A Comparative Study of Pilot Reports and In Situ EDR Measurements of Aircraft Turbulence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

2.1. PIREPs

2.2. In Situ EDR Measurements

2.3. Event Matching

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Spatiotemporal Distribution Patterns

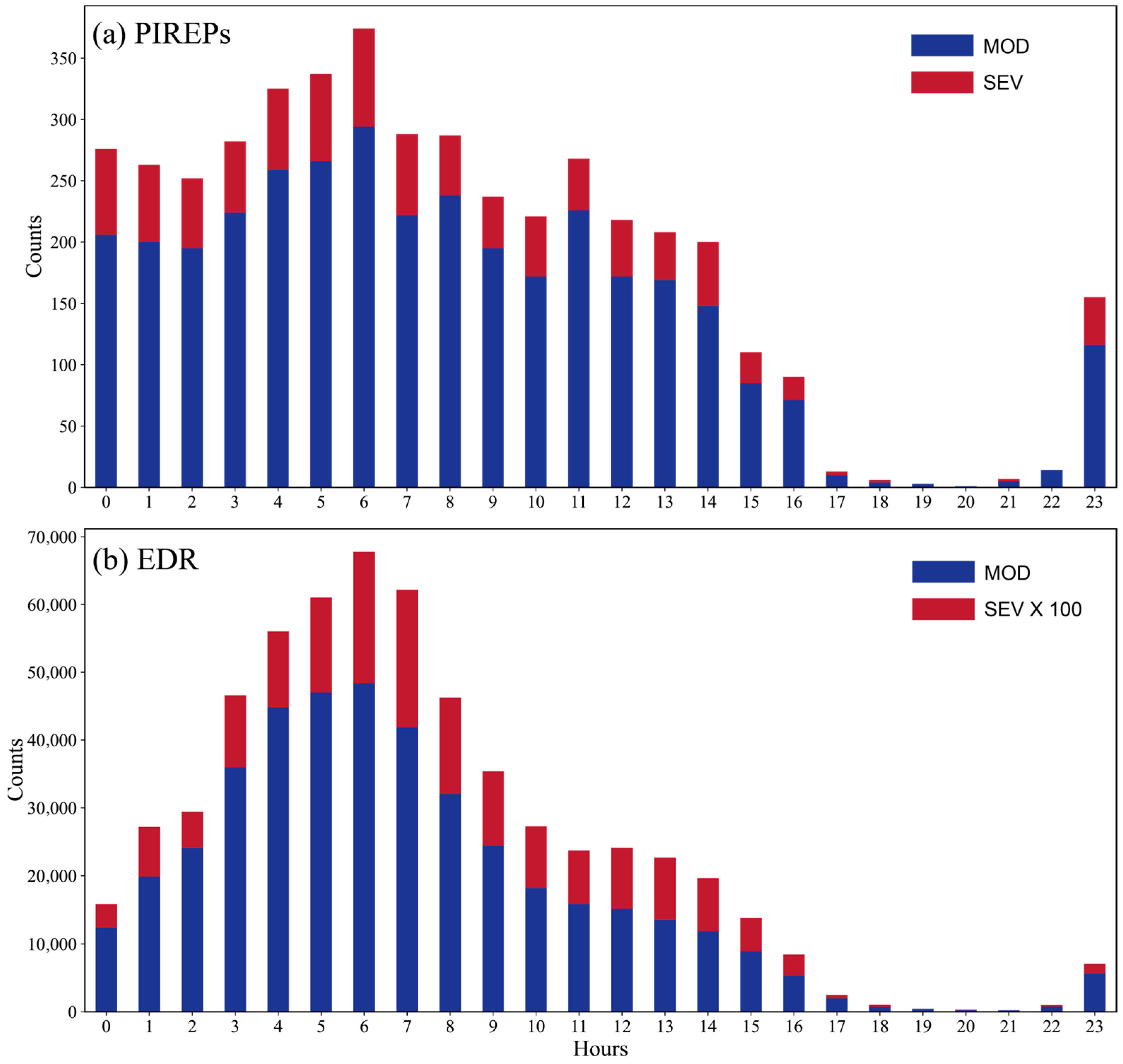

3.1.1. Temporal Distribution

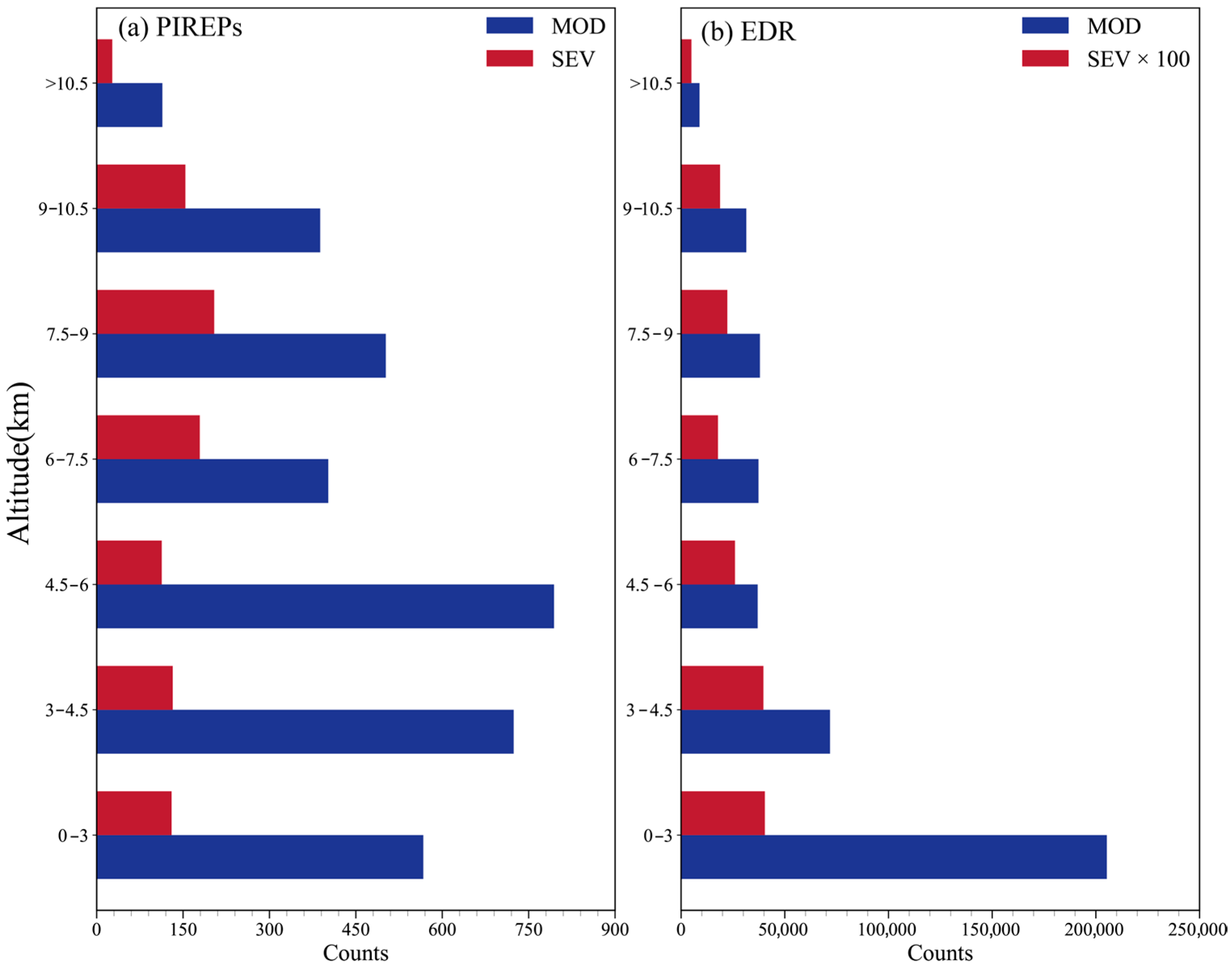

3.1.2. Altitude Distribution

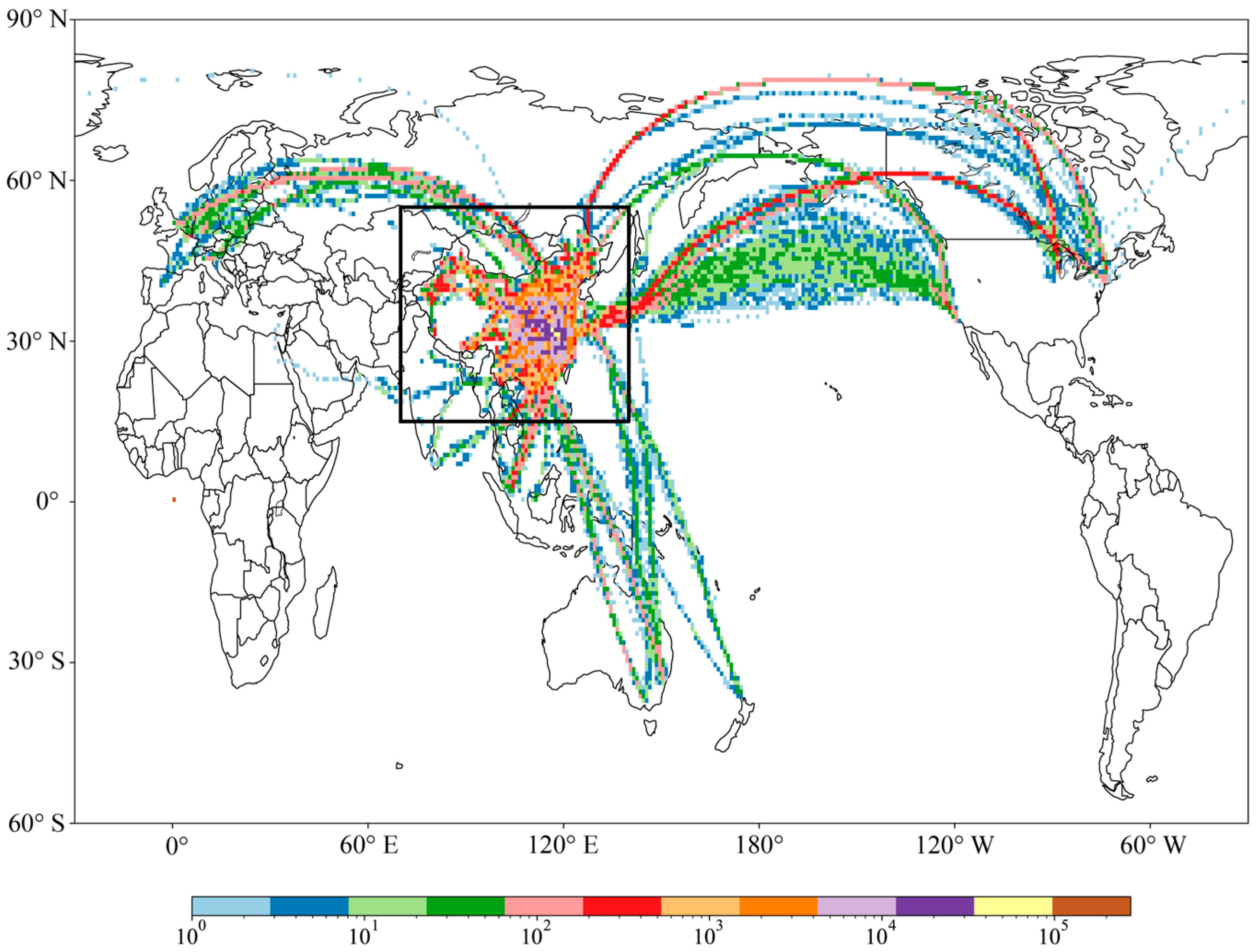

3.1.3. Spatial Distribution

3.2. Discrepancies from Matched Events

3.2.1. Spatiotemporal Discrepancy

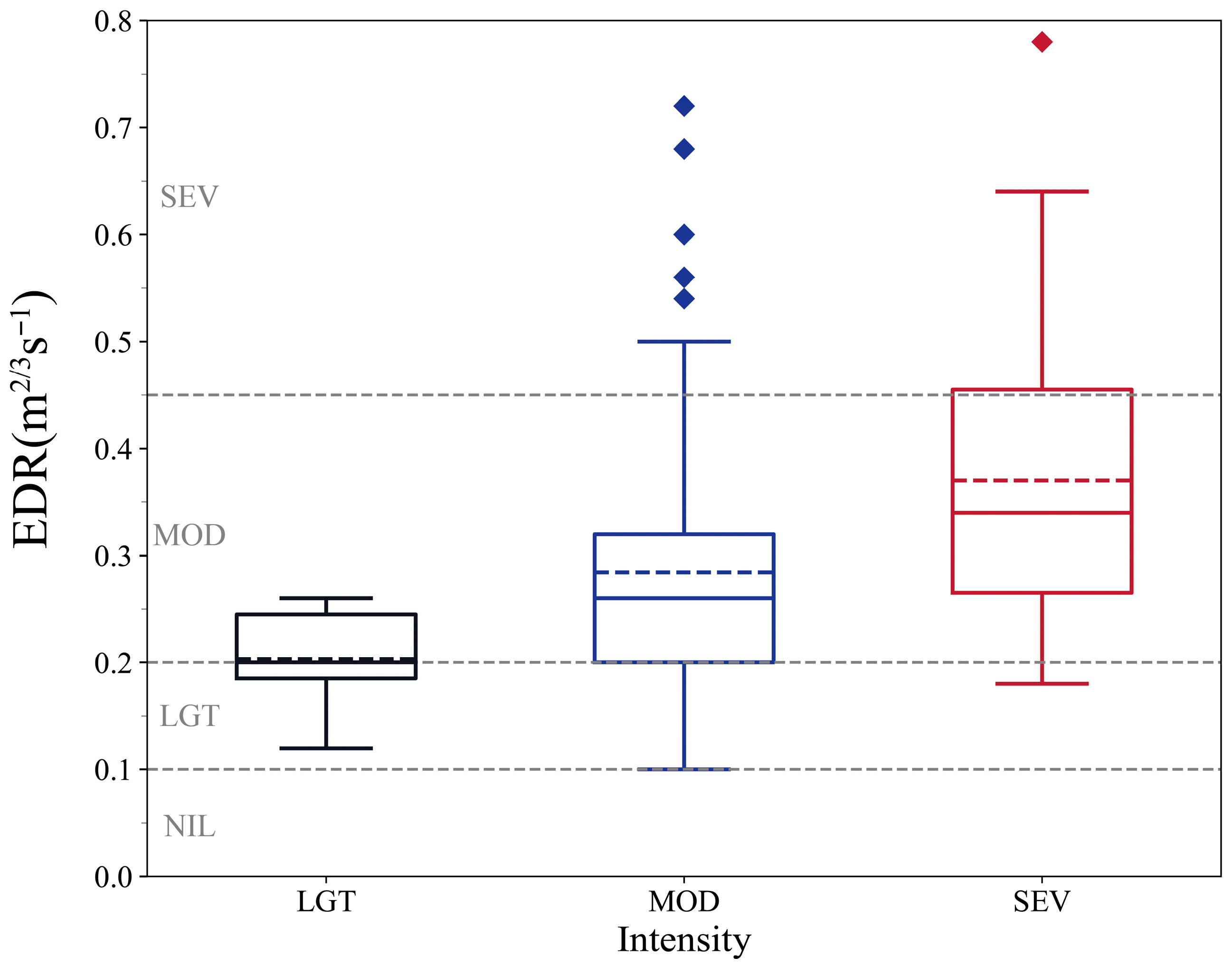

3.2.2. Intensity Discrepancy

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparative Advantages and Integration of PIREPs and EDR Data

4.2. Real-Time Data Transmission and Meteorological Application

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PIREPs | Pilot Reports |

| EDR | Eddy Dissipation Rate |

| NCAR | National Center for Atmospheric Research |

| ICAO | International Civil Aviation Organization |

| LGT | Light |

| LGT-MOD | Light-to-Moderate |

| MOD | Moderate |

| MOD-SEV | Moderate-to-Severe |

| SEV | Severe |

| NIL | Null |

| CEA | China Eastern Airlines |

| CAT | Clear-air Turbulence |

| QAR | Quick Access Recorder |

References

- Wolff, J.K.; Sharman, R.D. Climatology of Upper-Level Turbulence over the Contiguous United States. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2008, 47, 2198–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultepe, I.; Sharman, R.; Williams, P.D.; Zhou, B.; Ellrod, G.; Minnis, P.; Trier, S.; Griffin, S.; Yum, S.S.; Gharabaghi, B.; et al. A Review of High Impact Weather for Aviation Meteorology. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2019, 176, 1869–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, T.; Faranda, D.; Rapella, L.; Coppola, E.; Lepreti, F.; Dubrulle, B.; Carbone, V. Impacts of Changing Atmospheric Circulation Patterns on Aviation Turbulence over Europe. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2024GL111618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, M.C.; Williams, P.D.; Marlton, G.J.; Harrison, R.G. Evidence for Large Increases in Clear-Air Turbulence over the Past Four Decades. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2023GL103814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Sharman, R.D.; Kim, J.; Son, S.W. Climatology of Clear-Air Turbulence in Upper Troposphere and Lower Stratosphere in the Northern Hemisphere Using ERA5 Reanalysis Data. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2022, 128, e2022JD037679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.H.; Chun, H.Y.; Sharman, R.D. Global Response of Upper-Level Aviation Turbulence from Various Sources to Climate Change. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, J.; Han, Y.; Xu, H.; Guo, X.; Cao, L.; Gao, W. Increased Turbulence in the Eurasian Upper-Level Jet Stream in Winter: Past and Future. Earth Space Sci. 2021, 8, e2020EA001556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.D. Increased Light, Moderate, and Severe Clear-Air Turbulence in Response to Climate Change. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2017, 34, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.D.; Joshi, M.M. Intensification of Winter Transatlantic Aviation Turbulence in Response to Climate Change. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharman, R.; Tebaldi, C.; Wiener, G.; Wolff, J. An Integrated Approach to Mid-and Upper-Level Turbulence Forecasting. Wea. Forecast. 2006, 21, 268–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Chun, H.-Y.; Sharman, R.D.; Keller, T.L. Evaluations of Upper-Level Turbulence Diagnostics Performance Using the Graphical Turbulence Guidance (Gtg) System and Pilot Reports (PIREPs) over East Asia. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2011, 50, 1936–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Chen, X.; A, L.; Wu, K.; Liu, H.; Dai, F.; Yang, T.; Yu, J.; Wang, K. Analysis of the Relationship Between Upper-Level Aircraft Turbulence and the East Asian Westerly Jet Stream. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, T.P.; Sharman, R.D.; Trier, S.B.; Fovell, R.G.; Williams, J.K. Recent Advances in the Understanding of Near-Cloud Turbulence. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 2012, 93, 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, B. The Quantitative Use of PIREPs in Developing Aviation Weather Guidance Products. Wea. Forecast. 1996, 11, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Chen, D.; Gu, L. A Statistical Analysis of Aircraft Turbulence Pilot Reports in China in Past Decade. J. Civ. Aviat. Flight 2021, 32, 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Meymaris, G.; Sharman, R.D.; Cornman, L.; Deierling, W. The NCAR In Situ Turbulence Detection Algorithm; NCAR TN-560 + EDD Deierling; National Science Foundation: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cornman, L.B.; Morse, C.S.; Cunning, G. Real-Time Estimation of Atmospheric Turbulence Severity from in-Situ Aircraft Measurements. J. Aircr. 1995, 32, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornman, L.B.; Meymaris, G.; Limber, M. An Update on the FAA Aviation Weather Research Program’s In Situ Turbulence Measurement and Reporting System. In Proceedings of the 11th AMS Conference on Aviation, Range, and Aerospace Meteorology, Hyannis, MA, USA, 4–8 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sharman, R.D.; Cornman, L.B.; Meymaris, G.; Pearson, J.; Farrar, T. Description and Derived Climatologies of Automated In Situ Eddy-Dissipation-Rate Reports of Atmospheric Turbulence. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2014, 53, 1416–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Civil Aviation Organization. Annex 3—Meteorological Service for International Air Navigation; International Civil Aviation Organization: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sharman, R.D.; Pearson, J.M. Prediction of Energy Dissipation Rates for Aviation Turbulence. Part I: Forecasting Nonconvective Turbulence. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2017, 56, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Sharman, R.; Strahan, M.; Scheck, J.W.; Bartholomew, C.; Cheung, J.C.H.; Buchanan, P.; Gait, N. Improvements in Nonconvective Aviation Turbulence Prediction for the World Area Forecast System. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 2018, 99, 2295–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-B.; Chun, H.-Y.; Kim, J.-H. Evaluation of Multimodel-Based Ensemble Forecasts for Clear-Air Turbulence. Wea. Forecast. 2019, 35, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.C.; Chun, H.Y.; Sharman, R.D.; Kim, J.H. Comparison of Eddy Dissipation Rate Estimated from Operational Radiosonde and Commercial Aircraft Observations in the United States. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2023, 128, e2023JD039352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Ding, J.; Liu, G.; Tang, J. Objective Verification of Clear-Air Turbulence (CAT) Diagnostic Performance in China Using In Situ Aircraft Observation. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2022, 39, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Wan, Z.; Wu, W.; Yang, B.; Yi, Z. An Ensemble Prediction Method of Aviation Turbulence Based on the Energy Dissipation Rate. Chin. J. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 47, 1085–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eick, D.E. Ntsb Recommendations to Prevent Turbulence-Related Injuries in Air Carrier Operations. In Proceedings of the 102nd Annual AMS Meeting 2022, Houston, TX, USA, 1 January 2022; p. 314. [Google Scholar]

- Liman, A.; Wang, J.; Feng, J. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of High Altitude Turbulence over Eastern China and Their Relationship with the Equatorial Central and Eastern Pacific Sea Surface Temperature. Chin. J. Atmos. Sci. 2016, 40, 1073–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Zhuang, Z.; Yu, Z.; Lin, K.; Wu, K.; Leung, Y.Y.; Chan, P.W. The Prospective Application of Machine Learning in Turbulence Forecasting over China. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2024, 63, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wu, K.; Liu, H.; Xu, W.; Li, G.; Yang, Z.; Liu, G.; Duan, B. Spatiotemporal Distribution Patterns of Turbulence on Major High-Altitude Aircraft Routes in China. Trans. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 47, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharman, R.D.; Trier, S.B. Influences of Gravity Waves on Convectively Induced Turbulence (Cit): A Review. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2018, 176, 1923–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, E. Clear Air Turbulence and Civil Jet Operations. Aeronaut. J. 1955, 59, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharman, R.; Lane, T. (Eds.) Aviation Turbulence: Processes, Detection, Prediction; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ellrod, G.P.; Knapp, D.I. An Objective Clear-Air Turbulence Forecasting Technique: Verification and Operational Use. Wea. Forecast. 1992, 7, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.A.; Panofsky, H.A. Clear Air Turbulence: A Mystery May Be Unfolding. Science 1970, 167, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Transportation Safety Board. Preventing Turbulence-Related Injuries in Air Carrier Operations Conducted Under Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 121; National Transportation Safety Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- International Civil Aviation Organization. Proposed Revision to Eddy Dissipation Rate (EDR) Values in Annex 3; International Civil Aviation Organization: Exeter, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-H.; Chun, H.-Y.; Chan, P.W. Comparison of Turbulence Indicators Obtained from In Situ Flight Data. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2017, 56, 1609–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.; Lin, K.; Zhang, H.; Chan, P.-W. Detection of Turbulence Anomalies Using a Symbolic Classifier Algorithm in Airborne Quick Access Record (QAR) Data Analysis. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 41, 1438–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matti, E.; Johns, O.; Khan, S.; Gurtov, A.; Josefsson, B. Aviation Scenarios for 5G and Beyond. In Proceedings of the 2020 AIAA/IEEE 39th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), San Antonio, TX, USA, 11–15 October 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, J.M.; Sharman, R.D. Prediction of Energy Dissipation Rates for Aviation Turbulence. Part II: Nowcasting Convective and Nonconvective Turbulence. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2017, 56, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-S.; Chun, H.-Y. Machine Learning Application and Operational Strategy for Global Low-Level Aviation Turbulence Forecasting. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civil Aviation Administration of China. China’s New Generation Aviation Broadband Communication Technology Roadmap; Civil Aviation Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

| Data Source | NIL | LGT | MOD | SEV | TOTAL |

| PIREPs | 0 | 118 | 3495 | 940 | 4553 |

| EDR | 4,561,154 | 1,623,383 | 430,030 | 1701 | 6,616,268 |

| Intensity | No. of Samples | 25th Percentile | Median | 75th Percentile | Avg | |

| LGT | 6 | Distance (km) | 13.16 | 21.71 | 27.04 | 22.46 |

| Time (s) | −45.00 | 0.00 | 45.00 | −20.00 | ||

| Vertical displacement (ft) | −58.78 | −23.78 | −12.23 | −44.23 | ||

| EDR value | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.20 | ||

| MOD | 190 | Distance (km) | 14.12 | 24.06 | 34.10 | 24.66 |

| Time (s) | −240.00 | −120.00 | 0.00 | −139.89 | ||

| Vertical displacement (ft) | −291.54 | −32.17 | 114.47 | −29.13 | ||

| EDR value | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.28 | ||

| SEV | 46 | Distance (km) | 16.84 | 26.72 | 38.62 | 28.94 |

| Time (s) | −240.00 | −180.00 | 0.00 | −166.96 | ||

| Vertical displacement (ft) | −592.46 | −67.14 | 439.75 | −56.09 | ||

| EDR value | 0.28 | 0.34 | 0.46 | 0.37 | ||

| TOTAL | 242 | Distance (km) | 14.80 | 24.82 | 34.94 | 25.42 |

| Time (s) | −240.00 | −120.00 | 0.00 | −142.07 | ||

| Vertical displacement (ft) | −327.28 | −33.78 | 142.81 | −34.63 | ||

| EDR value | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shao, J.; Li, Y.; Leung, Y.Y.; Yu, Z.; Wu, K.; Gu, W.; Bai, Y.; Chan, P.-W.; Zhuang, Z. A Comparative Study of Pilot Reports and In Situ EDR Measurements of Aircraft Turbulence. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121414

Shao J, Li Y, Leung YY, Yu Z, Wu K, Gu W, Bai Y, Chan P-W, Zhuang Z. A Comparative Study of Pilot Reports and In Situ EDR Measurements of Aircraft Turbulence. Atmosphere. 2025; 16(12):1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121414

Chicago/Turabian StyleShao, Jingyuan, Yi Li, Yan Yu Leung, Zhenyu Yu, Kaijun Wu, Wenhan Gu, Yiqin Bai, Pak-Wai Chan, and Zibo Zhuang. 2025. "A Comparative Study of Pilot Reports and In Situ EDR Measurements of Aircraft Turbulence" Atmosphere 16, no. 12: 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121414

APA StyleShao, J., Li, Y., Leung, Y. Y., Yu, Z., Wu, K., Gu, W., Bai, Y., Chan, P.-W., & Zhuang, Z. (2025). A Comparative Study of Pilot Reports and In Situ EDR Measurements of Aircraft Turbulence. Atmosphere, 16(12), 1414. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121414