Characteristics and Driving Factors of PM2.5 Concentration Changes in Central China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Observation Data

2.2. Statistical Modeling Framework

2.2.1. Rationale for Model Selection

2.2.2. Random Forest Implementation

2.2.3. Multiple Linear Regression Protocol

2.3. Chemical Transport Modeling

2.3.1. WRF-CMAQ Configuration

2.3.2. Emission Inventory Processing

2.3.3. Sensitivity Experiment Design

3. Results and Discussion

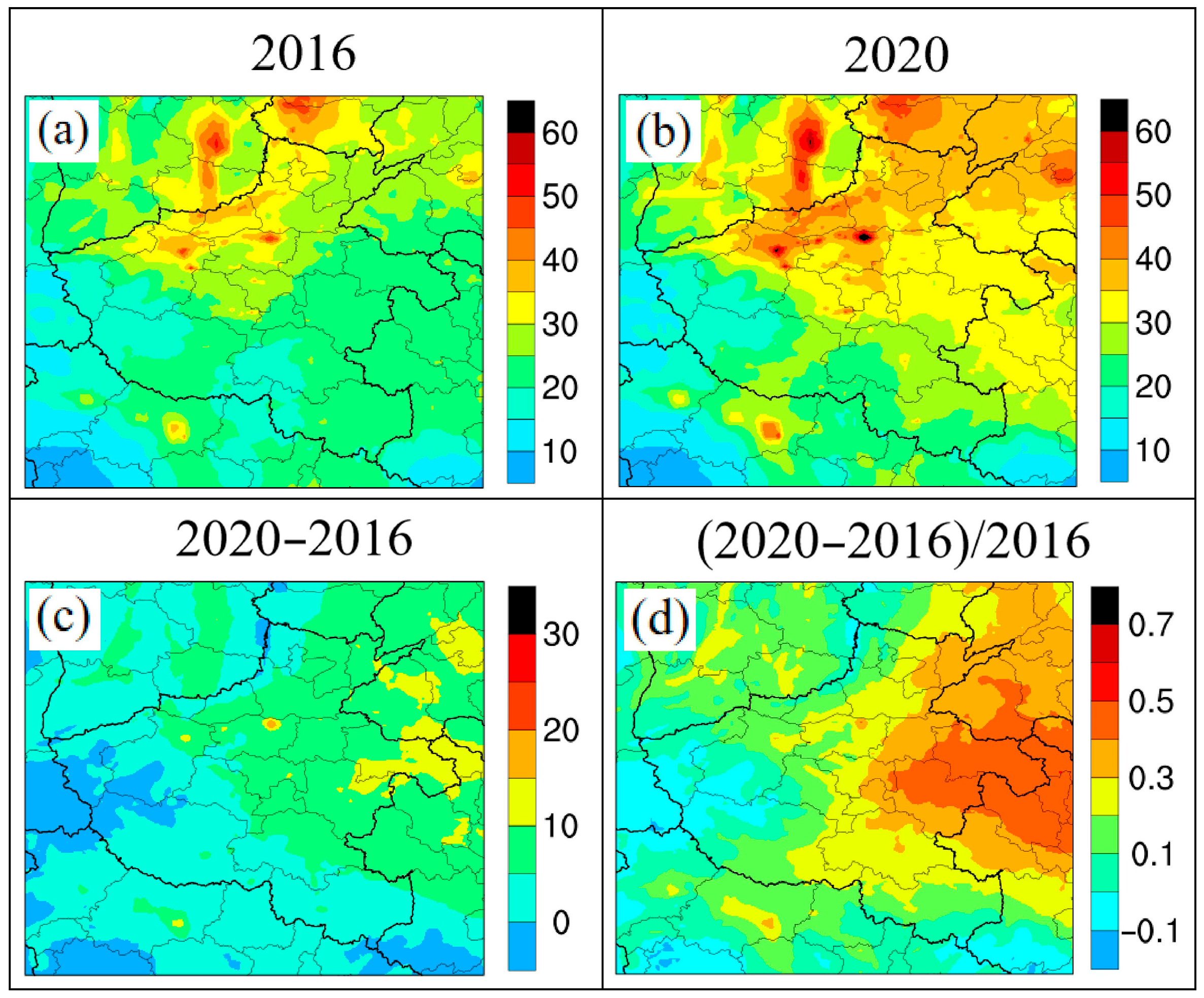

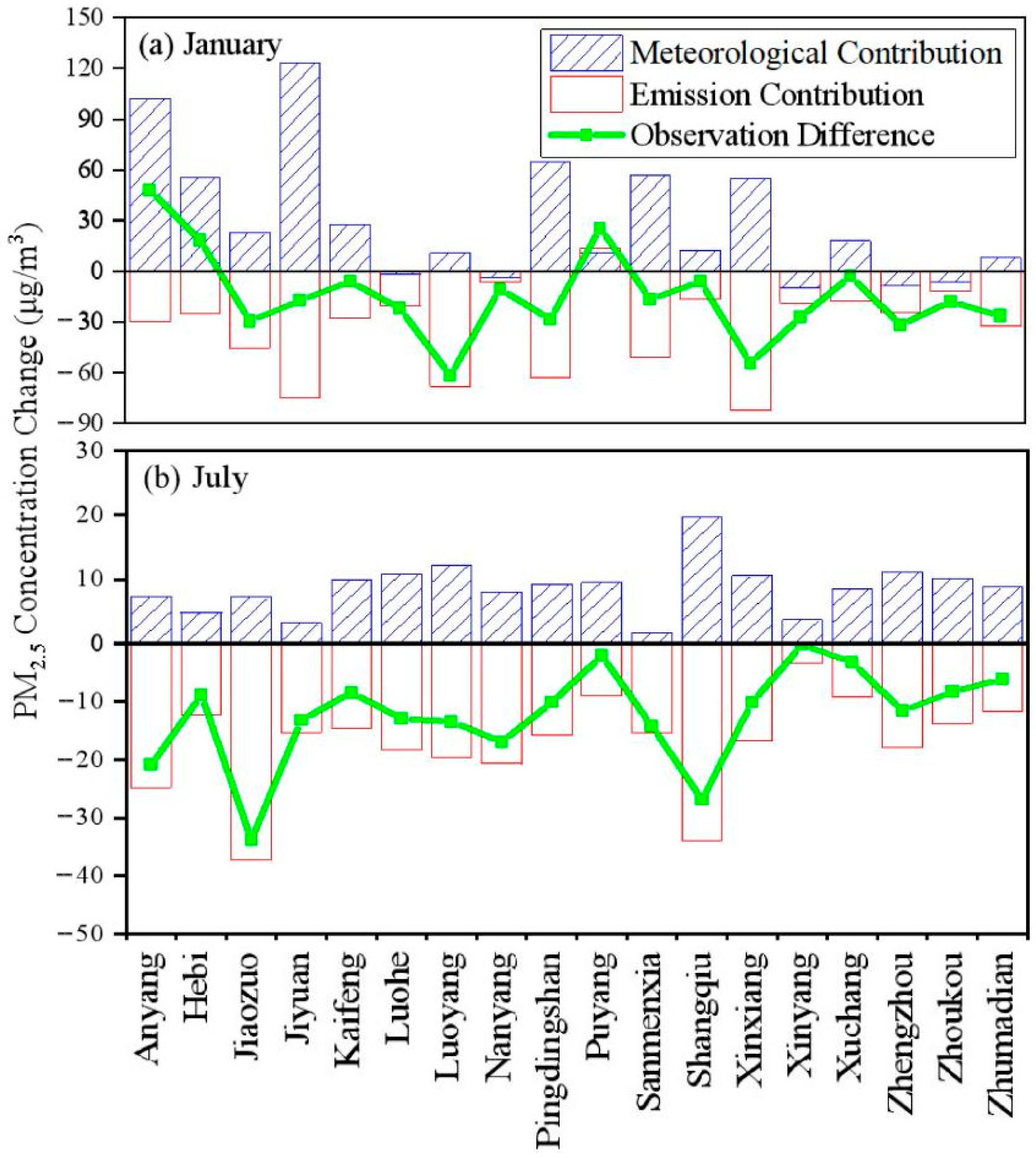

3.1. Emission Separation Contribution Based on Random Forest Method

3.2. Meteorological and Pollution Characteristics of the Reference Year

3.3. Impact of Meteorological Conditions

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, S.; Gao, D.; Liao, F.; Zhou, F.; Wang, X. The health effects of ambient PM2.5 and potential mechanisms. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 128, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbari, K.; Sicard, P.; Khaniabadi, Y.-O.; Naqvi, H.-R.; Fard, R.F.; Rashidiet, R. PM2.5 and PM10-related carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risk assessment in Iran. J. Atmos. Chem. 2024, 81, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaniabadi, Y.O.; Sicard, P.; Dehghan, B.; Mousavi, H.; Saeidimehr, S.; Farsani, M.H.; Monfared, S.M.; Maleki, H.; Moghadam, H.; Birgani, P.M. COVID-19 Outbreak Related to PM10, PM2.5, Air Temperature and Relative Humidity in Ahvaz, Iran. Dr. Sulaiman Al Habib Med. J. 2022, 4, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Dai, C.; Wei, Y.; Ren, H.; Zhou, J. Air pollution prevention and control action plan substantially reduced PM2.5 concentration in China. Energy Econ. 2022, 113, 106206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, G.; Fu, W. Government environmental governance, structural adjustment and air quality: A quasi-natural experiment based on the Three-year Action Plan to Win the Blue Sky Defense War. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 277, 111470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSouza, P.; Lu, R.; Kinney, P.; Zheng, S. Exposures to multiple air pollutants while commuting: Evidence from Zhengzhou, China. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 247, 118168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wei, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Jiang, N.; Wu, F. Characteristics and sources of PM2.5 in diverse central China cities under various scenarios: Maximum simulated emission reduction based on long-term data. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 491, 138022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikhovtsev, M.Y.; Obolkin, V.A.; Khodzher, T.V.; Molozhnikova, V.Y. Variability of the Ground Concentration of Particulate Matter PM1–PM10 in the Air Basin of the Southern Baikal Region. Atmos. Ocean Opt. 2023, 36, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.; Hao, J. Simulating aerosol–radiation–cloud feedbacks on meteorology and air quality over eastern China under severe haze conditionsin winter. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 2387–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Tong, D.; Li, M.; Liu, F.; Hong, C.; Geng, G.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Peng, L.; Qi, J.; et al. Trends in China’s anthropogenic emissions since 2010 as the consequence of clean air actions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 14095–14111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, N.; Huang, Z.; Shi, B.; Yuan, X.; Sheng, L.; Zhang, A.; You, Y.; Chen, D.; et al. Contribution of anthropogenic emission changes to the evolution of PM2.5 concentrations and composition in the Pearl River Delta during the period of 2006–2020. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 318, 120228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Liu, P.; Song, H.; Yang, D.; Yang, J.; Song, G.; Yang, D.; Yang, J.; Song, G.; Miao, C.; et al. Effects of anthropogenic precursor emissions and meteorological conditions on PM2.5 concentrations over the “2+26” cities of northern China. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 315, 120392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Xu, C.; Wan, Z.; Cao, M.; Xu, K.; Chen, N. Reduction potential of ammonia emissions and impact on PM2.5 in a megacity of central China. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 343, 123172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, B.; Xu, W.; Wang, F.; Gao, J.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Feng, Y.; Shi, G. Machine learning combined with the PMF model reveal the synergistic effects of sources and meteorological factors on PM2.5 pollution. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.; Jacob, D.J.; Wang, X.; Shen, L.; Li, K.; Zhang, Y.; Gui, K.; Zhao, T.; Liao, H. Fine particulate matter PM2.5 trends in China, 2013–2018: Separating contributions from anthropogenic emissions and meteorology. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 11031–11041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liao, H.; Lou, S. Increase in winter haze over eastern China in recent decades: Roles of variations in meteorological parameters and anthropogenic emissions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2016, 121, 13050–13065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, K.; Che, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, Y.; Sun, T.; Zhang, X. Satellite-derived PM2.5 concentration trends over Eastern China from 1998 to 2016: Relationships to emissions and meteorological parameters. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 247, 1125–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Lv, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Yan, X.; Sun, Y.; Cribb, M. Aerosol hygroscopic growth, contributing factors, and impact on haze events in a severely polluted region in northern China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 1327–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Wang, S.; Xing, J.; Chang, X.; Ding, D.; Zheng, H. Regional transport in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region and its changes during 2014–2017: The impacts of meteorology and emission reduction. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 139792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Li, J.; Li, A.; Xie, P.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. Modeling study of surface PM2.5 and its source apportionment over Henan in 2013–2014. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2016, 36, 3543–3553. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, D.M.; Tai, A.P.; Mickley, L.J.; Moch, J.M.; Van, D.A.; Shen, L.; Martin, R.V. Synoptic meteorological modes of variability for fine particulate matter (PM2.5) air quality in major metropolitan regions of China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 6733–6748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yao, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Ji, D.; Tang, G.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Hu, B.; Xin, J. Mechanism for the formation of the January 2013 heavy haze pollution episode over central and eastern China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2014, 57, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, A.P.K.; Mickley, L.J.; Jacob, D.J.; Leibensperger, E.M.; Zhang, L.; Fisher, J.A.; Pye, H.O.T. Meteorological modes of variability for fine particulate matter (PM2.5) air quality in the United States: Implications for PM2.5 sensitivity to climate change. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 3131–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Koo, J.H. Arctic sea ice, Eurasia snow, and extreme winter haze in China. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1602751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Mickley, L.J.; Murray, L.T. Influence of 2000–2050 climate change on particulate matter in the United States: Results from a new statistical model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 4355–4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.V.; Shi, Z.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, Q.; He, K.; Wang, S.; Harrison, R.M. Assessing the impact of clean air action on air quality trends in Beijing using a machine learning technique. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 11303–11314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.V.; Shi, Z.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, Q.; He, K.; Wang, S.; Harrison, R.M. Abrupt but smaller than expected changes in surface air quality attributable to COVID-19 lockdowns. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Vu, T.V.; Sun, J.; He, J.; Shen, X.; Lin, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, J.; Gao, W.; Wang, Y.; et al. Significant changes in chemistry of fine particles in wintertime Beijing from 2007 to 2017: Impact of clean air actions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 1344–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and regression by random Forest. R News 2002, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Immitzer, M.; Atzberger, C.; Koukal, T. Tree species classification with random forest using very high spatial resolution 8-band WorldView-2 satellite data. Remote Sens. 2012, 4, 2661–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Tian, H.; Luo, L.; Liu, S.; Bai, X.; Zhao, H.; Lin, S.; Zhao, S.; Guo, Z.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Meteorology-normalized variations of air quality during the COVID-19 lockdown in three Chinese megacities. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2022, 13, 101452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Tian, H.; Luo, L.; Liu, S.; Bai, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, K.; Lin, S.; Zhao, S.; Guo, Z.; et al. Understanding and revealing the intrinsic impacts of the COVID-19 lockdown on air quality and public health in North China using machine learning. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, N.R.; Smith, H. Applied Regression Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kalnay, E.; Kanamitsu, M.; Kistler, R.; Collins, W.; Deaven, D.; Gandin, L.; Iredell, M.; Saha, S.; White, G.; Woollen, J.; et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. In Renewable Energy; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. Vol1_146–Vol1_194. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, L.; Lu, X.; Yin, S.; Zhang, H.; Ma, S.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R. A recent emission inventory of multiple air pollutant, PM2.5 chemical species and its spatial-temporal characteristics in central China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 269, 122114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, A.B.; Jiang, X.; Heald, C.L.; Sakulyanontvittaya, T.; Duhl, T.A.; Emmons, L.K.; Wang, X. The Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature version 2.1 (MEGAN2.1): An extended and updated framework for modeling biogenic emissions. Geosci. Model Dev. 2012, 5, 1471–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa, J.; Ohara, T.; Morikawa, T.; Hanayama, S.; Janssens-Maenhout, G.; Fukui, T.; Kawashima, K.; Akimoyo, H. Emissions of air pollutants and greenhouse gases over Asian regions during 2000–2008: Regional Emission inventory in ASia (REAS) version 2. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 11019–11058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, X. Causes and Transmission Characteristics of the Regional PM2.5 Heavy Pollution Process in the Urban Agglomerations of the Central Taihang Mountains. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Yang, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z. Quantifying the Source Contributions to Poor Atmospheric Visibility in Winter over the Central Plains Economic Region in China. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S.; Liu, M.; Chen, B.; Huang, Y.; Wang, M.; Ma, Q.; Han, Y. Analysis of the PM2.5–O3 Pollution Characteristics and Its Potential Sources in Major Cities in the Central Plains Urban Agglomeration from 2014 to 2020. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudan, J.; Banzhaf, S.; Khan, B.; Nagel, K. Air Quality-Driven Traffic Management Using High-Resolution Urban Climate Modeling Coupled with a Large Traffic Simulation. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.P. Air Pollution Meteorology and Dispersion; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Akimoto, H. Global air quality and pollution. Science 2003, 302, 1716–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lau, A.; Wong, A.; Fung, J. Decomposition of the wind and nonwind effects on observed year-to-year air quality variation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2014, 119, 6207–6220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, L. Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics of PM2.5 Pollution and the Influential Meteorological Factors in the Henan Province, China, 2021. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 32, 5211–5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, P.; Zhang, G.; Kong, F.; Chen, D.; Azorin-Molina, C.; Guijarro, J.A. Variability of winter haze over the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region tied to wind speed in the lower troposphere and particulate sources. Atmos. Res. 2019, 215, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Mao, H.; Gong, S.; Yu, Y.; Wu, L.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Jing, B.; Ren, P.; Zou, C. Investigation of particulate matter regional transport in Beijing based on numerical simulation. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2017, 17, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dickinson, R.E.; Su, L.; Zhou, C.; Wang, K. PM2.5 pollution in China and how it has been exacerbated by terrain and meteorological conditions. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2018, 99, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Xu, J.; Tie, X.; Wu, J. Impact of the 2015 El Nino event on winter air quality in China. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.; Wooldridge, P.J.; Gilman, J.B.; Warneke, C.; De, G.J.; Cohen, R.C. Low temperatures enhance organic nitrate formation: Evidence from observations in the 2012 Uintah Basin Winter Ozone Study. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 14, 12441–12454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Xu, J.; Yue, W.; Mao, W.; Yang, D.; Wang, J. Response of PM2.5 pollution to land use in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Month | RMSE | R2 | MFB | MFE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 15.04 | 0.79 | −0.03 | 0.18 |

| July | 5.53 | 0.72 | −0.14 | 0.25 |

| December | 8.74 | 0.82 | −0.23 | 0.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Y.; Wang, K.; Liu, X.; Xu, Q.; Luo, L.; Liu, P.; He, Y.; Yu, Y.; Su, F.; Zhang, R. Characteristics and Driving Factors of PM2.5 Concentration Changes in Central China. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1227. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16111227

Zhao Y, Wang K, Liu X, Xu Q, Luo L, Liu P, He Y, Yu Y, Su F, Zhang R. Characteristics and Driving Factors of PM2.5 Concentration Changes in Central China. Atmosphere. 2025; 16(11):1227. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16111227

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Yue, Ke Wang, Xiaoyong Liu, Qixiang Xu, Le Luo, Panpan Liu, Yanhua He, Yan Yu, Fangcheng Su, and Ruiqin Zhang. 2025. "Characteristics and Driving Factors of PM2.5 Concentration Changes in Central China" Atmosphere 16, no. 11: 1227. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16111227

APA StyleZhao, Y., Wang, K., Liu, X., Xu, Q., Luo, L., Liu, P., He, Y., Yu, Y., Su, F., & Zhang, R. (2025). Characteristics and Driving Factors of PM2.5 Concentration Changes in Central China. Atmosphere, 16(11), 1227. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16111227