The Evolving Role of Artificial Intelligence in Medical Genetics: Advancing Healthcare, Research, and Biosafety Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Enhancing Diagnostic Yield in Genetic Disease

1.2. The Rise of Imaging-Genetics: Digital Biopsies

1.3. Predictive and Prophylactic Medicine

1.4. Tailoring Therapeutics with Pharmacogenomics (PGx)

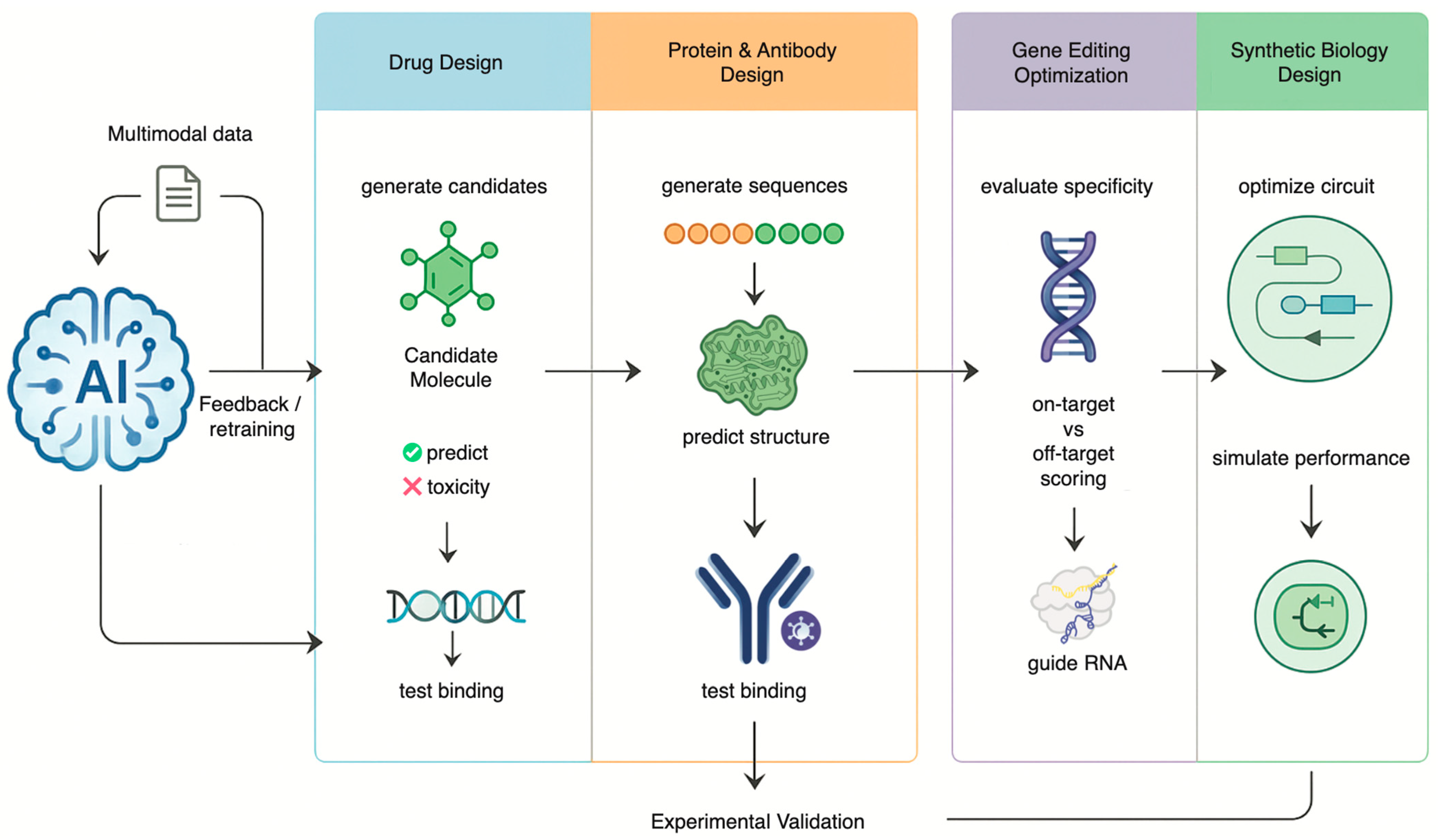

2. Engineering Biology: AI in Therapeutic Design and Genetic Modification

2.1. Accelerating Drug Discovery and Development

2.2. Generative AI in DNA, Protein and Antibody Engineering

2.3. Refining Gene Editing with Precision

3. Navigating the New Frontier: Biosafety, Governance, and Ethical Imperatives

3.1. Data Privacy and Security in the AI Era

3.2. Algorithmic Bias and Health Equity

3.3. The Dual-Use Dilemma: Biosecurity in an Age of AI-Enabled Genetic Engineering

4. Challenges and Future Directions

4.1. The Emergence of the Digital Twin in Precision Medicine

4.2. The Power of Multimodal AI

4.3. A Call for Interdisciplinary Collaboration

4.4. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Topol, E.J. High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eraslan, G.; Avsec, Ž.; Gagneur, J.; Theis, F.J. Deep learning: New computational modelling techniques for genomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, S.; McPherson, J.D.; McCombie, W.R. Coming of age: Ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, E.S.; Linton, L.M.; Birren, B.; Nusbaum, C.; Zody, M.C.; Baldwin, J.; Devon, K.; Dewar, K.; Doyle, M.; FitzHugh, W.; et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 2001, 409, 860–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auton, A.; Brooks, L.D.; Durbin, R.M.; Garrison, E.P.; Kang, H.M.; Korbel, J.O.; Marchini, J.L.; McCarthy, S.; McVean, G.A.; Abecasis, G.R. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, Y.; Seldin, M.; Lusis, A. Multi-omics approaches to disease. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karczewski, K.J.; Snyder, M.P. Integrative omics for health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Troyanskaya, O.G. Predicting effects of noncoding variants with deep learning-based sequence model. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 931–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beam, A.L.; Kohane, I.S. Big Data and Machine Learning in Health Care. JAMA 2018, 319, 1317–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, A.C.; McMahon, P.; Lu, C. Ending the Diagnostic Odyssey-Is Whole-Genome Sequencing the Answer? JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 821–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.C.; Levy, S.; Huang, J.; Stockwell, T.B.; Walenz, B.P.; Li, K.; Axelrod, N.; Busam, D.A.; Strausberg, R.L.; Venter, J.C. Genetic variation in an individual human exome. PLoS Genet. 2008, 4, e1000160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Liu, C.; Wang, L.; Ai-Ouran, R.; Deisseroth, C.; Pasupuleti, S.; Kim, S.Y.; Li, L.; Rosenfeld, J.A.; Meng, L.; et al. AI-MARRVEL—A Knowledge-Driven AI System for Diagnosing Mendelian Disorders. NEJM AI 2024, 1, AIoa2300009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smedley, D.; Jacobsen, J.O.; Jäger, M.; Köhler, S.; Holtgrewe, M.; Schubach, M.; Siragusa, E.; Zemojtel, T.; Buske, O.J.; Washington, N.L.; et al. Next-generation diagnostics and disease-gene discovery with the Exomiser. Nat. Protoc. 2015, 10, 2004–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.H.; Kim, D.W.; Woo, J.; Lee, K. Explicable prioritization of genetic variants by integration of rule-based and machine learning algorithms for diagnosis of rare Mendelian disorders. Hum. Genom. 2024, 18, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.; Attali, R.; Talmy, T.; Regev, Y.; Mizrahi, N.; Smirin-Yosef, P.; Vossaert, L.; Taborda, C.; Santana, M.; Machol, I.; et al. Evaluation of an automated genome interpretation model for rare disease routinely used in a clinical genetic laboratory. Genet. Med. 2023, 25, 100830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, T.; Dong, Q.; Zhao, Y. Chromosome classification via deep learning and its application to patients with structural abnormalities of chromosomes. Med. Eng. Phys. 2023, 121, 104064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, P.; Leijenaar, R.T.H.; Deist, T.M.; Peerlings, J.; de Jong, E.E.C.; van Timmeren, J.; Sanduleanu, S.; Larue, R.; Even, A.J.G.; Jochems, A.; et al. Radiomics: The bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, D.M.; Rong, R.; Zhan, X.; Xiao, G. Pathology Image Analysis Using Segmentation Deep Learning Algorithms. Am. J. Pathol. 2019, 189, 1686–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanella, G.; Hanna, M.G.; Geneslaw, L.; Miraflor, A.; Werneck Krauss Silva, V.; Busam, K.J.; Brogi, E.; Reuter, V.E.; Klimstra, D.S.; Fuchs, T.J. Clinical-grade computational pathology using weakly supervised deep learning on whole slide images. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coudray, N.; Ocampo, P.S.; Sakellaropoulos, T.; Narula, N.; Snuderl, M.; Fenyö, D.; Moreira, A.L.; Razavian, N.; Tsirigos, A. Classification and mutation prediction from non-small cell lung cancer histopathology images using deep learning. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1559–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehues, J.M.; Quirke, P.; West, N.P.; Grabsch, H.I.; van Treeck, M.; Schirris, Y.; Veldhuizen, G.P.; Hutchins, G.G.A.; Richman, S.D.; Foersch, S.; et al. Generalizable biomarker prediction from cancer pathology slides with self-supervised deep learning: A retrospective multi-centric study. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.J.; Lee, A.; Kang, J.; Song, I.H.; Lee, S.H. Prediction of clinically actionable genetic alterations from colorectal cancer histopathology images using deep learning. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 6207–6223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiot, J.; Vaidyanathan, A.; Deprez, L.; Zerka, F.; Danthine, D.; Frix, A.N.; Lambin, P.; Bottari, F.; Tsoutzidis, N.; Miraglio, B.; et al. A review in radiomics: Making personalized medicine a reality via routine imaging. Med. Res. Rev. 2022, 42, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Hu, P. Radiogenomic association of deep MR imaging features with genomic profiles and clinical characteristics in breast cancer. Biomark. Res. 2023, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kather, J.N.; Pearson, A.T.; Halama, N.; Jäger, D.; Krause, J.; Loosen, S.H.; Marx, A.; Boor, P.; Tacke, F.; Neumann, U.P.; et al. Deep learning can predict microsatellite instability directly from histology in gastrointestinal cancer. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1054–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkamani, A.; Wineinger, N.E.; Topol, E.J. The personal and clinical utility of polygenic risk scores. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khera, A.V.; Chaffin, M.; Aragam, K.G.; Haas, M.E.; Roselli, C.; Choi, S.H.; Natarajan, P.; Lander, E.S.; Lubitz, S.A.; Ellinor, P.T.; et al. Genome-wide polygenic scores for common diseases identify individuals with risk equivalent to monogenic mutations. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1219–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.W.; Mak, T.S.; O’Reilly, P.F. Tutorial: A guide to performing polygenic risk score analyses. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 2759–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdsson, A.I.; Louloudis, I.; Banasik, K.; Westergaard, D.; Winther, O.; Lund, O.; Ostrowski, S.R.; Erikstrup, C.; Pedersen, O.B.V.; Nyegaard, M.; et al. Deep integrative models for large-scale human genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klau, J.H.; Maj, C.; Klinkhammer, H.; Krawitz, P.M.; Mayr, A.; Hillmer, A.M.; Schumacher, J.; Heider, D. AI-based multi-PRS models outperform classical single-PRS models. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1217860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunter, N.B.; Gebre, R.K.; Graff-Radford, J.; Heckman, M.G.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; Lowe, V.J.; Knopman, D.S.; Petersen, R.C.; Ross, O.A.; Vemuri, P.; et al. Machine Learning Models of Polygenic Risk for Enhanced Prediction of Alzheimer Disease Endophenotypes. Neurol. Genet. 2024, 10, e200120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dsouza, V.S.; Leyens, L.; Kurian, J.R.; Brand, A.; Brand, H. Artificial intelligence (AI) in pharmacovigilance: A systematic review on predicting adverse drug reactions (ADR) in hospitalized patients. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2025, 21, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottlieb, A.; Daneshjou, R.; DeGorter, M.; Bourgeois, S.; Svensson, P.J.; Wadelius, M.; Deloukas, P.; Montgomery, S.B.; Altman, R.B. Cohort-specific imputation of gene expression improves prediction of warfarin dose for African Americans. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zack, M.; Stupichev, D.N.; Moore, A.J.; Slobodchikov, I.D.; Sokolov, D.G.; Trifonov, I.F.; Gobbs, A. Artificial Intelligence and Multi-Omics in Pharmacogenomics: A New Era of Precision Medicine. Mayo Clin. Proc. Digit. Health 2025, 3, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchietti, L.F.; Wijaya, B.N.; Armanuly, A.; Hangeldiyev, B.; Jung, H.; Lee, S.; Cha, M.; Kim, H.M. Artificial intelligence-driven computational methods for antibody design and optimization. mAbs 2025, 17, 2528902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.D.T.; Zeng, Y.; Wan, F.; Maus, N.; Gardner, J.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C. A generative artificial intelligence approach for antibiotic optimization. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, S.K. Artificial Intelligence in Small-Molecule Drug Discovery: A Critical Review of Methods, Applications, and Real-World Outcomes. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.; Griffin, I.; Tucker, C.; Smith, D.; Oechsle, O.; Phelan, A.; Rawling, M.; Savory, E.; Stebbing, J. Baricitinib as potential treatment for 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease. Lancet 2020, 395, e30–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, E.; Poli, M.; Durrant, M.G.; Kang, B.; Katrekar, D.; Li, D.B.; Bartie, L.J.; Thomas, A.W.; King, S.H.; Brixi, G. Sequence modeling and design from molecular to genome scale with Evo. Science 2024, 386, eado9336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Dumas, M.; Watson, R.; Vincoff, S.; Peng, C.; Zhao, L.; Hong, L.; Pertsemlidis, S.; Shaepers-Cheu, M.; Wang, T.Z.; et al. PepMLM: Target Sequence-Conditioned Generation of Therapeutic Peptide Binders via Span Masked Language Modeling. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2310.03842v3. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Feng, Q.; Qiao, L.; Wu, H.; Shen, T.; Cheng, Y.; Zheng, S.; Sun, S. Benchmarking all-atom biomolecular structure prediction with FoldBench. Nat. Commun. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. Deep learning in CRISPR-Cas systems: A review of recent studies. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1226182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruffolo, J.A.; Nayfach, S.; Gallagher, J.; Bhatnagar, A.; Beazer, J.; Hussain, R.; Russ, J.; Yip, J.; Hill, E.; Pacesa, M.; et al. Design of highly functional genome editors by modelling CRISPR-Cas sequences. Nature 2025, 645, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jin, R.; Chao, L.; Xu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Yin, D.; Guo, Y.; Fu, Y.; Yang, Y. RNAGenesis: A Generalist Foundation Model for Functional RNA Therapeutics. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koblan, L.W.; Doman, J.L.; Wilson, C.; Levy, J.M.; Tay, T.; Newby, G.A.; Maianti, J.P.; Raguram, A.; Liu, D.R. Improving cytidine and adenine base editors by expression optimization and ancestral reconstruction. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 843–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannu, J.; Bloomfield, D.; MacKnight, R.; Hanke, M.S.; Zhu, A.; Gomes, G.; Cicero, A.; Inglesby, T.V. Dual-use capabilities of concern of biological AI models. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2025, 21, e1012975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, D.; Pannu, J.; Zhu, A.W.; Ng, M.Y.; Lewis, A.; Bendavid, E.; Asch, S.M.; Hernandez-Boussard, T.; Cicero, A.; Inglesby, T. AI and biosecurity: The need for governance. Science 2024, 385, 831–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomi, L.; Huang, Y.; Ohno-Machado, L. Privacy challenges and research opportunities for genomic data sharing. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauneck, A.; Schmalhorst, L.; Kazemi Majdabadi, M.M.; Bakhtiari, M.; Völker, U.; Baumbach, J.; Baumbach, L.; Buchholtz, G. Federated Machine Learning, Privacy-Enhancing Technologies, and Data Protection Laws in Medical Research: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e41588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boscarino, N.; Cartwright, R.A.; Fox, K.; Tsosie, K.S. Federated learning and Indigenous genomic data sovereignty. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2022, 4, 909–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norori, N.; Hu, Q.; Aellen, F.M.; Faraci, F.D.; Tzovara, A. Addressing bias in big data and AI for health care: A call for open science. Patterns 2021, 2, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, T.; Li, H.; Chang, P.-C.; Lin, M.F.; Carroll, A.; McLean, C.Y. Accurate, scalable cohort variant calls using DeepVariant and GLnexus. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 5582–5589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Bedi, A.S.; Velasquez, A.; Guerra, S.; Lin-Gibson, S.; Cong, L.; Qu, Y.; Chakraborty, S.; Blewett, M. A call for built-in biosecurity safeguards for generative AI tools. Nat. Biotechnol. 2025, 43, 845–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Jin, R.; Cong, L.; Wang, M. GeneBreaker: Jailbreak Attacks against DNA Language Models with Pathogenicity Guidance. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.23839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chakraborty, S.; Bedi, A.S.; Mathew, E.; Saravanan, V.; Cong, L.; Velasquez, A.; Lin-Gibson, S.; Blewett, M.; Hendrycs, D. Generative AI for Biosciences: Emerging Threats and Roadmap to Biosecurity. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.15975. [Google Scholar]

- Gisselbaek, M.; Berger-Estilita, J.; Devos, A.; Ingrassia, P.L.; Dieckmann, P.; Saxena, S. Bridging the gap between scientists and clinicians: Addressing collaboration challenges in clinical AI integration. BMC Anesthesiol. 2025, 25, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.; Silva, J.; Azevedo, L.F.; de Lemos, M.S.; Paneque, M. A collaborative model for Medical Genetics services delivery in Portugal: A multidisciplinary perspective. J. Community Genet. 2024, 15, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Li, J.; Fantus, S. Medical artificial intelligence ethics: A systematic review of empirical studies. Digit. Health 2023, 9, 20552076231186064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristou, K.; Katsakiori, P.F.; Papadimitroulas, P.; Strigari, L.; Kagadis, G.C. Digital Twins’ Advancements and Applications in Healthcare, Towards Precision Medicine. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, K.P.; Raza, M.M.; Kvedar, J.C. Health digital twins as tools for precision medicine: Considerations for computation, implementation, and regulation. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipkova, J.; Chen, R.J.; Chen, B.; Lu, M.Y.; Barbieri, M.; Shao, D.; Vaidya, A.J.; Chen, C.; Zhuang, L.; Williamson, D.F.K.; et al. Artificial intelligence for multimodal data integration in oncology. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Prakosa, A.; James, C.; Zimmerman, S.L.; Carrick, R.; Sung, E.; Gasperetti, A.; Tichnell, C.; Murray, B.; et al. Predicting Ventricular Tachycardia Circuits in Patients with Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy using Genotype-specific Heart Digital Twins. medRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, B.D.; Ozyoruk, K.B.; Gelikman, D.G.; Harmon, S.A.; Türkbey, B. The future of multimodal artificial intelligence models for integrating imaging and clinical metadata: A narrative review. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2025, 31, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, H. How genomics and multi-modal AI are reshaping precision medicine. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1660889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekadir, K.; Frangi, A.F.; Porras, A.R.; Glocker, B.; Cintas, C.; Langlotz, C.P.; Weicken, E.; Asselbergs, F.W.; Prior, F.; Collins, G.S.; et al. FUTURE-AI: International consensus guideline for trustworthy and deployable artificial intelligence in healthcare. BMJ 2025, 388, e081554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Application Area | Key AI Technologies | Pros/Benefits | Cons/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostics | Deep Learning, NLP (e.g., AI-MARRVEL) | Integrates multi-modal data; high accuracy in ranking variants. | Requires large training datasets; interpretability issues; validation needed in diverse populations. |

| Imaging-Genetics | CNNs (Radiomics, Comp. Pathology) | Non-invasive digital biopsies; lower cost than sequencing; spatial heterogeneity analysis. | Sensitivity/specificity varies; standardization of imaging protocols required; indirect inference of genotype. |

| Predictive Medicine | Machine Learning (ML-PRS) | Captures non-linear genetic interactions; improved risk stratification for complex diseases. | Major bias toward European ancestry in training data; risk of over-medicalization. |

| Therapeutics | Generative AI, LLMs | Accelerates drug discovery; de novo protein design; optimizes gene editing specificity. | High computational cost; hallucination of non-functional molecules; dual-use biosecurity risks. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.-C.; Tuo, N.; Shi, G.; Li, K.; Song, Z.; Li, Y. The Evolving Role of Artificial Intelligence in Medical Genetics: Advancing Healthcare, Research, and Biosafety Management. Genes 2026, 17, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010006

Wu Y-C, Tuo N, Shi G, Li K, Song Z, Li Y. The Evolving Role of Artificial Intelligence in Medical Genetics: Advancing Healthcare, Research, and Biosafety Management. Genes. 2026; 17(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Ying-Cheng, Nan Tuo, Guoming Shi, Ka Li, Zhenju Song, and Yanying Li. 2026. "The Evolving Role of Artificial Intelligence in Medical Genetics: Advancing Healthcare, Research, and Biosafety Management" Genes 17, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010006

APA StyleWu, Y.-C., Tuo, N., Shi, G., Li, K., Song, Z., & Li, Y. (2026). The Evolving Role of Artificial Intelligence in Medical Genetics: Advancing Healthcare, Research, and Biosafety Management. Genes, 17(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010006