Hepcidin from the Chinese Spiny Frog (Quasipaa spinosa) Integrates Membrane-Disruptive Antibacterial Activity with Macrophage-Mediated Protection Against Elizabethkingia miricola

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Analysis of QsHep cDNA

2.3. QsHep Expression Profiles

2.4. RT-qPCR

2.5. Antibacterial Assay

2.6. Lactate Dehydrogenase Release Assay

2.7. Cell Preparation

2.8. CCK-8 Assay

2.9. Chemotaxis Assay

2.10. Phagocytosis Assay

2.11. Respiratory Burst Assay

2.12. Frog Survival Assays

2.13. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

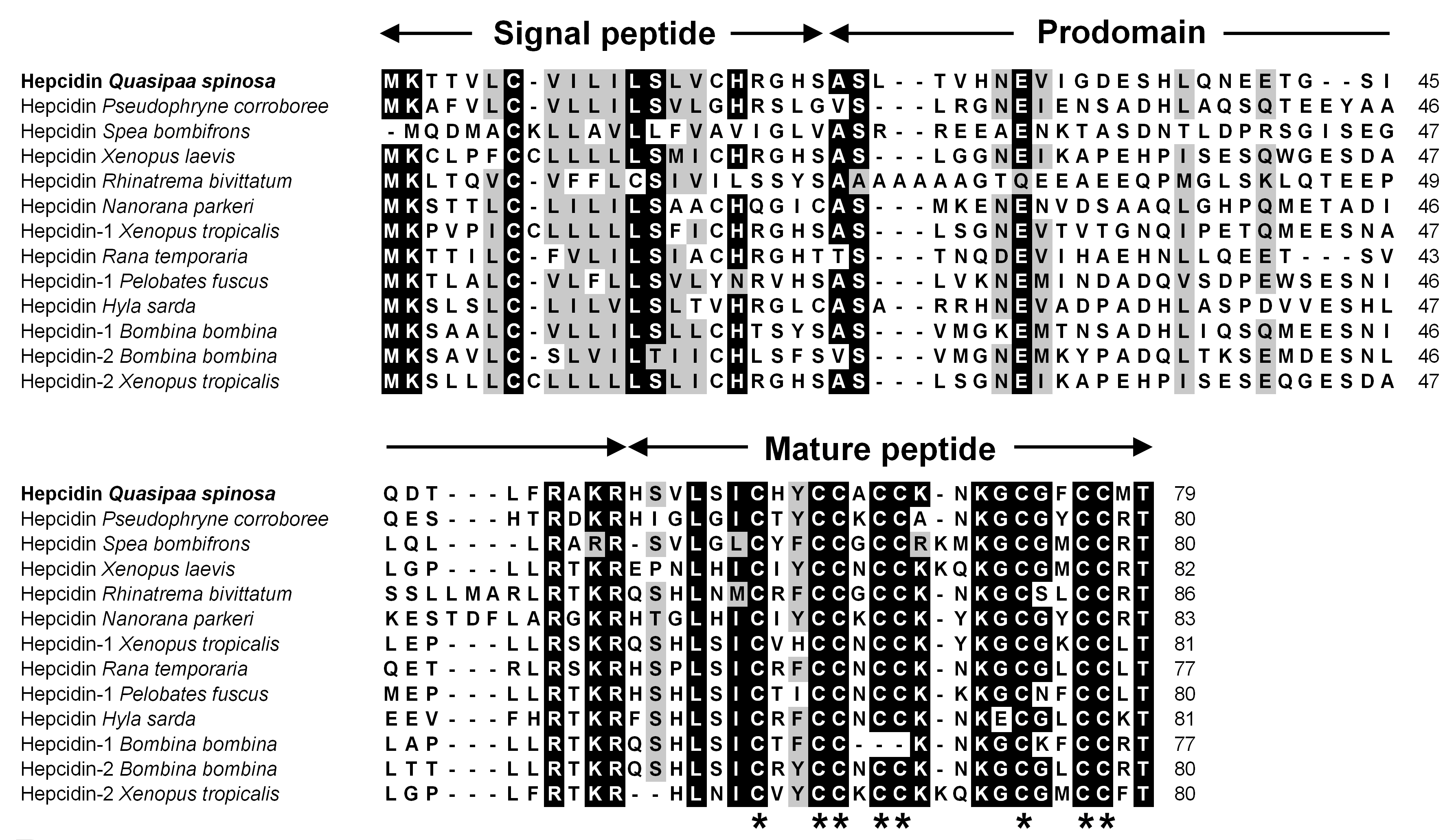

3.1. Characterization of QsHep

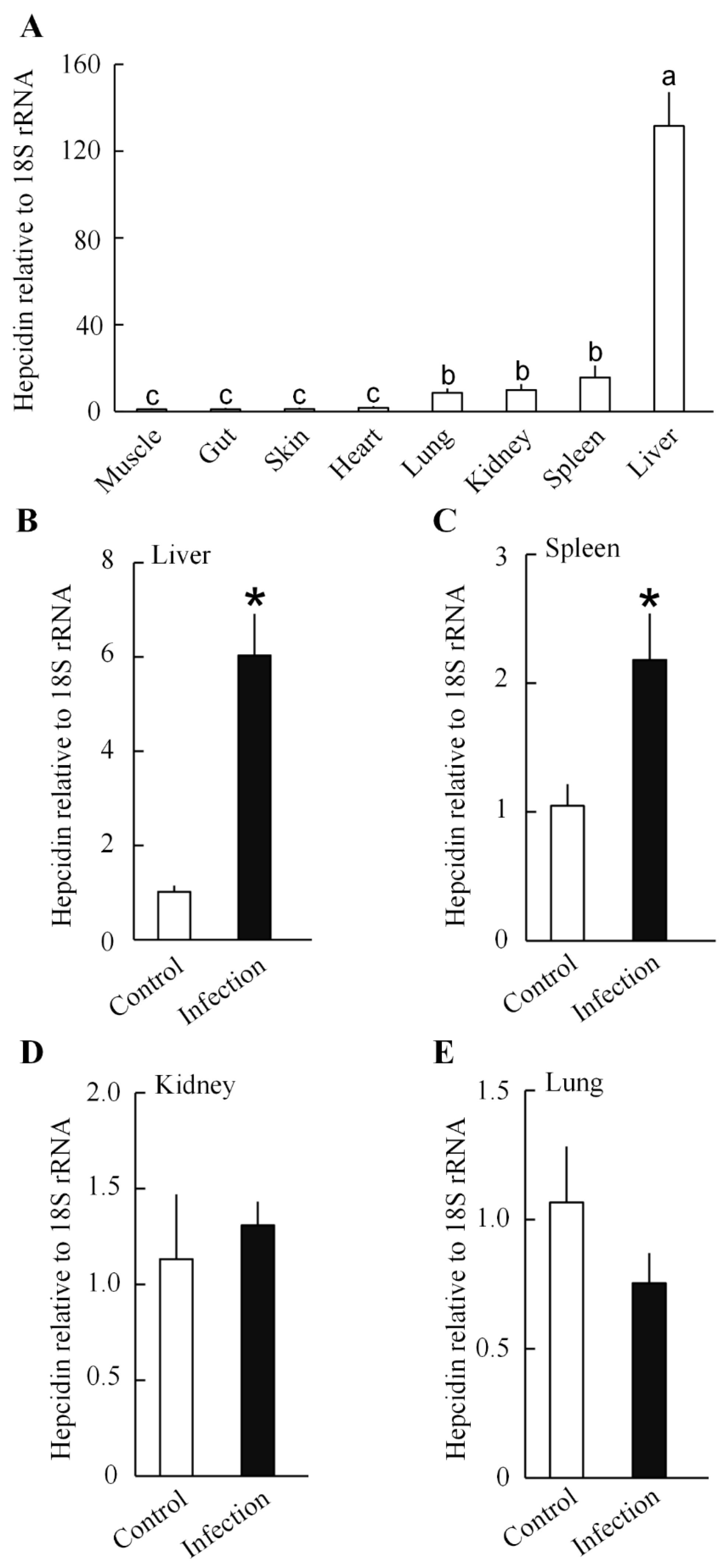

3.2. The Expression of QsHep

3.3. QsHep In Vitro Antibacterial Activity

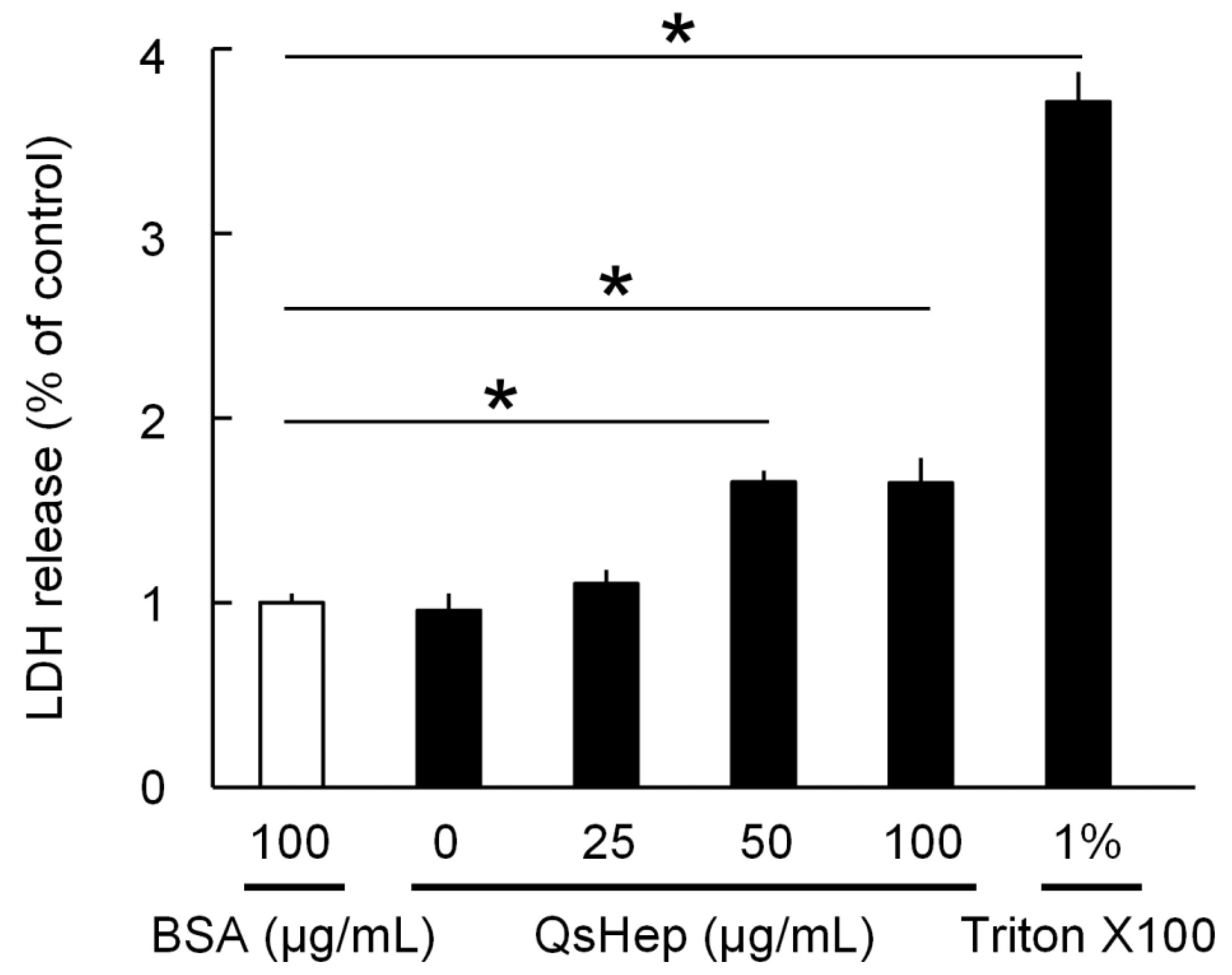

3.4. Effects of QsHep on Elizabethkingia miricola Cell Membrane Integrity

3.5. Effect of QsHep on Macrophage Viability and Chemotaxis

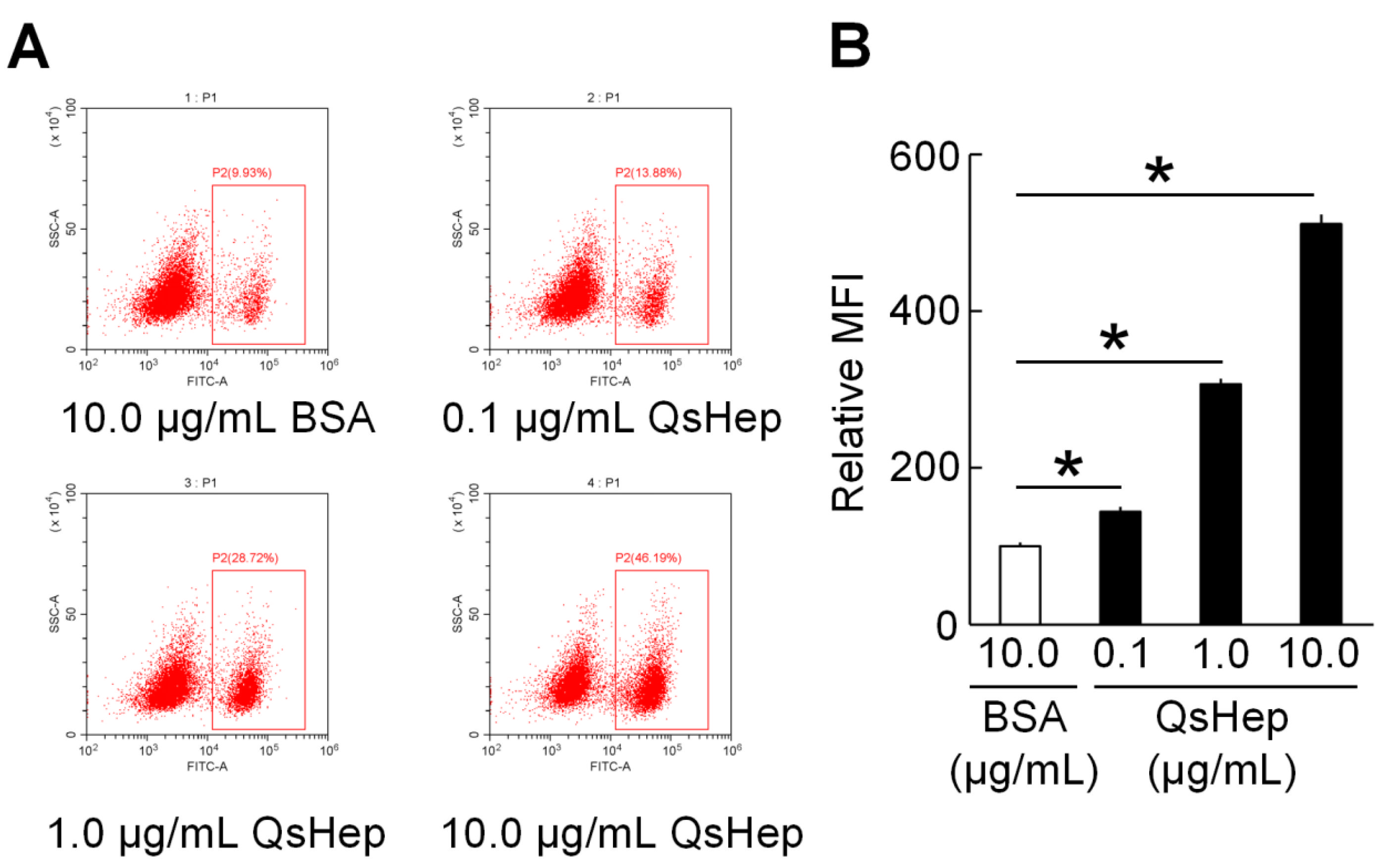

3.6. Effect of QsHep on the Phagocytosis of Macrophages

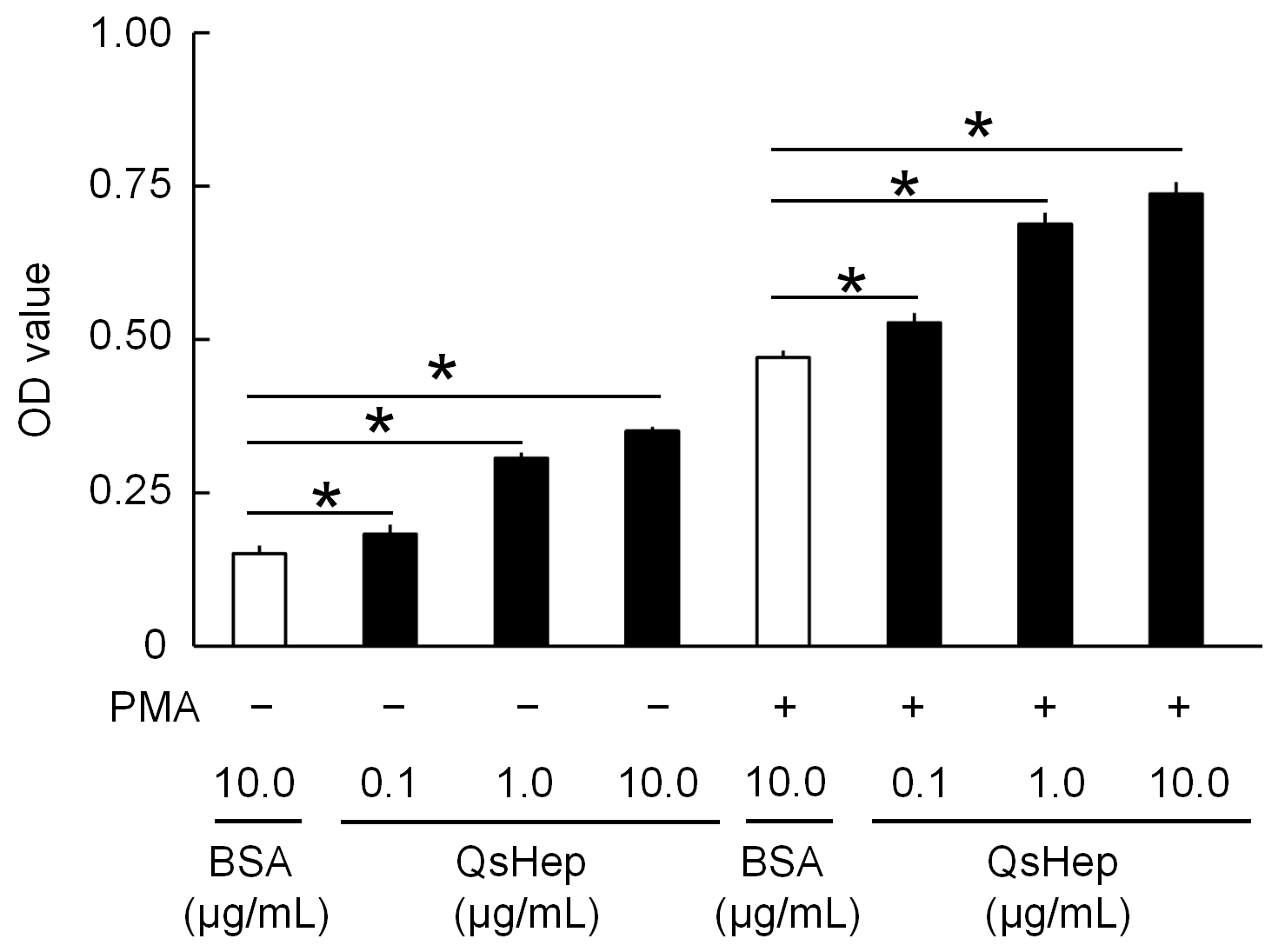

3.7. Effect of QsHep on Macrophage Respiratory Burst

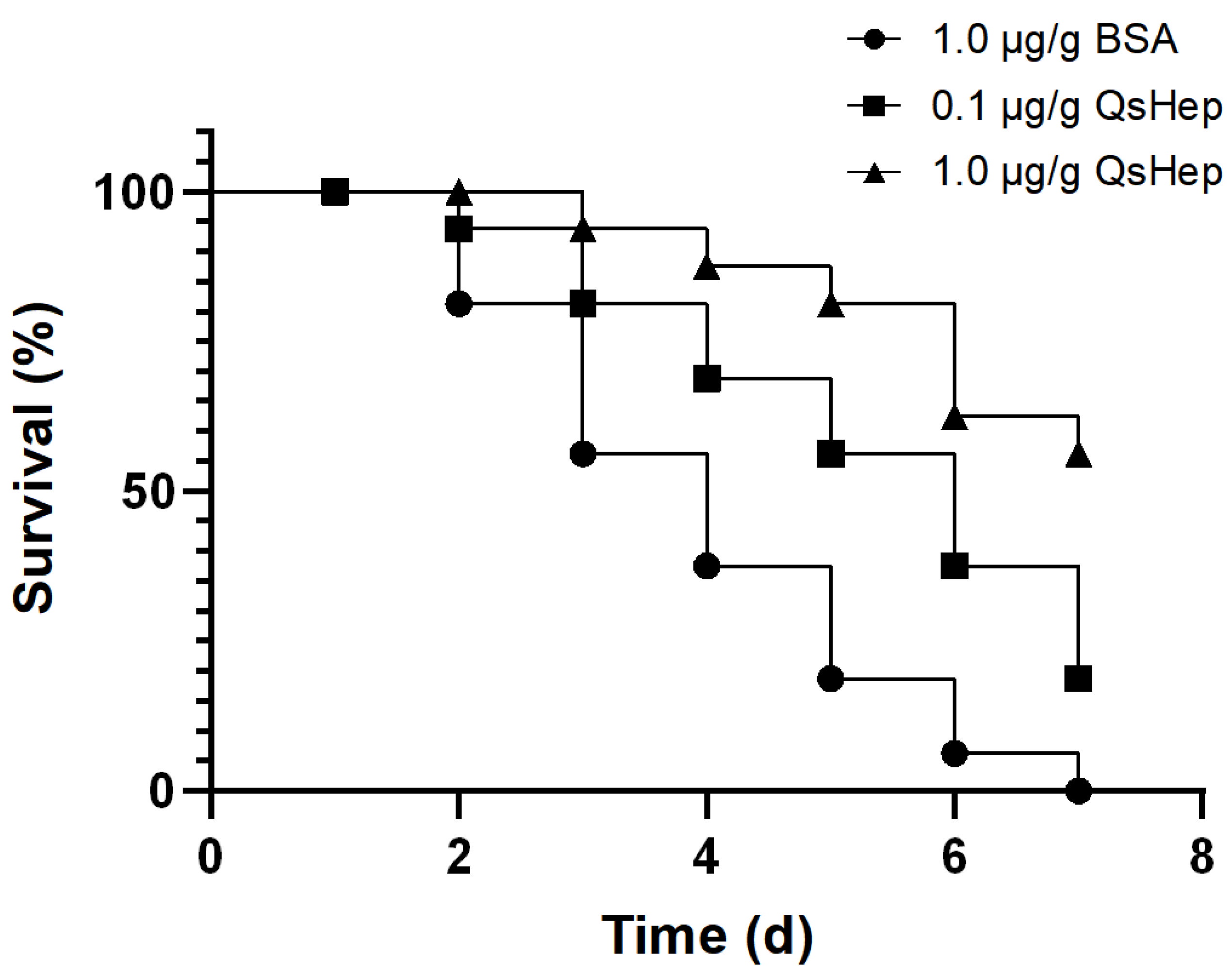

3.8. Effect of the QsHep on Frog Survival After Elizabethkingia miricola Challenge

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Hoek, M.L. Antimicrobial peptides in reptiles. Pharmaceuticals 2014, 7, 723–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawrot, R.; Barylski, J.; Nowicki, G.; Broniarczyk, J.; Buchwald, W.; Goździcka-Józefiak, A. Plant antimicrobial peptides. Folia Microbiol. 2014, 59, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehrer, R.I.; Ganz, T. Antimicrobial peptides in mammalian and insect host defence. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1999, 11, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zasloff, M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 2002, 415, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Samperio, P. Recent advances in the field of antimicrobial peptides in inflammatory diseases. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2013, 2, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, G.; Beckloff, N.; Weinberg, A.; Kisich, K.O. The roles of antimicrobial peptides in innate host defense. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009, 15, 2377–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savini, F.; Loffredo, M.R.; Troiano, C.; Bobone, S.; Malanovic, N.; Eichmann, T.O.; Caprio, L.; Canale, V.C.; Park, Y.; Mangoni, M.L.; et al. Binding of an antimicrobial peptide to bacterial cells: Interaction with different species, strains and cellular components. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2020, 1862, 183291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, A.A.; Ren, D. Antimicrobial peptides. Pharmaceuticals 2013, 6, 1543–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, P.Y.; Khanum, R. Antimicrobial peptides as potential anti-biofilm agents against multidrug-resistant bacteria. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2017, 50, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mygind, P.H.; Fischer, R.L.; Schnorr, K.M.; Hansen, M.T.; Sönksen, C.P.; Ludvigsen, S.; Raventós, D.; Buskov, S.; Christensen, B.; De Maria, L.; et al. Plectasin is a peptide antibiotic with therapeutic potential from a saprophytic fungus. Nature 2005, 437, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liu, Q.; Wang, D.; Li, J. Characterization and antimicrobial mechanism of CF-14, a new antimicrobial peptide from the epidermal mucus of catfish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 92, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, A.; Neitz, S.; Mägert, H.J.; Schulz, A.; Forssmann, W.G.; Schulz-Knappe, P.; Adermann, K. LEAP-1, a novel highly disulfide-bonded human peptide, exhibits antimicrobial activity. FEBS Lett. 2000, 480, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.H.; Valore, E.V.; Waring, A.J.; Ganz, T. Hepcidin, a urinary antimicrobial peptide synthesized in the liver. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 7806–7810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, W.; Xu, Y.W.; Chen, R.Y.; Xu, Q. Sequence analysis of hepcidin in barbel steed (Hemibarbus labeo): QSHLS motif confers hepcidin iron-regulatory activity but limits its antibacterial activity. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2021, 114, 103845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Li, B.; Yu, R.; Xu, W.; Liu, X.; Su, J.; Yuan, G. Hepcidin contributes to largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) against bacterial infections. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 131144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, G.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Yang, H.; Zhou, A.; Xie, S.; Fan, L.; Wang, M.; et al. Characterization, expression, and functional analysis of the Northern Snakehead (Channa argus) hepcidin. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2023, 17, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Li, Y.W.; Xie, M.Q.; Li, A.X. Molecular cloning, recombinant expression and antibacterial activity analysis of hepcidin from Siamese crocodile (Crocodylus siamensis). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012, 163, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocquellet, A.; Le Senechal, C.; Garbay, B. Importance of the disulfide bridges in the antibacterial activity of human hepcidin. Peptides 2012, 36, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisetta, G.; Petruzzelli, R.; Brancatisano, F.L.; Esin, S.; Vitali, A.; Campa, M.; Batoni, G. Antimicrobial activity of human hepcidin 20 and 25 against clinically relevant bacterial strains: Effect of copper and acidic pH. Peptides 2010, 31, 1995–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, G.; Bennoun, M.; Devaux, I.; Beaumont, C.; Grandchamp, B.; Kahn, A.; Vaulont, S. Lack of hepcidin gene expression and severe tissue iron overload in upstream stimulatory factor 2 (USF2) knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 8780–8785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyoral, D.; Jiri, P. Therapeutic potential of hepcidin—The master regulator of iron metabolism. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 115, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Gan, Z.S.; Ma, W.; Xiong, H.T.; Li, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.Z.; Du, H.H. Synthetic porcine hepcidin exhibits different roles in Escherichia coli and Salmonella infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00763-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, L.; Maisetta, G.; Batoni, G.; Tavanti, A. Insights into the antimicrobial properties of hepcidins: Advantages and drawbacks as potential therapeutic agents. Molecules 2015, 20, 6319–6341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.Q.; Shen, C.B.; Luan, N.; Yao, H.M.; Long, C.B.; Lai, R.; Yan, X.W. In vivo antimalarial activity of synthetic hepcidin against Plasmodium berghei in mice. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2017, 15, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Ward, C.; Aono, S.; Lan, L.; Dykstra, C.; Kemppainen, R.J.; Morrison, E.E.; Shi, J. Comparative analysis of Xenopus tropicalis hepcidin I and hepcidin II genes. Gene 2008, 426, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, X.P.; Yi, G.; Wang, K.Y.; OuYang, P.; Chen, F.; Huang, X.L.; Huang, C.; Lai, W.M.; Zhong, Z.J.; Huo, C.L.; et al. Elizabethkingia miricola infection in Chinese spiny frog (Quasipaa spinosa). Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 1049–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Zheng, R.; Zhang, J.; Shen, B.; Dong, B. Genetic polymorphism of major histocompatibility complex class IIB alleles and pathogen resistance in the giant spiny frog Quasipaa spinosa. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014, 28, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tao, Y.H.; Chen, J.; Lu, C.P.; Zhang, L.; Lin, Z.H. Transcriptomic analysis of liver immune response in Chinese spiny frog (Quasipaa spinosa) infected with Proteus mirabilis. Open Life Sci. 2024, 19, 20221003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.C.; Cheng, X.Y.; Tao, Y.H.; Mao, Y.S.; Lu, C.P.; Lin, Z.H.; Chen, J. Assessment of the antimicrobial and immunomodulatory activity of QS-CATH, a promising therapeutic agent isolated from the Chinese spiny frogs (Quasipaa spinosa). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 283, 109425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Han, M.; Gong, J.; Ma, H.; Hao, Y.; Fang, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Jiang, W. Transcriptomic analysis of spleen-derived macrophages in response to lipopolysaccharide shows dependency on the MyD88-independent pathway in Chinese giant salamanders (Andrias davidianus). BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, C.Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Seah, R.W.X.; Ma, L.; Ding, G.H. Discovery of Ll-CATH: A novel cathelicidin from the Chong’an moustache toad (Leptobrachium liui) with antibacterial and immunomodulatory activity. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Peng, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H. Structural characteristics and immunopotentiation activity of two polysaccharides from the petal of Crocus sativus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 180, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Lv, Y.P.; Dai, Q.M.; Hu, Z.H.; Liu, Z.M.; Li, J.H. Host defense peptide LEAP-2 contributes to monocyte/macrophage polarization in barbel steed (Hemibarbus labeo). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 87, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, C.A.; Guzmán, F.; Cárdenas, C.; Marshall, S.H.; Mercado, L. Antimicrobial activity of trout hepcidin. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014, 41, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Nie, L.; Chen, J. Mudskipper (Boleophthalmus pectinirostris) hepcidin-1 and hepcidin-2 present different gene expression profile and antibacterial activity and possess distinct protective effect against Edwardsiella tarda infection. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2018, 10, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, J.V.; Caldas, C.; Vieira, I.; Ramos, M.F.; Rodrigues, P.N.S. Multiple hepcidins in a teleost fish, Dicentrarchus labrax: Different hepcidins for different roles. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 2696–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Huang, T.; Gu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, Z.; Zhao, C.; Wang, B. Characterization, expression, and functional analysis of the hepcidin gene from Brachymystax lenok. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2018, 89, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogden, K.A. Antimicrobial peptides: Pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, J.D.; Hancock, R.E. Alternative mechanisms of action of cationic antimicrobial peptides on bacteria. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2007, 5, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chi, H.; Dalmo, R.A.; Tang, X.; Xing, J.; Sheng, X.; Zhan, W. Anti-microbial activity and immunomodulation of recombinant hepcidin 2 and NK-lysin from flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, A.P.; Brodsky, I.E.; Rahner, C.; Woo, D.K.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Tempst, P.; Walsh, M.C.; Choi, Y.; Shadel, G.S.; Ghosh, S. TLR signalling augments macrophage bactericidal activity through mitochondrial ROS. Nature 2011, 472, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barroso, C.; Carvalho, P.; Nunes, M.; Gonçalves, J.F.M.; Rodrigues, P.N.S.; Neves, J.V. The era of antimicrobial peptides: Use of hepcidins to prevent or treat bacterial infections and iron disorders. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 754437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez, C.A.; Acosta, F.; Montero, D.; Guzmán, F.; Torres, E.; Vega, B.; Mercado, L. Synthetic hepcidin from fish: Uptake and protection against Vibrio anguillarum in sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 55, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Zhou, J.; Qu, Z.; Zou, Q.; Liu, X.; Su, J.; Fu, X.; Yuan, G. Administration of dietary recombinant hepcidin on grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) against Flavobacterium columnare infection under cage aquaculture conditions. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 99, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, D.; Yan, Y.; Pei, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Kong, X. Characterization of hepcidin gene and protection of recombinant hepcidin supplemented in feed against Aeromonas hydrophila infection in Yellow River carp (Cyprinus carpio haematopterus). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2023, 139, 108872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, C.H.; Pan, C.Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Lin, Y.C.; Chen, T.Y.; Rajanbabu, V.; Chen, J.Y. Impact of tilapia hepcidin 2-3 dietary supplementation on the gut microbiota profile and immunomodulation in the grouper (Epinephelus lanceolatus). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Feng, M.; Zhang, W.; Kuang, R.; Zou, Q.; Su, J.; Yuan, G. Oral administration of hepcidin and chitosan benefits growth, immunity, and gut microbiota in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1075128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masso-Silva, J.A.; Diamond, G. Antimicrobial peptides from fish. Pharmaceuticals 2014, 7, 265–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangoni, M.L.; Casciaro, B. Development of antimicrobial peptides from amphibians. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Hepcidin | Hep-t(+) | ATCCTCATCCTCTCCCTGGT |

| Hep-t(−) | GATGGAAAGGACGGAATGGC | |

| 18S rRNA | 18S rRNA-t(+) | TTAGAGGGACAAGTGGCGTT |

| 18S rRNA-t(−) | TGCAATCCCCGATCCCTATC |

| Bacteria | Isolate/Strain | MIC (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus warneri | ATCC49454 | 3.125 |

| Shigella flexneri | ATCC12022 | 25 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | ATCC6538 | 50 |

| Elizabethkingia miricola | ATCC33958 | 25 |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | ATCC7966 | - |

| Proteus mirabilis | ATCC25933 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qiao, F.; Qian, X.-Y.; Feng, Y.-K.; Chen, J. Hepcidin from the Chinese Spiny Frog (Quasipaa spinosa) Integrates Membrane-Disruptive Antibacterial Activity with Macrophage-Mediated Protection Against Elizabethkingia miricola. Genes 2025, 16, 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121450

Qiao F, Qian X-Y, Feng Y-K, Chen J. Hepcidin from the Chinese Spiny Frog (Quasipaa spinosa) Integrates Membrane-Disruptive Antibacterial Activity with Macrophage-Mediated Protection Against Elizabethkingia miricola. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121450

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiao, Fen, Xin-Yi Qian, Yi-Kai Feng, and Jie Chen. 2025. "Hepcidin from the Chinese Spiny Frog (Quasipaa spinosa) Integrates Membrane-Disruptive Antibacterial Activity with Macrophage-Mediated Protection Against Elizabethkingia miricola" Genes 16, no. 12: 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121450

APA StyleQiao, F., Qian, X.-Y., Feng, Y.-K., & Chen, J. (2025). Hepcidin from the Chinese Spiny Frog (Quasipaa spinosa) Integrates Membrane-Disruptive Antibacterial Activity with Macrophage-Mediated Protection Against Elizabethkingia miricola. Genes, 16(12), 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121450