1. Introduction

The concept of water sensitive cities refers to water systems that are planned, designed and managed to enhance a city’s liveability, resilience, sustainability and productivity [

1]. Water sensitive cities bring together integrated urban water management (IUWM) and water sensitive urban design (WSUD) approaches. For cities to transition to water sensitive futures, it has been recognised that community support is critical and communities have a key role to play in long-term planning [

1,

2].

In this paper, we contribute knowledge about the value of community participation in new collaborative water planning processes [

3]. Natural resource management has been identified as a ‘wicked problem’ because it involves particularly complex, open-ended and intractable issues where the definition of the problem and preferred solutions are strongly contested, as is often the case in contemporary water management. Collaborative planning processes have been proposed as useful in addressing ‘wicked problems’ [

4,

5]. As recent scholarship has argued, a holistic and process-oriented approach that is adaptive, participatory, and transdisciplinary is necessary for tackling complex ‘wicked’ problems [

3,

6,

7]. These approaches involve process cycles where ‘communication, perspective sharing, social learning, negotiation, and the development of adaptive strategies’ (p6) are prioritised to develop long-term environmental plans that are accepted by diverse professional and community stakeholders [

5]. Stakeholder engagement has long been recognised as an important concept in environmental governance but it has been given new prominence with the advent of new collaborative approaches to policy making and planning [

4,

5,

8,

9,

10].

In the water field, collaborative processes are gaining traction. For example, co-management of water resources by users has been shown to be effective and beneficial in many settings [

11]. Research has found that when citizens are genuinely involved in decision making, self-regulation and compliance is more likely than if an external authority imposes rules [

10,

12]. Past research has also shown that open and transparent communication processes between water professionals and community members are important in water planning processes [

3,

13]. When these are not present, there can be a loss of community confidence and decision making can be delayed [

13]. For example, in Brownhill Creek in South Australia, poor community engagement led to a three-year delay to decision making in the catchment; however, a change in management approach and more careful and respectful community engagement with a local environment and heritage action group led to subsequent positive outcomes [

13].

The critical role of community engagement and collaboration is also evident in the sustainability transitions literature where it is proposed that highly engaged ‘community champions’ can play a crucial role alongside professionals in leading change [

14]. With deeper understanding of the issues of climate change and the need for water sensitive solutions, communities can become important advocates, promoting social learning and diffusion of practices across their personal and professional networks [

15,

16]. Yet involving community members in participatory processes is complex and challenging, and skilled facilitation and trust have been shown to be important elements [

1,

4,

14,

17].

The aim of this study was to explore and assess how community members could best participate in a long-term sustainable water envisioning and planning process [

18]. We sought to understand the potential value that ‘community champions’, that is, motivated community members who self-select to participate in consultation processes, can have in driving transition actions towards a water vision. In this paper, we discuss the process and contribution community members made to the collaborative vision for water sensitive Bendigo, illustrated in

Figure 1.

2. Materials and Methods

This study involved a series of workshops, interviews and focus groups with key professional and community stakeholders to generate a long-term vision for a water sensitive Bendigo. Over an 8-month time period, participants were invited to collaborate in creating a vision for water sensitive Bendigo in 50 years’ time and begin to specify the steps needed to achieve this vision [

19]. The study used an action research methodology [

14,

20] where stakeholders contribute to knowledge co-production with the research team through a series of workshops, supported by pre- and post-workshop interviews, supplementary engagement and analysis activities. Bendigo was a major case study within a larger project as part of the Cooperative Research Centre for Water Sensitive Cities [

21]. A full presentation of the Bendigo project methodology can be found in the case report and Vision and Transition Strategy [

18]. The study received ethical approval from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval no CF15/760-20150003451).

2.1. Study Context

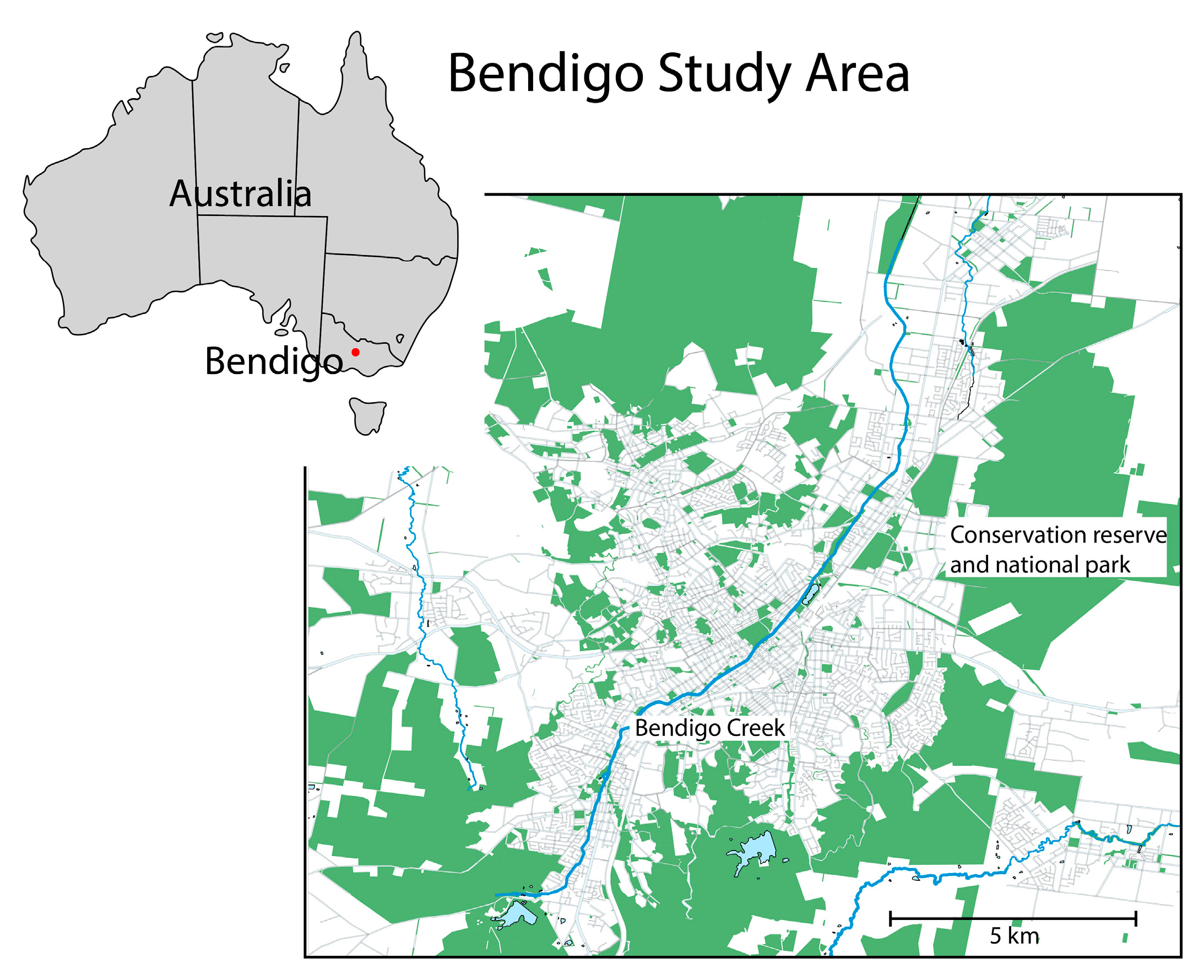

Bendigo is a regional town in Victoria, Australia with a population of just under 100,000 people. The town is located in central Victoria approximately 150 km from Melbourne, the state capital, see

Figure 2. The town was originally established around gold mining activity in the area and is located on either side of the Bendigo Creek. The town has a long history of water challenges. The millennium drought which ran from 1996–2010 in Eastern Australia had a devastating impact on Bendigo and resulted in extreme domestic water restrictions for citizens and significant changes in water planning [

22]. As a result, there is a strong interest by both water professionals and community members in managing water effectively in the future. In recent years, the town has also experienced flash flooding from the creek and there are problems with groundwater pollution from previous gold mining in the area. In contrast to other parts of the world, such as Africa, Australia does not have a system of water user associations that have a formal role in collecting water fees, maintaining infrastructure or distributing water [

23]. Instead, Australia has a complex, hybrid model of natural resources and water management where community participation sits alongside neoliberal governance processes [

24]. Australia has a three-tier government structure—national, state and local government, and responsibility for water management rests primarily with the middle tier.

For Bendigo, the State Minister for water has responsibility for water management and distribution through several government departments including the Department of Land, Water and Planning, the catchment management authority and Coliban Water, the state-owned water corporation [

25]. Yet the local government, the City of Bendigo, also influences water management through their role as a planning authority [

25].

For this study, a steering committee was established at the beginning of the research project to guide the Bendigo activities and ensure the local context fundamentally informed the project design and stakeholder engagement. Participants were primarily from local organisations and there were also representatives from the water corporation and representatives from the Department of Land, Water and Planning. The steering committee helped to ensure the project would have a local impact through alignment with current and upcoming opportunities, effective strategic positioning and targeted communications with key agencies that would facilitate broader endorsement and support of the project activities and outcomes.

2.2. Recruitment of Participants

Community participants were recruited into the Community Champion Group by self-selection based on their interest in the topic. A variety of approaches to publicise the project were used, including social media campaigns, regional newspaper advertising, council newsletters and direct correspondence to community groups in the conservation and sustainability domain. Recruitment was supported by a project website for communication and registration. The website also featured an interactive map application to collect ideas about improving Bendigo’s built and natural environment. The map aimed to stimulate initial critical thinking about the current urban water system in Bendigo and generate a “first pass” at system solutions. There were approximately 20 posts of water management ideas on the map and this information was used to supplement workshop discussion.

There were 31 participants in the Community Champion Group. Brief surveys prior to the workshops assessed demographics, motivation for participation, and trust in different organisations to act in the public interest and implement water management plans. Half of the group were female. Just over two-thirds of participants were aged between 36 and 64 years of age (the most common age range was 46–64, which comprised about 43% of participants). Most participants had a tertiary qualification (79%). About half of the participants in the Community Group had an interest in participating due to paid or volunteer work in the water sector or natural resource management. Several other participants appeared motivated by particular water management issues, including Bendigo Creek, groundwater management, or management of water bodies for recreational use. The remainder of the participants reported a general interest in sustainability, the natural environment, or the future of Bendigo.

Three additional focus groups were conducted, targeting groups not well-represented in the main community workshop series. These groups were selected as comparisons to the ‘community champions’ on the basis of previous research which found that young people and people from low socio-economic status backgrounds who were renting were less engaged with water issues and conversely, homeowners with gardens were more engaged with water issues than the general population [

15]. We recruited one group of low-income renters (earning under

$50,000 AUD per year), one group of young people aged 18–35, and a group of homeowners who were active gardeners to participate in focus groups. Each focus group included ten individuals who were randomly selected by a recruitment agency and paid an honorarium to participate.

In parallel to the Community Champion Group, an Industry Group workshop series involving representatives from the water, planning, development and environment sectors was established. These participants were personally invited based on the advice of the local steering committee to ensure a rich mix of organisations, disciplines and perspectives, with an emphasis on people recognised as thought leaders, experts and visionaries who would be well-placed to become industry champions of Bendigo’s water sensitive city vision. Participants included representatives from State government, local government, the water utility, catchment management authority, consultants, private developers and a Traditional Owners organisation. The industry group included 47 participants, although individuals’ attendance varied from workshop to workshop.

2.3. Workshop and Focus Group Activities

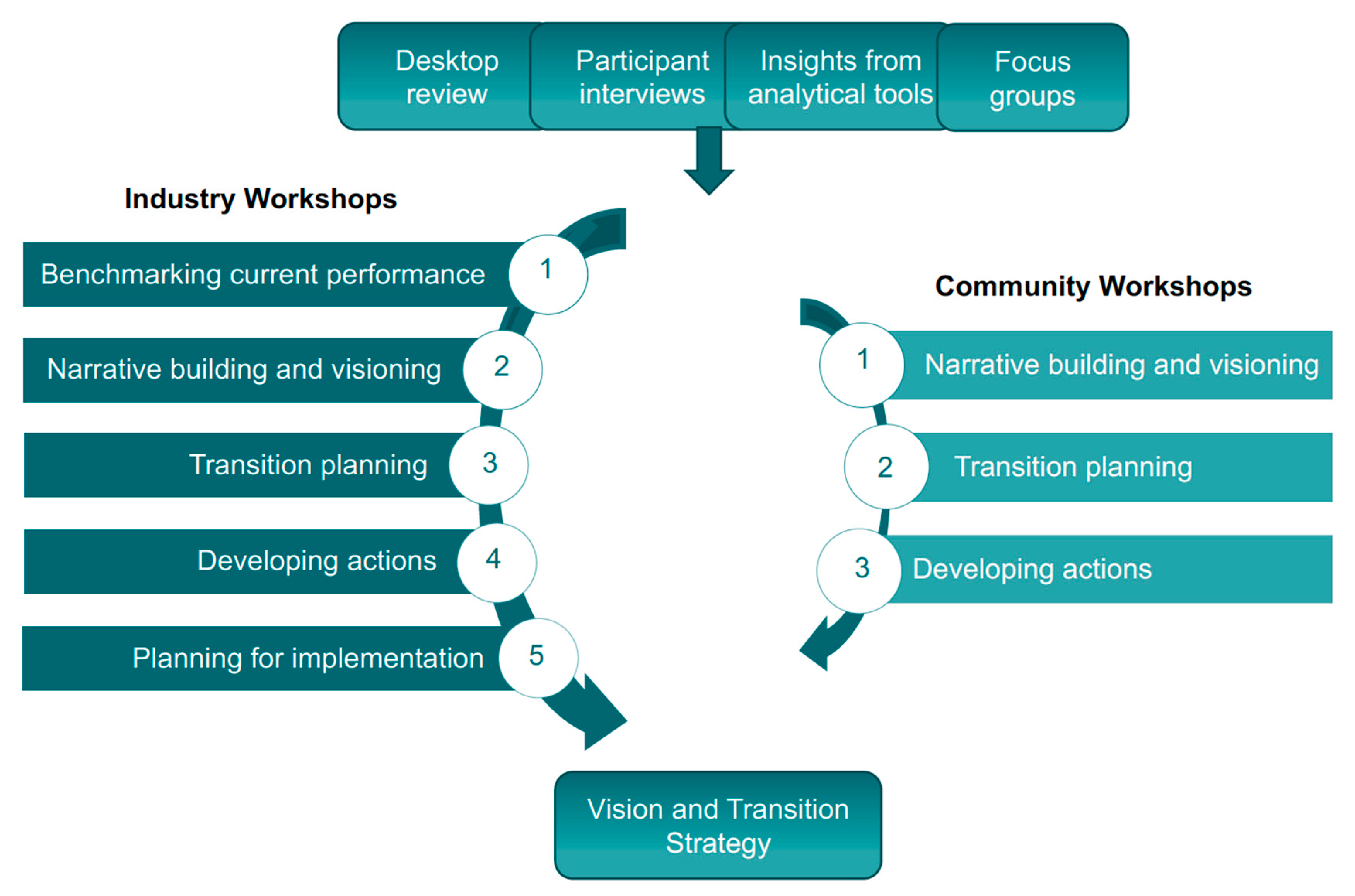

The workshops were designed to facilitate open and in-depth discussion among participants. The engagement process was conducted over an 8-month period between September 2017 and April 2018. As shown in

Figure 3, the engagement process involved desktop review by the project team, individual interviews with workshop participants, a series of five one-day workshops for industry participants, a series of three three-hour workshops for self-selected community participants, and three two-hour focus groups with segments of the community that were underrepresented in the core workshop series. Iterative synthesis and analysis by the research team across these sources of data produced key elements of Bendigo’s vision and transition strategy. The content developed and the insights gained from the parallel Community and Industry processes were reported to both groups and built upon iteratively [

8]. In addition, a pre-workshop survey and post-survey workshop survey was conducted to evaluate the engagement process.

There was a small degree of overlap between the Community and Industry Workshops; some industry participants attended the community workshops to support cross-fertilisation of ideas between the two groups. This was made transparent to the participants during each workshop. Two participants recruited through the community process attended the last industry workshop.

The three additional focus groups each ran for 2 h and covered five topics. For consistency of the process, the activities for each discussion topic were based on those undertaken by participants in the main Community Workshop sessions: (1) What they love about Bendigo; (2) their knowledge of water sensitive city concepts; (3) their vision for Bendigo’s water future in 50 years’ time; (4) their reflections on the draft vision for Bendigo’s water future generated through the main workshop series; (5) how they would like to be involved in guiding Bendigo’s water future. Insights from the focus groups were presented to the main Industry and Community workshop participants during relevant discussions to provide opportunities for the perspectives of this broader community sample to inform their thinking and creation of vision and transition strategy content.

The broad limitation of our research is that it is based on one in-depth case study that is highly context-dependent. A further limitation of our research was that although the Traditional Owners of the land, the Dja Dja Wurrung, were represented in the Industry Group, a dedicated process to gather further input from indigenous community members would have been valuable if time and resources had allowed. As illustrated by the Vision, see

Figure 1, both the community and industry participants recognised the important role and potential of the Dja Dja Wurrung to be community champions and contribute to community-led stewardship and long-term water planning.

3. Results

Community members made a valuable contribution to the long-term vision for a water sensitive Bendigo. The final integrated version is illustrated in

Figure 1.

3.1. Local Action and a Local Focus Was Perceived to be Important

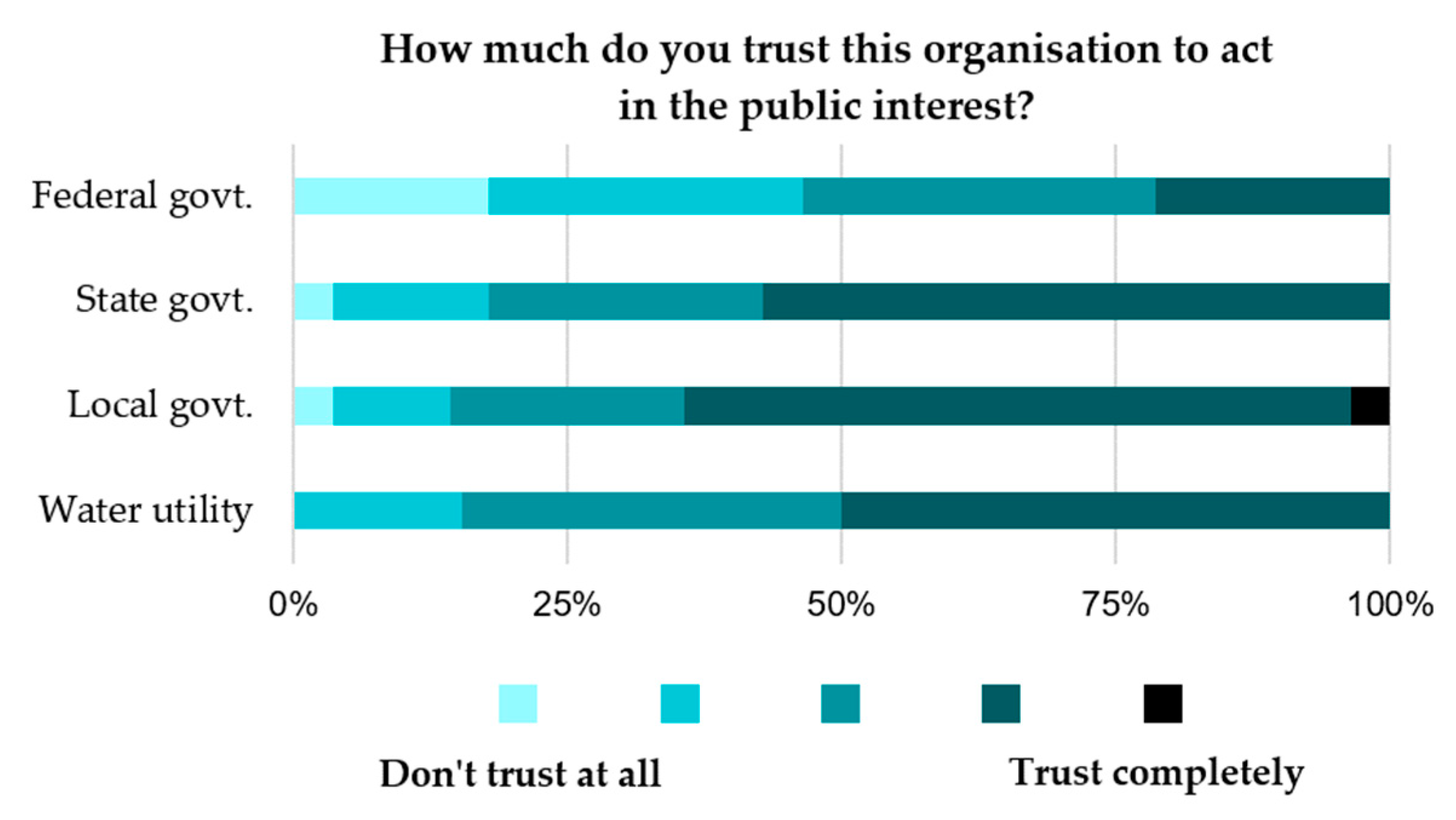

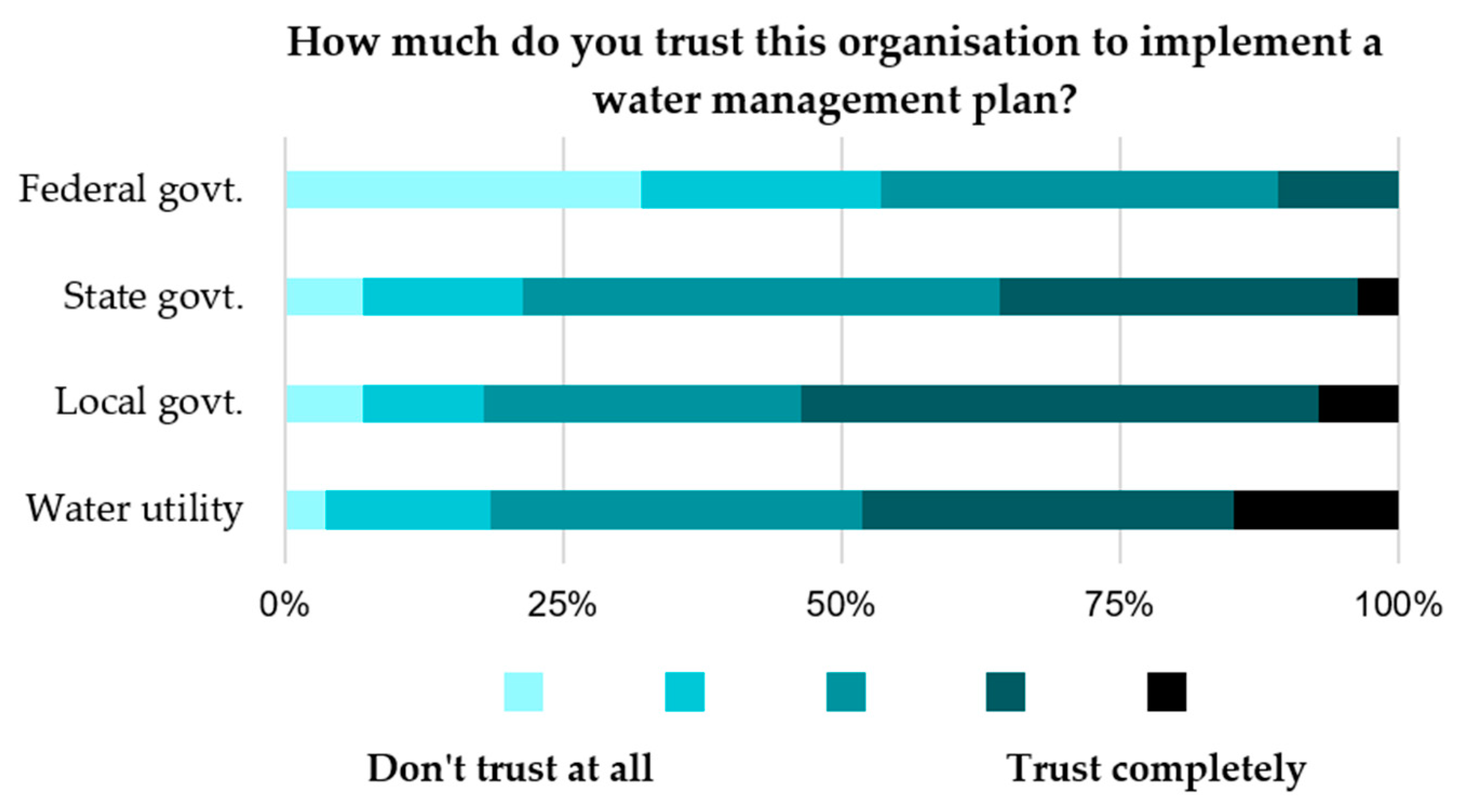

Pre-workshop survey results indicate that for the community champion cohort, trust in the local council and local water utility was significantly higher than that of the federal government. While nearly two-thirds of respondents trust local government to act in the public interest, less than a quarter felt the same way about the federal government, see

Figure 4. These differences were more extreme when it came to implementing a water management plan effectively, see

Figure 5. This disparity in local and federal trust suggests that transitions focused on local action, at the city scale, may be more effective at building community participation than ones focused on a state or national agenda.

The Bendigo case study aimed to explore community values and aspirations through their connection to place. The ‘Why I love Bendigo’ group activity undertaken with all participants served both as an ‘ice-breaker’ and to ground participant thinking in the present values of the place before considering their aspirations for the future in the visioning activity. In the activity, participants were asked what they loved about their city and wanted to be preserved in the face of challenging future contexts of climate change and population growth. A common sentiment was that Bendigo is an ideal size; it is small enough to support a cohesive, friendly community, but large enough to have city-scale services and cultural facilities. Bendigo’s unique identity, history and culture, demonstrated by the grandeur of some of its architecture and the presence of Indigenous Dja Dja Wurrung heritage and Chinese heritage, give people a sense of pride in their city.

Bendigo’s urban environment is also an important attraction. Participants reported that Bendigo does not have the congestion and poor air quality of larger cities, and it has relatively accessible and well-preserved suburbs. With very few multistorey buildings, it is possible to see across the town and into open space. Participants noted the way that Bendigo Creek linked many neighbourhoods with its linear path through the city and participants could see its potential for improvement through naturalisation. The Box-Ironbark woodlands that surround the urban area are also considered a special feature of the city’s geography. Participants also noted that the climate was attractive.

There was a high level of agreement across industry champions, community champions and focus group participants about the best features of Bendigo. A strong connection to place was evident in each of the group discussions.

The Community Champion Group generated ideas that elaborated on the themes of the vision (

Figure 1) and pointed to potential practices or biophysical changes in their town that would realise the vision. These ideas ranged in scale from community gardens in key locations, to city-wide suggestions such as using Bendigo’s ephemeral creek system as a vehicle for engagement with the potential to connect people and cultures. Systemic solutions included recycling wastewater for potable use and making better use of rainwater, stormwater and groundwater. The transition actions that participants identified as appealing included:

Introduce more opportunities to participate in planning and deliberative forms of governance,

Establish processes to improve the links between industry and education institutions,

Raise community awareness of water dependence (e.g., embodied water consumption labelling, installing smart meters),

Promote indigenous water values (e.g., recruiting a Traditional Owner ambassador for the city of Bendigo), and

Create organizational and institutional cultures that are supportive of innovative funding or service delivery models and more accepting of experimentation.

The community champions also suggested strategies for connecting and engaging the broader community to the vision of a water sensitive Bendigo:

Identify and articulate why a water sensitive Bendigo is important for the community and how community members can benefit from water sensitive solutions.

Employ a targeted approach for effectively engaging with specific community sectors, by identifying a ‘hook’ for each segment and developing associated messaging.

Understand the barriers (e.g., time, money, family commitments, language, level of knowledge) and needs (e.g., social interaction, financial incentive, opportunity to contribute) for different community segments in relation to engagement and develop tailored engagement approaches (e.g., surveys, workshops, planning meetings, working bees, and testing or trialling products).

Be focused, authentic and transparent about the purpose of engagement and the desired result (e.g., goals might include public pressure, votes, support, raising awareness through word-of-mouth or fund-raising), and show how people’s contributions have been considered.

3.2. Social Learning Occurred over Time

The community champion workshop series demonstrated how ideas generated by community members developed over time. In the first community workshop, the visioning process started with brainstorming activities that produced bold, creative and idealistic visions of Bendigo’s future. Over the next two workshops, participants had time to reflect and distil initial ideas into sophisticated and well-informed concepts. For example, in the initial exercise where participants explored the possible futures for Bendigo, the ideas of complete self-sufficiency in water, energy and food were prominent vision themes. One month later, at the second community workshop, a synthesised version of the water story and vision, which included input from the Industry group, was presented back to the participants. Through group discussions, the important role of enduring regional partnerships within Bendigo’s water story became apparent and participants reconsidered the viability of becoming completely ‘self-sufficient’. Through reflection and refinement participants distilled this idea into a vision of Bendigo becoming sustainable through enduring partnerships.

This important later step of reflection and refinement was not able to take place in a one-off engagement process such as the focus groups. We found that through providing an iterative process with time and a supportive and trusting environment, community members could think imaginatively, welcome different perspectives and consider new information to distil creative ‘blue-sky’ ideas into a sophisticated, well-informed and relevant vision. This suggests that allowing sufficient time for community members to engage, understand and deliberate is an important aspect of effective participatory planning processes.

The research team also learned about community engagement processes and developed their facilitation skills over the course of the research project. Four to six researchers attended each workshop and collaborated on developing and refining activities and recording methods. Two researchers facilitated the focus groups. Responsibility for running workshop sessions was spread between the team, with the project leader presenting the introductory and summary sessions. These sessions were important for emphasizing the value of community contributions as well as setting expectations about processes and outcomes. The team took a reflexive approach to the workshops, evaluating processes and modifying strategies after each workshop.

The separate workshop processes for the Community and Industry groups enabled participants with varying knowledge and experience to participate and contribute meaningfully; imparting their lived experience and local knowledge to create a vision that resonated with the wider Bendigo community. Social learning was a key driver for participating in the workshop series and a key outcome. In the pre-interview, the majority of participants indicated that they were interested in the topic of water management and the workshops would be an opportunity to increase their learning, knowledge and understanding. Evaluation survey results confirm that social learning was an important part of the process for many community participants: 82.35% of respondents agreed that their understanding of the key water issues for Bendigo had changed because of the workshop series. Participants expressed personal benefit from discovering new connections, new perspectives and new information. Many felt they had a greater understanding of the complexities of water management. One participant said they had an “increased level of knowledge” and appreciated the “thought-provoking visions and diversity of ideas”. Another reported it was “great to hear from others around their issues, great broad range of community and agency staff input, it challenged some personal thoughts and broadened my considerations. I appreciated the future thinking and it gave me an appreciation of community influence”. Other participants spoke about the personal benefits they gained from their community champion experience. For example, one participant stated they had a “greater understanding of all the different aspects of water outside of my sphere plus networking and discovering opportunities to progress my own related projects”. Another confirmed that the process had provided “networking opportunities and inspiration to take away and get cracking on some action”.

Bendigo community champions recognised that the diversity of perspectives represented in their community is an important asset when considering how to achieve change. They felt that community members can bring fresh approaches and energy to solving problems as they are unconstrained by expert knowledge of current solutions and common roadblocks.

3.3. Community Champion Views May Differ from Other Community Groups

The self-selected community champion participants had characteristics typical of highly engaged ‘water sensitive citizens’ [

15,

16]. They were a well-educated group who were generally knowledgeable about water and the environment and felt they had something to contribute to public discussions about water planning. By contrast, the focus group participants had more varied demographic backgrounds, less knowledge about water planning and, in some of the groups, less commitment to the environment. The focus groups provided an important opportunity for the team to test the water sensitive vision with representatives of the broader community. There were some important but subtle differences between views expressed in the focus groups and by the community champions, as summarized in

Table 1.

A further example of the contrast between community champions and the wider community is illustrated through discussion of Bendigo Creek. In the first community champion workshop, one of the participants stated that the Bendigo Creek was one of the things she loved about Bendigo. By contrast one of the women in the youth focus group expressed her disdain for the waterway: ‘The creek is little more than a drain, I’d never take anyone there’. The differences between the community champions and other groups were rarely this stark. However, the findings suggest that it is prudent for water planners to check that their plans and strategies resonate with diverse groups beyond community champions.

3.4. Community Champions Can Play a Valuable Knowledge Brokering Role

The Bendigo case study process presented an opportunity to mobilise a community network in the hope that it will lead to ongoing momentum and partnerships. The Community Champion Group were ideal candidates for this because they were already highly interested and engaged in water and broader sustainability issues. The last community workshop was primarily devoted to discussing the community’s role in generating change and the type of involvement the participants saw for themselves in shaping the next stage of Bendigo’s water sensitive transition.

The community’s role in driving change was vital according to the Community Champion Group. They recognised that current approaches to shaping cities need improvement and saw that collective ownership and leadership of Bendigo’s water sensitive city vision was critical for achieving change.

The community champions felt that members of the broader community would be interested in being involved in and contributing to the transition to Bendigo’s water sensitive future. However, they recognised that different people will have different motivations, constraints and opportunities that will influence their receptivity to different forms of engagement. We reported the focus group results back to the community champions in the last workshop and asked for their suggestions for improving engagement with diverse groups to drive the transition of their water sensitive future. As shown in

Table 2, the community champions made insightful suggestions.

These ideas resonated strongly with the focus group data from young people and low-income groups. However, the community champions, perhaps with the benefit of considering community engagement over several months rather than a one-off focus group, took a broader perspective and suggested additional strategies not mentioned in the focus groups. In the focus groups, participants suggested that they would be willing to be involved in future planning through answering surveys or attending a focus group, participating in working bees or trialling products. Some of the participants in the youth and low-income focus groups said that they did not have enough knowledge to contribute further while others said that time and family commitments could prevent them from participating. This is congruent with other research that has found socio-economic differences in engagement [

15].

3.5. Community Members as Effective Contributors to Long Term Planning

Importantly, the Industry Group valued the opportunity for a dedicated process involving community members to contribute to Bendigo’s water sensitive vision and transition strategy, and found the insights generated in both the community champion workshops and the supplementary focus groups to be useful and important. The professionals in the industry group were interested to learn about community perspectives and respected their contributions.

The resulting 50-year vision of water sensitive Bendigo, see

Figure 1, benefited from input from the community in two key ways. Firstly, the vision prioritized the health and well-being of the community alongside environmental sustainability and technical solutions. Secondly, the vision was distilled and refined over the course of the workshops in plain non-technical language. Input from the community champions on appropriate wording was particularly useful [

26]. In terms of future governance and planning processes, the Industry Group stressed that it was important that community representatives are part of the ongoing champion network that is currently being established in Bendigo to guide water planning and transition actions to achieve the vision of water sensitive Bendigo. The Industry Group recognised the role they have as professionals to make space for community voices in planning and decision-making and the need for robust and deep community engagement in water planning going forward.

These results demonstrate that community champions with their deep understanding of both community and environmental issues can act as a useful bridge between industry professionals and the wider community and suggest innovative solutions for community engagement and action.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Our research builds on knowledge about stakeholder engagement and participatory processes in water management which has demonstrated the importance of high quality, careful engagement that is flexible, iterative and sensitive to context [

8,

9,

17]. The Bendigo case study offers insights into the role that community champions can play in long-term water planning. Community champions are likely to be self-selected which has both advantages and drawbacks. On the positive side, it is well recognised in transitions research that passionate champions who have the opportunity to strengthen relationships and establish a collective commitment to action are critical drivers of transitional change [

27]. Seeking out and working with community champions alongside professionals through an iterative process provides an opportunity to mobilise engaged and motivated local networks [

8]. As Dillion and colleagues found with their research, community action groups can play a crucial role in assisting water planning when community concerns are heard, acknowledged and acted upon [

13]. Our findings also suggest that community champions could be critical for establishing ongoing momentum and effective partnerships in long-term water planning.

Yet, our findings also chime with research on civic participation and deliberative democracy that participants who self-select into these processes are likely to be relatively homogenous and privileged i.e., college educated, middle class and white [

28]. In our research, the community champions were highly educated and highly engaged in environmental issues compared to other community members [

15]. As the focus group results demonstrated, the broader community may not bring the same perspectives or level of commitment as community champions to sustainable water planning. As a solution to the ‘conundrum of participation’ this is the challenge of achieving representative samples in participatory processes [

28], we propose that additional shorter engagement activities can be a useful strategy to supplement the perspectives of community champions and bring diverse viewpoints into the conversation. We found that purposefully engaging with community members who are less likely to be represented in participatory forums provided a valuable opportunity to check plans and city visions and seek ideas and feedback from diverse groups as part of long-term water planning. Shorter engagement techniques such as focus groups can be a useful tool to provide this feedback, allowing agencies to calibrate their planning frameworks to align with broader community aspirations.

The community champions in our research were participative citizens [

28] who were keen to have a greater role in water planning and policy-making in the long term. This was demonstrated by the collaborative vision developed for Bendigo that there would be ‘consistent and inclusive governance that supports an empowered community and integrated, adaptive approaches to water planning and management’, see

Figure 1. The higher levels of trust shown for local government and local organisations rather than State government also suggests that community champions would welcome a role in formal governance arrangements at the local level. However, realizing the aspiration for citizens to have a formal role in policy making is challenging in the current Australian context of complex water governance arrangements and shifting policy reform cycles [

24,

29].

Our research confirms that involving community champions in long-term water planning processes was extremely valuable. Community champions can offer insightful suggestions on what a water-sensitive city would look like in their local context. They can challenge the potential ‘group think’ of water professionals who may have preconceived ideas of problems and solutions, questioning their assumptions and jargon. They can also set clear expectations for agencies to cooperate to deliver integrated community outcomes towards a water sensitive future. After participating in an iterative planning process like the case study discussed in this paper, community champions enjoy the social learning aspects of collaborative workshops and become valuable ‘lay experts’ and knowledge brokers who can bridge the gap between water professionals and the wider communities they serve. Further research is needed to confirm the applicability of our findings in other local contexts around the world but, on the basis of the study presented here, the benefits of involving community champions in collaborative water planning is worth the investment in such processes.