Abstract

We previously found that cigarette sidestream smoke particulate matter (CSSP) could activate estrogen receptor ERα to generate estrogen-like tumor-promoting effects. This study sought to identify the compounds responsible for CSSP estrogenicity. We first identified the component compounds using a combination of GC-MS and mass spectral matching. Based on computational estrogenicity prediction, nine potential estrogenic compounds were selected for second GC-MS identification and quantification. Their estrogenic activities at levels detected in the CSSP were verified using an estrogen-responsive reporter assay. Only catechol, a possible human carcinogen, showed significant estrogenic activity, but the activity was too low to justify CSSP estrogenicity. Even so, the mixture of these compounds reconstituted according to their contents in CSSP produced almost one third of the estrogenic activity of CSSP. These compounds acted synergistically to induce greater estrogenic effects at levels without apparent estrogenic activities. Nicotine accounted for approximately 16% of the total CSSP mass. The high abundance raises concerns about nicotine toxicity, including potentially working together with estrogenic chemicals to promote tumor growth. In summary, this study presents a tiered testing approach to identify estrogenic chemicals. Although no individual components are accountable for CSSP estrogenicity, the low-dose mixture effects of CSSP components warrant public health concerns.

1. Introduction

Cigarette smoke is a significant source of indoor pollutants. When released indoors, cigarette smoke can linger in the air and settle on surfaces, exposing nonsmokers to the harmful chemicals in the smoke. Since 1964, 2.5 million nonsmokers have died due to exposure to secondhand smoke. Children, pregnant women, and individuals with pre-existing health conditions are particularly vulnerable to the harmful effects of secondhand smoke [1]. Secondhand smoke is composed of mainstream and sidestream cigarette smoke. Sidestream smoke, released directly from the burning tip of a cigarette, makes up about 85% of secondhand smoke [2]. In addition, cigarette sidestream smoke particulate matter (CSSP) has been reported to be four times more toxic than mainstream smoke particulate matter on a per gram basis [3].

CSSP possesses estrogen-like properties [4]. The estrogenic activity of CSSP has raised concerns because of the probability of mimicking or disrupting the actions of estrogen in a variety of physiological functions and pathological processes, including lung cancer development. Indeed, estrogen is a risk factor for lung cancer. In comparison with men, women have a higher susceptibility to tobacco carcinogens and a greater chance of developing lung cancer at a young age (<50 years, usually not yet reaching menopause) [5,6]. Women who have never smoked also have a higher risk of lung cancer, primarily lung adenocarcinoma, than nonsmoking men. Serum estrogen levels are inversely associated with survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [7,8]. NSCLC tumor tissues also contain higher concentrations of estrogen (~2.2-fold) than non-neoplastic tissues from the same patients. Tumor estrogen concentrations are positively associated with tumor sizes in nuclear estrogen receptor ERα-positive patients, but not ERα-negative patients [9]. Our previous study demonstrated that CSSP generated from a leading brand of cigarette in Taiwan did not only activate the transcriptional activity of ERα as 17β-estradiol (E2, the primary form of endogenous estrogen), but also enhanced E2-induced ERα activity in human lung adenocarcinoma cells. Exposure to either E2 or CSSP significantly increased the proliferation and migration of ERα-expressing lung adenocarcinoma cells [4].

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) bear structural resemblance to steroid hormones, such as E2. A number of PAHs have been shown to be able to bind and activate ERα in human breast cancer cells and rat uterus [10,11]. We examined the contents of 22 PAHs in CSSP. In total, 17 PAHs were detected, constituting about 0.022% of the entire mass [12]. However, the reconstituted PAH mixture failed to activate ERα as CSSP [4]. Metals such as Al, As, Ba, Cd, Ni, and Pb can also induce estrogen-mimetic signaling via the activation of ERα, hence increasing the estrogen-like cancer risk [13]. Likewise, we confirmed that the estrogenic activity of CSSP is not attributable to metals found in CSSP [14]. This study aims to identify the component compounds contributing to the estrogenicity of CSSP. A tiered testing approach is taken in this study. We detect a synergistic mixture response among compounds without apparent estrogenic activities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of CSSP Extracts

The CSSP was prepared from Long Life cigarettes, a leading brand in Taiwan, following a standard smoking procedure approved by the USA Federal Trade Commission and the International Standard Organization [15]. A 47 mm glass fiber filter with a pore size of 1 μm (Life Sciences, East Hills, NY, USA) was used to capture CSSP. After the measurement of the net dry weight of the CSSP absorbed on the filter, the CSSP was ultrasonically extracted from the filter using 20 mL methanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 30 min. The extract was dried using the Savant Speed Vac SPD121P (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 1200 rpm and 40 °C. The vacuum-dried CSSP was then dissolved in ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) to 180 mg/mL.

2.2. Compound Identification by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

After a ten-fold dilution with ethanol, two CSSP extract samples were analyzed using an Agilent 7890B GC system coupled with Agilent 5977A MSD (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The GC was equipped with an Agilent HP-5MS column (60 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm) using helium as the carrier gas, which flowed at a constant rate of 1.4 mL/min. The oven temperature was held at 80 °C for 2 min, and then elevated to 300 °C at a speed of 6 °C/min and maintained at 300 °C for 18 min. The inlet was maintained at 300 °C. The samples were injected at 1 μL with a split ratio of 50:1. The mass spectrometer was operated in the electron ionization mode at 230 °C with an ionizing voltage of 70 eV. Data were acquired in the scan mode with a mass range of 45–650 m/z. Component organic compounds were tentatively identified by searching the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Mass Spectral Database NIST11.

Component compounds with potential estrogenicities were verified and quantified by the GC-MS analysis described above, except that the samples were injected in a 5:1 split mode using a Gerstel autosampler (Gerstel GmbH, Mülheim, Germany). The ionic signals of standard compounds were profiled at multiple concentrations using the scan mode (45–650 m/z). The concentrations of analytes were measured against the corresponding calibration curves (R2 > 0.995) under the selected ion monitoring mode that was determined based on the ion profile of standards. Reference-standard compounds of catechol and hydroquinone were purchased from Nihon Shiyaku Reagent (Kobe, Japan), 4-ethylphenol from Dr. Ehrenstorfer (Augsburg, Germany), 2-phenylphenol, 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol, methoxyhydroquinone, and nicotine from Sigma-Aldrich, 2-pyrrolidinone from Alfa Aesar (Heysham, Lancashire, UK), and triacetin from Nippon Shiyaku (Kyoto, Japan).

2.3. Computational Estrogenic Potential Prediction

The estrogenic potentials of the tentative component compounds were estimated using the ToxCast ER model and the CERAPP model publicly available in the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) CompTox Chemicals Dashboard [16,17]. The dashboard also provides open access to the data of 48 ERα bioassays developed by the Toxicology in the 21st Century Program (Tox21), the Center for Computational Toxicology and Exposure (CCTE) Laboratories, and companies under contract to the US EPA such as ACEA Biosciences, Attagen (ATG), Novascreen (NVS), and Odyssey Thera (OT). The AC50 (half-maximal activation concentration) values derived from multi-concentration experiments are provided for active hit calls.

2.4. Estrogenic Activity Measurement by Estrogen-Responsive Reporter Assay

The estrogenicities of CSSP component compounds were examined by the transfection of an estrogen-responsive reporter, ERE-Luc, into an ERα-inducible cell line engineered from the human lung adenocarcinoma CL1-5 cell line in our laboratory [18]. The ERα-inducible cell line was routinely maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific). To reduce the background noise in the estrogenic activity measurement, the cells were cultured in phenol red-free RPMI-1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) and charcoal/dextran-stripped FBS in experiments. The transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocol. In addition to ERE-Luc, a β-galactosidase expression plasmid, pSV40-βgal, was co-transfected into cells as the transfection efficiency control. After 8 h transfection, the cells were rinsed and cultured in phenol red-free RPMI-1640 plus 3% charcoal/dextran-stripped FBS overnight before the induction of ERα expression by adding 1 μg/mL doxycycline (Sigma-Aldrich). Then, 24 h after doxycycline addition, the ERα-induced cells were further treated with 1 nM E2 (Sigma-Aldrich), 20 μg/mL CSSP, 1% dimethyl sulfoxide (vehicle control, Sigma-Aldrich), individual component compounds at concentrations found in 20 μg/mL CSSP, and the mixture of component compounds (OCM) for 24 h. Upon being activated by E2 or estrogenic compounds, ERα could bind to the estrogen-responsive element (ERE) and consequently induce the expression of the downstream luciferase reporter gene (Luc), which was manifested by its enzyme activity. Luciferase reporter activity was determined by normalization to the corresponding β-galactosidase activity, and the activities of both enzymes were measured using the Promega Luciferase and β-Galactosidase Assay Systems (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The experiments were performed in three or four replicas as indicated in the figure caption. The reporter activity in relation to the vehicle control was calculated and expressed as mean ± SE. The significances of differences between the treatments (p < 0.01) were assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test (SPSS Statistics 19, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Mass Spectrum-Based Compound Identification

Prior to the identification of the unknown organic components of CSSP by GC-MS, two lengths of HP-5MS column (30 m vs. 60 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm) were evaluated using GC-FID. The chromatogram of CSSP acquired from the 60 m column displayed superior resolution than that from the 30 m column. The 60 m HP-5MS column was used in the GC-MS analyses performed in this study. To increase the accuracy of unknown compound identification, two independent CSSP extracts were analyzed. The peaks that were detected in both extracts were identified by searching for matching mass spectra in the NIST Standard Reference Database. Thirty compounds exhibited a match percentage greater than 75% (Table 1), and each compound’s highest match percentage score between the two samples is provided. Additionally, Table 1 lists the retention time for each tentatively identified compound, indicating the amount of time it was eluted from the 60 m HP-5MS column following the sample injection.

Table 1.

Preliminary chemical identification by GC-MS and mass spectral matching.

3.2. ER-Modulating Potential Prediction

To facilitate the identification of estrogenic component compounds, the ER-modulating potentials of the compounds listed in Table 1 were estimated by the ToxCast ER model and the CERAPP model. The ToxCast ER model incorporates results from 18 ToxCast ER assays to improve model prediction. This model scores estrogenicity by calculating the area under the concentration–response curve (AUC), which ranges from 0 to 1. AUC values <0.001 are considered to be null in ER activity and given a score of 0 in the ToxCast ER score system [16]. Four tentatively identified compounds have an ER agonist score >0.001. They are, from high to low score, triacetin, catechol, 2-phenylphenol, and 4-ethylphenol (Table 2).

Table 2.

Forecasting the ER-modulating potentials of putative organic components in cigarette sidestream smoke particulate matter.

The CERAPP consensus model is formed by the integration of 40 categorical models and 8 continuous models derived from different quantitative structure–activity relationships and structure-based docking predictions. The CERAPP program (Collaborative Estrogen Receptor Activity Prediction Project) also curates the ER-related experimental data in the literature. The CERAPP predictions are categorized into three groups: ER binders, ER agonists, and ER antagonists, and their respective potencies of binding, agonistic activity, and antagonistic activity are evaluated by comparing them to a library of 45 reference chemicals [17]. While methylhydroquinone and triacetin are known to have very low binding affinities to ER based on literature reports, CERAPP modeling predicts that 4-ethylphenol, 2-phenylphenol, 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol, and 2-pyrrolidinone have the potential to bind, agonize, or antagonize ER. However, all of the predictive binding, agonistic, and antagonistic potencies are weak or very weak (Table 2).

The US EDSP21 (Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program in the 21st Century) and Tox21 programs have employed high-throughput biochemical- and cell-based assays to screen more than 10,000 chemicals for potential endocrine-disrupting or toxic bioactivities. Assay data are collected and curated in the EPA’s CompTox Chemicals Dashboard [19,20]. Our search results indicate that except 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol and methylhydroquinone, the compounds listed in Table 2 all tested positive for ERα agonist activity. The bioassays and AC50 data are summarized in Table 3. The ATG_ERE_CIS and ATG_ERa_TRANS assays seem to have higher sensitivities to obtain active hit calls. Six of the eight compounds listed in Table 3 show positive results in these two assays. The ATG_ERE_CIS assay measures the level of reporter mRNA that is stimulated by endogenous human ERα through the cis-acting response element ERE, while the ATG_ERa_TRANS assay quantifies reporter mRNA that is induced by the hybrid transcription factor GAL4-ERα through the GAL4-binding sequence. It appears that the ATG_ERE_CIS assay is used to assess the agonistic effect of a compound on the holoreceptor, while the ATG_ERa_TRANS assay evaluates the impact on the trans-activating potential of the ERα ligand-binding domain [21].

Table 3.

Summary of the ERα agonist activities of putative estrogenic component compounds determined by EDSP21 and Tox21 assays.

3.3. Identification of Estrogenic Components

Our previous study found that phenanthrene is the most abundant PAH present in the CSSP extract generated from the Taiwanese brand [12]. However, the mixture reconstituted according to the contents of PAHs in CSSP lacks estrogenic activity [4]. Therefore, we excluded phenanthrene from the second GC-MS identification and quantification (Table 4). As expected, CSSP has a high nicotine content (3694.64 μg/cigarette), constituting about 16% of the total mass. The second most abundant component identified in the GC-MS analysis is catechol, which is possibly carcinogenic to humans (IARC Group 2B) [22]. The amount of catechol in CSSP is 294.54 μg per cigarette, only about 8% of the nicotine mass. Hydroquinone, the third most abundant component (221.55 μg/cigarette) identified here, is an IARC Group 3 carcinogen that may cause cancer in animals, but has no acknowledged carcinogenicity in humans [23]. On the contrary, 2-phenylphnenol is not detectable in CSSP (Table 4).

Table 4.

Amounts of putative estrogenic components in cigarette sidestream smoke particulate matter.

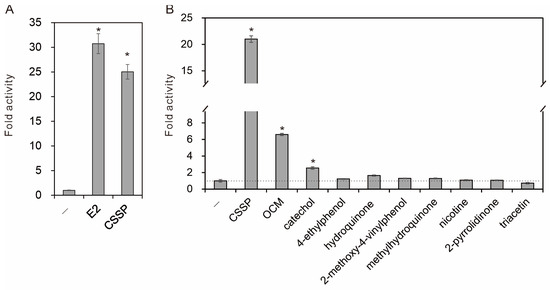

An estrogen-responsive reporter assay was used to evaluate estrogenicity. CSSP at 20 μg/mL significantly induced reporter activity at 1 nM E2, although to a lesser extent (Figure 1A). Among the identified components, only catechol exhibited significant estrogenic activity at the concentration detected in CSSP, but its activity was much lower than that of CSSP (2.56 ± 0.15-fold vs. 21.01 ± 0.62-fold). The organic chemical mixture (OCM) reconstituted from the identified components according to their contents in CSSP (Table 4) produced remarkably higher estrogenic activity than the additive sum of their individual activities (6.60-fold vs. 3.88-fold). OCM accounted for almost one third of the estrogenic activity of CSSP (Figure 1B). Our findings suggest that the components of CSSP act together to activate estrogen receptors. The synergistic interaction may cause adverse estrogenic effects on people exposed to CSSP.

Figure 1.

Estrogenic activity analysis. The estrogenic potencies of compounds and mixtures were assessed by transfection of an ERE-Luc reporter into ERα-inducible human lung adenocarcinoma cells. (A) The transfected cells were treated with vehicle (-), 17β-estradiol (E2, 1 nM), and cigarette sidestream smoke particulate matter (CSSP, 20 μg/mL) (n = 3). (B) Individual components of CSSP were tested at concentrations found in CSSP alongside their reconstituted mixture (OCM) and CSSP (n = 4). After 24 h of treatment in the presence of ERα induction, reporter activities were measured to evaluate the levels of ERα activation. All activities were compared with the vehicle control, and statistical significance (p < 0.01) was indicated by an asterisk (*).

4. Discussion

In addition to our research on CSSP, several studies have shown the presence of estrogenicity in cigarette smoke particulate matter generated from American, Japanese, and reference cigarettes. However, none of the latter studies sought to identify the specific components responsible for the estrogenicity or examined their estrogenic activity at the levels found in cigarette smoke [24,25,26,27]. Although we have not found individual components accountable for CSSP estrogenicity, we show that a number of CSSP components act together to activate estrogen receptors synergistically. Previously, we demonstrated that CSSP can enhance ERα activity even when the receptor is saturated by E2 [4]. These component compounds may serve more of a function than acting as an ER ligand. The synergistic agonism may involve coactivator recruitment or the steric modification of ER [28,29]. It is also likely that some components in CSSP can induce certain enzyme activities that transform a component compound from pro-estrogenic to estrogenic [30].

Toxicological studies are generally aimed at single chemicals. However, the single-chemical practices fail to account for the combined effects of mixtures, particularly when components are present at low levels [31]. Our findings highlight the limitations of the conventional effect additive approach and the threshold concept in assessing the endocrine-disrupting properties of cigarette smoke. Epidemiological studies in humans have also demonstrated that exposure to mixtures of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) can have a synergistic impact on health outcomes, such as obesity, diabetes, and reproductive disorders [32]. The regulation of EDCs should take the mixture effect and the potential for greater harm into consideration.

Catechol is the sole component in CSSP that demonstrates significant estrogenic activity at the detected level, but the activity is too low to justify the overall estrogenicity of CSSP. Although triacetin has a slightly higher ToxCast ER score than catechol (0.0182 vs. 0.0155), it is only present in half the amount of catechol in CSSP (157.57 μg vs. 294.54 μg per cigarette). In addition, triacetin had an AC50 almost five times higher than catechol (104.15 μM vs. 21.42 μM) in the ATG_ERE_CIS assay, which assesses the competence of a compound to activate human ERα using an ERE-reporter similar to the ERE-Luc reporter assay conducted in this study. Given these results, it is not surprising that triacetin did not induce the ERE-Luc reporter when tested on its own.

Catechol is not only an estrogenic chemical, but also a possible human carcinogen (IARC group 2B) [22]. Hydroquinone is also known to be carcinogenic in experimental animals (IARC group 3) [23]. In fact, more than 60 carcinogens, including strong carcinogens such as PAHs, nitrosamines, and aromatic amines, have been detected in mainstream and sidestream cigarette smoke [33]. The modulation of ER signaling may modify the carcinogenic effects of tobacco carcinogens. At least, the induction of ERα signaling promotes the development of hormone-dependent cancers such as breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancers [34]. ERα activation is also critical for the proliferation, migration, cisplatin resistance, and tumor growth of human lung adenocarcinoma cells [4,35,36].

Despite not being a potent ER agonist, nicotine can efficiently act on nicotinic cholinergic receptors in the brain to trigger the release of dopamine and other neurotransmitters that produce pleasant feelings. Withdrawal symptoms such as craving can occur upon the decline in brain nicotine levels. Addiction to nicotine is a key cause for smoking-related health problems [37]. There is also evidence suggesting that nicotine can convert to carcinogenic nitrosamines endogenously in humans [38]. It has also been demonstrated that nicotine and estrogen additively increase the angiogenesis and tumor growth of human bronchioloalveolar carcinoma xenografts implanted in ovariectomized nude mice [39]. Accordingly, estrogenic chemicals may promote tumor development when working together with nicotine. Furthermore, nicotine can readily cross the placenta to affect fetal development, potentially causing congenital anomalies [40].

A recommended exposure level (REL) of 0.5 mg/m3 for nicotine has been established based on the no-adverse-effect level (NOAEL) from a two-year inhalation rat study. To improve the protection of workers from potential harm, the Health Council of the Netherlands has reviewed the study and proposed a health-based occupational exposure limit of 0.1 mg/m3. This new limit is determined by reducing the exposure duration from 20 h to 8 h per day and incorporating an uncertainty factor of 9 for interspecies variation [41]. Considering the Dutch guideline and the high nicotine content in CSSP (3694.64 μg/cigarette), it is possible for individuals to be exposed to harmful levels of nicotine if they smoke two cigarettes simultaneously or consecutively in a poorly ventilated room of 60 m3 (4 m × 5 m × 3 m).

5. Conclusions

Indoor pollution caused by secondhand smoke is a significant issue in homes, workplaces, and public spaces such as restaurants and bars. Exposure to secondhand smoke can pose serious health risks to individuals. The estrogenic activity of secondhand smoke is one of the subjects of concern. In this study, we employed GC-MS analysis, ToxCast ER model, and CERAPP model to identify potential estrogenic component compounds in CSSP. The ER-modulating capabilities of these components were further identified by an estrogen-responsive reporter assay. Only catechol was found to exhibit significant estrogenic activity at the detected level, but its activity was too low to justify the estrogenic capacity of CSSP. The mixture reconstituted according to the contents of these components in CSSP produced much higher estrogenic activity than the additive sum of the activities displayed by the individual components. The mixture activity accounted for almost one third of the CSSP estrogenicity. The synergistic agonistic action of CSSP components on estrogen receptors, even at levels below the thresholds, underscores the potential endocrine-disrupting risks associated with secondhand smoke exposure. In addition to estrogenicity, CSSP components have other toxic effects, such as (pro-)carcinogenicity, tumor promotion, and teratogenicity. The interaction of various effects of components determines the outcome of secondhand smoke exposure. More research is needed to understand the complex interaction. Our findings highlight the limitations of traditional toxicological approaches that focus on single chemicals and neglect mixture effects. Low-dose mixture effects need to be taken into consideration when assessing the health impacts of secondhand smoke.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.-A.L. and C.-J.L.; analysis, C.-J.L.; data curation, L.-A.L. and C.-J.L.; draft and visualization, C.-J.L.; review and editing, L.-A.L.; funding acquisition, L.-A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Health Research Institutes grant number EM-110-PP-06.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in Table 2 and Table 3 are openly available from the CompTox Chemicals Dashboard (https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard/, accessed on 1 March 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014.

- IARC. Tobacco smoke and involuntary smoking. In IARC Monographys on the Evaluation of the Carcinogenic Risk to Human; IARC, WHO: Lyon, France, 2004; Volume 83, pp. 1–1473. [Google Scholar]

- Schick, S.; Glantz, S. Philip Morris toxicological experiments with fresh sidestream smoke: More toxic than mainstream smoke. Tob. Control 2005, 14, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, L.C.; Cheng, L.C.; Lee, C.H.; Lin, C.J.; Chen, P.Y.; Li, L.A. Estrogen and cigarette sidestream smoke particulate matter exhibit ERalpha-dependent tumor-promoting effects in lung adenocarcinoma cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2017, 313, L477–L490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henschke, C.I.; Yip, R.; Miettinen, O.S. Women’s susceptibility to tobacco carcinogens and survival after diagnosis of lung cancer. JAMA 2006, 296, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Radzikowska, E.; Glaz, P.; Roszkowski, K. Lung cancer in women: Age, smoking, histology, performance status, stage, initial treatment and survival. Population-based study of 20 561 cases. Ann. Oncol. 2002, 13, 1087–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivo-Marston, S.E.; Mechanic, L.E.; Mollerup, S.; Bowman, E.D.; Remaley, A.T.; Forman, M.R.; Skaug, V.; Zheng, Y.L.; Haugen, A.; Harris, C.C. Serum estrogen and tumor-positive estrogen receptor-alpha are strong prognostic classifiers of non-small-cell lung cancer survival in both men and women. Carcinogenesis 2010, 31, 1778–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, H.; Oldham, F.B.; Bandstra, B.; Sandalic, L.; Bianco, J.; Bonomi, P.; Singer, J.W. Serum-free estradiol (E2) levels are prognostic in men with chemotherapy-naive advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and performance status (PS) 2. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 7683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niikawa, H.; Suzuki, T.; Miki, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Nagasaki, S.; Akahira, J.; Honma, S.; Evans, D.B.; Hayashi, S.; Kondo, T.; et al. Intratumoral estrogens and estrogen receptors in human non-small cell lung carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 4417–4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummer, V.; Maskova, J.; Zraly, Z.; Neca, J.; Simeckova, P.; Vondracek, J.; Machala, M. Estrogenic activity of environmental polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in uterus of immature Wistar rats. Toxicol. Lett. 2008, 180, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vondracek, J.; Kozubik, A.; Machala, M. Modulation of estrogen receptor-dependent reporter construct activation and G0/G1-S-phase transition by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells. Toxicol. Sci. 2002, 70, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.L.; Hsieh, D.P.; Li, L.A. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in cigarette sidestream smoke particulates from a Taiwanese brand and their carcinogenic relevance. Chemosphere 2011, 82, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbre, P.D. Metalloestrogens: An emerging class of inorganic xenoestrogens with potential to add to the oestrogenic burden of the human breast. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2006, 26, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.C.; Lin, C.J.; Liu, H.J.; Li, L.A. Health risk of metal exposure via inhalation of cigarette sidestream smoke particulate matter. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 26, 10835–10845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeler, C.L. Cigarette testing and federal trade commission: A historical overview. In Smoking and Tobacco Control; National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 1996; Volume 7, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, P.; Judson, R.S.; Casey, W.M.; Kleinstreuer, N.C.; Thomas, R.S. Screening Chemicals for Estrogen Receptor Bioactivity Using a Computational Model. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 8804–8814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, K.; Abdelaziz, A.; Rybacka, A.; Roncaglioni, A.; Tropsha, A.; Varnek, A.; Zakharov, A.; Worth, A.; Richard, A.M.; Grulke, C.M.; et al. CERAPP: Collaborative Estrogen Receptor Activity Prediction Project. Environ. Health Perspect 2016, 124, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, L.C.; Cheng, L.C.; Lin, C.J.; Li, L.A. Dioxin and estrogen signaling in lung adenocarcinoma cells with different aryl hydrocarbon receptor/estrogen receptor alpha phenotypes. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013, 49, 1064–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.S.; Paules, R.S.; Simeonov, A.; Fitzpatrick, S.C.; Crofton, K.M.; Casey, W.M.; Mendrick, D.L. The US Federal Tox21 Program: A strategic and operational plan for continued leadership. ALTEX 2018, 35, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.J.; Grulke, C.M.; Edwards, J.; McEachran, A.D.; Mansouri, K.; Baker, N.C.; Patlewicz, G.; Shah, I.; Wambaugh, J.F.; Judson, R.S.; et al. The CompTox Chemistry Dashboard: A community data resource for environmental chemistry. J. Cheminform. 2017, 9, 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.T.; Dix, D.J.; Judson, R.S.; Kavlock, R.J.; Reif, D.M.; Richard, A.M.; Rotroff, D.M.; Romanov, S.; Medvedev, A.; Poltoratskaya, N.; et al. Impact of environmental chemicals on key transcription regulators and correlation to toxicity end points within EPA’s Tox Cast program. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2010, 23, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC. Some Chemicals Present in Industrial and Consumer Products, Food and Drinking-water. In IARC Monographys on the Evaluation of the Carcinogenic Risk to Human; IARC, WHO: Lyon, France, 2013; Volume 101, pp. 177–223. [Google Scholar]

- IARC. Re-evaluation of Some Organic Chemicals, Hydrazine and Hydrogen Peroxide. In IARC Monographys on the Evaluation of the Carcinogenic Risk to Human; IARC, WHO: Lyon, France, 1999; Volume 71, pp. 337–349. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya, M.; Toriba, A.; Onoda, Y.; Kizu, R.; Hayakawa, K. Evaluation of estrogenic activities of hydroxylated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in cigarette smoke condensate. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2005, 43, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.B.; Reiter, R.; Johnson, M.; Shah, M.S.; Iann, M.C.; Singh, B.; Richards, J.K.; Wang, A.; Stoica, A. Effects of tobacco smoke condensate on estrogen receptor-alpha gene expression and activity. Endocrinol 2007, 148, 4676–4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, M.D.; Finch, G.L. Diluted mainstream cigarette smoke condensates activate estrogen receptor and aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated gene transcription. Environ. Res. 1999, 80, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takamura-Enya, T.; Ishihara, J.; Tahara, S.; Goto, S.; Totsuka, Y.; Sugimura, T.; Wakabayashi, K. Analysis of estrogenic activity of foodstuffs and cigarette smoke condensates using a yeast estrogen screening method. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2003, 41, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.B.; O’Malley, B.W. Steroid receptor coactivators 1, 2, and 3: Critical regulators of nuclear receptor activity and steroid receptor modulator (SRM)-based cancer therapy. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2012, 348, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weikum, E.R.; Liu, X.; Ortlund, E.A. The nuclear receptor superfamily: A structural perspective. Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 1876–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenk, D.; Stresser, D.M.; McCants, J.C.; Nimrod, A.C.; Benson, W.H. Influence of beta-naphthoflavone and methoxychlor pretreatment on the biotransformation and estrogenic activity of methoxychlor in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1997, 145, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortenkamp, A. Low dose mixture effects of endocrine disrupters and their implications for regulatory thresholds in chemical risk assessment. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2014, 19, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, A.C.; Chappell, V.A.; Fenton, S.E.; Flaws, J.A.; Nadal, A.; Prins, G.S.; Toppari, J.; Zoeller, R.T. EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Endocr. Rev. 2015, 36, E1–E150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, S.S. Tobacco carcinogens, their biomarkers and tobacco-induced cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, H.; Yao, J. ERalpha, A Key Target for Cancer Therapy: A Review. Onco. Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 2183–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.C.; Lin, C.J.; Chen, P.Y.; Li, L.A. ERalpha-dependent estrogen-TNFalpha signaling crosstalk increases cisplatin tolerance and migration of lung adenocarcinoma cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2021, 1864, 194715–194729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Lin, C.J.; Hsieh, D.P.; Li, L.A. ERalpha phenotype, estrogen level, and benzo[a]pyrene exposure modulate tumor growth and metabolism of lung adenocarcinoma cells. Lung Cancer 2012, 75, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benowitz, N.L. Nicotine addiction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 2295–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanner, T.; Grimsrud, T.K. Nicotine: Carcinogenicity and Effects on Response to Cancer Treatment—A Review. Front. Oncol. 2015, 5, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarzynka, M.J.; Guo, P.; Bar-Joseph, I.; Hu, B.; Cheng, S.Y. Estradiol and nicotine exposure enhances A549 bronchioloalveolar carcinoma xenograft growth in mice through the stimulation of angiogenesis. Int. J. Oncol. 2006, 28, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaconji, I.B. Facts about nicotine toxicity. Arh. Hig. Rada. Toksikol. 2005, 56, 363–371. [Google Scholar]

- Health Council of the Netherlands: Committee on Updating of Occupational Exposure Limits. Nicotine; Health-Based Reassessment of Administrative Occupational Exposure Limits; Health Council of the Netherlands: Hague, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).