Seasonal Levels, Sources, and Health Risks of Heavy Metals in Atmospheric PM2.5 from Four Functional Areas of Nanjing City, Eastern China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. PM2.5 Sampling

2.3. Heavy Metal Analyses

2.4. Calculation of the Enrichment Factors (EFs) for Source Identification

2.5. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

2.6. Human Health Risk Assessments (HHRAs)

2.7. Statistics

3. Results and Discussion

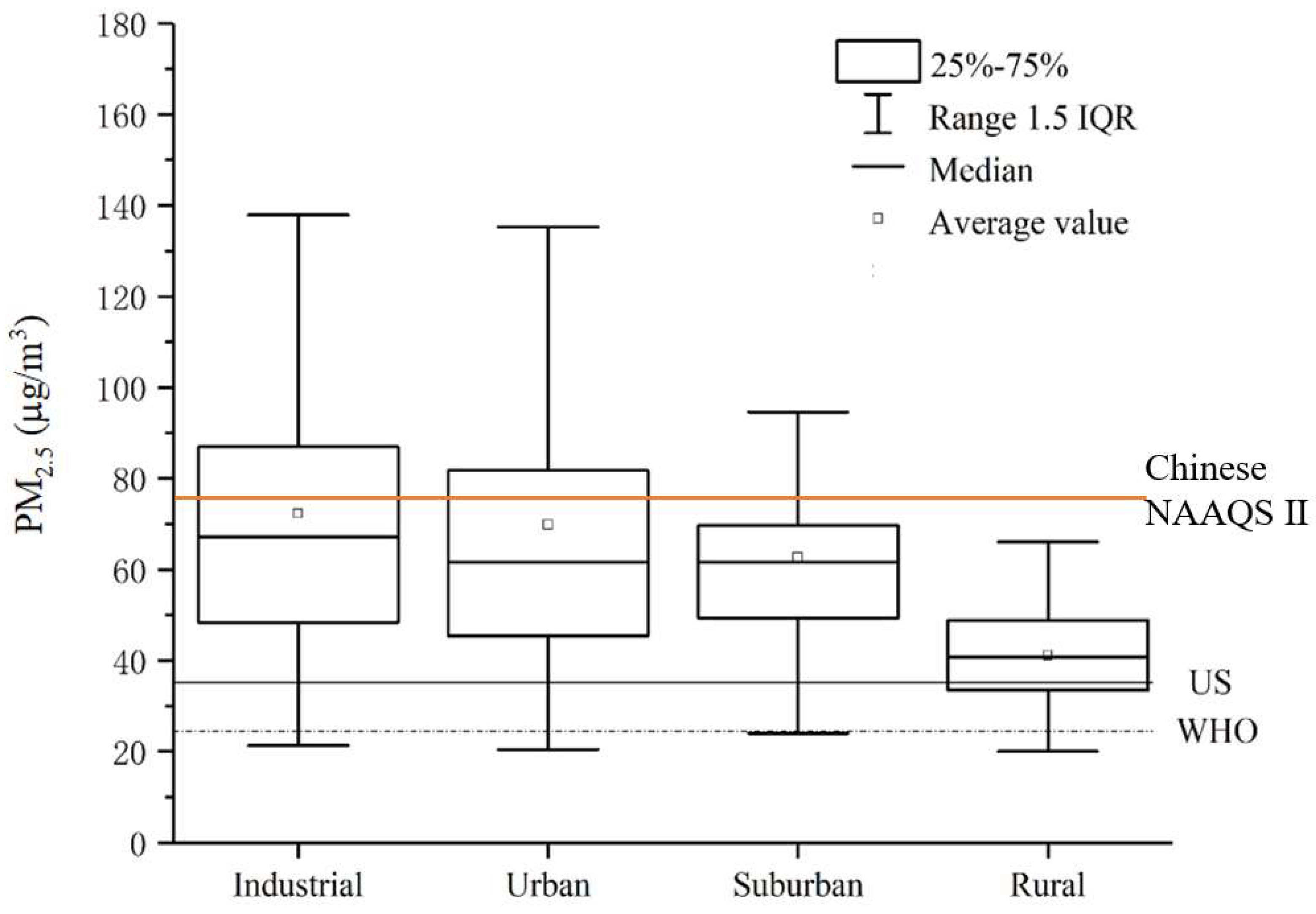

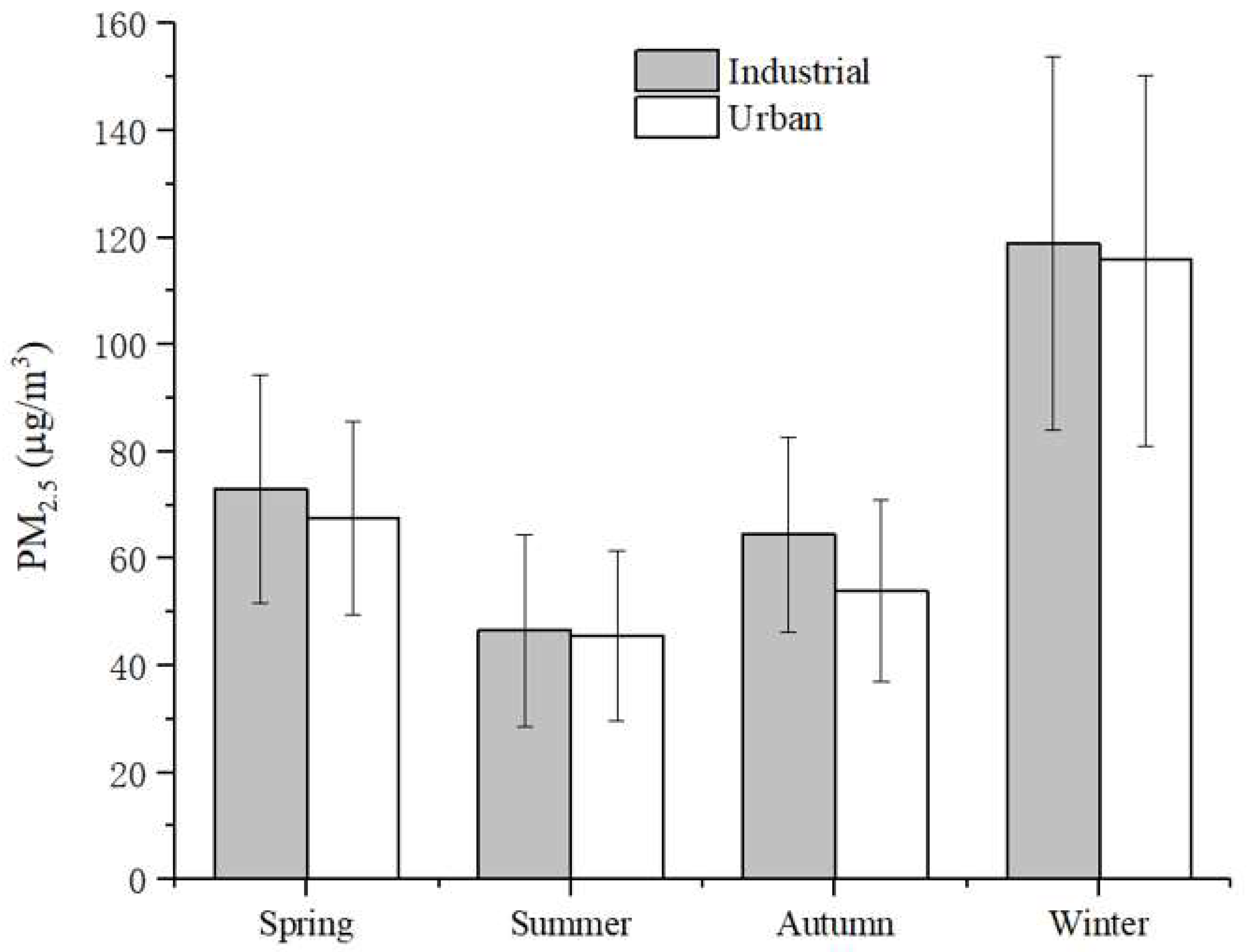

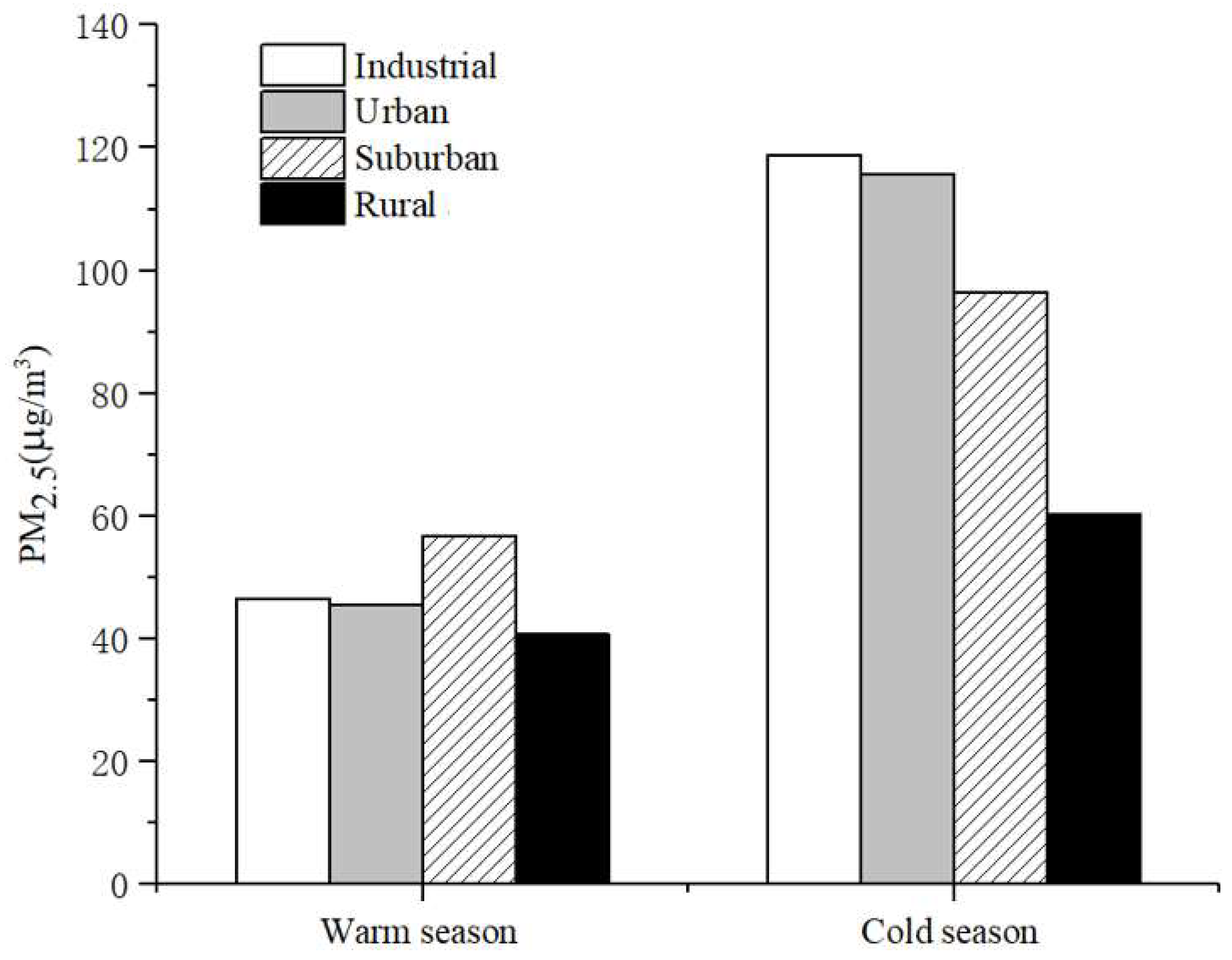

3.1. PM2.5 Concentration Levels in Different Urban Functional Areas

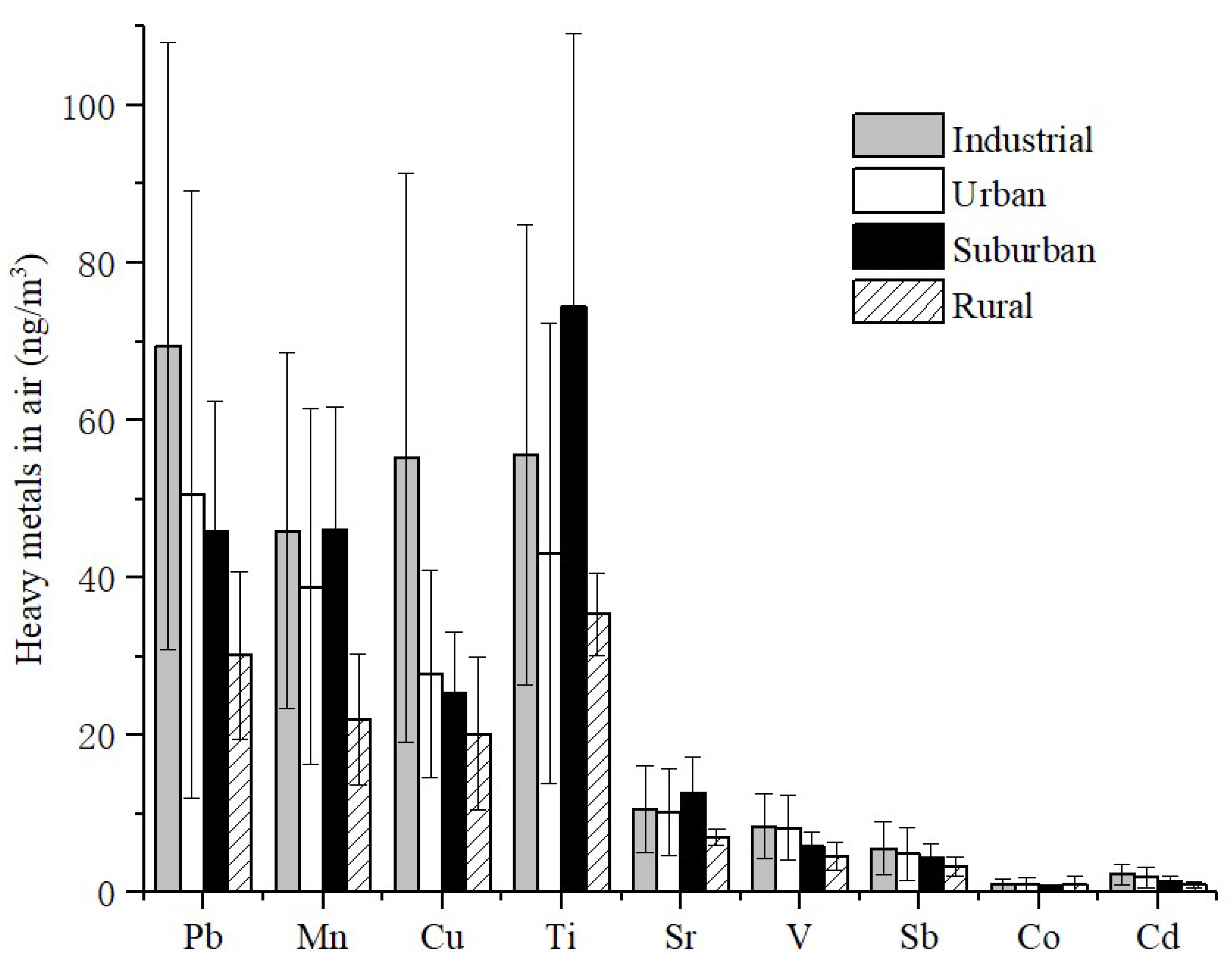

3.2. Seasonal Distribution of PM2.5-Bound Heavy Metal Concentrations in Different Urban Functional Areas

3.3. Source Identification of Airborne Metals in Different Urban Functional Areas

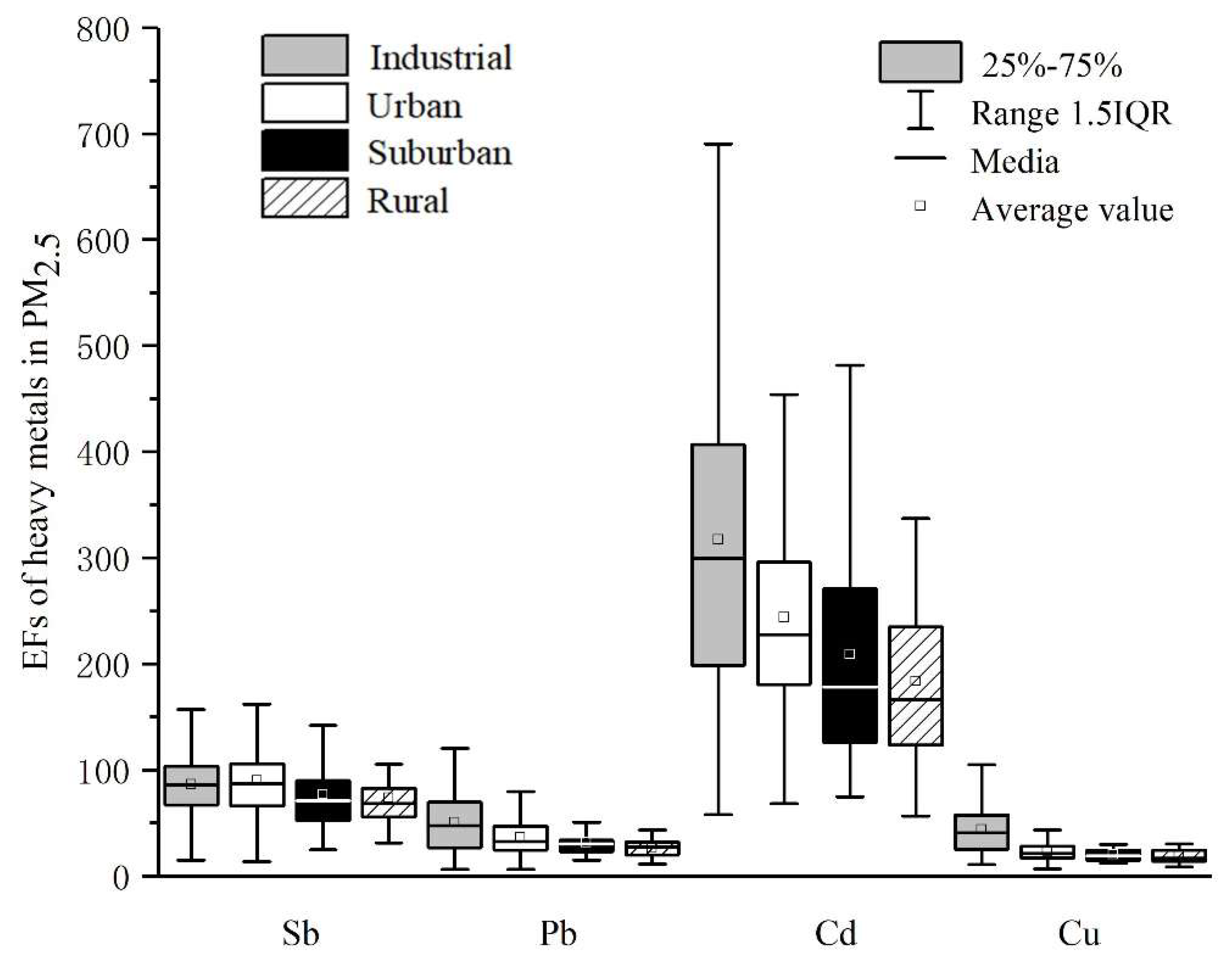

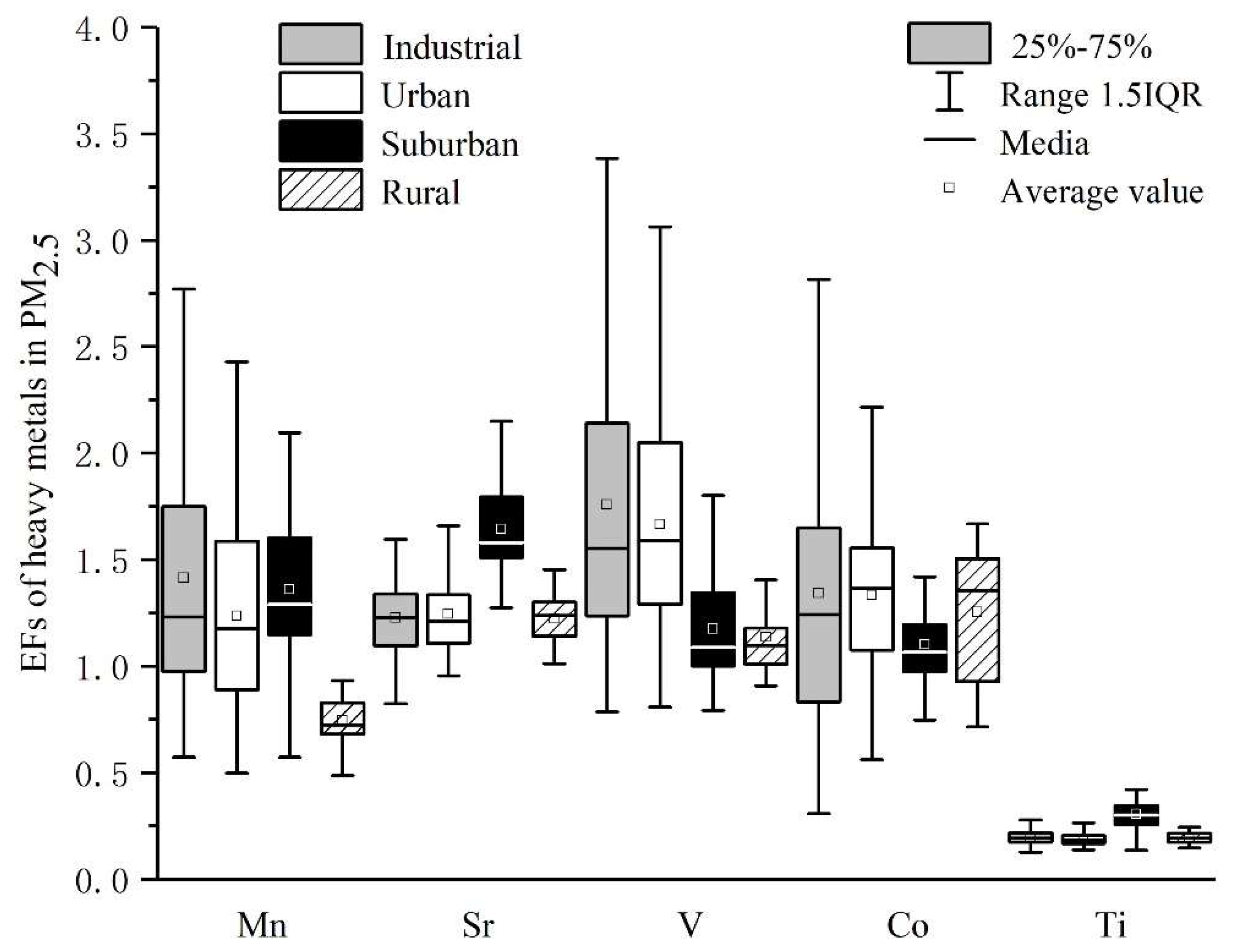

3.3.1. Sources Implied by EFs

3.3.2. Sources Implied by PCA

3.4. Spatial Characteristics of Human Health Risks of Airborne Metals

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, J.J.; Shen, Z.X.; Chow, J.C.; Watson, J.G.; Han, Y.M. Winter and summer PM2.5 chemical compositions in fourteen Chinese cities. J. Air. Waste. Manage. 2012, 62, 1214–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.J.; Kim, B.; Lee, K. Air pollution exposure and cardiovascular disease. Toxicol. Res. 2014, 30, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Luo, X.S.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, Q.; Wu, D.; Sun, X.; Wu, L.; Jin, L. Summer-winter differences of PM2.5 toxicity to human alveolar epithelial cells (A549) and the roles of transition metals. Ecotox. Environ. Saf. 2018, 165, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, W.F.; Ma, Z.Y.; Ha, X.Z. Spatial-temporal patterns of PM2.5 concentrations for 338 Chinese cities. Sci. Total Environ 2018, 631–632, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; He, J.; Lu, X.; She, J.; Guan, Z. Spatial and Temporal Variations of PM2.5 and Its Relation to Meteorological Factors in the Urban Area of Nanjing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2016, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.S.; Yu, S.; Li, X.D. Distribution, availability, and sources of trace metals in different particle size fractions of urban soils in Hong Kong: Implications for assessing the risk to human health. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.G.; Li, J.; Qu, Y.; Han, T.; Hou, L.; Gu, J.; Chen, C.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, T.; et al. Formation and evolution mechanism of regional haze: a case study in the megacity Beijing, china. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 4501–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pey, J.; Querol, X.; Alastuey, A. Discriminating the regional and urban contributions in the North-Western Mediterranean: PM levels and composition. Atmos. Environ. 2010, 44, 1587–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, T.S.; Ana, M.O.; Cruz, J.M.; Tormen, L.; Bascunan, V.L.A.; Azevedo, P.A.; Garcia, C.A.B.; Alves, J.; Araujo, R.G.O. Characterisation and source identification of the total airborne particulate matter collected in an urban area of Aracaju, Northeast, Brazil. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 226, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanraj, R.; Azeez, P.A.; Priscilla, T. Heavy metal in airborne particulate matter of urban Coimbatore. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2004, 47, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, M. Concentrations of cadmium, lead, mercury and arsenic in Chinese market milled rice and associated population health risk. Food Control 2010, 21, 1757–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Cheng, S.; Wang, X.; Nie, W.; Xu, P.; Gao, X.; Yuan, C.; Wang, W. Source identification and health impact of PM2.5 in a heavily polluted urban atmosphere in China. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 75, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalvatzaki, E.; Chatoutsidou, S.; Lehtomäki, H.; Almeida, S.; Eleftheriadis, K.; Hänninen, O.; Lazaridis, M. Characterization of Human Health Risks from Particulate Air Pollution in Selected European Cities. Atmosphere 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimissis, A.; Philippopoulos, K.; Tzanis, C.G.; Deligiorgi, D. Spatial estimation of urban air pollution with the use of artificial neural network models. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 191, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, M.; Galatioto, F.; Bell, M.; Namdeo, A.; Bergantino, A.S. Improving the prediction of air pollution peak episodes generated by urban transport networks. Environ. Sci. Policy. 2016, 60, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanis, C.G.; Alimissis, A.; Philippopoulos, K.; Deligiorgi, D. Applying linear and nonlinear models for the estimation of particulate matter variability. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 246, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Liu, J.; Han, Z.; Yang, W. Lead in Chinese villager house dust: Geographical variation and influencing factors. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 207, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Luo, X.S.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Hong, Y.; Pang, Y.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y.; Jin, L. Seasonally varied cytotoxicity of organic components in PM2.5 from urban and industrial areas of a Chinese megacity. Chemosphere 2019, 230, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.S.; Ip, C.C.M.; Li, W.; Tao, S.; Li, X.D. Spatial-temporal variations, sources, and transport of airborne inhalable metals (PM10) in urban and rural areas of northern china. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2014, 14, 13133–13165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.S.; Zhao, Z.; Xie, J.W.; Luo, J.; Chen, Y.B.; Li, H.; Jin, L. Pulmonary bioaccessibility of trace metals in PM2.5 from different megacities simulated by lung fluid extraction and DGT method. Chemosphere 2019, 218, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, L.; Jin, L.; Li, J.; Fu, P.; Yang, W.; Liu, D.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Z.; Li, X. PM2.5 in the Yangtze River Delta, China: Chemical compositions, seasonal variations, and regional pollution events. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 223, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birke, M.; Rauch, U.; Hofmann, F. Tree bark as a bioindicator of air pollution in the city of Stassfurt, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. J. Geochem. Explor. 2018, 187, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wang, L.; Li, L.Y.; Lei, K.; Huang, L.; Kang, D. Multivariate statistical analysis of heavy metals in street dust of Baoji, NW China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 173, 744–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doabi, S.A.; Afyuni, M.; Karami, M. Multivariate statistical analysis of heavy metals contamination in atmospheric dust of Kermanshah province, western Iran, during the spring and summer 2013. J. Geochem. Explor. 2017, 180, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Yu, H.; Su, X.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Pan, Y.; Sun, J.H. Chemical composition and source apportionment of PM2.5 during Chinese Spring Festival at Xinxiang, a heavily polluted city in North China: Fireworks and health risks. Atmos. Res. 2016, 182, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Rabha, R.; Chowdhury, M.; Padhy, P.K. Source and chemical species characterization of PM10 and human health risk assessment of semi-urban, urban and industrial areas of West Bengal, India. Chemosphere 2018, 207, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betha, R.; Behera, S.N.; Balasubramanian, R. 2013 Southeast Asian smoke haze: fractionation of particulate-bound elements and associated health risk. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 4327–4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Jiang, M.; Jing, H.; Sheng, W.; Wang, X.; Han, J.; Wang, L. Analysis of serum levels of 15 trace elements in breast cancer patients in Shandong, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2015, 22, 7930–7935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA. Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund, Volume I. In Human Health Evaluation Manual (Part A); EPA/540/1-89/002; US Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Emergency and Remedial Response: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- US EPA. Exposure Factors Handbook 2011 Edition; EPA/600/R-09/052F; US Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Emergency and Remedial Response: Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- US EPA. Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund Volume I. In Human Health Evaluation Manual (Part F, Supplemental Guidance for Inhalation Risk Assessment); EPA/540/R/070/002; US Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Emergency and Remedial Response: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- CMEP. Ambient Air Quality Standards (In Chinese); GB 3095–2012; Chinese Ministry of Environmental Protection (CMEP), China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, L.; Xu, C.; Li, N.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Xu, D. Source Apportionment and Influencing Factor Analysis of Residential Indoor PM2.5 in Beijing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudarzi, G.; Shirmardi, M.; Naimabadi, A.; Ghadiri, A.; Sajedifar, J. Chemical and organic characteristics of PM2.5 particles and their in-vitro cytotoxic effects on lung cells: The Middle East dust storms in Ahvaz, Iran. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, M.; Latif, M.T.; Mohamed, A.F. The PM10 compositions, sources and health risks assessment in mechanically ventilated office buildings in an urban environment. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2015, 9, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.L.; Yang, F.G.; Zhao, W.J.; Zhao, Y.G.; Yang, J.L.; Gong, Z.T. Historical change of soil Pb content and Pb isotope signatures of the cultural layers in urban Nanjing. Catena 2007, 69, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, L.; Sui, X.; Yao, L.; Zheng, L.; Wen, L.; Xu, C.; Wang, W. Indoor PM2.5 and its chemical composition during a heavy haze–fog episode at Jinan, China. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 99, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, R.V.; Dominguez, E.R. Health risk by inhalation of PM2.5 in the metropolitan zone of the City of Mexico. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2009, 72, 866–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Yang, Y.; Xu, Z. PM10 and PM2.5 and Health Risk Assessment for Heavy Metals in a Typical Factory for Cathode Ray Tube Television Recycling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 12469–12476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Ye, H.; Xu, C.; Yao, Y.; Liu, W. Highly time- and size-resolved fingerprint analysis and risk assessment of airborne elements in a megacity in the Yangtze River Delta, china. Chemosphere 2015, 119, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satsangi, P.G.; Yadav, S.; Pipal, A.S.; Kumbhar, N. Characteristics of trace metals in fine (PM2.5) and inhalable (PM10) particles and its health risk assessment along with in-silico approach in indoor environment of India. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 92, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metals | SF 1 | RfD 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Cd | 6.3 | 1 × 10−3 |

| Co | 9.8 | 5.7 × 10−6 |

| Pb | -- | 3.5 × 10−3 |

| Mn | -- | 1.4 × 10−5 |

| Cu | -- | 4 × 10−2 |

| Regions | Year | Sb | Pb | Co | Cd | Mn | V | Cu | Ti | Sr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO AQG | 5 | 150 | ||||||||

| Industrial area a (n = 102) | 2016 | 5.63 | 69.5 | 1.02 | 2.34 | 45.9 | 8.43 | 55.3 | 55.6 | 10.6 |

| Urban area a (n = 102) | 2016 | 4.96 | 50.6 | 1.06 | 1.95 | 38.9 | 8.24 | 27.8 | 43.1 | 10.2 |

| Suburban area a (n = 27) | 2016 | 4.43 | 45.9 | 0.82 | 1.47 | 46.0 | 5.85 | 25.4 | 74.4 | 12.7 |

| Rural area a (n = 20) | 2016 | 3.34 | 30.1 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 22.0 | 4.65 | 20.2 | 35.4 | 7.12 |

| Beijing (China) b | 2013–2014 | 145 | 1.93 | 54.4 | 2.40 | 35.4 | 1.19 | |||

| Athens (Greece) c | 2010 | 6.01 | 3.53 | 15.0 | ||||||

| Ahvaz (Iran) d | 2016 | 4.4 | 0.004 | 6 |

| Location | Season | Pb | Mn | Cu | Ti | Sr | V | Sb | Co | Cd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial area | Spring (n = 34) | 79.9 | 45.9 | 48.8 | 50.2 | 8.14 | 8.29 | 5.98 | 0.80 | 2.12 |

| Summer (n = 28) | 54.3 | 36.3 | 39.1 | 44.0 | 9.54 | 7.72 | 4.81 | 0.82 | 2.19 | |

| Autumn (n = 22) | 79.5 | 53.2 | 41.5 | 47.6 | 11.3 | 10.0 | 5.31 | 1.56 | 2.97 | |

| Winter (n = 28) | 63.0 | 52.5 | 86.9 | 93.9 | 16.2 | 7.95 | 5.04 | 1.08 | 2.24 | |

| Urban area | Spring (n = 34) | 47.9 | 36.0 | 26.3 | 40.7 | 8.00 | 8.67 | 4.93 | 1.14 | 1.61 |

| Summer (n = 28) | 39.7 | 27.3 | 21.4 | 33.2 | 6.95 | 7.17 | 4.57 | 0.92 | 1.67 | |

| Autumn (n = 22) | 42.6 | 38.0 | 25.6 | 40.8 | 9.60 | 7.62 | 4.74 | 1.11 | 2.04 | |

| Winter (n = 28) | 70.8 | 48.9 | 70.3 | 82.4 | 12.6 | 8.48 | 5.13 | 1.21 | 2.32 |

| Elements | Industrial Area | Urban Area | Suburban Area | Rural Area | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | |

| Sb | 0.353 | 0.009 | 0.678 | 0.191 | 0.363 | 0.758 | 0.129 | 0.165 | 0.383 | 0.656 | 0.050 | 0.728 | 0.215 | 0.071 |

| Pb | 0.064 | 0.254 | 0.796 | 0.042 | 0.054 | 0.884 | 0.187 | 0.112 | 0.085 | 0.843 | 0.097 | 0.720 | 0.023 | 0.482 |

| Co | 0.210 | 0.868 | 0.033 | 0.204 | 0.724 | 0.123 | 0.229 | 0.790 | 0.221 | 0.202 | 0.031 | 0.045 | 0.896 | 0.133 |

| Cd | 0.268 | 0.069 | 0.826 | 0.554 | 0.221 | 0.499 | 0.159 | 0.041 | 0.051 | 0.879 | 0.109 | 0.030 | 0.154 | 0.940 |

| Mn | 0.162 | 0.856 | 0.349 | 0.165 | 0.322 | 0.149 | 0.769 | 0.276 | 0.756 | 0.201 | 0.412 | 0.835 | 0.049 | 0.029 |

| V | 0.433 | 0.670 | 0.264 | 0.268 | 0.758 | 0.072 | 0.079 | 0.799 | 0.043 | 0.261 | 0.311 | 0.484 | 0.696 | 0.053 |

| Cu | 0.100 | 0.347 | 0.701 | 0.106 | 0.611 | 0.534 | 0.161 | 0.841 | 0.150 | 0.323 | 0.718 | 0.028 | 0.265 | 0.298 |

| Ti | 0.844* | 0.102 | 0.107 | 0.790 | 0.303 | 0.048 | 0.303 | 0.155 | 0.891 | 0.159 | 0.906 | 0.161 | 0.150 | 0.276 |

| Al | 0.794 | 0.404 | 0.339 | 0.861 | 0.405 | 0.094 | 0.185 | 0.893 | 0.290 | 0.118 | 0.958 | 0.168 | 0.155 | 0.046 |

| Sr | 0.848 | 0.315 | 0.205 | 0.840 | 0.118 | 0.002 | 0.331 | 0.849 | 0.376 | 0.016 | 0.948 | 0.218 | 0.083 | 0.155 |

| Eigenvalue > 1 | 3.27 | 2.86 | 2.82 | 3.228 | 2.32 | 1.99 | 1.77 | 4.51 | 2.69 | 2.24 | 4.92 | 2.37 | 1.53 | 1.44 |

| Variance % | 27.2 | 23.9 | 23.5 | 26.9 | 19.3 | 16.7 | 14.7 | 37.6 | 22.4 | 18.7 | 40.9 | 19.7 | 12.8 | 11.9 |

| Cumulative % | 27.2 | 51.1 | 74.6 | 26.9 | 46.2 | 62.9 | 77.6 | 37.6 | 60.0 | 78.7 | 40.9 | 60.7 | 73.4 | 85.4 |

| Source | Natural source | Natural source | Natural source | Natural source | ||||||||||

| Metallurgical chemical dust | Automobile exhaust | Automobile exhaust | ||||||||||||

| Health Risk | Elements | Industrial Area | Urban Area | Suburban Area | Rural Area | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult | Children | Adult | Children | Adult | Children | Adult | Children | ||

| Noncarcinogenic Hazard | Pb | 1.52 × 10−3 | 8.16 × 10−4 | 1.10 × 10−3 | 5.94 × 10−4 | 1.00 × 10−3 | 5.38 × 10−4 | 6.57 × 10−4 | 3.54 × 10−4 |

| Co | 1.37 × 10−2 | 7.35 × 10−3 | 1.42 × 10−2 | 7.64 × 10−3 | 1.10 × 10−2 | 5.91 × 10−3 | 1.37 × 10−2 | 7.35 × 10−3 | |

| Cd | 1.79 × 10−4 | 9.62 × 10−5 | 1.49 × 10−4 | 8.01 × 10−5 | 1.12 × 10−4 | 6.04 × 10−5 | 7.71 × 10−5 | 4.15 × 10−5 | |

| Mn | 2.50 × 10−1 | 1.35 × 10−1 | 2.12 × 10−1 | 1.14 × 10−1 | 2.51 × 10−1 | 1.35 × 10−1 | 1.20 × 10−1 | 6.45 × 10−2 | |

| Cu | 1.05 × 10−4 | 5.68 × 10−5 | 5.30 × 10−5 | 2.85 × 10−5 | 4.84 × 10−5 | 2.61 × 10−5 | 3.85 × 10−5 | 2.07 × 10−5 | |

| CarcinogenicRisk | Co | 1.17 × 10−6 | 1.22 × 10−6 | 9.44 × 10−7 | 1.17 × 10−6 | ||||

| Cd | 1.73 × 10−6 | 1.44 × 10−6 | 1.09 × 10−6 | 7.47 × 10−7 | |||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, L.; Luo, X.-S.; Li, H.; Cang, L.; Yang, J.; Yang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Tang, M. Seasonal Levels, Sources, and Health Risks of Heavy Metals in Atmospheric PM2.5 from Four Functional Areas of Nanjing City, Eastern China. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10070419

Wu L, Luo X-S, Li H, Cang L, Yang J, Yang J, Zhao Z, Tang M. Seasonal Levels, Sources, and Health Risks of Heavy Metals in Atmospheric PM2.5 from Four Functional Areas of Nanjing City, Eastern China. Atmosphere. 2019; 10(7):419. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10070419

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Lichun, Xiao-San Luo, Hongbo Li, Long Cang, Jie Yang, Jiangli Yang, Zhen Zhao, and Mingwei Tang. 2019. "Seasonal Levels, Sources, and Health Risks of Heavy Metals in Atmospheric PM2.5 from Four Functional Areas of Nanjing City, Eastern China" Atmosphere 10, no. 7: 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10070419

APA StyleWu, L., Luo, X.-S., Li, H., Cang, L., Yang, J., Yang, J., Zhao, Z., & Tang, M. (2019). Seasonal Levels, Sources, and Health Risks of Heavy Metals in Atmospheric PM2.5 from Four Functional Areas of Nanjing City, Eastern China. Atmosphere, 10(7), 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10070419