Abstract

Space weather science has been a growing field in Africa since 2007. This growth in infrastructure and human capital development has been accompanied by the deployment of ground-based observing infrastructure, most of which was donated by foreign institutions or installed and operated by foreign establishments. However, some of this equipment is no longer operational due to several factors, which are examined in this paper. It was observed that there are considerable gaps in ground-based space-weather-observing infrastructure in many African countries, a situation that hampers the data acquisition necessary for space weather research, hence limiting possible development of space weather products and services that could help address socio-economic challenges. This paper presents the current status of space weather science in Africa from the point of view of some key leaders in this field, focusing on infrastructure, situation, human capital development, and the research landscape.

1. Introduction

1.1. What Is Space Weather?

Space weather refers to the highly variable conditions in the geospace environment, including those on the sun, the interplanetary medium, and the magnetosphere-ionosphere-thermosphere system.

Space weather can have serious adverse effects on the advanced technology that our society depends on, such as satellite communications, Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) positioning, navigation and timing (PNT) services, and power grids, among others. The primary sources of space weather are solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs), both initiated by the Sun. Solar flares produce sudden bursts of radiation, while CMEs are associated with bursts of plasma, embedded with magnetic field structures, that travel in the solar wind before interacting with the Earth’s magnetosphere [1]. Energy and radiation from these events can harm astronauts, damage electronics on spacecraft, and impact GNSS precision, tracking, and acquisition. The geospace response to these changes includes impacts on the radiation belts, multiple large-scale and small-scale changes in the ionosphere, and the production of intense geomagnetically induced currents. To better mitigate space weather impacts on humanity and technological systems, there is a recognized need for improved forecasts, better environmental specifications, and more durable infrastructure. Improved monitoring and modelling of space weather has been identified as critical for the better protection of infrastructure and national economies during periods of large space weather events.

Understanding space weather is of great importance for awareness and avoidance of the consequences attached to space weather events either by system design or by efficient warning and prediction systems. Providing timely and accurate space weather information, nowcasts and forecasts are possible only if sufficient observation data are continuously available. Based on a thorough analysis of current conditions, comparing these conditions to past situations, and using numerical models similar to terrestrial weather models, forecasters can predict space weather on time scales of hours to weeks.

1.2. The African Context

The African Union (AU) has identified space science and technology as a key enabler of Africa’s Agenda 2063 and created an African Space Agency (AfSA). The long-term goal of the agency is to enable Africa to leverage technologies developed in the space sector to address societal challenges, in addition to opening up new frontiers of space applications that could be a basis for the establishment of industries that would provide job opportunities for the many unemployed youths in Africa.

Space weather science, in particular, is one of the areas under active consideration by the AU partly due to growing interest in the acquisition and deployment of satellites in space and also the requirement by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) for the provision of space weather services to the aviation industry across the world [2]. Space weather science has been a growing field in Africa since 2007, the year of the International Heliophysical Year (IHY 2007), during which time deployment in Africa of most ground-based observing infrastructure commenced. The deployment of ground-based observing infrastructure was rolled out through collaborations between African universities and their counterparts, mostly American institutions (such as Boston College, United States Airforce Research Laboratories (AFRL), Stanford University), and Kyushu University (Japan), among others. The deployments have often been accompanied by workshops aimed at African university lecturers and their students, with a focus on data acquisition, data processing, and interpretation. The training workshops, which continue to be held at least once a year, are run jointly through partnerships of the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) and Boston College. Supplementing these efforts is the training provided by the Scientific Committee on Solar-Terrestrial Physics (SCOSTEP).

However, despite these efforts, there are still considerable gaps in ground-based space-weather-observing infrastructure in African regions/countries. This hampers the data acquisition necessary for space weather research, hence limiting the provision of products and services that could help address socio-economic challenges. Due to the growing investment in space activities in Africa, including the building of nano-satellites/cubesats and the purchase and deployment of off-the-shelf satellites, there is a growing need for Africa to develop a critical mass of expertise to help mitigate space weather effects on critical space-based and ground-based technological infrastructure. Space weather effects could be felt in the aviation industry, power grid, land/sea and air navigation, and high-frequency communications, among other technological systems. Evidence of space weather’s impact in Africa includes South Africa’s space-weather-induced loss of its homemade SumbadilaSat satellite in September 2011 and of several high-voltage power transformers following the impacts of the Halloween storm of October 2003 on power systems through geomagnetically induced currents [3]. These events created awareness in Africa about the realities of space weather’s impact on investments in the space sector and power sector, and they also brought to the fore the need for thorough space weather modelling and forecasting to prepare Africa to mitigate the consequences of space weather impacts on technologies.

Space weather preparedness is important not only for Africa but indeed the rest of the world. Space weather preparedness is underpinned by three elements: designing mitigation into infrastructure where possible; developing the ability to provide alerts and warnings of space weather and its potential impacts; and having in place plans to respond to severe events. This kind of preparedness calls for high-level research and national and international coordination.

This paper provides information on space weather infrastructure, human capital development, research achievements, ongoing and upcoming projects, international collaborations, funding sources, gaps in infrastructure, and human resources, as well as suggestions on what needs to be done going into the future.

This paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, we present the distribution of space weather infrastructure in Africa and discuss data accessibility and reliability; Section 3 deals with human capital development (HCD), completed and on-going postgraduate research, and various HCD initiatives; Section 4 gives insight into gaps in infrastructure and current and planned space weather projects; and in Section 5, we give the conclusion and way forward.

2. Distribution of Space Weather Infrastructure in Africa

The information captured in this paper was obtained using desktop research; information from individual and institutional equipment hosts in various countries who also participated in authoring this paper; internet sources; reports; and other publications that are publicly available.

2.1. Space Weather Monitoring

In monitoring space weather, ground-based instruments and satellites are used to monitor the Sun for any changes and issue warnings and alerts for hazardous space weather events.

Solar activities, such as solar flares, coronal mass ejection, and moon shadow of an eclipse, induce the rapid change of ionosphere morphology, so-called ionospheric weather, which significantly impacts radio communication and navigation systems. Ground-based GNSS receivers can measure the ionospheric total electron content (TEC) and the ionospheric electron density (through ionospheric tomography). This tool allows continuous monitoring of ionospheric weather and modelling of ionospheric climate. Magnetometers make it possible to follow the regular variations of electric currents in the ionosphere and magnetosphere caused by solar wind dynamics. During magnetic storms, the magnetic variations are affected by the disturbance of ionospheric and magnetospheric currents generated by solar events. Thus, GNSS receivers and magnetometers are very useful in monitoring the impact of solar disturbances on the Earth’s environment and in the development of space weather science in Africa.

Many other instruments are used for space weather monitoring, including very-high-frequency (VHF) and very-low-frequency (VLF) receivers, ionosondes, incoherent scatter radar, all-sky cameras, and Fabret–Perot interferometers, among others. Some of these are discussed below.

2.1.1. Global Navigation Satellite Systems Receivers

GNSS has been used in all forms of transportation: space stations, aviation, maritime, rail, road, and mass transit. PNT plays a critical role in telecommunications, land surveying, law enforcement, emergency response, precision agriculture, mining, finance, scientific research, and so on. Space weather is one of the major limiting factors for the precision and reliability of PNT services from GNSS. Geomagnetic storms and substorms, solar flares, and ionospheric irregularities can result in PNT deterioration.

Since the ionosphere is a very dynamic medium and due to its dispersive nature, dual-frequency GNSS measurements may effectively be used to derive robust and accurate information about the ionospheric state under quiet and perturbed space weather conditions. Ground-based measurements enable mapping of the total ionization of the ionosphere (i.e., TEC). The hosts of most of the equipment installed for space weather research have a free data policy for research purposes, so the accessibility of data via the internet is not a challenge.

- (a)

- GNSS Receivers for Ionospheric Scintillation Monitoring

Most of the dedicated high-rate GNSS receivers required for GNSS ionospheric scintillation and TEC monitoring (GISTM) were donated by US Air Force Research Laboratories (AFRL) and Boston College [4]. The deployments took place mostly between the years 2007 and 2014.

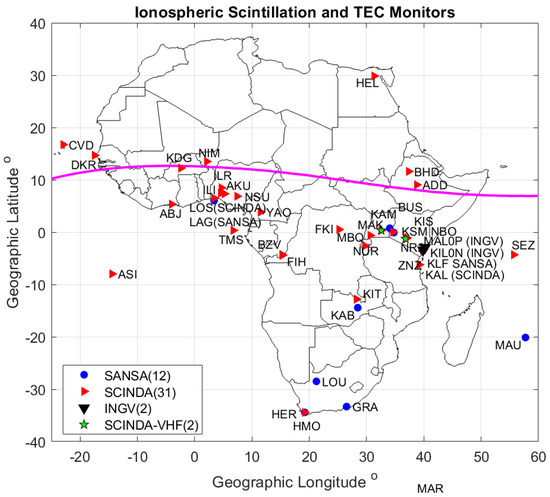

These instruments are primarily used for L-band monitoring of scintillations on GNSS signals traversing through the ionosphere. Figure 1 and Table 1 below show the distribution of GNSS ionospheric scintillation receivers across the continent. The map in Figure 1 shows a limited number of GISTMs in North and Southern Africa, which are mid-latitude regions with a low incidence of ionospheric scintillation. East Africa stands out as the area with the largest number of instruments for GISTM, followed by West Africa [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. The line running from the geographic longitude 10° to the east in Figure 1, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5, is the geomagnetic meridian.

Figure 1.

Distribution of GPS ionospheric scintillation and TEC monitors (GISTM) deployed by Boston College (USA) and US Air Force Research Laboratories in Africa (SCINDA 2007–2014) and by the South African National Space Agency (SANSA). The line running from the geographic longitude 10° is the geomagnetic meridian.

Table 1.

GPS ionospheric scintillation and TEC monitors in Africa.

The USA equipment donors (SCINDA) and their collaborators deployed most of the instruments in Central Africa, which is the region with the highest incidence of ionospheric scintillation. Due to problems with maintenance, power, security, and internet access, there is a considerable gap in the currently operating ionospheric scintillation monitoring infrastructure in large parts of Africa. The GISTM stations and their host countries are listed in Table 1.

Other than the above-listed stations, the South African National Space Agency (SANSA) also operates Novatel GSV4004B scintillation receivers at several other locations in South Africa and on nearby islands, namely at Louisvale (28.49° S, 21.23° E), Grahamstown (33.32° S, 26.5° E), Gough Island, (40.34° S, 9.88° W), and Marion Island (46.87° S, 37.85° E). Since 2017, SANSA has installed Novatel GPStation6 and Septentrio PolaRx5S multi-constellation GNSS scintillation receivers for real-time data streaming from each of the following locations in Africa: Kilifi (Kenya, 3.62° S, 39.84° E) [15], Kabwe (Zambia, 28.46° N, 14.44° E), Lagos (Nigeria, 6.52° N, 3.38° E), and Busitema (Uganda 0.75° N, 34.04° E). SANSA is currently working on the deployment of a few more such receivers in Central and East Africa (Gaborone in Botswana, Tororo in Uganda, and Bahir Dar in Ethiopia) to provide essential real-time data to the Regional Space Weather Warning Centre of the International Space Environment Service (ISES) at the South African National Space Agency in Hermanus.

In 2019, the Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV) started the installation of new GNSS receivers for scintillation monitoring covering both East and West Africa. At present, three receivers in Kilifi (Kenya, 3.62° S, 39.84° E), Malindi (Kenya, 2.93° S, 40.21° E), and Abuja (9.07° N, 7.49° E) are operational, making their data available in real-time.

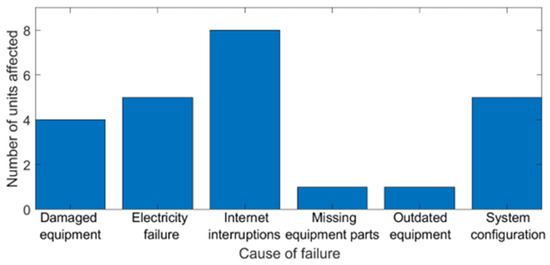

Almost 50% of installed SCINDA GISTMs in Africa are non-operational. This state of affairs is not suitable for space weather research in Africa. The reasons for this are damage, intermittent electricity supply, and poor internet connectivity, thus prohibiting data transfer to the central server in Boston College; missing equipment parts; equipment reaching the end of its useful operational lifetime; and system configuration problems (see Figure 2). This means mitigating space weather effects is not possible in large swathes of Africa due to the infrastructure gaps and the non-operational status of most receivers. Consequently, space weather advisories to various sectors would only be possible in certain parts of Africa but not in others. This is particularly bad for the aviation industry since the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) now requires all airports to integrate space weather information in their aeronautical information services [16]. This state of the GISTMs in Africa hampers space weather research in the continent and jeopardizes networking and collaborations. In addition, it highlights the lack of goodwill by the hosts to avail funds to replace damaged equipment or even add more to the network to enable research work to continue.

Figure 2.

The causes of the non-operational status of SCINDA GISTM stations and the number of stations affected by each of these causes.

Figure 2 clearly shows that most of the GPS receiver stations are unable to transmit data to external collaborators because of poor internet connectivity, followed by unreliable electricity supply, and lack of technical expertise to configure the receiver systems properly. These equipment hosts often need thorough training to be able to run and maintain the equipment, but usually, this is at the cost of the external collaborator. For operational stations, not all operate optimally (i.e., some GPS receiver stations operate intermittently, a few are fully operational, and the vast majority are non-operational).

- (b)

- Geodetic GNSS Receivers and GNSS reference receivers for surveying and mapping.

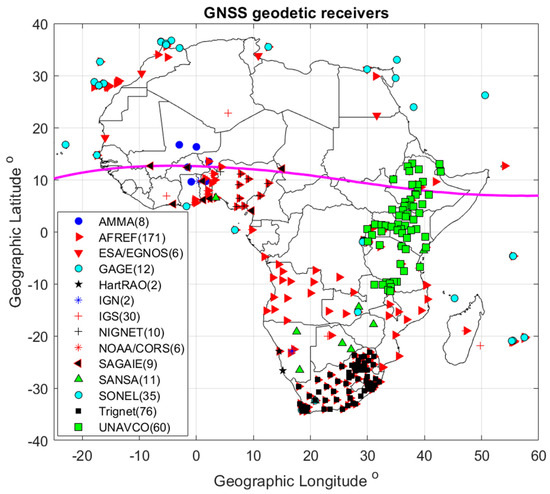

GNSS receivers have been deployed by several external parties (NASA, NOAA, ESA, BKG, and others) for geodetic studies of the African continent. Besides the GNSS receivers deployed by external parties, national mapping agencies in many African countries have installed GNSS reference receivers to support mapping and surveying work. Figure 3 shows the distribution of GNSS geodetic and reference receivers in and around Africa.

Figure 3.

GNSS geodetic and reference receiver distribution. The purple line shows the location of the geomagnetic equator.

(b1) International Global Navigation Satellite Systems Service (IGS).

The IGS is a voluntary federation of many worldwide agencies (350) that pool resources and data from permanent GNSS stations (512 in 2023) to generate precise GNSS products. The International GNSS Service provides, on an openly available basis, the highest-quality GNSS data, products, and services in support of the terrestrial reference frame; Earth observation and research; PNT; and other applications that benefit science and society [17].

Out of a total of 118 countries around the world, only 22 countries in Africa participate in this network. The list of the 30 operational stations in 2023 is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

IGS GNSS stations operating in 2023.

The measurements from 1994 are available on two websites in the United States, NASA’s CDDIS and SOPAC [2,18], and on regional sites (IGN in France [19] and BKG in Germany [20]).

- (c)

- GAGE/UNAVCO Network

The Geodetic Facility for the Advancement of Geoscience (GAGE, formerly UNAVCO, University NAVSTAR Consortium) is a non-profit university-governed consortium funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). It provides technical support to scientists for geodesy, tectonic, and geophysical events and education. It is responsible for archiving and disseminating measurements in RINEX format. The main projects are for North America and the poles. However, for more than 20 years, UNAVCO has supported a project covering the African continent (‘AfricaArray’), with the installation of many GNSS receivers mainly around the East African Rift for a few months up to several years, which can be used for space weather research (Figure 4). The files are available on their site via ftp or web GUI [21].

Figure 4.

Locations of magnetometers of various networks in Africa. The purple line shows the location of the geomagnetic equator.

- (d)

- The African Geodetic Reference Frame (AFREF)

The African Geodetic Reference Frame (AFREF) was conceived as a unified geodetic reference frame for Africa and as the fundamental basis for national and regional three-dimensional reference networks that are entirely consistent and homogeneous with the International Terrestrial Reference Frame (ITRF). Continuously Operating Reference Stations (CORS) or GNSS base stations were established to achieve this. The AFREF operational data center collects data daily. The data from all the stations of the IGS and GAGE networks are freely available on this website [22].

- (e)

- The TRIGNET Network

The geodetic GNSS reference receivers of the TRIGNET network in South Africa are deployed and maintained by the South African Chief Directorate: National Geospatial Information (CD:NGI). This network of more than 60 GNSS receivers has provided South Africa with better GNSS infrastructure than the rest of the African countries. Data from the TRIGNET network is available via the web link of the Chief Directorate: National Geospatial Information (CD:NGI) [23].

SANSA (South African National Space Agency) recently deployed multi-constellation geodetic GNSS receivers for real-time ionospheric monitoring in South Africa (SUTG, 32.37° S, 20.81° E), in Southern Botswana (PALP, 22.60° S, 27.13° E; and LETL, 21.42° S, 25.57° E), in Zimbabwe (HARG, 17.78° S, 31.05° E), in Namibia (KMHG, 26.53° S, 18.1° E) and in Lagos, Nigeria (TSUG, 19.20° S,17.58° E).

- (f)

- African Monsoon Multidisciplinary Analysis (AMMA) GPS Network [24]

The AMMA GNSS receivers were installed in Djougou (Benin), Niamey (Niger), Gao (Mali), Tamale (Ghana), Ouagadougou (Burkina-Faso), and Tombouctou (Mali) during the period 2006–2009. Although the data can be used across disciplines, these GNSS stations were established for meteorological applications, but the data can also be used for space weather studies and can be downloaded from the AFREF website.

- (g)

- The CNES/SAGAIE network

CNES (France) began the implementation of the SAGAIE (Stations ASECNA GNSS pour l’Analyse de la Ionosphère Equatoriale) network in 2013 for the real-time correction of an extension of SBAS/EGNOS to Africa. The current network includes nine stations (Table 3), all installed at major airports, often with one geodesy receiver and one scintillator receiver at each station. Operational monitoring is carried out by ASECNA (Agence pour la Sécurité de la Navigation aérienne en Afrique et à Madagascar). Unfortunately, these data are not yet freely accessible [25].

Table 3.

CNES/SAGAIE stations operating in 2023.

- (h)

- The SONEL network

SONEL (Système d’observation du Niveau des eaux Littorales) produces accurate sea level measurements from tide gauges and geodetic receivers. There are more than 1000 GNSS stations near the coasts around the world, but only a few dozen around the African continent. The measurements are available on their website [26].

- (i)

- CORS and Private Networks

There are many CORS networks in several African countries. Unfortunately, their advertising is limited, so it is very difficult to establish a list of operational stations in each. Those responsible do not offer web links, and the measurements taken are unfortunately inaccessible. Two exceptions can be cited:

The NOAA/CORS network in Benin included 7 stations (BJKA, BJNA, BJNI, BJPA, BJSA, BJAB, BJCO). The network was shut down in January 2020.

The NIGNET network (Nigerian GNSS Reference Network) in Nigeria. It included up to 14 stations distributed in each region (BKFP, HUKP, MDGR, RECT, FPNO, ABUZ, CGGT, FUTY, OSGF, ULAG, UNEC, RUST, CLBR, GEMB). The measurements were used for geodesy, troposphere, and ionosphere. The network was shut down in 2017. The data of these two networks are available on the AFREF website.

- (j)

- OMNISTAR Differential GNSS

OmniSTAR provides GNSS receivers for their space-based GNSS correction services that can improve the accuracy of precise positioning applications. The OMNISTAR (Trimble Private Network) GPS receivers are mainly deployed along the African coast to improve the accuracy of GPS positioning for ocean navigation, but they are still useful for space weather studies. OMNISTAR is a private commercial network of satellite-based augmentation services. The data from this network are not freely available [27].

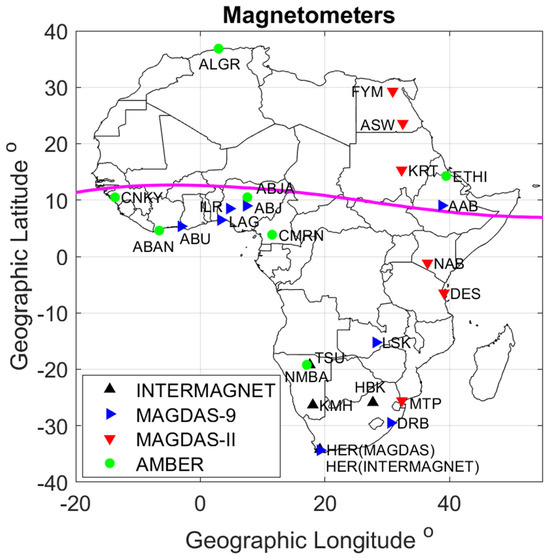

2.1.2. Magnetometers in Africa

Magnetometers are ground-based infrastructure used in space weather monitoring for monitoring the impact of geomagnetic storms. Figure 4 and Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 provide the locations and other details of the magnetometers in Africa.

Table 4.

AMBER magnetometer stations in Africa.

Table 5.

AMBER network host institutions and contact persons.

Table 6.

Magnetometers installed in Africa by Kyushu University, Japan. The geomagnetic dipole coordinates are determined using model calculations provided by the British Geological Survey—Geomagnetism (https://www.bgs.ac.uk/?s=coordinate+calculator, accessed on 26 November 2023) The geomagnetic coordinates and the dip latitude were calculated using the BGS online IGRF model (https://geomag.bgs.ac.uk/data_service/models_compass/igrf_calc.html, accessed on 26 November 2023).

Table 7.

MAGDAS magnetometer station host countries and their universities.

- (a)

- AMBER Magnetometers [28,29,30,31]

The African Meridian B-field Education and Research (AMBER) magnetometer network is operated by Boston College and funded by NASA and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR). The principal investigators are Endawoke Yizengaw, PhD. (Ethiopia), Boston College, USA and Mark Moldwin, PhD, University of Michigan, USA (http://magnetometers.bc.edu/index.php/amber2, accessed on 26 November 2023). The AMBER stations in Africa are Adigrat (Ethiopia), Medea (Algeria), Yaounde (Cameroon), Tsumeb (Namibia), Abuja (Nigeria), Conakry (Guinea), and Abidjan (Ivory Coast).

- (b)

- Magnetic Data Acquisition System (MAGDAS) stations in Africa [32,33,34,35,36,37,38]

The principal investigator (PI) of the project which installed these magnetometers was Prof. Kiyohumi Yumoto (deceased) of the International Center for Space Weather Science and Education (ICSWSE), Kyushu University, Japan. ICSWSE, Kyushu University, is one of the few research institutes/universities conducting research and education in space weather in the world. The MAGDAS network has over seventy fluxgate magnetometers distributed across the world, with 14 of them installed in Africa. The MADGAS data have been used by several researchers in Africa for space weather research, but quite a number of these magnetometers are no longer operational.

The African countries and their respective universities hosting the magnetometers are listed in Table 7.

Most of these facilities are hosted by departments of physics and a few by the electrical engineering departments in the respective universities. Ensuring the continuity of operations of the magnetometers has been a challenge since the funding stream from Japan dried up after the demise of the PI.

- (c)

- INTERMAGNET

INTERMAGNET is a global network of observatories dedicated to monitoring geomagnetic field variations across the world. There are INTERMAGNET magnetometers in five countries in Africa, namely Ethiopia, Madagascar, South Africa, Algeria, and Senegal. Details of the four INTERMAGNET observatories and other magnetometers in Southern Africa can be found in [16,39,40,41,42]. At each of the four INTERMAGNET observatories in Southern Africa, there are several types of magnetometers, including Overhauser Scalar Magnetometer GSM-90, 3-axis Fluxgate Magnetometers DMI FGE, and 3-axis Fluxgate Magnetometers LEMI025.

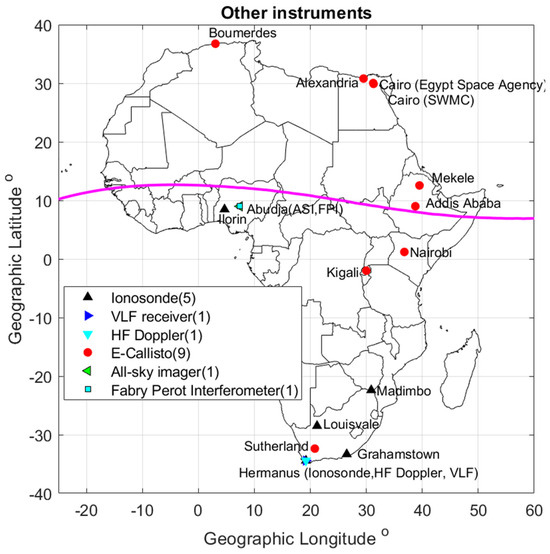

2.1.3. Other Ground-Based Facilities

Several other ground-based facilities that can be used for space weather monitoring have been deployed in Africa. Figure 5 depicts the distribution of most of the other space weather equipment in Africa.

Figure 5.

Distribution of other infrastructure dedicated to space weather monitoring in Africa.

- (a)

- Incoherent Scatter Radars

The incoherent scatter radar (ISR) is one of the most powerful sounding methods developed to estimate certain properties of the ionosphere. This radar system determines the plasma parameters by sending powerful electromagnetic pulses to the ionosphere and analyzing the received backscatter. This analysis provides information about parameters such as electron and ion temperatures, electron densities, ion composition, and ion drift velocities. Nevertheless, in some cases, ISR analysis has ambiguities in the determination of plasma characteristics. They are in Ethiopia and Nigeria. There is also one under construction in Kenya.

- (b)

- Ionosondes

The ionosondes are used to generate ionograms and assist in determining the state of the ionosphere and selecting the optimum frequencies for HF radio communication.

The ionosondes are installed in South Africa (four), Kenya (one), Ethiopia (one), and Nigeria (one). The stations in Kenya, Ethiopia, and Nigeria are non-operational. In the Ethiopian case, the electric power supply is unreliable and unstable, and in the Kenyan case, there are issues with system configuration as well as storage of data. Only two of the ionosondes in South Africa are currently operational (HR, GR), while the two others are being refurbished after vandalism and theft.

A new ionosonde was installed in July 2023 in Malindi, Kenya, at the Broglio Space Center (BSC) managed by the Italian Space Agency and it is the only one operational, at present, outside South Africa.

- (c)

- Very-Low-Frequency (VLF) and Very-High-Frequency (VHF) receivers

Several VLF devices have been distributed by Stanford University (USA) and installed in several African countries (See Table 8) to monitor the lower layer of the ionosphere (D layer). They are divided into two groups: those related to the AWESOME (Atmospheric Weather Education System for Observation and Modeling of Effects) network and those related to the SID (Sudden Ionospheric Disturbance Monitor) and super-SID receivers. Besides these, there is also the Compact Astronomical Low-Cost Low-Frequency Instrument for Spectroscopy and Transportable Observatory (CALLISTO) spectrometer [43,44], which operates between 45 to 870 MHz. The monitors are installed in Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda, Egypt, Algeria, and South Africa. The principal investigator of CALLISTO is Christian Monstein of the Radio Astronomy Group (RAG) at ETH Zurich, Switzerland. SANSA operates an e-Callisto Solar Radio Spectrometer (http://e-callisto.org/) at Sutherland in South Africa (Lat 32:38° S, Lon 20:81° E). Table 8 gives some details of the VLF and VHF receivers installed in Africa.

Table 8.

The number of VLF and VHF receivers installed.

Some VHF monitors [11] were installed across the continent by AFRL. The host countries are Congo (Brazzaville), Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, and Uganda.

Most of North Africa and parts of Central Africa have substantial infrastructure gaps. Several countries in these regions are politically unstable, thus making the installation of ground-based space weather equipment rather difficult. These gaps will need to be filled so that there will be sufficient data to enable adequate coverage of Africa in terms of space weather research.

2.2. Data Access and Reliability

Most of the data generated by the observing equipment have a free access policy, except for those owned by national mapping agencies in various countries. However, different data providers have imposed conditions to be met before granting access to the data. In most cases, if the data is purely for research, and not for commercial use, then free access is always granted, but some acknowledgement of the data source is required whenever a publication is produced with them. The SANDIMS data portal at SANSA [45] provides free access, via a data request for research applications, to all geomagnetic, ionospheric, and magnetospheric data gathered from SANSA Space Science’s instrumentation network. The eSWua web portal of Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV) in Italy [46] provides free access to visualization and downloads of the data from instruments managed by INGV. The users can access data from a GUI or a service from which massive data downloading can be performed automatically.

This open data policy has enabled many African researchers to benefit from space weather data generated by equipment hosted in the continent and beyond. In effect, this has contributed immensely to human capital development in space weather science in many countries in Africa. However, a major setback is the non-operational status of most of the equipment due to several factors such as non-stable electric power supply, poor internet connectivity, poor system configuration, poor maintenance, and equipment operating beyond its useful lifetime. Replacement of ageing equipment and maintenance issues are made worse by the fact that some African equipment hosts do not actually use the data for any training or research and hence have no interest in maintaining or replacing the equipment. Although some of the factors limiting successful equipment functioning could be addressed by the hosts (e.g., unreliable electric power by investing in solar power), most of the equipment hosts do not have funding for this, and most of the host institutions do not provide support towards that end.

The lack of a good network of space weather monitors in Africa is limiting the modelling of the African sector of the near-earth space environment and thus the development of space weather products and services. For example, it is known that scintillation threatens the performances of GNSS-reliant services requiring high-precision positioning, but forecasting scintillation is still a challenge. The development of ionospheric climatology over various geographic regions of Africa would be a useful step in providing space weather information. Climatology is only possible with a proper network of space weather monitors that continuously provide data over an extended period.

2.3. Space Weather Products and Services

There is a need to develop thresholds of space weather threats on a variety of technological systems in Africa. This includes the aviation industry since ICAO now recommends the provision of space weather alerts as part of regulations and standards for enhanced safety in civil aviation. Except for SANSA Space Science in South Africa, the rest of Africa has not developed space weather products and services for the aviation industry and other industrial sectors. Commercialization of space weather research findings will help mitigate economic losses brought about by space weather events, and it could also possibly provide funding streams to support space weather research. At the moment, there is a huge disconnect between industry and academia in Africa.

3. Human Capital Development

The training and research in space weather in various African countries are at different levels. We provide a detailed summary of the human resource situation in selected countries below.

3.1. Capacity Building

Activities geared towards human capital development are given in Table 9. These include training workshops and doctoral studies in some countries in Africa as of the end of 2022. Table 9 also gives a list of the universities involved.

Table 9.

Capacity building by African scientists.

Efforts by the United Nations Basic Space Science Initiative (UNBSSI) since the year 1991 have led to an increase in space weather capacity building. For example, there were 10 PhD theses defended during the first decade (1991–2001), while 84 PhD theses were defended during the period 2001–2023. Presently, there are 68 PhD theses in progress.

3.2. International Achievements [47,48]

Since 2014, many African space weather researchers have obtained international awards for exemplary research in space weather (Table 10).

Table 10.

Awards.

Thus, capacity building in this field is growing, and the quality of African space weather researchers is comparable to the rest of the world. This is exemplified by the number of recipients of international awards coming from Africa, and also by the sheer number of those graduating with PhDs or with PhDs in progress.

3.3. Initiatives by Professional Societies/International Organizations

Some selected initiatives in support of space weather research in Africa are mentioned here.

- (a)

- African Geophysical Society

The African Geophysical Society (AGS) is a dynamic, innovative, and interdisciplinary scientific association committed to the pursuit of understanding Earth and space for the benefit of mankind. The objectives of the AGS are to expand and strengthen the study in the African continent of the Earth and other planets, including their environments. The main goals are to facilitate cooperation among scientists; create national, regional, and international scientific organizations involved in geophysical and other related research and intiating new research and training programs; and popularize various geophysical research and training programs via scientific conferences, publications, and training in both the short and long terms.

The AGS has brought together African researchers and created platforms for collaborative research, co-supervision of students, and external examination of theses/dissertations. This has greatly improved the space weather research landscape in Africa.

- (b)

- URSI Commission G Working group: “Capacity building and training”

During the International Radio Science Union (URSI) General Assembly 2021, held in Rome from 28 August to 4 September, a new working group (WG) in the framework of Commission G (Ionospheric Radio and Propagation) has been established. This WG, named “Capacity Building and Training,” is chaired by C. Cesaroni (INGV, Italy) and co-chaired by J. Olwendo (PU, Kenya), B. Nava (ICTP, Italy), and P. Doherty (now deceased; BC, USA). The “Capacity Building and Training” working group deals with activities related to the training of students and young scientists mainly from developing countries. The main objectives of the working group are: to rganize international workshops, especially for young scientists from developing countries; to facilitate visits/exchanges for young scientists by putting in place actions for fundraising; and to organize periodical webinars for sharing new research among the commission G community members. This group is championing the aspirations of the African space weather research community.

- (c)

- Scientific Committee on Solar-Terrestrial Physics (SCOSTEP)

Many African master’s and doctoral researchers have benefited from the SCOSTEP visiting scholar program, whereby a scholar is sponsored to undertake his/her study in another institute to access facilities and expertise that are not available at their home institute. This has provided excellent opportunities for networking and co-authorship of research articles.

- (d)

- The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics/Boston College/INGV

Every year since 2009, the ICTP and Boston College have been organizing training workshops on GNSS and space weather for developing countries. Recently, INGV has been contributing by organizing additional workshops in collaboration with the aforementioned institutions. Many African lecturers and students have been trained in space weather monitoring equipment installation and maintenance and data acquisition, reduction, and interpretation. Some of these works have been organized in Africa and have greatly impacted space weather research capacity in Africa.

- (e)

- Groupe de Recherche en Géophysique Europe Afrique (GIRGEA) network [49,50,51,52,53]

In the framework of the UNBSSI program, the GIRGEA network organized has schools on space weather since 1995. Since 2013, the GIRGEA scientific network has been organizing regional schools every two years.

3.4. International Collaborations

Space weather training in Africa has been built on two models, namely:

- (a)

- Training of trainers and their students: The first cohort of African lecturers who were converted from their fields of research to space weather research were made hosts of space weather equipment. The equipment hosts were then trained to archive and use the data produced for research. The pioneering students who used the data for their postgraduate research were jointly supervised by their home-based academic staff and equipment donors. This model has enabled Africans to do research at their home institutions where they were/are registered as students while also building international networks and collaborations. The model forestalled potential brain drain.

- (b)

- Intra-Africa co-supervision of postgraduate research: Many African students are given research topics by their African senior researchers who co-supervise them and also host them for research visits whenever possible.

The weak link in these two models is the lack of investment by the researchers’ home institutions in space weather infrastructure development.

3.5. Funding Sources

Space weather research in Africa has been supported through a variety of funding streams. These include:

- (a)

- External financing: Most of the space weather capacity building has been supported through external funding, especially for the acquisition and installation of research equipment, but local African universities have often provided their students with the necessary facilitation to enable them to undertake their research work. More often than not, the facilitation has been in terms of tuition fee waivers and in-kind support.

- (b)

- Government: Some national space agencies and research councils/agencies are now funding space weather research and training workshops to build a critical mass of expertise within the shortest time possible.

- (c)

- Industry: A few industry stakeholders, like the aviation industry and electric power distribution companies, in some few African countries have also come on board to support space weather research, although their involvement is still at a very low level. The challenge here has been that the industry players are not aware of the relevance of space weather research to their businesses. This calls for more awareness campaigns to enlighten the industry, and thus possibly attract more funding from the sector.

4. Gaps in Infrastructure and Human Resources

Gaps

There are many countries in Africa where space weather research is non-existent or infrastructure for space weather monitoring is lacking. In some cases, institutions in some African countries may be hosting facilities whose data they do not use at all, and hence they take little interest in ensuring the functionality of the facilities. This situation is equivalent to cases where there are no facilities installed at all because the result is the same, namely, there is no data to facilitate research.

Gaps in infrastructure are evident in regions like Chad, Central African Republic, Somalia, Eritrea, and South Sudan. Incidentally, these countries lie on or very close to the geomagnetic equator, where ionospheric conditions are very dynamic and have potentially adverse consequences for the technological systems in use. This lack of ground-based observing facilities makes the understanding of space weather dynamics over Africa difficult. Non-deployment of space weather monitors may have been occasioned by political instability in those countries. In some other countries, the infrastructure exists but is not operating optimally due to erratic electric power supply, low internet bandwidths, poor maintenance, or lack of funds to replace ageing or obsolete monitors. Another aspect of the gaps observed is the non-uniform spread of different types of monitors across the continent. The reason for this is partly because collaborators would normally deploy their facilities where they already have points of contact or in a region of interest depending on the relevant space weather campaign at that time. This aspect informs the observed trends in the distribution of equipment across Africa.

The gaps in infrastructure also go hand in hand with the lack of or inadequate human resources in many countries. Many countries do not have well-established departments of physics where space weather research could thrive. This badly limits postgraduate research in space weather. However, despite the gaps in the deployment of monitors, some current and upcoming projects will help improve the situation (see Table 11). This table may not be exhaustive, but it indicates that more facilities are coming to Africa.

Table 11.

Completed, current, and upcoming projects in space science/space weather in Africa.

5. Conclusions and the Way Forward

In conclusion, we have gathered that:

- (a)

- There is a huge infrastructure gap, so more instruments need to be deployed for space weather monitoring in Africa to fill in the gaps. This should not be left entirely to outsiders. There is a need for more African institutions/governments to invest in space weather research. To a small extent, this already happening, especially as an initiative by some space agencies in Africa, and perhaps the newly established African Space Agency should play a more proactive role in this.

- (b)

- The community of space weather researchers in Africa is growing in number and competence, and this should encourage collaborations with other researchers from outside the continent. African and other researchers should team up and run more joint research projects, write proposals for funding, and carry out joint supervision of students.

- (c)

- There is a need to develop thresholds of space weather threats on a variety of technological systems in Africa to inform space weather services in Africa.

- (d)

- There is a need to create more awareness among the potential commercial stakeholders whose infrastructures and businesses could be impacted by space weather so that they put in place measures to mitigate space weather impacts. This could be one avenue for attracting the funding needed for research and development.

- (e)

- We recommend that the African Space Agency (AfSA), when it becomes operational, takes up the challenge of improving space weather research infrastructure in the continent.

- (f)

- Finally, it is well known that space weather prediction can only be possible by fully understanding the complex interactions and coupling occurring between the upper and the lower atmosphere, including the troposphere level. In this regard, the African continent offers a unique opportunity to have a global view as it is mostly composed of land areas spanning the northern mid-latitudes to the southern mid-latitudes. For this reason, the installation of different pieces of space-weather-monitoring equipment in Africa will have important and priceless benefits for the space weather field as a whole.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: P.B. and C.A.-M.; Methodology: P.B., C.A.-M. and P.J.C.; software for plotting of figures: P.B. and P.J.C.; validation: P.B., C.A.-M., R.F. and P.J.C.; formal analysis: P.B., P.J.C., R.F., C.A.-M., C.C. and H.M.; investigation: all the authors were involved; resources: All the authors contributed information used in the research; data curation: P.B., P.J.C., C.A.-M., C.C. and H.M.; writing—original draft preparation: P.B. and C.A.-M.; writing—review and editing: P.B., P.J.C., R.F. and C.A.-M.; visualization: P.J.C.; supervision: C.A.-M.; project administration: P.B. and C.A.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Knipp, D.D. Understanding Space Weather and the Physics Behind It; The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 13-978-0-07-340890-3. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://cddis.nasa.gov/Data_and_Derived_Products/GNSS/GNSS_data_and_product_archive.html (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Gaunt, C.T.; Coetzee, G. Transformer failures in regions incorrectly considered to have low GIC-risk. In Proceedings of the IEEE Lausanne Power Tech Conference, Lausanne, Switzerland, 1–5 July 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Scientific Research, Boston College, USA. Available online: https://www.bc.edu/content/bc-web/research/sites/institute-for-scientific-research/research/space-weather.html (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Akala, A.O.; Amaeshi, L.I.N.; Somoye, E.O.; Idolor, R.O.; Okoro, E.; Doherty, P.H.; Groves, K.M.; Bridgewood, C.T.; Baki, P.; D’Ujanga, F.M.; et al. Climatology of GPS Scintillations Over Equatorial Africa during the minimum and Ascending Phases of Solar Cycle 24. Astrophys. Space Sci. 2019, 17, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omondi, G.E.; Baki, P.; Ndinya, B.O. Total electron content and scintillations over Maseno, Kenya, during high solar activity year. Acta Geophys. 2019, 67, 1661–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paznukhov, V.V.; Carrano, C.S.; Doherty, P.H.; Groves, K.M.; Caton, R.G.; Valladares, C.E.; Seemala, G.K.; Bridgwood, C.T.; Adeniyi, J.J.; Amaeshi, L.L.; et al. Equatorial plasma bubbles and L-band scintillations in Africa during solar minimum. Annales Geophys. 2012, 30, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olwendo, O.J.; Baki, P.; Mito, C.; Doherty, P. Elimination of Superimposed Multipath effects on Scintillation Index on Solar Quiet Ionosphere at Low latitude using a single SCINDA-GPS receiver. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS 2010), Portland, OR, USA, 21–24 September 2010; pp. 386–392. [Google Scholar]

- Olwendo, O.J.; Baki, P.; Cilliers, P.J.; Mito, C. Using GPS-SCINDA Observations to study the correlation between Scintillation, Total Electron Content Enhancement and Depletions over the Kenyan Region. Adv. Space Res. 2012, 49, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ujanga, F.M.; Baki, P.; Olwendo, O.J.; Twinamasiko, B.F. Total Electron Content of the Ionosphere at two stations in East Africa during the 24–25 October 2011 Geomagnetic storm. Adv. Space Res. 2013, 51, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olwendo, J.; Baluku, T.; Baki, P.; Cilliers, P.J.; Mito, C.; Doherty, P. Low Latitude Ionospheric Scintillation and ionospheric Irregularity Drifts observations with SCINDA_GPS and VHF receivers in Kenya. Adv. Space Res. 2013, 51, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwira, C.M.; Lenzing, J.; Olwendo, J.; D’Ujanga, F.M.; Baki, P. A Study of Intense Ionospheric Scintillation Observed During a Quiet Day in the East African Low Latitude Region. Radio Sci. 2013, 48, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahindo, B.M.; Kazadi Mukenga Bantu, A.; Fleury, R.; Zana, A.T.K.; Ndontoni, Z.; Kakule Kaniki, M.; Amory-Mazaudier, C.; Groves, K. Contribution à l’étude de la scintillation ionosphérique équatoriale surla crête sud de l’Afrique. J. Sci. 2017, 17, 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Mahrous, A.; Ibrahim, M.; Makram, I.; Berdermann, J.; Salah, H.M. Ionospheric scintillations detected by SCINDA-Helwan station during St. Patrick’s Day geomagnetic storm. NRIAG J. Astron. Geophys. 2018, 7, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotova, D.; Jin, Y.; Spogli, L.; Wood, A.G.; Urbar, J.; Rawlings, J.T.; Whittaker, I.C.; Alfonsi, L.; Clausen, L.B.; Høeg, P.; et al. Electron density fluctuations from Swarm as a proxy for ground-based scintillation data: A statistical perspective. Adv. Space Res. 2022, in press. [CrossRef]

- Kauristie, K.; Andries, J.; Beck, P.; Berdermann, J.; Berghmans, D.; Cesaroni, C.; De Donder, E.; de Patoul, J.; Dierckxsens, M.; Doornbos, E.; et al. Space Weather Services for Civil Aviation—Challenges and Solutions. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IGS. Available online: https://igs.org/network/ (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- SOPAC. Available online: http://sopac-old.ucsd.edu/sopacDescription.shtml (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- IGN in France. Available online: Ftp://igs.ign.fr//pub/igs/data/ (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- BKG in Germany. Available online: https://igs.bkg.bund.de/ (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- GAGE/UNAVCO. Available online: https://www.unavco.org/what-we-do/gage-facility/ (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- AFREF. Available online: http://afrefdata.org/ (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- TRIGNET. Available online: http://www.trignet.co.za/ (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- AMMA. Available online: https://grgs.obs-mip.fr/recherche/projets/amma/ (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- SAGAIE. Available online: Ftp://regina-public-sef.cnes.fr/Niveau0/SAGAIE/pub (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- SONEL. Available online: https://www.sonel.org/-GPS-.html?lang=en (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- OMNISTAR. Available online: https://www.omnistar.com/about-us/ (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Magnetometers Data Center. Available online: http://magnetometers.bc.edu/index.php/amber2 (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Anad, F.; Amory-Mazaudier, C.; Hamoudi, M.; Bourouis, S.; Abtout, A.; Yizengaw, E. Sq solar variation at Médéa Observatory (Algeria), from 2008 to 2011. Adv. Space Res. 2016, 58, 1682–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honore, M.E.; Anad, F.; Ngabireng, M.C.; Mbane, B.C. Sq (H) Solar Variation at Yaoundé-Came-roon AMBER Station from 2011 to 2014. Int. J. Geosci. 2017, 8, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honore, M.E.; Kosh, D.; Mbané, B.C. Day-to-Day Variability of H Component of Geomagnetic Field in Central African Sector Provided by Yaoundé-Cameroon Amber Station. Int. J. Geosci. 2014, 5, 1190–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: http://magdas2.serc.kyushu-u.ac.jp/station/index.html (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Takla, E.M.; Yumoto, K.; Cardinal, M.G.; Abe, S.; Fujimoto, A.; Ikeda, A.; Tokunaga, T.; Yamazaki, Y.; Uo-zumi, T.; Mahrous, A.; et al. A study of latitudinal dependence of Pc 3-4 amplitudes at 96º magnetic meridian stations in Africa. Sun Geosph. 2011, 6, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Omondi, G.E.; Baki, P.; Ndinya, B.O. Quiet time correlation between the Geomagnetic Field variations and the Dynamics of the East African equatorial ionosphere. Int. J. Astrophys. Space Sci. 2017, 5, 6–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hawary, R.E.; Yumoto, K.K.; Mahrous, A.; Ghamry, E.; Meloni, A.; Badi, K.; Kianji, G.; Uiso, S.C.B.; Mwiinga, N.; Jao, L.L.; et al. Annual and semi-annual Sq variations at 96° MM MAGDAS I and II stations in Africa. Earth Planets Space 2012, 66, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shimeis, A.; Fathy, I.; Amory-Mazaudier, C.; Fleury, R.; Mahrous, A.M.; Yumoto, K.; Groves, K. Signature of the Coronal Hole on near the North Crest Equatorial Anomaly over Egypt during the strong Geomagnetic Storm 5th April 2010. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2012, 117, A07309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honore, M.E.; Amaechi, P.O.; Daika, A.; Aziz, D.K.A.; Kaab, M.; Mbane, C.B.; Benkhaldoun, Z. Longitudinal Variability of the Vertical Drift Velocity Inferred from Ground-Based Magnetometers and C/NOFS Observations in Africa. Int. J. Geosci. 2022, 3, 657–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omondi, S.; Akimasa, Y.; Waheed, K.Z.; Fathy, I.; Ayman, M. Alex magnetometer and telluric station in Egypt: First results on pulsation analysis. Adv. Space Res. 2022, 72, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intermagnet. Available online: https://www.intermagnet.org/imos/imotblobs-eng.php (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Zaourar, N.; Amory-Mazaudier, C.; Fleury, R. Hemispheric asymmetries in the ionosphere response observed during the high-speed solar wind streams of the 24–28 August 2010. Adv. Space Res. 2017, 59, 2229–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotzé, P.B.; Cilliers, P.J.; Sutcliffe, P.R. The role of SANSA’s geomagnetic observation network in space weather monitoring: A review. Space Weather 2015, 13, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahayo, E.; Kotzé, P.B.; Cilliers, P.J.; Lotz, S. Observations from SANSA’s geomagnetic network during the Saint Patrick’s Day storm of 17–18 March 2015. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2019, 115, 5204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CALLISTO Data. Available online: http://e-callisto.org/ (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Minta, F.N.; Nozawa, S.I.; Kozarev, K.; Elsaid, A.; Mahrous, A.A. Solar radio bursts observations by Egypt-Alexandria CALLISTO spectrometer: First results. Adv. Space Res. 2022, 72, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SANDMIS Data. Available online: https://sandims.sansa.org.za/ (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- INGV Data. Available online: http://www.eswua.ingv.it/ (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- AGU Basu Awards. Available online: https://honors.agu.org/sfg/basu-early-career-award-in-sun-earth-systems-science/ (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- AGU Africa Awards. Available online: https://www.agu.org/Honor-and-Recognize/Honors/Union-Awards/Africa-Award-Space-Science (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Available online: www.girgea.org (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Amory-Mazaudier, C.; Fleury, R.; Petitdidier, M.; Soula, S.; Masson, F.; Menvielle, M.; Damé, L.; Berthelier, J.-J.; Georgis, L.; Philippon, N.; et al. Recent Advances in Atmospheric, Solar-Terrestrial Physics and Space Weather, from a North-South network of scientists Results and Capacity Building. Sun Geosph. 2017, 12, 21–69. [Google Scholar]

- Loutfi, A.; Pitout, A.F.; Bounhir, Z.; Benkhaldoun, Z.; Makela, J.J. Interhemispheric asymmetry of the equatorial ionization anomaly (EIA) on the African sector over 3 years (2014–2016): Effects of thermospheric meridional winds. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2021, 127, 29902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://cosparhq.cnes.fr/awards/vikram-sarabhai-medal/ (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Amory-Mazaudier, C.; Radicella, S.; Doherty, P.; Gadimova, S.; Fleury, R.; Nava, B.; Anas, E.; Petitdidier, M.; Migoya-Orué, Y.; Alazo, K.; et al. Development of research capacities in space weather: A successful international cooperation. J. Space Weather Space Clim. 2021, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).