The perception of the merits and pitfalls of tap water and bottled water constitute one of the more significant issues in domestic water use and management [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Health and safety concerns appear to play a major role in deciding which type of water source will be used as drinking water, since the quality of tap water continues to raise preoccupations among the public [

1,

4,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], with some countries asking for the derogation of European water quality standards [

12]. However, for most users, perceived quality is usually based on organoleptic properties, and especially flavor, although related factors, such as water hardness or the presence of chlorine, may be also relevant [

11,

13]. In sum, mistrust in tap water for drinking [

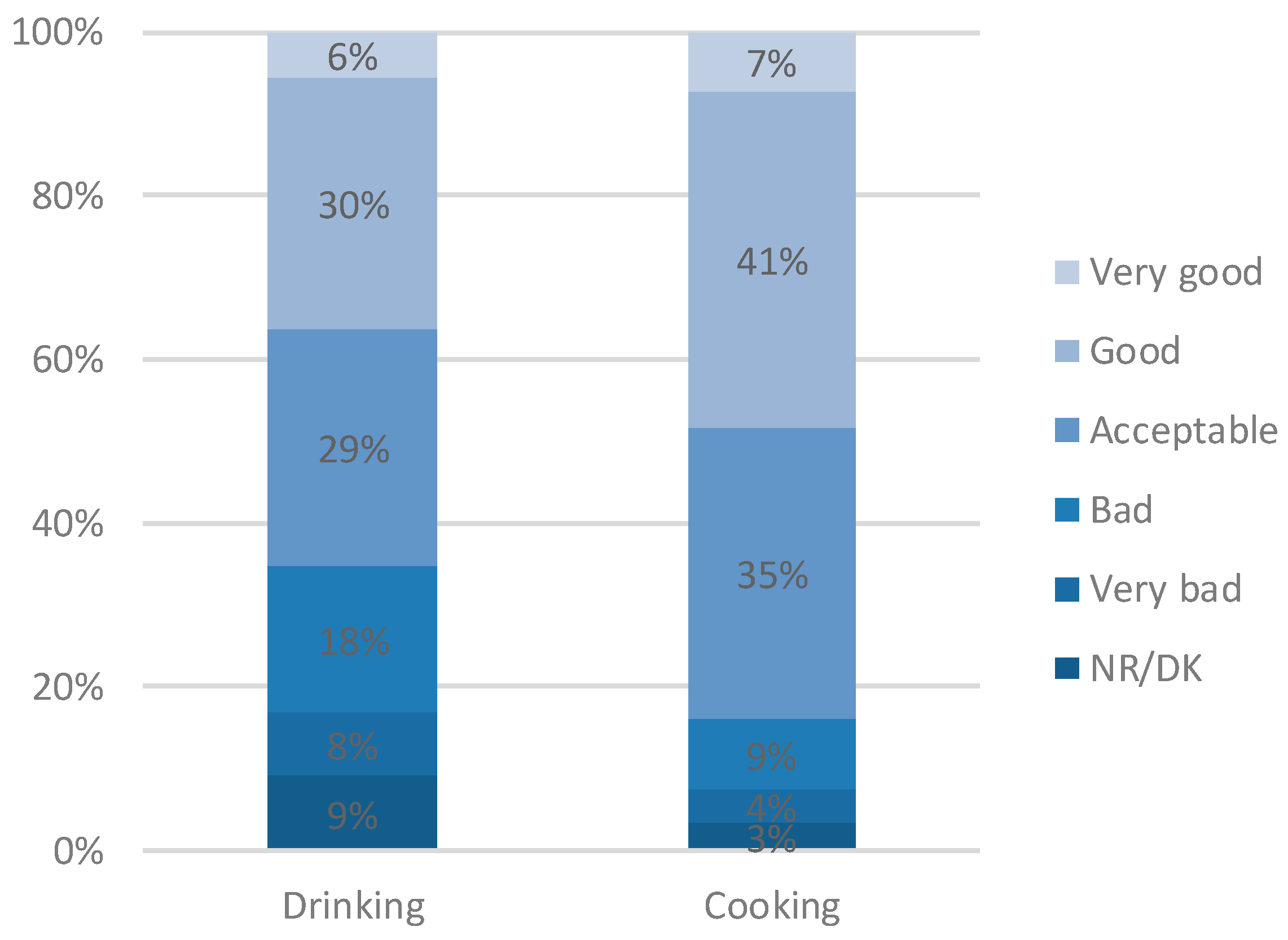

14], but in some cases for cooking as well [

15,

16], is still widespread, especially when risk communication fails to provide adequate messages [

17].

This article addresses household strategies for coping with poorly perceived tap water quality (either organoleptic or fear of harmful elements) in a developed country, and attempts to discern the relative importance of possible causes leading to the adoption of either bottled water or in-home treated tap water for drinking and cooking. Beyond data on the perception of tap water, the paper includes some household sociodemographic and urban data seldom discussed in the literature (for example, housing tenure or spatial variables) as potential drivers of bottled water use or in-home water treatments. The paper analyses the interactions between the use of bottled water and in-home water systems to provide a more complex picture of water flows in households, beyond the bottled water/tap water divide, and with significant implications for both the bottled water and the public and private water supply sectors.

Literature Review: Bottled Water and In-Home Water Treatment Systems; Complementary or Alternative?

Bottled water reigns supreme in the world beverage market, with its market distance from other refreshment beverages widening year after year. While there is not a consensus on the size of the global bottled water market, some figures point to market sizes in the early 2020s of around 300 billion euros [

11]. Figures for 2010 indicated a global annual consumption of 230 billion liters, with an annual growth above 6% [

11]. Middle- and high-income countries top the list of bottled water consumption per capita [

20]. In relative terms, Mexico and Thailand rank first in consumption (244 and 203 L/person/year respectively in 2015) followed by Italy, Germany, and the United States [

20]. In 2018, Spain registered a consumption of 2.6 billion liters of bottled water. In relative terms, the highest consumptions were found in the coastal and touristic regions of Canary and Balearic Islands, followed by Valencia and Catalonia. Apart from the weight of tourism use, the high concentration of bottled water consumption in the Mediterranean areas may have other causes, such as the historically poor quality (in the organoleptic sense) of water in certain areas, and the high hardness associated with the mostly calcareous nature of Mediterranean basins. Average domestic bottled water consumption in Spanish households was estimated in 61 L/person/year in 2018, representing half of the total consumption in the country. The rest of it can be attributed to consumption in bars, restaurants, and hotels, largely by tourists [

21].

Other than health and safety concerns regarding tap water, the success of bottled water is also related to its identification with certain lifestyles through marketing and branding [

11,

22]. Marketing and branding have played an important role in the steady increase in the bottled water trade, using the historically grounded cultural meanings of water, such as the power of nature, as well as the symbolism of the modern technology, and the conquest of water by purification systems [

22]. Part of the cultural power of water is rooted in the geographic and class associations of early brands of mineral water, which carried prestige and supposedly quasi magical healing powers.

Beyond these general drivers, it is important to shed light on how multiple socio-demographic and political factors, including age, gender, income, education, ethnicity, age, political ideology, the number of children in their household, previous experience, place of residence, and trust in the government affect the perception and preference of consumers towards bottled water [

15]. For instance, on average ethnic minorities in developed countries tend to consume more bottled water than the general population [

23,

24]. In this regard, a study in the USA found that minority children drank three times more bottled water than non-minority children [

25] (see also [

16]). This result is consistent with the broad literature on the legacy of residential segregation, and consequent variations in the quality of public services. In particular, the literature has identified predominantly African Americans and Hispanic neighborhoods as likely to experience poor tap water quality [

25]. Women also tend to consume more bottled water than men, in line with their higher risk awareness, in this case of tap water [

4]. Furthermore, the consumption of bottled water appears to be higher in households with more than three members and in households with children, possibly because of a “caregiver effect” [

26]. There is inconclusive evidence regarding income as a significant driver of bottled water consumption, with some studies showing that water bottled usage increases with household income [

10,

27], while in others, it appears insensitive to changes in income [

5].

Bottled water is also open to a variety of criticisms. First, in terms of quality, substantial differences between bottled water and tap water may be no longer present in many water supply systems. Modern water treatment plants can eliminate the organoleptic impacts common in the past. In fact, with just a simple treatment, blind tests indicate that consumers do not appreciate substantial differences between the two [

3]. In this respect, it must be borne in mind that an important share of bottled water in some contexts is no more than tap water treated to comply with the chemical, microbiological, and radiological safety requirements stipulated for pre-packaged water [

11]. Second, supplying costs, including energy or packaging [

11], remain another important issue with bottled water, which is between 240 and 10,000 times per liter more expensive than tap water [

28]. Third, plastic waste, most of which is accumulated in landfill, or contributing to the concentration of microplastics in the oceans [

29] is another important concern. The environmental costs of bottled water, including those related to energy needs, embedded CO

2 emissions, or waste production, are said to be 100 times higher than tap water [

14]. Fourth, environmental and human health concerns about bottled water are also rising, especially those related to plastic bottles and exacerbated by the current preoccupation with microplastics found in the water. A recent study in the US concluded that consumers of bottled water could be ingesting annually up to 90,000 plastic particles with the water, compared to 4000 for those drinking tap water [

30]. However, a recent report by the World Health Organization did not find significant health risks, although it also warned that more research mas needed [

31]. Likewise, the leaching of other chemicals, such as BPA or antimony in the water ingested [

32], remains an important issue as well.

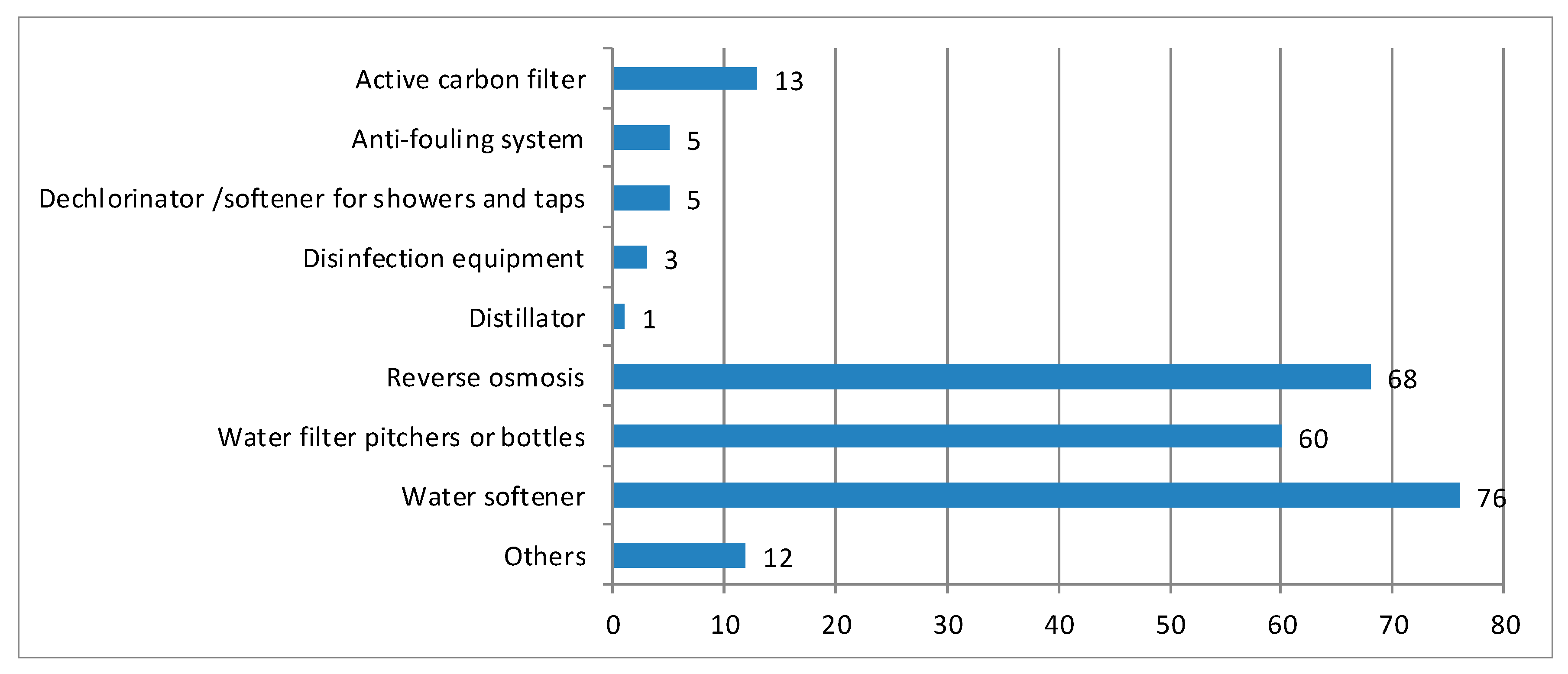

As mentioned in the introduction, a second strategy to address concerns about drinking water quality is the use of different in-home water treatment systems. These systems are divided into two main categories: Point of Entry (POE) systems, which are installed at the entrance of water into the home (e.g., water softeners, disinfection equipment, etc.), and Point of Use (POU) systems, which may be installed directly into any of the water sources existing at home (reverse osmosis, active carbon filter, etc.) [

33]. While POU systems have lower capacities and higher operational costs, they are less expensive and easier to install than POE. Of all these systems, pitchers or bottles dominate the market in terms of sales and value. The success of pitchers or bottles equipped with filters can be attributed to their low cost and the fact that they do not need any installation [

34].

In-home water treatment systems have been subject to special attention in developing countries where chronic problems in water quality leading to mortal diseases remain a serious cause of concern [

35,

36]. In contrast, empirical studies dealing with in-home water treatment systems in the developed world are less common despite a global market, growing from a value of UDS 19.9 billion in 2018, to an estimated value of USD 34.6 billion in 2026. Asia is projected to lead the market for POU technologies in the coming decades, followed by North America, which currently holds the majority of the market for POU systems, and Europe. Rapid urbanization and rising standards of living, coupled with concerns about water quality, explain the expansion of these technologies, especially in countries such as India and China [

37].

Given the fact that filtered tap water using in-home water treatment systems can be an effective substitute for bottled water consumption, some studies have compared three possible choices for drinking water consumption in households: unfiltered tap water, filtered tap water, and bottled water [

18,

27,

38]. While the consumption of bottled water is mainly linked to doubts about the safety of tap water, the consumption of filtered tap water is more related to sensory matters such as foul smelling and taste. Another interesting finding is that the purchase of filters is closely associated with income, unlike the case of bottled water, as noted above [

5]. It has to be noted that some of these in-home water treatments imply the increase of the household water and energy consumption, imposing higher costs to families. Still, an economic analysis developed in Barcelona showed that water treated by domestic reverse osmosis equipment was between 8 and 19 times cheaper than bottled water [

39]. Mackey et al. [

18], in their survey of alternatives to tap water in the United States, found that in-home treatment systems were more favored by females, the non-white population, young people, higher income groups, and higher education groups. Concerning the presence of children in households, Mackey et al. [

18] found that a much higher percentage of households with one or two children used these systems, compared to households with no children. However, the percentage of households with three or more children used these alternatives even less than households with no children. Thus, in the context of perceived low quality of the water supply service, richer households tend to have more often in-home water treatment systems than poorer households. At any rate, either for the installation of in-home water treatment systems, or for bottled water consumption, we do not know much about the role other factors, such as housing type or tenure. And perhaps most importantly, we do not know how both water flows interact with each other.