Developing a Chained Simulation Method for Quantifying Cooling Energy in Buildings Affected by the Microclimate of Avenue Trees

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Generate a modified weather file using UWG to account for anthropogenic heat and urban environments;

- Create an EnergyPlus–ENVI-met coupling model using the BCVTB platform for microclimate analysis in building energy simulation;

- Evaluate the performance of the coupling method by comparing the simulated energy consumption results;

- Evaluate the impact of street trees on the building’s cooling energy demand.

2. Materials and Methods

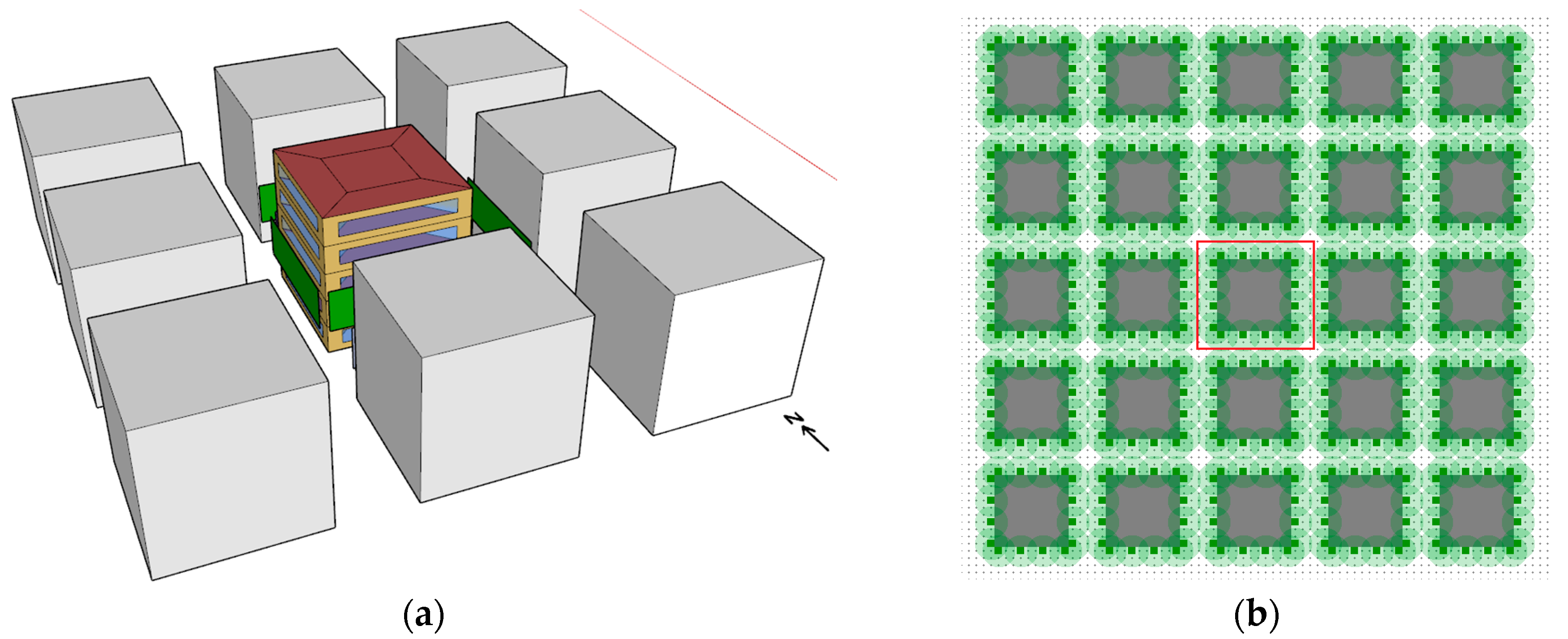

2.1. Urban Context and Domain

2.1.1. Study Area

2.1.2. Building Model

2.2. Simulation Tools and Simulations

2.2.1. Urban Weather Generator (Weather File Modification)

| Setting | Value |

|---|---|

| Reference weather station parameters | |

| Location | Songshan Airport, Taipei City |

| Latitude | 25.067° |

| Longitude | 121.550° |

| Elevation | 6 m |

| Simulation period | 1 year (365 days) |

| Urban parameters | |

| Anthropogenic heat from traffic | Commercial 20 W/m2 [34] |

| Wall albedo | 0.225 [41,42] |

| Roof albedo | 0.225 [43] |

| Road material thermal conductivity | 1.0 W/m·K |

| Road material volumetric heat capacity | 1.6 × 106 J·m3/K |

| Road albedo | 0.2 [26] |

| Traffic heat flux | 20 W/m2 [44] |

| Traffic fractional value range | Monday to Friday: 0.2~0.9 Saturday: 0.2~0.7 Sunday: 0.2~0.4 |

| Window-to-wall ratio | 0.4 |

| Window construction | 8 mm clear glass (single) |

| SHGC | 0.8 |

| Road vegetation fraction | 0 |

| Building program | Large Office |

| Building construction | EnergyPlus building construction |

| Daytime boundary layer height | 1500 m [33] |

| Nighttime boundary layer height (above urban canopy layer) | 80 m |

2.2.2. EnergyPlus (Energy Domain)

2.2.3. ENVI-Met (Microclimate Domain)

2.2.4. Building Control Virtual Test Bed (Coupling Platform)

2.3. Correspondence between ENVI-Met and EnergyPlus

2.4. Coupling Method

2.4.1. Coupling Strategy

2.4.2. Absorbed Direct and Diffuse Solar Radiation

2.4.3. Surface Boundary Conditions (CHTC + RLHTC)

2.4.4. Implementation of Coupling Strategy

3. Results

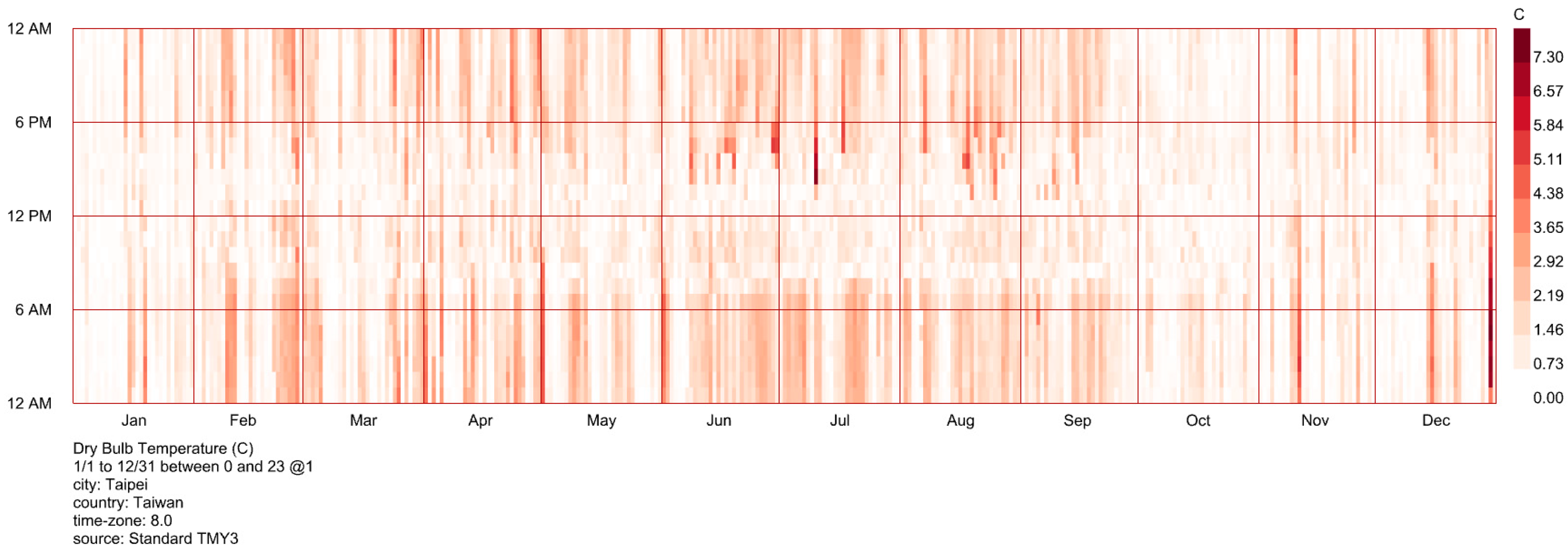

3.1. UWG-Generated Weather Results

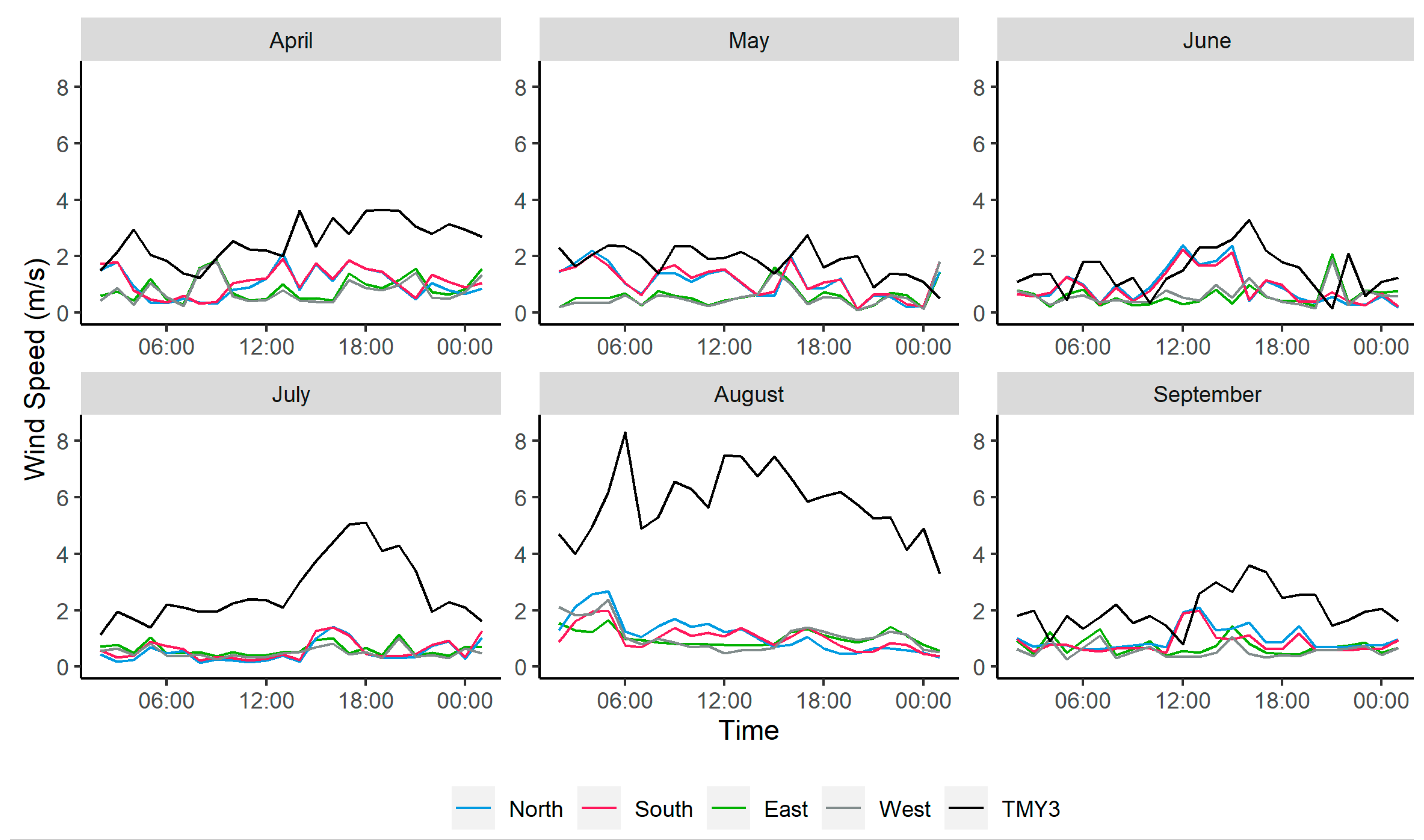

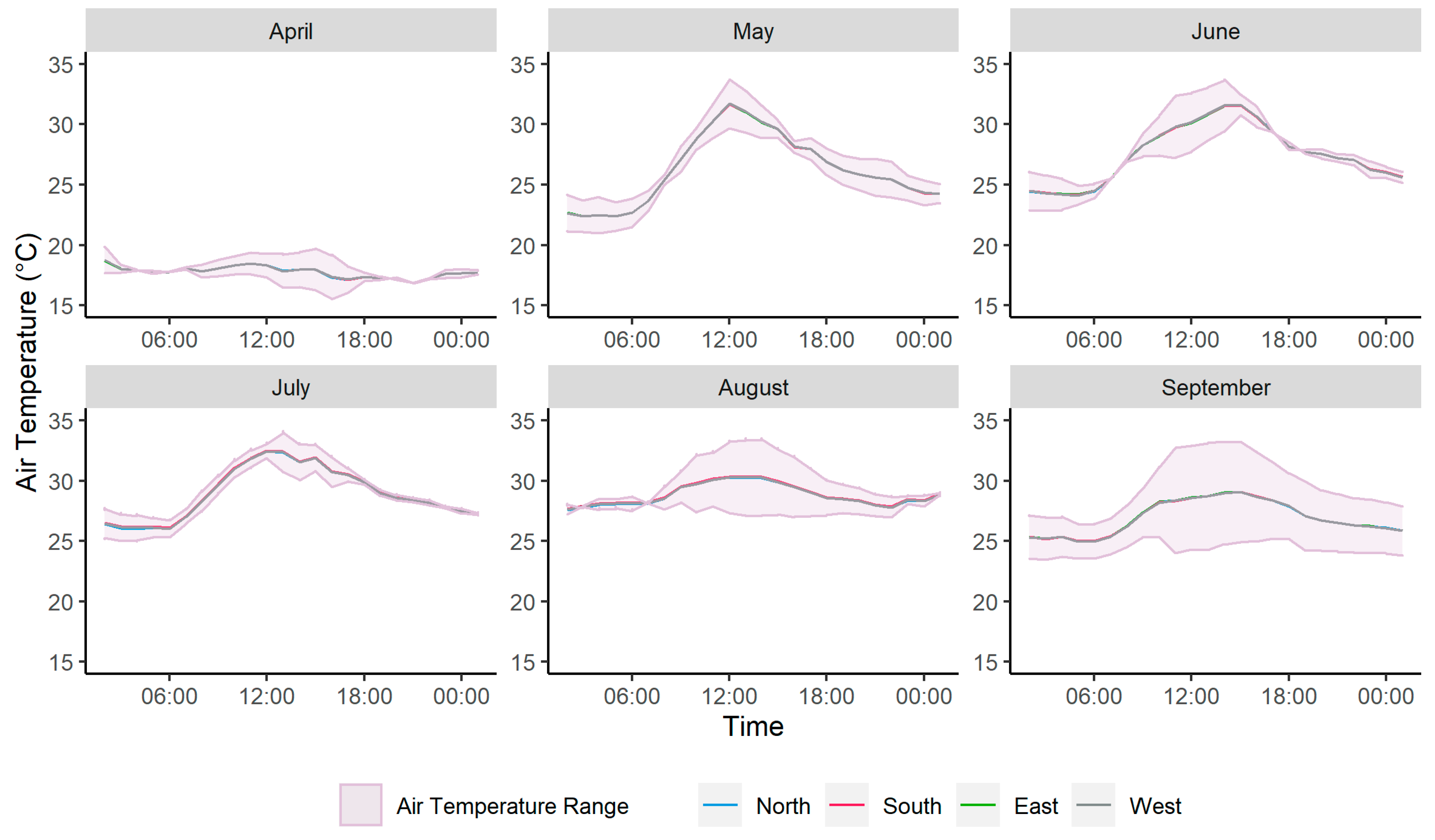

3.2. ENVI-Met-Simulated Microclimate Results

3.3. Results of BCVTB-Coupled Simulations

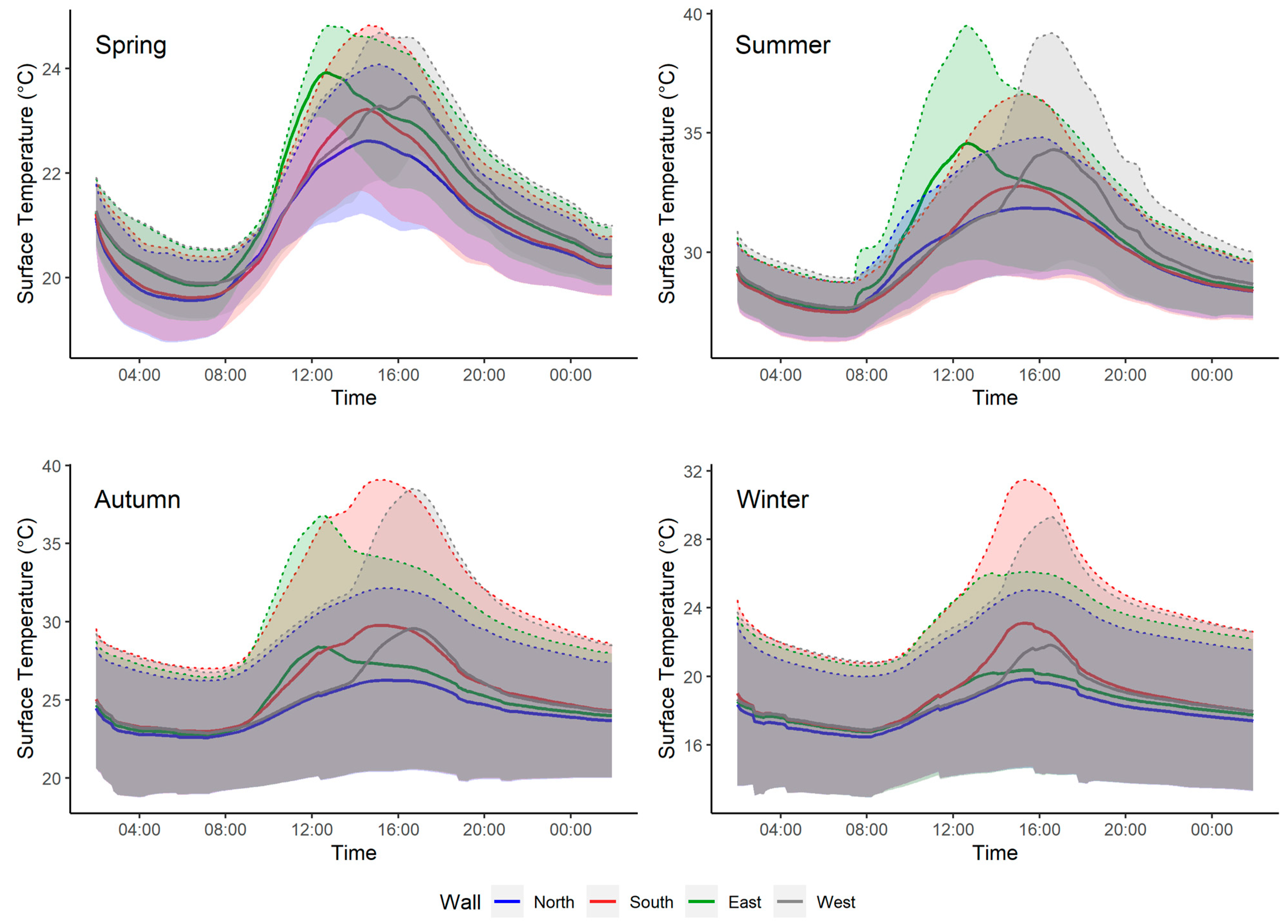

3.3.1. Surface Temperature

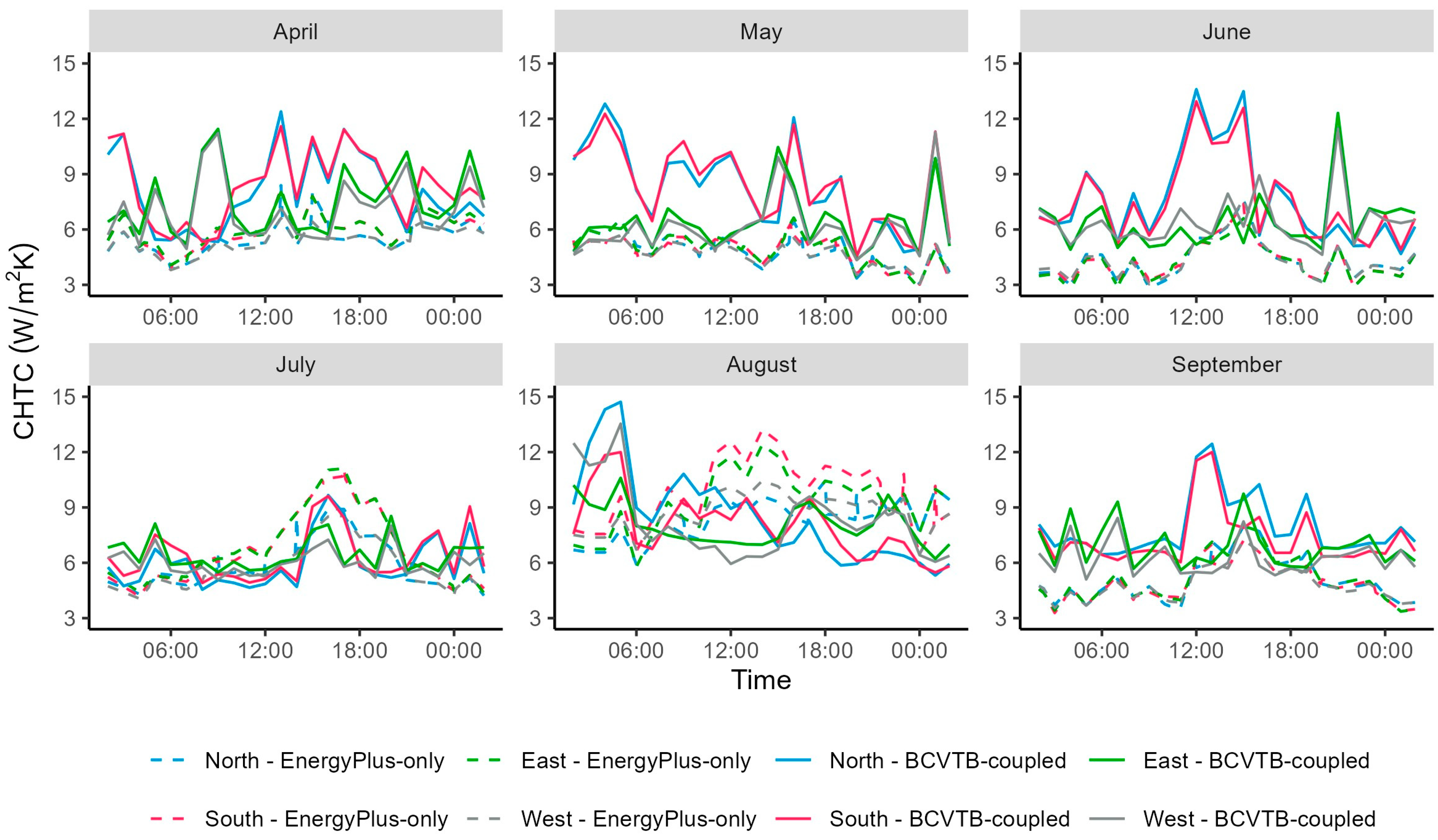

3.3.2. EnergyPlus-Only CHTC vs BCVTB-Coupled CHTC

3.3.3. CHTC vs. Surface Temperature

3.3.4. BCVTB Surface Temperature Results Uncertainty Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Urban Canyon Microclimate Conditions with and without Street Trees

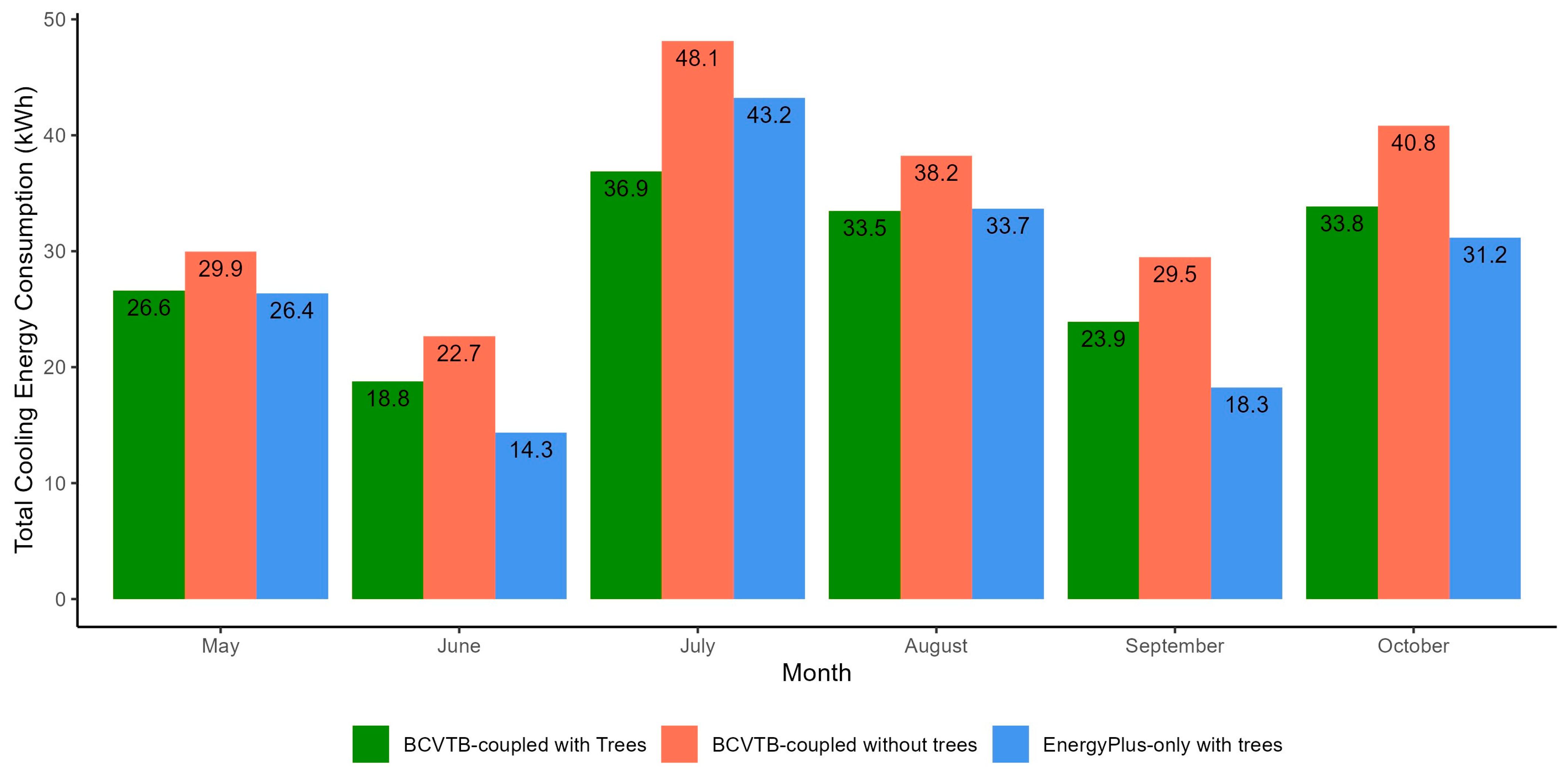

4.2. Impacts of Microclimate Behavior on Cooling Energy Consumption

4.3. Contributions of the Proposed Coupling Method to the Trees’ Cooling Effect on the Building’s Cooling Energy

5. Conclusions

- The UWG is an effective tool for modifying weather files, in that it accounts for the geometry of the local environment and anthropogenic heat flux, which is usually not considered in the modification of weather files for microclimate analysis. Such considerations increased the average air temperature of the weather file by 0.63 °C.

- The coupling of microclimate factors from ENVI-met in EnergyPlus using the BCVTB provides an effective method for accounting for microclimate parameters in building energy simulation. Variables that determine the surface boundary conditions of a building, such as the wind speed and CHTC, are imperative in properly modeling the microclimate. Since most methods for determining the CHTC depend on correlations that are themselves dependent on local wind speed, these values had to be accounted for as accurately as possible using ENVI-met. The average wind speed for the TMY3 was almost 3.5 times higher compared to the ENVI-met values due to the open-space location where the data were collected. Comparing the CHTC values generated by TARP and the BCVTB-coupled system revealed an underestimation of these values on the part of EnergyPlus; the average values were 6.19 W/m2·K and 7.02 W/m2·K, respectively.

- Comparing the EnergyPlus-only simulation and BCVTB simulation with trees with the EnergyPlus-only simulation and BCVTB simulation with removed vegetation revealed that the presence of trees decreased the cooling energy consumption. Notably, even when considering trees merely as transmittance surfaces within EnergyPlus, some level of shading was found to positively impact the reduction in building cooling energy requirements. The average building cooling energy difference between the BCVTB simulations with trees and without trees was 16.7%. Comparing the results from the BCVTB simulation with trees and the EnergyPlus-only simulation showed an underestimation of the cooling energy by EnergyPlus of about 9.3% on average for the summer months. However, the BCVTB simulation lacking vegetation exhibited even higher energy consumption, exceeding the EnergyPlus-only simulation by an average of 23.4%. These results underscore the role of shading structures in reducing cooling energy demand.

- Surface temperatures were observed to rise in the BCVTB simulation after vegetation removal, with temperature increases of up to 9.5% during the hotter months. However, it is worth noting that the mitigating effect of trees on surface temperatures can be reversed during nighttime and early morning hours when heat is trapped beneath the tree canopy.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Nomenclature | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Acronyms | ||

| Absorbed direct and diffuse solar radiation heat flux | ANOVA | Analysis of variance | |

| Building cooling/heating load | ASHRAE | American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers | |

| Convective heat transfer (W) | AHF | Anthropogenic heat flux | |

| Convective heat transfer coefficient (W/m2·K) | BCVTB | Building Control Virtual Test Bed | |

| Conduction heat flux (q/A) | BES | Building energy simulation | |

| Energy change of air in the zone | CHTC | Convective heat transfer coefficient | |

| Emissivity | LAD | Leaf area density | |

| Heat transfer due to infiltration | LAI | Leaf area index | |

| Internal heat gain | RLHTC | Radiative linear heat transfer coefficient | |

| Net longwave radiation heat exchange | RSM | Rural Station Model | |

| Radiative linear heat transfer coefficient (W/m2·K) | SHGC | Solar heat gain coefficient | |

| Sky view factor | TARP | Thermal Analysis Research Program | |

| Surface area (m2) | TMY | Typical meteorological year | |

| Stefan–Boltzmann constant (W/m2·K4) | UC-BEM | Urban Canopy–Building Energy Model | |

| Temperature of building surface (°C) | UBL | Urban boundary layer | |

| Temperature of outside air (°C) | UWG | Urban Weather Generator | |

| Wind speed (m/s) | UHI | Urban heat island | |

| UCM | Urban Climate Model | ||

| VDM | Vertical Diffusion Model | ||

| .idf | EnergyPlus input data file | ||

| .epw | EnergyPlus weather file | ||

References

- Li, X.; Yao, R. Modelling heating and cooling energy demand for building stock using a hybrid approach. Energy Build. 2021, 235, 110740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobman, Y.J.; Elimelech, Y. Microclimate on building envelopes: Testing geometry manipulations as an approach for increasing building envelopes’ thermal performance. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2016, 59, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, V.; Ballarini, I. Refurbishment trends of the residential building stock: Analysis of a regional pilot case in italy. Energy Build. 2016, 132, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, A.; Corchero, C.; Salom, J.; Sanmarti, M. Simulation tools to build urban-scale energy models: A review. Energies 2018, 11, 3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thermal Energy System Specialist (TESS). Trnsys, v18.0; Madison: Wisconsin, WI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ltd, D.B.S. Designbuilder, v7.0; Gloucs: Stroud, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Strachan, P. Esp-r, v13.3.17; Energy Systems Research Unit (ESRU), University of Strathcylde: Glasgow, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Noel, J. Codyba v6.5—Dynamical Behaviour for Buildings; JNLOG Scientific Computing: Lyon, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). Energyplus™, v9.2.0; US Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bouyer, J.; Inard, C.; Musy, M. Microclimatic coupling as a solution to improve building energy simulation in an urban context. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 1549–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Flor, F.S.; Domínguez, S.A. Modelling microclimate in urban environments and assessing its influence on the performance of surrounding buildings. Energy Build. 2004, 36, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, H.; Saito, R.; Sato, R. Numerical Study: How Does a High-Rise Building Affect the Surrounding Thermal Environment by Its Shading? CEPT University: Ahmedabad, India, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kesten, D.; Tereci, A.; Strzalka, A.M.; Eicker, U. A method to quantify the energy performance in urban quarters. HVACR Res. 2012, 18, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strømann-Andersen, J.; Sattrup, P.A. The urban canyon and building energy use: Urban density versus daylight and passive solar gains. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 2011–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frayssinet, L.; Merlier, L.; Kuznik, F.; Hubert, J.-L.; Milliez, M.; Roux, J.-J. Modeling the heating and cooling energy demand of urban buildings at city scale. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 2318–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksek, I.; Karadayi, T. Energy-efficient building design in the context of building life cycle. Energy Effic. Build. 2017, 10, 93–123. [Google Scholar]

- Morille, B.; Lauzet, N.; Musy, M. Solene-microclimate: A tool to evaluate envelopes efficiency on energy consumption at district scale. Energy Procedia 2015, 78, 1165–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, L.; Bruse, M.; Meng, Q. An integrated simulation method for building energy performance assessment in urban environments. Energy Build. 2012, 54, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laboratory, L.B.N. Building Control Virtual Test Bed (bcvtb), v1.6.0; DOE: Washington, WA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lauzet, N.; Rodler, A.; Musy, M.; Azam, M.-H.; Guernouti, S.; Mauree, D.; Colinart, T. How building energy models take the local climate into account in an urban context—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 116, 109390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, S. Urban Energy Information Modeling: A Framework to Quantify the Thermodynamic Interactions between the Natural and the Built Environment that Affect Building Energy Consumption. Ph.D. Thesis, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wetter, M. Co-simulation of building energy and control systems with the building controls virtual test bed. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2011, 4, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharbouch, A.; Berrabah, S.; Bakhouya, M.; Gaber, J.; El Ouadghiri, D.; Idrissi Kaitouni, S. Experimental and co-simulation performance evaluation of an earth-to-air heat exchanger system integrated into a smart building. Energies 2022, 15, 5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, M.; Hien, W.N.; Marcel, I.; Jun Chung, H.D.; Yueer, H.; Zhonqi, Y.; Ji-Yu, D.; Raghavan, S.V.; Son, N.N. A physically-based model of interactions between a building and its outdoor conditions at the urban microscale. Energy Build. 2021, 237, 110788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoka, S. Evaluating the impact of urban microclimate on buildings’ heating and cooling energy demand using a co-simulation approach. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.-T.; Li, Y.-J. Impact of street canyon typology on building’s peak cooling energy demand: A parametric analysis using orthogonal experiment. Energy Build. 2017, 154, 448–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Lo, T.-W.; Shih, W.-Y.; Lin, T.-P. Interpreting air temperature generated from urban climatic map by urban morphology in taipei. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2019, 137, 2657–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, R.-L.; Lin, C.-Y.; Huang, K.-T. Spatial and temporal analysis of urban heat island and global warming on residential thermal comfort and cooling energy in taiwan. Energy Build. 2017, 152, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, B.; Norford, L.; Hidalgo, J.; Pigeon, G. The urban weather generator. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2013, 6, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, B.; Nakano, A.; Norford, L.; Reinhart, C. Urban Weather Generator—A Novel Workflow for Integrating Urban Heat Island Effect within Urban Design Process; International Building Performance Simulation Association: Fairfax, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.H. The Curious Case of Urban Heat Island: A Systems Analysis; MITLibraries: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno, B.; Nakano, A.; Norford, L. Urban weather generator: A method to predic neighborhood-specific urban temperatures for use in building energy simulations. In Proceedings of the ICUC9—9th International Conference on Urban Climate jointly with 12th Symposium on the Urban Environment, Toulouse, France, 20–24 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Chen, F.; Huang, J.C.; Chen, W.C.; Liou, Y.A.; Chen, W.N.; Liu, S.-C. Urban heat island effect and its impact on boundary layer development and land–sea circulation over northern taiwan. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 5635–5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koralegedara, S.B.; Lin, C.-Y.; Sheng, Y.-F.; Kuo, C.-H. Estimation of anthropogenic heat emissions in urban taiwan and their spatial patterns. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 215, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladybug Tools LLC. Ladybug Tools (LBT), v1.2.0; Ladybug Tools LLC: Fairfax, VA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Quah, A.K.L.; Roth, M. Diurnal and weekly variation of anthropogenic heat emissions in a tropical city, singapore. Atmos. Environ. 2012, 46, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, B.; Roth, M.; Norford, L.; Li, R. Computationally efficient prediction of canopy level urban air temperature at the neighbourhood scale. Urban Clim. 2014, 9, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TomTom. Taiwan: Taipei Traffic. 2017. Available online: https://www.tomtom.com/traffic-index/taipei-traffic/ (accessed on 11 June 2017).

- Alchapar, N.; Pezzuto, C.; Correa, E.; Salvati, A. Thermal performance of the urban weather generator model as a tool for planning sustainable urban development. Geogr. Pannonica 2019, 23, 374–384. [Google Scholar]

- Palme, M.; Inostroza, L.; Villacreses, G.; Lobato, A.; Carrasco, C. Urban weather data and building models for the inclusion of the urban heat island effect in building performance simulation. Data Brief 2017, 14, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martien, P.; Akbari, H.; Rosenfeld, A. Light colored surfaces to reduce summertime urban temperatures: Benefits, costs, and implementation issues. In Proceedings of the 9th Miami Internation Congress on Energy and Environment, Miami Beach, FL, USA, 11–13 December 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bretz, S.; Akbari, H.; Rosenfeld, A.; Taha, H. Implementation of Solar-Reflective Surfaces: Materials and Utility Programs; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1992; pp. 1–73, LBL-32467: OSTI ID:10172670. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M.C. Roofs: Design, Application and Maintenance; Polyscience Publications: Québec, QC, Canada, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Sailor, D.J. A review of methods for estimating anthropogenic heat and moisture emissions in the urban environment. Int. J. Climatol. 2011, 31, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, V.; Fabrizio, E. Chapter 5—Steady-state and dynamic codes, critical review, advantages and disadvantages, accuracy, and reliability. In Handbook of Energy Efficiency in Buildings; Asdrubali, F., Desideri, U., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 263–294. [Google Scholar]

- Toparlar, Y.; Blocken, B.; Maiheu, B.; van Heijst, G.J.F. A review on the cfd analysis of urban microclimate. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 80, 1613–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, A.; Bozonnet, E.; Inard, C. Cool materials impact at district scale—Coupling building energy and microclimate models. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2014, 13, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldo, V.L.; Pisello, A.L.; Piselli, C.; Fabiani, C.; Cotana, F.; Santamouris, M. How outdoor microclimate mitigation affects building thermal-energy performance: A new design-stage method for energy saving in residential near-zero energy settlements in italy. Renew. Energy 2018, 127, 920–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoka, S.; Tsikaloudaki, A.; Theodosiou, T. Analyzing the envi-met microclimate model’s performance and assessing cool materials and urban vegetation applications–a review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 43, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyl, C.; Lee, E.; Liu, J.; Neuendorffer, S.; Cheong, E.; John, H.; Tsay, J.; Vogel, B.; Williams, W.; Xiong, Y.; et al. Ptolemy II: Heterogeneous Concurrent Modeling and Design in Java. In Document v2.0.1; Memorandum UCB/ERL M02/23; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, P.; Dai, M.; Xu, P.; Dong, W. Building heating and cooling load under different neighbourhood forms: Assessing the effect of external convective heat transfer. Energy 2019, 173, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Zhang, T.; Tamura, T. Cfd simulation of convective heat transfer on vernacular sustainable architecture: Validation and application of methodology. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6946: 2007; Building Components and Building Elements—Thermal Resistance and Thermal Transmittance—Calculation Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Wetter, M.; Nouidui, T.S. Building Controls Virtual Test Bed User Manual, v1.6.0; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL): Berkely, CA, USA; Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 90. [Google Scholar]

- Albatayneh, A.; Alterman, D.; Page, A.; Moghtaderi, B. Alternative method to the replication of wind effects into the buildings thermal simulation. Buildings 2020, 10, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahsay, M.; Bitsuamlak, G.; Tariku, F. Effect of localized exterior convective heat transfer on high-rise building energy consumption. Build. Simul. 2019, 13, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkordilisz, F.; Zöld, A. Effect of vegetation on wind-comfort. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2016, 824, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri, H.; Blocken, B.; Derome, D.; Carmeliet, J.; Hensen, J.L.M. Cfd analysis of forced convective heat transfer coefficients at windward building facades: Influence of building geometry. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2015, 146, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallati, A.; Vollaro, A.D.L.; Golasi, I.; Barchiesi, E.; Caranese, C. On the impact of urban micro climate on the energy consumption of buildings. Energy Procedia 2015, 82, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-H.; Tsai, H.-H.; Chen, H.-c. Influence of weather factors on thermal comfort in subtropical urban environments. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.-Y. Prediction of higher heating values of biomass from proximate and ultimate analyses. Fuel 2011, 90, 1128–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, P. Experimental and theoretical study on the internal convective and radiative heat transfer coefficients for a vertical wall in a residential building. Energies 2021, 14, 5953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, H.; Bardhan, R.; Kubilay, A.; Li, Q.; Carmeliet, J. The time-evolving impact of tree size on nighttime street canyon microclimate: Wind tunnel modeling of aerodynamic effects and heat removal. Urban Clim. 2023, 49, 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegrini, J.; Dorer, V.; Carmeliet, J. Influence of the urban microclimate in street canyons on the energy demand for space cooling and heating of buildings. Energy Build. 2012, 55, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellier, D.; Ségura, R. Radial growth anisotropy and temporality in fast-growing temperate conifers. Ann. For. Sci. 2020, 77, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzold, S.; Sterck, F.; Bose, A.K.; Braun, S.; Buchmann, N.; Eugster, W.; Gessler, A.; Kahmen, A.; Peters, R.L.; Vitasse, Y.; et al. Number of growth days and not length of the growth period determines radial stem growth of temperate trees. Ecol. Lett. 2022, 25, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sen, S.; Susca, T.; Iaria, J.; Kubilay, A.; Gunawardena, K.; Zhou, X.; Takane, Y.; Park, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Beating urban heat: Multimeasure-centric solution sets and a complementary framework for decision-making. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 186, 113668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Settings | Values |

|---|---|

| Location | Taipei City, latitude: 25.02; longitude: 121.54) |

| Area of building | 2000 m2 |

| Window glazing | U value (W/m2k) = 6.07 SHGC = 0.8 Window-to-wall ratio (WWR) = 0.4 |

| Weather files | UWG generated/modified TMY3 |

| Simulation period | 1 year (365 days) |

| Internal load | Occupancy (people/m2) = 0.15 Lighting (W/m2) = 15 Electric equipment (W/m2) = 10 |

| HVAC system | Variable air volume (VAV) Chiller COP = 5.0 Cooling setpoint: 24 °C Heating setpoint: none |

| Surface convection algorithm | TARP [Table A1] |

| Ground reflectance and temperature | ENVI-met output data |

| Trees | Transmittance: 0.07 |

| Settings | Values |

|---|---|

| Domain | 120 m × 120 m × 18 m |

| Mesh size | dx = 2 m, dy = 2 m, dz = 2 m |

| Environment | With greenery |

| Trees | General structure: cylindric, large trunk, dense, medium (15 m), Albedo: 0.12, LAI: 2.3 m2m2, LAD: 2 m2m3 Foliage transmittance: 0.10, Leaf type: conifer Leaf weight: 100 g/m2 Depth of roots: 9 m Diameter of roots: 7 m CO2 fixation type: C3-Plant |

| Simulation period | Coldest and hottest day of every month, January to December based on TMY3 |

| Reference time zone | GMT + 8:00 |

| Weather data | Simple forcing with data from Taipei TMY3 |

| Ground | Asphalt road—albedo: 0.2, Concrete gray pavement—albedo: 0.5, Loamy soil—albedo: 0.0 |

| Variables Calculated in the Coupling Platform | Input Source | |

|---|---|---|

| EnergyPlus | ENVI-Met | |

| Absorbed direct and diffuse solar radiation (1) | ||

| Incident solar radiation | ✓ | |

| Shadowing effects | ✓ | |

| Convective flux change with outside air– surface boundary conditions (2) | ||

| Surface temperature | ✓ | |

| Air temperature near surface | ✓ | |

| Wind speed | ✓ | |

| Longwave radiation flux | ||

| Outside surface temperature | ✓ | |

| Outside air temperature | ✓ | |

| Heat and Moisture via infiltration (3) | ||

| Infiltration schedule | ✓ | |

| Indoor zone air temperature | ✓ | |

| Outdoor dry-bulb temperature | ✓ | |

| Wind speed around building surface | ✓ | |

| Variable | Taipei TMY3 (Rural) | UWG-Modified TMY3 (Urban) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 23.33 | 23.96 |

| Median | 23.8 | 24.4 |

| Mode | 27.6 | 29.2 |

| Standard Deviation | 5.65 | 5.74 |

| Kurtosis | −0.66 | −0.75 |

| Range | 8.7~37.1 | 9.5~37.1 |

| Metric | Average Values | Maximum Values | Minimum Values | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | South | East | West | North | South | East | West | North | South | East | West | |

| MAE (°C) | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.22 | 0.64 | 0.53 | 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| MBE (°C) | −0.17 | −0.09 | −0.07 | −0.09 | −0.62 | −0.45 | −0.50 | −0.53 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Flowers, B.; Huang, K.-T. Developing a Chained Simulation Method for Quantifying Cooling Energy in Buildings Affected by the Microclimate of Avenue Trees. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1150. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15101150

Flowers B, Huang K-T. Developing a Chained Simulation Method for Quantifying Cooling Energy in Buildings Affected by the Microclimate of Avenue Trees. Atmosphere. 2024; 15(10):1150. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15101150

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlowers, Bryon, and Kuo-Tsang Huang. 2024. "Developing a Chained Simulation Method for Quantifying Cooling Energy in Buildings Affected by the Microclimate of Avenue Trees" Atmosphere 15, no. 10: 1150. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15101150

APA StyleFlowers, B., & Huang, K.-T. (2024). Developing a Chained Simulation Method for Quantifying Cooling Energy in Buildings Affected by the Microclimate of Avenue Trees. Atmosphere, 15(10), 1150. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15101150