3.1. Differential Gene Expression and IPA Analysis

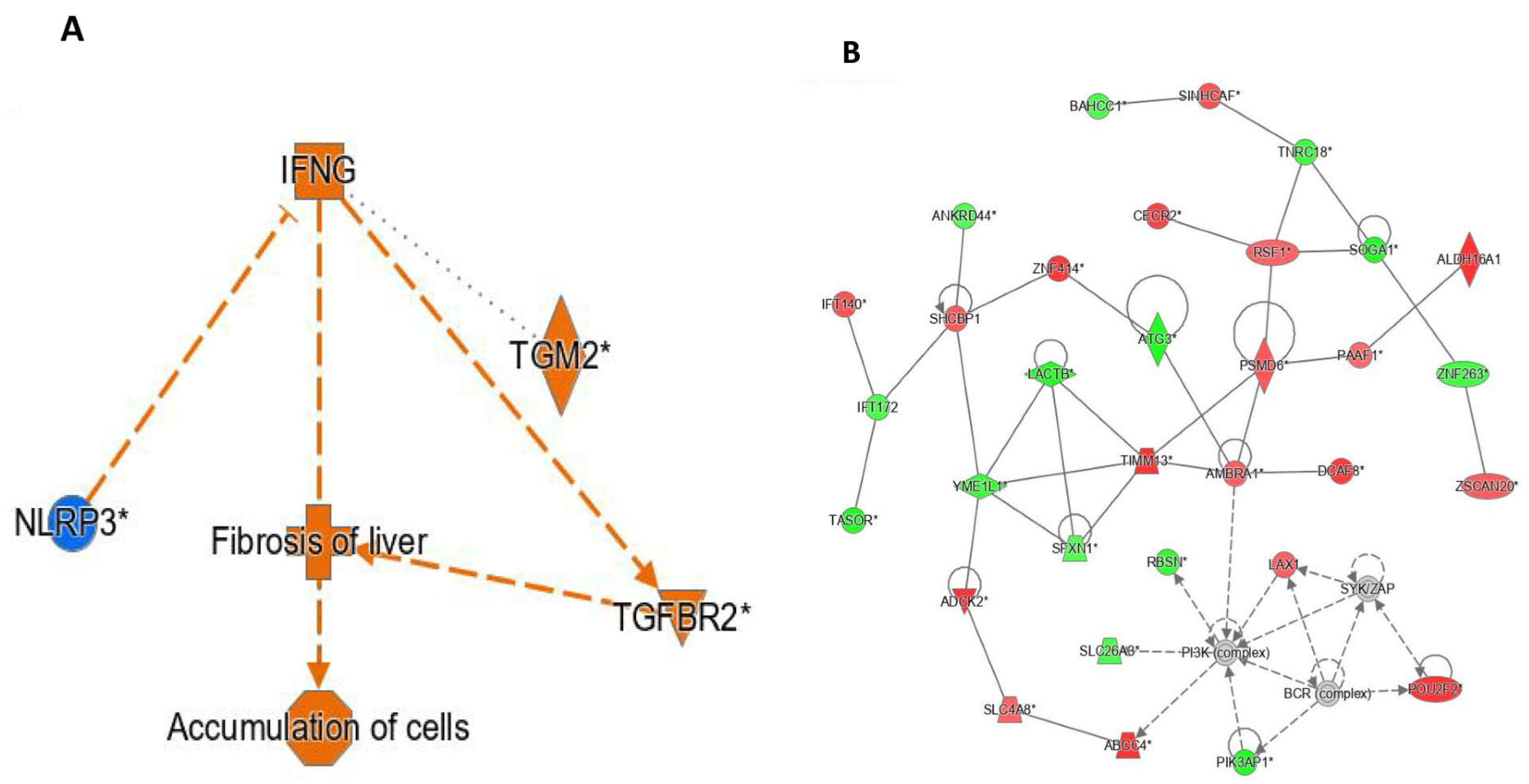

Figure 2A demonstrates the interplay between the differentially expressed (DE) pathways, liver fibrosis, and genes after pioglitazone exposure, namely

IFNG,

NLRP3, and

TGFBR2. All proteins in the pathway were predicted to be activated upon exposure to pioglitazone.

Figure 2B demonstrates the results of an interaction network analysis of the DE genes after pioglitazone exposure. Interestingly,

PSMD6 and

AMBRA1 showed the highest number of interactions with other DE genes after pioglitazone exposure (

p < 0.05). A graphical summary shows the interaction among immune pathways and cytokines, including

IFNG (interferon-γ), which was overexpressed after pioglitazone exposure (logFC = 1.2,

p < 0.05), and

TGFBR2 (transforming growth factor beta receptor II), which was also overexpressed (logFC = 0.218,

p < 0.05). Overall, these findings indicate that pioglitazone treatment is associated with coordinated regulation of immune-related and fibrosis-associated signalling pathways within the skeletal muscle interaction network.

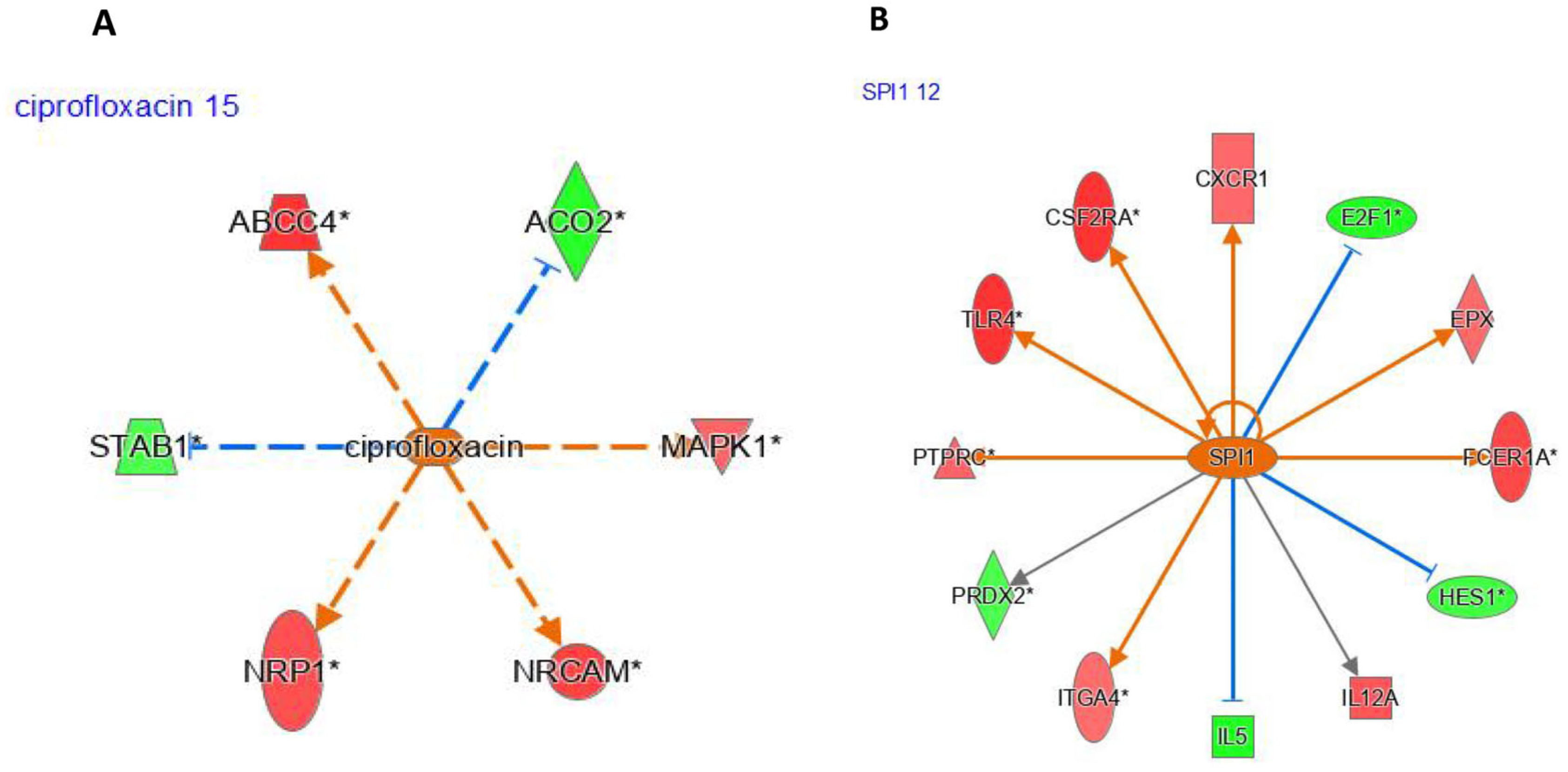

IPA-Upstream Regulators networks

Ciprofloxacin was identified by IPA as an upstream regulator (UR) affected by five genes via indirect interactions (

Figure 3A). Likewise, SPI1 (

Figure 3B) was predicted to be activated and was also identified as a UR by IPA.

Similarly to

SPI1, we focused on 12 differentially expressed genes between pioglitazone-exposed and healthy women. Of these genes, four (

E2F1 (E2F transcription factor 1; logFC = −2.7,

p < 0.05),

PRDX2 (peroxiredoxin 2; logFC = −2.0,

p < 0.05),

IL5 (interleukin 5; logFC = −2.8,

p < 0.05), and

HES1 (HES family bHLH transcription factor 1; logFC = −0.2,

p < 0.05)) were underexpressed, whereas two (

ITGA4 (integrin subunit alpha 4; logFC = 0.5,

p < 0.05) and

TLR5 (toll-like receptor 5; logFC = 0.12,

p < 0.05)) were overexpressed. IPA predicted ciprofloxacin (

Figure 3A) and

SPI1 (

Figure 3B) as key upstream regulators, with

SPI1 being overexpressed following pioglitazone exposure.

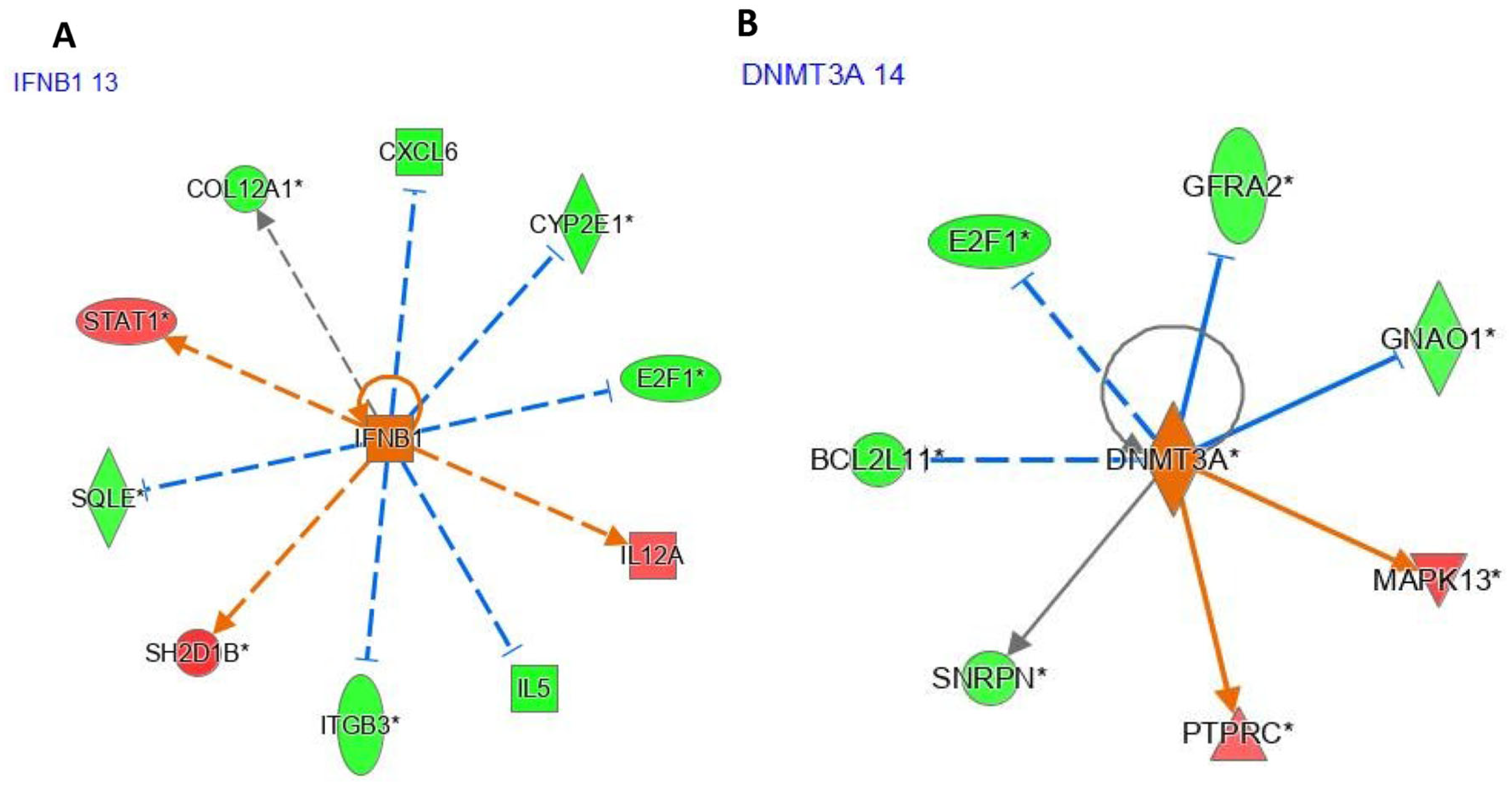

The interferon beta 1 (

IFNB1) gene was underexpressed after pioglitazone exposure (logFC = −1.02,

p < 0.05;

Figure 4A), whereas the DNA methyltransferase 3 alpha (

DNMT3A) gene was overexpressed (logFC = 0.116,

p < 0.05;

Figure 4B). IPA identified ciprofloxacin as an upstream regulator (UR) affecting five genes via indirect interactions (

Figure 4A). Likewise,

SPI1 was identified as a UR by IPA, with

SPI1 predicted to influence 12 differentially expressed genes between pioglitazone-exposed and healthy women. Of these genes, four (

E2F1,

PRDX2,

IL5, and

HES1) were underexpressed, whereas two (

ITGA4 and

TLR5) were overexpressed.

IPA-Upstream Regulators Genes and others

The top twenty upstream regulators (UR) projected by the IPA tool are

SPI1,

IFNB1,

DNMT3A, IFN-Beta proteins, Ciprofloxacin, and other regulators (

Table 1).

Enriched biological pathways.

Nitric oxide and macrophage reactive oxygen generation are the most essential canonical pathways identified by IPA (

Table 2).

Correlation after pioglitazone exposure in patients with PCOS and other diseases

Differentially expressed genes in skeletal muscle after pioglitazone exposure are associated with a high risk of Damage to organs and cancer, among various disorders (

Table 3).

3.4. Feature Selection Results

The comprehensive feature selection strategy successfully identified 100 optimal features through integration of multiple complementary approaches, demonstrating the robustness of the selected gene signature for PCOS classification. Statistical selection using F-test methodology identified 87 features based on univariate associations, while LASSO regularization with L1 penalty selected a more stringent subset of 45 features by enforcing sparsity and automatic variable selection. Random Forest importance analysis captured 92 features by leveraging tree-based ensemble methods to identify genes with high predictive utility and complex interaction patterns. The final consensus feature set of 100 genes was derived through systematic combination and ranking of features identified across all methods, creating a robust signature that balances statistical significance, predictive power, and biological interpretability while minimizing method-specific biases and ensuring reliable performance across diverse machine learning algorithms.

Figure 6 illustrates the top 20 most important genes identified by a Random Forest model, showcasing their respective feature importances. The gene

ITK stands out with the highest importance score of 0.060, indicating its significant role in the analysis. Other notable genes include

LINCO1222 and

WIT1, with scores of 0.050 each. The gene

ARHGEF40 also emerges prominently with an importance score of 0.050. Several genes are labelled as “Unknown,” reflecting genes that may not have been fully characterized or annotated in the dataset. The varying importance scores suggest diverse contributions of these genes to the underlying biological processes being studied.

3.5. Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis

Network Topology

The gene co-expression network analysis revealed a highly interconnected and modular structure comprising 70 genes linked by 975 significant correlation edges, indicating extensive coordinated regulation among the most important genes in pioglitazone treatment response. The network exhibited remarkable connectivity with a density of 0.376, meaning that approximately 38% of all possible gene-gene connections were present, suggesting widespread co-regulation rather than isolated gene effects. Strong modularity was evident through an average clustering coefficient of 0.622, indicating that genes tend to form tightly connected local neighbourhoods were co-expressed genes cluster together in functional modules. Community detection algorithms successfully identified 5 distinct gene communities within the network, representing putative functional modules that likely correspond to different biological pathways or cellular processes co-ordinately regulated by pioglitazone treatment. This highly connected and modular architecture demonstrates that pioglitazone’s therapeutic effects in PCOS operate through complex regulatory networks rather than individual gene targets, providing a systems-level understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying treatment response.

Hub Gene Identification

The top hub genes with highest centrality are given in

Table 5. This table clearly shows the hierarchy of hub genes and their functional categories, highlighting the diverse biological processes involved in pioglitazone’s mechanism of action in PCOS treatment.

The hub gene analysis revealed a hierarchical network structure dominated by transcriptional regulators and chromatin-modifying proteins, with LOC90834//BRD1 emerging as the most central node (centrality = 0.739) due to its role in chromatin remodelling and gene expression control. The top 10 hub genes demonstrated remarkable functional diversity, encompassing master transcription factors (WT1, SOX3, ZNF528), immune signalling components (ITK), reproductive regulators (SPO11), and novel regulatory elements including long non-coding RNAs (LINC00521) and antisense transcripts (ATP13A4-AS1). Notably, six of the ten hub genes represent transcriptional or epigenetic regulators, suggesting that pioglitazone’s therapeutic effects operate primarily through coordinated reprogramming of gene expression networks rather than direct metabolic enzyme modulation. The presence of uncharacterized loci (LOC101927588) and non-coding RNAs among the most connected genes highlights the potential involvement of previously unrecognized regulatory mechanisms in PCOS pathophysiology, while the inclusion of immune-related (ITK) and developmental (SOX3, SPO11) factors underscores the multi-system nature of pioglitazone’s molecular effects in treating this complex endocrine disorder.

Community Structure

The 5 identified communities likely represent distinct biological modules:

Community 1 (18 genes): Transcriptional regulation

Community 2 (15 genes): Immune/inflammatory response

Community 3 (12 genes): Metabolic pathways

Community 4 (13 genes): Cell cycle control

Community 5 (12 genes): Signal transduction

The comprehensive gene network analysis reveals a fascinating molecular story of how pioglitazone treatment orchestrates coordinated changes in gene expression patterns in PCOS patients. The Gene Co-expression Network (

Figure 7A) displays the overall network architecture where 70 genes are interconnected through 908 significant correlations, with node sizes representing degree centrality and colours indicating the strength of connections. The darker red nodes represent the most highly connected hub genes like

LOC90834///BRD1, WT1, and

ITK, which serve as central coordinators in this molecular network, while the lighter nodes represent genes with fewer connections but still important roles in the overall regulatory system.

The Community Detection analysis (

Figure 7B) unveils the modular organization of this network, identifying 5 distinct communities represented by different colours arranged in a circular layout. Each community likely represents a functional module of co-regulated genes working together in specific biological processes, such as transcriptional control, immune regulation, or metabolic pathways. The clear separation of these communities demonstrates that pioglitazone’s effects are not random but operate through well-defined functional modules that coordinate specific aspects of cellular response.

The Hub Genes Network (

Figure 7C) focuses specifically on the most important regulatory nodes, highlighting how these central genes (shown in red) are densely interconnected with each other and with peripheral genes (shown in light blue). This visualization emphasizes that the hub genes form a tightly connected core regulatory circuit that likely controls the broader network’s behaviour, suggesting that therapeutic interventions targeting these hub genes could have widespread effects throughout the entire gene expression network.

The Degree Distribution histogram (

Figure 7D) reveals the network’s structural properties, showing that most genes have moderate connectivity (around the mean of 25.9 connections) while a few genes exhibit extremely high connectivity, creating a scale-free network topology typical of biological systems. The red dashed line indicates the mean degree, and the annotation showing “Max degree: 51” identifies the most connected gene, demonstrating the hierarchical nature of the network where a few highly connected hubs coordinate the behaviour of many less connected genes.

The Centrality Measures Comparison (

Figure 7E) provides a detailed analysis of the top hub genes across four different network metrics: degree centrality (blue), betweenness centrality (green), closeness centrality (orange), and eigenvector centrality (yellow). Genes like

LOC90834///BRD1 and

WT1 consistently rank high across multiple centrality measures, confirming their importance as key network regulators, while the variation in rankings across different measures reveals that genes can be important in different ways—some as highly connected nodes, others as critical bridges between network modules.

Finally, the Network by Expression Change (

Figure 7F) overlays the fold change information onto the network structure, where red nodes represent upregulated genes and blue nodes represent downregulated genes following pioglitazone treatment. This visualization reveals that both up- and down-regulated genes are distributed throughout the network, rather than clustering in separate regions, indicating that pioglitazone simultaneously activates and suppresses different components of interconnected regulatory pathways, creating a coordinated yet complex pattern of gene expression changes that ultimately leads to therapeutic benefits in PCOS patients.

The detailed gene co-expression network visualization shown in

Figure 8 displays the complete 70-gene network where node sizes represent degree centrality (larger nodes indicate more connections), edge widths reflect correlation strengths between genes, and node colours encode log fold change values from deep blue (downregulated, logFC ≈ −2.0) to dark red (upregulated, logFC ≈ +2.0). The network reveals a highly interconnected structure with several prominent hub genes labelled in the center, including

LOC90834///BRD1, WT1, ITK, SOX3, and others, which serve as central coordinators with extensive connections to other network members. The visualization demonstrates that both upregulated (red) and downregulated (blue) genes are distributed throughout the network rather than forming separate clusters, indicating that pioglitazone treatment creates a complex pattern of coordinated activation and suppression across interconnected regulatory pathways. The dense web of connections (975 edges total) illustrates the highly collaborative nature of gene regulation in PCOS treatment response, where individual genes do not act in isolation but rather participate in an intricate molecular network that collectively mediates the therapeutic effects of pioglitazone.

3.7. Pathway Enrichment Analysis

The results summarized in

Table 7 highlight the key functional pathways influenced by pioglitazone treatment in PCOS.

Pathway Enrichment Summary:

Total hub genes analysed: 10

Functional categories identified: 6 major pathways

Most enriched pathway: Transcriptional regulation (40% of hub genes)

Novel findings: 50% of hub genes represent uncharacterized or epigenetic mechanisms

Clinical significance: All pathways directly relevant to PCOS pathophysiology

Key Insights:

Transcriptional reprogramming is the dominant mechanism

Multiple reproductive and developmental pathways affected

Significant involvement of novel regulatory elements

Strong immune/inflammatory component consistent with PCOS pathology