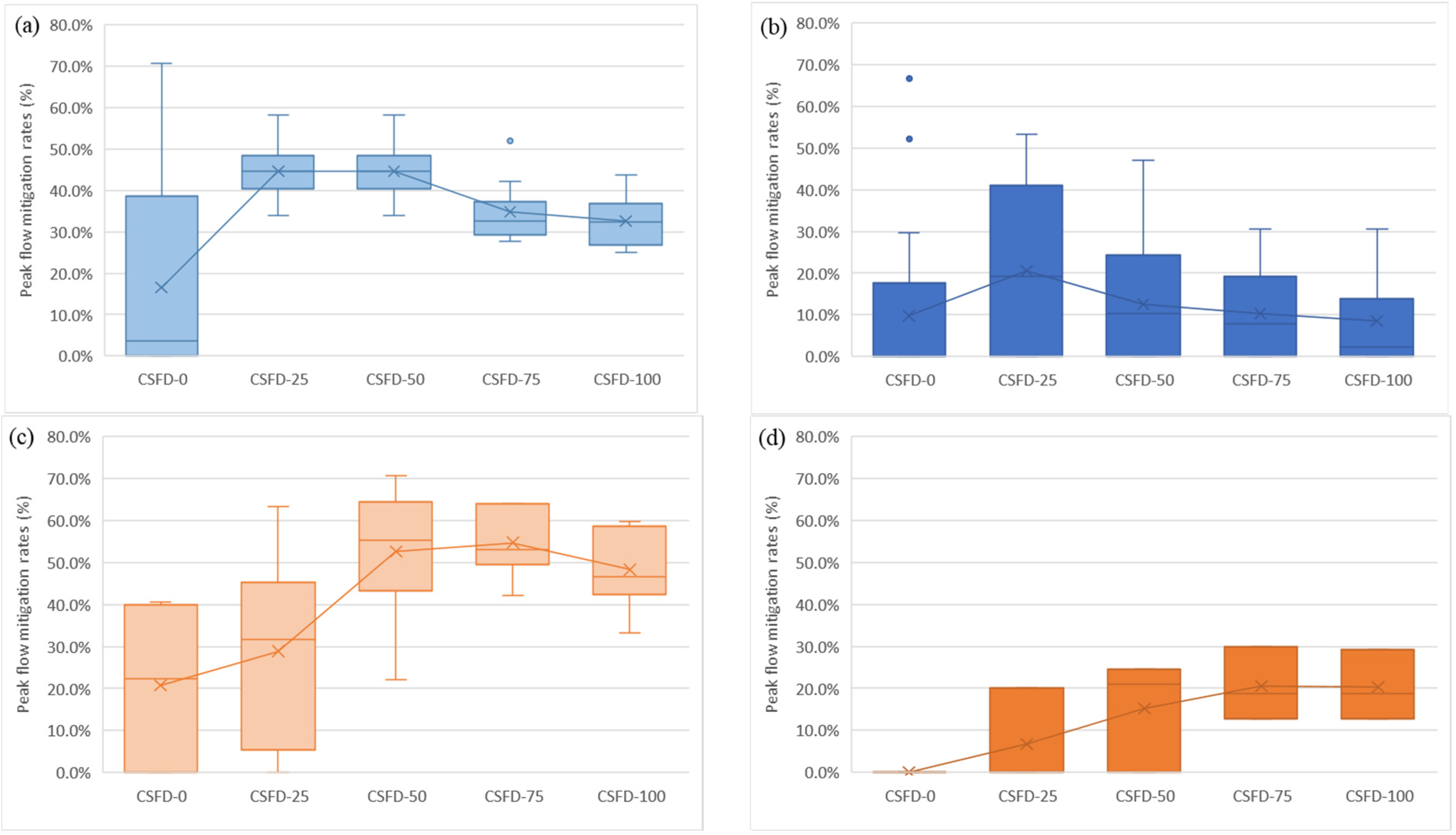

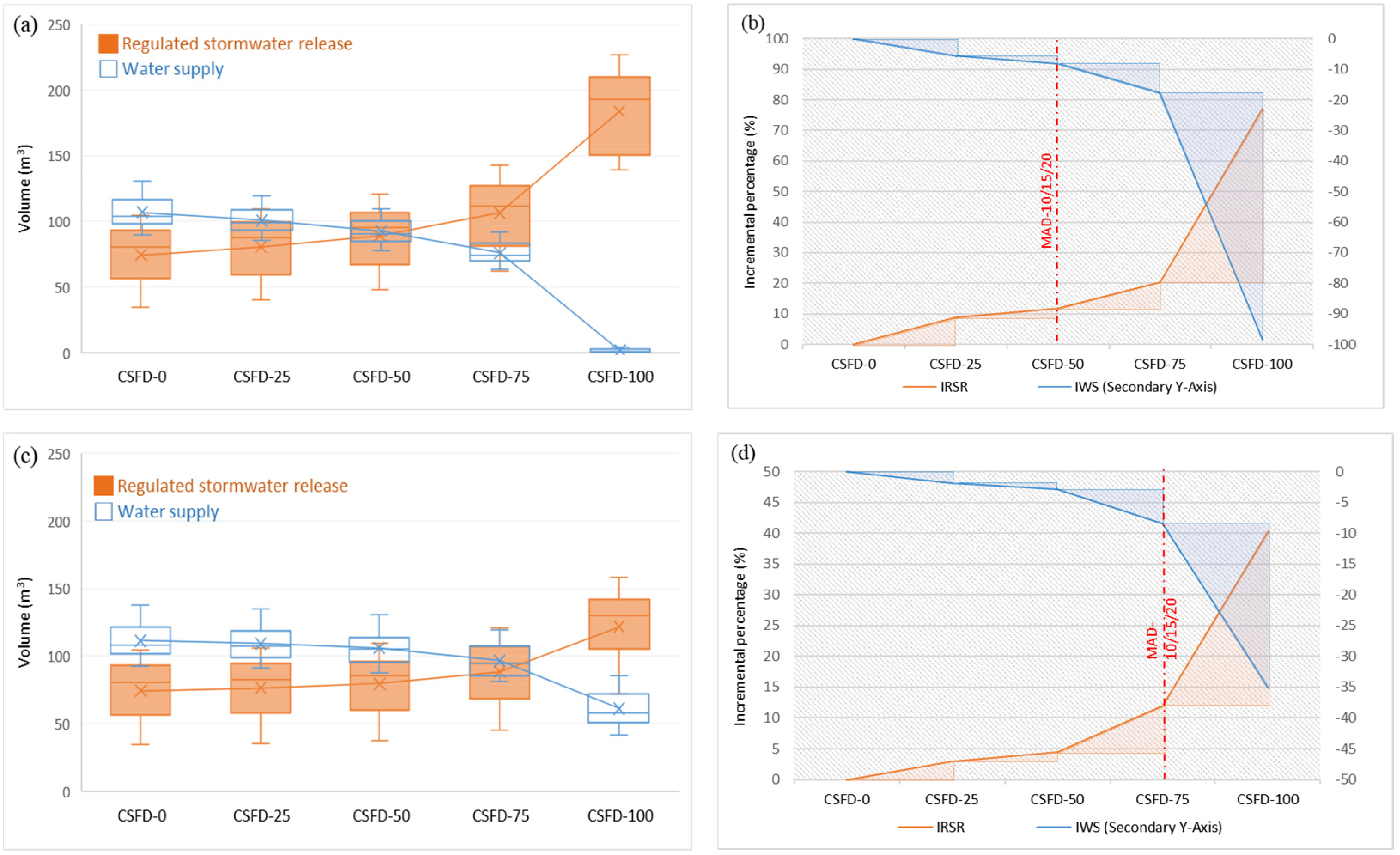

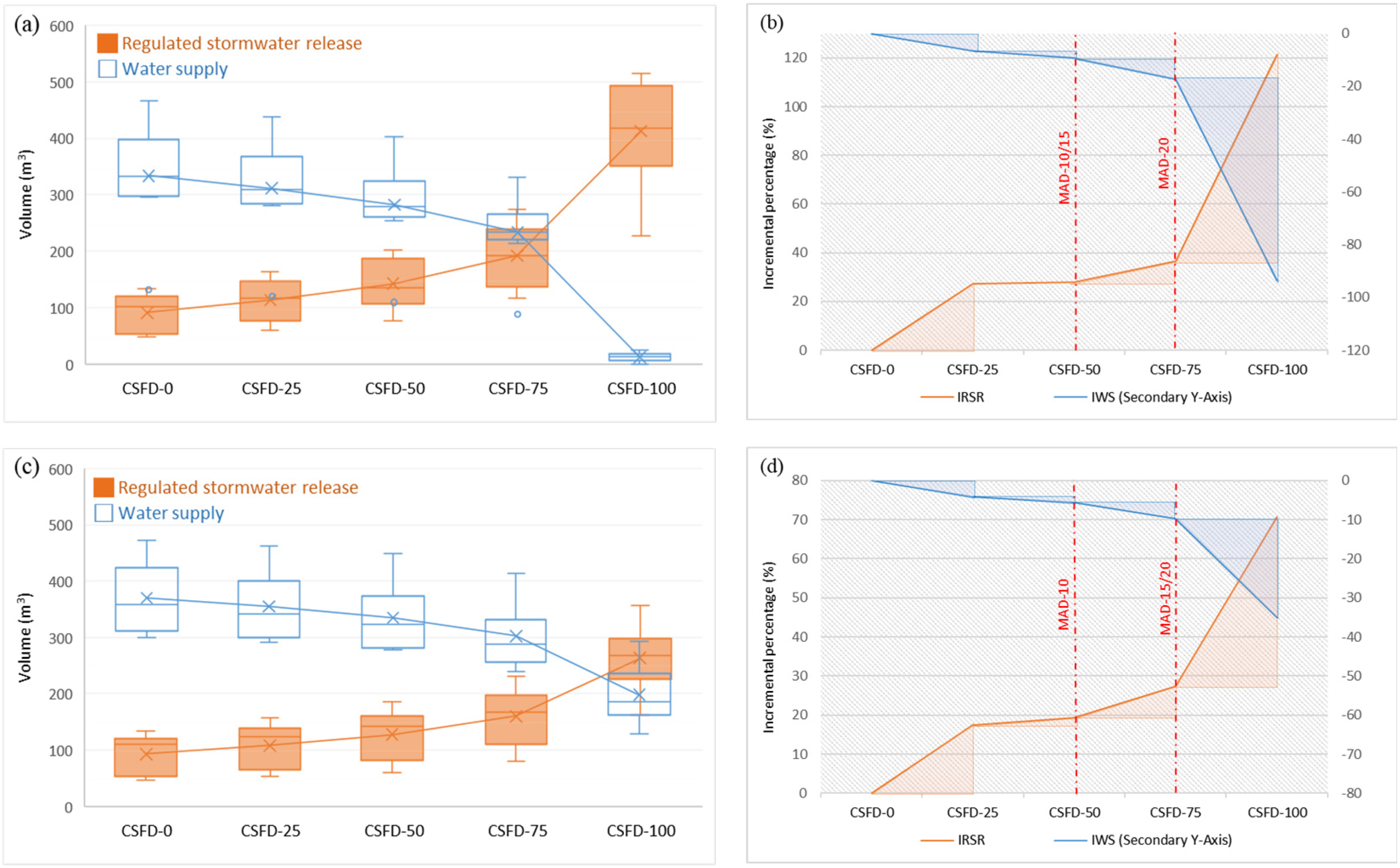

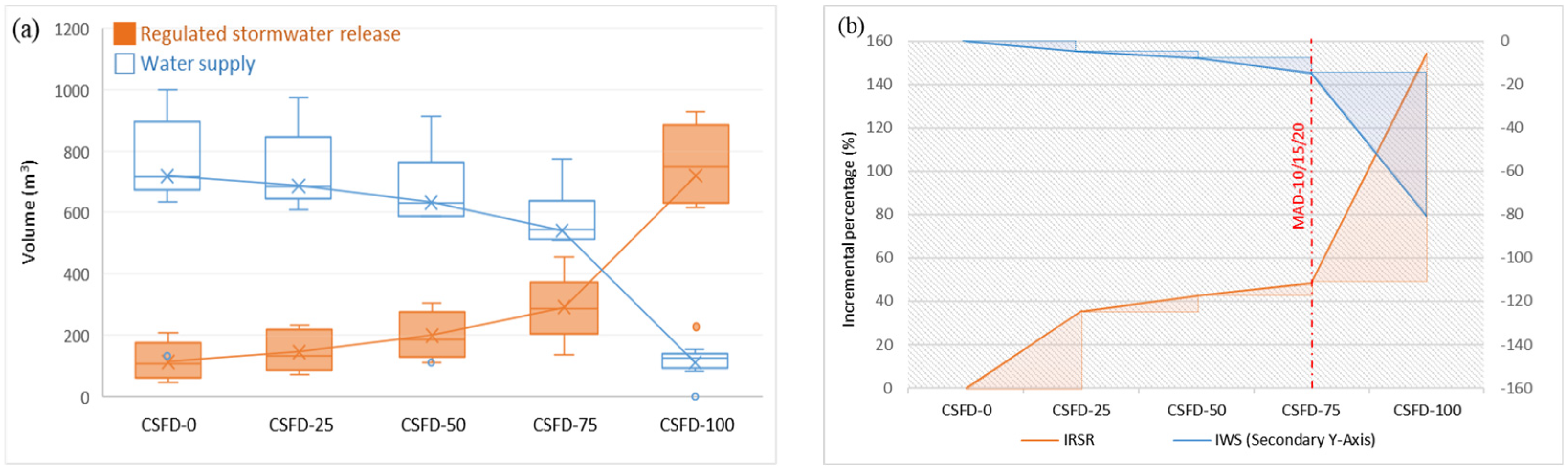

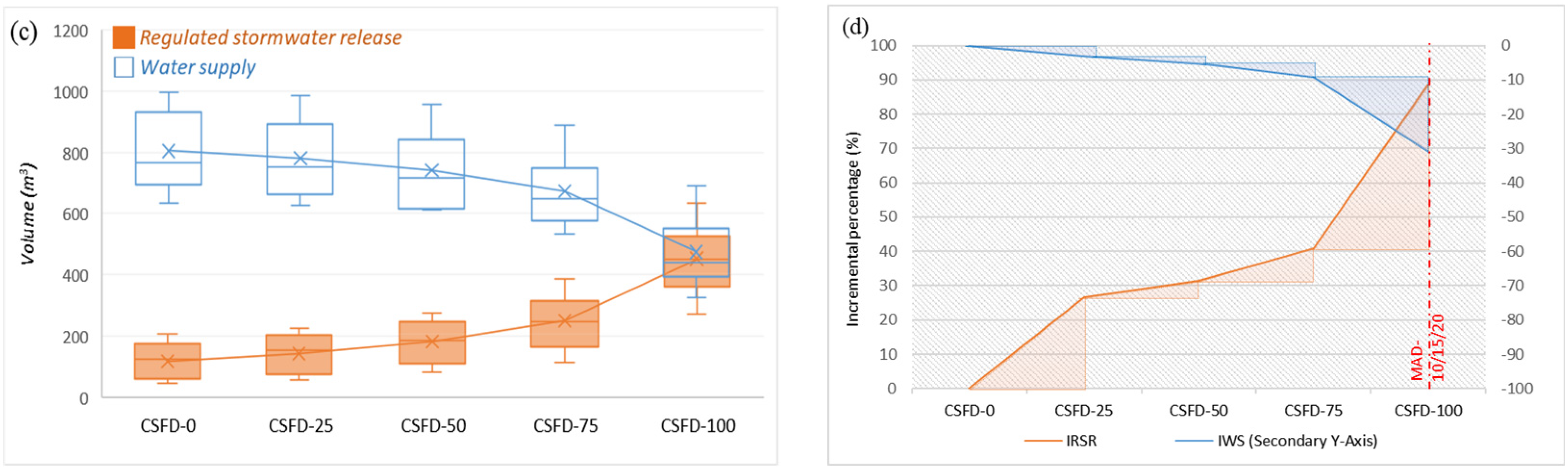

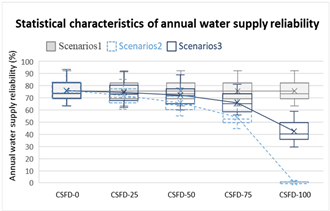

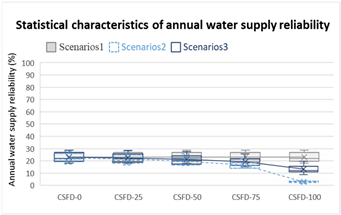

3.4. Determination of the Location of Discharge Outlets Using Continuous Rainfall Data

- Representative DH Building

- 2.

- Representative FSB

- 3.

- Representative ESB

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Water Resources Bureau. Current Status and Future Development of Water Resources in Taiwan; Ministry of Economic Affairs: Taipei, Taiwan, 2020. (In Chinese)

- Architecture and Building Research Institute. Green Buildings Evaluation Manual (GBEM)-Basic Version; Ministry of Interior: Taipei, Taiwan, 2023. (In Chinese)

- Architecture and Building Research Institute. Rainwater Harvesting Systems Design Manual for Green Buildings; Ministry of Interior: Taipei, Taiwan, 2021. (In Chinese)

- Water Resources Bureau. Rainwater Harvesting Systems Design and Construction Guideline–School Campus; Ministry of Economic Affairs: Taipei, Taiwan, 2022. (In Chinese)

- Water Resources Bureau. Runoff Allocation and Outflow Control Technical Design Manual; Ministry of Economic Affairs: Taipei, Taiwan, 2021. (In Chinese)

- Campisano, A.; Butler, D.; Ward, S.; Burns, M.J.; Friedler, E.; DeBusk, K.; Fisher-Jeffes, L.N.; Ghisi, E.; Rahman, A.; Furumai, H.; et al. Urban rainwater harvesting systems: Research, implementation and future perspectives. Water Res. 2017, 115, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorw, T.L.; Rodak, C.M.; Vogel, J.R.; Ahmed, F. Urban stormwater characterization, control and treatment. Water Environ. Res. 2018, 90, 1821–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alex Forasté, P.E.J.; Hirschman, D. A methodology for using rainwater harvesting as a stormwater management BMP. In Proceedings of the Low Impact Development International Conference (LID), San Francisco, CA, USA, 11–14 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, T.H.F. An Overview of Water Sensitive Urban Design Practices in Australia. Water Pract. Technol. 2006, 1, wpt2006018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Doménech, I.; Anta, J.; Perales-Momparler, S.; Rodriguez-Hernandez, J. Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems in Spain: A Diagnosis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.N.; Li, J.W.; Ma, Q. Integrating green infrastructure, ecosystem services and nature-basedsolutions for urban sustainability: A comprehensive literature review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 98, 104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, C.H.; Chiang, Y.C. Framework for assessing the rainwater harvesting potential of residential buildings at a national level as an alternative water resource for domestic water supply in Taiwan. Water 2014, 6, 3224–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słyś, D.; Stec, A. Centralized or decentralized rainwater harvesting systems: A case study. Resources 2020, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjaiang, P.; Limphitakphong, N.; Kanchanapiya, P.; Tantisattayakul, T.; Chavalparit, O. Assessing potential of rainwater harvesting: Case study building in Bangkok. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2018, 9, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alkan, M.O.; Hepcan, S. Determination of rainwater harvesting potential: A case study from Ege University. Adü Ziraat Derg. 2022, 19, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hari, D. Estimation of rooftop rainwater harvesting potential using applications of Google Earth Pro and GIS. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. (IJITEE) 2019, 8, 1122–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adugna, D.; Jensen, M.B.; Lemma, B.; Gebrie, G.S. Assessing the potential for rooftop rainwater harvesting from large public institutions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maqsoom, A.; Aslam, B.; Ismail, S.; Thaheem, M.J.; Ullah, F.; Zahoor, H.; Musarat, M.A.; Vatin, N.I. Assessing rainwater harvesting potential in urban areas: A building information modelling (BIM) approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umapathi, S.; Pezzaniti, D.; Beecham, S.; Whaley, D.; Sharma, A. Sizing of domestic rainwater harvesting systems using economic performance indicators to support water supply systems. Water 2019, 11, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, C.O.; Solyalı, O.; Akıntŭg, B. Optimal sizing of storage tanks in domestic rainwater harvesting systems: A linear programming approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 104, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, C.H.; Chiang, Y.C. Dimensionless analysis for designing domestic rainwater harvesting systems at the regional level in northern Taiwan. Water 2014, 6, 3913–3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Furumai, H. Assessment of rainwater availability by building type and water use through GIS-based scenario analysis. Water Resour. Manag. 2012, 26, 1499–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, M.J.; Fletcher, T.D.; Duncan, H.P.; Hatt, B.E.; Ladson, A.R.; Walsh, C.J. The performance of rainwater tanks for stormwater retention and water supply at the household scale: An empirical study. Hydrol. Process. 2015, 29, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abenayake, C.C.; De Silva, K.I.U.T.; Mahanama, P.K.S. Rainwater harvesting innovations for flood-resilient cities. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2020, 9, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gerolin, A.; Kellagher, R.B.; Faram, M.G. Rainwater harvesting systems for stormwater management: Feasibility and sizing considerations for the UK. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Sustainable Techniques and Strategies in Urban Water Management, Lyon, France, 27 June–1 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Freni, G.; Liuzzo, L. Effectiveness of rainwater harvesting systems for flood reduction in residential urban areas. Water 2019, 11, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBusk, K.M.; Hunt, W.F.; Wright, J.D. Characterization of rainwater harvesting utilization in humid regions of the United States. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2013, 49, 1398–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisano, A.; Modica, C. Rainwater harvesting as source control option to reduce roof runoff peaks to downstream drainage systems. J. Hydroinformatics 2016, 18, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, R.; Rouge, C.; Stovin, V. Quantifying the performance of dual-use rainwater harvesting systems. Water Res. X 2021, 10, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahyono, M. Optimizing rainwater harvesting systems for the dual purposes of water supply and runoff capture with study case in Bandung area, West Java. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1065, 012050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abas, P.E.; Mahlia, T. Techno-economic and sensitivity analysis of rainwater harvesting system as alternative water source. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.D.; Fletcher, T.D.; Duncan, H.P.; Bergmann, D.J.; Breman, J.; Burns, M.J. Improving the multi-objective performance of rainwater harvesting systems using real-time. Water 2018, 10, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerolin, A.; Le Nouveau, N.; de Gouvello, B. Rainwater harvesting for stormwater management: Example-based typology and current approaches for evaluation to question French practices. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Planning and Technologies for Sustainable Management of Water in the City, Lyon, France, 23–27 June 2013; p. 9P. [Google Scholar]

- Mogano, M.M.; Okedi, J. Assessing the benefits of real-time control to enhance rainwater harvesting at a building in Cape Town, South Africa. Water SA 2023, 49, 273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, K.D.; Hunt, W.F. Enhancing stormwater management benefits of rainwater harvesting via innovative technologies. J. Environ. Eng. 2016, 142, 04016039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi Aad, M.P.; Suidan, M.T.; Shuster, W.D. Modeling techniques of best management practices: Rain barrels and rain gardens using EPA SWMM-5. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2010, 15, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, R.; Melville-Shreeve, P.; Butler, D.; Stovin, V. A Critical evaluation of the water supply and stormwater management performance of retrofittable domestic rainwater harvesting systems. Water 2020, 12, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.P.; Hunt, W.F. Performance of rainwater harvesting systems in the southeastern United States. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.C.Y. Urban Hydrology and Hydraulic Design; Water Resources Publications, LLC.: Lone Tree, CO, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Water Resources Planning Branch, Water Resources Agency, Ministry of Economic Affairs (WRA, MOEA). Flow Control Technical Manual; Water Resources Planning Branch, Water Resources Agency, Ministry of Economic Affairs (WRA, MOEA): Taiwan, China, 2020.

- Swamee, P.K.; Jain, A.K. Explicit equations for pipe-flow problems. J. Hydraul. Division ASCE 1976, 102, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, T.A.; Mein, R.G. River and Reservoir Yield; Water Resources Publications: Highlands Ranch, CO, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Eagleson, P.S. Dynamic Hydrology; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, D.; Pearson, F.; Moore, E.; Sun, J.K.; Valentine, R. Feasibility of Rainwater Collection Systems in California. Contribution No. 173; Californian Water Resources Centre, University of California: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Liaw, C.H.; Tsai, Y.L. Optimum storage volume of rooftop rain water harvesting systems for domestic use. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2004, 40, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.D.; Lee, R.R. Economics of Water Resources Planning; McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Statistics, First Quarter of 2024 National Statistical Data, Ministry of Interior, Taipei, Taiwan, 2024. Available online: https://pip.moi.gov.tw/V3/E/SCRE0301.aspx (accessed on 28 June 2024). (In Chinese)

- Hydraulic Engineering Office. Works Bureau, Planning and Design Specifications for Stormwater Sewer System in Taipei City; Taipei City Government: Taipei, Taiwan, 2010. (In Chinese)

- Taiwan Climate Change Projection Information and Adaptation Knowledge Platform (TCCIP), Application of Rainfall Frequency Analysis in Assessing the Impacts of Climate Change, Newsletter Issue No. 62. Available online: https://tccip.ncdr.nat.gov.tw/index.aspx (accessed on 3 July 2024). (In Chinese)

- Water Resources Planning Branch Office, Water Resources Agency. Derivation of Rainfall-Intensity-Duration Formula in Taiwan; Ministry of Economic Affair: Taiwan, China, 2024. (In Chinese)

- Central Weather Bureau. New Rainfall Classification Definitions and Warning Precautions Description Document; Ministry of Transportation and Communications: Taiwan, China, 2020. (In Chinese)

- Central Weather Bureau. Climate Observation Data Inquire Service (CODIS); Ministry of Transportation and Communications: Taipei, Taiwan, 2024. Available online: https://codis.cwa.gov.tw/StationData (accessed on 16 January 2024). (In Chinese)

- Central Weather Bureau. Monthly Average Rainfall Statistics from 1991 to 2020; Ministry of Transportation and Communications: Taipei, Taiwan, 2024. Available online: https://www.cwa.gov.tw/V8/C/C/Statistics/monthlymean.html (accessed on 13 August 2024). (In Chinese)

| Representative Buildings | Roof Area (m2) | Tank Volume | Number of Floors | Households on Each Floor | Number of Residents | Water Demand (m3/Day) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated (m3) | Practical (m3) | ||||||

| Detached house (DH) | 125 | 5.53 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.3 |

| Four-story building (FSB) | 250 | 13.83 | 15 | 4 | 2 | 24 | 2.4 |

| Eight-story building (ESB) | 500 | 27.67 | 30 | 8 | 4 | 96 | 9.6 |

| Variables | DH | FSB | ESB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roof area (m2) | 125 | 250 | 500 |

| Tank size (m3) | 6 | 15 | 30 |

| Demand (m3/day) | 0.3 | 2.4 | 9.6 |

| Rainfall data | The 2, 5, and 10 year return periods design storm with rainfall duration of 120 min and time resolution of 5 min intervals. | ||

| Discharge outlet location | CSFD-0, CSFD-25, CSFD-50, CSFD-75, and CSFD-100 | ||

| Discharge outlet diameters (mm) | 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, and 50 | ||

| Assessment indicator | Peak flow mitigation rate and peak flow lag times | ||

| Classification | Heavy Rain (HR) | Torrential Rain (TR) | Severe Torrential Rain (STR) | Extreme Torrential Rain (ETR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-duration | Above 40 mm/h (S-HR) | Above 100 mm/3 h (S-TR) | Above 200 mm/3 h (S-STR) | - |

| Long-duration | Above 80 mm/24 h (L-HR) | Above 200 mm/24 h (L-TR) | Above 350 mm/24 h (L-STR) | Above 500 mm/24 h (ETR) |

| Variables | DH | FSB | ESB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roof area (m2) | 125 | 250 | 500 |

| Tank size (m3) | 6 | 15 | 30 |

| Demand (m3/day) | 0.3 | 2.4 | 9.6 |

| Rainfall data | S-HR, L-HR, S-TR, L-TR, S-STR, L-STR, and ETR events (1 h interval) | ||

| Discharge outlet location | CSFD-0, CSFD-25, CSFD-50, CSFD-75, and CSFD-100 | ||

| Discharge outlet diameters (mm) | The optimal diameter determined by design storms analysis | ||

| Assessment indicator | Peak flow mitigation rate | ||

| Variables | DH | FSB | ESB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roof area (m2) | 125 | 250 | 500 | |

| Tank size (m3) | 6 | 15 | 30 | |

| Demand (m3/day) | 0.3 | 2.4 | 9.6 | |

| Rainfall data | Continuous rainfall data from years 2014–2023 (1 h intervals) | |||

| Discharge outlet location | Scenario 1 | CSFD-0 throughout the year | ||

| Scenario 2 | CSFD-0, CSFD-25, CSFD-50, CSFD-75, and CSFD-100 throughout the year | |||

| Scenario 3 | CSFD-0 in dry season and CSFD-0, CSFD-25, CSFD-50, CSFD-75, and CSFD-100 in wet season | |||

| Discharge outlet diameters (mm) | The optimal diameter determined by design storms and probably hazardous rainfall events verification | |||

| Indicators | Water supply reliability, annual water supply and regulated stormwater release with incremental analysis | |||

| Representative Building | Feasible Discharge Outlet Diameter | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Year Return Period | 5-Year Return Period | 10-Year Return Period | |

| DH | 10 mm | 15 mm | 15 mm |

| FSB | - | 15 mm | 20 mm |

| ESB | - | 15 mm | 25 mm |

| Design Storm | Representative Buildings | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DH | FSB | ESB | |||||||

| conv. RWHS | PR-RWHS (1) | Difference (2) | conv. RWHS | PR-RWHS | Difference | conv. RWHS | PR-RWHS | Difference | |

| 2-year | 83.4% | 78.4~87.9% | −5.0~+4.5% | 100% | 89.4~95.0% | −5.0~−10.6% | 100% | 93.5~97.6% | −2.4~−6.5% |

| 5-year | 53.9% | 60.8~75.6% | +6.9~+21.7% | 70.5% | 70.5~86.6% | 0.0~+16.1% | 77.8% | 78.3~92.4% | +0.5~+14.6% |

| 10-year | 38.8% | 38.8~73.5% | 0.0~+34.7% | 49.1% | 49.1~62.4% | 0.0~+13.3% | 49.1% | 49.1~70.0% | 0.0~+20.9% |

| No. | Rainfall Timing | Duration (h) | AR (mm) | No. | Rainfall Timing | Duration (h) | AR (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-HR events | |||||||

| 1 | 18 August 2015, 3–6 p.m. | 4 | 91.5 | 6 | 13 August 2021, 12–2 p.m. | 3 | 71.5 |

| 2 | 15 May 2016, 3–7 a.m. | 5 | 67.4 | 7 | 4 August 2022, 1–3 p.m. | 3 | 46.5 |

| 3 | 20 May 2019, 6–11 a.m. | 6 | 77.4 | 8 | 22–23 May 2023, 5 p.m. (22 May)–12 a.m. (23 May) | 8 | 82.5 |

| 4 | 26 July 2019, 1–3 p.m. | 3 | 77.0 | 9 | 30 June 2023, 1–4 p.m. | 4 | 89.0 |

| 5 | 21 August 2019, 1–2 p.m. | 2 | 70.5 | 10 | 20 August 2023, 12–4 p.m. | 5 | 69.5 |

| L-HR events | |||||||

| 1 | 8–10 February 2014, 9 p.m. (8 February)–1 a.m. (10 February) | 29 | 96.0 | 15 | 28 September 2019, 1 a.m.–6 p.m. | 18 | 94.5 |

| 2 | 28–29 May 2014, 8 p.m. (28 May)–6 p.m. (29 May) | 23 | 80.5 | 16 | 22–24 May 2020, 3 p.m. (22 May)–12 p.m. (24 May) | 46 | 145.4 |

| 3 | 5–6 June 2014, 9 p.m. (5 June)–4 p.m. (6 June) | 21 | 107.0 | 17 | 29 May 2020, 12 a.m.–3 p.m. | 16 | 120 |

| 4 | 21–22 September 2014, 4 p.m. (21 September)–9 a.m. (22 September) | 18 | 165.0 | 18 | 4 August 2020, 5 a.m.–7 p.m. | 13 | 90.0 |

| 5 | 18–19 June 2016, 2 p.m. (18 June)–12 a.m. (19 June) | 11 | 103.8 | 19 | 28 August 2020, 11 a.m.–10 p.m. | 12 | 95.5 |

| 6 | 18–19 September 2016, 5 a.m. (18 September)–7 a.m. (19 September) | 27 | 85.2 | 20 | 23–24 July 2021, 10 a.m. (23 July)–12 p.m. (24 July) | 27 | 138.0 |

| 7 | 28 September 2016, 2 a.m.–11 p.m. | 22 | 181.8 | 21 | 6–7 August 2021, 8 a.m. (6 August)–7 p.m. (7 August) | 36 | 147.0 |

| 8 | 3 June 2017, 7 a.m.–7 p.m. | 13 | 159.5 | 22 | 12 September 2021, 8 a.m.–7 p.m. | 12 | 86.5 |

| 9 | 12 October 2017, 5 a.m.–9 p.m. | 17 | 115.2 | 23 | 11–12 October 2021, 12 a.m. (11 October)–10 p.m. (12 October) | 35 | 119.5 |

| 10 | 13–15 October 2017, 7 a.m. (13 October)–12 a.m. (15 October) | 42 | 163.5 | 24 | 28–29 Mar 2202, 1 a.m. (28 Mar)–3 a.m. (29 Mar) | 27 | 86.5 |

| 11 | 8–9 January 2018, 1 a.m. (8 January)–5 a.m. (9 January) | 29 | 94.5 | 25 | 25–26 May 2022, 5 a.m. (25 May)–1 a.m. (26 May) | 21 | 130.5 |

| 12 | 10–11 July 2018, 3 p.m. (11 July)–9 a.m. (11 July) | 19 | 106.0 | 26 | 26–27 May 2022, 12 p.m. (26 May)–12 p.m. (27 May) | 25 | 90.0 |

| 13 | 11 June 2019, 1 a.m.–7 p.m. | 19 | 111.5 | 27 | 4 June 2023, 1–7 p.m. | 7 | 137.0 |

| 14 | 2–3 July 2019, 1 p.m. (2 July)–4 a.m. (3 July) | 16 | 138.5 | ||||

| S-TR events | |||||||

| 1 | 7 January 2017, 3–11 a.m. | 9 | 149.0 | 4 | 22 July 2019, 2–4 p.m. | 3 | 118.5 |

| 2 | 2 August 2017, 12–2 p.m. | 3 | 100.5 | 5 | 23 June 2023, 1–4 p.m. | 4 | 123.0 |

| 3 | 8 September 2018, 3–9 p.m. | 7 | 144.5 | 6 | 10 August 2023, 2–5 p.m. | 4 | 114.5 |

| L-TR events | |||||||

| 1 | 7–9 August 2015, 8 p.m. (7 August)–12 a.m. (9 August) | 17 | 318.9 | 3 | 15–17 October 2022, 8 p.m. (15 October)–4 a.m. (17 October) | 33 | 269.0 |

| 2 | 27–29 September 2015, 4 p.m. (27 September)–2 a.m. (29 September) | 35 | 224.9 | ||||

| L-STR events | |||||||

| 1 | 20–21 May 2014, 9 a.m. (20 May)–8 p.m. (21 May) | 36 | 411.5 | ||||

| Rainfall Event Levels | Representative Buildings | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DH | FSB | ESB | |||||||

| conv. RWHS | PR-RWHS (1) | Difference (2) | conv. RWHS | PR-RWHS | Difference | conv. RWHS | PR-RWHS | Difference | |

| S-HR | 16.6% | 32.6~44.6% | +16~+28.0% | 51.1% | 65.5~73.3% | +14.4~+22.2% | 92.4% | 78.4~85.2% | −7.2~−14.0% |

| S-TR | 20.8% | 28.9~54.7% | +8.1~+33.9% | 47.0% | 52.9~65.4% | +5.9~+18.4% | 48.6% | 49.7~58.4% | +1.1~+9.5% |

| L-HR | 9.8% | 8.6~20.6% | −1.2~+10.8% | 30.4% | 45.5~48.3% | +15.1~+17.9% | 45.1% | 58.0~61.5% | +12.9~+16.4% |

| L-TR | 0.0% | 6.7~20.5% | +6.7~+20.5% | 0.0% | 0.0~32.1% | 0.0~+32.1% | 7.0% | 7.0~9.7% | 0.0~+2.7% |

| Locations | Average Annual Water Supply Reliability | ||||

| Scenario 1 (A) | Scenario 2 (B) | Difference (A − B) | Scenario 3 (C) | Difference (A − C) | ||

| CSFD-0 | 74.8% | 74.8% | - | 74.8% | - | |

| CSFD-25 | 74.8% | 71.6% | −3.2% | 74.4% | 0.4% | |

| CSFD-50 | 74.8% | 67.7% | 7.1% | 73.3% | 1.5% | |

| CSFD-75 | 74.8% | 53.4% | 21.4% | 66.1% | 8.7% | |

| CSFD-100 | 74.8% | 2.0% | 72.8% | 41.8% | 33.0% | |

| Locations | Average Annual Water Supply Reliability | ||||

| Scenario 1 (A) | Scenario 2 (B) | Difference (A − B) | Scenario 3 (C) | Difference (A − C) | ||

| CSFD-0 | 45.5% | 45.5% | - | 45.5% | - | |

| CSFD-25 | 45.5% | 41.8% | 3.7% | 43.3% | 2.2% | |

| CSFD-50 | 45.5% | 36.2% | 9.3% | 39.9% | 5.6% | |

| CSFD-75 | 45.5% | 28.9% | 16.6% | 35.0% | 10.5% | |

| CSFD-100 | 45.5% | 0.03% | 45.47% | 22.3% | 23.2% | |

| Locations | Average Annual Water Supply Reliability | ||||

| Scenario 1 (A) | Scenario 2 (B) | Difference (A − B) | Scenario 3 (C) | Difference (A − C) | ||

| CSFD-0 | 25.4% | 25.4% | - | 25.4% | - | |

| CSFD-25 | 25.4% | 24.0% | 1.4% | 24.3% | 1.1% | |

| CSFD-50 | 25.4% | 21.6% | 3.8% | 22.5% | 2.9% | |

| CSFD-75 | 25.4% | 18.1% | 7.3% | 20.1% | 5.3% | |

| CSFD-100 | 25.4% | 4.0% | 21.4% | 13.4% | 12.0% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsai, H.-Y.; Fan, C.-M.; Liaw, C.-H. Identifying the Layout of Retrofitted Rainwater Harvesting Systems with Passive Release for the Dual Purposes of Water Supply and Stormwater Management in Northern Taiwan. Water 2024, 16, 2894. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16202894

Tsai H-Y, Fan C-M, Liaw C-H. Identifying the Layout of Retrofitted Rainwater Harvesting Systems with Passive Release for the Dual Purposes of Water Supply and Stormwater Management in Northern Taiwan. Water. 2024; 16(20):2894. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16202894

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsai, Hsin-Yuan, Chia-Ming Fan, and Chao-Hsien Liaw. 2024. "Identifying the Layout of Retrofitted Rainwater Harvesting Systems with Passive Release for the Dual Purposes of Water Supply and Stormwater Management in Northern Taiwan" Water 16, no. 20: 2894. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16202894

APA StyleTsai, H.-Y., Fan, C.-M., & Liaw, C.-H. (2024). Identifying the Layout of Retrofitted Rainwater Harvesting Systems with Passive Release for the Dual Purposes of Water Supply and Stormwater Management in Northern Taiwan. Water, 16(20), 2894. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16202894