Genetic Diversity of Rhodiola quadrifida (Crassulaceae) in Altai High-Mountain Populations of Kazakhstan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

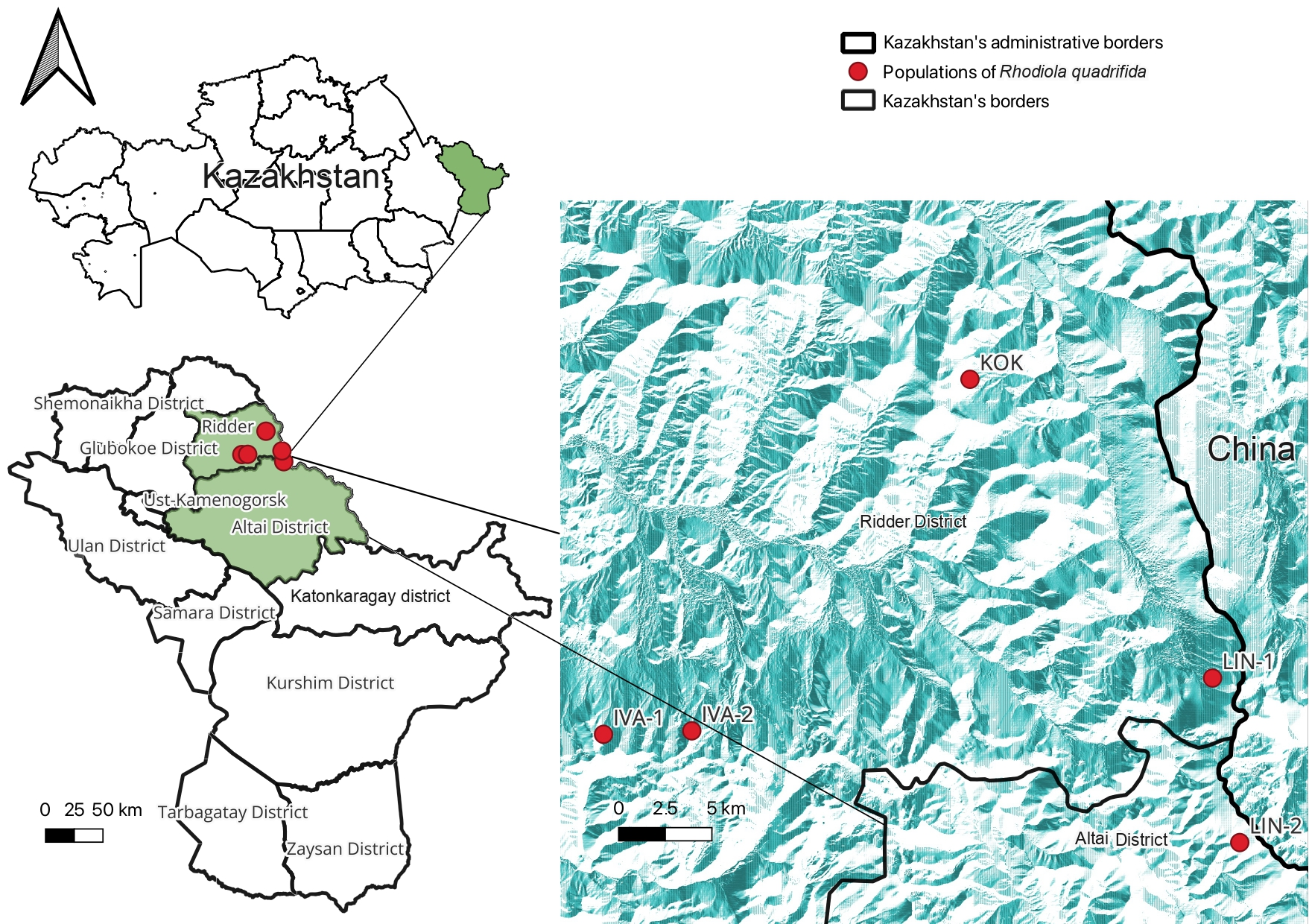

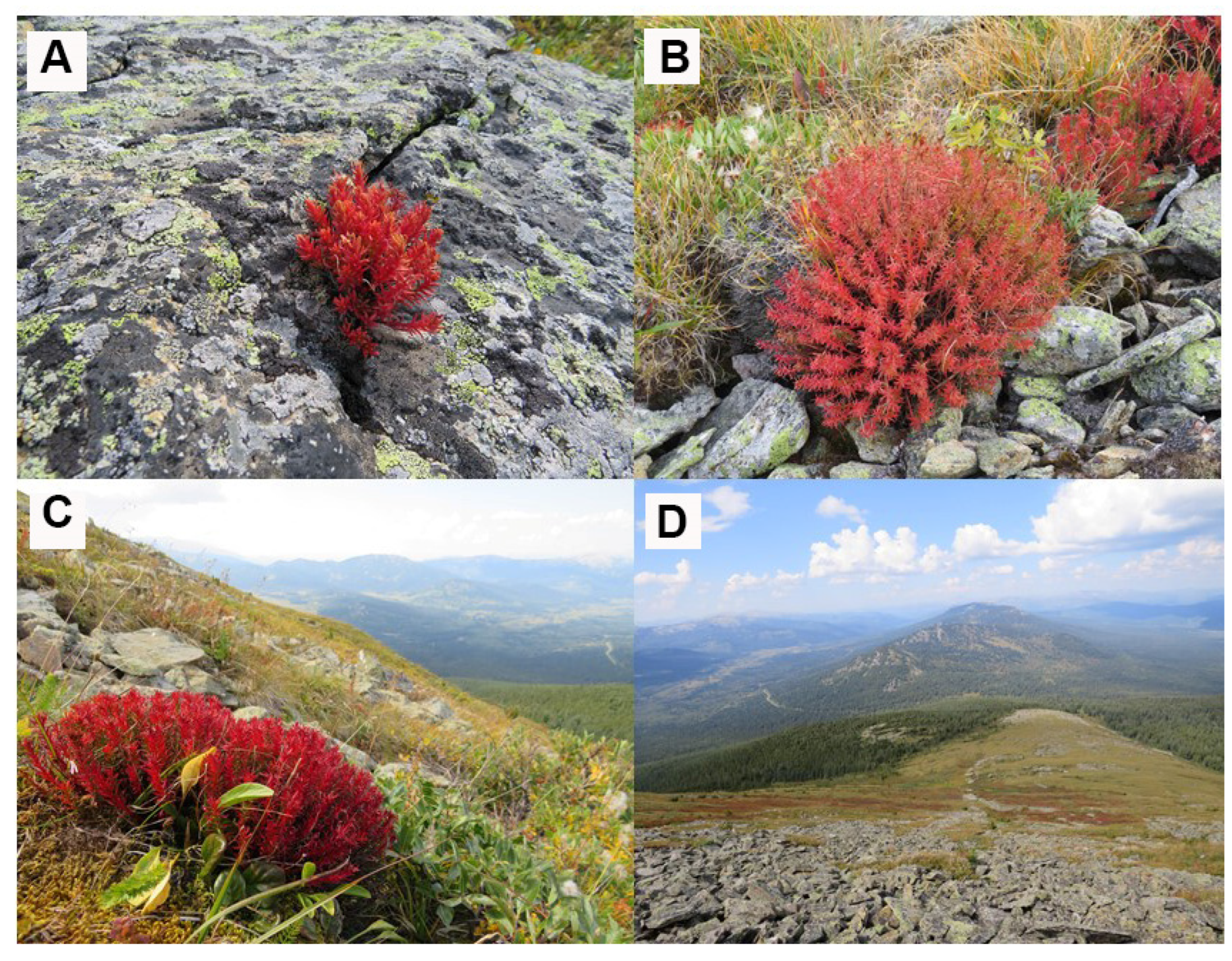

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Morphometric Characteristic Analysis of R. quadrifida Plants

2.3. Genetic Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

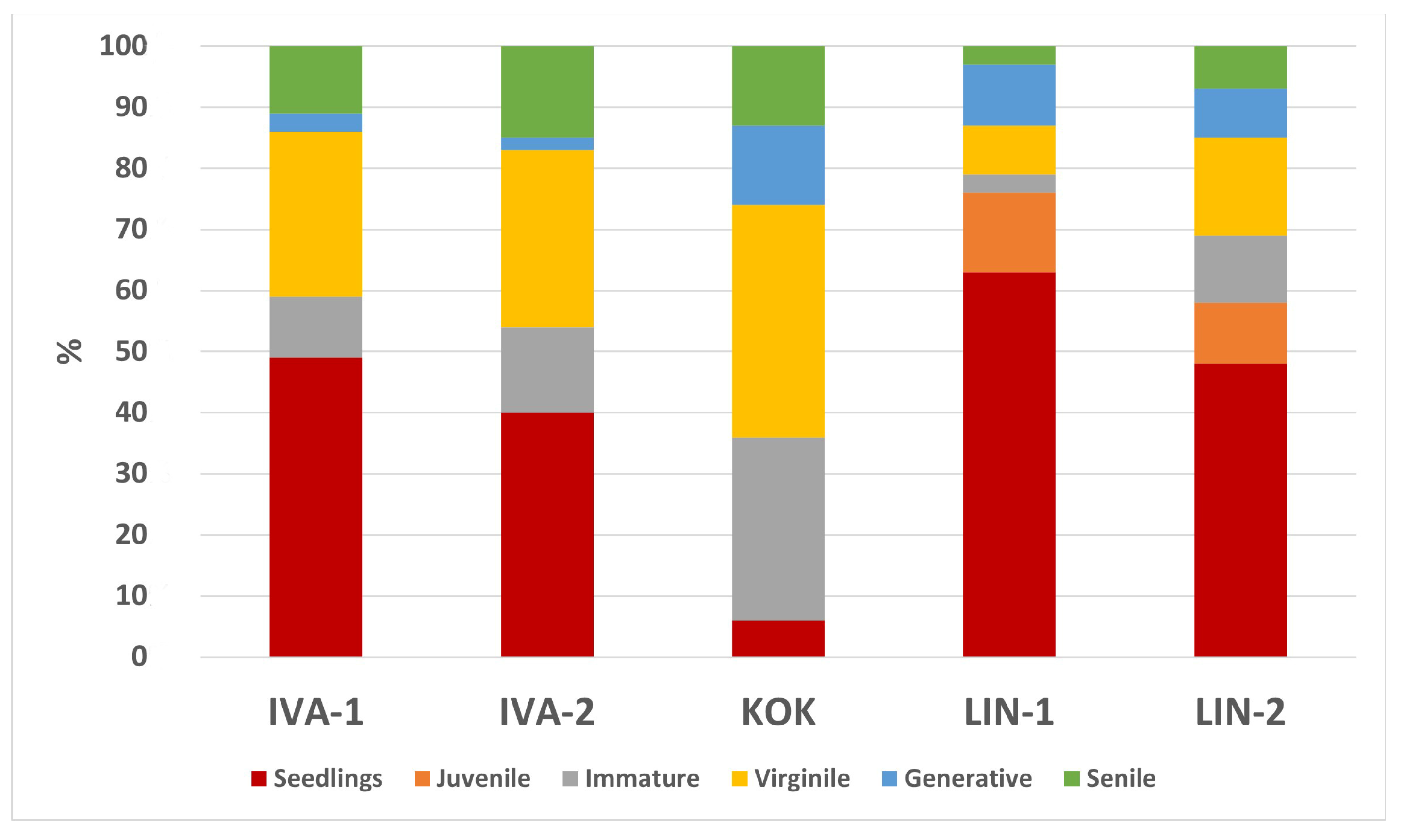

3. Results

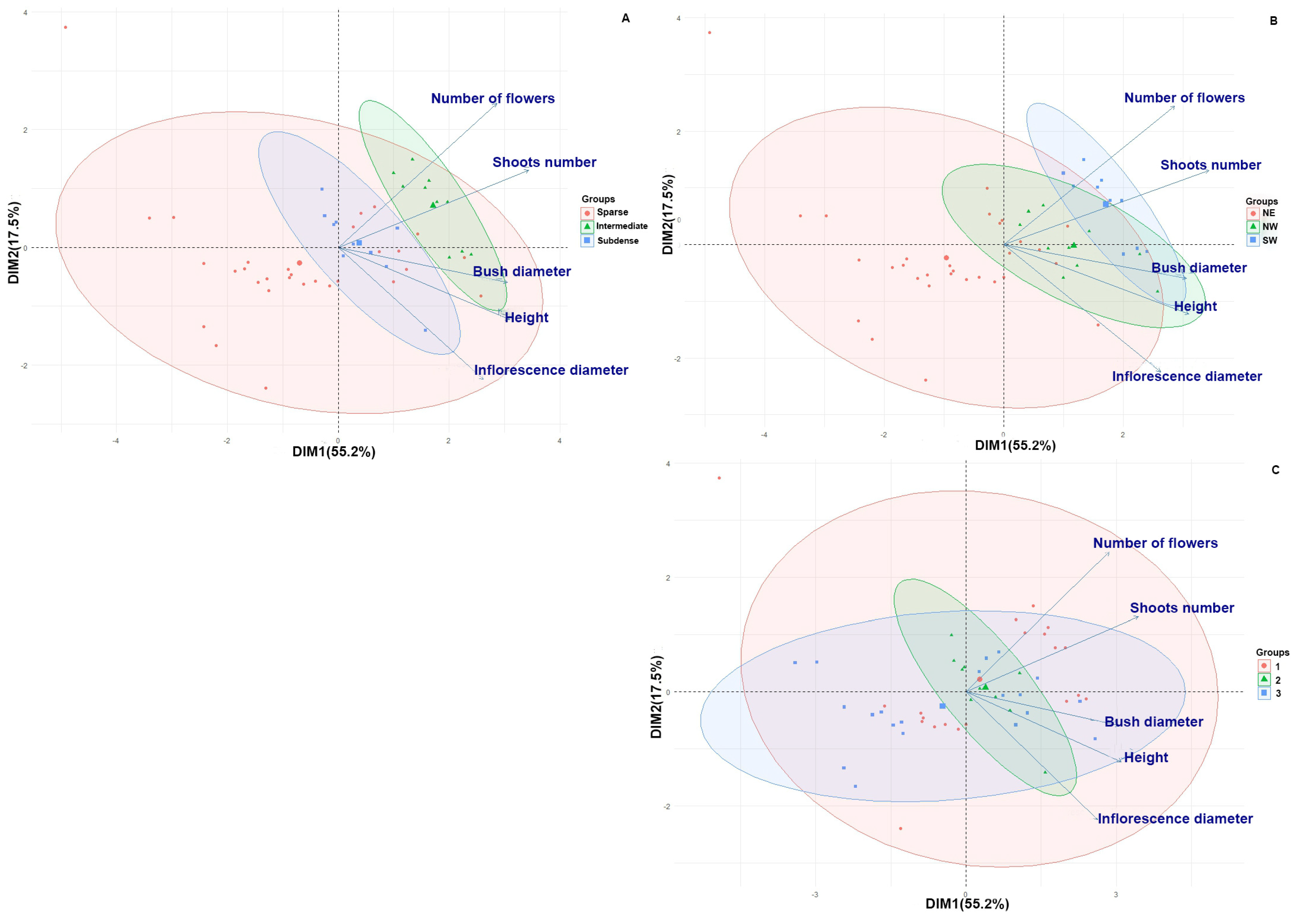

3.1. Evaluation of R. quadrifida Plant Morphometric Characteristics

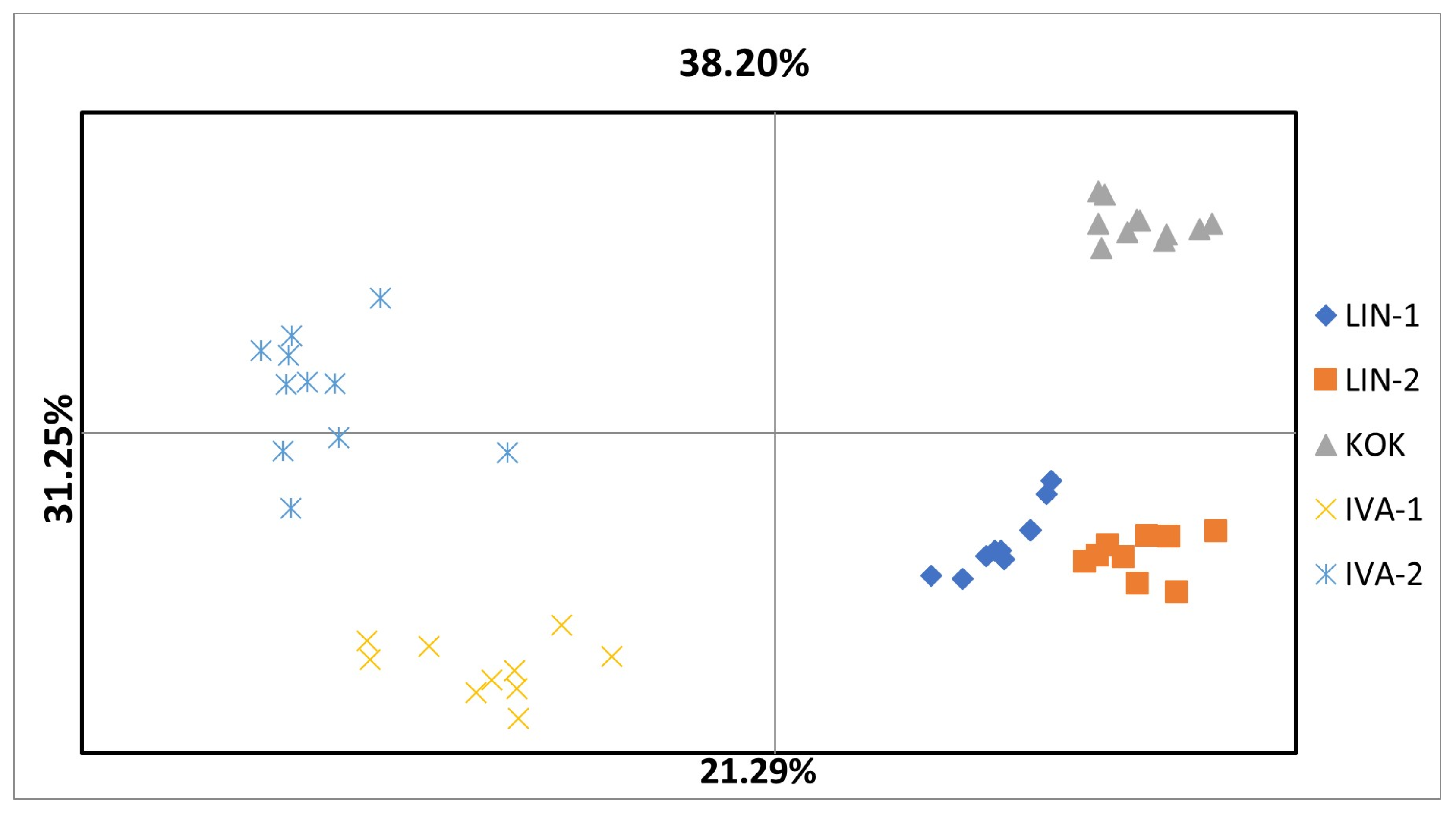

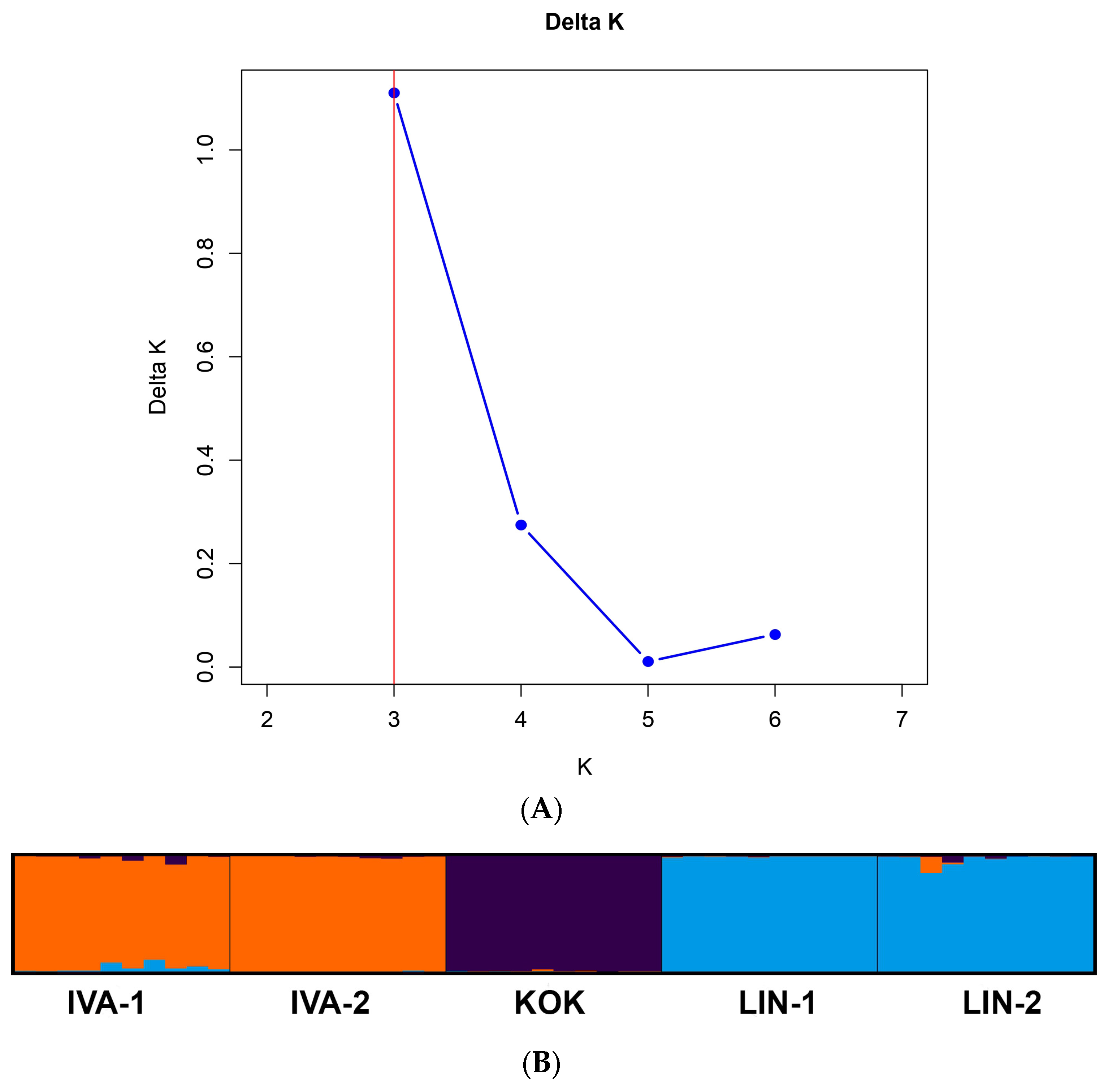

3.2. PBS-Profiling of R. quadrifida

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Yousef, G.G.; Grace, M.H.; Cheng, D.M.; Belolipov, I.V.; Raskin, I.; Lila, M.A. Comparative phytochemical characterization of three rhodiola species. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 2380–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Barrio, P.M.; Noreen, E.E.; Gilsanz-Estebaranz, L.; Lorenzo-Calvo, J.; Martinez-Ferran, M.; Pareja-Galeano, H. Rhodiola rosea supplementation on sports performance: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Phytother. Res. 2023, 37, 4414–4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Chen, S.; Chen, S.; Ge, X. Genetic variation within and among populations of Rhodiola alsia (crassulaceae) native to the tibetan plateau as detected by issr markers. Biochem. Genet. 2005, 43, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, N.; Jerold, F. Biocosmetics: Technological advances and future outlook. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 25148–25169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Nan, P.; Zhong, Y. Chemical composition of the essential oil of rhodiola quadrifida from xinjiang, china. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2005, 41, 418–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; You, J.; Wang, H. Analysis of five pharmacologically active compounds from rhodiola for natural product drug discovery with capillary electrophoresis. Chromatographia 2004, 60, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grech-Baran, M.; Syklowska-Baranek, K.; Pietrosiuk, A. Biotechnological approaches to enhance salidroside, rosin and its derivatives production in selected rhodiola spp. In vitro cultures. Phytochem. Rev. 2015, 14, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Shimada, H.; Shimoda, H.; Matsuda, H.; Yamahara, J.; Murakami, N. Rhodiocyanosides a and b, new antiallergic cyanoglycosides from chinese natural medicine “si lie hong jing tian”, the underground part of rhodiola quadrifida (pall.) fisch. Et mey. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1995, 43, 1245–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chiang, H.M.; Chen, H.C.; Wu, C.S.; Wu, P.Y.; Wen, K.C. Rhodiola plants: Chemistry and biological activity. J. Food Drug Anal. 2015, 23, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, H.; Wu, X.; Cao, J.; Peng, Y.; Wang, A.; Pei, J.; Xiao, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y. Rhodiola species: A comprehensive review of traditional use, phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicity, and clinical study. Med. Res. Rev. 2019, 39, 1779–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Shi, R.; Li, N.; Xu, Z.; Sun, M. Antioxidative effects of rhodiola genus: Phytochemistry and pharmacological mechanisms against the diseases. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 1692–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanova, A.; Malunova, M.; Salamaikina, S.; Selimov, R.; Solov’eva, A. Establishment of rhodiola quadrifida hairy roots and callus culture to produce bioactive compounds. Phyton 2021, 90, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antao, T.; Perez-Figueroa, A.; Luikart, G. Early detection of population declines: High power of genetic monitoring using effective population size estimators. Evol. Appl. 2011, 4, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoen, R.D.; Southgate, A.; Kiefer, G.; Shaw, R.G.; Wagenius, S. The conservation value of small population remnants: Variability in inbreeding depression and heterosis of a perennial herb, the narrow-leaved purple coneflower (Echinacea angustifolia). J. Hered. 2025, 116, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalendar, R.; Muterko, A.; Boronnikova, S. Retrotransposable elements: DNA fingerprinting and the assessment of genetic diversity. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2222, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zietkiewicz, E.; Rafalski, A.; Labuda, D. Genome fingerprinting by simple sequence repeat (ssr)-anchored polymerase chain reaction amplification. Genomics 1994, 20, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.; McClelland, M. Fingerprinting genomes using pcr with arbitrary primers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990, 18, 7213–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi Mandoulakani, B.; Yaniv, E.; Kalendar, R.; Raats, D.; Bariana, H.S.; Bihamta, M.R.; Schulman, A.H. Development of irap- and remap-derived scar markers for marker-assisted selection of the stripe rust resistance gene yr15 derived from wild emmer wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2015, 128, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosid, E.; Brodsky, L.; Kalendar, R.; Raskina, O.; Belyayev, A. Diversity of long terminal repeat retrotransposon genome distribution in natural populations of the wild diploid wheat aegilops speltoides. Genetics 2012, 190, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalendar, R.; Shevtsov, A.; Otarbay, Z.; Ismailova, A. In silico pcr analysis: A comprehensive bioinformatics tool for enhancing nucleic acid amplification assays. Front. Bioinform. 2024, 4, 1464197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalendar, R.; Amenov, A.; Daniyarov, A. Use of retrotransposon-derived genetic markers to analyse genomic variability in plants. Funct. Plant Biol. 2018, 46, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvas, Y.E.; Marakli, S.; Kaya, Y.; Kalendar, R. The power of retrotransposons in high-throughput genotyping and sequencing. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1174339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalendar, R.; Kairov, U. Genome-wide tool for sensitive de novo identification and visualisation of interspersed and tandem repeats. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 2024, 18, 11779322241306391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyayev, A.; Kalendar, R.; Brodsky, L.; Nevo, E.; Schulman, A.H.; Raskina, O. Transposable elements in a marginal plant population: Temporal fluctuations provide new insights into genome evolution of wild diploid wheat. Mob. DNA 2010, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, R.; McLean, K.; Flavell, A.J.; Pearce, S.R.; Kumar, A.; Thomas, B.B.; Powell, W. Genetic distribution of bare-1-like retrotransposable elements in the barley genome revealed by sequence-specific amplification polymorphisms (s-sap). Mol. Gen. Genet. 1997, 253, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Vinod, K.K.; Kalendar, R.; Yrjälä, K.; Zhou, M. Development and deployment of high-throughput retrotransposon-based markers reveal genetic diversity and population structure of asian bamboo. Forests 2019, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalendar, R.; Antonius, K.; Smykal, P.; Schulman, A.H. Ipbs: A universal method for DNA fingerprinting and retrotransposon isolation. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010, 121, 1419–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalendar, R.; Schulman, A.H. Irap and remap for retrotransposon-based genotyping and fingerprinting. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2478–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khapilina, O.; Turzhanova, A.; Zhumagul, M.; Tagimanova, D.; Raiser, O.; Kubentayev, S.; Shevtsov, V.; Hohn, M. Retrotransposon-based genetic diversity of Rhodiola rosea L. (crassulaceae) from kazakhstan altai. Diversity 2025, 17, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanov, A.; Zvyagin, A.; Daniyarov, A.; Kalendar, R.; Troshin, L. Genetic analysis of the grapevine genotypes of the russian vitis ampelographic collection using ipbs markers. Genetica 2019, 147, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terletskaya, N.V.; Turzhanova, A.S.; Khapilina, O.N.; Zhumagul, M.Z.; Meduntseva, N.D.; Kudrina, N.O.; Korbozova, N.K.; Kubentayev, S.A.; Kalendar, R. Genetic diversity in natural populations of rhodiola species of different adaptation strategies. Genes 2023, 14, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Gao, H.; Tsering, T.; Shi, S.; Zhong, Y. Determination of genetic variation in rhodiola crenulata from the hengduan mountains region, china using inter-simple sequence repeats. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2006, 29, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.-F.; Zu, Y.-G.; Yan, X.-F.; Zhou, F.-J. Genetic structure of endangered rhodiola sachalinensis. Conserv. Genet. 2003, 4, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, S.C. Influences of clonality on plant sexual reproduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 8859–8866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzyski, J.R.; Stieha, C.R.; Nicholas McLetchie, D. The impact of asexual and sexual reproduction in spatial genetic structure within and between populations of the dioecious plant Marchantia inflexa (marchantiaceae). Ann. Bot. 2018, 122, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basharina, O.Y. Methodology for collecting, processing, and analyzing socio-economic data in the framework of mathematical and information modeling objects at the baikal natural territory. Mod. High Technol. 2022, 10.17513/snt.39227, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalendar, R.; Boronnikova, S.; Seppanen, M. Isolation and purification of DNA from complicated biological samples. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2222, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uranov, A.J. The vital state of the species in the plant community. Bulletin MOIP 1969, 1, 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Kalendar, R.; Ivanov, K.I.; Samuilova, O.; Kairov, U.; Zamyatnin, A.A., Jr. Isolation of high-molecular-weight DNA for long-read sequencing using a high-salt gel electroelution trap. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 17818–17825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalendar, R.; Ivanov, K.I.; Akhmetollayev, I.; Kairov, U.; Samuilova, O.; Burster, T.; Zamyatnin, A.A., Jr. An improved method and device for nucleic acid isolation using a high-salt gel electroelution trap. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 15526–15530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalendar, R. Comprehensive web-based platform for advanced pcr design, genotyping, synthetic biology, molecular diagnostics, and sequence analysis. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2025, 36, 102716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigollet, P.; Tsybakov, A. Exponential screening and optimal rates of sparse estimation. Ann. Stat. 2011, 39, 731–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software structure: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopelman, N.M.; Mayzel, J.; Jakobsson, M.; Rosenberg, N.A.; Mayrose, I. Clumpak: A program for identifying clustering modes and packaging population structure inferences across k. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2015, 15, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peakall, R.O.D.; Smouse, P.E. Genalex 6: Genetic analysis in excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Molecular Ecology Notes 2005, 6, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Lou, A. Population genetic diversity and structure of a naturally isolated plant species, Rhodiola dumulosa (crassulaceae). PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerbay, M.; Khapilina, O.N.; Turzhanova, A.S.; Otradnykh, I.G.; Sedina, I.A.; Mamirova, A.; Korbozova, N.K.; Magzumova, S.; Ashimuly, K.; Kudrina, N.O.; et al. Metabolomic adaptations and genetic polymorphism in ecopopulations of rhodiola linearifolia boriss. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1570411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.; Wen, J.; Jiao, Z.; Bian, Z.; Zhong, S.; Zhu, W.; Cao, B.; Li, H.; Du, Y.; Xiao, Q.; et al. Modeling the topographic effect on directional anisotropies of land surface temperature from thermal remote sensing. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 4, 0226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, W.; Xu, Y.; Liang, Z.; Hu, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y. Quality evaluation of randomized controlled trials of rhodiola species: A systematic review. Evid. Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021, 2021, 9989546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Ramirez, J.; Venn, S.E. Seeds and seedlings in a changing world: A systematic review and meta-analysis from high altitude and high latitude ecosystems. Plants 2021, 10, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, C.L.; Hamrick, J.L.; Donovan, L.A.; Mauricio, R. Unexpectedly high clonal diversity of two salt marsh perennials across a severe environmental gradient. Ecol. Lett. 2004, 7, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xie, D.; Wang, H.; Zhao, A.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, X.; Li, T.; Zhao, J. Effects of highland environments on clonal diversity in aquatic plants: An interspecific comparison study on the qinghai-tibetan plateau. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1040282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisch, C.; Schurm, S.; Poschlod, P. Spatial genetic structure and clonal diversity in an alpine population of Salix herbacea (salicaceae). Ann. Bot. 2007, 99, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madlung, A.; Comai, L. The effect of stress on genome regulation and structure. Ann. Bot. 2004, 94, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisch, C.; Anke, A.; Röhl, M. Molecular variation within and between ten populations of Primula farinosa (primulaceae) along an altitudinal gradient in the northern alps. Basic. Appl. Ecol. 2005, 6, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population | Phytocenosis | Gathering Place | Coordinates | Height Limit, m Above Level m | Projective Cover (%) | Slope | Ground Cover (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude | Longitude | |||||||

| IVA-1 | Dryas oxydontha, Carex capillaris, Carex rupestris, Viola biflora, Thermopsis alpina, Silene graminifolia, Koenigia alpina Minuartia verna, Patrinia sibirica. | Ivanovsky ridge | 50°18′41.1 | 83°47′19.0 | 1900–2400 | 45,780 (Sparse) | NW | 100 (Dense) |

| IVA-2 | Anemonastrum crinitum, Bistorta elliptica, Dracocephalum grandiflorum, Pachypleurum alpinum, Bergenia crassifolia, Gentiana algida, G. grandiflora, Oxytropis alpina, Hedysarum austrosibiricum, Festuca borissii, F. kryloviana, Thermopsis alpina, Dryas oxyodonta, Patrinia sibirica, Huperzia selago, Woodsia heterophylla, Valeriana capitata, Dracocephalum imberbe, Betula fruticosa. | Ivanovsky ridge, upper reaches of the Bolshaya Poperechka river | 50°18′47.1 | 83°51′18.1 | 2000–2300 | 42,278 (Sparse) | NE | 100 (Dense) |

| KOK | Hierochloe odorata, Silene graminifolia, Hedysarum austrosibiricum, Dryas oxyodonta, Trisetum spicatum, Koeleria ledebourii, Gentiana algida, Bistorta vivipara, Thermopsis alpina, Pedicularis oederi, Chulzia crinita, Patrinia sibirica, Pachypleurum alpinum, Allium pumilum, Eremogone formosa, Lloydia serotina. | Koksinsky ridge | 50°28′53.5 | 84°03′49.8 | 1950–2000 | 35 (Intermediate) | SW | 90 (Dense) |

| LIN-1 | Aster alpinus, Poa attenuata, Bergenia crassifolia, Bupleurum longiinvolucratum, Epilobium lactiflorum, Patrinia sibirica, Allium lineare, Ligularia glauca, Aconitum anthoroideum, Sedum ewersii, Bistorta elliptica. | Lineisky ridge | 50°20′18.4 | 84°14′46.1 | 1830–2200 | 50 (Subdense) | NE | 95 (Dense) |

| LIN-2 | Bupleurum longiinvolucratum, Gentiana algida, G. grandiflora, Crepis chrysantha, Schulzia crinita Pedicularis amoena, P. oederi, Huperzia selago, Dracocephalum grandiflorumpeжe Silene graminifolia, Dracocephalum imberbe, Pachypleurum alpinum, Bergenia crassifolia. | Lineisky ridge, Latunikha River | 0°15′33.8 | 84°15′59.7 | 2139 | 5–7 (Sparse) | SW | 30 (Sparse) |

| Primer ID | Sequence | Tm °C | GC% | LC% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2220 | ACCTGGCTCATGATGCCA | 55 | 55.6 | 86 |

| 2221 | ACCTAGCTCACGATGCCA | 55 | 55.6 | 92 |

| 2222 | ACTTGGATGCCGATACCA | 53 | 50.0 | 90 |

| 2228 | CATTGGCTCTTGATACCA | 55 | 44.4 | 90 |

| 2229 | CGACCTGTTCTGATACCA | 53 | 50.0 | 90 |

| 2230 | TCTAGGCGTCTGATACCA | 53 | 50.0 | 94 |

| 2232 | AGAGAGGCTCGGATACCA | 55 | 55.6 | 86 |

| 2240 | AACCTGGCTCAGATGCCA | 55 | 55.6 | 87 |

| 2241 | ACCTAGCTCATCATGCCA | 53 | 50.0 | 89 |

| 2300 | CACCGGGCTCTGATACCA | 57 | 61.1 | 90 |

| 2395 | TCCCCAGCGGAGTCGCCA | 62 | 72.2 | 82 |

| Population | Plant Height | Bush Diameter | Number of Shoots per Bush | Inflorescence Diameter | Number of Flowers in an Inflorescence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVA-1 | 8.28 ± 1.36 | 17.6 ± 2.56 | 45.7 ± 3.39 | 1.97 ± 0.24 | 4.74 ± 0.62 |

| IVA-2 | 6.23 ± 0.25 | 12.7 ± 0.50 | 36.4 ± 2.91 | 1.71 ± 0.15 | 3.19 ± 0.27 |

| KOK | 9.58 ± 0.89 | 15.1 ± 1.03 | 45.1 ± 3.58 | 1.97 ± 0.36 | 6.86 ± 0.33 |

| LIN-1 | 8.67 ± 1.16 | 17.3 ± 1.43 | 24.4 ± 3.05 | 1.69 ± 0.28 | 4.87 ± 0.46 |

| LIN-2 | 9.59 ± 0.31 | 12.4 ± 0.69 | 26.5 ± 1.58 | 1.80 ± 0.13 | 4.54 ± 0.43 |

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.05 | <0.001 |

| Trait | Projection Coverage F (p); Tukey sig. | Slope F (p); Tukey Sig. | Ground Vegetation F (p); Tukey Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height | 2.10 (p > 0.05); | 0.83 (p > 0.05); | 1.42 (p > 0.05); |

| Bush diameter | 1.22 (p > 0.05); | 4.09 (p < 0.05); NW > NE | 4.16 (p < 0.05); Dense > Sparse |

| Shoot number | 13.43 (p < 0.001); Int > Sparse; Int > Subdense | 64.67 (p < 0.001); NW > NE; SW > NE | 20.80 (p < 0.001); Dense > Sparse |

| Inflorescence diameter | 1.87 (p > 0.05); | 1.91 (p > 0.05); | 0.56 (p > 0.05); |

| Flowers number | 9.78 (p < 0.001); Int > Sparse; Int > Subdense | 8.48 (p < 0.001); SW > NE; SW > NW | 0.10 (p > 0.05); |

| Pop | Na | Ne | I | He | uHe | p (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVA-1 | 1.264 | 1.239 | 0.247 | 0.154 | 0.162 | 60.98 |

| IVA-2 | 1.020 | 1.198 | 0.194 | 0.124 | 0.130 | 45.12 |

| KOK | 1.041 | 1.204 | 0.200 | 0.128 | 0.134 | 45.53 |

| LIN-1 | 1.427 | 1.349 | 0.324 | 0.212 | 0.223 | 67.07 |

| LIN-2 | 1.512 | 1.342 | 0.320 | 0.207 | 0.218 | 71.95 |

| Mean | 1.253 | 1.266 | 0.257 | 0.165 | 0.173 | 58.13 |

| Source | df | SS | MS | Est. Var. | % | PhiPT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among Pops | 4 | 920.000 | 230.000 | 20.261 | 43% | 0.425 |

| Within Pops | 45 | 1232.700 | 27.393 | 27.393 | 57% | |

| Total | 49 | 2152.700 | 47.654 | 100% |

| IVA-1 | IVA-2 | KOK | LIN-1 | LIN-2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.000 | IVA-1 | ||||

| 0.913 | 1.000 | IVA-2 | |||

| 0.880 | 0.866 | 1.000 | KOK | ||

| 0.821 | 0.773 | 0.747 | 1.000 | LIN-1 | |

| 0.828 | 0.783 | 0.779 | 0.921 | 1.000 | LIN-2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khapilina, O.; Turzhanova, A.; Zhumagul, M.; Magzumova, S.; Raiser, O.; Tagimanova, D.; Kubentayev, S.; Shevtsov, V. Genetic Diversity of Rhodiola quadrifida (Crassulaceae) in Altai High-Mountain Populations of Kazakhstan. Genes 2025, 16, 1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121449

Khapilina O, Turzhanova A, Zhumagul M, Magzumova S, Raiser O, Tagimanova D, Kubentayev S, Shevtsov V. Genetic Diversity of Rhodiola quadrifida (Crassulaceae) in Altai High-Mountain Populations of Kazakhstan. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121449

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhapilina, Oxana, Ainur Turzhanova, Moldir Zhumagul, Saule Magzumova, Olesya Raiser, Damelya Tagimanova, Serik Kubentayev, and Vladislav Shevtsov. 2025. "Genetic Diversity of Rhodiola quadrifida (Crassulaceae) in Altai High-Mountain Populations of Kazakhstan" Genes 16, no. 12: 1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121449

APA StyleKhapilina, O., Turzhanova, A., Zhumagul, M., Magzumova, S., Raiser, O., Tagimanova, D., Kubentayev, S., & Shevtsov, V. (2025). Genetic Diversity of Rhodiola quadrifida (Crassulaceae) in Altai High-Mountain Populations of Kazakhstan. Genes, 16(12), 1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121449