Abstract

Lack of access to piped water, as well as inadequate quantity and quality of water, are risk factors for acute gastrointestinal infections. In 2022, 4.9% of households in Mexico did not have piped water; 19.3% lacked, at some point, sufficient water for hygiene; and 18.9% perceived that the water was unfit for human consumption. During the same year, at least 1,441,226 people suffered from a gastrointestinal infection. Households without access to piped water and with insufficient water for hygiene were 27% more likely to suffer from a gastrointestinal infection than households with piped water and a sufficient supply for hygiene (odds ratio: 1.27; CI 95%: 1.26–1.28). The latent class analysis shows that 22% of households belong to the high-risk class of suffering gastrointestinal infections associated with a lack of piped water, insufficient quantity, and poor quality of water. These results provide elements for the design of public health programs through the supply of water for consumption and sanitation services.

1. Introduction

Some studies indicate that up to 35% of gastrointestinal disease cases may be related to the drinking water supply [1,2,3]. Other studies have identified the major waterborne pathogens that cause diarrhea and other illnesses [4,5]. While water filtration and chlorination can eliminate many of these pathogens, the lack of piped drinking water infrastructure within households, as well as intermittent distribution and lack of or inadequate water purification, puts the health of millions of households in Mexico at risk.

Lack of sufficient water for personal hygiene is a risk factor for acute gastrointestinal infections (AGIs) and other diseases such as conjunctivitis, scabies, leprosy, ascariasis, trichiniasis, hookworm, amebiasis, dysentery, and paratyphoid fever, among others [5,6]. In this sense, the absence, quantity, and quality of water for human consumption are factors that determine the risk of AGI. According to the National Public Health Survey 2022 (ENSANUT 2022) [7], 1,822,260 households do not have piped water in their homes (4.9% of the total); in 7,220,829 households, at least one member could not wash his or her hands after performing an unhygienic activity because there was not enough water (19.23%); and 7,112,090 households did not have drinking water suitable for human consumption (18.94%). Households in urban areas with a lack of water supply are 37% more likely to suffer AGIs than households not lacking a water supply.

According to the ENSANUT (2022) [7], at least during the three months prior to the survey, 1,441,296 people had some AGI; 53.2% were women, 18.37% were under 5 years old, and 9.5% were over 65 years old. The objective of this work is to estimate the risk profiles of AGI in Mexican households. For this purpose, the latent class analysis (LCA) method was used, which allowed the identification of classes or subgroups that were labeled as AGI risk profiles. The observable variables used in the LCA were incidence of AGI and lack of piped water within the dwelling, sufficient water for personal hygiene, and water suitable for human consumption. Other covariates used to assess and differentiate risk profiles were household income and rural or urban environment. Information on these variables at the household and household member level was obtained from the ENSANUT 2022 [7].

There is an extensive literature on risk factors and prevention of waterborne AGI, lack of water, and hygiene habits, which can be classified according to the variables used. Among the studies that estimate the risk of AGI due to lack of water, those that analyze the association between the absence of piped water and an increased risk of AGI caused by protozoa such as Giardia stand out. Chute et al. (1987) [8] found that households that consumed water from shallow wells or surface water sources were 2.1 times more likely to suffer from giardiasis than those that consumed water from the municipal water system in New England, United States of America. Bello et al. (2011) [9] found that the Cuban population under 5 years of age without piped water in their homes was 3.27 times more likely to suffer from Giardia infection than the population of the same age and with access to piped water. Choy et al. (2014) [10] found that the population that consumed water from wells or rivers had 2.1 times the risk of suffering from giardiasis.

The studies described below found a positive association between AGIs caused by bacteria and lack of piped water. Several studies have found that households that rely on well water are more likely to suffer from AGIs caused by Vibrio cholerae. For instance, Izadi et al. (2006) [11] found that the population that consumed well water in a southern province of Iran was 2.83 times more likely to have AGIs caused by Vibrio cholerae. In the work of Nanzaluka et al. (2020) [12], it was found that the population of Lusaka, Zambia, that consumed well water was 2.4 times more likely to have AGIs caused by Vibrio cholerae. In a study carried out in the region of British Columbia, Canada, Galanis et al. (2014) [13] found that households that consumed water from wells had a 40% higher probability of suffering from AGIs caused by Campylobacter compared with households with a supply from the municipal water system. In another study, Zamir et al. (2022) [14] reported that the population that consumed water from springs in the Golan Heights, Israel, was 15.5 times more likely to contract AGIs caused by Leptospira serovar bacteria. These studies measure the association between exposure to risk factors and cases of AGI using the ratio of probabilities of AGI cases in groups with exposure to risk factors and without exposure, called the odds ratio. A higher odds ratio indicates a greater probability that an event or case will be exposed.

Table 1 shows the odds ratios of contracting an AGI associated with a lack of piped water in dwellings by type of pathogen.

Table 1.

Risk factors due to lack of piped water in the home.

Of the studies that analyze the association between AGI and water quality, two groups can be distinguished, those that identify the consumption of unchlorinated, unboiled water as a risk factor and those that find that consuming water from the municipal system constituted a risk factor. Within the first group is the one conducted by Nguyen et al. (2014) [15], who highlight that, during an outbreak of Vibrio cholerae in Sierra Leone, Africa, the population that consumed unboiled non-potable water was 3.4 times more likely to contract an AGI caused by this pathogen. De Guzman et al. (2015) [16] found that the population that consumed unchlorinated, unboiled water in the town of Nabua, Philippines, was 3.6 times more likely to contract an AGI from Vibrio cholerae. He et al. (2009) [17] found that the student population in Sichuan, China, who consumed water from an untreated water well were 3.7 times more likely to suffer from AGIs caused by Shigella flexneri. Another study that found a positive association between AGIs and consumption of unchlorinated, unboiled water was developed by El Qouqa et al. (2011) [18]; among its results, it highlights that the population under 12 years of age in the Gaza Strip who consumed unchlorinated, unboiled water was 2.93 times more likely to contract AGIs caused by Yersinia.

The group of studies on the risk of AGI associated with the consumption of water from municipal water systems can be divided by the type of pathogen identified. Seven studies found a positive association between consumption of water from municipal systems and AGIs caused by Norovirus and Rotavirus [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. On the other hand, six studies found a positive association between consumption of unfiltered water from municipal systems and AGIs caused by protozoa such as Cryptosporidium and Giardia [9,10,26,27,28,29]. Among the studies that found a positive association between AGIs caused by bacteria and consumption of water from municipal systems were those that identified Shigella flexneri [30,31], Campylobacter [32,33,34], Salmonella [35], and Escherichia coli [36]. Table 2 shows the risk factors by type of pathogen.

Table 2.

Risk factors due to lack of potable, safe water for human consumption.

Regarding studies that estimate the association between AGIs and hygiene, these are divided between those that measure the association between the practice of hygiene habits such as hand washing before and after using the toilet as a protective factor for AGI and those that analyze the association between the absence of hygiene habits such as hand washing before eating and after using the toilet as risk factors for AGI. Within the first group are eight studies, seven of which find a negative association between hand washing with soap and AGI caused during outbreaks of Vibrio cholerae [12,39,40,41,42,43,44] and one due to Shigella [45], as shown in Table 3. In the second group, there are four studies that found a positive association between not washing hands before eating and/or after using the toilet and AGI, three of which identified Vibrio cholerae bacteria as the cause [11,46,47] and one positively associated with AGIs caused by Giardia [10]. On the other hand, the results obtained by Chompook et al. (2006) [48] indicate that having sufficient water for personal care and hygiene is a protective measure against AGIs caused by Shigella. The study by Choy et al. (2014) [10] indicates that not washing hands after playing with animals is positively associated with AGIs caused by protozoa such as Giardia.

Table 3.

Risk factors due to lack of hygiene.

2. Materials and Methods

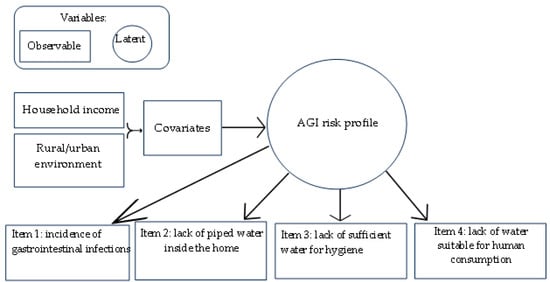

The data used to estimate the association between AGI and lack of piped water sufficient for hygiene and fit for human consumption in Mexican households for the year 2022 were obtained from ENSANUT (2022) [7]. The conceptual theoretical framework used to estimate the AGI risk profile for lack of piped, hygienic, and safe water for human consumption is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the latent class model.

The latent variable represents risk profile categories underlying AGIs associated with lack of access to piped water, as well as inadequate quantity and quality of water, in Mexican households. The model contains four items, one for incidence of gastrointestinal infections and three for water scarcity, referring to lack of piped water inside the dwelling, insufficient water for personal and pet hygiene, as well as perception of water unfit for human consumption.

2.1. Description of the Latent Class Analysis Method

Latent class analysis is a multivariate statistical technique that makes it possible to identify the presence of one or more latent variables across a set of observed variables [49]. This method was first introduced by Lazarsfeld (1968) [50] as a tool for the construction of dichotomous variables [51]. The data analyzed are discrete-valued variables, so they are considered indicators of underlying or latent information, which makes it an appropriate method for the analysis of sociological data obtained through interviews [52]. The clusters or classes that emerge are associated with the categories of a latent variable Ƴ, which is underlying a set of categorical and directly measurable variables X1, X2, … Xp. This simplifies the creation of clusters whose characteristics are not easy to measure directly. Thus, clusters are constituted in a non-hierarchical manner, based on specific (indicators of measurable variables) and subjective (linked to latent classes) criteria [53].

The model used in this analysis establishes relationships between the probabilities of belonging to each category of the latent variable. Some of these variables play the role of model parameters, which are estimated using the maximum likelihood method. Subsequently, a series of extensions of the initial model were made with the inclusion of more than one latent variable, the consideration of continuous latent variables, and the use of regression models with latent variables, among others [53].

where the number of levels in each variable is . Thus, the model expresses that the probability distribution of the measurable responses is a weighted sum of the probabilities . In the relation is the proportion of elements in the latent class k. If we add that within each latent class the manifest variables are mutually independent, the model can be expressed as follows:

Subject to the following constraint:

This method allows the exhaustive grouping of the population elements into K clusters. From the pattern of Bayes’ theorem and the pattern of responses , it is possible to assign the population elements to each of the k latent classes, as described in the following expression:

Thus, all elements whose probability is the highest are signed in class k of the latent variable. When each manifest variable Xi is dichotomous with values of 0 and 1, the classification rule is written as follows:

where . The parameters and are not known and must be estimated from the data. For parameter estimation, the model uses an EM (maximum expectation) algorithm that maximizes the maximum likelihood L function. As can be seen, latent class analysis is a parametric model that uses observed data to estimate the model parameters [54]. Model adequacy refers to the number of latent categories that will allow a better fit to the model. At the sample level, it is performed to compare the frequencies in the latent variables predicted by the model with the frequencies observed from the data; if the difference between the two is considerable, this means that the model does not fit the data. The measures for this objective are the chi-square statistic X2 and the likelihood ratio .

where is the observed frequency and is the expected one.

The purpose of fitting the model is to select those that fit the data adequately, avoiding the inclusion of an excess of parameters (latent classes). Although a model with many classes may fit the data well, the frequency of the data may be insufficient to meet the chi-square distribution. Therefore, fit measures that evaluate and penalize the use of an excessive number of latent classes are usually employed. In that sense, the measures usually used are the Akaike’s criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), which are expressed as follows:

It is distinguished by the following characteristics: in a random sample, each individual can belong exclusively to a latent class. The response probability for a specific item is constant among individuals of the same latent class but varies among those belonging to different classes. Moreover, if an individual belongs to a latent class, his or her responses to each item are conditionally independent [51]. One of the advantages of implementing this multivariate method to the analysis of the risk of AGI associated with a lack of piped water or water sufficient for hygiene and fit for human consumption, is that it allows the identification and classification of the population by risk profiles based on the observable variables and covariates described in Figure 1, i.e., the percentage of the estimated population in households by level or category of risk to AGI caused by various pathogens (bacteria, viruses, and/or protozoa).

2.2. Description of Data

Table 4 shows the description of the variables and covariates used to obtain the odds ratio using univariate statistics as well as the risk profile for AGIs associated with a water deficiency described in Figure 1, using the multivariate ACL statistical method.

Table 4.

Description of variables and observable covariates.

2.3. Description of Variables and Observable Covariates

Table 5 contains the descriptive statistics of the observable variables and covariates in dichotomous and categorical form.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics of observable variables and covariates.

3. Results

To validate the conceptual theoretical framework used, the odds ratio was used as a criterion, that is, the quotient of the probability that a member of the household suffers from an AGI given that he or she has some water deficiency and the probability that he or she suffers from an AGI given that he or she does not have water deficiencies. Table 6 shows the odds ratios obtained for the estimated population with AGIs with and without water deprivation.

Table 6.

Contingency table, probability, and odds ratio for AGI.

According to the odds ratio obtained, households with some water deprivations are 27% more likely to suffer from AGI than households without water deprivation, with a 95% confidence interval [26.7–27.6%]. Because both interval limits are greater than unity, a positive association between water deprivation and the incidence of AGI, and therefore as a risk factor, is corroborated. This result validates the conceptual theoretical framework of the latent class analysis described in Figure 1. Once the relevance of the approach used to identify subgroups or classes of households by AGI risk profile was validated, the optimal number of classes was estimated according to the fit statistic and the Akaike and Bayes information criteria. Table 7 shows the adjustment statistics and information criteria.

Table 7.

Fitting statistics and information criteria.

For the model with two latent classes, the null hypothesis that the estimated model fits as well as the saturated model is rejected, failing in favor of a model with three classes; however, when estimating the model with three classes, it was not possible to obtain the convergence values of the maximum likelihood function, which prevented the estimation, which is why it was decided to select the model with two latent classes. Subsequently, the classes or subgroups were labeled into two AGI risk profiles as low-risk class and high-risk class, according to the predicted probabilities. Table 8 contains the predicted conditional probability for each observable variable by risk profile.

Table 8.

Predicted probability by latent classes.

The probability of giving an affirmative answer to each of the questions posed in each item indicates belonging to class 1, known as low-risk, or class 2, known as high-risk. Thus, households classified in the low-risk class showed a 3% probability of suffering from AGI, lower than the 4.6% obtained in households labeled as the high-risk class. Households with a 97.2% probability of having piped water inside the dwelling were classified as low-risk, while households with a 92.6% probability of having piped water were in the high-risk class. Households with a 6% probability of not having been able to wash their hands due to a lack of water were classified as low-risk, while households with a 70% probability were classified as high-risk. Households with a 2.3% probability of ever having had water unfit for human consumption were placed in the low-risk class, while households with a probability of 81.5% were placed in the high-risk class. The probability of a household belonging to each risk profile class for AGI was also estimated. Table 9 contains the probabilities of membership by risk class.

Table 9.

Probability of belonging to each class and estimated households by class.

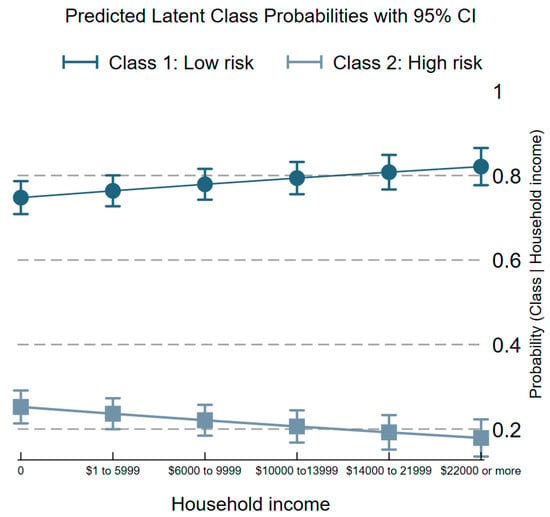

The results obtained indicate that the probability of households belonging to the low-risk-profile class 1 is 78%, with an estimated value of 29,893,016 households when using expansion factors. Figure 2 shows the probability of households belonging to a low- or high-risk class.

Figure 2.

Probability of belonging to a risk profile, given income level.

Figure 2 reveals that the probability of households belonging to the low-risk profile increases as household income increases; consequently, the probability of belonging to the high-risk profile decreases as household income increases. Figure 3 shows the probability of households belonging to a low- or high-risk profile given the rural or urban environment.

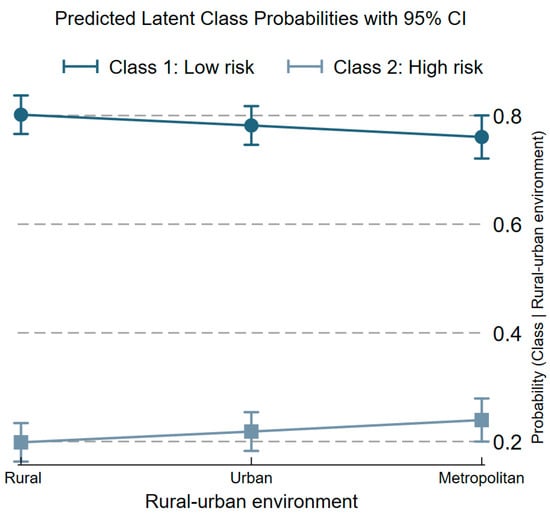

Figure 3.

Probability of households to belong to some risk profile, given the environment.

As shown in Figure 3, the probability of belonging to the high-risk class or profile increases with the size of the localities, reaching the highest value in metropolitan areas. This finding reveals the challenge of public agencies operating municipal drinking water and sewerage systems to reduce the lack of piped drinking water service in private homes as well as to guarantee the supply with sufficient quality, frequency, pressure, and quantity for household consumption and hygiene in Mexico.

4. Discussion

The ACL results reveal consistency between the incidence of AGI and the risk profile of the households because those households that reported that a member suffered from AGI during the last three months have a higher probability (4.6%) of belonging to the high-risk class or profile compared with the probability of belonging to the low-risk class or profile (3%), as shown in Table 8. The results of the ACL model regarding access to piped water in the home revealed that households with no lack of piped water have a higher probability (97.2%) of belonging to the low-risk class or profile to AGI compared with the probability of belonging to the high-risk class (92.6%). The above indicates that households without piped water in Mexico access alternative water sources without adequate treatment to remove bacteria or other pathogens. These results are consistent with findings reported by Chute et al., 1987 [8]; Bello et al., 2011 [9]; Choy et al., 2014 [10]; Izadi et al., 2006 [11]; Nanzaluka et al., 2020 [12]; Galanis et al., 2014 [13]; and Zamir et al., 2022 [14], who found positive associations between lack of piped water and AGIs caused by bacteria and protozoa.

Regarding the lack of water fit for human consumption (no drinking water), it was found that households that perceived that they had consumed water unfit for human consumption had a greater probability (81.5%) of belonging to the high-risk class or profile for AGI compared with the probability (2.3%) of belonging to the low-risk class or profile (3%), a result consistent with the findings of studies that found a positive association between consumption of unchlorinated water and AGIs caused by bacteria such as Vibrio cholerae, Shigella, and Yersinia [15,16,17,18]. Finally, households that reported that a member was unable to wash his or her hands after unhygienic activities due to lack of water had a higher probability (69.6%) of belonging to the high-risk class or profile compared with the probability (5.9%) of belonging to the low-risk class or profile for AGIs. These results also agree with those reported by Choy et al. (2014) [10]; Izadi et al., 2006 [11]; Mugoya et al., 2008 [44]; and Cummings et al., 2012 [45], who found positive associations between not washing hands before eating or after toileting and/or playing with animals and AGIs caused by Vibrio cholerae and Giardia.

5. Conclusions

The knowledge obtained from the extensive literature on the lack of piped, safe, and sufficient water for human consumption as factors positively associated with AGI reveals the importance of water quality control to avoid waterborne disease outbreaks as well as the importance of access to piped water and personal hygiene habits. The odds ratio obtained in this work reveals that households with at least one lack of piped water, insufficient water for hygiene, and perceived unfit water for human consumption are 27% more likely to suffer from AGIs than households with no lack. The adjustment statistic and the Akaike and Bayes information criteria of the ACL model allowed us to estimate that 7,561,769 (22%) households in Mexico are at high risk of suffering from AGIs caused by bacteria, viruses, or protozoa associated with water shortages. These results provide elements for the design of public health policy programs. In future work, we hope to carry out a spatial analysis of the risk profiles of AGIs in households with information on geographic coordinates at the municipal level.

Author Contributions

Conception and design of study: G.A.-P. and L.F.B.-M.; Acquisition of data, data curation, and software: G.A.-P. and A.M.-T.; Analysis and/or interpretation of data: G.A.-P., L.F.B.-M., A.M.-T. and E.T.-D.; Drafting the manuscript: G.A.-P., L.F.B.-M., A.M.-T. and E.T.-D.; Review and editing: L.F.B.-M. and E.T.-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste S.C., and the APC was funded by financial resources, 2024.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Consejo Nacional de Humanidades Ciencias y Tecnologías (CONAHCYT) and the Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste (CIBNOR).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Payment, P.; Richardson, L.; Siemiatycki, J.; Dewar, R.; Edwardes, M.; Franco, E. A randomized trial to evaluate the risk of gastrointestinal disease due to consumption of drinking water meeting current microbiological standards. Am. J. Public Health 1991, 81, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellard, M.E.; Sinclair, M.I.; Forbes, A.B.; Fairley, C.K. A randomized, blinded, controlled trial investigating the gastrointestinal health effects of drinking water quality. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001, 109, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Säve-Söderbergh, M.; Bylund, J.; Malm, A.; Simonsson, M.; Toljander, J. Gastrointestinal illness linked to incidents in drinking water distribution networks in Sweden. Water Res. 2017, 122, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, P.R.; Waite, M.; Ronchi, E. Drinking Water and Infections Disease: Establishing the Links; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2002; pp. 1–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbolt, N.J. Microbial contamination of drinking water and disease outcomes in developing regions. Toxicology 2004, 198, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, G.F.; Bradley, D.J.; White, A.U. Drawers of Water Domestic Water Use in East Africa; University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- ENSANUT CONTINUA 2022. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición CONTINUA 2022. Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública. 2022. Available online: https://ensanut.insp.mx/encuestas/ensanutcontinua2022/descargas.php (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Chute, C.G.; Smith, R.P.; Baron, J.A. Risk Factors for Endemic Giardiasis. Am. J. Public Health 1987, 77, 585–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello, J.; Núñez, F.A.; González, O.M.; Fernández, R.; Almirall, P.; Escobedo, A.A. Risk factors for Giardia infection among hospitalized children in Cuba. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2011, 105, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, S.H.; Al-Mekhlafi, H.M.; Mahdy, M.A.K.; Nasr, N.N.; Sulaiman, M.; Lim, Y.A.L.; Surin, J. Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Giardia Infection among Indigenous Communities in Rural Malaysia. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, S.; Shakeri, H.; Roham, P.; Sheikhzadeh, K. Vibrio cholerae outbreak in southeast of Iran: Routes of transmission in the situation of good primary health care services and poor individual hygienic practices. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 59, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanzaluka, F.H.; Davis, W.W.; Mutale, L.; Kapaya, F.; Sakubita, P.; Langa, N.; Gama, A.; N’cho, H.S.; Malambo, W.; Murphy, J.; et al. Risk Factors for Epidemic Vibrio cholerae in Lusaka, Zambia—2017. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, E.; Mak, S.; Otterstatter, M.; Taylor, M.; Zubel, M.; Takaro, T.K.; Kuo, M.; Michel, P. The association between campylobacteriosis, agriculture and drinking water: A case-case study in a region of British Columbia, Canada, 2005–2009. Epidemiol. Infect. 2014, 142, 2075–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamir, L.; Baum, M.; Bardenstein, S.; Blum, S.E.; Moran-Gilad, J.; Perry Markovich, M.; King, R.; Elnekave, E. The association between natural drinking water sources and the emergence of zoonotic leptospirosis among grazing beef cattle herds during a human outbreak. One Health 2022, 14, 100372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.D.; Sreenivasan, N.; Lam, E.; Ayers, T.; Kargbo, D.; Dafae, F.; Jambai, A.; Alemu, W.; Kamara, A.; Islam, M.S.; et al. Vibrio cholerae Epidemic Associated with Consumption of Unsafe Drinking Water and Street-Vended Water—Eastern Freetown, Sierra Leone. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012, 90, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guzman, A.; de los Reyes, V.C.; Sucaldito, M.N.; Tayagb, E. Availability of safe drinking-water: The answer to Vibrio cholerae outbreak? Nabua, Camarines Sur, Philippines, 2012. WPSAR 2015, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Han, K.; Liu, L.; Sun, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, B.; Ma, H. Shigellosis Outbreak Associated with Contaminated Well Water in a Rural Elementary School: Sichuan Province, China, June 7–16, 2009. PLoS ONE 2012, 10, e47239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Qouqa, I.A.; Jarou, M.A.E.; Samaha, A.S.A.; Afifi, A.S.A.; Al Jarousha, A.M.K. Yersinia enterocolitica infection among children aged less than 12 years: A case–control study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 15, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werber, D.; Laušević, D.; Mugoša, B.; Vratnica, Z.; Ivanović-Nikolić, L.; Žižić, L.; Alexandre-Bird, A.; Fiore, F.; Ruggeri, F.M.; Di Bartolo, I.; et al. Massive outbreak of viral gastroenteritis associated with consumption of municipal drinking water in a European capital city. Epidemiol. Infect. 2009, 137, 1713–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitenmoser, A.; Fretz, R.; Schmid, J.; Besl, A.; Etter, R. Outbreak of acutegstrointeritis due to a washwater-contaminated water supply, Switzerland, 2008. J. Water Health 2011, 9, 259–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, C.; Andersson, Y.; Allestam, G.; Lindqvist, A.; Nenonen, N.; Bergstedt, O. Epidemiology and estimated costs of a large waterborne outbreak of norovirus infection in Sweden. Epidemiol. Infect. 2014, 142, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellou, K.; Katsioulis, A.; Potamiti-Komi, M.; Pournaras, S.; Kyritsi, M.; Katsiaflaka, A.; Kallimani, A.; Hadjichristodoulou, C. A large waterborne gastroenteritis outbreak in central Greece, March 2012: Challenges for the investigation and management. Epidemiol. Infect. 2014, 142, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryfinopoulou, K.; Kyritsi, M.; Mellou, K.; Kolokythopoulou, F.; Mouchtouri, V.A.; Potamiti-Komi, M.; Lamprou, A.; Hadjichristodoulou, C. Norovirus waterborne outbreak in Chalkidiki, Greece, 2015: Detection of GI.P2_GI.2 and GII.P16_GII.13 unusual strains. Epidemiol. Infect. 2019, 147, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacqueline, C.; del Valle Arrojo, M.; Moreira, P.B.; Feijóo, M.A.R.; Cabrerizo, M.; Fernandez-Garcia, M.D. Norovirus GII.3[P12] Outbreak Associated with the Drinking Water Supply in a Rural Area in Galicia, Spain, 2021. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orysbayeva, M.; Zhuman, B.; Turegeldiyeva, D.; Horth, R.; Zhakipbayeva, B.; Singer, D.; Smagul, M.; Nabirova, D. Outbreak of acute gastroenteritis associated with drinking water in rural Kazakhstan: A matched case-control study. PLoS Glob Public Health 2022, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, S.; Reacher, M.; Casemore, D.P.; Verlander, N.Q.; Chalmers, R.; Knowles, M.; Williams, J.; Osborn, K.; Richards, S. Sporadic Cryptosporidiosis, North Cumbria, England, 1996–2000. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1007–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, B.W.; Chalmers, R.M.; Carnicer-Pont, D.; Casemore, D.P. A Cryptosporidium hominis outbreak in North-West Wales associated with low oocyst counts in treated drinking water. J. Water Health 2010, 8, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, K.G.J.; Young, D.; Robertson, C.; Ahmed, S.; Ramsay, C.N. Reduction in cryptosporidiosis associated with introduction of enhanced filtration of drinking water at Loch Katrine, Scotland. Epidemiol. Infect. 2014, 142, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quihui-Cota, L.; Morales-Figueroa, G.G.; Javalera-Duarte, A.; Ponce-Martínez, J.A.; Valbuena-Gregorio, E.; López-Mata, M.A. Prevalence and associated risk factors for Giardia and Cryptosporidium infections among children of northwest Mexico: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaddiwudhipong, W.; Karintraratana, S.; Kavinum, S. A common-source outbreak of shigellosis involving a piped public water supply in northern Thai communities. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1995, 98, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saha, T.; Murhekar, M.V.; Hutin, Y.J.; Ramamurthy, T. An urban, water-borne outbreake of diarrhoea and shigellosis in a district town in easter India. Natl. Med. J. India 2009, 22, 237–239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuusi, M.; Klemets, P.; Miettinen, I.; Laaksonen, I.; Sarkkinen, H.; Hänninen, M.L.; Rautelin, H.; Nuorti, J.P. An outbreak of gastroenteritis from a non-chlorinated community water supply. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2004, 58, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.E.; Bowen, A.B.; Perez, N.E.; Sarisky, J.P.; Shepherd, C.A.; Miller, M.D.; Hubbard, B.C.; Browne, L.H. Waterborne Outbreak of Gastroenteritis with Multiple Etiologies among Resort Island Visitors and Residents: Ohio, 2004. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 44, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, J.C.; Barakat, M.; Drole, M.-J.; Gauvin, D.; Huot, C. Waterborne outbreaks: A public health concern for rural municipalities with unchlorinated drinking water distribution systems. Can. J. Public Health 2020, 111, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.; Sloan, D.; Cooper, T.; Morton, B.; Hunter, I. A waterborne outbreak of Salmonella Saintpaul. Commun. Dis. Intell. 2000, 24, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rakesh, P.S.; Narayanan, V.; Pillai, S.S.; Retheesh, R.; Dev, S. Investigation of an Outbreak of Acute Gastroenteritis in Kollam, Kerala, India. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2016, 7, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mridha, P.; Biswas, A.K.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Murhekar, M.V. The 2010 Outbreak of Vibrio cholerae among Workers of a Jute Mill in Kolkata, West Bengal, India. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2011, 29, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrick, T.; Ponnaiah, M.; Murhekar, M.V.; Jayaraman, Y.; David, J.K.; Vadivoo, S.; Joshua, V. Vibrio cholerae Outbreak Linked with Lack of Safe Water Supply Following a Tropical Cyclone in Pondicherry, India, 2012. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2015, 33, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Uthappa, C.K.; Allam, R.R.; Nalini, C.; Gunti, D.; Udaragudi, P.R.; Tadi, G.P.; Murhekar, M.V. An outbreak of Vibrio cholerae in Medipally village, Andhra Pradesh, India, 2013. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2015, 33, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reller, M.E.; Mong, Y.; Hoekstra, R.M.; Quick, R.E. Vibrio cholerae prevention with traditional and novel water treatment methods: An outbreak investigation in Fort-Dauphin, Madagascar. Am. J. Public Health 2001, 91, 1608–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutin, Y.; Luby, S.; Paquet, C. A large Vibrio cholerae outbreak in Kano City, Nigeria: The importance of hand washing with soap and the danger of street-vended water. J. Water Health 2003, 1, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kone-Coulibaly, A.; Tshimanga, M.; Shambira, G.; Gombe, N.T.; Chadambuka, A.; Chonzi, P.; Mungofa, S. Risk factor associated with Vibrio cholerae in Harare City, Zimbabwe, 2008. East Afr. J. Public Health 2010, 7, 311–317. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle, S.E.; Mba-Jonas, A.; Loharikar, A.; Fouché, B.; Peck, M.; Ayers, T.; Archer, W.R.; De Rochars, V.M.B.; Bender, T.; Moffett, D.B.; et al. Epidemic Vibrio cholerae in a Crowded Urban Environment, Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 2143–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahamud, A.S.; Ahmed, J.A.; Nyoka, R.; Auko, E.; Kahi, V.; Ndirangu, J.; Nguhi, M.; Burton, J.W.; Muhindo, B.Z.; Breiman, R.F.; et al. Epidemic Vibrio cholerae in Kakuma Refugee Camp, Kenya, 2009: The importance of sanitation and soap. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2012, 6, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobel, J.; Gomes, T.A.T.; Ramos, R.T.S.; Hoekstra, M.; Rodrigue, D.; Rassi, V.; Griffin, P.M. Pathogen-Specific Risk Factors and Protective Factors for Acute Diarrheal Illness in Children Aged 12–59 Months in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 38, 1545–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mugoya, I.; Kariuki, S.; Galgalo, T.; Njuguna, C.; Omollo, J.; Njoroge, J.; Kalani, R.; Nzioka, C.; Tetteh, C.; Bedno, S.; et al. Rapid Spread of Vibrio Vibrio cholerae O1 Throughout Kenya, 2005. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2008, 78, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, M.J.; Wamala, J.F.; Eyura, M.; Malimbo, M.; Omeke, M.E.; Mayer, D.; Lukwago, L. A Vibrio cholerae outbreak among semi-nomadic pastoralists in northeastern Uganda: Epidemiology and interventions. Epidemiol. Infect. 2012, 140, 1376–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chompook, P.; Todd, J.; Wheeler, J.G.; von Seidlein, L.; Clemens, J.; Chaicumpa, W. Risk factors for shigellosis in Thailand. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 10, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araya-Alpízar, C. Diagnóstico de clases latentes en tablas con frecuencias pequeñas o nulas. Rev. Pensam. Actual 2015, 10, 425–433. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld, P.F.; Henry, N.W. Latent Structure Analysis; Houghton-Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1968; pp. 1–294. [Google Scholar]

- Batool, N.; Dada, Z.A.; Shah, S.A. Developing tourist typology based on environmental concern: An application of the latent class analysis model. SN Soc. Sci. 2022, 2, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, N.W. Latent Structure Analysis; Weily: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Véliz-Capuñay, C. Clases latentes. In Análisis Multivariante: Métodos Estadísticos Multivariantes Para La Investigación; Chávez-Ceballos, C., Herrero, N., Rodríguez-Velázquez, J.P., Eds.; CENGAGE Learning: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2017; pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Hurtado, J.M.; Berbel-Pineda, J.M. Identification of Segments for Overseas Tourists Playing Golf in Spain: A Latent Class Approach. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 24, 652–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).