Holocene Evolution of the Burano Paleo-Lagoon (Southern Tuscany, Italy)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Regional Setting

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Geomorphology

3.2. Lithology

3.3. Geochronological Analysis

3.4. Sedimentological Analysis

3.5. Microfaunal Analysis

3.5.1. Foraminifera

3.5.2. Ostracoda

3.6. Palynological Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Geomorphology

4.2. Lithological Units

- Unit 1—Ocher and locally cemented quartz silty sands (zS) constitute this unit. Rare fine gravel with occasional centimetric pebbles and local plane-parallel lamination are present. The medium-sorted sediment shows uni or bimodal grain-size distribution. This unit outcrops along the inner edge of the depression and it was intercepted at the base of the BU4, 7 and 8, LB 2, 3 and 4 cores. The unit was crossed for about 3 m without ever reaching the bottom.

- Unit 2—It is a complex lithology unit mainly consisting of: soft peats, sandy mud (sM), mud (M), silt (Z) and muddy sand (mS) with abundant organic matter. Some thin levels with shell debris; are present more frequently in the lower part of the unit. They show a high silt content and are locally bioturbated. There are remains of Posidonia and undecomposed vegetal matter, occasional bivalve fragments and thin-shell gastropods. In the upper part, the unit is characterized by black-brown decametric thick soil outcropping into the depression. The unit was intercepted in the central and upper part of almost cores with a thickness ranging from 0.50 to over 3.0 m.

- Unit 3—It is made up of fine to medium-coarse greyish, more rarely yellowish, no diagenized feldspathic quartz sands (S). Sands are well sorted with a unimodal grain size distribution curve. Muddy sand (mS) and silty sand (zS) are more rarely present. Horizontal and medium-low angle plane-parallel laminations are present and centimetric to decimetric dark levels with femic minerals (in particular augite) were observed too. SEM and diffractometric analyses showed rare garnets, amphibole, pyrite, ilmenite, titanite and magnetite. There are locally present oblate or flattened pebbles, rare fine gravel levels and bivalves with complete shell or more frequently fragmented. This unit was intercepted mainly in the drills closest to the sea (where sometimes it represents the only body intercepted) with maximum thicknesses of about 7 m (LB2) and with more reduced thicknesses in the central ones; it is not present in the inner cores except BU10. Locally, this unit is interbedded to Unit 2 where it sometimes shows a high angle lamination.

- Unit 4—Whitish CaCO3 enriched silt (Z), scarce fine sand (S) and a bioclastic fraction characterize this unit. SEM and diffractometric analyses showed a composition constituted mainly of euhedral calcite crystals and subordinately secondary of gypsum. Downwards rare dark horizontal laminations were observed. This unit was intercepted in the upper part of the cores drilled in the central sector of the depression. The thickness is greater northward where it reaches about 2 m (LB1). In most parts of the cores, the whitish silt is interbedded with thin blackish peaty levels and in any case is always embedded in the Unit 2.

- Unit 5—This unit consists of medium to fine incoherent silty sand (zS) and muddy sand (mS). Moreover, there are horizontal plane-parallel laminations, rare gravel constituted of flat grains rare oxidized foraminifera and shell debris. This unit was intercepted, below Unit 3, in LB1 core for a thickness of about 7 m without ever reaching the bottom, and in BU3 core.

4.3. Paleovegetational Context

4.4. Bio-Indicators of the Aquatic Paleoenvironmental Conditions in Each Units

5. Discussion

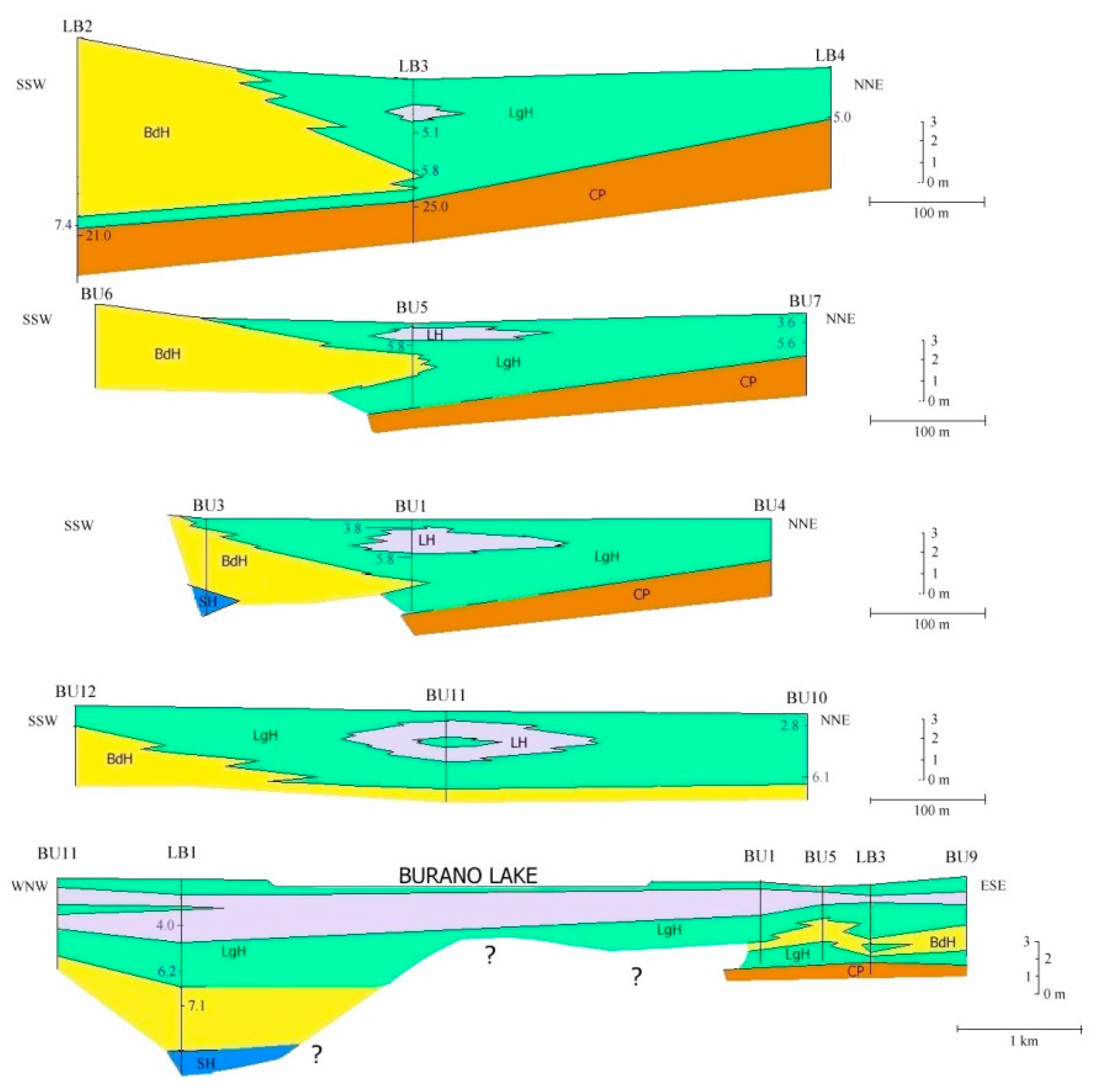

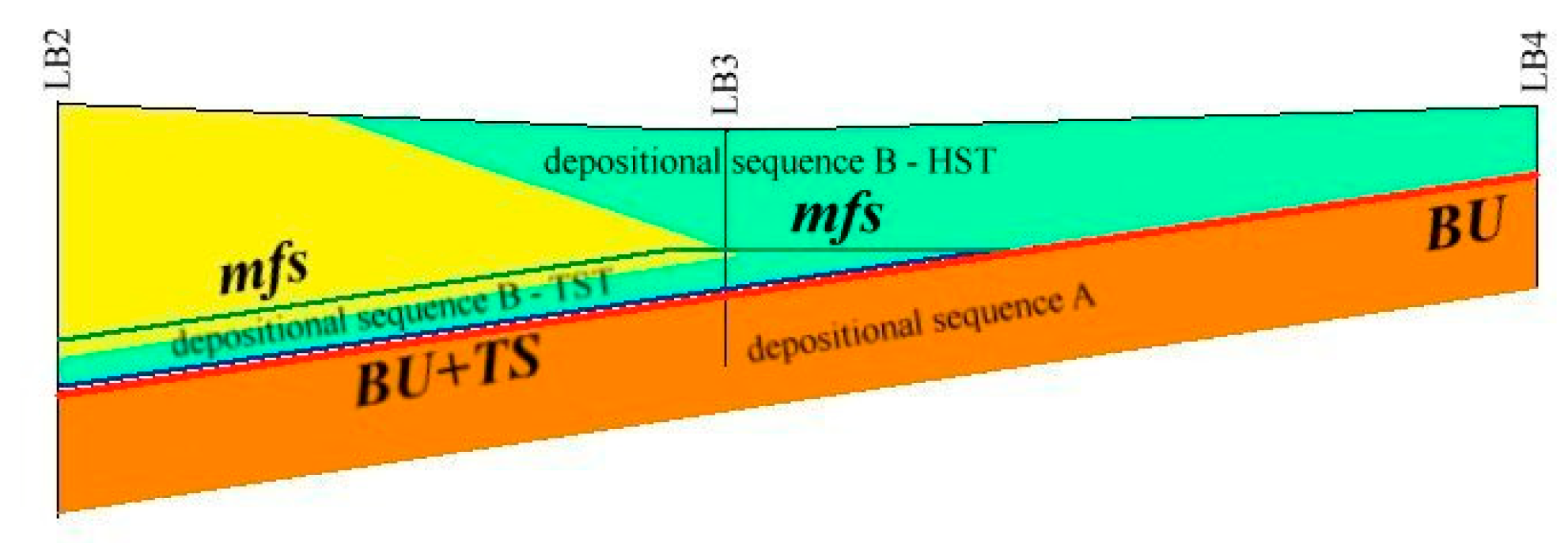

5.1. Facies and Reciprocal Stratigraphic Relationships (Figure 5):

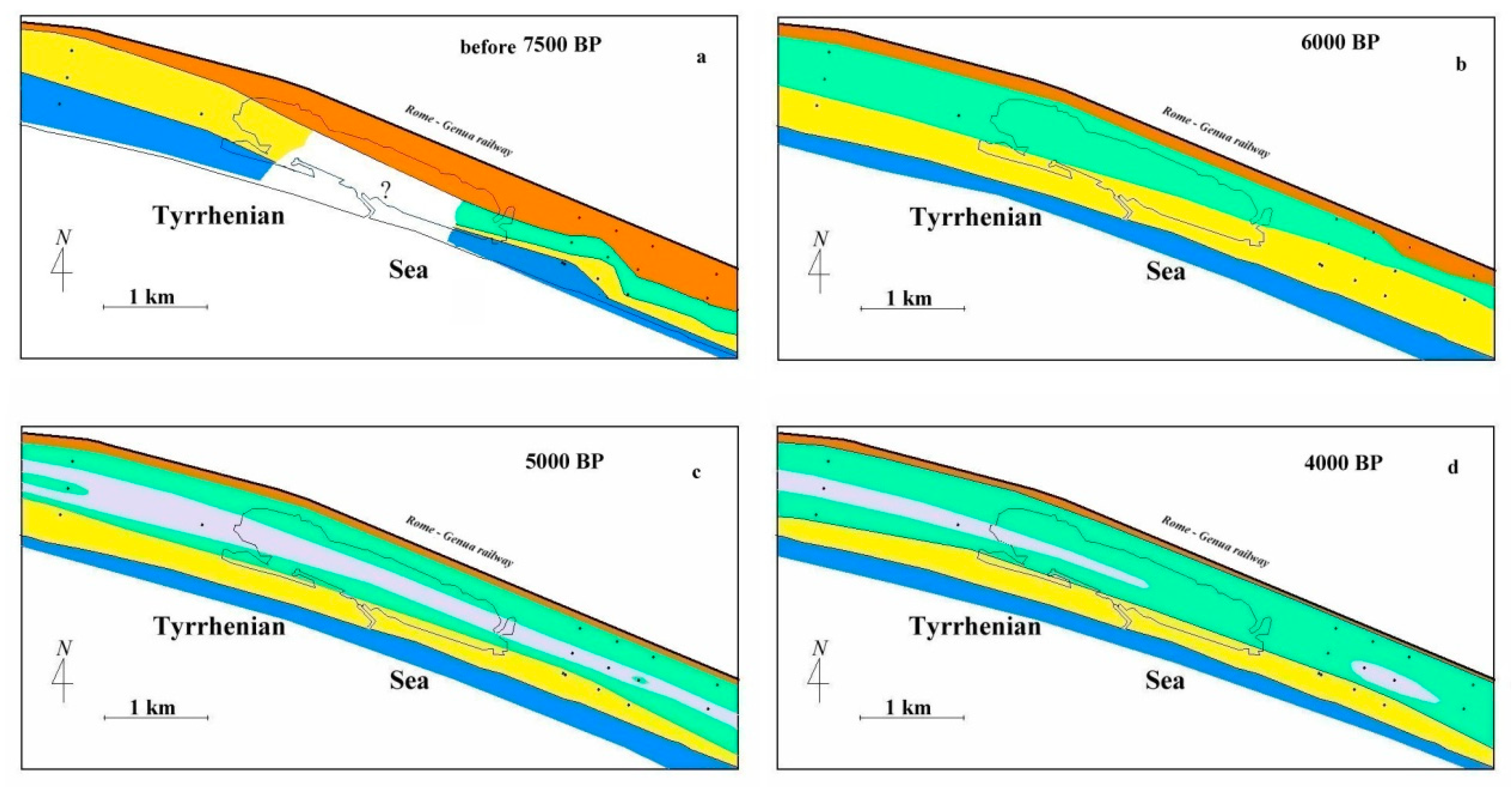

- Coastal Pleistocene facies (CP)—It is characterized by the lithological Unit 1 in which rare fragments of bivalves, oxidized shallow waters foraminifera and rare brackish and euryhaline ostracods have been found. The measured age varies between about 45 to about 20 ka BP. The lithology, the faunal content and datings, identify a generic coastal plain developed during the Upper Pleistocene.

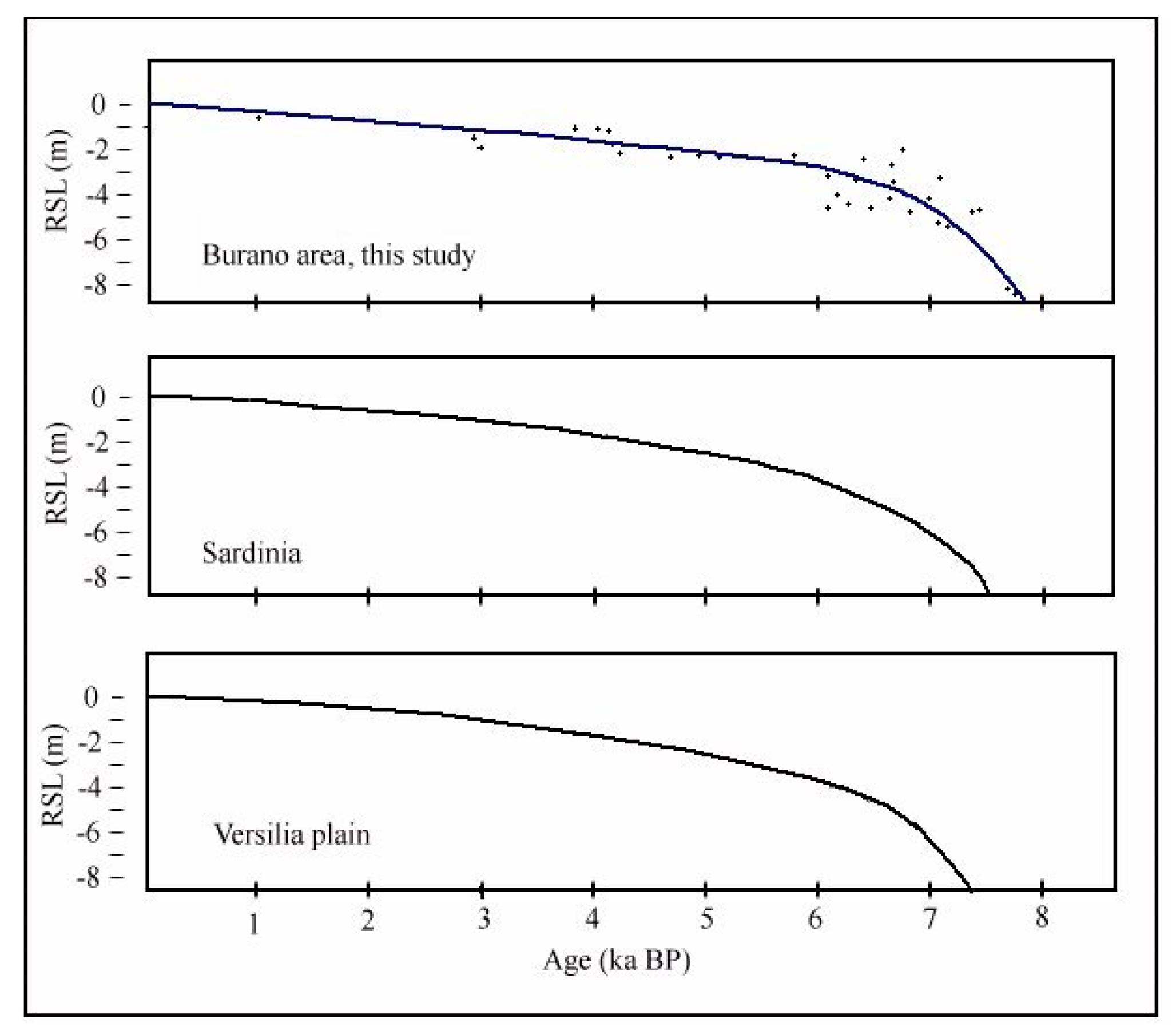

- Lagoon Holocene facies (LgH)—It includes sediments that refer prevalently to the Unit 2 in which the faunal content consists of predominant brackish and lagoonal/coastal taxa. Sometimes these taxa are accompanied by species more suitable for freshwater environment. It is confirmed by the absence of foraminiferal assemblages in the upper part of the unit. The decrease of marine dinocysts confirm a minor lagoon-sea connection in the time. According to the composition and stratigraphical distribution of dinocysts a main seawater input is documented close to about 8 ka BP (BU1 426 to 371 cm) whereas the marine influence progressively decreases until it disappears towards the more recent times. This facies develops mostly until 3.5 ka BP, even if locally, it is also present in more recent times (2.8–1.0 ka BP, Table 1). LgH facies is attributable to a coastal Holocene lagoon significantly influenced by the sea in the period before 6 ka BP even if phases of greater or less marine connection alternate over time. Using the calibrated ages in the BU10 core, where the organic sediments of this facies are more continuous and lacking clastic intercalations, the peat sedimentation rates were estimated (Figure 3a). These progressively decrease from 1.1 to 0.27 mm/year.

- Beach-dune Holocene facies (BdH)—It includes Unit 3 deposits characterized by the occurrence of prevalent marine bio-indicators; all previous evidences support the development of foreshore/dune, sand barrier environment and subordinately washover fans.

- Lacustrine Holocene facies (LH)—It corresponds to the whitish CaCO3 enriched Unit 4. The faunal component is essentially made up of freshwater gastropods and freshwater/low brackish ostracods. NPPs as a whole, confirm a prevalent freshwater environment; indeed, the main components of the NPPs assemblages are Cosmarium, indicative of prevalent freshwater conditions and Botryoccoccus, which thrives in fresh–brackish waters. Notably, their abundances (especially that of Cosmarium) indicates a bloom around 5770 year BP (in BU1). Such bloom may indicate a sudden change in one or more environmental parameters such as nutrients (e.g., phosphorus and nitrogen), temperature or pH. It is also necessary to understand if the phenomenon was natural or anthropic-induced. Cosmarium and Botryococcus proliferate in oligo-to mesotrophic conditions, and therefore a sudden eutrophication episode can be excluded. The absence of other taxa such as Pediastrum, aquatic algae commonly present in freshwater habitats rich in mineral and organic nutrients confirms the oligotrophic conditions. Desmids are sensitive organisms and act as an indicator of water quality, concentration of chemical oxygen demand, nitrate and turbidity; Botryococcus can dominates (or be present) in relatively extreme environments which prevents for example the occurrence of Pediastrum; it is often present when water is clear, oligotrophic, eventually dystrophic [74,75,76]. All this evidence permits to define a freshwater depositional basin with clear and oligotrophic waters. Moreover, the abundance of calcite suggests medium-high pH waters and probably microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation a phenomenon also associated with the so-called “Whitings” (e.g., [77,78]). The development of this facies starts after 6 ka BP and ends at about to 4 ka BP. The origin of this facies is not clear at present. Due to the absence of significant river inputs, it might assume a rise of fluids linked to the late hydrothermal phases of the Vulsino volcanism. Similar evidences were observed in the Specchio di Venere lake, a coastal basin in the volcanic island of Pantelleria (southern Sicily) [79].

- Shoreface Holocene facies (SH)—It is expressed by Unit 5. The presence of coastal malaco- ostracofauna partly reworked, shallow water oxidized foraminifera, as well as arenaceous pebbles and gravel levels, suggests that it is related to a shoreface environment. Locally (LB1), this environment could also be supplied by the remobilization of the Pleistocene sediments (CP facies) present at the inner edge of the depressed area.

5.2. Holocene Evolution

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kjerfve, B.; Magill, K.E. Geographic and hydrodynamic characteristics of shallow coastal lagoons. Mar. Geol. 1989, 88, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalrymple, R.W.; Leckie, D.A.; Tillman, R.W. Incised Valleys in time and space. SEPM Publ. 2006, 85, 343. [Google Scholar]

- Marco-Barba, J.; Holmes, J.A.; Mesquita-Joanes, F.; Miracle, M.R. The influence of climate and sea level change on the Holocene evolution of a Mediterranean coastal lagoon: Evidence from ostracod palaeoecology and geochemistry. Geobios 2013, 46, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, F.; Bozzano, F.; Cinti, F.R. Chronostratigraphic and lithologic feature soft the Tiber River sediments (Rome, Italy): Implications on the post-glacial sea-level rise and Holocene climate. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2013, 107, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milli, S.; D’Ambrogi, C.; Bellotti, P.; Calderoni, G.; Carboni, M.G.; Celant, A.; Di Bella, L.; Di Rita, F.; Frezza, V.; Magri, D.; et al. The transition from wave-dominated estuary to wave -dominated delta: The Late Quaternary stratigraphic architeture of Tiber River deltaic succession (Italy). Sediment. Geol. 2013, 284, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benallack, K.; Green, A.N.; Humphries, M.S.; Cooper, J.A.G.; Dladla, N.N.; Finch, J.M. The stratigraphic evolution of a large back-barrier lagoon system with a non-migrating barrier. Mar. Geol. 2016, 379, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolin, E.; Weschenfelder, J.; Cooper, A. Holocene Evolution of Patos Lagoon, Brazil. J. Coast. Res. 2019, 35, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dladla, N.N.; Green, A.N.; Cooper, J.A.G.; Humphries, M.S. Geological inheritance and its role in the geomorphological and sedimentological evolution of bedrock-hosted incised valleys, lake St Lucia, South Africa. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 222, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayewski, P.A.; Rohling, E.E.; Stager, J.C.; Karlen, W.; Maasch, K.A.; Meeker, L.D.; Meyerson, E.A.; Gasse, F.; Van Kreveld, S.; Holmgren, K.; et al. Holocene climate variability. Quat. Res. 2004, 62, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, C.; Fleury, T.J.; Raccasi, G.; Provansal, M.; Sabatier, F.; Bourcier, M. Evolution of The Rhône delta plain in the Holocene. Mar. Geol. 2005, 222, 235–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, R.P.; Mallinson, D.J.; Clunies, G.J.; Rey, A.; Culver, S.J.; Zaremba, N.; Leorri, E.; Mitra, S. Estuarine Responses to Long-Term Changes in Inlets, Morphology, and Sea Level Rise. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2019, 124, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotti, P. Sedimentologia ed evoluzione olocenica della laguna costiera un tempo presente alla foce del Tevere. In Proceedings of the Atti del X Congresso Della Associazione Italiana di Oceanologia e Limnologia, Alassio, Italy, 4–6 November 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Di Rita, F.; Celant, A.; Magri, D. Holocene environmental instability in the wetland north of the Tiber delta (Rome, Italy): Sea–lake–man interactions. J. Paleolimnol. 2010, 44, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraudi, C. The sediments of the ‘Stagno di Maccarese’ marsh (Tiber river delta, central Italy): A late-Holocene record of natural and human-induced environmental changes. Holocene 2011, 21, 1233–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotti, P.; Calderoni, G.; Di Rita, F.; D’Orefice, M.; D’Amico, C.; Esu, D.; Magri, D.; Preite Martinez, M.; Tortora, P.; Valeri, P. The Tiber River delta plain (central Italy): Coastal evolution and implications for the ancient Ostia Roman settlement. Holocene 2011, 21, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannuzi, S. La laguna di Ostia: Produzione del sale e trasformazione del paesaggio dall’età antica all’età moderna. Available online: http://www.efrome.it/publications/resurce-en-ligne.html (accessed on 25 November 2013).

- Vittori, C.; Mazzini, I.; Salomon, F.; Goiran, J.P.; Pannuzi, S.; Rossa, C.; Pellegrino, A. Palaeoenvironmental evolution of the ancient lagoon of Ostia Antica (Tiber delta, Italy). J. Archaeol. Sci. 2015, 54, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoli, L.; Raffi, R.; Baldassarre, A.M.; Bellotti, P.; Di Bella, L. New maps relative to the «Palude di Torre Flavia» (Central Tyrrhenian Sea-Italy) prone to severe coastal erosion. IJEGE 2019, 2, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- D’Orefice, M.; Graciotti, R.; Bertini, A.; Fedi, M.; Foresi, L.M.; Ricci, M.; Toti, F. Latest Pleistocene to Holocene environmental changes in the Northern Tyrrhenian area (central Mediterranean). A case study from southern Elba Island. AMQ 2020, 33, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Goiran, J.P.; Pavlopoulos, K.P.; Fouache, E.; Triantaphyllou, M.; Etienne, R. Piraeus, the ancient island of Athens: Evidence from Holocene sediments and historical archives. Geology 2011, 39, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, D.J.; Bernasconi, M.P. Holocene depositional pattern and evolution in Alexandria’s Eastern Harbor, Egypt. J. Coast. Res. 2006, 22, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, D.J.; Bernasconi, M.P. Sybaris-Thuri-Copia trilogy: Three delta coastal sites become landlocked. Méditerranée 2009, 112, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bellotti, P.; Caputo, C.; Dall’Aglio, P.L.; Davoli, L.; Ferrari, K. Human settlement in an evolvine landscape. Man-environment interaction in the Sibari Plain (Ionian Calabria). AMQ 2009, 22, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bini, M.; Brückner, H.; Chelli, A.; Pappalardo, M.; Da Prato, S.; Gervasini, L. Palaeogeographies of the Magra Valley coastal plain to constrain the location of the Roman harbour of Luna (NW Italy). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2012, 337, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorosi, A.; Bini, M.; Giacomelli, S.; Pappalardo, M.; Ribecai, C.; Rossi, V.; Sammartino, I.; Sarti, G. Middle to late Holocene environmental evolution of the Pisa plain (Tuscany, Italy) and early human settlements. Quat. Int. 2013, 303, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, E.J.; Marriner, N.; Morhange, C. Human influence and the changing geomorphology of Mediterranean deltas and coasts over last 6000 years: From progradation to destruction phase? Earth Sci. Rev. 2014, 139, 336–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghilardi, M.; Istria, D.; Curras, A.; Vacchi, M.; Contreras, D.; Vella, C.; Dussouillez, P.; Crest, Y.; Guiter, P.; Delanghe, D. Reconstructing the landscape evolution and the human occupation of the Lower Sagone River (Western Corsica, France) from the Bronze Age to the Medieval period. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2017, 12, 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaime, M.; Magne, G.; Bivolaru, A.; Gandouin, E.; Marriner, N.; Morhange, C. Halmyris. Geoarchaeology of a fluvial harbour on the Danube Delta (Dobrogea, Romania). Holocene 2018, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaime, M.; Marriner, N.; Morhange, C. Evolution of ancient harbours in deltaic contexts: A geoarchaeological typology. Earth Sci. Rev. 2019, 191, 1–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Regione Toscana. Carta Geologica Della Regione Toscana in Scala 1:10.000. 2015. Available online: http://www502.regione.toscana.it/geoscopio/cartoteca.html (accessed on 28 November 2014).

- Bartole, R. Caratteri sismostratigrafici, strutturali e paleogeografici della piattaforma continentale tosco-laziale; suoi rapporti con l’Appennino settentrionale. Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1990, 109, 599–622. [Google Scholar]

- Servizio Geologico d’Italia—Carta Geologica d’Italia alla scala 1:100.000—Foglio 135 “Orbetello”. 1968. Stab. L. Salomone, Roma. Available online: http://193.206.192.231/carta_geologica_italia/tavoletta.php?foglio=13501.02.2012 (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- Carmignani, L.; Decandia, F.A.; Fantozzi, P.L.; Lazzaretto, A.; Lotta, D.; Meccheri, M. Tertiary extensional tectonics in Tuscany (Northern Apennines, Italy). Tectonophysics 1994, 238, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartole, R. The North Tyrrhenian-Northern Apennines post-collisional system: Constrain for a geodynamic model. Terra Nova 1995, 7, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principe, C.; Malfatti, A.; Rosi, M.; Ambrosio, M.; Fagioli, M.T. Metodologia innovativa di carotaggio microstratigrafico: Esempio di applicazione alla tefrostratigrafia di prodotti vulcanici distali. Geol. Tec. Ambient. 1997, 4, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosio, M.; Dellomonaco, G.; Fagioli, M.T.; Giannini, F.; Pareschi, M.T.; Pignatelli, L.; Rosi, M.; Santacroce, R.; Sulpizio, R.; Zanchetta, G. Utilizzo di fioretto meccanico e carotiere microstratigrafico inguainante per la valutazione degli spessori e della stratigrafia delle coltri vulcanoclastiche soggette a fenomeni di colata rapida di fango. Geol. Tec. Ambient. 1999, 4, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Stuiver, M.; Polach, H.A. Discussion: Reporting of 14C data. Radiocarbon 1977, 19, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramsey, B. Oxcal V.3.10; Research Laboratory for Archaeology: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Preusser, F.; Degering, D.; Fuchs, M.; Hilgers, A.; Kadereit, A.; Klasen, N.; Krbetschek, M.R.; Richter, D.; Spencer, J. Luminescence dating: Basics, methods and applications. Quat. Sci. J. 2008, 57, 95–149. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, A.S.; Wintle, A.G. Luminescence dating of quartz using an improved single-aliquot regenerative-dose protocol. Radiat. Meas. 2000, 32, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, D.; Richter, A.; Dornich, K. Lexsyg—A new system for luminescence research. Geochronometria 2013, 40, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galbraith, R.F.; Roberts, R.G.; Laslett, G.M.; Yoshida, H.; Olley, J.M. Optical dating of single grains of quartz from Jinmium rock shelter, northern Australia. Part I: Experimental design and statistical models. Archaeometry 1999, 41, 339–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preusser, F.; Kasper, H.U. Comparison of dose rate determination using high-resolution gamma spectrometry and inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. Anc. tL 2001, 19, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Folk, R.L. Distinction between Grain Size and Mineral Composition in Sedimentary-Rocks Nomenclature. J. Geol. 1954, 62, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.W. Ecology and Applications of Benthic Foraminifera; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 1–426. ISBN 978-051-153-552-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, O.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analisys. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Loeblich, A.R., Jr.; Tappan, H. Foraminiferal Genera and Their Classification; Van Nostrand Reinhold Company: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 1–71. ISBN 978-1-4899-5760-3. [Google Scholar]

- Cimerman, F.; Langer, M. Mediterranean foraminifera. In Slovenska Akademija Znanosti Umetnosti, Academia Scientiarum Artium Slovenica; Classis IV: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1991; pp. 1–118. [Google Scholar]

- Sgarrella, F.; Moncharmont-Zei, M. Benthic foraminifera of the Gulf of Naples (Italy): Systematics and autoecology. Boll. Soc. Paleontol. Ital. 1993, 32, 145–264. [Google Scholar]

- Milker, Y.; Schmiedl, G. A taxonomic guide to modern benthic shelf foraminifera of the western Mediterranean Sea. Palaeontol. Electron. 2012, 15, 1–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WoRMS Editorial Board. World Register of Marine Species. Available online: http://www.marinespecies.orgatVLIZ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Vittori, C. Trajectoires temporelles des environnements fluvio-lagunaires littoraux de la péninsule italique et sociétés anciennes. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaduce, G.; Ciampo, G.; Masoli, M. Distribution of ostracoda in the Adriatic Sea. Pubbl. Stn. Zool. Napoli 1975, 40, 1–304. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaduce, G.; Masoli, M.; Pugliese, N. Ostracodi bentonici dell’alto Tirreno. Sci. Nat. Acta Biol. 1977, 54, 243–261. [Google Scholar]

- Athersuch, J.; Horne, D.J.; Whittaker, J.E. Marine and Brackish Water Ostracods (Superfamilies Cypridacea and Cytheracea): Key and Notes for Identification of Species; Synopsis of the British Fauna (New Series) 43; The Linnean Society of London and the Estuarine and Brackish-Water Sciences Association: Leiden, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Meisch, C. Freshwater ostracoda of Western and Central Europe. In Süsswasserfauna von Mitteleuropa 8/3; Schwoerbel, J., Zwick, P., Eds.; Spektrum Akademischer Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 1–522. ISBN 978-1-4020-6417-3. [Google Scholar]

- Faranda, C.; Gliozzi, E. The ostracod fauna of the Plio-Pleistocene Monte Mario succession (Roma, Italy). Boll. Soc. Paleontol. Ital. 2008, 47, 215–267. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann, R. Atlas Quartärer und Rezenter Ostrakoden Mitteldeutschlands; Altenburger Naturwissenschaftliche Forsc-hungen: Altenburg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Aiello, G.; Barra, D.; Parisi, R.; Isaia, R.; Marturano, A. Holocene benthic foraminiferal and ostracod assemblages in a paleo-hydrothermal vent system of Campi Flegrei (Campania, South Italy). Palaeontol. Electron. 2018, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, F.; Abad, M.; Galán, E.; González, I.; Aguilá, I.; Olías, M.; Gómez Ariza, J.L.; Cantano, M. The present environmental scenario of El Melah Lagoon (NE Tunisia) and its evolution to a future sabkha. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2006, 44, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salel, T.; Bruneton, H.; Lefèvre, D. Ostracods and environmental variability in lagoons and deltas along the north-western Mediterranean coast (Gulf of Lions, France and Ebro delta, Spain). Rev. Micropaléontologie 2016, 59, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbulla, D.; Pugliese, N.; Russo, A. Ostracods from the National Park of La Maddalena Archipelago (Sardinia, Italy). Boll. Soc. Paleontol. Ital. 2004, 43, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, F.; González-Regalado, M.L.; Baceta, J.I.; Menegazzo-Vitturi, L.; Pistolato, M.; Rampazzo, G.; Molinaroli, E. Los ostrácodos actuales de la laguna de Venecia (NE de Italia). Geobios 2000, 33, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, R.; Bobier, C.; Carbonel, P.; Tastet, J.P. Contribution à la connaissance des systèmes lagunaires en domaine méditerranéen: Les milieux actuels et les paléoenvironnements du lac de Ghar El Melh et de la sebkha de l’Ariana (Tunisie). Boll. Oceanol. Teor. Appl. 1985, 3, 167–195. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzini, I.; Rossi, V.; Da Prato, S.; Ruscito, V. Ostracods in archaeological sites along the Mediterranean coastlines: Three case studies from the Italian peninsula. In The Archaeological and Forensic Applications of Microfossils: A Deeper Understanding of Human Histo; Williams, M., Hill, T., Eds.; The Micropalaeontological Society, Special Publications. Geological Society: London, UK, 2017; pp. 121–142. ISBN 178-620-305-7. [Google Scholar]

- Triantaphyllou, M.V.; Kouli, K.; Tsourou, T.; Koukousioura, O.; Pavlopoulos, K.; Dermitzakis, M.D. Paleoenvironmental changes since 3000 BC in the coastal marsh of Vravron (Attica, SE Greece). Quat. Int. 2010, 216, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukousioura, O.; Dimiza, M.D.; Kyriazidou, E.; Triantaphyllou, M.V.; Syrides, G.; Aidona, E.; Vouvalidis, K.; Panagiotopoulos, I.; Papadopoulou, L. Environmental evolution of the Paliouras coastal lagoon in the eastern Thermaikos gulf (Greece) during Holocene. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debenay, J.P.; Guillou, J.J. Ecological Transitions Indicated by Foraminiferal Assemblages in Paralic Environments. Estuaries 2002, 25, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laut, L.; Silva, F.S.; Figueiredo, A.G., Jr.; Laut, V. Assembleias de foraminíferos e tecamebas associadas a análises sedimentológicas e microbiológicas no delta do rio Paraíba do Sul, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Pesqui. Geociências 2011, 38, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martins, A.M.V.; Zaaboub, N.; Aleya, L.; Frontalini, F.; Pereira, E.; Miranda, P.; Mane, M.; Rocha, F.; Laut, L.; El Bour, M. Environmental Quality Assessment of Bizerte Lagoon (Tunisia) Using Living Foraminifera Assemblages and a Multiproxy Approach. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belart, P.; Frontalini, F.; Laut, V.; Fortes, R.; Clemente, I.; Raposo, D.; Martins, V.; Lorini, M.L.; Rocha Fortes, R.; Laut, L. Living benthic Foraminifera from the Saquarema lagoonal system (Rio de Janeiro, southeastern Brazil). Check List 2017, 13, 1–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zonneveld, K.A.F.; Marret, F.; Versteegh, G.J.M.; Bogus, K.; Bonnet, S.; Bouimetarhan, I.; Crouch, E.; de Vernal, A.; Elshanawany, R.; Edwards, L.; et al. Geographic distribution of dinoflagellate cysts in surface sediments. Pangaea 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimiza, M.D.; Koukousioura, O.; Triantaphyllou, M.V.; Dermitzakis, M.D. Live and dead benthic foraminiferal assemblages from coastal environments of the Aegean Sea (Greece): Distribution and diversity. Rev. Micropaléontologie 2016, 59, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batten, D.J.; Grenfell, H.R. Green and blue-green algae. Palynol. Princ. Appl. 1996, 36, 205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Guy-Ohlson, D. Botryococcus as an aid in the interpretation of palaeoenvironment and depositional processes. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 1992, 71, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, R.V. Distribution of the palynomorph group: Phytoplankton subgroup, chlorococcale algae. In Sedimentary Organic Matter; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Alonso, M.J.; Montañez Hernández, L.E.; Sanchez Muñoz, M.A.; Franco, M.; Rubi, M.; Narayanasamy, R.; Balagurusamy, N. Microbially Induced Calcium carbonate Precipitation (MICP) and its potential in Bioconcrete: Microbiological and molecular concepts. Front. Mater. 2019, 6, 1–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, F.; Balci, N.; Guven, B. A modeling approach for calcium carbonate precipitation in a hypersaline environment: A case study from a shallow, alkaline lake. Ecol. Complex. 2019, 39, 100–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangemi, M.; Bellanca, A.; Borin, S.; Hopkinson, L.; Mapelli, F.; Neri, R. The genesis of actively growing siliceous stromatolites: Evidence from Lake Specchio di Venere, Pantelleria Island, Italy. Chem. Geol. 2010, 276, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posamentier, H.W.; Vail, P.R. Eustatic Controls on Clastic Deposition II: Sequence and Systems Tract Models. In Sea Level Change: An Integrated Approach; Wilgus, C.K., Hastings, B.S., Eds.; SEPM Publ.: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1988; pp. 125–154. ISBN 978-091-898-574-3. [Google Scholar]

- Posamentier, H.W.; Allen, G.P. Siliciclastic sequence stratigraphy—Concepts and applications. Sedimentol. Paleontol. 1999, 7, 210. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, N.; Brayshaw, D.; Kuzucuoğlu, C.; Perez, R.; Sadori, L. The mid-Holocene climatic transition in the Mediterranean: Causes and consequences. Holocene 2011, 21, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bini, M.; Zanchetta, G.; Perşoiu, A.; Cartier, R.; Català, A.; Cacho, I.; Dean, J.R.; Di Rita, F.; Drysdale, R.N.; Finnè, M.; et al. The 4.2 ka BP Event in the Mediterranean region: An overview. Clim. Past 2019, 15, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Currás, A.; Ghilardi, M.; Peche-Quilichini, K.; Fagel, N.; Vacchi, M.; Delanghe, D.; Dussouillez, P.; Vella, C.; Bontempi, J.M.; Ottaviani, J.C. Reconstructing past landscapes of the eastern plain of Corsica (NW Mediterranean) during the last 6000 years based on molluscan, sedimentological and palynological analyses. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2017, 12, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rita, F.; Fletcher, W.J.; Aranbarri, J.; Margaritelli, G.; Lirer, F.; Magri, D. Holocene forest dynamics in central and western Mediterranean: Periodicity, spatio-temporal patterns and climate influence. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Melis, R.T.; Depalmas, A.; Di Rita, F.; Montisa, F.; Vacchi, M. Mid to late Holocene environmental changes along the coast of western Sardinia (Mediterranean Sea). Glob. Planet. Chang. 2017, 155, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sadori, L.; Koutsodendris, A.; Panagiotopoulos, K.; Masi, A.; Bertini, A.; Combourieu-Nebout, N.; Francke, A.; Kouli, K.; Joannin, S.; Mercuri, A.M.; et al. Pollen data of the last 500 ka BP at Lake Ohrid (south-eastern Europe). PANGAEA. Supplement to 2016, Pollen-based paleoenvoronmental and paleoclimatic change at Lake Ohrid (south-eastern Europe) during the past 500 ka. Biogeosciences 2018, 13, 1423–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lambeck, K.; Antonioli, F.; Anzidei, M.; Ferranti, L.; Leoni, G.; Scicchitano, G.; Silenzi, S. Sea level change along the Italian coast during the Holocene and projections for the future. Quat. Int. 2011, 232, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacchi, M.; Ghilardi, M.; Melis, R.T.; Spada, G.; Giaime, M.; Marriner, N.; Lorscheid, T.; Morhange, C.; Burjachs, F.; Rovere, A. New relative sea-level insights into the isostatic history of the Western Mediterranean. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2018, 201, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolini, C.; Corda, L.; D’Alessandro, L.; La Monica, G.B.; Regini, E. Studi di Geomorfologia costiera: III—Il tombolo di Feniglia. Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1979, 96, 117–157. [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista, S.; Full, W.E.; Tortora, P. Provenance and dispersion of fluvial, beach and shelf sands in the bassa Maremma coastal system (central Italy): An integrated approach using Fourier shape analysis, grain size and seismic data. Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1996, 115, 195–217. [Google Scholar]

| Ecological Groups | Taxa (Binomial Nomenclature) |

|---|---|

| Freshwater to low brackish | Candona sp. |

| Candona angulatata | |

| Darwinula stevensoni | |

| Herpetocypris sp. | |

| Heterocypris salina | |

| Ilyocypris sp. | |

| Limnocythere inopinata | |

| Paralimnocythere sp. | |

| Pseudocandona sp. | |

| Brackish | Cyprideis torosa |

| Loxoconcha elliptica | |

| Lagoon/coastal | Loxoconcha sp. |

| Xestoleberis communis | |

| Xestoleberis dispar | |

| Phytal coastal | Aurila sp. |

| Aurila woodwardii | |

| Bairdia mediterranea | |

| Callistocythere pallida | |

| Cushmanidea turbida | |

| Cytheretta sp. | |

| Cytheridea neapolitana | |

| Hiltermannicythere rubra | |

| Leptocythere sp. | |

| Leptocythere bacescoi | |

| Leptocythere cf. ramosa | |

| Leptocythere fabaeformis | |

| Microcytherura angulosa | |

| Microcytherura fulva | |

| Neocytherideis fasciata | |

| Neocytherideis (Sahnia) subulata | |

| Paracytheridea depressa | |

| Procytherideis (Neocytherideis) subspiralis | |

| Sagmatocythere littoralis | |

| Semicytherura sp. | |

| Semicytherura aff. rara | |

| Semicytherura amorpha | |

| Semicytherura incongruens | |

| Semicytherura sulcata | |

| Urocythereis favosa | |

| Marine | Carinocythereis whitei Costa punctatissima |

| Cytheropteron latum Eucythere curta | |

| Eucytherura angulata | |

| Jugosocythereis sp. | |

| Paracytherois mediterranea | |

| Paradoxostoma bradyi |

| Sample Identifier | Core # (Depth in Core, m) | Material | Conventional 14C Age (Year BP) | Calibrated Age (Calibrated Year BP) | δ 13C(2) (‰, vs. SMOW (Standard Mean Ocean Water)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rome-2334 | BU-1 (0.45–056) | sandy peat | 3775 ± 40 | 4200–4080 | −21.7 |

| Rome-2335 | BU-1 (1.82–1.89) | clay peat | 5770 ± 40 | 6405–6305 | −26.0 |

| Rome-2336 | BU-1 (3.10–3.19) | silt peat | 5860 ± 40 | 6740–6630 | −24.8 |

| Rome-2337 | BU-1 (3.59–3.64) | clay peat | 7940 ± 50 | 8980–8690 | −23.1 |

| Rome-2338 | BU-4 (0.50–0.60) | peat debris | 1010 ± 40 | 960–850 | −23.7 |

| Rome-2339 | BU-4 (1.0–1.1) | peat level | 3570 ± 40 | 4090–3920 | −25.0 |

| Rome-2340 | BU-4 (1.75–1.85) | clay peat | 5940 ± 50 | 6860–6670 | −25.8 |

| Rome-2341 | BU-5 (0.98–1.08) | peat debris | 5860 ± 45 | 6740–6570 | −23.4 |

| Rome-2342 | BU-5 (1.44–1.54) | silt clay | 6280 ± 50 | 7270–7090 | −24.9 |

| Rome-2342● | BU-7 (0.50–0.60) | peat level | 3550 ± 40 | 3900–3720 | −22.5 |

| Rome-2343 | BU-7 (1.44–1.57) | clay peat | 5620 ± 45 | 6450–6310 | −23.2 |

| Rome-2349 | BU-10 (0.50) | peat level | 2790 ± 40 | 2950–2840 | −22.9 |

| Rome-2360 | BU-10 (1.00) | peat level | 4320 ± 40 | 4970–4830 | −24.1 |

| Rome-2364 | BU-10 (1.50) | peat level | 4840 ± 40 | 5620–5480 | −22.5 |

| Rome-2361 | BU-10 (2.00) | peat level | 5310 ± 40 | 6270–5990 | −24.1 |

| Rome-2365 | BU-10 (2.50) | peat level | 5840 ± 40 | 6650–6560 | −22.6 |

| Rome-2350 | BU-10 (3.00) | peat level | 6115 ± 40 | 7160–6890 | −25.0 |

| Rome-2348 | BU-11 (1.31–1.46) | clay peat | 3830 ± 35 | 4290–4150 | −23.4 |

| Rome-2347 | BU-11 (2.83–2.97) | silty peat | 5270 ± 40 | 6170–5940 | −24.3 |

| Rome-2346 | BU-11 (3.53–3.67) | clay peat | 6445 ± 45 | 7430–7320 | −25.1 |

| Rome-2344 | BU-12 (0.50) | peat level | 3700 ± 40 | 4090–3930 | −23.5 |

| Rome-2345 | BU-12 (1.00) | peat level | 4560 ± 45 | 5320–5050 | −24.2 |

| Lyon-14228(sacA-49736) | LB1 (0.70) | Wood | Modern | Modern | Unavailable |

| Lyon-14223(sacA-49731) | LB1 (1.75–1.78) | Plant material | Modern | Modern | Unavailable |

| Lyon-15107(sacA-53026) | LB1 (1.93–1.96) | Plant material | Modern | Modern | Unavailable |

| Lyon-14224(sacA-49732) | LB1 (2.57) | Charcoal | 4060 ± 30 | 4779–4446 | Unavailable |

| Lyon-15109(sacA-53028) | LB1 (3.64–3.71) | Wood | 6180 ± 30 | 7159–7021 | Unavailable |

| Lyon-15110(SacA-53029) | LB1 (3.93–3.96) | Wood | 6200 ± 30 | 7166–7026 | Unavailable |

| Lyon-14226(sacA-49734) | LB1 (4.25–4.28) | Wood | 6155 ± 35 | 7157–7001 | Unavailable |

| Lyon-15117(SacA-53036) | LB1 (5.35–5.40) | Wood | 7945 ± 35 | 8974–8659 | Unavailable |

| Lyon-15108(sacA-53027) | LB1 (5.47) | Posidonia | 7095 ± 40 | 7616–7532 | Unavailable |

| Lyon-14227(sacA-49735) | LB1 (5.56–5.62) | Posidonia | 7190 ± 40 | 7691–7601 | −14.66 |

| Lyon-15111(sacA-53030) | LB1 (7.13) | Wood | 6640 ± 30 | 7568–7506 | Unavailable |

| Lyon-15112(SacA-53031) | LB2 (7.67–7.70) | Posidonia | 7275 ± 35 | 7779–7685 | Unavailable |

| Lyon-14229(sacA-49737) | LB2 (7.78–7.81) | Posidonia | 7350 ± 40 | 7670–7458 | −14.51 |

| Lyon-14231(sacA-49739) | LB3 (0.40-0.43) | Organic matter | 2775 ± 30 | 2925–2802 | −26.14 |

| Lyon-14230(sacA-49738) | LB3 (0.72–0.75) | Plant material | Modern | Modern | Unavailable |

| Lyon-15113(SacA-53032) | LB3 (1.03–1.06) | Shell | 5095 ± 30 | 5908-5761 | Unavailable |

| Lyon-14232(sacA-49740) | LB3 (3.06–3.09) | Posidonia | 5655 ± 35 | 6114–5991 | −14.13 |

| Lyon-15118(SacA-53037) | LB3 (3.12) | Posidonia | 5770 ± 30 | 6249–6171 | Unavailable |

| Lyon-15119(SacA-53038) | LB3 (3.30–3.34) | Wood | 5775 ± 30 | 6637–6541 | Unavailable |

| Lyon-15114(SacA-53033) | LB3 (3.44–3.48) | Charcoal | 6500 ± 30 | 7460–7336 | Unavailable |

| Lyon-15115(SacA-53034) | LB3 (3.86–3.89) | Shell | 6345 ± 30 | 6862–6763 | Unavailable |

| Lyon-14233(sacA-49741) | LB3 (4.33–4.39) | Charcoal | 6335 ± 35 | 7316–7182 | Unavailable |

| Lyon-14234(sacA-49742) | LB4 (1.00–1.03) | Plant material | 1085 ± 35 | 1045–963 | Unavailable |

| Lyon-15116(SacA-53035) | LB4 (1.12–1.15) | Plant material | 5190 ± 30 | 5987–5918 | Unavailable |

| Lyon-14235(sacA-49743) | LB4 (1.18–1.21) | Wood | 4970 ± 30 | 5727–5657 | Unavailable |

| Sample | Depth (cm) | K (Bq/kg) | Th (Bq/kg) | U (Bq/kg) | Wmeas (%) | Weff (%) | D-Q (Gy ka−1) | Grain size (µm) | N | Od | De OSL (Gy) | Age OSL (ka) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB2-1 | 840 | 1320 ± 80 | 75.0 ± 4.9 | 46.4 ± 2.8 | 15.4 | 20 ± 5 | 5.22 ± 0.40 | 150–200 | 24 | 0.28 | 118.86 ± 7.52 | 22.8 ± 1.7 |

| LB2-2 | 1115 | 1580 ± 160 | 69.9 ± 3.9 | 55.0 ± 3.0 | 13.0 | 20 ± 5 | 5.92 ± 0.47 | 150–200 | 25 | 0.22 | 276.15 ± 14.01 | 46.7 ± 3.7 |

| LB3-1 | 478 | 1400 ± 80 | 68.3 ± 3.8 | 47.1 ± 2.9 | 12.5 | 20 ± 5 | 5.28 ± 0.31 | 200–250 | 27 | 0.17 | 142.98 ± 5.89 | 27.1 ± 1.6 |

| LB3-2 | 585 | 1340 ± 130 | 67.2 ± 3.9 | 46.1 ± 2.7 | 13.7 | 20 ± 5 | 5.09 ± 0.44 | 200–250 | 21 | 0.25 | 193.97 ± 12.42 | 38.1 ± 3.3 |

| LB4 | 210 | 1470 ± 120 | 96.1 ± 5.8 | 64.1 ± 4.0 | 11.6 | 20 ± 5 | 6.26 ± 0.33 | 150–200 | 24 | 0.60 | 70–400 | 12–64 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Orefice, M.; Bellotti, P.; Bertini, A.; Calderoni, G.; Censi Neri, P.; Di Bella, L.; Fiorenza, D.; Foresi, L.M.; Louvari, M.A.; Rainone, L.; et al. Holocene Evolution of the Burano Paleo-Lagoon (Southern Tuscany, Italy). Water 2020, 12, 1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12041007

D’Orefice M, Bellotti P, Bertini A, Calderoni G, Censi Neri P, Di Bella L, Fiorenza D, Foresi LM, Louvari MA, Rainone L, et al. Holocene Evolution of the Burano Paleo-Lagoon (Southern Tuscany, Italy). Water. 2020; 12(4):1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12041007

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Orefice, Maurizio, Piero Bellotti, Adele Bertini, Gilberto Calderoni, Paolo Censi Neri, Letizia Di Bella, Domenico Fiorenza, Luca Maria Foresi, Markella Asimina Louvari, Letizia Rainone, and et al. 2020. "Holocene Evolution of the Burano Paleo-Lagoon (Southern Tuscany, Italy)" Water 12, no. 4: 1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12041007

APA StyleD’Orefice, M., Bellotti, P., Bertini, A., Calderoni, G., Censi Neri, P., Di Bella, L., Fiorenza, D., Foresi, L. M., Louvari, M. A., Rainone, L., Vittori, C., Goiran, J.-P., Schmitt, L., Carbonel, P., Preusser, F., Oberlin, C., Sangiorgi, F., & Davoli, L. (2020). Holocene Evolution of the Burano Paleo-Lagoon (Southern Tuscany, Italy). Water, 12(4), 1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12041007