Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Tibetan Medicinal Plant Soroseris hookeriana

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection, DNA Extraction, and Sequencing

2.2. Genome Assembly and Annotation

2.3. Analysis of Codon Usage Bias

2.4. Repeat Sequence Analysis

2.5. Comparative Genomic Analysis

2.6. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

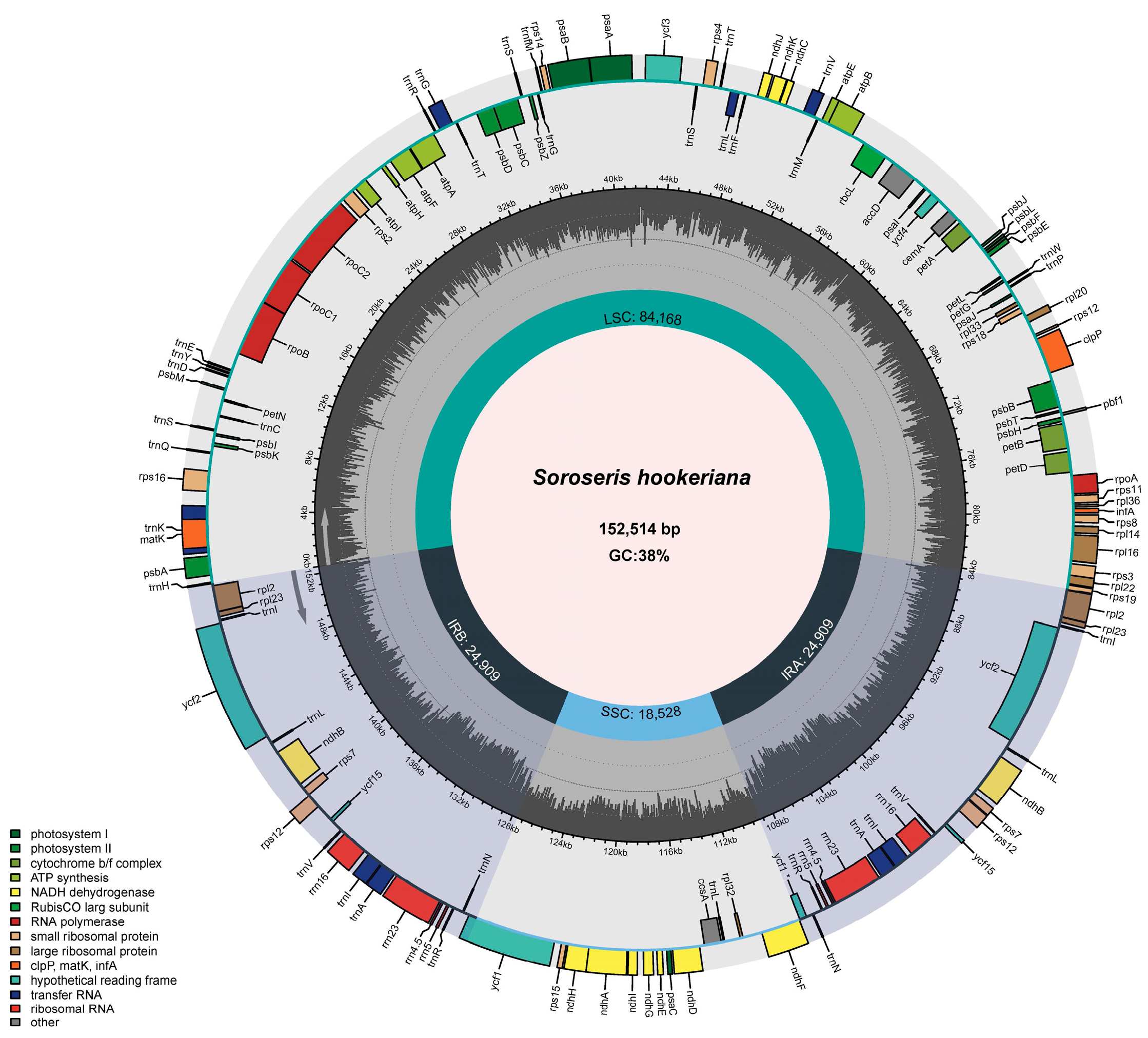

3.1. Characteristics of S. hookeriana cpDNA

3.2. Codon Usage Bias

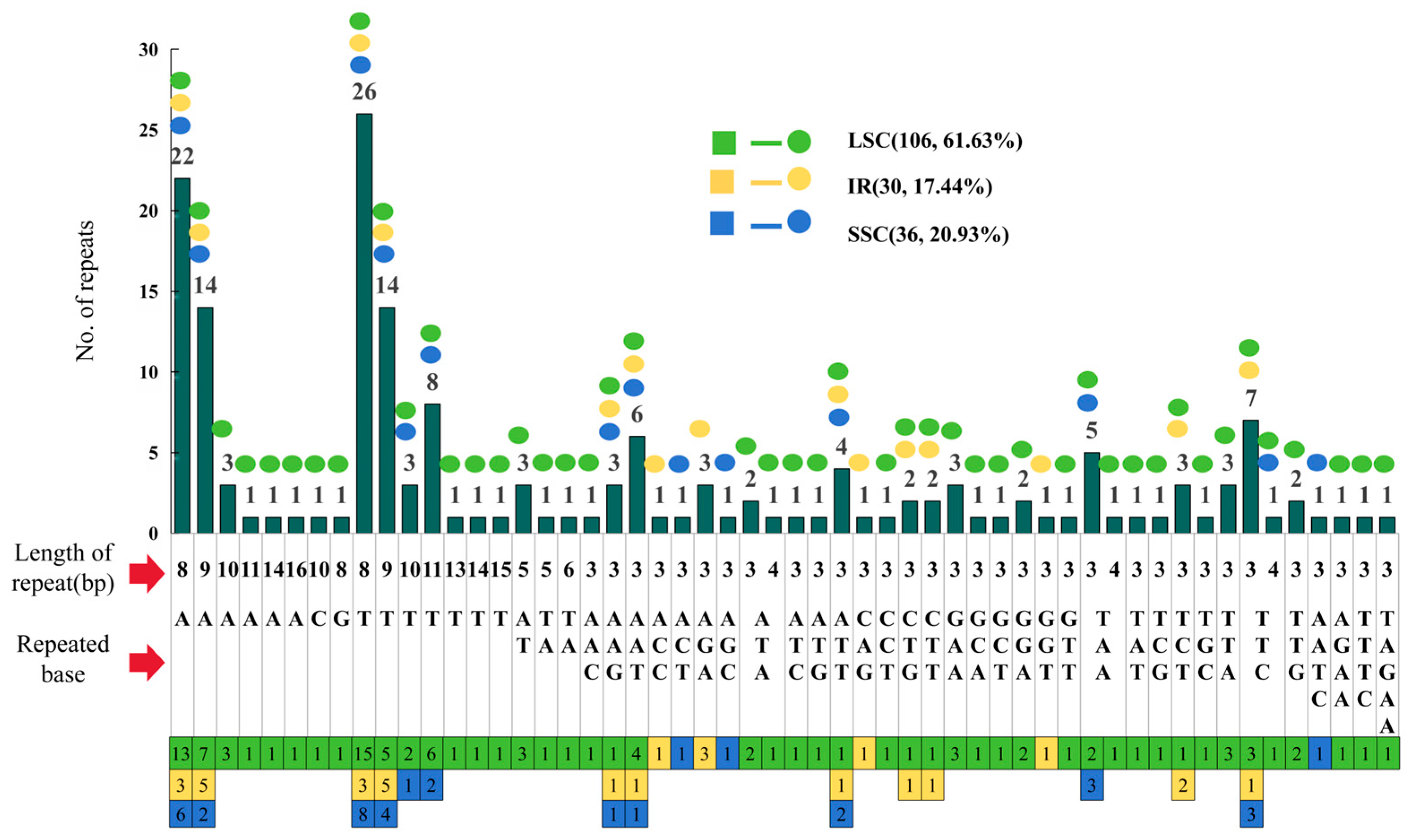

3.3. Repeat Sequence

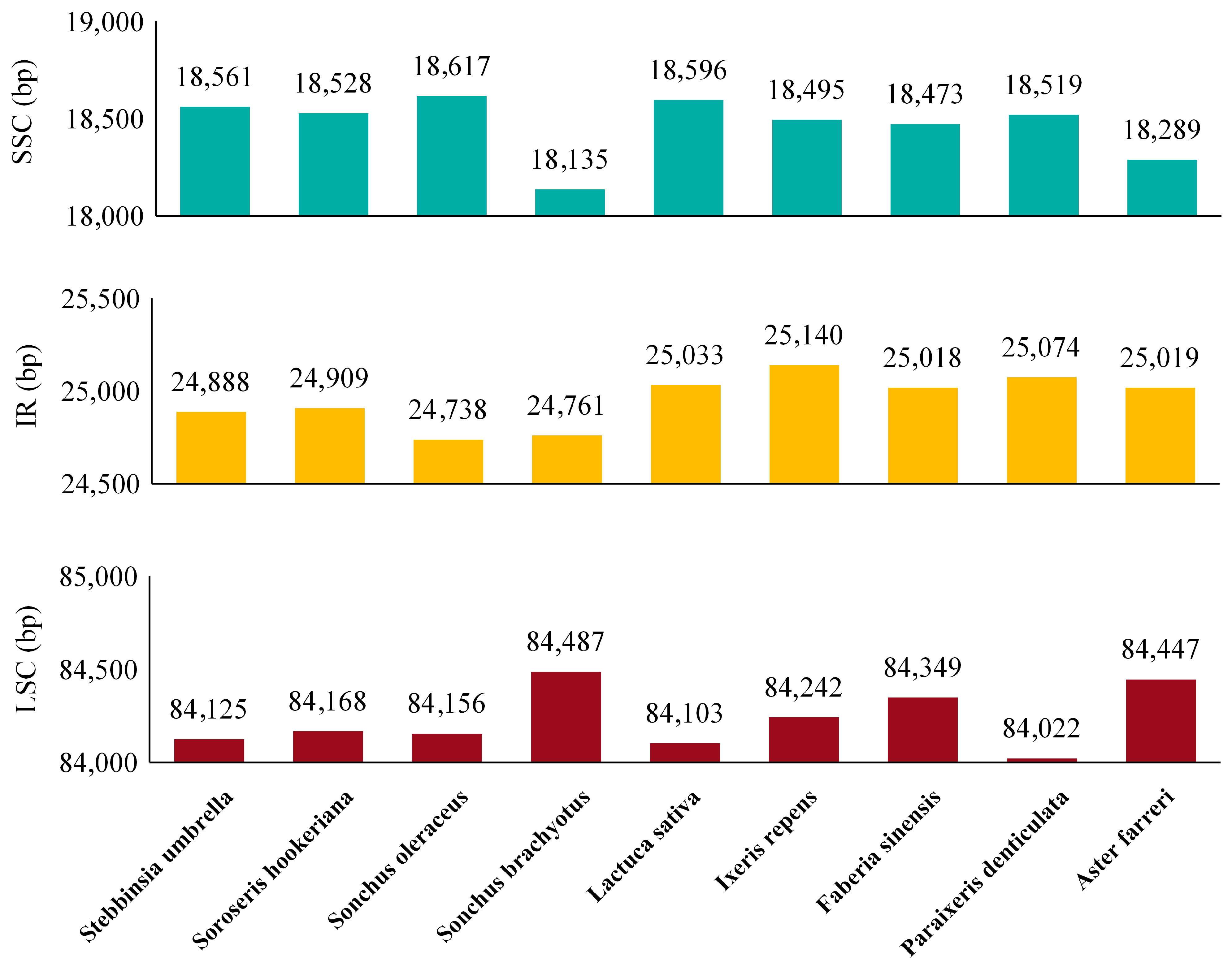

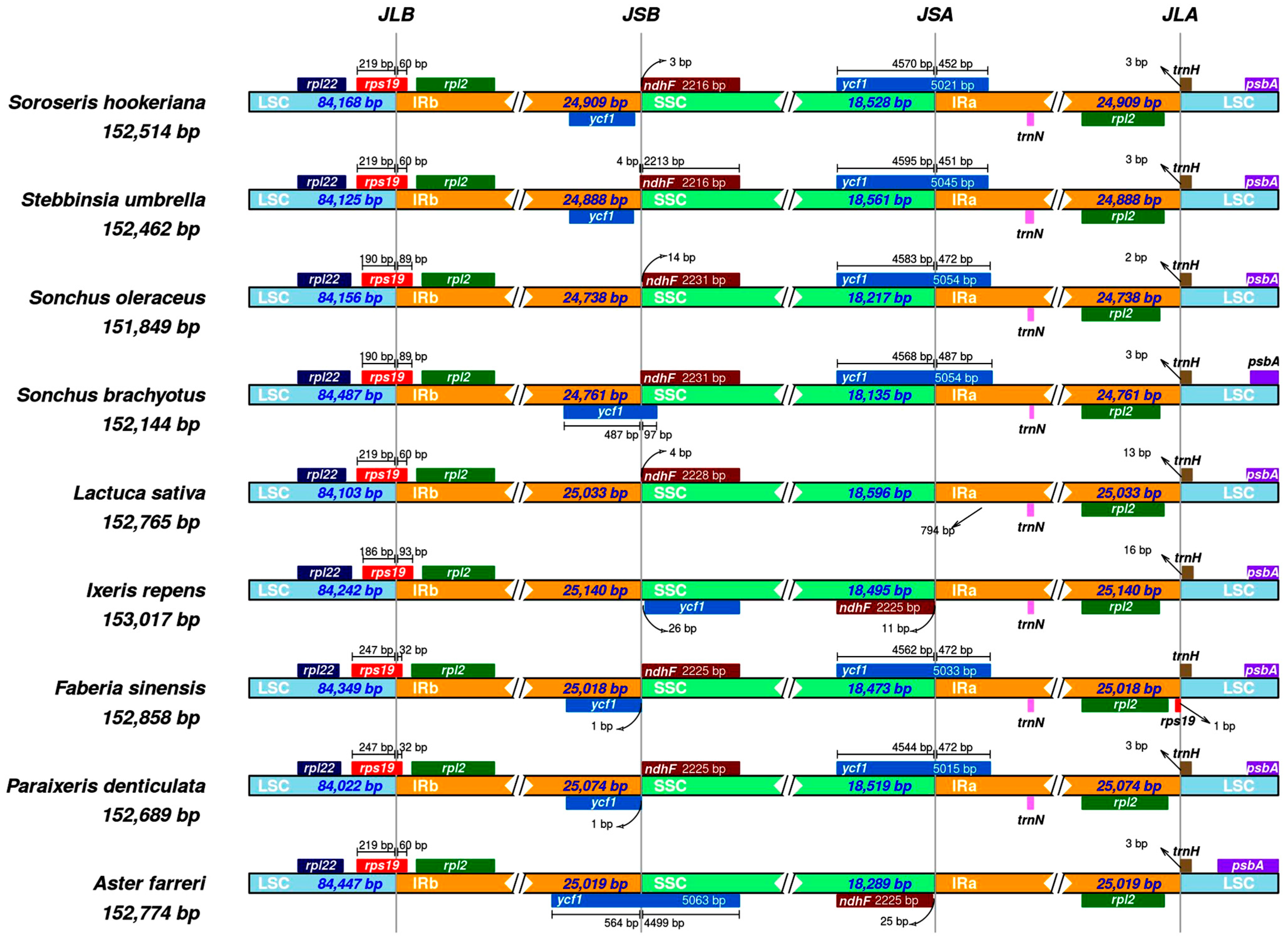

3.4. Comparative cp Genome Analysis and IR Boundary Analysis

3.5. Phylogenetic Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stebbins, G.L. Studies in the Cichorieae: Dubyaea and Soroseris, endemics of the Sino-Himalayan region. Mem. Torrey Bot. Club. 1940, 19, 1–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J.Y. New Advances in Research of Chemical Contituents and Pharmacological Action of Genus Soroseris. J. Liaoning Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2011, 13, 212–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.C.; Zhu, Q.X.; Tan, R.X. New antimicrobial mono-and sesquiterpenes from Soroseris hookeriana subsp. erysimoides. Planta Med. 2000, 66, 541–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, G.I. Chloroplast origin and integration. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susann, W.; Gerald, M.S.; Claude, W.P.; Kai, F.M.; Dietmar, Q. The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: Gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol. Biol. 2011, 76, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.T.; Zhang, L.C.; Chen, W.S.; Li, Q. Analysis of Chloroplast Genomes in 1342 Plants. Genom. Appl. Biol. 2017, 36, 4323–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catherine, J.N.; Craig, M.H.; Juan, D.M.; Ainnatul, A.A.; Satomi, H.; Julia, P.; David, E.; Jacqueline, B. Wild Origins of Macadamia Domestication Identified Through Intraspecific Chloroplast Genome Sequencing. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twydord, A.D.; Ness, R.W. Strategies for complete plastid genome sequencing. Mol. Ecol. Res. 2017, 17, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Cao, Q.; Yu, K.; Wang, Z.; Chen, S.; Chen, F.; Song, A. Chloroplast phylogenomics reveals the maternal ancestry of cultivated chrysanthemums. Genom. Commun. 2025, 2, e019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, J.; Nie, L.; Wang, M.; Tiwari, R.; Tembrock, L.R.; Wang, J. The Mendelian pea pan-plastome: Insights into genomic structure, evolutionary history, and genetic diversity of an essential food crop. Genom. Commun. 2024, 1, e004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Qian, J.; Sun, Z.Y.; Xu, X.L.; Chen, S.L. Complete chloroplast genome of medicinal plant Lonicera japonica: Genome rearrangement, intron gain and loss, and implications for phylogenetic studies. Molecules 2017, 22, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, R.K.; Cai, Z.Q.; Raubeson, L.A.; Daniell, H.; de Pamphilis, C.W.; Leebeans-Mack, J.; Müller, K.F.; Guisinger-Bellian, M.; Haberle, R.C.; Hansen, A.K.; et al. Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19369–19374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heng, L.M.; Zheng, Y.L.; Zhao, Y.B.; Wang, Y.J. Radiation of members of the Soroserishookeriana complex (Asteraceae) on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau and their proposed taxonomic treatment. PhytoKeys 2018, 114, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M. Study on Diversity and Utilization of Medicine Plant Resources in Yushu City. Master’s Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, J.J.; Becklund, L.E.; Carey, S.J.; Fabre, P.P. What is the “modified” CTAB protocol? Characterizing modifications to the CTAB DNA extraction protocol. Appl. Plant Sci. 2023, 11, e11517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.J.; Yu, W.B.; Yang, J.B.; Song, Y.; DePamphilis, C.W.; Yi, T.S.; Li, D.Z. GetOrganelle: A fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Chen, H.; Jiang, M.; Wang, L.; Wu, X.; Huang, L.; Liu, C. CPGAVAS2, an integrated plastome sequence annotator and analyzer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W65–W73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ni, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Chen, H.; Liu, C. CPGView: A package for visualizing detailed chloroplast genome structures. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2023, 23, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Poczai, P.; Hyvönen, J.; Tang, J.; Amiryousefi, A. Chloroplot: An online program for the versatile plotting of organelle genomes. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 576124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quax, T.E.; Claassens, N.J.; Söll, D.; van der Oost, J. Codon Bias as a Means to Fine-Tune Gene Expression. Mol. Cell. 2015, 59, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, E.E.; Lotzer, J.; Eberle, M. Codon usage in plant genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989, 17, 477–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebert, D.; Peakall, R.O.D. Chloroplast simple sequence repeats (cpSSRs): Technical resources and recommendations for expanding cpSSR discovery and applications to a wide array of plant species. Mol. Ecol. Res. 2009, 9, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, C.; Brudno, M.; Schwartz, J.R.; Poliakov, A.; Rubin, E.M.; Frazer, K.A.; Pachter, L.S.; Dubchak, I. VISTA: Visualizing global DNA sequence alignments of arbitrary length. Bioinformatics 2000, 16, 1046–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, K.A.; Pachter, L.; Poliakov, A.; Rubin, E.M.; Dubchak, I. VISTA: Computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiryousefi, A.; Hyvönen, J.; Poczai, P. IRscope: An online program to visualize the junction sites of chloroplast genomes. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3030–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Schmidt, H.A.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naver, H.; Boudreau, E.; Rochaix, J.D. Functional studies of Ycf3: Its role in assembly of photosystem I and interactions with some of its subunits. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 2731–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, E.; Takahashi, Y.; Lemieux, C.; Turmel, M.; Rochaix, J.D. The chloroplast ycf3 and ycf4 open reading frames of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii are required for the accumulation of the photosystem I complex. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 6095–6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.H.; Song, X.Q.; Zheng, J.W.; Cao, M.; Zhang, Z.H.; Tang, Z.H. Effects of moderate ultraviolet radiation enhancement on photosynthetic characteristics and medicinal active components of Dictamnus dasycarpus. Guihaia 2022, 42, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Irimia, M.; Roy, S.W. Spliceosomal introns as tools for genomic and evolutionary analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 1703–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhu, L.; Kumar, K.; Kumar, S.; Dass, A.; Pathak, R.; Bhardwaj, A.; Pandey, P.; Cuu, N.V.; Rawat, B.S.; Reddy, V.S. Chloroplasts evolved an additional layer of translational regulation based on non-AUG start codons for proteins with different turnover rates. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provan, J. Novel chloroplast microsatellites reveal cytoplasmic variation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Ecol. 2000, 9, 2183–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, M.L.; Mitchell, F.J.; Coyne, S.; Kavanagh, T.A.; Burke, J.I.; Salamin, N.; Dowding, P.; Hodkinson, T.R. Plastid genome characterisation in Brassica and Brassicaceae using a new set of nine SSRs. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006, 113, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Guo, L.L.; Zhao, W.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Shen, X.F.; Wu, M.L.; Hou, X.G. Complete chloroplast genome sequence and phylogenetic analysis of Paeonia ostii. Molecules 2018, 23, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raubeson, L.A.; Peery, R.; Chumley, T.W.; Dziubek, C.; Fourcade, H.M.; Boorem, J.L.; Jansen, R.K. Comparative chloroplast genomics: Analyses including new sequences from the angiosperms Nuphar advena and Ranunculus macranthus. BMC Genom. 2007, 8, 174–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.J.; Cheng, C.L.; Chang, C.C.; Wu, C.L.; Su, T.M.; Chaw, S.M. Dynamics and evolution of the inverted repeat-large single copy junctions in the chloroplast genomes of monocots. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008, 8, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drescher, A.; Ruf, S.; Calsa, T. The two largest chloroplast genome-encoded open reading frames of higher plants are essential genes. Plant J. 2010, 22, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, C.F.; Goldbecker, E.S.; Vries, J.D. Functional genomic perspectives on plant terrestrialization. Trends Genet. 2025, 41, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbecker, E.S.; Vries, J.D. Systems biology of streptophyte cell evolution. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2025, 76, 493–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.R. The Morphological and Systematic Studies of the Subfamily Cichorioideae Taxa in China (Asteraceae). Ph.D. Thesis, Harbin Normal University, Harbin, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nucleotide Statistics | Percentage of Bases | Length (bp) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (%) | C (%) | G (%) | T (%) | GC (%) | ||

| Whole cp genome | 31.08 | 18.78 | 18.94 | 31.19 | 37.73 | 152,514 |

| LSC | 31.86 | 17.68 | 18.26 | 32.20 | 35.94 | 84,168 |

| SSC | 34.67 | 16.34 | 15.00 | 33.99 | 31.34 | 18,528 |

| IRA | 28.62 | 22.33 | 20.80 | 28.25 | 43.12 | 24,909 |

| IRB | 28.25 | 20.80 | 22.33 | 28.62 | 43.12 | 24,909 |

| Category | Gene Group | Gene Name |

|---|---|---|

| Photosynthesis | Subunits of photosystem I | psaA,psaB,psaC,psaI,psaJ |

| Subunits of photosystem II | psbA,psbB,psbC,psbD,psbE,psbF,psbH,psbI,psbJ,psbK,psbL,psbM,psbT,psbZ | |

| Subunits of NADH dehydrogenase | ndhA *,ndhB * (2),ndhC,ndhD,ndhE,ndhF, ndhG,ndhH,ndhI,ndhJ,ndhK | |

| Subunits of cytochrome b/f complex | petA,petB *,petD *,petG,petL,petN | |

| Subunits of ATP synthase | atpA,atpB,atpE,atpF *,atpH,atpI | |

| Large subunit of rubisco | rbcL | |

| Self-replication | Proteins of large ribosomal subunit | rpl14,rpl16 *,rpl2 * (2),rpl20,rpl22,rpl23(2), rpl32,rpl33,rpl36 |

| Proteins of small ribosomal subunit | rps11,rps12 ** (2),rps14,rps15,rps16 *,rps18,rps19,rps2,rps3,rps4,rps7(2),rps8 | |

| Subunits of RNA polymerase | rpoA,rpoB,rpoC1 *,rpoC2 | |

| Ribosomal RNAs | rrn16(2),rrn23(2),rrn4.5(2),rrn5(2) | |

| Transfer RNAs | trnA-UGC * (2),trnC-GCA,trnD-GUC,trnE-UUC,trnF-GAA,trnG-GCC,trnG-UCC *,trnH-GUG,trnI-CAU(2),trnI-GAU * (2),trnK-UUU *,trnL-CAA(2),trnL-UAA *,trnL-UAG,trnM-CAU,trnN-GUU(2),trnP-UGG,trnQ-UUG,trnR-ACG(2),trnR-UCU,trnS-GCU,trnS-GGA,trnS-UGA,trnT-GGU,trnT-UGU,trnV-GAC(2),trnV-UAC*,trnW-CCA,trnY-GUA,trnfM-CAU | |

| Other genes | Maturase | matK |

| Protease | clpP ** | |

| Envelope membrane protein | cemA | |

| Acetyl-CoA carboxylase | accD | |

| c-type cytochrome synthesis gene | ccsA | |

| Translation initiation factor | infA | |

| other | pbf1 | |

| Genes of unknown function | Conserved hypothetical chloroplast ORF | # ycf1,ycf1,ycf15(2),ycf2(2),ycf3 **,ycf4 |

| Gene | Location | Exon I (bp) | Intron II (bp) | Exon II (bp) | Intron II (bp) | Exon III (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| trnK-UUU | LSC | 37 | 2536 | 35 | ||

| rps16 | LSC | 40 | 856 | 227 | ||

| rpoC1 | LSC | 432 | 724 | 1641 | ||

| atpF | LSC | 144 | 707 | 411 | ||

| trnG-UCC | LSC | 23 | 712 | 47 | ||

| ycf3 | LSC | 124 | 738 | 230 | 699 | 153 |

| trnL-UAA | LSC | 35 | 396 | 50 | ||

| trnV-UAC | LSC | 38 | 575 | 35 | ||

| rps12 | IRa | 114 | - | 232 | 537 | 26 |

| clpP | LSC | 71 | 625 | 292 | 814 | 228 |

| petB | LSC | 6 | 770 | 642 | ||

| petD | LSC | 8 | 700 | 475 | ||

| rpl16 | LSC | 9 | 1053 | 399 | ||

| rpl2 | IRb | 390 | 665 | 435 | ||

| ndhB | IRb | 777 | 669 | 756 | ||

| rps12 | IRb | 232 | - | 26 | 537 | 114 |

| trnI-GAU | IRb | 38 | 779 | 35 | ||

| trnA-UGC | IRb | 38 | 821 | 35 | ||

| ndhA | SSC | 553 | 1055 | 539 | ||

| trnA-UGC | IRa | 38 | 821 | 35 | ||

| trnI-GAU | IRa | 38 | 779 | 35 | ||

| ndhB | IRa | 777 | 669 | 756 | ||

| rpl2 | IRa | 390 | 665 | 435 |

| Amino Acid | Codon | No. | RSCU | tRNA | Amino Acid | Codon | No. | RSCU | tRNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ala | GCA | 419 | 1.1736 | trnA-UGC | Asn | AAC | 283 | 0.4412 | |

| Ala | GCC | 224 | 0.6276 | trnA-UGC | Asn | AAU | 1000 | 1.5588 | |

| Ala | GCG | 159 | 0.4452 | trnA-UGC | Pro | CCA | 333 | 1.2012 | |

| Ala | GCU | 626 | 1.7536 | Pro | CCC | 199 | 0.7176 | ||

| Cys | UGC | 78 | 0.5436 | Pro | CCG | 161 | 0.5808 | ||

| Cys | UGU | 209 | 1.4564 | Pro | CCU | 416 | 1.5004 | ||

| Asp | GAC | 214 | 0.4068 | Gln | CAA | 720 | 1.5238 | ||

| Asp | GAU | 838 | 1.5932 | Gln | CAG | 225 | 0.4762 | ||

| Glu | GAA | 987 | 1.4732 | Arg | AGA | 490 | 1.8396 | ||

| Glu | GAG | 353 | 0.5268 | Arg | AGG | 185 | 0.6948 | ||

| Phe | UUC | 530 | 0.711 | Arg | CGA | 338 | 1.269 | ||

| Phe | UUU | 961 | 1.289 | Arg | CGC | 105 | 0.3942 | ||

| Gly | GGA | 685 | 1.5352 | trnG-UCC | Arg | CGG | 126 | 0.4728 | |

| Gly | GGC | 203 | 0.4548 | Arg | CGU | 354 | 1.329 | ||

| Gly | GGG | 315 | 0.706 | Ser | AGC | 115 | 0.3402 | ||

| Gly | GGU | 582 | 1.3044 | Ser | AGU | 408 | 1.2078 | ||

| His | CAC | 151 | 0.4856 | Ser | UCA | 410 | 1.2138 | ||

| His | CAU | 471 | 1.5144 | Ser | UCC | 318 | 0.9414 | ||

| Ile | AUA | 690 | 0.9387 | Ser | UCG | 179 | 0.5298 | ||

| Ile | AUC | 449 | 0.6108 | trnI-GAU | Ser | UCU | 597 | 1.767 | |

| Ile | AUU | 1066 | 1.4502 | trnI-GAU | Thr | ACA | 409 | 1.25 | |

| Lys | AAA | 1027 | 1.4682 | Thr | ACC | 245 | 0.7488 | ||

| Lys | AAG | 372 | 0.5318 | Thr | ACG | 134 | 0.4096 | ||

| Leu | CUA | 385 | 0.8214 | Thr | ACU | 521 | 1.592 | ||

| Leu | CUC | 190 | 0.4056 | Val | GUA | 523 | 1.4912 | trnV-UAC | |

| Leu | CUG | 185 | 0.3948 | Val | GUC | 183 | 0.5216 | trnV-UAC | |

| Leu | CUU | 615 | 1.3122 | Val | GUG | 192 | 0.5472 | trnV-UAC | |

| Leu | UUA | 851 | 1.8156 | trnL-UAA | Val | GUU | 505 | 1.4396 | |

| Leu | UUG | 586 | 1.2504 | trnL-UAA | Trp | UGG | 453 | 1 | |

| Met | AUG | 627 | 1.9936 | Tyr | UAC | 189 | 0.3826 | ||

| Met | GUG | 2 | 0.0064 | Tyr | UAU | 799 | 1.6174 |

| ID | Repeat I Start | Type | Size (bp) | Repeat II Start | Mismatch (bp) | E-Value | Gene | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 84,169 | P | 24,909 | 127,606 | 0 | 0 | - | IR |

| 2 | 91,414 | F | 60 | 91,432 | 0 | 4.92 × 10−27 | ycf2;ycf2 | IRb;IRb |

| 3 | 91,414 | P | 60 | 145,192 | 0 | 4.92 × 10−27 | ycf2;ycf2 | IRb;IRa |

| 4 | 91,432 | P | 60 | 145,210 | 0 | 4.92 × 10−27 | ycf2;ycf2 | IRb;IRa |

| 5 | 145,192 | F | 60 | 145,210 | 0 | 4.92 × 10−27 | ycf2;ycf2 | IRa;IRa |

| 6 | 56,535 | F | 50 | 56,560 | −1 | 7.74 × 10−19 | rbcL;rbcL | LSC;LSC |

| 7 | 111,541 | P | 49 | 111,541 | −1 | 3.03 × 10−18 | IGS | SSC;SSC |

| 8 | 54,778 | F | 48 | 54,794 | 0 | 8.26 × 10−20 | IGS | LSC;LSC |

| 9 | 74,262 | P | 48 | 74,262 | −2 | 8.38 × 10−16 | pbf1;pbf1 | LSC;LSC |

| 10 | 46,699 | P | 46 | 46,699 | 0 | 1.32 × 10−18 | IGS | LSC;LSC |

| 11 | 10,707 | P | 42 | 10,707 | 0 | 3.38 × 10−16 | IGS | LSC;LSC |

| 12 | 91,414 | F | 42 | 91,450 | 0 | 3.38 × 10−16 | ycf2;ycf2 | IRb;IRb |

| 13 | 145,192 | F | 42 | 145,228 | 0 | 3.38 × 10−16 | ycf2;ycf2 | IRa;IRa |

| 14 | 30,102 | F | 41 | 30,115 | 0 | 1.35 × 10−15 | IGS | LSC;LSC |

| 15 | 43,376 | F | 41 | 98,203 | −2 | 9.98 × 10−12 | ycf3;IGS | LSC;IRb |

| 16 | 43,376 | P | 41 | 138,440 | −2 | 9.98 × 10−12 | ycf3;IGS | LSC;IRa |

| 17 | 56,546 | F | 39 | 56,571 | 0 | 2.16 × 10−14 | rbcL;IGS | LSC;LSC |

| 18 | 43,378 | F | 39 | 119,515 | −1 | 2.53 × 10−12 | ycf3;ndhA | LSC;SSC |

| 19 | 98,205 | F | 39 | 119,515 | −1 | 2.53 × 10−12 | IGS;ndhA | IRb;SSC |

| 20 | 119,515 | P | 39 | 138,440 | −1 | 2.53 × 10−12 | ndhA;IGS | SSC;IRa |

| 21 | 38,362 | F | 36 | 40,586 | −3 | 2.67 × 10−7 | psaB;psaA | LSC;LSC |

| 22 | 95,161 | F | 35 | 119,518 | −3 | 9.79 × 10−7 | ndhB;ndhA | IRb;SSC |

| 23 | 119,518 | P | 35 | 141,488 | −3 | 9.79 × 10−7 | ndhA;ndhB | SSC;IRa |

| 24 | 30,097 | F | 33 | 30,123 | −3 | 1.31 × 10−5 | IGS | LSC;LSC |

| 25 | 54,778 | F | 32 | 54,810 | 0 | 3.55 × 10−10 | IGS | LSC;LSC |

| 26 | 8531 | F | 32 | 35,184 | −3 | 4.75 × 10−5 | trnS-GCU;trnS-UGA | LSC;LSC |

| 27 | 59,274 | R | 31 | 59,277 | −2 | 5.94 × 10−6 | IGS | LSC;LSC |

| 28 | 8533 | P | 30 | 45,134 | 0 | 5.67 × 10−9 | trnS-GCU;trnS-GGA | LSC;LSC |

| 29 | 12,555 | F | 30 | 12,583 | −2 | 2.22 × 10−5 | IGS | LSC;LSC |

| 30 | 107,071 | F | 30 | 107,103 | −2 | 2.22 × 10−5 | IGS | IRb;IRb |

| 31 | 107,071 | P | 30 | 129,551 | −2 | 2.22 × 10−5 | IGS | IRb;IRa |

| 32 | 107,103 | P | 30 | 129,583 | −2 | 2.22 × 10−5 | IGS | IRb;IRa |

| 33 | 129,551 | F | 30 | 129,583 | −2 | 2.22 × 10−5 | IGS | IRa;IRa |

| 34 | 35,186 | P | 30 | 45,134 | −3 | 6.22 × 10−4 | trnS-UGA;trnS-GGA | LSC;LSC |

| 35 | 38,373 | F | 30 | 40,597 | −3 | 6.22 × 10−4 | psaB;psaA | LSC;LSC |

| 36 | 67,480 | F | 30 | 99,385 | −3 | 6.22 × 10−4 | IGS | LSC;IRb |

| 37 | 67,480 | P | 30 | 137,269 | −3 | 6.22 × 10−4 | IGS | LSC;IRa |

| 38 | 82,407 | P | 30 | 82,409 | −3 | 6.22 × 10−4 | rpl16;rpl16 | LSC;LSC |

| 39 | 31,844 | R | 30 | 31,844 | −2 | 2.22 × 10−5 | IGS | LSC;LSC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tian, T.; Lin, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J. Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Tibetan Medicinal Plant Soroseris hookeriana. Genes 2026, 17, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010024

Tian T, Lin X, Wang Y, Wang J. Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Tibetan Medicinal Plant Soroseris hookeriana. Genes. 2026; 17(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Tian, Xiuying Lin, Yiming Wang, and Jiuli Wang. 2026. "Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Tibetan Medicinal Plant Soroseris hookeriana" Genes 17, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010024

APA StyleTian, T., Lin, X., Wang, Y., & Wang, J. (2026). Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Tibetan Medicinal Plant Soroseris hookeriana. Genes, 17(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes17010024