A Transdisciplinary Approach to Water Access: An Exploratory Case Study in Indigenous Communities in Chiapas, Mexico

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Approach

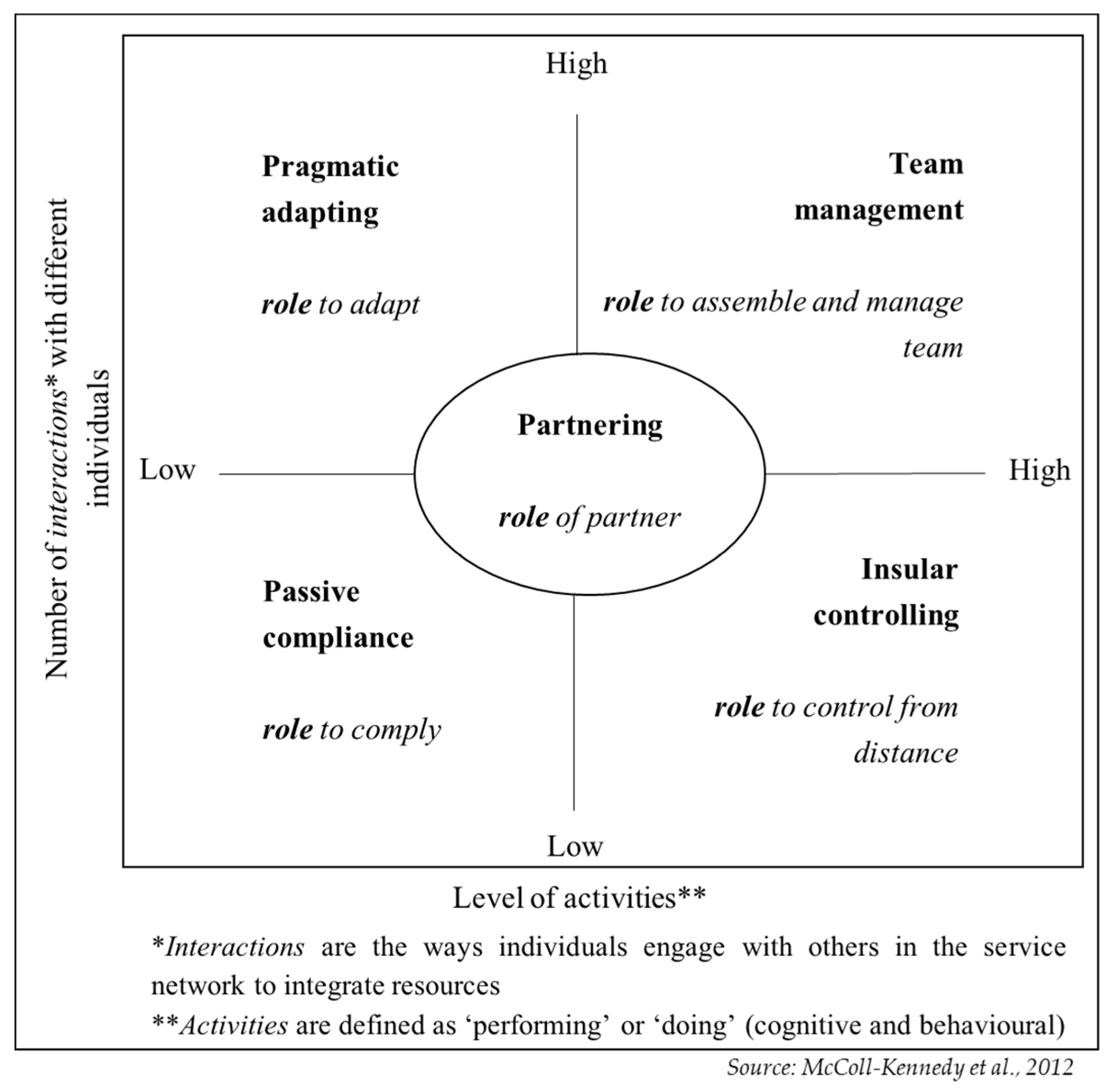

Service-Dominant (S-D) Logic and Water-Related Challenges

3. Research Setting and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Focus Groups

3.2.1. Indigenous Communities (ICs)

3.2.2. Key Stakeholders

3.3. Lead Author’s Observations

4. Findings

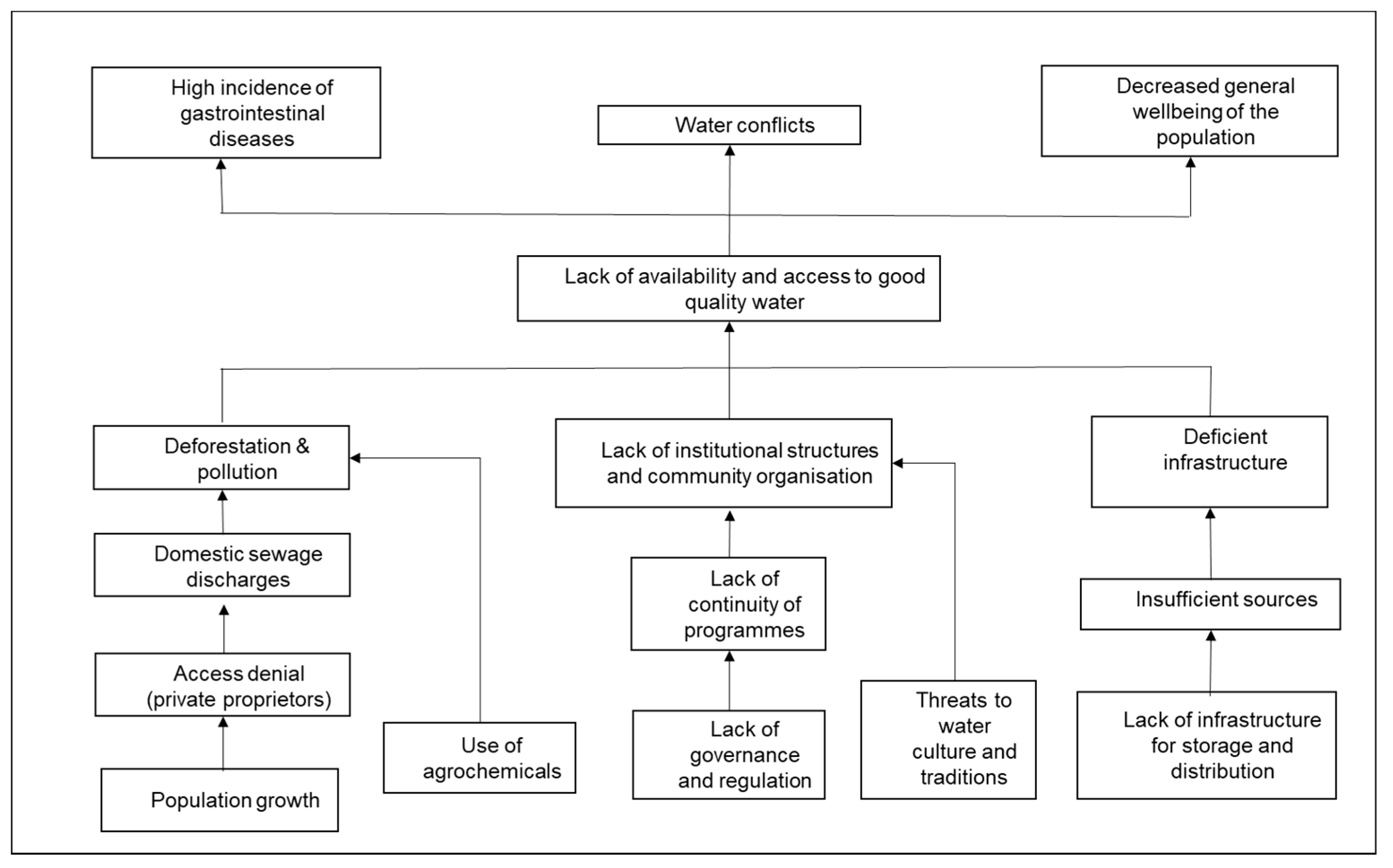

4.1. The Problem of Availability and Access to Clean Water

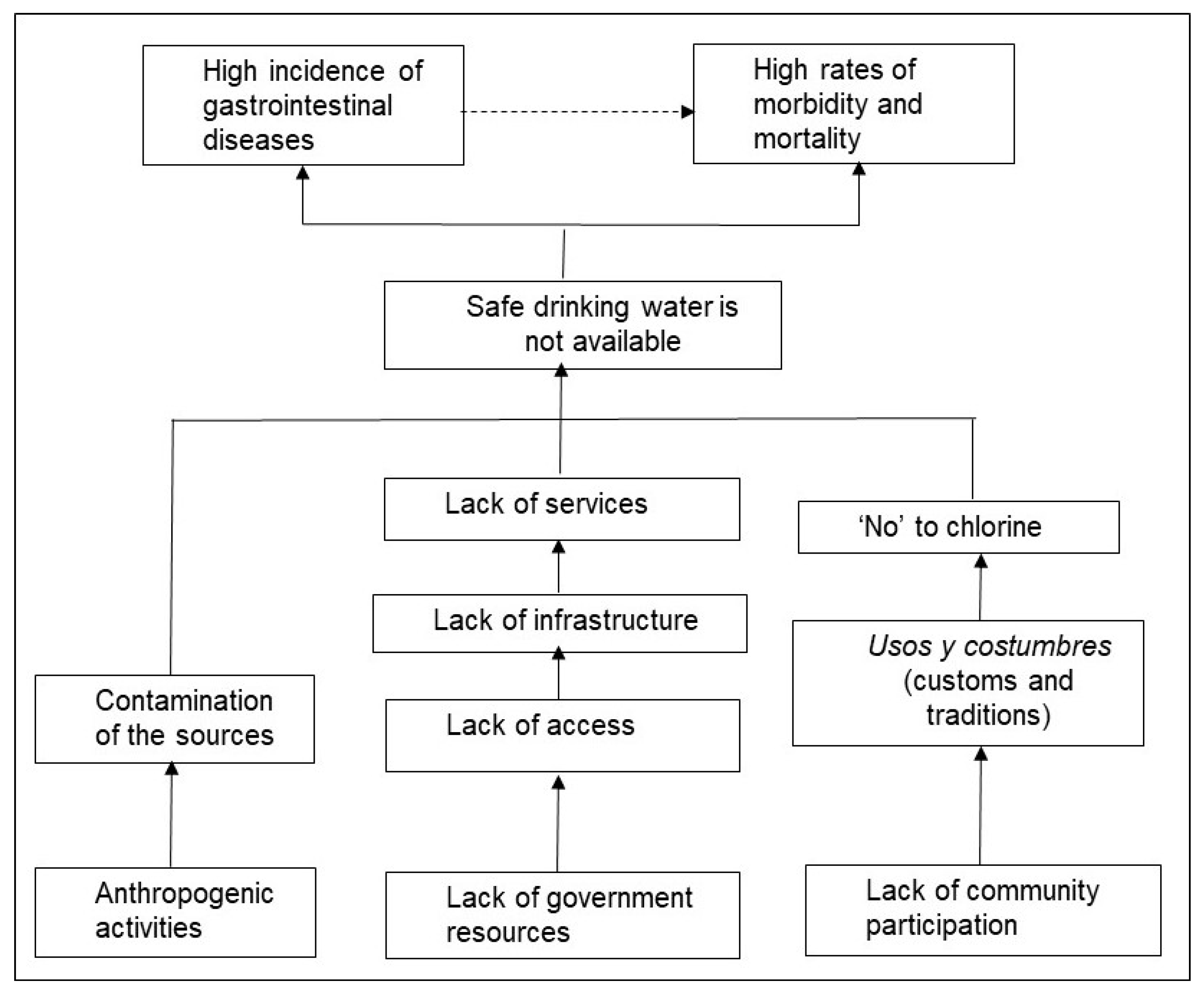

4.1.1. Indigenous Communities (ICs)

The stream is in a private source and the owner denies the access to it. We can’t do anything about it, he does not listen, and all he wants is the money. So, we can’t have piped water like many other communities and the authorities don’t do anything about it.(52-year-old male)

You see it all the time. People put waste in a lorry and they dump it in the streams because there hasn’t been any refuse collection for weeks.(35-year-old male)

The young people don’t participate in the community and they just don’t care much about water. They are not worried about not having clean water because they always carry bottled water or drink [fizzy drinks]. I just explain to people that water is better and healthier, and you can use it to make nice juices.(20-year-old male)

There is a tradition in our culture to protect our springs … our sources of water and we are happy when the rain comes because we know that there will be plenty of water … young people, they don’t see that, they just go to the shop and buy a bottle of mineral water.(36-year-old male)

People just drink water; they don’t want to drink safe water. They don’t see the danger of drinking any water. So, in order to change, you need to change people’s habits first.(45-year-old female)

4.1.2. Key Stakeholders

No-one in the communities would adopt such systems, while they leave a taste of chlorine in the water.(Health Authority)

4.1.3. Lead Author’s Observations

4.2. Cocreating Value for Water Access, Sustainability and Development

[…] considers the supernatural beings of the water sources, predominantly the ladies or mothers who inhabit them, and with whom community sostain (sic) a permanent relationship that promotes fisical (sic) as well as ritual caring for water and territory to be inherited to future generations.(italics in the original, p. 21)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. General Assembly Resolution. Transforming our World, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNGA. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly. 64/292. the Human Right to Water and Sanitation; A/RES/64/292; UNGA: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- WWAP. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2019: Leaving No-One Behind; UNESCO World Water Assessment Programme: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Statistics Division. UN Data. A World of Information. Mexico. Available online: http://data.un.org/en/iso/mx.html (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- PAHO. 2030 Agenda for Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Latin America and the Caribbean: A Look from the Human Rights Perspective; Pan American Health Organisation: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF/WHO. Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2000–2017. Special Focus on Inequalities; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and World Health Organization: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- CONAGUA. Estadísticas del Agua en México 2018 [Water Statistics for Mexico 2018]; Mexico, Gobierno de la Republica. Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, SEMARNAT; Comisión Nacional del Agua, CONAGUA: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas. Programa Especial de los Pueblos Indígenas 2014–2018 [National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples—’Special Programme for Indigenous Peoples 2014–2108’]; Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakar, I.R. Factors influencing household access to drinking water in Nigeria. Util. Policy 2019, 58, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleixo, B.; Pena, J.L.; Heller, L.; Rezende, S. Infrastructure is a necessary but insufficient condition to eliminate inequalities in access to water: Research of a rural community intervention in northeast Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 652, 1445–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, B.O.; Jimenez, F.d.P.A.; Perez, F.A. Measuring disparities in access to water based on the normative content of the human right. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 127, 741–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, C.A.; Pena, J.L. Water meters and monthly bills meet rural Brazilian communities: Sociological perspectives on technical objects for water management. World Dev. 2016, 84, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurber, M.C.; Warner, C.; Platt, L.; Slaski, A.; Gupta, R.; Miller, G. To promote adoption of household health technologies, think beyond health. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1736–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enengel, B.; Muhar, A.; Penker, M.; Freyer, B.; Drlik, S.; Ritter, F. Co-production of knowledge in transdisciplinary doctoral theses on landscape development—An analysis of actor roles and knowledge types in different research phases. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 105, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S.; Pohl, C.; Hering, J.G. Methods and procedures of transdisciplinary knowledge integration: Empirical insights from four thematic synthesis processes. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, T.; Maynard, C.; Carr, G.; Bruns, A.; Mueller, E.N.; Lane, S. A transdisciplinary account of water research. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2016, 3, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hering, J.G.; Hoffmann, S.; Meierhofer, R.; Schmid, M.; Peter, A.J. Assessing the societal benefits of applied research and expert consulting in water science and technology. GAIA 2012, 21, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.; Rondón-Sulbarán, J. Transdisciplinary research: Exploring impact, knowledge and quality in the early stages of a sustainable development project. World Dev. 2019, 122, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado-Jaramillo, C.H.; Chiu, M.; Arimany-Serrat, N.; Ferras, X.; Meijide, D. Identifying sustainability-value creation drivers for a company in the water industry sector: An empirical study. Water Resour. Manag. 2018, 32, 3961–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic 2025. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2017, 34, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacio-Mejía, L.S.; Rojas-Botero, M.; Molina-Vélez, D.; García-Morales, C.; González-González, L.; Salgado-Salgado, A.; Hernández-Ávila, J.E.; Hernández-Ávila, M. Overview of acute diarrheal disease at the dawn of the 21st century: The case of Mexico. Salud Publica Mex. 2019, 62, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prüss-Ustün, A.; Wolf, J.; Bartram, J.; Clasen, T.; Cumming, O.; Freeman, M.C.; Gordon, B.; Hunter, P.R.; Medlicott, K.; Johnston, R. Burden of disease from inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene for selected adverse health outcomes: An updated analysis with a focus on low- and middle-income countries. Int. J. Hygiene Environ. Health 2019, 222, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Palmer, M.; Richards, K. Enhancing water security for the benefits of humans and nature—the role of governance. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lusch, R.F.; Vargo, S.L.; O’Brien, M. Competing through service: Insights from service-dominant logic. J. Retail. 2007, 83, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsson, B.; Tronvoll, B.; Gruber, T. Expanding understanding of service exchange and value co-creation: A social construction approach. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Why “service”? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.D.; Vargo, S.L. Contextualization and value-in-context: How context frames exchange. Mark. Theory 2011, 11, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McColl-Kennedy, J.; Vargo, S.L.; Dagger, T.S.; Sweeney, J.C.; van Kasteren, Y. Health care customer value cocreation practice styles. J. Serv. Res. 2012, 15, 370–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Eversole, R. Rethinking the regions: Indigenous peoples and regional development. Reg. Stud. 2019, 53, 1509–1519. [Google Scholar]

- Boelens, R.; Chiba, M.; Nakashima, D. Water and Indigenous Peoples; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- WWAP. The United Nations World Water Development Report 1: Water for People Water for Life; UNESCO, World Water Assessment Programme; Berghahn Books: Paris, France; London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- González-Padrón, S.K.; Lerner, A.M.; Mazari-Hiriart, M. Improving water access and health through rainwater harvesting: Perceptions of an indigenous community in Jalisco, Mexico. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kelles-Viitanen, A. Custodians of Culture and Biodiversity. Indigenous Peoples Take Charge of their Challenges and Opportunities; IFAD, The United Nations International Fund for Agriculture and Development: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno de México. Programa Nacional de Desarrollo Social 2014–2018 [Mexican Government—’National Programme for Social Development 2014–2018’]; Secretaría de Desarrollo Social (Sedesol): Mexico City, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, M.N. El agua como derecho. Andamios Rev. Investig. Soc. 2018, 15, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONAGUA. Objetivos y Estrategias. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/busqueda?utf8=%E2%9C%93#gsc.tab=0&gsc.sort=&gsc.q=objetivos%20y%20estrategias (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Rodriguez, J.S. Rural water supply in Mexico. Cuad. Desarro. Rural. 2016, 13, 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, S.J.J. Agua Y Zonas Rurales, México. PROSSAPYS, Etapas I Y II; Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- CONEVAL. Diez Años de Medición de Pobreza Multidimensional en Mexico: Avances y Desafíos en Política Social. Medición de La Pobreza Serie 2008–2018 [Ten Years Measuring Multidimansional Poverty in Mexico: Progress and Challenges of Social Policy. Measuring Poverty Series 2008–2018]; CONEVAL, Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social: Mexico City, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann, R.; Cheston, T.; Santos, M.; Pietrobelli, C. Towards a prosperous and productive Chiapas: Institutions, policies, and public-private dialog to promote inclusive growth. Domest. Dev. Strateg. eJ. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- INEGI. México en Cifras. Chiapas. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/areasgeograficas/?ag=07 (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Gutiérrez, V.V.; Zapata, M.E.; Nazar, B.A.; Salvatierra, I.B.; Ruíz, d.O.C. Gobernanza en la gestión integral de recursos hídricos en las subcuencas Río Sabinal y Cañon del Sumidero en Chiapas, México. Agric. Soc. Desarro. 2019, 16, 159–181. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Estatal del Agua. El Agua en Chiapas; Instituto Estatal del Agua, Gobierno de Chiapas: Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Mexico, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- CONEVAL. Report of Poverty in Mexico 2010: The Country, its States and its Municipalities; CONEVAL, National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dansereau, E.; Schaefer, A.; Hernandez, B.; Nelson, J.; Palmisano, E.; Rios-Zertuche, D.; Woldeab, A.; Zuniga, M.P.; Iriarte, E.M.; Mokdad, A.H.; et al. Perceptions of and barriers to family planning services in the poorest regions of Chiapas, Mexico: A qualitative study of men, women, and adolescents. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murillo-Licea, D.; Soares-Moraes, D. Patrones de manejo y negociación por el agua en parajes tsotsiles de la ladera sur del volcán tsonte’vits, Chiapas, México. LiminaR Estud. Soc. Hum. 2017, 15, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- IDESMAC. Altos de Chiapas. Available online: http://www.idesmac.org.mx/index.php/altos-de-chiapas (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Flyvbjerg, B. Case Study. In Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry, 4th ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 169–203. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Aid Delivery Methods. Volume 1. Project Cycle Management Guidelines; EuropeAid Cooperation Office: Brussels, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kawulich, B. Participant observation as a data collection method. Forum Qual. Soz. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2005, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.B.; Earley, M.A. Reciprocity and constructions of informed consent: Researching with indigenous populations. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tauri, J.M. Research ethics, informed consent and the disempowerment of first nation peoples. Res. Ethics 2018, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt, K.M.; DeWalt, B.R. Participant Observation: A Guide for Fieldworkers; AltaMira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves López, N. Jalame´tik Ts´ajalsul Y Me´ Ats´am: “Señoras” Del Agua Dulce—Salada Entre Tsotsiles Y Tseltales De Los Altos De Chiapas. Rev. Agua Territ. Water Landsc. 2019, 14, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, A. Living Well: Ideas for Reinventing the Future. Third World Q. 2017, 38, 2600–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aged 18–25 Years (n = 5) | Aged 26–35 Years (n = 2) | Aged 36–45 Years (n = 2) | Aged 46–55 Years (n = 1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Group 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Group 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Group 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Sources | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indigenous Communities | Key Stakeholders | The Lead Author’s Observations | |

| Issues |

|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rondón-Sulbarán, J.; Balam, I.; Brennan, M. A Transdisciplinary Approach to Water Access: An Exploratory Case Study in Indigenous Communities in Chiapas, Mexico. Water 2021, 13, 1811. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13131811

Rondón-Sulbarán J, Balam I, Brennan M. A Transdisciplinary Approach to Water Access: An Exploratory Case Study in Indigenous Communities in Chiapas, Mexico. Water. 2021; 13(13):1811. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13131811

Chicago/Turabian StyleRondón-Sulbarán, Janeet, Ian Balam, and Michael Brennan. 2021. "A Transdisciplinary Approach to Water Access: An Exploratory Case Study in Indigenous Communities in Chiapas, Mexico" Water 13, no. 13: 1811. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13131811

APA StyleRondón-Sulbarán, J., Balam, I., & Brennan, M. (2021). A Transdisciplinary Approach to Water Access: An Exploratory Case Study in Indigenous Communities in Chiapas, Mexico. Water, 13(13), 1811. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13131811