From Polymorphisms to Phenotypes: SMAD3 rs17293632 and LTBP3 rs11545200 in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bioethics and Recruitment

2.2. Clinical Characteristics

2.3. Genotyping

2.4. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Study Cohort

3.2. Laboratory and Nutritional Parameters

3.3. Disease Activity and Treatment Characteristics

3.4. Associations of LTBP3 rs11545200

3.5. Associations of SMAD3 rs17293632

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malik, T.F.; Aurelio, D.M. Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bouhuys, M.; Lexmond, W.S.; Van Rheenen, P.F. Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022058037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghione, S.; Sarter, H.; Fumery, M.; Armengol-Debeir, L.; Savoye, G.; Ley, D.; Spyckerelle, C.; Pariente, B.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Turck, D.; et al. Dramatic Increase in Incidence of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease (1988–2011): A Population-Based Study of French Adolescents. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, R.; Kuenzig, M.E.; Benchimol, E.I. Epidemiology of Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 52, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerushalmy-Feler, A.; Brauner, C.; Cohen, S. Dual-Targeted Therapy in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Pediatr. Drugs 2023, 25, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsen, J.R.; Sullivan, K.E.; Rabizadeh, S.; Singh, N.; Snapper, S.; Elkadri, A.; Grossman, A.B. North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Position Paper on the Evaluation and Management for Patients with Very Early-onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 70, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, M.; Christensen, H.S.; Bøgsted, M.; Colombel, J.-F.; Jess, T.; Allin, K.H. The Rising Burden of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Denmark Over Two Decades: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 1547–1554.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karolewska-Bochenek, K.; Lazowska-Przeorek, I.; Albrecht, P.; Grzybowska, K.; Ryzko, J.; Szamotulska, K.; Radzikowski, A.; Landowski, P.; Krzesiek, E.; Ignys, I.; et al. Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease among Children in Poland. A Prospective, Population-Based, 2-Year Study, 2002–2004. Digestion 2009, 79, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagórowicz, E.; Walkiewicz, D.; Kucha, P.; Perwieniec, J.; Maluchnik, M.; Wieszczy, P.; Reguła, J. Nationwide Data on Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Poland between 2009 and 2020. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2022, 132, 16194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piovani, D.; Danese, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Nikolopoulos, G.K.; Lytras, T.; Bonovas, S. Environmental Risk Factors for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 647–659.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhann, F.; Vich Vila, A.; Bonder, M.J.; Fu, J.; Gevers, D.; Visschedijk, M.C.; Spekhorst, L.M.; Alberts, R.; Franke, L.; Van Dullemen, H.M.; et al. Interplay of Host Genetics and Gut Microbiota Underlying the Onset and Clinical Presentation of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gut 2018, 67, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlig, H.H.; Charbit-Henrion, F.; Kotlarz, D.; Shouval, D.S.; Schwerd, T.; Strisciuglio, C.; de Ridder, L.; van Limbergen, J.; Macchi, M.; Snapper, S.B.; et al. Clinical Genomics for the Diagnosis of Monogenic Forms of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Position Paper From the Paediatric IBD Porto Group of European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2021, 72, 456–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, D.P.B.; Kugathasan, S.; Cho, J.H. Genetics of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology 2015, 149, 1163–1176.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, D. Personalized Medicine in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 10, 662–664. [Google Scholar]

- Atreya, R.; Neurath, M.F.; Siegmund, B. Personalizing Treatment in IBD: Hype or Reality in 2020? Can We Predict Response to Anti-TNF? Front. Med. 2020, 7, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, J.K.; Glapa-Nowak, A.; Banaszkiewicz, A.; Iwańczak, B.; Kwiecień, J.; Szaflarska-Popławska, A.; Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk, U.; Osiecki, M.; Kierkuś, J.; Hołubiec, M.; et al. HLA-DQA1*05 Associates with Extensive Ulcerative Colitis at Diagnosis: An Observational Study in Children. Genes 2021, 12, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N. IBD Risk Prediction Using Multi-Ethnic Polygenic Risk Scores. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 217–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abakkouy, Y.; Cleynen, I. The Promise of Polygenic Risk Scores as a Research Tool to Analyse the Genetics Underlying IBD Phenotypes. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2021, 15, 877–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Agrawal, M.; Ng, S.C.; Jess, T. Early-Life Exposures and the Microbiome: Implications for IBD Prevention. Gut 2024, 73, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell Doherty, R.D.; Liao, H.; Satsangi, J.J.; Ternette, N. Extended Analysis Identifies Drug-Specific Association of 2 Distinct HLA Class II Haplotypes for Development of Immunogenicity to Adalimumab and Infliximab. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 784–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapata-Cobo, P.; Salvador-Martín, S.; Velasco, M.; Palomino, L.M.; Clemente, S.; Segarra, O.; Moreno-Álvarez, A.; Fernández-Lorenzo, A.; Pérez-Moneo, B.; Montraveta, M.; et al. Polymorphisms Indicating Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease or Antigenicity to Anti-TNF Drugs as Biomarkers of Response in Children. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 194, 106859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

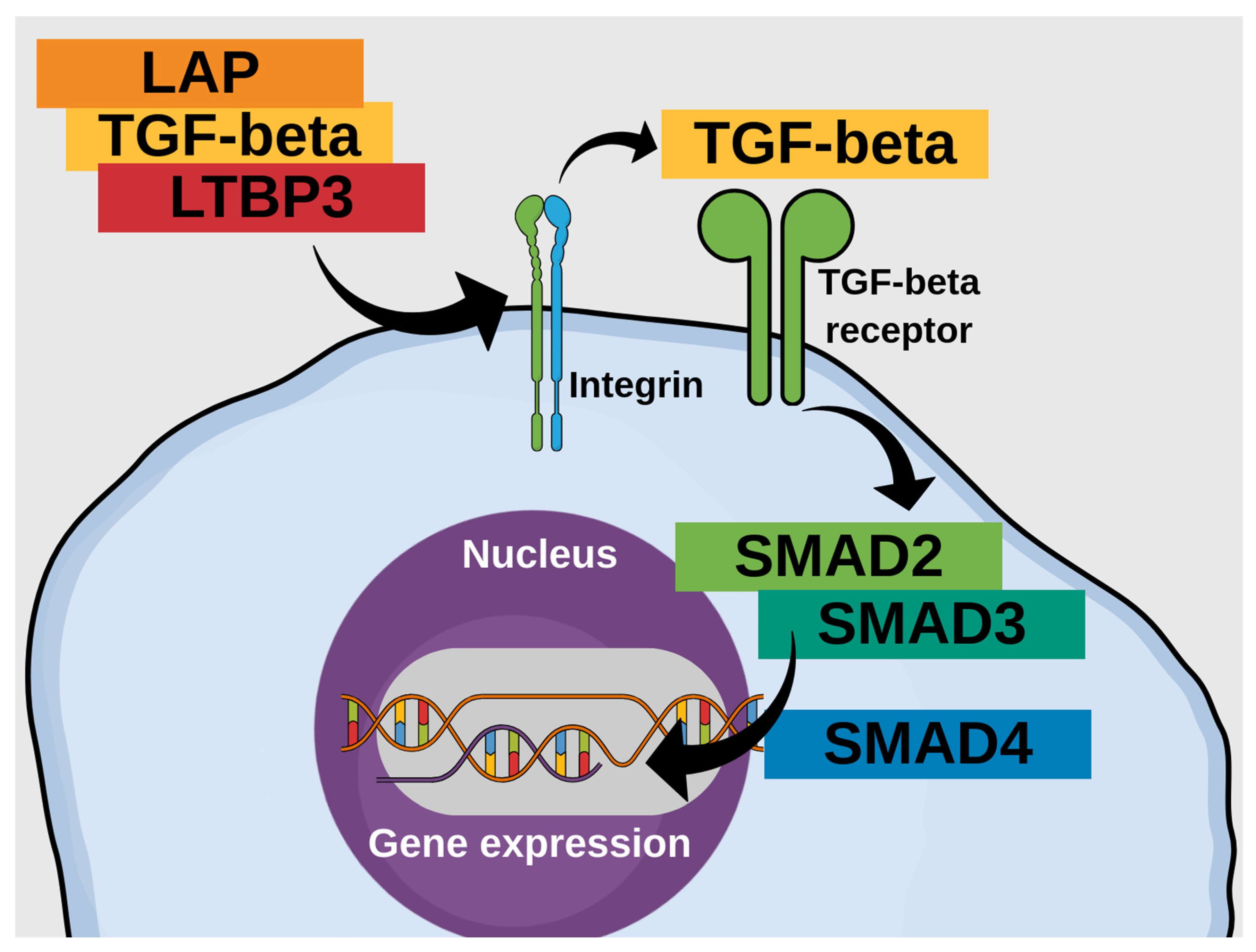

- Sedda, S.; Marafini, I.; Dinallo, V.; Di Fusco, D.; Monteleone, G. The TGF-β/Smad System in IBD Pathogenesis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 2921–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marafini, I.; Zorzi, F.; Codazza, S.; Pallone, F.; Monteleone, G. TGF-Beta Signaling Manipulation as Potential Therapy for IBD. CDT 2013, 14, 1400–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Fan, T.; Xiao, C.; Tian, H.; Zheng, Y.; Li, C.; He, J. TGF-β Signaling in Health, Disease and Therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, M.; Derynck, R.; Miyazono, K. TGF-β and the TGF-β Family: Context-Dependent Roles in Cell and Tissue Physiology. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a021873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnet-Hughes, A.; Duc, N.; Serrant, P.; Vidal, K.; Schiffrin, E.J. Bioactive Molecules in Milk and Their Role in Health and Disease: The Role of Transforming Growth Factor-Beta. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2000, 78, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, J.M.; Paintin, M.; Arnaud-Battandier, F.; Beattie, R.M.; Hollis, A.; Kitching, P.; Donnet-Hughes, A.; MacDonald, T.T.; Walker-Smith, J.A. Mucosal Healing and a Fall in Mucosal Pro-inflammatory Cytokine mRNA Induced by a Specific Oral Polymeric Diet in Paediatric Crohn’s Disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 14, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narula, N.; Dhillon, A.; Zhang, D.; Sherlock, M.E.; Tondeur, M.; Zachos, M. Enteral Nutritional Therapy for Induction of Remission in Crohn’s Disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 4, CD000542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaminath, A.; Feathers, A.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Falzon, L.; Li Ferry, S. Systematic Review with Meta-analysis: Enteral Nutrition Therapy for the Induction of Remission in Paediatric Crohn’s Disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 46, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agin, M.; Yucel, A.; Gumus, M.; Yuksekkaya, H.A.; Tumgor, G. The Effect of Enteral Nutrition Support Rich in TGF-β in the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Childhood. Medicina 2019, 55, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rheenen, P.F.; Aloi, M.; Assa, A.; Bronsky, J.; Escher, J.C.; Fagerberg, U.L.; Gasparetto, M.; Gerasimidis, K.; Griffiths, A.; Henderson, P.; et al. The Medical Management of Paediatric Crohn’s Disease: An ECCO-ESPGHAN Guideline Update. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2021, 15, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambu, R.; Warner, N.; Mulder, D.J.; Kotlarz, D.; McGovern, D.P.B.; Cho, J.; Klein, C.; Snapper, S.B.; Griffiths, A.M.; Iwama, I.; et al. A Systematic Review of Monogenic Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, e653–e663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lees, C.W.; Barrett, J.C.; Parkes, M.; Satsangi, J. New IBD Genetics: Common Pathways with Other Diseases. Gut 2011, 60, 1739–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, P.; van Limbergen, J.E.; Wilson, D.C.; Satsangi, J.; Russell, R.K. Genetics of Childhood-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.H.; Brant, S.R. Recent Insights Into the Genetics of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 1704–1712.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, S.; Borowski, K.; Espin-Garcia, O.; Milgrom, R.; Kabakchiev, B.; Stempak, J.; Panikkath, D.; Eksteen, B.; Xu, W.; Steinhart, A.H.; et al. The Unsolved Link of Genetic Markers and Crohn’s Disease Progression: A North American Cohort Experience. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25, 1541–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstockt, B.; Smith, K.G.; Lee, J.C. Genome-wide Association Studies in Crohn’s Disease: Past, Present and Future. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2018, 7, e1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.A.; Boucher, G.; Lees, C.W.; Franke, A.; D’Amato, M.; Taylor, K.D.; Lee, J.C.; Goyette, P.; Imielinski, M.; Latiano, A.; et al. Meta-Analysis Identifies 29 Additional Ulcerative Colitis Risk Loci, Increasing the Number of Confirmed Associations to 47. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.A.; Li, M.O. TGF-β: Guardian of T Cell Function. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 3973–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.W.; Martinuk, A.; Silva, A.; Lau, P.; Nikpay, M.; Eriksson, P.; Folkersen, L.; Perisic, L.; Hedin, U.; Soubeyrand, S.; et al. Functional Analysis of a Novel Genome-Wide Association Study Signal in SMAD3 That Confers Protection From Coronary Artery Disease. ATVB 2016, 36, 972–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Laar, I.M.B.H.; Oldenburg, R.A.; Pals, G.; Roos-Hesselink, J.W.; De Graaf, B.M.; Verhagen, J.M.A.; Hoedemaekers, Y.M.; Willemsen, R.; Severijnen, L.-A.; Venselaar, H.; et al. Mutations in SMAD3 Cause a Syndromic Form of Aortic Aneurysms and Dissections with Early-Onset Osteoarthritis. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morén, A.; Olofsson, A.; Stenman, G.; Sahlin, P.; Kanzaki, T.; Claesson-Welsh, L.; ten Dijke, P.; Miyazono, K.; Heldin, C.H. Identification and Characterization of LTBP-2, a Novel Latent Transforming Growth Factor-Beta-Binding Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 32469–32478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Zhao, J.; Ma, C.; Wei, J.; Wei, B.; Liu, J. Common Variants in LTBP3 Gene Contributed to the Risk of Hip Osteoarthritis in Han Chinese Population. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20192999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, A.; Koletzko, S.; Turner, D.; Escher, J.C.; Cucchiara, S.; de Ridder, L.; Kolho, K.-L.; Veres, G.; Russell, R.K.; Paerregaard, A.; et al. ESPGHAN Revised Porto Criteria for the Diagnosis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children and Adolescents. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2014, 58, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J. Study Designs in Medical Research and Their Key Characteristics. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 92, e928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicka-Gutaj, N.; Gruszczyński, D.; Guzik, P.; Mostowska, A.; Walkowiak, J. Publication Ethics of Human Studies in the Light of the Declaration of Helsinki—A Mini-Review. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 91, e700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzik, P.; Więckowska, B. Data Distribution Analysis—A Preliminary Approach to Quantitative Data in Biomedical Research. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 92, e869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, M.K.; Sykes, R.; Samples, J.; Edmunds, B.; Choi, D.; Keene, D.R.; Tufa, S.F.; Sun, Y.Y.; Keller, K.E. Identification of Missense Extracellular Matrix Gene Variants in a Large Glaucoma Pedigree and Investigation of the N700S Thrombospondin-1 Variant in Normal and Glaucomatous Trabecular Meshwork Cells. Curr. Eye Res. 2022, 47, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Letterio, J.J.; Lechleider, R.J.; Chen, L.; Hayman, R.; Gu, H.; Roberts, A.B.; Deng, C. Targeted Disruption of SMAD3 Results in Impaired Mucosal Immunity and Diminished T Cell Responsiveness to TGF-Beta. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 1280–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, C.R.; Yuan, L.; Basson, M.D. Smad3 Knockout Mice Exhibit Impaired Intestinal Mucosal Healing. Lab. Investig. 2008, 88, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, S.A.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Gardet, A.; Stevens, C.R.; Korzenik, J.R.; Sands, B.E.; Daly, M.J.; Xavier, R.J.; Yajnik, V. SMAD3 Gene Variant Is a Risk Factor for Recurrent Surgery in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. J. Crohns Colitis 2014, 8, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.P.; O’Connell, R.M.; Lennon, G.; Doherty, G.A.; Keegan, D.; O’Donoghue, D.; Mulcahy, H.; Hyland, J.; Winter, D.C.; Sheahan, K.; et al. The Influence of CTGF Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms on Outcomes in Crohn’s Disease. Ann. Surg. 2013, 258, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.D.; McGovern, D.P.B. Genetic Variation in IBD: Progress, Clues to Pathogenesis and Possible Clinical Utility. Expert. Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2016, 12, 1091–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrerio, A.L.; Frischmeyer-Guerrerio, P.A.; Huang, C.; Wu, Y.; Haritunians, T.; McGovern, D.P.B.; MacCarrick, G.L.; Brant, S.R.; Dietz, H.C. Increased Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Patients with Mutations in Genes Encoding the Receptor Subunits for TGFβ. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 2058–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Martín, S.; Raposo-Gutiérrez, I.; Navas-López, V.M.; Gallego-Fernández, C.; Moreno-Álvarez, A.; Solar-Boga, A.; Muñoz-Codoceo, R.; Magallares, L.; Martínez-Ojinaga, E.; Fobelo, M.J.; et al. Gene Signatures of Early Response to Anti-TNF Drugs in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livanos, A.E.; Dunn, A.; Fischer, J.; Ungaro, R.C.; Turpin, W.; Lee, S.-H.; Rui, S.; Del Valle, D.M.; Jougon, J.J.; Martinez-Delgado, G.; et al. Anti-Integrin Avβ6 Autoantibodies Are a Novel Biomarker That Antedate Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology 2023, 164, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worthington, J.J.; Kelly, A.; Smedley, C.; Bauché, D.; Campbell, S.; Marie, J.C.; Travis, M.A. Integrin Avβ8-Mediated TGF-β Activation by Effector Regulatory T Cells Is Essential for Suppression of T-Cell-Mediated Inflammation. Immunity 2015, 42, 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasempour, S.; Warner, N.; Guan, R.; Rodari, M.M.; Ivanochko, D.; Whittaker Hawkins, R.; Marwaha, A.; Nowak, J.K.; Liang, Y.; Mulder, D.J.; et al. Human ITGAV Variants Are Associated with Immune Dysregulation, Brain Abnormalities, and Colitis. J. Exp. Med. 2024, 221, e20240546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.; Duclaux-Loras, R.; Revenu, C.; Charbit-Henrion, F.; Begue, B.; Duroure, K.; Grimaud, L.; Guihot, A.L.; Desquiret-Dumas, V.; Zarhrate, M.; et al. Bi-Allelic Variants in IPO8 Cause a Connective Tissue Disorder Associated with Cardiovascular Defects, Skeletal Abnormalities, and Immune Dysregulation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 108, 1126–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodari, M.M.; Cerf-Bensussan, N.; Parlato, M. Dysregulation of the Immune Response in TGF-β Signalopathies. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1066375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Lin, J.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; Yu, J.; Sun, J.; Tang, N.; Jiao, C.; Ma, J.; et al. Treg and Intestinal Myofibroblasts-Derived Amphiregulin Induced by TGF-β Mediates Intestinal Fibrosis in Crohn’s Disease. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, J.K.; Adams, A.T.; Kalla, R.; Lindstrøm, J.C.; Vatn, S.; Bergemalm, D.; Keita, Å.V.; Gomollón, F.; Jahnsen, J.; Vatn, M.H.; et al. Characterisation of the Circulating Transcriptomic Landscape in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Provides Evidence for Dysregulation of Multiple Transcription Factors Including NFE2, SPI1, CEBPB, and IRF2. J. Crohns Colitis 2022, 16, 1255–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Zotto, B.; Mumolo, G.; Pronio, A.M.; Montesani, C.; Tersigni, R.; Boirivant, M. TGF-Beta1 Production in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Differing Production Patterns in Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2003, 134, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, H.; Kakuta, Y.; Kinouchi, Y.; Kawai, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Nagao, M.; Naito, T.; Onodera, M.; Moroi, R.; Kuroha, M.; et al. Allele-Specific DNA Methylation of Disease Susceptibility Genes in Japanese Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanninelli, G. Smad3 Knock-out Mice as a Useful Model to Study Intestinal Fibrogenesis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 12, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihara, S.; Hirata, Y.; Koike, K. TGF-β in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Key Regulator of Immune Cells, Epithelium, and the Intestinal Microbiota. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 52, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, R.; Eick, L.; Hudjashov, G.; Läll, K.; Kanoni, S.; Wolford, B.N.; Wingfield, B.; Pain, O.; Wharrie, S.; Jermy, B.; et al. Evaluation of Polygenic Scoring Methods in Five Biobanks Shows Larger Variation between Biobanks than Methods and Finds Benefits of Ensemble Learning. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 111, 1431–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| UC | CD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysed Variables | n | Median (Q1–Q3) | n | Median (Q1–Q3) |

| Age at diagnosis [years] | 133 | 12.0 (7.8–14.7) | 153 | 12.6 (10.4–14.3) |

| Age at inclusion [years] | 127 | 14.8 (11.6–16.9) | 153 | 15.3 (13.6–17.1) |

| Duration of the disease [years] | 122 | 2.0 (0.4–3.8) | 151 | 2.3 (0.8–4.1) |

| Female | 49.3% | 42.2% | ||

| CRP at diagnosis [mg/L] | 124 | 2.4 (0.6–11.6) | 149 | 15.0 (2.4–31.2) |

| CRP at worst flare [mg/L] | 108 | 2.6 (0.8–12) | 130 | 16.8 (3–37.1) |

| Albumin at diagnosis [g/dL] | 114 | 4.1 (3.7–4.4) | 136 | 3.8 (3.5–4.2) |

| Albumin at worst flare [g/dL] | 103 | 4.2 (3.8–4.4) | 125 | 3.9 (3.5–4.2) |

| Mass Z-score at diagnosis | 126 | −0.5 (−1.1–0.3) | 144 | −0.8 (−1.4–0.1) |

| Height Z-score at diagnosis | 125 | 0 (−0.7–0.8) | 144 | −0.3 (−1.4–0.5) |

| BMI Z-score at diagnosis | 125 | −0.5 (−0.9–0.2) | 144 | −0.8 (−1.4–0) |

| Mass Z-score at worst flare | 108 | −0.5 (−1–0.4) | 125 | −0.8 (−1.4–0.2) |

| Height Z-score at worst flare | 109 | 0 (−0.7–0.6) | 126 | −0.4 (−1.3–0.3) |

| BMI Z-score at worst flare | 108 | −0.6 (−1–0.2) | 125 | −0.8 (−1.4–0.1) |

| PCDAI at diagnosis | 2 | 35 (32.5–37.5) | 136 | 30 (22.5–47.5) |

| PUCAI at diagnosis | 115 | 45 (30–60) | 3 | 40 (37.5–52.5) |

| PCDAI at worst flare | 1 | 120 | 40 (30–52.5) | |

| PUCAI at worst flare | 103 | 55.0 (36.3–65) | 2 | 56.3 (46.9–65.6) |

| UC | CD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysed Variables | n | Median (Q1–Q3) | n | Median (Q1–Q3) |

| Systemic steroids | 134 | 154 | ||

| Azathioprine | 133 | 154 | ||

| Methotrexate | 133 | 154 | ||

| Ciclosporin | 133 | 154 | ||

| Biologics | 134 | 154 | ||

| Infliximab | 131 | 153 | ||

| Adalimumab | 131 | 153 | ||

| Months from diagnosis to biological therapy | 34 | 14.3 (9.2–27) | 70 | 12.3 (6.1–26) |

| Age at first biological therapy | 35 | 11.0 (6.4–15.2) | 70 | 13.6 (12.4–15) |

| IBD-related surgery | 134 | 154 | ||

| Times hospitalised for IBD flare | 114 | 2 (1–3.8) | 130 | 1 (1–2) |

| Hospitalisations for IBD flare per year | 71 | 0.7 (0.3–1.4) | 95 | 0.5 (0.2–0.9) |

| Days hospitalised for IBD flare per year | 71 | 4.8 (1.6–9.2) | 95 | 4.3 (1.1–7.3) |

| Gene/SNP | Subgroup | Associated Clinical Parameters | Allele Type, Homozygous vs. Remaining Genotypes | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTBP3 rs11545200 | IBD | Age at diagnosis | minor | 0.0266 |

| IBD | Body mass Z-score at worst flare | minor | 0.0045 | |

| IBD | BMI Z-score at worst flare | minor | 0.0008 | |

| IBD | Biologics use | minor | 0.0323 | |

| IBD | Infliximab use | minor | 0.0267 | |

| UC | Infliximab use | minor | 0.0378 | |

| UC | Adalimumab use | minor | 0.0377 | |

| UC | Ciclosporin use | minor | 0.00577 | |

| CD | Disease duration | major | 0.0155 | |

| CD | Body mass Z-score at worst flare | major | 0.0075 | |

| CD | BMI Z-score at worst flare | major | 0.005 | |

| CD | Hospitalisations for flares | major | 0.0059 | |

| SMAD3 rs17293632 | IBD | Systemic corticosteroid use | major | 0.0137 |

| CD | Age at inclusion | minor | 0.0242 | |

| CD | Corticosteroid use | heterozygous | 0.0125 | |

| CD | Methotrexate use | minor | 0.0333 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brylak, J.; Szczepanik, M.; Nowak, J.K.; Jamka, M.; Glapa-Nowak, A.; Banaszkiewicz, A.; Radzikowski, A.; Szaflarska-Popławska, A.; Kwiecień, J.; Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk, U.; et al. From Polymorphisms to Phenotypes: SMAD3 rs17293632 and LTBP3 rs11545200 in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Genes 2025, 16, 1511. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121511

Brylak J, Szczepanik M, Nowak JK, Jamka M, Glapa-Nowak A, Banaszkiewicz A, Radzikowski A, Szaflarska-Popławska A, Kwiecień J, Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk U, et al. From Polymorphisms to Phenotypes: SMAD3 rs17293632 and LTBP3 rs11545200 in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1511. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121511

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrylak, Jan, Mariusz Szczepanik, Jan K. Nowak, Małgorzata Jamka, Aleksandra Glapa-Nowak, Aleksandra Banaszkiewicz, Andrzej Radzikowski, Anna Szaflarska-Popławska, Jarosław Kwiecień, Urszula Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk, and et al. 2025. "From Polymorphisms to Phenotypes: SMAD3 rs17293632 and LTBP3 rs11545200 in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease" Genes 16, no. 12: 1511. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121511

APA StyleBrylak, J., Szczepanik, M., Nowak, J. K., Jamka, M., Glapa-Nowak, A., Banaszkiewicz, A., Radzikowski, A., Szaflarska-Popławska, A., Kwiecień, J., Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk, U., Kawałkowska, E., Wiernicka, A., & Walkowiak, J. (2025). From Polymorphisms to Phenotypes: SMAD3 rs17293632 and LTBP3 rs11545200 in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Genes, 16(12), 1511. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121511