Research on the Mechanism of the Influence of Thermal Stress on Tourists’ Environmental Responsibility Behavior Intention: An Example from a Desert Climate Region, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

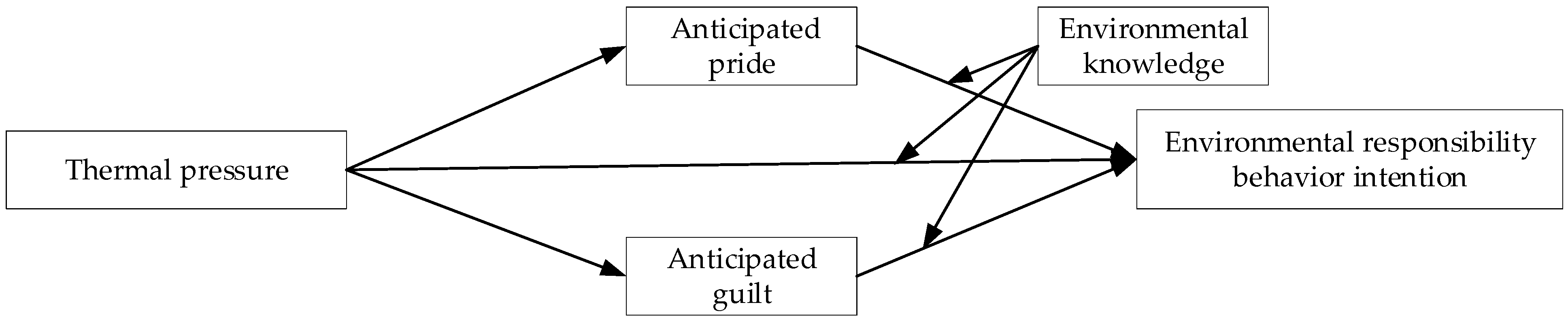

2. Literature Review

2.1. Thermal Stress

2.2. Anticipated Emotions

2.3. Environmental Responsibility Behavior Intention (ERBI)

2.4. Environmental Knowledge

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. The Relationship between Thermal Stress and ERBI

3.2. The Relationship between Thermal Stress and Anticipated Emotions

3.3. The Relationship between Anticipated Emotions and ERBI

3.4. The Mediating Effect of Anticipated Emotions

3.5. The Moderating Effect of Environmental Knowledge

4. Research Design

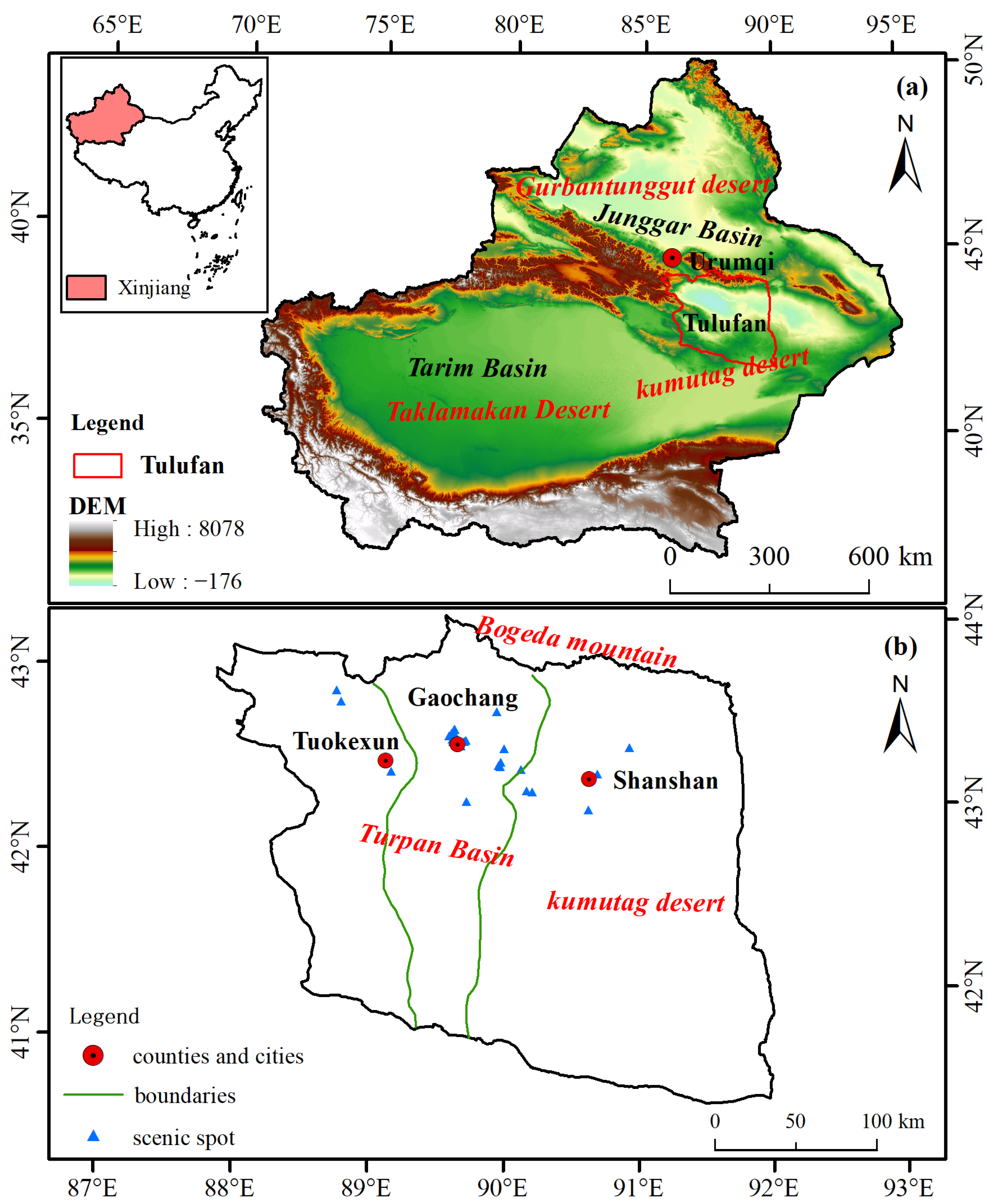

4.1. Study Area

4.2. Questionnaire Design

4.3. Variable Measurement

4.4. Data Collection

5. Results

5.1. Common Method Variance Test

5.2. Reliability and Validity Testing

5.3. Hypothesis Testing

5.4. Mediation Effect Testing

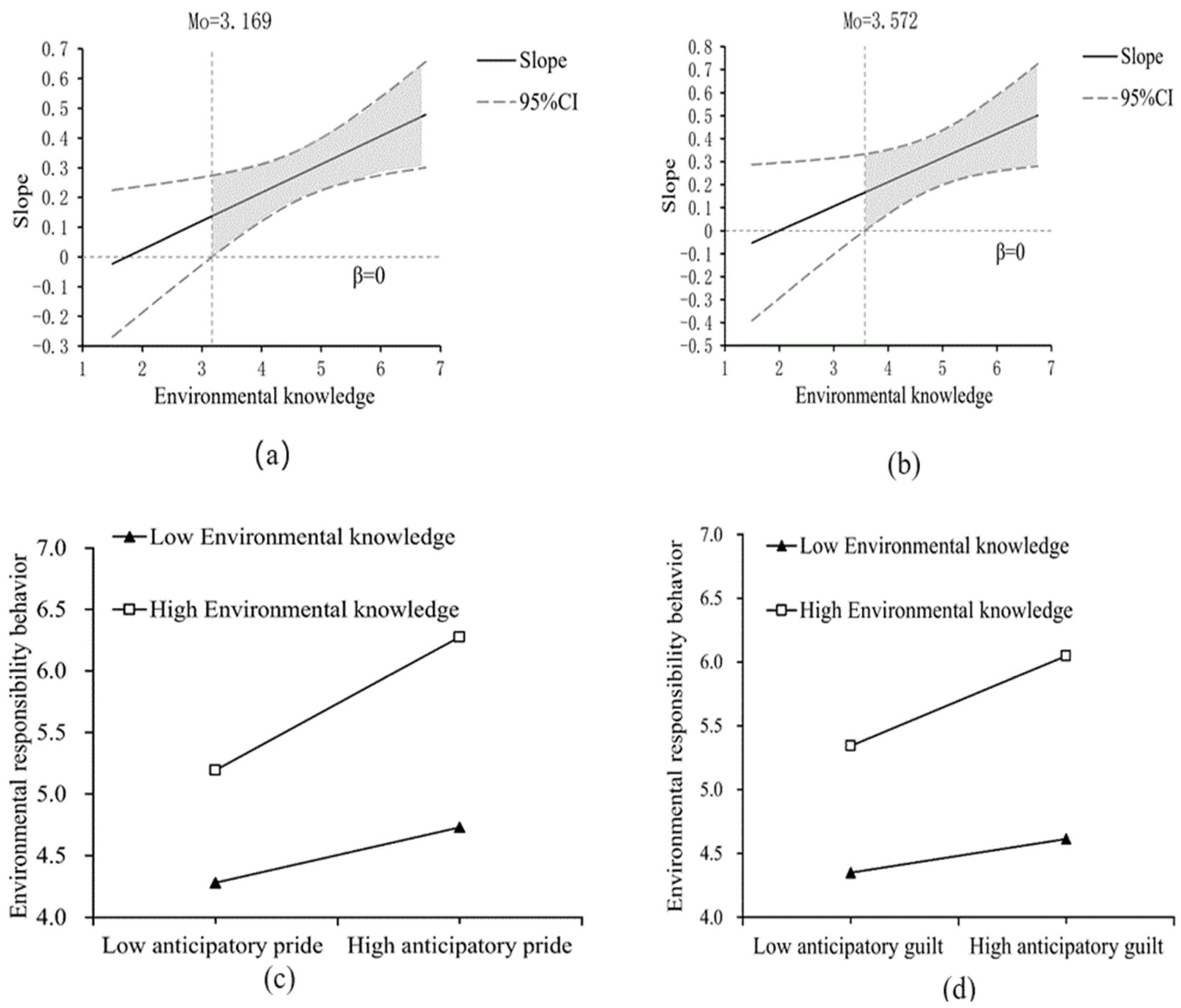

5.5. Test for Moderation Effect

5.6. Testing the Moderated Mediation Effect

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Management Insights

6.3. Research Limitations

6.4. Future Prospects

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hua, Y.; Dong, F. Can environmental responsibility bridge the intention-behavior gap? Conditional process model based on valence theory and the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 376, 134166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Wall, G.; McBoyle, G. Climate change and tourism and recreation in north America: Exploring regional risks and opportunities. In Tourism, Recreation and Climate Change; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2005; pp. 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D. Climate Change Implications for Tourism. In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Tourism; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, E.; Dolnicar, S.; Grün, B. Understanding how a commitment-based pledge intervention encourages pro-environmental tourist behaviour. Tour. Manag. 2024, 104, 104928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, S. Difference in Thermal Comfort at the Province Scale: A Case Study of the Nanshan Cultural Tourism Zone. Trop. Geogr. 2023, 40, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y. Influence of Tourism Experience on Environmental Attitude and Behavior: A Longitudinal Tracking Study. J. Nat. Resour. 2018, 33, 1642–1656. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, J.; Liu, J. Tourists’environmentally responsible behavior intentions based on embodied perceptions: The arousal of awe and anticipated self-conscious emotions. Tour. Trib. 2022, 37, 80–95. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J.; Li, C.; Liu, C. A Study of Enterprises’ Investment Behavioron Environmental Protection Based on Corporate Governance. J. Zhengzhou Univ. 2017, 50, 60–65+159. [Google Scholar]

- Lavuri, R.; Roubaud, D.; Grebinevych, O. Sustainable consumption behaviour: Mediating role of pro-environment self-identity, attitude, and moderation role of environmental protection emotion. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 347, 119106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, X.; Tse, S.; Wang, L. Connecting Environmental Perception, Awe, Face Consciousness, and Environmentally Responsible Behaviors: A Mediated-Moderated Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, S.; Yao, J. The Impact of Different Value Types on Environmentally Responsible Behavior: An Empirical Study from Residents of National Park Communities in China. Land 2024, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.M.; Nguyen, Y. Do Perceptions of Destination Social Responsibility Contribute to Environmentally Responsible Behavior? A Case Study in Phu Quoc, Vietnam. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-W.; Tsao, H.-C. Exploring First-Time and Repeat Volunteer Scuba Divers’ Environmentally Responsible Behaviors Based on the C-A-B Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Zhang, T. Authenticity and Quality of Industrial Heritage as the Drivers of Tourists’ Loyalty and Environmentally Responsible Behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A. Visitors’ Environmental Conservation Behaviour in the Mountain Tourism Destinations in Pakistan. Rev. Appl. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2024, 7, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bröde, P.; Fiala, D.; Kampmann, B. Application of Statistical Learning Algorithms in Thermal Stress Assessment in Comparison with the Expert Judgment Inherent to the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI). Atmosphere 2024, 15, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieczkowski, Z. The tourism climatic index: A method of evaluating world climates for tourism. Can. Geogr./Géographies Can. 1985, 29, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazejczyk, K.; Epstein, Y.; Jendritzky, G.; Staiger, H.; Tinz, B. Comparison of UTCI to selected thermal indices. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2012, 56, 515–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Jiménez, J.L.; Ruiz de Adana, M. Assessment of Outdoor Thermal Comfort in a Hot Summer Region of Europe. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.; Davtalab, J.; Sargazi, M.A. Effect of awning on thermal comfort adjustment in open urban space using PET and UTCI indexes: A case study of Sistan region in Iran. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binarti, F.; Koerniawan, M.D.; Triyadi, S.; Utami, S.S.; Matzarakis, A. A review of outdoor thermal comfort indices and neutral ranges for hot-humid regions. Urban Clim. 2020, 31, 100531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, B.; Chen, H. Research Review and Evaluation Framework of Outdoor Thermal Comfort. Build. Sci. 2023, 36, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Gopinath, M.; Nyer, P.U. The role of emotions in marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. Self-conscious emotions: Embarrassment, pride, shame, guilt, and hubris. Handb. Emot. 2016, 4, 792–814. [Google Scholar]

- Harth, N.S.; Leach, C.W.; Kessler, T. Guilt, anger, and pride about in-group environmental behaviour: Different emotions predict distinct intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, J.L.; Robins, R.W. The psychological structure of pride: A tale of two facets. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Stillwell, A.M.; Heatherton, T.F. Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 115, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracy, J.L.; Robins, R.W. Putting the Self Into Self-Conscious Emotions: A Theoretical Model. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H. How recreation involvement, place attachment and conservation commitment affect environmentally responsible behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryxell, G.E.; Lo, C.W. The influence of environmental knowledge and values on managerial behaviours on behalf of the environment: An empirical examination of managers in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 46, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Merrilees, B.; Coghlan, A. Sustainable urban tourism: Understanding and developing visitor pro-environmental behaviours. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Guo, Y.; Han, X. The relationship research between restorative perception, local attachment and environmental responsible behavior of urban park recreationists. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arco, M.; Marino, V.; Resciniti, R. Exploring the pro-environmental behavioral intention of Generation Z in the tourism context: The role of injunctive social norms and personal norms. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkowski, T.J. An Analysis of Correlates and Predictors of Responsible Environmental Behavior; Southern Illinois University at Carbondale: Carbondale, IL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Schahn, J.; Holzer, E. Studies of individual environmental concern: The role of knowledge, gender, and background variables. Environ. Behav. 1990, 22, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-S.; Shih, L.-H. Effective environmental management through environmental knowledge management. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 6, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Zelezny, L. Values as predictors of environmental attitudes: Evidence for consistency across 14 countries. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Xiong, Y. A Research Summary of Extreme Heat Wave. Adv. Meteorol. Sci. Technol. 2015, 5, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, J.; Zhao, M.; Wu, P.; Wang, K. A New Hot Topic for the Research of International Tourism Science: The Impact of Global Climate Change on Tourism Industry. Tour. Trib. 2010, 25, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Ouyang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, C.; Zhang, X. Experimental study of the influence of anticipated control on human thermal sensation and thermal comfort. Indoor Air 2014, 24, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, P.A. Physiological, comfort, performance, and social effects of heat stress. J. Soc. Issues 1981, 37, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Bartels, J.; Antonides, G. Environmentally friendly consumer choices: Cultural differences in the self-regulatory function of anticipated pride and guilt. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enander, A.E. Effects of thermal stress on human performance. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 1989, 15 (Suppl. 1), 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G.; Bartels, J. The Norm Activation Model: An exploration of the functions of anticipated pride and guilt in pro-environmental behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 39, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.R.; Zaval, L.; Weber, E.U.; Markowitz, E.M. The influence of anticipated pride and guilt on pro-environmental decision making. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hengyan, W.; Hongtao, J.; Le, S. Influence mechanism of festival-goers’ experience and satisfaction on loyalty: Case of taihu midi music festival. Areal Res. Dev. 2019, 38, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.; Lin, D. Influence Factors and Effects of Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behaviors Based on Place Theory. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2015, 25, 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Kempton, W.; Boster, J.S.; Hartley, J.A. Environmental Values in American Culture; MIT Press: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay-Hall, P.; Rogers, L. Gaps in mind: Problems in environmental knowledge-behaviour modelling research. Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zeng, T. Destination Support and Tourist Environmentally Responsible Behavior: Ecological Values as a Moderator. Areal Res. Dev. 2023, 42, 106–110+117. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Pei, L.; Zhu, A.; Zhou, C.; Yin, C.; Li, S. Research on Driving Mechanism of Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior in Historical and Cultural Blocks with Environmental Knowledge as Moderating Variable. Areal Res. Dev. 2021, 40, 113–118+137. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, T.-M.; Wu, H.C.; Huang, L.-M. The influence of place attachment on the relationship between destination attractiveness and environmentally responsible behavior for island tourism in Penghu, Taiwan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 1166–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Fan, Y. Measuring Public Environmental Knowledge:The Development of An Indigenous Instrument and Its Assessment. J. Renmin Univ. China 2016, 42, 110–121. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 785. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.T.; Fiske, D.W. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol. Bull. 1959, 56, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994; p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Different methods for testing moderated mediation models: Competitors or backups? Acta Psychol. Sin. 2014, 46, 714–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 176 | 47.4% |

| Male | 195 | 52.6% | |

| Age | 30 and Below | 28 | 7.5% |

| 31–40 | 67 | 18.1% | |

| 41–50 | 90 | 24.3% | |

| 51–60 | 102 | 27.5% | |

| 61 and Above | 84 | 22.6% | |

| Education | Junior High School Education or Below | 81 | 21.8% |

| High School Education/ Technical Secondary School Education | 95 | 25.6% | |

| College Degree | 95 | 25.6% | |

| Bachelor Degree | 78 | 21.0% | |

| Postgraduate Degree | 22 | 5.9% | |

| Monthly income | 5000 and Below | 92 | 24.8% |

| 5001–10,000 | 81 | 21.8% | |

| 10,001–15,000 | 72 | 19.4% | |

| 15,001–20,000 | 55 | 14.8% | |

| 20,001 and Above | 71 | 19.1% | |

| Annual number of trips | 3 and Below | 132 | 35.6% |

| 4–6 | 153 | 41.2% | |

| 7 and Above | 86 | 23.2% |

| Constructs | Indicators | Unstandardized Coefficients | SE | Z-Value | p-Value | Item Loadings | Cronbach’α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTP | CTP1 | 1.000 | 0.797 | 0.829 | 0.830 | 0.620 | |||

| CTP2 | 0.977 | 0.072 | 13.621 | *** | 0.748 | ||||

| CTP3 | 1.003 | 0.071 | 14.205 | *** | 0.815 | ||||

| AP | AP1 | 1.000 | 0.827 | 0.873 | 0.696 | ||||

| AP2 | 0.969 | 0.056 | 17.320 | *** | 0.834 | 0.872 | |||

| AP3 | 0.980 | 0.056 | 17.433 | *** | 0.841 | ||||

| AG | AG1 | 1.000 | 0.718 | 0.774 | 0.777 | 0.538 | |||

| AG2 | 0.940 | 0.086 | 10.974 | *** | 0.694 | ||||

| AG3 | 0.997 | 0.087 | 11.451 | *** | 0.786 | ||||

| ERBI | ERBI1 | 1.000 | 0.755 | 0.921 | 0.923 | 0.666 | |||

| ERBI2 | 1.010 | 0.064 | 15.787 | *** | 0.792 | ||||

| ERBI3 | 1.028 | 0.064 | 16.033 | *** | 0.803 | ||||

| ERBI4 | 1.010 | 0.061 | 16.672 | *** | 0.830 | ||||

| ERBI5 | 1.008 | 0.059 | 17.180 | *** | 0.852 | ||||

| ERBI6 | 1.079 | 0.062 | 17.317 | *** | 0.858 | ||||

| EK | EK1 | 1.000 | 0.760 | 0.833 | 0.833 | 0.556 | |||

| EK2 | 0.936 | 0.070 | 13.320 | *** | 0.737 | ||||

| EK3 | 0.886 | 0.066 | 13.322 | *** | 0.737 | ||||

| EK4 | 0.892 | 0.066 | 13.503 | *** | 0.748 |

| Variables | Anticipatory Pride | Anticipatory Guilt | Environmental Responsibility Behavior Intention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | Model4 | Model5 | Model6 | Model7 | Model8 | |

| Gender | −0.018 | −0.023 | −0.124 | −0.129 | −0.078 | −0.052 | −0.050 | −0.044 |

| (0.120) | (0.118) | (0.086) | (0.083) | (0.112) | (0.109) | (0.093) | (0.093) | |

| Age | −0.092 | −0.113 * | −0.041 | −0.063 | −0.077 | −0.057 | −0.079 * | −0.084 * |

| (0.049) | (0.048) | (0.035) | (0.034) | (0.045) | (0.045) | (0.038) | (0.038) | |

| Education | −0.035 | −0.020 | 0.085 * | 0.101 ** | 0.142 ** | 0.134 ** | 0.119 ** | 0.127 ** |

| (0.050) | (0.049) | (0.036) | (0.034) | (0.046) | (0.046) | (0.039) | (0.039) | |

| Income | 0.100 * | 0.102 * | 0.012 | 0.014 | 0.034 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.020 |

| (0.042) | (0.041) | (0.030) | (0.029) | (0.039) | (0.038) | (0.033) | (0.033) | |

| Annual number of trips | 0.212 ** | 0.181 * | 0.094 | 0.061 | 0.218 ** | 0.160 * | 0.179 ** | 0.173 ** |

| (0.080) | (0.079) | (0.057) | (0.055) | (0.074) | (0.073) | (0.062) | (0.063) | |

| Climate thermal pressure | 0.202 *** | 0.217 *** | 0.033 | 0.019 | 0.028 | |||

| (0.054) | (0.038) | (0.053) | (0.045) | (0.045) | ||||

| Anticipatory guilt | 0.189 ** | 0.310 *** | −0.211 | |||||

| (0.069) | (0.060) | (0.243) | ||||||

| Anticipatory pride | 0.166 *** | −0.166 | 0.282 *** | |||||

| (0.048) | (0.179) | (0.042) | ||||||

| Environmental knowledge | 0.016 | −0.096 | ||||||

| (0.191) | (0.275) | |||||||

| Anticipatory pride × Environmental knowledge | 0.095 * | |||||||

| (0.038) | ||||||||

| Anticipatory guilt × Environmental knowledge | 0.106 * | |||||||

| (0.049) | ||||||||

| Constant | 4.682 *** | 3.791 *** | 5.277 *** | 4.317 *** | 4.466 *** | 2.543 *** | 1.410 | 2.006 |

| (0.299) | (0.378) | (0.215) | (0.265) | (0.278) | (0.502) | (0.992) | (1.379) | |

| Observations | 371 | 371 | 371 | 371 | 371 | 371 | 371 | 371 |

| R-squared | 0.040 | 0.075 | 0.029 | 0.110 | 0.052 | 0.108 | 0.359 | 0.355 |

| Point Estimate | Product of Coefficients | Bootstrapping | Percentage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE | Z | PC 95% CI | BC 95% CI | |||||

| Indirect Effects | ||||||||

| IE1:CTP ⟶ AP ⟶ ERBI | 0.033 | 0.013 | 2.502 | 0.012 | 0.063 | 0.013 | 0.068 | 31.01% |

| IE2:CTP ⟶ AG ⟶ ERBI | 0.041 | 0.016 | 2.605 | 0.014 | 0.075 | 0.014 | 0.075 | 38.13% |

| Direct Effects | ||||||||

| DE:CTP→ERBI | 0.033 | 0.052 | 0.635 | −0.063 | 0.134 | −0.064 | 0.133 | 30.86% |

| Contrasts | ||||||||

| IE1 VS. IE2 | −0.008 | 0.021 | −0.371 | −0.048 | 0.032 | −0.051 | 0.030 | −7.12% |

| Total Indirect Effects | ||||||||

| IE1 + IE2 | 0.075 | 0.021 | 3.610 | 0.038 | 0.118 | 0.041 | 0.122 | 69.14% |

| Total Effects | ||||||||

| IE1 + IE2 + DE | 0.108 | 0.051 | 2.116 | 0.012 | 0.209 | 0.009 | 0.208 | 100.00% |

| Mediator Variable | Moderator Variable | Point Estimation | Standard Error | Z-Value | p-Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticipatory pride | Low anticipatory pride | 0.044 | 0.015 | 2.830 | 0.005 | 0.013 | 0.074 |

| Medium anticipatory pride | 0.068 | 0.020 | 3.320 | 0.001 | 0.028 | 0.107 | |

| High anticipatory pride | 0.087 | 0.028 | 3.070 | 0.002 | 0.031 | 0.142 | |

| Medium-Low | 0.024 | 0.013 | 1.840 | 0.066 | −0.002 | 0.050 | |

| High-Low | 0.043 | 0.024 | 1.840 | 0.066 | −0.003 | 0.089 | |

| High-Medium | 0.019 | 0.010 | 1.840 | 0.066 | −0.001 | 0.040 | |

| Anticipatory guilt | Low anticipatory guilt | 0.046 | 0.020 | 2.290 | 0.022 | 0.007 | 0.085 |

| Medium anticipatory guilt | 0.075 | 0.019 | 4.000 | 0.000 | 0.038 | 0.111 | |

| High anticipatory guilt | 0.098 | 0.027 | 3.610 | 0.000 | 0.045 | 0.151 | |

| Medium-Low | 0.029 | 0.017 | 1.670 | 0.095 | −0.005 | 0.062 | |

| High-Low | 0.052 | 0.031 | 1.670 | 0.095 | −0.009 | 0.112 | |

| High-Medium | 0.023 | 0.014 | 1.670 | 0.095 | −0.004 | 0.050 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, D.; Wang, P.; Guan, J.; Xu, X.; Li, K. Research on the Mechanism of the Influence of Thermal Stress on Tourists’ Environmental Responsibility Behavior Intention: An Example from a Desert Climate Region, China. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1116. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15091116

Li D, Wang P, Guan J, Xu X, Li K. Research on the Mechanism of the Influence of Thermal Stress on Tourists’ Environmental Responsibility Behavior Intention: An Example from a Desert Climate Region, China. Atmosphere. 2024; 15(9):1116. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15091116

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Dong, Pengtao Wang, Jingyun Guan, Xiaoliang Xu, and Kaiyu Li. 2024. "Research on the Mechanism of the Influence of Thermal Stress on Tourists’ Environmental Responsibility Behavior Intention: An Example from a Desert Climate Region, China" Atmosphere 15, no. 9: 1116. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15091116

APA StyleLi, D., Wang, P., Guan, J., Xu, X., & Li, K. (2024). Research on the Mechanism of the Influence of Thermal Stress on Tourists’ Environmental Responsibility Behavior Intention: An Example from a Desert Climate Region, China. Atmosphere, 15(9), 1116. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15091116