Plant Extracellular Vesicles with Complex Molecular Cargo: A Cross-Kingdom Conduit for MicroRNA-Directed RNA Silencing

Abstract

1. The Discovery of Plant Extracellular Vesicles

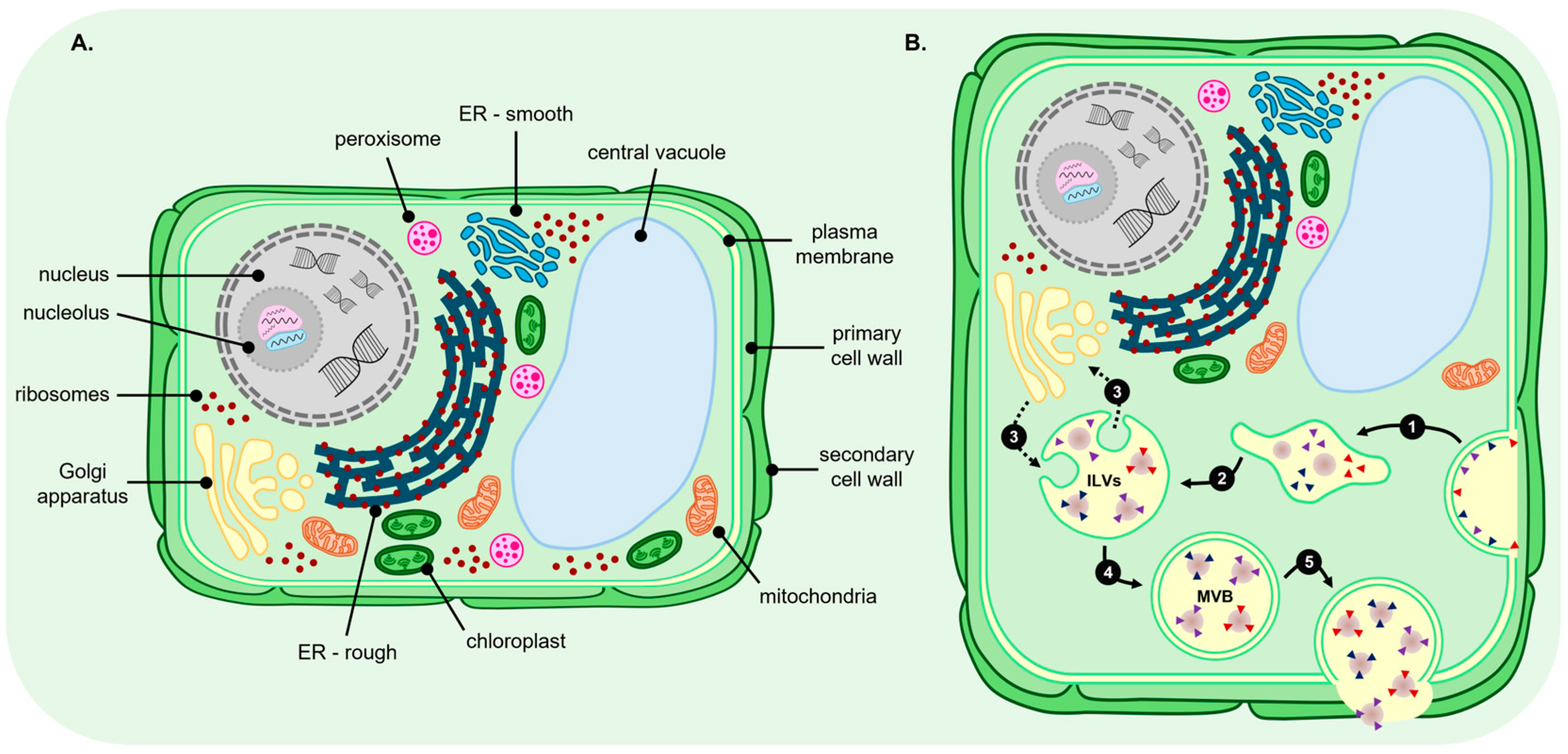

2. Physical Properties of Plant Extracellular Vesicles

3. Biogenesis Pathways for Plant Extracellular Vesicle Production

4. Plant Extracellular Vesicles Harbour Diverse Bioactive Molecular Cargo

4.1. The MicroRNA Cargo of Plant Extracellular Vesicles and Their Roles in Development and Environmental Stress Adaptation

4.2. The MicroRNA Cargo of Plant Extracellular Vesicles and Their Role in Pathogen Defence

4.3. Do Pathogen-Generated Extracellular Vesicles Deliver MicroRNA Effectors to Host Plants?

4.4. Algae Extracellular Vesicles: Do They Mediate a Similar Transportation Role in MicroRNA-Directed Gene Expression Regulation?

5. Future Directions: The Use of Extracellular Vesicles and Their miRNA Cargo in the Agricultural and Aquacultural Settings

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alzahrani, F.A.; Khan, M.I.; Kameli, N.; Alsahafi, E.; Riza, Y.M. Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles and Their Exciting Potential as the Future of Next-Generation Drug Delivery. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosone, A.; Barbulova, A.; Cappetta, E.; Cillo, F.; De Palma, M.; Ruocco, M.; Pocsfalvi, G. Plant Extracellular Vesicles: Current Landscape and Future Directions. Plants 2023, 12, 4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Halilovic, L.; Shi, T.; Chen, A.; He, B.; Wu, H.; Jin, H. Extracellular vesicles: Cross-organismal RNA trafficking in plants, microbes, and mammalian cells. Extracell. Vesicles Circ. Nucleic Acids 2023, 4, 262–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzoni, E.; Bertoldi, A.; Cesaretti, A.; Alabed, H.B.R.; Cerrotti, G.; Pellegrino, R.M.; Buratta, S.; Urbanelli, L.; Emiliani, C. Aloe Extracellular Vesicles as Carriers of Photoinducible Metabolites Exhibiting Cellular Phototoxicity. Cells 2024, 13, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sall, I.M.; Flaviu, T.A. Plant and mammalian-derived extracellular vesicles: A new therapeutic approach for the future. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1215650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaya, T.; Banerjee, A.; Rutter, B.D.; Adekanye, D.; Ross, J.; Hu, G.; Innes, R.W.; Caplan, J.L. The extracellular vesicle proteomes of Sorghum bicolor and Arabidopsis thaliana are partially conserved. Plant Physiol. 2024, 194, 1481–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couch, Y.; Buzàs, E.I.; Di Vizio, D.; Gho, Y.S.; Harrison, P.; Hill, A.F.; Lötvall, J.; Raposo, G.; Stahl, P.D.; Théry, C.; et al. A brief history of nearly EV-erything—The rise and rise of extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocholatá, M.; Malý, J.; Kříženecká, S.; Janoušková, O. Diversity of extracellular vesicles derived from calli, cell culture and apoplastic fluid of tobacco. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zeng, A.; Li, L.; Zhao, W. Emerging Roles of Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Biotherapeutics: Advances, Applications, and Future Perspectives. Adv. Biol. 2025, 9, e2500008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.L.; Ehlers, K.; Kogel, K.H.; van Bel, A.J.E.; Hückelhoven, R. Multivesicular compartments proliferate in susceptible and resistant MLA12-barley leaves in response to infection by the biotrophic powdery mildew fungus. New Phytol. 2006, 172, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micali, C.O.; Neumann, U.; Grunewald, D.; Panstruga, R.; O’Connell, R. Biogenesis of a specialized plant-fungal interface during host cell internalization of Golovinomyces orontii haustoria. Cell. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Qiao, L.; Wang, M.; He, B.; Lin, F.M.; Palmquist, J.; Huang, S.D.; Jin, H. Plants send small RNAs in extracellular vesicles to fungal pathogen to silence virulence genes. Science 2018, 360, 1126–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regente, M.; Pinedo, M.; Clemente, H.S.; Balliau, T.; Jamet, E.; De La Canal, L. Plant Extracellular Vesicles Are Incorporated by a Fungal Pathogen and Inhibit Its Growth. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 5485–5495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, W.H.; Ji, S.X.; Zhang, F.B.; Song, H.D.; Wang, J.X.; Fan, X.P.; Xie, R.; Liu, S.S.; Wang, X.W. A small RNA effector conserved in herbivore insects suppresses host plant defense by cross-kingdom gene silencing. Mol. Plant 2025, 18, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrich, P.; Rutter, B.D.; Karimi, H.Z.; Podicheti, R.; Meyers, B.C.; Innes, R.W. Plant Extracellular Vesicles Contain Diverse Small RNA Species and Are Enriched in 10- to 17-Nucleotide “Tiny” RNAs. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorin, D.N.; Eprintsev, A.T.; Chuykova, V.O.; Igamberdiev, A.U. Participation of miR165a in the Phytochrome Signal Transduction in Maize (Zea mays L.) Leaves under Changing Light Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Chen, B.; Jia, J.; Liu, J. Relationship between Protein, MicroRNA Expression in Extracellular Vesicles and Rice Seed Vigor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hou, D.; Chen, X.; Li, D.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Bian, Z.; Liang, X.; Cai, X.; et al. Exogenous plant MIR168a specifically targets mammalian LDLRAP1: Evidence of cross-kingdom regulation by microRNA. Cell Res. 2012, 22, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, S.; Romano, S.; Valentino, A.; Galderisi, U.; Peluso, G.; Calarco, A. Plant-Derived Exosomes: Carriers and Cargo of Natural Bioactive Compounds: Emerging Functions and Applications in Human Health. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Feng, S.; Wang, X.; Long, K.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J.; Tang, Q.; Jin, L.; Li, X.; et al. Identification of exosome-like nanoparticle-derived microRNAs from 11 edible fruits and vegetables. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.K.; Rhee, W.J. Antioxidative Effects of Carrot-Derived Nanovesicles in Cardiomyoblast and Neuroblastoma Cells. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Hou, L.; Cao, Y.; Li, M.; Sheng, X.; Cheng, W.; Yan, L.; Zheng, L. Tea Extracellular Vesicle-Derived MicroRNAs Contribute to Alleviate Intestinal Inflammation by Reprogramming Macrophages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 6745–6757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Z.; Yii, C.Y.; Yong, S.B.; Li, C.J. peu-MIR2916-p3-enriched garlic exosomes ameliorate murine colitis by reshaping gut microbiota, especially by boosting the anti-colitic Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron—Correspondence. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 202, 107131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.; Jeong, H.; Jang, E.; Kim, E.; Yoon, Y.; Jang, S.; Jeong, H.S.; Jang, G. Isolation of high-purity and high-stability exosomes from ginseng. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1064412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuela, N.; Muhammad, D.R.; Iriawati Wijaya, C.H.; Ratnadewi, Y.M.D.; Takemori, H.; Ana, I.D.; Yuniati, R.; Handayani, W.; Wungu, T.D.K.; Tabata, Y.; et al. Isolation of plant-derived exosome-like nanoparticles (PDENs) from Solanum nigrum L. berries and Their Effect on interleukin-6 expression as a potential anti-inflammatory agent. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.C.; Feinbaum, R.L.; Ambros, V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 1993, 75, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, B.J.; Weinstein, E.G.; Rhoades, M.W.; Bartel, B.; Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs in plants. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 1616–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, H.R.; Schoenfeld, L.W.; Ruby, J.G.; Auyeung, V.C.; Spies, N.; Baek, D.; Johnston, W.K.; Russ, C.; Luo, S.; Babiarz, J.E.; et al. Mammalian microRNAs: Experimental evaluation of novel and previously annotated genes. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 992–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.S.; Xie, Q.; Fei, J.F.; Chua, N.H. MicroRNA directs mRNA cleavage of the transcription factor NAC1 to downregulate auxin signals for arabidopsis lateral root development. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 1376–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaucheret, H.; Vazquez, F.; Crété, P.; Bartel, D.P. The action of ARGONAUTE1 in the miRNA pathway and its regulation by the miRNA pathway are crucial for plant development. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Kasschau, K.D.; Carrington, J.C. Negative feedback regulation of Dicer-Like1 in Arabidopsis by microRNA-guided mRNA degradation. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, J.L. Class III HD-Zip gene regulation, the golden fleece of ARGONAUTE activity? Bioessays 2004, 26, 938–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallory, A.C.; Dugas, D.V.; Bartel, D.P.; Bartel, B. MicroRNA regulation of NAC-domain targets is required for proper formation and separation of adjacent embryonic, vegetative, and floral organs. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H.; Seo, P.J.; Kang, S.K.; Park, C.M. miR172 signals are incorporated into the miR156 signaling pathway at the SPL3/4/5 genes in Arabidopsis developmental transitions. Plant Mol. Biol. 2011, 76, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poethig, R.S. Vegetative phase change and shoot maturation in plants. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2013, 105, 125–152. [Google Scholar]

- Sunkar, R.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, J.K. Identification of novel and candidate miRNAs in rice by high throughput sequencing. BMC Plant Biol. 2008, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Liang, R.; Ge, L.; Li, W.; Xiao, H.; Lin, H.; Ruan, K.; Jin, Y. Identification of drought-induced microRNAs in rice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 354, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, G.; Sutoh, K.; Zhu, J.K.; Zhang, W. Identification of cold-inducible microRNAs in plants by transcriptome analysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1779, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, S.; Park, G.; Atamian, H.S.; Han, C.S.; Stajich, J.E.; Kaloshian, I.; Borkovich, K.A. MicroRNAs suppress NB domain genes in tomato that confer resistance to Fusarium oxysporum. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallory, A.C.; Reinhart, B.J.; Bartel, D.; Vance, V.B.; Bowman, L.H. A viral suppressor of RNA silencing differentially regulates the accumulation of short interfering RNAs and micro-RNAs in tobacco. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 15228–15233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Quintero, Á.L.; Quintero, A.; Urrego, O.; Vanegas, P.; López, C. Bioinformatic identification of cassava miRNAs differentially expressed in response to infection by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. Manihotis. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Ding, H.; Qiu, M.; Xue, L.; Ge, D.; Wen, G.; Ren, H.; Li, P.; Wang, J. Applications of plant-derived extracellular vesicles in medicine. MedComm 2024, 5, e741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Rong, Y.; Teng, Y.; Mu, J.; Zhuang, X.; Tseng, M.; Samykutty, A.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Miller, D.; et al. Broccoli-Derived Nanoparticle Inhibits Mouse Colitis by Activating Dendritic Cell AMP-Activated Protein Kinase. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25, 1641–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, E.; Colosetti, P.; Jalabert, A.; Meugnier, E.; Wiklander, O.P.B.; Jouhet, J.; Errazurig-Cerda, E.; Chanon, S.; Gupta, D.; Rautureau, G.J.P.; et al. Use of Nanovesicles from Orange Juice to Reverse Diet-Induced Gut Modifications in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020, 18, 880–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, X.; Deng, Z.B.; Mu, J.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Miller, D.; Feng, W.; McClain, C.J.; Zhang, H.G. Ginger-derived nanoparticles protect against alcohol-induced liver damage. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 28713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, S.; Mu, J.; Dokland, T.; Zhuang, X.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, H.; Xiang, X.; Deng, Z.B.; Wang, B.; Zhang, L.; et al. Grape exosome-like nanoparticles induce intestinal stem cells and protect mice from DSS-induced colitis. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 1345–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Li, T.; Qi, W.; Miao, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, C.; Jin, H.; Pan, H.; Wang, D. Advances in the study of plant-derived extracellular vesicles in the skeletal muscle system. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 204, 107202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Zhuang, X.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, H.; Deng, Z.-B.; Wang, B.; Zhang, L.; Kakar, S.; Jun, Y.; Miller, D.; et al. Interspecies communication between plant and mouse gut host cells through edible plant derived exosome-like nanoparticles. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 1561–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranc, W.; Kaczmarek, M.; Kowalska, K.; Pieńkowski, W.; Ciesiółka, S.; Konwerska, A.; Mozdziak, P.; Brązert, M.; Jeseta, M.; Spaczyński, R.Z.; et al. Morphological characteristics, extracellular vesicle structure and stem-like specificity of human follicular fluid cell subpopulation during osteodifferentiation. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2025, 142, 104965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bağcı, C.; Sever-Bahcekapili, M.; Belder, N.; Bennett, A.P.S.; Erdener, Ş.E.; Dalkara, T. Overview of extracellular vesicle characterization techniques and introduction to combined reflectance and fluorescence confocal microscopy to distinguish extracellular vesicle subpopulations. Neurophotonics 2022, 9, 021903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuo, S.T.; Chien, J.C.; Lai, C.P. Imaging extracellular vesicles: Current and emerging methods. J. Biomed. Sci. 2018, 25, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Viennois, E.; Xu, C.; Merlin, D. Plant derived edible nanoparticles as a new therapeutic approach against diseases. Tissue Barriers 2016, 4, e1134415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woith, E.; Fuhrmann, G.; Melzig, M.F. Extracellular vesicles-connecting kingdoms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborowski, M.P.; Balaj, L.; Breakefield, X.O.; Lai, C.P. Extracellular Vesicles: Composition, Biological Relevance, and Methods of Study. Bioscience 2015, 65, 783–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamkovich, S.N.; Tutanov, O.S.; Laktionov, P.P. Exosomes: Generation, structure, transport, biological activity, and diagnostic application. Biol. Membr. 2016, 33, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Tyler, B.M. Biogenesis and Biological Functions of Extracellular Vesicles in Cellular and Organismal Communication With Microbes. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 817844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Gao, J.; He, Y.; Jiang, L. Plant extracellular vesicles. Protoplasma 2020, 257, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nueraihemaiti, N.; Dilimulati, D.; Baishan, A.; Hailati, S.; Maihemuti, N.; Aikebaier, A.; Paerhati, Y.; Zhou, W. Advances in Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicle Extraction Methods and Pharmacological Effects. Biology 2025, 14, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkocak, D.C.; Phan, T.K.; Poon, I.K.H. Translating extracellular vesicle packaging into therapeutic applications. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 946422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Apoplastic Proteases: Powerful Weapons against Pathogen Infection in Plants. Plant Commun. 2020, 1, 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.B.; Deng, X.; Shen, L.S.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Ye, L.; Chen, S.; Yang, D.J.; Chen, G.Q. Advances in plant-derived extracellular vesicles: Isolation, composition, and biological functions. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 11319–11341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, A.C.; Dawson, T.R.; Di Vizio, D.; Weaver, A.M. Context-specific regulation of extracellular vesicle biogenesis and cargo selection. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 454–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiner, E.; Berryman, E.; Frey, F.; Solís, A.G.; Leier, A.; Lago, T.M.; Šarić, A.; Otegui, M.S. Endosomal membrane budding patterns in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2409407121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, E.; Berryman, E.; González Solís, A.; Shi, Y.; Otegui, M.S. The green ESCRTs: Newly defined roles for ESCRT proteins in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Solís, A.; Berryman, E.; Otegui, M.S. Plant endosomes as protein sorting hubs. FEBS Lett. 2022, 596, 2288–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurley, J.H.; Hanson, P.I. Membrane budding and scission by the ESCRT machinery: It’s all in the neck. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, S.; Macheboeuf, P.; Martinelli, N.; Weissenhorn, W. Divergent pathways lead to ESCRT-III-catalyzed membrane fission. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011, 36, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayers, J.R.; Fyfe, I.; Schuh, A.L.; Chapman, E.R.; Edwardson, J.M.; Audhya, A. ESCRT-0 assembles as a heterotetrameric complex on membranes and binds multiple ubiquitinylated cargoes simultaneously. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 9636–9645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.W.; Sung, H.; Shin, D.; Shen, H.; Ahnn, J.; Lee, S.K.; Lee, S. Differential physiological roles of ESCRT complexes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Cells 2011, 31, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azmi, I.; Davies, B.; Dimaano, C.; Payne, J.; Eckert, D.; Babst, M.; Katzmann, D.J. Recycling of ESCRTs by the AAA-ATPase Vps4 is regulated by a conserved VSL region in Vta1. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 172, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.E.; Scruggs, B.S.; Schaffer, J.E.; Hanson, P.I. Effects of Inhibiting VPS4 Support a General Role for ESCRTs in Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis. Biophys. J. 2017, 113, 1342–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zhuang, X.; Cui, Y.; Fu, X.; He, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Shen, J.; Luo, M.; Jiang, L. Dual roles of an Arabidopsis ESCRT component FREE1 in regulating vacuolar protein transport and autophagic degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 1886–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Luo, M.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, R.; Cui, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Xia, J.; Jiang, L. A unique plant ESCRT component, FREE1, regulates multivesicular body protein sorting and plant growth. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, 2556–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.G.; Neuhaus, J.M. Receptor-mediated sorting of soluble vacuolar proteins: Myths, facts, and a new model. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 4435–4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Stierhof, Y.D.; Robinson, D.G.; Jiang, L. Unconventional protein secretion. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, B.D.; Innes, R.W. Extracellular vesicles isolated from the leaf apoplast carry stress-response proteins. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 728–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, B.L.; Rutter, B.D.; Borniego, M.L.; Singla-Rastogi, M.; Gardner, D.M.; Innes, R.W. Arabidopsis Produces Distinct Subpopulations of Extracellular Vesicles That Respond Differentially to Biotic Stress, Altering Growth and Infectivity of a Fungal Pathogen. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2025, 14, e70090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D.; Pajonk, S.; Micali, C.; O’Connell, R.; Schulze-Lefert, P. Extracellular transport and integration of plant secretory proteins into pathogen-induced cell wall compartments. Plant J. 2009, 57, 986–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Huang, J.; Cao, Y.; Gao, Z. The resistance associated protein RIN4 promotes the extracellular transport of AtEXO70E2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 555, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecenková, T.; Hála, M.; Kulich, I.; Kocourková, D.; Drdová, E.; Fendrych, M.; Toupalová, H.; Zársky, V. The role for the exocyst complex subunits Exo70B2 and Exo70H1 in the plant-pathogen interaction. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 2107–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortmannová, J.; Sekereš, J.; Kulich, I.; Šantrůček, J.; Dobrev, P.; Žárský, V.; Pečenková, T. Arabidopsis EXO70B2 exocyst subunit contributes to papillae and encasement formation in antifungal defence. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Blache, A.; Achouak, W. Insights into Bacterial Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis, Functions, and Implications in Plant-Microbe Interactions. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillada, C.; Rojas-Pierce, M. Vacuolar trafficking and biogenesis: A maturation in the field. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 40, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paez Valencia, J.; Goodman, K.; Otegui, M.S. Endocytosis and Endosomal Trafficking in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2016, 67, 309–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Bao, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, M.; Fan, B.; Zhu, C.; Chen, Z. Biogenesis and Function of Multivesicular Bodies in Plant Immunity. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maricchiolo, E.; Panfili, E.; Pompa, A.; De Marchis, F.; Bellucci, M.; Pallotta, M.T. Unconventional Pathways of Protein Secretion: Mammals vs. Plants. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 895853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, S.; Carata, E.; Muci, M.; Mariano, S.; Panzarini, E. Impact of hypoxia on the molecular content of glioblastoma-derived exosomes. Extracell. Vesicles Circ. Nucl. Acids 2024, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hu, J.; Zhong, H.; Wu, Q.; Fang, Z.; Cai, Y.; Huang, P.; Abubakar, Y.S.; Zhou, J.; Naqvi, N.I.; et al. Vacuolar recruitment of retromer by a SNARE complex enables infection-related trafficking in rice blast. New Phytol. 2024, 244, 997–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madina, M.H.; Rahman, M.S.; Zheng, H.; Germain, H. Vacuolar membrane structures and their roles in plant–pathogen interactions. Plant Mol. Biol. 2019, 101, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, T.; Han, J.; Li, M.; Zhao, Y.; Su, T.; Ma, C. Plant Autophagy: An Intricate Process Controlled by Various Signaling Pathways. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 754982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, R.; Zhuang, X. Multifaceted Roles of the ATG8 Protein Family in Plant Autophagy: From Autophagosome Biogenesis to Cargo Recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 2025, 437, 168981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosesso, N.; Lerner, N.S.; Bläske, T.; Groh, F.; Maguire, S.; Niedermeier, M.L.; Landwehr, E.; Vogel, K.; Meergans, K.; Nagel, M.K.; et al. Arabidopsis CaLB1 undergoes phase separation with the ESCRT protein ALIX and modulates autophagosome maturation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldolesi, J. Unconventional Protein Secretion Dependent on Two Extracellular Vesicles: Exosomes and Ectosomes. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 877344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Qu, Z.; He, Y.; Han, Y.; Xing, Y.; Liu, S.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Extracellular vesicle GABA responds to cadmium stress, and GAD overexpression alleviates cadmium damage in duckweed. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1536786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Pych, E.; Whitehead, B.J.; Nejsum, P.L.; Bellini, I.; Drace, T.; Boesen, T.; Paponov, I.; Rasmussen, M.K. Impact of abiotic stress on miRNA profiles in tomato-derived extracellular vesicles and their biological activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 319, 145260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegstra, K. Plant Cell Walls. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, M.; Rose, J. Blueprint for building plant cell walls. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chapple, C. Understanding lignification: Challenges beyond monolignol biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpita, N.; Sabularse, D.; Montezinos, D.; Delmer, D.P. Determination of the pore size of cell walls of living plant cells. Science 1979, 205, 1144–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleischer, A.; O’Neill, M.A.; Ehwald, R. The Pore Size of Non-Graminaceous Plant Cell Walls Is Rapidly Decreased by Borate Ester Cross-Linking of the Pectic Polysaccharide Rhamnogalacturonan II. Plant Physiol. 1999, 121, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruf, A.; Oberkofler, L.; Robatzek, S.; Weiberg, A. Spotlight on plant RNA-containing extracellular vesicles. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2022, 69, 102272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocholata, M.; Prusova, M.; Auer Malinska, H.; Maly, J.; Janouskova, O. Comparison of two isolation methods of tobacco-derived extracellular vesicles, their characterization and uptake by plant and rat cells. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Bai, C.; Liu, X.; Gao, Y. Ginger-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: A Natural Solution for Alopecia. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2024, 23, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Feng, J.; Jin, A.; Shao, Y.; Shen, M.; Ma, J.; Lei, L.; Liu, L. Extracellular Vesicles for Disease Treatment. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 3303–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Cai, X.; Wu, Q.; Liao, H.; Liang, S.; Fu, H.; Xiang, Q.; Zhang, S. Extraction, Isolation, and Component Analysis of Turmeric-Derived Exosome-like Nanoparticles. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaynab, M.; Fatima, M.; Abbas, S.; Sharif, Y.; Umair, M.; Zafar, M.H.; Bahadar, K. Role of secondary metabolites in plant defense against pathogens. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 124, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, G.; Logozzi, M.; Mizzoni, D.; Di Raimo, R.; Cerio, A.; Dolo, V.; Pasquini, L.; Screnci, M.; Ottone, T.; Testa, U.; et al. Ex Vivo Anti-Leukemic Effect of Exosome-like Grapefruit-Derived Nanovesicles from Organic Farming-The Potential Role of Ascorbic Acid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajik, T.; Baghaei, K.; Moghadam, V.E.; Farrokhi, N.; Salami, S.A. Extracellular vesicles of cannabis with high CBD content induce anticancer signaling in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 152, 113209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perut, F.; Roncuzzi, L.; Avnet, S.; Massa, A.; Zini, N.; Sabbadini, S.; Giampieri, F.; Mezzetti, B.; Baldini, N. Strawberry-Derived Exosome-Like Nanoparticles Prevent Oxidative Stress in Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shkryl, Y.; Tsydeneshieva, Z.; Menchinskaya, E.; Rusapetova, T.; Grishchenko, O.; Mironova, A.; Bulgakov, D.; Gorpenchenko, T.; Kazarin, V.; Tchernoded, G.; et al. Exosome-like Nanoparticles, High in Trans-δ-Viniferin Derivatives, Produced from Grape Cell Cultures: Preparation, Characterization, and Anticancer Properties. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocsfalvi, G.; Turiak, L.; Ambrosone, A.; Del Gaudio, P.; Puska, G.; Fiume, I.; Silvestre, T.; Vekey, K. Protein biocargo of citrus fruit-derived vesicles reveals heterogeneous transport and extracellular vesicle populations. J. Plant Physiol. 2018, 229, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Palma, M.; Ambrosone, A.; Leone, A.; Del Gaudio, P.; Ruocco, M.; Turiak, L.; Bokka, R.; Fiume, I.; Tucci, M.; Pocsfalvi, G. Plant Roots Release Small Extracellular Vesicles with Antifungal Activity. Plants 2020, 9, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Tao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, T.; Wang, H.; Mu, J.; Wu, Y.; He, Z.; Zhang, C.; Lunter, D.J.; et al. Perilla frutescens Leaf-Derived Extracellular Vesicle-Like Particles Carry Pab-miR-396a-5p to Alleviate Psoriasis by Modulating IL-17 Signaling. Research 2025, 8, 0675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhan, H.; Lv, S.; Luo, Y.; Wang, W.; Hu, X. Integrating proteomic and phosphoproteomic profiles provide new insights into ABA-dependent signal regulation network in maize response to heat stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Song, C.; Fang, S.; Wei, Y.; Tian, J.; Zheng, X.; Jiao, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, K.; Hao, P.; et al. Systematic identification and analysis of the HSP70 genes reveals MdHSP70-38 enhanced salt tolerance in transgenic tobacco and apple. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 289, 138943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantila, A.Y.; Chen, S.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Cowling, W.A. Heat shock responsive genes in Brassicaceae: Genome-wide identification, phylogeny, and evolutionary associations within and between genera. Genome 2024, 67, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa-Fernandes, L.; Rocha, V.B.; Carregari, V.C.; Urbani, A.; Palmisano, G. A Perspective on Extracellular Vesicles Proteomics. Front. Chem. 2017, 5, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Cai, Q.; Qiao, L.; Huang, C.Y.; Wang, S.; Miao, W.; Ha, T.; Wang, Y.; Jin, H. RNA-binding proteins contribute to small RNA loading in plant extracellular vesicles. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegler, J.L.; Grof, C.P.L.; Eamens, A.L. The Plant microRNA Pathway: The Production and Action Stages. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1932, 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pegler, J.L.; Oultram, J.M.J.; Grof, C.P.L.; Eamens, A.L. The Use of Arabidopsis thaliana to Characterize the Production and Action Stages of the Plant MicroRNA Pathway. In Plant MicroRNAs: Methods and Protocols; Spring: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Volume 2900, pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Bian, Y.; Ren, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhou, F.; Ding, H. A critical review on plant annexin: Structure, function, and mechanism. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 190, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, C.; Zhu, J.; Zhong, S.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, X. Functions and mechanisms of RNA helicases in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 2295–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, F.; Ladera-Carmona, M.J.; Weits, D.A.; Ferri, G.; Iacopino, S.; Novi, G.; Svezia, B.; Kunkowska, A.B.; Santaniello, A.; Piaggesi, A.; et al. Exogenous miRNAs induce post-transcriptional gene silencing in plants. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 1379–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhogale, S.; Mahajan, A.S.; Natarajan, B.; Rajabhoj, M.; Thulasiram, H.V.; Banerjee, A.K. MicroRNA156: A potential graft-transmissible microRNA that modulates plant architecture and tuberization in Solanum tuberosum ssp. andigena. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 1011–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Park, M.Y.; Conway, S.R.; Wang, J.W.; Weigel, D.; Poethig, R.S. The sequential action of miR156 and miR172 regulates developmental timing in Arabidopsis. Cell 2009, 138, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, R.; Datt Pant, B.; Stitt, M.; Scheible, W.R. PHO2, microRNA399, and PHR1 define a phosphate-signaling pathway in plants. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 988–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, B.D.; Buhtz, A.; Kehr, J.; Scheible, W.R. MicroRNA399 is a long-distance signal for the regulation of plant phosphate homeostasis. Plant J. 2008, 53, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Xu, X.; Xiong, F. miRNA in Regulating Seed Development and the Response to Abiotic Stress in Plant: A Review. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2023, 39, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, P.; Wu, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Chen, Z. OsmiR5519 regulates grain size and weight and down-regulates sucrose synthase gene RSUS2 in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Planta 2024, 259, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Li, M.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fang, Y. Coordinated regulation of Arabidopsis microRNA biogenesis and red light signaling through Dicer-like 1 and phytochrome-interacting factor 4. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; He, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Li, L.; Deng, X.W. Genome-wide mapping of the HY5-mediated gene networks in Arabidopsis that involve both transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation. Plant J. 2011, 65, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, E.; Al-Sady, B.; Quail, P.H. Nuclear translocation of the photoreceptor phytochrome B is necessary for its biological function in seedling photomorphogenesis. Plant J. 2003, 35, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, I.C.; Henriques, R.; Seo, H.S.; Nagatani, A.; Chua, N.H. Arabidopsis PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR proteins promote phytochrome B polyubiquitination by COP1 E3 ligase in the nucleus. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 2370–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Yuan, Z.; Li, F.; Yang, L.; Huang, H. Two types of cis-acting elements control the abaxial epidermis-specific transcription of the MIR165a and MIR166a genes. FEBS Lett. 2009, 583, 3711–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Q.; He, B.; Wang, S.; Fletcher, S.; Niu, D.; Mitter, N.; Birch, P.R.J.; Jin, H. Message in a Bubble: Shuttling Small RNAs and Proteins Between Cells and Interacting Organisms Using Extracellular Vesicles. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2021, 72, 497–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhu, X.; Tang, G.; Bressan, R.A.; Zhu, J.K. The miR165/166 Mediated Regulatory Module Plays Critical Roles in ABA Homeostasis and Response in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Wang, Y.; Teotia, S.; Wang, Z.; Shi, C.; Sun, H.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, G. The interaction between miR160 and miR165/166 in the control of leaf development and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, Y.S.; Sadiq, I.Z.; Aarti, A.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, W. Interplay of Transport Vesicles during Plant-Fungal Pathogen Interaction. Stress Biol. 2023, 3, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.P.; Kwon, S.; Adeshara, T.; Göhre, V.; Feldbrügge, M.; Weiberg, A. Extracellular RNAs Released by Plant-Associated Fungi: From Fundamental Mechanisms to Biotechnological Applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 5935–5945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Wang, H.; Liu, G.; Chen, A.; Calvo, A.; Cai, Q.; Jin, H. Fungal small RNAs ride in extracellular vesicles to enter plant cells through clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; O’Connell, R.; Maekawa-Yoshikawa, M.; Uemura, T.; Neumann, U.; Schulze-Lefert, P. The powdery mildew resistance protein RPW8.2 is carried on VAMP721/722 vesicles to the extrahaustorial membrane of haustorial complexes. Plant J. 2014, 79, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Van Bel, A.J.E.; Hückelhoven, R. Do Plant Cells Secrete Exosomes Derived from Multivesicular Bodies? Plant Signal. Behav. 2007, 2, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sattar, S.; Addo-Quaye, C.; Song, Y.; Anstead, J.A.; Sunkar, R.; Thompson, G.A. Expression of small RNA in Aphis gossypii and its potential role in the resistance interaction with melon. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, C.; Dou, Y.; Yu, B.; Liu, Y.; Heng-Moss, T.M.; Lu, G.; Wachholtz, M.; Bradshaw, J.D.; Twigg, P.; et al. Insect and plant-derived miRNAs in greenbug (Schizaphis graminum) and yellow sugarcane aphid (Sipha flava) revealed by deep sequencing. Gene 2017, 599, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, L.; Zhang, D.; Xiang, Z.; He, N. Nonfunctional ingestion of plant miRNAs in silkworm revealed by digital droplet PCR and transcriptome analysis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.L.; Jing, X.D.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.; Lin, J.H.; Zheng, L.; Dong, Y.H.; Zhou, L.; Li, F.F.; Yang, F.Y.; et al. Host Plant-Derived miRNAs Potentially Modulate the Development of a Cosmopolitan Insect Pest, Plutella xylostella. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, J.W.; Hale, A.E.; Isaacs, S.K.; Baggish, A.L.; Chan, S.Y. Ineffective delivery of diet-derived microRNAs to recipient animal organisms. RNA Biol. 2013, 10, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, M.; Everett, C.P.; Chan, S.Y.; Snow, J.W. Negligible uptake and transfer of diet-derived pollen microRNAs in adult honey bees. RNA Biol. 2016, 13, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhao, Y.L.; Zhao, J.H.; Wang, S.; Jin, Y.; Chen, Z.Q.; Fang, Y.Y.; Hua, C.L.; Ding, S.W.; Guo, H.S. Cotton plants export microRNAs to inhibit virulence gene expression in a fungal pathogen. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 16153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, J.; Peng, D. Wheat microRNA1023 suppresses invasion of Fusarium graminearum via targeting and silencing FGSG_03101. J. Plant Interact. 2018, 13, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiberg, A.; Wang, M.; Lin, F.M.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Kaloshian, I.; Huang, H.D.; Jin, H. Fungal small RNAs suppress plant immunity by hijacking host RNA interference pathways. Science 2013, 342, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Jin, W.; Wu, F. Novel tomato miRNA miR1001 initiates cross-species regulation to suppress the conidiospore germination and infection virulence of Botrytis cinerea in vitro. Gene 2020, 759, 145002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Peragine, A.; Park, M.Y.; Poethig, R.S. A pathway for the biogenesis of trans-acting siRNAs in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 2164–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Feng, L.; Karimi, H.Z.; Rutter, B.D.; Zeng, L.; Choi, D.S.; Zhang, B.; Gu, W.; Chen, X.; et al. A Phytophthora Effector Suppresses Trans-Kingdom RNAi to Promote Disease Susceptibility. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petre, B.; Kamoun, S. How do filamentous pathogens deliver effector proteins into plant cells? PLoS Biol. 2014, 12, e1001801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Sun, X.; Xu, M.; Tian, Z. Identification of miRNAs Involving Potato-Phytophthora infestans Interaction. Plants 2023, 12, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.M.; Chng, C.P.; Pu, X.; Ma, Z.; Han, X.; Liu, X.; Yang, L.; Huang, C.; Miao, Y. Potentiation of plant defense by bacterial outer membrane vesicles is mediated by membrane nanodomains. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Rupp, O.; Brachmann, A.; Blum, C.F.; Kraege, A.; Goesmann, A.; Feldbrügge, M. mRNA Inventory of Extracellular Vesicles from Ustilago maydis. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Ceron, D.; Lowe, R.G.T.; McKenna, J.A.; Brain, L.M.; Dawson, C.S.; Clark, B.; Berkowitz, O.; Faou, P.; Whelan, J.; Bleackley, M.R.; et al. Extracellular vesicles from fusarium graminearum contain protein effectors expressed during infection of corn. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleackley, M.R.; Samuel, M.; Garcia-Ceron, D.; McKenna, J.A.; Lowe, R.G.T.; Pathan, M.; Zhao, K.; Ang, C.S.; Mathivanan, S.; Anderson, M.A. Extracellular vesicles from the cotton pathogen Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum induce a phytotoxic response in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez Rodriguez, M.C.; Petersen, M.; Mundy, J. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 621–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Sun, Y.; Song, N.; Zhao, M.; Liu, R.; Feng, H.; Wang, X.; Kang, Z. Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici microRNA-like RNA 1 (Pst-milR1), an important pathogenicity factor of Pst, impairs wheat resistance to Pst by suppressing the wheat pathogenesis-related 2 gene. New Phytol. 2017, 215, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunker, F.; Trutzenberg, A.; Rothenpieler, J.S.; Kuhn, S.; Pröls, R.; Schreiber, T.; Tissier, A.; Kemen, A.; Kemen, E.; Hückelhoven, R.; et al. Oomycete small RNAs bind to the plant RNA-induced silencing complex for virulence. Elife 2020, 9, e56096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Validov, S.Z.; Kamilova, F.D.; Lugtenberg, B.J.J. Monitoring of pathogenic and non-pathogenic Fusarium oxysporum strains during tomato plant infection. Microb. Biotechnol. 2011, 4, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.M.; Mao, H.Y.; Li, S.J.; Feng, T.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Cheng, L.; Luo, S.J.; Borkovich, K.A.; Ouyang, S.Q. Fol-milR1, a pathogenicity factor of Fusarium oxysporum, confers tomato wilt disease resistance by impairing host immune responses. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.S.; Li, Y.C.; Guo, H.S.; Zhao, J.H. Verticillium dahliae Secretes Small RNA to Target Host MIR157d and Retard Plant Floral Transition During Infection. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 847086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Xu, M.; Willmann, M.R.; McCormick, K.; Hu, T.; Yang, L.; Starker, C.G.; Voytas, D.F.; Meyers, B.C.; Poethig, R.S. Threshold-dependent repression of SPL gene expression by miR156/miR157 controls vegetative phase change in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Hu, T.; Poethig, R.S. Low light intensity delays vegetative phase change. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 1177–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Põlme, S.; Kõljalg, U.; Yorou, N.S.; Wijesundera, R.; Ruiz, L.V.; Vasco-Palacios, A.M.; Thu, P.Q.; Suija, A.; et al. Fungal biogeography. Global diversity and geography of soil fungi. Science 2014, 346, 1256688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrin, C.; Daguerre, Y.; Ruytinx, J.; Guinet, F.; Kemppainen, M.; Frey, N.F.D.; Puech-Pagès, V.; Hecker, A.; Pardo, A.G.; Martin, F.M.; et al. Laccaria bicolor MiSSP8 is a small-secreted protein decisive for the establishment of the ectomycorrhizal symbiosis. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 3765–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, V.; Simon, S.A.; Demirci, F.; Nakano, M.; Meyers, B.C.; Donofrio, N.M. Small RNA functions are required for growth and development of Magnaporthe oryzae. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2017, 30, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong-Bajracharya, J.; Singan, V.R.; Monti, R.; Plett, K.L.; Ng, V.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Martin, F.M.; Anderson, I.C.; Plett, J.M. The ectomycorrhizal fungus Pisolithus microcarpus encodes a microRNA involved in cross-kingdom gene silencing during symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2103527119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, M.; Banerjee, S.; Surana, P.; Liu, M.; Fuerst, G.; Mathioni, S.; Meyers, B.C.; Nettleton, D.; Wise, R.P. Small RNA discovery in the interaction between barley and the powdery mildew pathogen. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kusch, S.; Singh, M.; Thieron, H.; Spanu, P.D.; Panstruga, R. Site-specific analysis reveals candidate cross-kingdom small RNAs, tRNA and rRNA fragments, and signs of fungal RNA phasing in the barley-powdery mildew interaction. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2023, 24, 570–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, S.; Kim, G.; Johnson, N.R.; Wafula, E.; Wang, F.; Coruh, C.; Bernal-Galeano, V.; Phifer, T.; dePamphilis, C.W.; Westwood, J.H.; et al. MicroRNAs from the parasitic plant Cuscuta campestris target host messenger RNAs. Nature 2018, 553, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Felippes, F.F.; Waterhouse, P.M. The Whys and Wherefores of Transitivity in Plants. Front Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 579376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malka, O.; Santos-Garcia, D.; Feldmesser, E.; Sharon, E.; Krause-Sakate, R.; Delatte, H.; van Brunschot, S.; Patel, M.; Visendi, P.; Mugerwa, H.; et al. Species-complex diversification and host-plant associations in Bemisia tabaci: A plant-defence, detoxification perspective revealed by RNA-Seq analyses. Mol. Ecol. 2018, 27, 4241–4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, S.; Atkinson, P.W.; Walling, L.L. Whitefly-plant interactions: An integrated molecular perspective. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2024, 69, 503–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Q.; Zhai, K.; Yang, D.; Yang, W.; Wu, J.; Liu, J.; Pan, W.; Wang, J.; Zhu, X.; Jian, Y.; et al. An E3 ubiquitin ligase-BAG protein module controls plant innate immunity and broad-spectrum disease resistance. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaeva, L.; Tolstyko, E.; Putevich, E.; Kil, Y.; Spitsyna, A.; Emelianova, S.; Solianik, A.; Yastremsky, E.; Garmay, Y.; Komarova, E.; et al. Microalgae-Derived Vesicles: Natural Nanocarriers of Exogenous and Endogenous Proteins. Plants 2025, 14, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pernice, M.C.; Closa, D.; Garcés, E. Cryo-electron microscopy of extracellular vesicles associated with the marine toxic dinoflagellate Alexandrium minutum. Harmful Algae 2023, 123, 102389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Hu, Z.; Yan, X.; Lu, J.; Wang, C. Extracellular vesicles involved in growth regulation and metabolic modulation in Haematococcus pluvialis. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2024, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamo, G.; Fierli, D.; Romancino, D.P.; Picciotto, S.; Barone, M.E.; Aranyos, A.; Božič, D.; Morsbach, S.; Raccosta, S.; Stanly, C. Nanoalgosomes: Introducing extracellular vesicles produced by microalgae. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhu, R.; Chen, Z.; Du, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, C.; Jiang, P.; Luo, Y.; Lei, A.; Liu, Q. Extracellular vesicles in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: Mediators of nutrient sensing and cell-to-cell communication. Algal Res. 2025, 85, 103853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, B.; Chung, H.; Jung, H.; Song, H.-K.; Park, E.; Choi, H.S.; Jung, K.; Choe, H.; Yang, S.; Oh, E.-S. Extracellular vesicles from Korean Codium fragile and Sargassum fusiforme negatively regulate melanin synthesis. Mol. Cells 2021, 44, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, F.; Afshar, A.; Baghban, N. Algal cells-derived extracellular vesicles: A review with special emphasis on their antimicrobial effects. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 785716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voshall, A.; Kim, E.J.; Ma, X.; Yamasaki, T.; Moriyama, E.N.; Cerutti, H. miRNAs in the alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii are not phylogenetically conserved and play a limited role in responses to nutrient deprivation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.; Zhao, M.; Campbell, A.H.; Paul, N.A.; Cummins, S.F.; Eamens, A.L. The microRNA Pathway of Macroalgae: Its Similarities and Differences to the Plant and Animal microRNA Pathways. Genes 2025, 16, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Xu, Z.; Cai, C.; Liao, Y.; Yang, C.; Du, X.; Huang, R.; Deng, Y. Circulating exosome miRNA, is it the novel nutrient molecule through cross-kingdom regulation mediated by food chain transmission from microalgae to bivalve? Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 2022, 43, 101004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, L.; Lan, C.; Capriotti, L.; Ah-Fong, A.; Nino Sanchez, J.; Hamby, R.; Heller, J.; Zhao, H.; Glass, N.L.; Judelson, H.S.; et al. Spray-Induced Gene Silencing for Disease Control Is Dependent on the Efficiency of Pathogen RNA Uptake. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1756–1768. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, M.; Raposo, G.; Thery, C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 30, 255–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, S.; Koo, Y.; Yang, A.; Dai, Y.; Khant, H.; Osman, S.R.; Chowdhury, M.; Wei, H.; Li, Y.; et al. Characterization of and isolation methods for plant leaf nanovesicles and small extracellular vesicles. Nanomedicine 2020, 29, 102271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delaunois, B.; Colby, T.; Belloy, N.; Conreux, A. Large-Scale Proteomic Analysis of the Grapevine Leaf Apoplastic Fluid Reveals Mainly Stress-Related Proteins and CellWall Modifying Enzymes. BMC Plant Biol. 2013, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitter, N.; Worrall, E.A.; Robinson, K.E.; Li, P.; Jain, R.G.; Taochy, C.; Fletcher, S.J.; Carroll, B.J.; Lu, G.Q.; Xu, Z.P. Clay Nanosheets for Topical Delivery of RNAi for Sustained Protection against Plant Viruses. Nat. Plants 2017, 3, 16207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šečić, E.; Kogel, K.H. Requirements for fungal uptake of dsRNA and gene silencing in RNAi-based crop protection strategies. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2021, 70, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, L.; Nino-Sánchez, J.; Hamby, R.; Capriotti, L.; Chen, A.; Mezzetti, B.; Jin, H. Artificial Nanovesicles for dsRNA Delivery in Spray Induced Gene Silencing for Crop Protection. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 854–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Q.W.; Lin, S.S.; Reyes, J.L.; Chen, K.C.; Wu, H.W.; Yeh, S.D.; Chua, N.H. Expression of artificial microRNAs in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana confers virus resistance. Nat Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, T.; Zhang, L.; Gao, Z.; Zhu, C.X.; Guo, X. Highly efficient virus resistance mediated by artificial microRNAs that target the suppressor of PVX and PVY in plants. Plant Biol. 2011, 13, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Gong, P.; Ziaf, K.; Xiao, F.; Ye, Z. Expression of artificial microRNAs in tomato confers efficient and stable virus resistance in a cell-autonomous manner. Transgenic Res. 2011, 20, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Wei, J.; Lin, Y.; Chen, H. Gene silencing using the recessive rice bacterial blight resistance gene xa13 as a new paradigm in plant breeding. Plant Cell Rep. 2012, 31, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Weng, Z.; Li, H.; Kong, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Li, F.; Ma, W.; Lin, Y.; Chen, H. Transgenic rice overexpressing insect endogenous microRNA csu-novel-260 is resistant to striped stem borer under field conditions. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 421–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Wu, H.; Liu, H.; Zheng, J.; Lin, Y.; Chen, H. The overexpression of insect endogenous small RNAs in transgenic riceinhibits growth and delays pupation of striped stem borer (Chilo suppressalis). Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Xiao, H.; Sun, Y.; Ding, S.; Situ, G.; Li, F. Transgenic microRNA-14 rice shows high resistance to rice stem borer. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Rajamani, V.; Reddy, V.S.; Mukherjee, S.K.; Bhatnagar, R.K. Transgenic plants over-expressing insect-specific microRNA acquire insecticidal activity against Helicoverpa armigera: An alternative to Bt-toxin technology. Transgenic Res. 2015, 24, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogindran, S.; Rajam, M.V. Host-derived artificial miRNA-mediated silencing of ecdysone receptor gene provides enhanced resistance to Helicoverpa armigera in tomato. Genomics 2021, 113, 736–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shalvina, A.; Paul, N.A.; Cummins, S.F.; Eamens, A.L. Plant Extracellular Vesicles with Complex Molecular Cargo: A Cross-Kingdom Conduit for MicroRNA-Directed RNA Silencing. Genes 2026, 17, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010052

Shalvina A, Paul NA, Cummins SF, Eamens AL. Plant Extracellular Vesicles with Complex Molecular Cargo: A Cross-Kingdom Conduit for MicroRNA-Directed RNA Silencing. Genes. 2026; 17(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleShalvina, Ashmeeta, Nicholas A. Paul, Scott F. Cummins, and Andrew L. Eamens. 2026. "Plant Extracellular Vesicles with Complex Molecular Cargo: A Cross-Kingdom Conduit for MicroRNA-Directed RNA Silencing" Genes 17, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010052

APA StyleShalvina, A., Paul, N. A., Cummins, S. F., & Eamens, A. L. (2026). Plant Extracellular Vesicles with Complex Molecular Cargo: A Cross-Kingdom Conduit for MicroRNA-Directed RNA Silencing. Genes, 17(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010052