Abstract

Based on the Köppen Geiger (KG) classification system, this review article examines existing studies and projects that have endeavoured to address local outdoor thermal comfort thresholds through Public Space Design (PSD). The review is divided into two sequential stages, whereby (1) overall existing approaches to pedestrian thermal comfort thresholds are reviewed within both quantitative and qualitative spectrums; and (2) the different techniques and measures are reviewed and framed into four Measure Review Frameworks (MRFs), in which each type of PSD measure is presented alongside its respective local scale urban specificities/conditions and their resulting thermal attenuation outcomes. The result of this review article is the assessment of how current practices of PSD within three specific subcategories of the KG ‘Temperate’ group have addressed microclimatic aggravations such as elevated urban temperatures and Urban Heat Island (UHI) effects. Based upon a bottom-up approach, the interdisciplinary practice of PSD is hence approached as a means to address existing and future thermal risk factors within the urban public realm in an era of potential climate change.

1. Introduction

Given the increase of population living within cities, and extreme conditions and aggravations as a result of climate change projections, there has been a resultant response from the international scientific community. When approaching high urban temperatures at micro/local scales, it has so far been argued that “most cities are not designed to ameliorate these effects although it is well-known that this is possible, especially through evidence-based climate-responsive design of urban open spaces” [1] (p. 1). As a result, the bottom-up role of local urban spaces in accommodating urban liveability and vitality is continually receiving attention within the international community [2,3].

So far, top-down climatic assessments and thermal comfort studies have often resorted to more simplistic analysis tools. As an example of this incongruity, it has been identified that global entities such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change “describe the effect of weather and climate on humans with a simple index based on a combination of air temperature and relative humidity. The exclusion of important meteorological (wind speed and radiation fluxes) and thermo-physiological variables seriously diminishes the significance of [presented] results.” [4] (p. 162). Consequently, it can be argued that such discrepancies can hinder fairly ‘evident’ and important microclimatic considerations for a multitude of professionals at local scales, such as architects and urban planners/designers. For example, Katzschner [5] identified that irrespective of local ambient temperatures (Tamb), there was an acute disparity of thermo-physiological stress between areas exposed to the sun from those cast in the shade. The influences of such disparities were also confirmed by observed pedestrian behavioural patterns within outdoor spaces by Whyte [6] who suggested that “by asking the right questions in sun and wind studies, by experimentation, we can find better ways to board the sun, to double its light, or to obscure it, or to cut down breezes in winter and induce them in the summer.” [6] (p. 45). Similar perspectives were also established in other early studies (e.g., [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]).

Consequently, and embracing the significance of future horizons that shall likely witness ensuing aggravations of the climate system, principals such as the urban energy balance (Equation (1)) as presented by Oke [16] are particularly relevant when facing such challenges.

whereby: Q* → net of all-wave radiation, QF → anthropogenic heat flux, QH → is the flux of sensible heat, QE → the flux of latent heat, ΔQS → heat stored within the urban fabric, and ΔQA → net heat advection.

Due to delicate equilibrium of the urban climate, existing variables such as UHI intensities and Tamb values should be approached as ‘base values’ that could be further offset by future modifications of the urban energy balance. As a result, existing studies have already identified the need to consider how (i) the projected increase in frequency, intensity, and consecutiveness of annual hot periods can impact Q* (i.e., altering the incoming/outgoing balance between short wave and long wave radiation) (e.g., [4,17]); (ii) in addition to other anthropogenic emissions, the expected increase in need for urban cooling (e.g., air conditioning) can escalate QF (e.g., [18]); (iii) the heat storage (i.e., ΔQs) of surface materials can increase as a result of radiation variations (e.g., [19]); and, lastly, (iv) potential reductions in variables such as wind patterns (as a result of additional urbanisation) can lead to undesired urban reductions of ΔQA [20].

Adjacently, and in accordance with the ‘climate-comfort’ rational of [7], this review study focuses on merging the potentiality of bottom-up perspectives with those of local urban outdoor spaces. The term of ‘locality’ is utilised in this study to describe a scale on which public space measures can render relevant, yet direct, thermal modifications on pedestrian comfort thresholds, which can vary from those of an urban canyon to those of an urban park; regardless, and throughout the article, such types of settings are always identified. Taking this line of reasoning a little further in the context of local decision making and design, this raises two predominant concerns: (i) the requirement to improve and/or facilitate the design guidelines within such environmental perspectives for local action and adaptation; and (ii) given the growth of the climate change adaptation agenda, the growing cogency/necessity for local, thermal, climate-sensitive action. For these reasons, the breadth between theory and practice needs to continue to be developed to inform the better design and maintenance of Public Space Design (PSD) in an era that is vulnerable to potential climate change [17,21,22,23].

In addition, it can also be argued that the role of PSD with respect to the application of design/assessment guidelines can potentially, in the future, be partly associated with a top-down approach. More specifically, once consolidated, regulatory entities can issue generalist bioclimatic ‘best practice’ recommendations to address human thermal comfort thresholds in different urban circumstances and scenarios. Nevertheless, it is suggested by this review article that (i) the state-of-the-art in this field is not yet mature for such a generalist approach, particularly considering the delicate relationship with local settings and the intrinsically associated influences of microclimatic stimuli; and (ii) whilst the breadth between theory and practice must be reduced, such a reduction at this stage should be matured between urban climatology and urban planning/design at local scales before being transposed to such prospective top-down regimental approaches.

With the objective of discussing and organising the application of scientific knowledge when addressing thermal comfort thresholds through PSD, this article presents two sequential reviews of the state-of-the-art. Firstly, general existing approaches to pedestrian thermal comfort thresholds are described both at a quantitative level (i.e., the identification of thermo-physiological indices) and at a qualitative level (i.e., the identification of psychological thermal adaptation dynamics). Secondly, four Measure Review Frameworks (MRFs) are constructed that describe the actual application of different types of PSD measures within three subtypes of ‘Temperate’ climates according to the Köppen Geiger (KG) classification system.

2. Methods & Review Structure

2.1. Application of Köppen Geiger Classification System

Within this article, the KG classification system is utilised to determine the climatic context of thermal PSD projects within the international arena. Such an approach enables the organising of respective projects into different climatic contexts based on local micro/climatic characteristics.

As suggested by Chen and Chen [24], the KG climate classification (i) provides a more encompassing description of climatic conditions/variations and (ii) has been increasingly used by the international scientific community. The classification represents an empirical system and serves as a record by which to determine the climate for any particular region over thirty years as defined by the World Meteorological Organisation. The principal climatic variables considered are Tamb and precipitation, which are subsequently computed every decade to smooth out year-to-year variations. Consequently, the system is extensively used by researchers and scientists across a large range of disciplines as a method for the climatic regionalisation of climatic variables from top-down climatic assessments (e.g., [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]).

As identified in numerous studies (e.g., [36,37,38,39,40]), the scientific community has recognised a weakness in studies that focus on Mediterranean ‘Csa’ climates with regard to local approaches to thermal comfort thresholds. Such a deficiency often generally relays to a lack of local scale design guidelines and precedents that could otherwise inform practices such as PSD to attenuate thermal comfort during dry and hot Mediterranean summers. Additionally, and commonly within regions such as southern Europe, many cities often present lapse of meteorological and climatological data that would prove useful in informing design and decision making within the public realm; in these regions, such gaps of knowledge are particularly evident within municipal Masterplans, as exemplified by cases such as Portugal and Greece.

Based on the most recent version of the KG system by Peel, Finlayson, et al. [27], an emphasis was made upon ‘Temperate’ climates, with the reviewed PSD measures pertaining to three specific subgroups within the ‘C’ group as presented in Table 1. Although the focus was attributed to ‘Csa’ climates, it was found that the other ‘Temperate’ climatic zones also presented valid case studies and projects. In the case of ‘Cfb’, although summer temperatures are generally lower (and rarely surpass 22 °C during the summer), numerous studies still revealed that pedestrian comfort thresholds could be improved through numerous PSD interventions. With regard to ‘Cfa’, which presents the same type of summer temperatures as ‘Csa’, such studies also had to manage the additional aspect of considering high RH levels during the summer to cool Tamb levels, which was particularly relevant within the last MRF presented in this review study.

Table 1.

Description and criteria for the three subgroups within the Köppen Geiger ‘Temperate’ (C) group| Source: (Adapted from [27]).

2.2. Measure Review Framework Construction

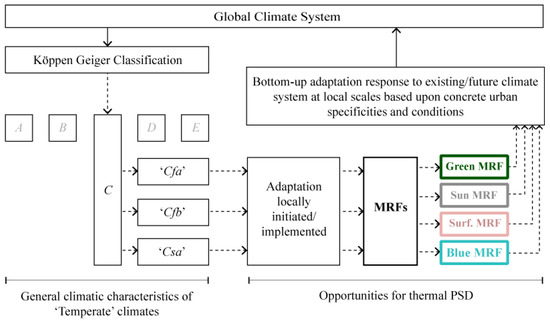

Established on the argument that adaptation is not a ‘vague concept’ [41,42,43,44], and that beyond top-down information, it also must be established on local scale observation and understanding [4,45], Figure 1 represents how the MRFs were approached as a means to organise different existing approaches to local thermal sensitive PSD. As adaptation invariably takes place ‘locally’, the MRFs were thus perceived as a means to review existing approaches through PSD measures to tackle similar climatic constraints and threats.

Figure 1.

Identification of Measure Review Frameworks (MRFs) within bottom-up approaches to local thermal sensitive PSD within selected ‘Temperate’ climates.

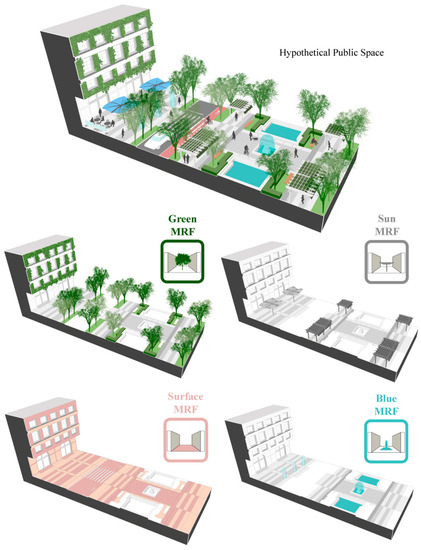

In an effort to evaluate current available approaches to thermal comfort thresholds through PSD, this review article organises existing studies into four predominant sections. Within each section, specific types of PSD measures were organised into a respective MRF, with concrete details regarding their specificities, and resulting thermal outcomes. As represented in Figure 2, four MRFs were constructed that assessed projects that utilised different types of PSD measures, these being: (1) Green MRF—urban vegetation; (2) Sun MRF—shelter canopies; (3) Surface MRF—materials; and, (4) Blue MRF—water/misting systems. Such a division of measures was based on the similar distinctions discussed in [46,47,48]. Furthermore, as there are likely to be projects that have not been properly documented or published thus far within the scientific community, the aim of each MRF was to establish a representative selection of projects/studies within the specified ‘Temperate’ subgroups.

Figure 2.

Representational division of thermal attenuation measures from a hypothetical public space.

3. Examining Thermal Indices and Adaptation Dynamics

Within the existing literature, it is a well-established fact that human thermal comfort is strongly correlated to outdoor urban environment [15,36,39,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59]. In order to assess the effects of the thermal environment on humans, it has been argued that the most efficient means to undertake this evaluation is through the use of thermal indices that are centred on the energy balance of the human body [60]. So far, within the international community various indices have been developed and disseminated, including the (i) Standard Effective Temperature (SET*) [61]; (ii) Outdoor Standard Effective Temperature (OUT_SET*) [59,62]; (iii) Perceived Temperature (PT) [63]; (iv) Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) [64,65]; (v) Index of Thermal Stress (ITS) [8]; (vi) Predicted Percentage of Dissatisfied (PPD) [64]; (vii) COMFA outdoor thermal comfort model [66]; (viii) Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI) [67,68]; (ix) Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) [69,70]; and (x) Predicted Heat Strain (PHS) [71].

It should be noted, however, that of these mentioned indices, many are designed for indoor use only, such as SET, PMV, and PPD. The justification for this is that the type of microclimatic stimuli is very different to those found outdoors where non-temperature variables must also be accounted for. As a result, indices that initially focused upon indoor conditions need to be ‘modified’ in order to accurately assess outdoor conditions, as exemplified by the creation of the OUT_SET* from the original SET index. In the case of PMV and PPD, and within the scope of approaching thermal comfort and indoor air quality, it is worth emphasising the significant contributions of Fanger [64] and, to some extent, the complementary aid of Gagge [72] with regards to specific thermal issues such as human perspiration and clothing vapour diffusion resistance. To date, the comfort equation of Fanger [64] is still widely used within the scientific community, and the PMV index continues to be the basis of several national and international standards.

Adjoining outdoor indices is the Physiologically Equivalent Temperature (PET) [15], which has been one of the most widely used steady-state model in bioclimatic studies [73]. Based on the Munich Energy-balance Model for Individuals (MEMI) [10], it has been defined as the air temperature at which, in a typical indoor setting, the human energy budget is maintained by the skin temperature, core temperature, and perspiration rate, which are equivalent to those under the conditions to be assessed [74]. In addition, the default setting considers a clothing insulation of 0.9 and a metabolic rate of 80 Watts, yet such values can also be regulated. The justification for a greater use of this index can likely be attributable to (i) its feasibility in being calibrated on easily obtainable microclimatic elements, and (ii) its base measuring unit being (°C), which simplifies its comprehension by professionals such as urban planners/designers and architects when approaching climatological facets.

Recently, there have been numerous studies that have made adjustments to the PET index based on (i) determining additional variables, and (ii) refining the integrated thermoregulation model. Within the study conducted by Charalampopoulos, Tsiros, et al. [56], and recognising the fact that exposure to thermal stimuli is not typically momentary, cumulative aspects were integrated within the PET index. More specifically, and referring to their methodology, and amongst others, the PET Load (PETL) and the cumulative PETL (cPETL) were outlined, whereby (i) PETL refers to the outcome difference from optimum condition, hence permitting a specific value that denotes the amount of physiological strain on optimum thermal conditions, and (ii) cPETL ascertains the cumulative sum of PETL during a designated number of hours.

Oriented specifically towards improving the calibration of the thermoregulation and clothing models used within the PET index, Chen and Matzarakis [75] launched the new modified PET (mPET) index. As described in their study, the main modifications of mPET are the integrated thermoregulation model (modified from a single double-node body model to a multiple-segment model) and the updated clothing model, which relays to a more accurate analysis of the human bio-heat transfer mechanism. By referring to the ranges of Physiological Stress (PS) on human beings as described by Matzarakis, Mayer, et al. [76] (Table 2), it was identified that (i) unlike the mPET estimations, PET had the tendency to overestimate PS levels during periods of higher thermal stimuli, and (i) the likelihood of comfortable thermal conditions was higher through the application of the mPET index. Based on the bioclimatic conditions of Freiburg, the results from the study were also subsequently verified for the case of Lisbon by Nouri, Costa, et al. [36] and Nouri, Fröhlich, et al. [77]. Furthermore, and considering the calibration of the stipulated ranges of PS, variations of thermal indices and their associated calibration against stress levels have also been items of revision within various studies in the last decade (e.g., [51,56,78,79,80].

Table 2.

Ranges of the Physiologically Equivalent Temperature (PET) for different grades of Thermal Perception (TP) and Physiological Stress (PS) on human beings; internal heat production: 80 Watts, heat transfer resistance of the clothing: 0.9 clo (according to [58])|Source: (Adapted from, [76]).

Associated with the maturing know-how between human thermal comfort and that of urban climatic conditions, the continual extension and modifications of existing thermal indices shall very likely continue to grow. Such a phenomenon can be attributable to two predominant reasons: (i) the discovery of new developed methods to estimate thermal conditions, and (ii) the presence of new interrogations inaugurated by members of the scientific community. Adjoining the thermal indices already mentioned, and similarly to Fanger’s model [64], Salata, Golasi, et al. [81] proposed a logistic relationship between the observed percentages of dissatisfied and the mean thermal sensation votes on the ASHRAE 7-point scale in Mediterranean climates.

Given the growing amount of research into the application of thermal assessment methods, there has likewise been a parallel attentiveness to the intrinsic correlations between the different indices themselves (e.g., [73,82,83,84]). Additional indices were also discussed, particularly in Pantavou, Santamouris, et al. [73], which presented an extensive comparative chart of existing indices, their respective formulae, and correlation coefficients.

In addition, psychological (i.e., qualitative) aspects have also been discussed in parallel to thermal index (i.e., quantitative) attributes and are presented within Table 3. Within the studies, and in different ways, it was identified that ‘intangible’ attributes can also present an important factor when evaluating thermal comfort thresholds. Although more associated with indoor climatic conditions, such attributes have also been assessed by numerous recent accomplished studies as well [85,86,87].

Table 3.

Selected studies that assessed the relationship between thermal indices and qualitative attributes.

In line with the presented outcomes, when considering PSD approaches, the deceptively elementary vision of “What attracts people most, it would appear, is other people” [6] (p. 19) is still, today, of key significance. The described attraction here can be approached as an ‘adaptive thermal comfort process’ that pedestrians undergo when exposing themselves to a given outdoor environment. Within the study conducted by Nikolopoulou, Baker, et al. [93], such a process was broken down into three key categories: physical, physiological, and psychological.

Furthermore, within a subsequent study by Nikolopoulou and Steemers [94] six intangible characteristics were identified and correlated to pedestrian psychology within outdoor environments, namely: naturalness, expectations, past experience, time of exposure, and environmental stimulation. As to be expected, since these qualitative attributes enter the ‘intangible’ sphere, the quantification of each parameter is complex. In order to translate these factors into PSD terms and by correlating the six characteristics with the three sets of potential preferences of thermal environments as described by Erell, Pearlmutter, et al. [48], Nouri and Costa [95] discussed an adaptation of the existing ‘Place Diagram’ by the Project for Public Spaces (PPS). Based on its universal ‘What makes a great place’ diagram [96], the category of ‘Comfort’ was expanded to describe how design can be approached in a three step approach in order to (i) address microclimatic constraints, (ii) present physical responses, and, lastly, (iii) recognise how such interventions could potentially influence pedestrian psychological attributes.

Critical Outlook

Grounded on existing studies pertaining to both physiological and psychological aspects of approaching outdoor thermal comfort thresholds, it is possible to verify both (i) the steady growth of knowledge associated to the influences of the urban climate upon humans, especially at local/micro scales, and (ii) the potential for further studies to take such promising breakthroughs even further, which shall likely continue to be instigated by the international community given the potential unravelling of future climate aggravations. More specifically, and constructed on the discussion within this section, this review article suggests that there is an opportunity to do the following.

Firstly, further develop means to explore how qualitative attributes (e.g., expectations and past experience) can be better integrated within quantitative indices, even as an indicative ‘approach’. As a result, this effort could potentially present means to better predict (and account for) pedestrians willingly exposing themselves to thermal stimuli which would, in quantitative terms, imply surpassing their thermo-physiological comfort threshold. Such an approach would also present means for better approaching intricate elements such as ‘thermal adaptation and personification’ and using pedestrian behaviour simulation possibilities (e.g., agents).

Secondly, approach the necessity for the standardisation of a thermal comfort index for specific regions (such as MOCI) which caution. For although a standardised index could assist the establishment of a ‘common language’ between scientists, another perspective can be presented. More specifically, it can be argued that numerous existing thermal indices have already been identified as ‘common language’ within bioclimatic studies and, moreover, use the common unit of °C. As a result, a more ‘interdisciplinary standardisation’ should be reinforced, whereby the common language of one discipline (i.e., climatology/biometeorology) could be transposed on the sphere of urban design/planning through the continual dissemination of interdisciplinary studies and scientific collaboration.

4. Green Measure Review Framework

To date, numerous review articles have already discussed the capacity of urban vegetation (namely urban trees and ‘green’ areas) to attenuate urban temperatures and combat UHI effects, such as are summarised in Table 4. In addition to these review articles, other reviews of the state-of-the-art with a slightly different perspective have also been disseminated, namely the (i) specific thermal effects of reflective and green roofs [97,98], (ii) urban air quality and particle dispersion through the presence of vegetation [99] (research article), [100] (research article), and (iii) benefits and challenges of growing urban vegetation within the public realm [101].

Table 4.

Existing review studies of urban vegetation benefits and their general conclusions.

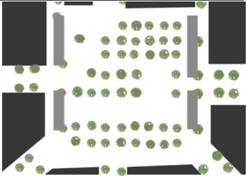

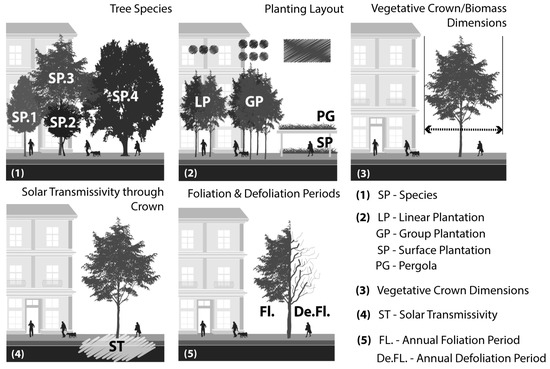

At local scales, and within the scope of public space design, very little work has been carried out on vegetation influences at a micro level and how such contributions can positively influence the thermal comfort of users within the public realm [40]. To better grasp this relationship, it is here suggested that five characteristics need to be addressed when using vegetation as a direct means to cool Tamb and/or reduce solar radiation. Each of these characteristics is visually presented in Figure 3 and shall be associated with each project to construct and organise these specificities within the Green MRF (MRF 1). When certain characteristics were not included within the particular study, when available, different references were used in order to provide the reader an indication of such vegetative specifications.

Figure 3.

Vegetation crown dimension according to surface and human exposure characteristics.

MRF 1.

Urban Vegetation.

As a starting point, the first characteristic relays to the type of vegetative species used in each of the projects, thus giving an overall comprehension of the tree characteristics. So far, the stipulation of tree species has already been used by various authors to study local effects on solar transmissivity [13,48,106,107,108,109,110].

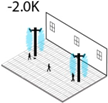

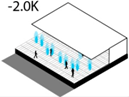

The second characteristic pertains to type of vegetative configurations and biomass (or vegetation coverage) utilised in each project. Such a stipulation was based on the study of Torre [111], who analysed the potentiality of using vegetation to modify outdoor microclimates, and moreover, to frame such potentials into design guidelines. These configurations were seen to be explicitly pertinent to the design of the public space in order to modify/optimise encircling microclimates, namely: (i) Linear Plantation (LP)—which is able to deflect radiation and wind currents; (ii) Group Plantation (GP)—which is able to deflect larger amounts of radiation and wind currents; (iii) Surface Plantation (SP)—which is able to change albedo, emissivity, and thermal storage/conductance; (iv) Pergola (PG)—which, depending on its configuration, is able to deflect radiation and wind. Pertaining to each configuration, similar results were also discussed in [112,113,114,115,116,117].

The third characteristic displays the dimensional features of the trees within each of the projects, including their crown spread, height, and growth speed. Such singularities become essential when determining the microclimatic contributions that the respective tree can present within the specific space. The fourth characteristic presents the vegetative shading coefficients of each species used in each project. As shown in the early studies conducted by McPherson [114] and Brown and Gillespie [117], different tree species vary considerably in transmissivity as a result of twig/leaf density and foliage development. Thus, and when available, the Solar Transmissivity (ST) is presented by percentage for each project/tree both for the summer and winter months.

The fifth characteristic provides information on foliation periods and seeks to present actual annual foliation and defoliation months for each species in the projects. Considering the case of deciduous trees as an example, although they may provide shade in the summer and permit solar exposure during the winter, they may not always provide shade precisely where desired, and the period in which many trees lose their foliage may not coincide with heating season at a respective location [48,116].

With regard to presenting the thermal results, as with all of the other MRFs discussed in this study, it is important to note that such reduction values were methodically approached differently by the authors in each project. In the interest of maintaining as much uniformity as possible, maximum reductions values (when available) were presented. In addition, such results were predominantly pertinent to the summer period, and, in most cases, were obtained on the same day or over the course of a set of specific days.

4.1. Introduction of Projects

Within this section, the discussed projects shall be divided into two types: (1) scientific oriented—which explores how existing trees can reduce Tamb, either at their existing state or by tweaking their characteristics; and (2) design oriented—which explores the effects caused by the introduction of new trees as part of a wholesome bioclimatic project.

4.2. Scientific Oriented Projects

The studies were further sub-divided into two categories: those that identified the In-Situ (IS) effects of vegetation on site and those that evaluated the effects of Park Cool Islands (PCI) in which Tamb was evaluated against an adjacent stipulated ‘comparison site’. Within such studies, the effects of IS and PCI were compared between areas principally cast in the shade by the vegetative crown and those generally cast in the sun. As this study was more focused on the direct influences of vegetation within a specific site, a larger emphasis was directed at the former. Nevertheless, some examples of PCI studies were also included based on the evaluated Tamb deviations, disclosed vegetation information, KG climate subgroups, and study scale. Outside of these established parameters, additional studies that have identified PCI Tamb variations between 1 °C and 3.8 °C can be consulted (e.g., [1,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126]).

4.2.1. IS Effect Studies

At a pedestrian level, the study conducted by Picot [127] revealed that the growth of street trees led to a reduction in Global radiation (Grad) as result of their incremental screening potential through their foliage, which reduced the amount of solar absorption on pedestrians within an outdoor plaza in Milan. Although the study revealed important thermal results through the use of the COMFA model, such energy budget results without a transposal upon more common measure units (such as °C) led the outcomes of the study to be harder to interpret for those less familiar with such budget thresholds (Project#1.1). Also, examining the screen potential of vegetation, Tsiros [40] analysed a limited set of Tamb measurements under tree canopies at a height of 1.70 m (slightly higher than the commonly applied height of 1.1 m) to examine the effect of shade trees within streets, which revealed different vegetative shading percentages. Grounded on a recognised limited set of data points, it was identified by the study that in a canyon (with a H/W of ≈0.90) with a shading area of 48%, the cooling effect was of a Tamb of 2.2 °C (Project#1.2). Also, considering other variables such as V and RH, and within a same climate subgroup, Taha, Akbari, et al. [128] revealed that vegetation could result in a Tamb decrease of up to 1.5 °C within a cluster (or GP) of orchards. It should be noted, however, that such results were obtained within an open field, and such results were recognised to likely vary within a more urban setting with a different morphological setting (Project#1.3). Nevertheless, and conducted within an urban setting in Melbourne, Berry, Livesley, et al. [115] identified a similar Tamb reduction of 1 °C as a result of a dense potted tall tree canopy in close proximity to a building façade. Although influences on other variables such as Tsurf were also considered, it was recognised that a future study was needed to identify influences on additional variables. Such a necessity can be attributed to the low reductions in Tamb, which were likely due to atmospheric conditions diluting the magnitude of the presented results (Project#1.4).

In a different way to the previous four projects, Shashua-Bar, Tsiros, et al. [129] reported the potential of vegetative cooling through the use of thermo-physiological indices in addition to Tamb reductions. Within their study, four theoretical design interventions within Athens were examined to explore how different PSD means could influence pedestrian thermal comfort levels. Of the four, the two most successful solutions were (i) to increase vegetative coverage from 7.8% to 50%, and (ii) to elevate building façades by two additional floors, thus changing the Height-to-Width (H/W) ratio from existing 0.42 to 0.66. The increase in vegetation coverage demonstrated Tamb/PET reductions of 1.8 °C/8.3 °C (Project#1.5). Also established using additional variables (e.g., W/m2, Mean Radiant Temperature (MRT), and (iii) within the city of Hong Kong, Tan, Lau, et al. [130] recently studied the use of urban tree design to mitigate daytime UHI effects as a result of the city’s elevated urban density. It was identified that in locations with a high Sky View Factor (SVF) (i.e., with a low H/W ratio), the presence of a group of vegetation could lead to a maximum Tamb/MRT reductions of 1.5 °C/27.0 °C (Project#1.6). It was, however, identified that further study was required to examine the presence of other tree species to present more concrete recommendations for the urban placement of different tree species. Obtaining a comparable Tamb reduction in the city of Manchester, Skelhorn, Lindley, et al. [131] also identified a comparable reduction of 1.0 °C during the summer by increasing the amount of existing mature trees on site (Project#1.7). In addition, the study identified the risks with calibrations of ENVI-met [132] simulations in representing accurate readings of real-worlds measurements, as also identified in [133].

In addition to these projects, it is also worth noting that there were numerous studies that were not included in the framework due to (1) the identified Tamb reductions being <1.0 °C; (2) being located outside of stipulated KG climate subgroup; and (3) the analysis being set a larger meso/macro scale. Nevertheless a critical overview of their selected results is summarised below:

- Tsilini, Papantoniou, et al. [134] identified that the hours revealing the greatest variations as a result of vegetation were between 12:00 and 15:00; (ii) Martins, Adolphe, et al. [135], who also identified low reductions of Tamb, presented noteworthy thermo-physiological reductions (e.g., a PET decrease of 7 °C); (iii) similarly, and by combining with other PSD measures, Wang, Berardi, et al. [136] also identified similar PET reductions of 3.3 °C and 4.6 °C even when reductions of Tamb did not surpass that of 1.0 °C

- Abreu-Harbich and Labaki [137] identified that the most predominant influence on thermal comfort was the tree structure, regardless of the utilised thermal index (i.e., PMV and PET); (ii) in a later study, Abreu-Harbich, Labaki, et al. [138] again identified both the importance of tree species and the use of thermo-physiological indices such as PET for evaluating thermal comfort; beyond considering Tamb, they also considers factors such as solar radiation dynamics

- Through satellite imagery, Jonsson [139] discovered that at a larger scale, urban Tamb varied between 2 °C and 4 °C as a result of the presence of vegetation; (ii) in the study conducted by Perini and Magliocco [140], it was also identified that at ground level and as a result of foliation, Tamb, MRT, and PMV values were also considerably lower (≈−3.5 °C in Tamb and −20.0 °C in MRT) in comparison to those identified in the rest of the city; and, finally, (iii) in an effort to determine influences of urban vegetation on local conditions within high density settings, Kong, Lau, et al. [141] identified maximum reductions of 1.6 °C in Tamb, 5.1 °C in MRT, and 2.9 °C in PET.

Although the disclosed studies were not included within the Green MRF, their results highlight the importance of vegetation even when variables such as Tamb varied beneath 1.0 °C, within other KG subgroups (i.e., within different climatic circumstances), and lastly, at larger urban scales in which the effects of vegetation are still salient when addressing high urban temperatures and UHI effects.

4.2.2. PCI Effect Studies

Accounting for the fact that the following studies compared the PCI effects with adjacent areas with generally no (or significantly limited) vegetation, the ensuing studies revealed higher reductions of local human thermal stress. Shashua-Bar and Hoffman [142] selected 11 outdoor public spaces in Tel-Aviv (located within a KG subgroup of ‘Csa’) and identified that (i) in all locations, the maximum cooling effect from trees took place at 15:00, and (ii) the average Tamb cooling effect throughout the sites was of 2.8 °C, with a maximum of 4.0 °C (Project#1.8). A decade later, and still located in Tel-Aviv, the analysis carried out by Shashua-Bar, Potchter, et al. [107] also illustrated similar cooling potential from common street trees. When reaching their full vegetative biomass, and within a canyon with a H/W of 0.60, the cooling effect of the selected trees attained Tamb reductions of up to 3.4 °C (Project#1.9). A further study conducted in Tel-Aviv by Potchter, Cohen, et al. [143] also identified an almost identical Tamb reduction of 3.5 °C resultant of an urban park containing large high and wide trees (Project#1.10). A similar reduction was also identified by Skoulika, Santamouris, et al. [144] within an urban park in Athens ‘Csa’, who revealed a Tamb reduction of up to 3.8 °C (Project#1.11). Lastly, and also within a ‘Csa’ subgroup, Oliveira, Andrade, et al. [145] also identified a very strong and clear PCI effect within small urban park in Lisbon. The identified effect was determined within an urban built-up area (2479 buildings/km2) within a district with an orthogonal urban geometry, with a small 95 × 61 m urban park centred between the urban blocks. In their study, and during specific days, it was identified that the green space led to reductions of 6.9 °C in Tamb, 39.2 °C in MRT, and 24.6 °C in PET (Project#1.12).

4.3. Design-Oriented Projects

Leaving the scope of scientific exploratory projects, the Parisian climate sensitive redevelopment project, ‘Place de la Republique’ aimed to address both pedestrian thermal comfort and UHI within the largest public space in Paris (Project#1.13). Although exact temperature reductions were not identified, the strategy consisted of implementing measures that would increase vegetative biomass in order to influence solar permeability and provide protection from winter wind patterns [146]. Similarly, and within a ‘Csa’ subgroup, the ‘One Step Beyond’ winning proposal for the international ‘Re-Think Athens’ competition also used vegetation to cool Tamb within the public realm (Project#1.14). As part of a defined ‘heat mitigation toolbox’, the proposed greenery, such as grass, hedges, climbing plants, and trees, was aimed at mitigating the UHI effect through evapotranspiration and vegetative shading [147]. Still, within a ‘Csa’ subgroup, a rehabilitation project was introduced in order to improve the environmental resilience to the intense summer sun and temperatures within Almeida de Hercules in Seville (Project#1.15). As part of the intervention, additional vegetation was introduced with a planting structure varying from LP to GP depending on the uses and activity threads. Lastly, located in Barcelona, the winning submission ‘Urban Canòpia’ aimed at proposing a new park-plaza that would introduce new contemporary dimensions, including means to address the thermal comfort levels (Project#1.16). The principal measure used was vegetation, in order to diminish Tamb and limit the amount of solar radiation during summer.

4.4. Critical Outlook

When approaching the effects of vegetation within the local public realm, it is clear that they provide numerous benefits within the built environment. Nevertheless, when approaching issue of thermal comfort, the identified quantity and type of effects depend predominantly on (i) tree characteristics, planting layout, and site conditions; and (ii) the utilised evaluation methods/variables. These two facets have been respectively summarised within the Green MRF.

When considering the results obtained by Projects#1.5/6, it was possible to identify that while IS Tamb reductions were low, thermo-physiological variables revealed substantial influences on thermal comfort thresholds. As a result, it is reasonable to assume that such influences would also be verified within Projects#1.2/3/7. As already discussed, such variances were also identified in studies that witnessed reductions of <1.0 °C and that were also located within different climate subgroups. When considering studies that identified PCI effects, similar conclusions could be drawn between Projects#1.8–12. Nevertheless, it was noted that the PCI effects generally rendered greater reductions of Tamb due to the greater cluster and/or arrangement of vegetation within the respective ‘green site’. However, PCI studies also revealed comparably higher reductions in thermo-physiological variables (i.e., of up 24.6 °C in PET) as demonstrated by Project#1.12.

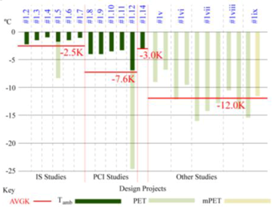

Within Table 5, and when available, the thermal results of each project were plotted to illustrate the maximum and average attenuation capacity (in Tamb and PET) between the IS studies, design project, and PCI studies. Adjoining these studies, the selected results from five additional studies were also plotted within Table 5. As they were either located within other KG subgroups, or more oriented towards thermo-physiological aspects, they were not included within the Green MRF. Within the last project of the five (Project#1ix), [77] revealed both the IS influences of PET and mPET from the Tipuana tipu, also within a ‘Csa’ subgroup, in common default urban canyons within the historical quarter of Lisbon. The results from the additional studies served to demonstrate how thermo-physiological indices significantly varied IS, as they considered additional factors such as solar radiation. Additionally, and as verified by earlier studies (e.g., [9,13,114]) and confirmed by the reviewed studies in this section, Tamb variations as a result of vegetation can prove to be a less efficient method of evaluating thermal comfort conditions at pedestrian level as the encircling atmosphere quickly dissolves such variations.

Table 5.

(A)—Supplementary study results that identified vegetation effects on PET. (B)—Overview of maximum and average reductions of Tamb and PET.

5. Sun Measure Review Framework

Again pertaining to the microclimatic characteristic of solar radiation, its intrinsic relationship with H/W with regard to local thermo-physiological thresholds has also received considerable attention within the scientific community. Amongst others (e.g., [160,161,162,163,164,165,166]), a summary of studies regarding canyon and bioclimates is summarised in Table 6, including those from other climate subgroups and those described in Table 1/Figure 1. Although the Sun MRF (MRF 2) deliberates specifically on the implementation of shelter canopies, Table 6, beforehand, presents selected outputs from such studies to inspect the broad-spectrum relationship between H/W and that of local thermo-physiological thresholds.

Table 6.

Review of studies that identified thermal results from H/W and canyon analysis.

MRF 2.

Shelter Canopies.

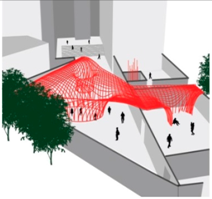

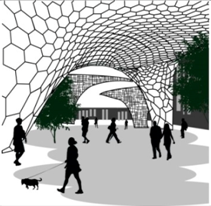

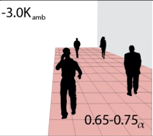

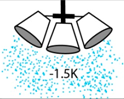

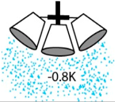

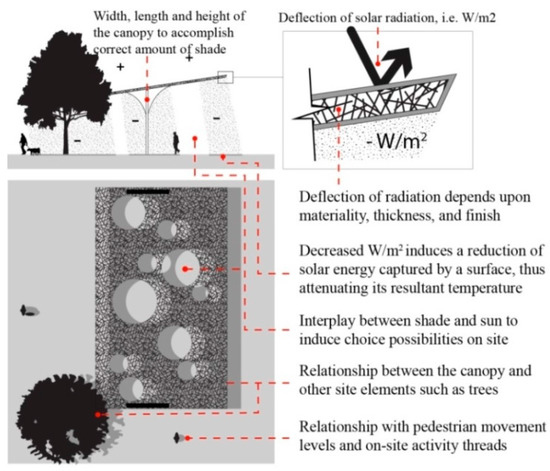

From the studies presented in Table 6, two critical aspects were identified with regards to the relationship between urban canyons and solar radiation, namely, that (1) canyons within different aspect ratios, symmetry, and orientations can present acutely different influences on thermal comfort thresholds; and (2) within the canyons themselves, such thresholds can also vary significantly. For this reason, and given that the modification of H/W is often unfeasible within existing urban frameworks, PSD plays an important role in addressing such a limitation during annual periods of high thermal stimuli. Thus, and when addressing shade canopies and/or structures within public spaces, the main microclimatic factor that must be considered is its ability to address solar radiation. Although the correlation between solar radiation and Tamb can be deceptive, MRT has proven to be a complicated, yet effective, variable for understanding the effect of solar radiation in outdoor contexts [173]. Placing this within IS terms, while the registered Tamb under a canopy may be the same as one fully exposed to the sun, the amount of solar radiation will differ significantly. As a result, this variation in radiation will dramatically influence MRT, and thus, influence pedestrian thermo-physiological comfort levels. This being said, and within Figure 4, the broad characteristics of shelter canopies and their influence on respective variables (namely W/m2) are generally described from a design point of view.

Figure 4.

Variables that influence the performance of shade canopies.

5.1. Introduction of Projects

Currently, the use of shade canopies in the public realm is far from uncommon. However, and similar to the use of vegetation, very few of them originate as a result of a wholesome bioclimatic approach, and are often a product of urban ‘cosmetic beautification’. In order to effectively examine the use of shade canopies as a means of attenuating thermal comfort levels, a differentiation between short-term and long-term interventions is required. Unlike most of the other thermal PSD measures, the design of shade canopies can be often interlinked with temporary solutions. Here, the design of the structure itself can be oriented as an Ephemeral Thermal Comfort Solution (ETCS) [28], which can provide short-term solutions during annual periods of higher thermal stimuli. When considering ‘Temperate’ climates and their general solar radiation implications on Mediterranean cities, one must similarly consider that there is an increased need for solar radiation during the winter as well. Resultantly, the implications between ETCS and permanent shading solutions are considerably different. While ETCS are only directed at addressing the need for solar attenuation during the hotter months, permanent solutions must also be evaluated in terms of their impact during winter periods, in which increased solar exposure often becomes more desired. Both typologies shall be incorporated into the Sun MRF to describe how the selected design solutions were elaborated by others to attenuate the amount of thermal human stress within the respective outdoor spaces.

5.2. ETCS Projects

Now concentrating on the ETCS scope, both the Mediterranean countries of Portugal and Spain have proposed creative and temporary solutions through the application of nylon in order to address the summer sun and simultaneously contribute to the quality of the urban public realm. Initiated in 2011, ‘Umbrella Sky Project’ was launched in order to decrease the amount of heat stress on the pedestrians throughout July to September (Project#2.1). Similar in nature, Madrid also deploys ETCS during the hotter months of the year in order to decrease the amount of solar radiation felt by pedestrians, exemplified in shopping streets such as ‘Calle del Arenal’ (Project#2.2). In addition, although not included within the MRF due to a lack of available specifications, a similar approach was also applied within the Spanish city of Seville, known as ‘Calle Sierpes’ within a commercial street to also reduce radiation fluxes at pedestrian level.

In 2008, and within Madrid, the conceptual project ‘This is not an Umbrella’ (Project#2.3) mimicked the idea shown in Project#2.1. Although a simple and low-cost solution, it enabled a way in which to attenuate thermal comfort levels in the patio of the Spanish Matadero Contemporary Art Centre. A similar approach was also undertaken in a contemporary art centre with the use of freshly cut bamboo to provide relief from the hot summers in New York (Project#2.4).

In an effort to explore the installation of light-weight and movable shading canopies, the recent project ‘Urban Umbrella’ in Lisbon also sought to introduce means of providing relief from the summer sun (Project#2.5). Resultant of their design, the pedestrians could open or close the canopies depending on their preference or time of stay within the exterior space. Lastly, Ecosistema Urbano architects launched a conceptual ‘Bioclimatic urban strategy’ to improve the pedestrian comfort in the public spaces of downtown Madrid (Project#2.6). Of the numerous measures proposed in the strategy, various types of canopies were suggested, including sheets of fabric/foliage supported by roof-cables and small shade canopies that were to be placed above new seating amenities within the different squares.

5.2.1. Permanent Solution Projects

The following projects illustrate cases in which permanent shade solutions were projected and/or constructed. The first project refers back to the ‘One Step Beyond’ project entry (Project#1.14), where in one of the public spaces (Omonia square), a limited number of shading canopies were introduced. Although the four canopy structures shade less than 10% of the total area of the public space, they were strategically placed adjacent to food/beverages kiosks. Consequently, the associated risk of over-shading during the winter is null, and effective shading is accomplished year round. Still, within the ‘Re-Think Athens’ competition, another noteworthy entry was the ‘Activity Tree’ by ABM architects (Project#2.7). After an in-depth site analysis, the zones that would require attenuation from solar radiation were to be protected by ‘Bioclimatic Trees’. These structures were designed to permit solar penetration during the winter through a structural celosias system.

Within Seville, and also resultant of an international competition, the proposal ‘Metropol Parasol’ introduced a significantly larger structure and provided actual uses within its interior (Project#2.8). The principal idea behind the project was to offer shade within the previously sunny and hot square, and to enable more activity threads during the summer. Also in Spain, the last project is located in Cordoba, with a large open space that lacked shading measures and fell victim to elevated summer temperatures. As a result, ParedesPino architects installed prefabricated circular canopies that vary in height and diameter in order to represent that of an ‘urban forest of shadows’ (Project#2.9).

5.2.2. Critical Outlook

As shown within the Sun MRF, very few constructed projects have considered the thermo-physiological implications of either ephemeral or permanent shade canopies; thus, the inclusion of ‘Thermal Results’ was not justified. Nevertheless, and as exemplified by Projects#2.1–6, although the use of ephemeral shade canopies was perhaps more predisposed to artistic influence rather than precise scientific application, it can be safely assumed that their continual use is indicative of their capacity to reduce thermal stress levels. Although the quantification of such a reduction within these projects has not yet been identified or disseminated, two recent bioclimatic PSD studies examined how ephemeral shade canopies were able to concretely reduce IS thermo-physiological thresholds. These two studies were undertaken within two different urban canyons types, and are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Result review of two bioclimatic studies that identified concrete thermo-physiological attenuation as a result of ephemeral shade canopies.

In Project#2viii, the study examined how the presence of canopies could reduce pedestrian thermal stress during the summer in a civic square (Rossio) in Lisbon by examining potential reduction of Grad (W/m2) within the lateral area of a canyon with a low aspect ratio. As revealed by the study, (i) the introduction of nylon canopies resulted in a projected MRT/PET decrease of 20.0 °C/9.9 °C within the eastern sidewalk at 15:00, an area prone to high physiological discomfort during the afternoon (results which are concomitant with the study outcomes presented in Project#2ii/vii); and, (ii) the introduction of opening/closing permanent shelters similar to those presented in Project#2.5 and constructed out of aluminium acrylic presented a potential MRT/PET reduction of 22.0 °C/12.3 °C within the centre of the canyon. Similarly, and as identified within Project#2ix, the study identified the effects of two ephemeral shelter canopies (identified as sun sails) on thermal comfort levels within two types of canyons in Pécs, Hungary. Within the first and lower canyon, maximum MRT/PET reductions were of 11.0 °C/5.0 °C, and the higher canyon revealed even greater reductions of 27.0 °C/13.0 °C.

Naturally, each project should be approached on a case by case scenario. However, the projects in Table 7 reveal a slightly different approach to those presented within the Sun MRF, as they considered concrete thermo-physiological impact that the shelters would have on pedestrians. As a result, it is thus suggested that further approaches and research of this nature are necessary with regard to the implementation of this type of PSD measure. Such a necessity becomes especially prominent for projects that utilise permanent shelter canopies and, moreover, when the canopies overcast a high percentage of the space (e.g., Project#2.8/9). In such cases, it becomes adjacently vital to consider how such shadows may lead to risks of over-shading within ‘Temperate’ winters, in which higher levels of solar radiation are often desired by pedestrians.

6. Surface Measure Review Framework

So far, the application of ‘cool materials’ in PSD has also progressively explored means to counterbalance elevated temperatures and UHI effects. More specifically, these materials are those that contain both high reflectivity and thermal emissivity values, thus performing better when exposed to high solar radiation and ambient temperatures [175]. Resultantly, the application of materiality on urban surfaces encounters its niche within the design and conceptualisation of the urban realm in ‘Temperate’ climates. Thus far, there has been considerable exploration into the increase of pavement albedo through the improvement of surface coatings and the use of aggregates/binders with lighter colours. Based on the study conducted by Santamouris [176], these examples include white reflective paint, infrared reflective coloured paint, heat reflecting paint, and, lastly, colour changing paints on pavement surfaces. The results of these studies showed considerable Tsurf decreases of up to 24 °C during the day.

6.1. Introduction of Projects

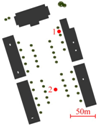

In parallel to the discussed global studies regarding the thermal benefits of high albedo and emissivity materials, several bioclimatic projects have thus far incorporated such approaches to cool local temperatures and attenuate UHI effects. In these projects, the design goes beyond the execution of improved pavements and considers their integration within a wholesome design project to address thermal comfort levels. All of the projects in this section are situated within a climate KG subgroup of ‘Csa’ and, interestingly, in either Athens or Tirana.

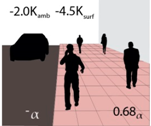

Approached as a bioclimatic rehabilitation project in Athens, in an effort to also attenuate temperature and UHI effects, Santamouris, Xirafi, et al. [177] demonstrated a Tamb reduction of 2.0 °C through the increase of shaded surfaces, evapotranspiration effects, and utilisation of cool materials (with albedo values ranging between 0.70 and 0.78) (Project#3.1). Also currently being constructed and located in Tirana, Fintikakis, Gaitani, et al. [178] investigated the use of cool pavements (the predominant PSD measure) that exceeded an albedo value of 0.65, along with the combination of other measures such as the increase of greenery and shading canopies, in an effort to achieve a Tamb reduction of 3.0 °C and reduce peak temperatures (Project#3.2).

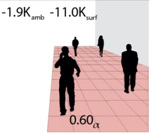

Returning to Athens, Gaitani, Spanou, et al. [19] studied the application of cool pavements in streets and squares in order to alleviate both Tsurf and Tamb. Adjoining the changing of pavement materials, there was also an increase of vegetation and shading canopies. Yet, and similarly to the previous projects, these alterations were also secondary to the changing of pavement materials. The intervention led to an overall Tamb decrease of 2 °C and also improved temperature homogeneity within the public realm (Project#3.3). Similarly, and as part of the rehabilitation of an urban park within Athens, Santamouris, Gaitani, et al. [175] changed the dark paving to pavements coloured with infrared reflective cool paints (presenting an albedo of 0.60), which led to a Tsurf/Tamb decrease of up to 11.3 °C/1.90 °C (Project#3.4). Adjoining to these studies within Athens and Tirana, other existing studies also within the ‘Temperate’ group revealed similar Tamb reductions of between 1.0 °C and 2.5 °C through pavement modification [179,180,181].

Similar to Projects#3.1–4, the two subsequent projects also integrate the use of materials as part of their bioclimatic approach. This being said, the use of materials has the same weight as other measures such as the implementation of vegetation, shading canopies, and water/misting systems. Both have already been mentioned in the previous sections/MRFs, yet also integrate cool pavements in their bioclimatic approach. The Parisian environmental redevelopment plan (Project#1.13) utilises the use of perennial materials, and the effects of UHI were directly used as a design generator to reconfigure the area’s surface materials, whereby (i) the shaded zones of the square were predominantly in darker colours, and (ii) the open spaces were paved primarily with generally paler colours [146]. Along the same lines, the ‘One Step Beyond’ proposal (Project#1.14) also uses cool materials such as light asphalt, light concrete, and light natural stones specifically for their high albedo value and lesser absorption of radiation [147].

Within the Surface MRF (MRF 3), all of the bioclimatic projects that use materials to cool Tsurf/Tamb were presented. With exception for the Project#1.13, all projects were implemented in public spaces that have hot-summer Mediterranean climates. The projects in this framework consider the energy balance of the pavements, namely, by (i) increasing albedo values, thus decreasing absorption of solar radiation on the materials; and (ii) decreasing the amount of radiation that the materials were exposed to by the presence of new shading measures (not shown in icons for simplification purposes). Both stone (marble) and concrete (with IRCP) surfaces led to the greatest increases of albedo as shown in Projects#3.1–4/1.14. More specifically, and as can be seen by the projects, the substitution of surface materials increased albedo by up to 51% (Project#3.1) and led to an overall Tamb/Tsurf reduction of up to 3.0 °C/11.0 °C (Projects#3.2/4, respectively).

MRF 3.

Materials.

6.2. Critical Outlook

When considering materiality interventions within PSD, and similarly to most fields within the spectrum of climatic adaptation, disagreement has arisen within the scientific arena. When approaching the urban canyon, certain authors have suggested that the decrease of temperatures referring to urban surfaces (such as pavements) may, in fact, not lead to a decrease in Tamb and, moreover, to ‘adverse human health impacts’ [182]. Such authors have also advised that the refection of radiation from high-albedo pavements can also (i) increase the temperature of nearby walls and buildings, (ii) augment the cooling load of surrounding buildings, (iii) lead to heat discomfort felt by pedestrians, and (iv) induce harmful reflected Ultra Violet (UV) radiation and surface glare issues.

Notwithstanding, this reflection suggests that these disagreements do not justify the hindrance of both the development and further incorporation of reflective pavements, including those of cool pavements. As illustrated by Project#3.3, researchers and manufacturers have also been developing cool coloured materials with higher reflectance values compared to conventionally pigmented materials of the same colour. Encouragingly, such materials have been applied in cases in which the use of light colours may lead to solar glare issues, or simply when the aesthetics of darker colours are preferred. Lastly, and unlike pavements, the thermal attenuation of building surfaces has been well documented; thus, if a wall or building surface is affected by the pavement’s increased reflectivity, the buildings surface is, arguably, in itself thermally inefficient.

When considering the urban energy balance as suggested by Oke [16], factors such as urban heat storage (ΔQs) play a very important role within the urban environment. For this reason, and due to the shear amount of paving within the public realm, its heat flux has been a topic of study as identified within Surface MRF. More specifically, and due to the consensually established poor performance of materials such as asphalt and concrete, methods to increase pavement albedo are continually being explored, namely through modifying surface coatings and the aggregates/binders with lighter colours. Yet, another important aspect identified within Projects#3.1–4/1.14 was the integration with other PSD measures.

Thus, it can be suggested that PSD measures such as pavements should be approached as a two-step approach, whereby, depending on the identified susceptibility to solar radiation (i.e., as a result of IS aspect ratio and/or sky view factor) they could (1) integrate other PSD measures that can, beforehand, reduce the energy load upon the pavement; and (2) improve the thermal balance of the pavement. Based on the results obtained by Projects#3.1–4, such a pavement thermal balance can be approached by specifically considering their (i) absorbed solar radiation; (ii) emitted infrared radiation; (iii) heat transfer resultant of convection into the atmosphere; (iv) heat storage by the mass of the material; (v) heat conducted into the ground; (vi) evaporation or condensation when latent heat phenomena are present; and, lastly, (vii) anthropogenic heat caused by frequent urban factors such as vehicular traffic. As a result, and similar to the projects mentioned in the Green/Sun MRF, to accurately approach such cooling effects, variables such as Tamb and Tsurf should be complemented by thermo-physiological indices to assess the influences of non-temperature elements on human thermal comfort as well.

7. Blue Measure Review Framework

In the past, the presence of water and misting systems was customarily focused on aesthetic and sculptural purposes in PSD. More recently, however, there has been a considerably greater emphasis on their interconnection with bioclimatic comfort in outdoor spaces in terms of adaptation efforts to climatic conditions [183]. For this reason, water and misting systems have since taken on a new meaning.

7.1. Introduction of Projects

Perhaps due to its early integration, the arena of existing projects has the tendency to fall into two predominant typologies. The first type, which is more oriented towards design, often falls short of explaining how their integrated water/misting systems can attain the correct balance between RH levels and those of Tamb. On other the hand, the second type, predominantly from Japanese literature, mostly focuses on the engineering aspect of equilibrating humidity levels with temperature thresholds and is less design oriented. Neither of these types is more important than the other, but this presents the opportunity to learn from both approaches in order to improve the incorporation of such PSD measures.

7.2. Design Oriented Approach

The first examples return to the Parisian and Athenian design projects (Projects#1.13–4), which also incorporate the use of water and misting systems as part of their wholesome bioclimatic approach. In Project#1.13, the use of water is not only utilised for aesthetic purposes but to address elevated temperatures during the summer. Project#1.14 integrates a ‘Heat mitigation Toolbox’ that implements the evaporation of micro water particles in order to reduce extreme temperatures and UHI effects.

Within Lebanon, Nunes, Zolio, et al. [183] propose to re-develop Kahn Antoun Bey in Beirut. The dominant conceptual bioclimatic measure used in the proposal was a misting system, which, in combination with other measures (i.e., vegetation, materiality, and canopies), was designed to tackle hot, yet humid, summers. Integrated within the study, an initial indicative expression was used to determine cooling effectiveness ranges based on Tamb, RH, and water temperature. As a result, after considering the high RH levels inherent to the site, it was considered that its microclimate could jeopardise the misting system (Project#4.1). Such a conclusion hence suggests that water spraying requires careful deliberation and thus will be analysed further within the ensuing projects.

Returning to the European context, the Expo of 1992 in Seville (Project#4.2) was approached as a method for synthesising bioclimatic techniques with PSD. Various innovative techniques are focused on the application of misting systems and bodies of water, namely, through (i) continuous blowing of moist air, (ii) ‘micro’ water nozzles in trees and structures, (iii) ‘sheets’ of water in the form of ponds and waterfalls [184,185]. In comparison with all of the other design-oriented projects, this project also accommodated a relatively strong engineering approach, yet it lacks the applicative detail that is presented by engineering projects discussed in this review article. Moreover, the project is also a case in which Surface Wetting (SW) is undesired, as it was argued that it would lead to stagnancy and resource wastage. However valid, such an approach should not lead to the conclusion that SW cannot be integrated within the systems overall design.

As an example of this incorporation, and situated within a ‘Cfb’ climate, the French project ‘Le Miroir d’Eau’ (Project#4.3) was based on the concept of addressing thermal comfort levels and reflecting surrounding façades through a sheet of water and an integrated misting system (also based on a ‘micro’ nozzle system). To address the issue of stagnation, the water that temporarily floods the slabs is recollected after a few minutes, leaving the pavement surface dry. Through this method, wet surfaces become part of the design of the system, one which increases the climatic responsiveness of the once thermally problematic public space.

To finalise the design projects, and returning to the ephemeral perspective, one can also refer to the ‘CoolStop’ implementation in New York (Project#4.4). Simple in concept, constructed out of PVC piping, and operated through a fire hydrant unit, the misting system cooled the encircling microclimate during the summer months. Resultant of its ephemeral nature, resource wastage and stagnation was far less of a concern due to its on/off nature, seasonal use, and low consumption requirements.

7.3. Engineering Oriented Approach

In many cases, SW is undesired not only due to wastage/stagnation concerns but also because it can represent a direct result of exacerbating acceptable RH levels, in which water particles are unable to evaporate due to high atmospheric moisture content. As a result, this can lead to an undesired wetting sensation upon pedestrians. In order to effectively lower Tamb without imperilling acceptable humidity levels within PSD, the appropriate water pressure, nozzle type, and functioning period must be established [17,28,54].

As attested by Ishii, Tsujimoto, et al. [186] and Ishii, Tsujimoto, et al. [187], the formation of correct droplets with the adequate amount of temporal intervals becomes fundamental when approaching thermal comfort in areas that witness high humidity levels. Resultantly, and in order to explore these techniques a little further, the following projects are those that have adapted more of an engineering approach when establishing concrete temperature reductions through misting systems.

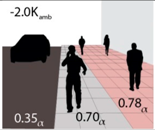

With goal of learning from ancient Japanese rituals such as ‘Uchimizu’, Ishii, Tsujimoto, et al. [187] developed an exterior misting system that would enable the reduction of air-condition loads without the use of vegetation (Project#4.5). Since Japan has a humid climate (i.e., ‘Cfa’), the system was designed to overcome high humidity whilst decreasing high ambient temperatures, hence the name ‘Dry-Mist’. Within an outdoor environment, it was projected that (i) for every 1 °C drop in Tamb, RH would increase by 5%; and (ii) the system could lead to a total Tamb decrease of 2 °C that, subsequently, would lead to a reduction of 10% in energy consumption of interior air conditioners.

Situated within a different setting, (Project#4.6) takes the exploration of the ‘Dry-Mist’ system a little further; installed within a semi-open train station during the summer of 2007, a total of 30 nozzles were implemented in order to test their cooling effect. In their study, Ishii, Tsujimoto, et al. [186] reported an initial cooling potential Tamb average between 1.63 °C and 1.90 °C between 9:00–13:00, and 13:00–15:00, respectively. Nevertheless, and beyond these mean values, the maximum decrease in Tamb reached 6.0 °C and was accompanied by an increase of 28% of RH. These results illustrate that the consequential increase in humidity, although not in a fully exterior setting, accurately follows the ratio established in Project#4.5 (i.e., −1 °C in Tamb = +5% of RH). Similar to the application of cool pavements discussed in the previous section, there is limited knowledge regarding actual design and installation. An issue that often arises in this respective quandary is linked with the optimum amount, and size, of particles (i.e., the Sauter Mean Diameter (SMD) of the water particles).

To specifically address this issue of micro water droplets, Yamada, Yoon, et al. [188] discussed the cooling effect/behaviour of different particle sizes utilised within misting systems in outdoor spaces (Project#4.7). Through Computational Fluid Dynamic (CFD) studies, it was demonstrated that there is minor deviation in temperature for different particles sizes. Three different cases of SMD were examined, i.e., 16.9 μm, 20.8 μm, and 32.6 μm, and each displayed a similar Tamb reduction of ≈1.5 °C. Nonetheless, it was also identified that, due to their size and increased water mass, larger particles remained longer and at a lower position, thus suggesting the importance of particle size when deciding on the height of the misting system, especially if in circumstances whereby SW is undesired.

To approach the issue of height variation, Yoon, Yamada, et al. [189] studied the performance of a misting system in a semi-outdoor space, with three sprays placed at 1.5 m from the ground (Project#4.8). Through the application of CFD studies, and by assuming a wind speed of 0.1 m/s and solar radiation of 363 W/m2, the following conclusions were reached: (i) Tamb of 30 °C with 80% RH scenario—water particles descended to near the ground before evaporating, reduction in Tamb of ≈2.5 °C; and (ii) Tamb of 30 °C/34 °C with 60% RH scenario—the water particles evaporated much faster, and led to a Tamb reduction of ≈1.75 °C. Resultantly, the study concluded that even if outdoor temperature was different, the distribution of the cooling effect would display similar behaviour; furthermore, when the RH exceeds 80% threshold, any misting system beneath that of 1.5 m will very likely lead to SW.

More recently, and carried out by Farnham, Nakao, et al. [190], both the pertinence of nozzle height and SMD was confirmed in Japanese city of Osaka (Project#4.9). Within a semi-enclosed space, this particular experiment achieved a total Tamb cooling of 0.7 °C without SW. This result was achieved by single nozzle spraying water particles with an SMD of between 41 μm and 45 μm. However, and even from heights of 25 m, if the respective SMDs were increased then an excessive amount of water particles would amalgamate close to the floor (thus exacerbating RH thresholds) and cause undesired SW.

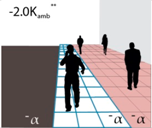

The Blue MRF (MRF 4) was constructed to discuss two types of projects: those that allow SW and those that do not. Projects#1.13, #1.14, #4.3, and #4.4 demonstrated how SW is incorporated into the system in order to avoid issues of stagnation or water wastage. On the other hand, scientific Projects#4.5–8 show how high humidity levels can be overcome when cooling semi-enclosed and outdoor public spaces when SW is undesired. In light of their technical approach, design-oriented projects can thus learn from their methodical resolutions when addressing high Tamb and UHIs. Promisingly, and based on the disclosed results, although the already high atmospheric moisture levels beneath the UCL could discourage such applications, as a general rule of thumb, this can be overcome by a combination of (i) the correct nozzle height (1.5 m≥), (ii) the appropriate ‘projected’ water particle size (i.e., with a SMD below 45 μm), (iii) functioning beneath a microclimatic environment with a RH of 70–75%, (iv) assuming an increase of 5% RH for every decrease of 1.0 °C in Tamb, and (v) avoiding the use of the misting system if the average wind speed surpasses that of 1 m/s.

MRF 4.

Water/Misting Systems.

Promisingly, all of the scientific Projects are located in a KG subgroup of ‘Cfa’, which also has a temperate climate and hot summers; its ‘f’ subgroup portrays a climate without annual dry seasons. When considering these implications on ‘Csa’ climates, and when cooling Tamb in dry summers, the evaporative cooling of water particles can thus be explored further without exacerbating acceptable RH levels.

7.4. Critical Outlook

As with all of the types of measures presented in the studies discussed in this review article, it is important to remember that outdoor environments should not be designed to mimic indoor conditions [185]. Analogously, when approaching outdoor contexts, it is vital to consider that pedestrians often avert microclimatic monotony and frequently expose themselves to environmental stimuli that can surpass identified thermally comfortable thresholds [54]. For this reason, the application of misting systems through PSD must not be seen as a means of simply reducing Tamb because they surpass a certain benchmark during the day. Instead, they should be approached as a means of reducing temperatures in certain locations which, in turn, can offer an increased thermal versatility within an outdoor space. Naturally, the placement of such locations needs to be correct based on similar approaches such as those conducted within Projects#2i–2vii. Once established, their dimension and installation can be more effectively considered with regard to installation specifications (e.g., whether nozzles are installed within floor slabs in the centre of the square or above pedestrian level within the tree crowns above sidewalks). Thus far, however, the concrete application of such measures within the scope of thermal sensitive PSD is still significantly divided between design approaches (often lacking technical experience, namely in Projects#1.13/4/4.1–4.4) and those of a more engineering approach (often lacking the design approach, namely in Projects#4.5–4.9). Accordingly, it is thus suggested by this review study that, based upon existing knowledge, there is the fertile opportunity for future studies to dilute such segregation, even if initially based on rudimentary rules of thumb such as those mentioned in this section.

8. Conclusions & Critical Research Outlook

Bottom-up approaches to climate adaptation are continually becoming more essential for local urban design and decision making. Although often derivative from the global system, it is within local scales that adaptation efforts find their niche for addressing both existing and future microclimatic aggravations. For this reason, and in parallel to top-down approaches and assessments disseminated by the scientific community, the union between fields of urban climatology and planning/design must continue to be strengthened.

Promisingly, and perhaps as a result of a synergetic relationship with the overall climate change adaptation agenda, means of addressing local outdoor thermal comfort thresholds are continually increasing. Within this review article, such a development within the state-of-art has been based on the identification of how PSD can address thermal comfort thresholds in climates with the KG group of ‘Temperate’. Within this class, the subcategories of ‘Cfa’, ‘Cfb’, and ‘Csa’ were explored, with a greater emphasis on the latter due to its drier and hotter summers (i.e., Hot-summer Mediterranean climate). Although the link between PSD and urban climatology is still maturing, the state-of-the-art is progressively gaining posture in its efforts to form local design guidelines when approaching local thermal comfort thresholds. In summary, and as a result of this article, the following outlooks are presented:

- There is still an over dependence on singular climatic variables that do not effectively assess local thermal comfort implications, both within top-down and bottom-up perspectives. More urgently, and with regards to bottom-up approaches, there still needs to be a better integration of thermo-physiological indices to help guide more wholesome bioclimatic evaluations of the public realm. Such a requisite is particularly pertinent in design projects that exclusively depend on variables such as Tamb to assess the current and prospective conditions as a result of PSD interventions.

- The existing divergence between qualitative and quantitative evaluations of thermal comfort conditions needs to be addressed further. Although thermal indices have incontestably proven their importance in approaching pedestrian thermo-physiological stress, it has also been proven that socio-psychological factors can also influence pedestrian interpretations of thermal stress. In other words, while human-biometeorological thresholds have been well documented (and in numerous ways), there is now the opportunity to further explore how simulations can potentially account for human qualitative criteria as well.