The Utility of Genome-Wide Association Studies in Inherited Arrhythmias and Cardiomyopathies

Abstract

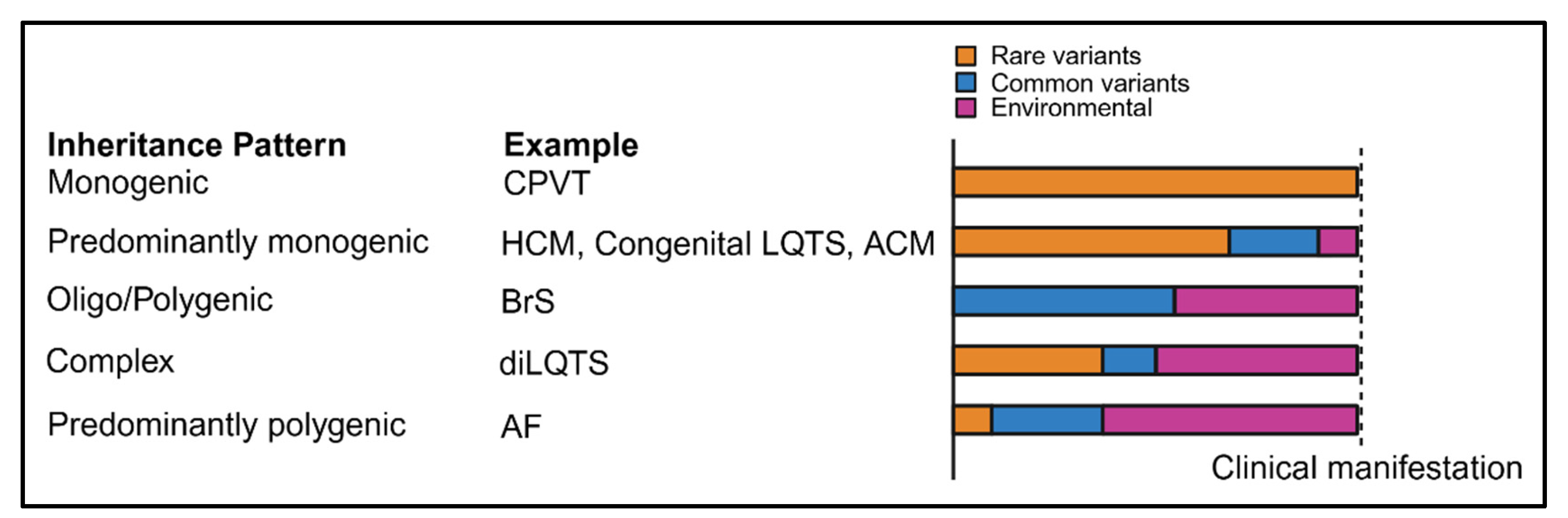

1. Introduction

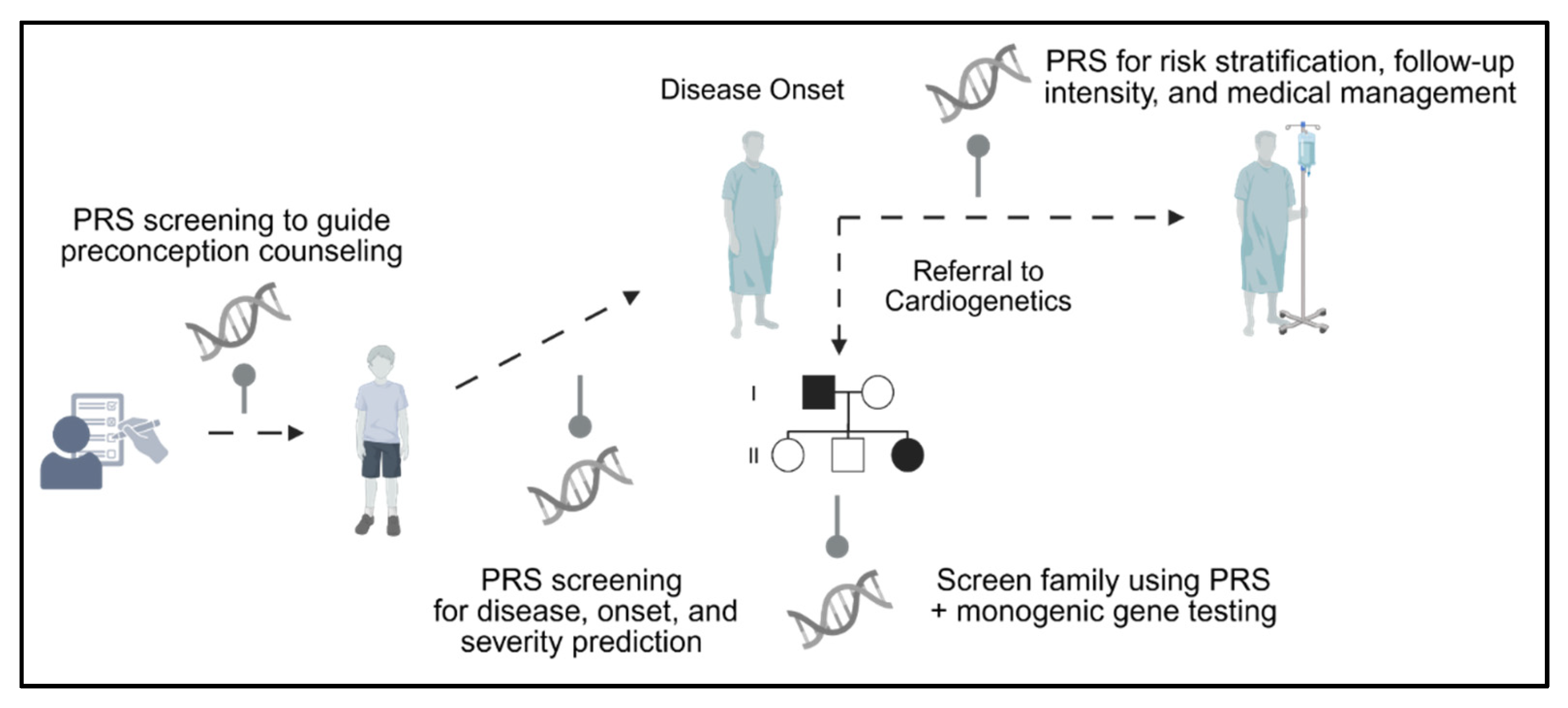

2. A Primer on GWAS

3. Polygenic Risk Scores—Derivation, Application, and Utility

4. Applications of GWAS in Inherited Arrhythmias and Cardiomyopathies

4.1. HCM

4.1.1. Novel Insights from GWAS

4.1.2. Polygenic Risk Scores

4.2. DCM

4.2.1. Novel Insights from GWAS

4.2.2. Polygenic Risk Scores

| Study (y) | Discovery (n) | Validation/Test Dataset (n) | Participant Ancestry | PRS | SNPs in PRS | PRS HR/OR (95% Cl), Including Variables Adjusted for | AUC/C Statistic (95% Cl): Clinical Risk Tool or PRS Alone vs. PRS + Clinical Risk Tool | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ning et al. (2023) [59] | 42,194 | 439,981 | European | 12 LVRWT parameters | 6345 | HRES-IS 1.69 (95% CI = 1.33–2.15), no variables adjusted for reported. | C statistic 0.67 for clinical risk model (no 95% CIs reported) | PRSs derived from LVRWT traits are associated with incident HCM. |

| C statistic range of 0.67–0.69 for PRS + clinical risk model (no 95% CIs reported) | ||||||||

| Harper et al. (2021) [60] | 50,266 | GeL—35,935 RBH—1570 Netherlands—3092 | Mixed-ancestry | HCM | 27 | OR per SD 1.73 (95% CI 1.63–1.83), adjusted for first ten principal components, age and gender. | N/A | The PRS predicts the odds of HCM and was associated with greater LV wall thickness in sarcomere variant carriers in a validation meta-analysis of three independent HCM cohorts. |

| Biddinger et al. (2022) [61] | Used Harper et al. (2021) study | UKB—184,511 MGB—30,716 | Largely European (Mixed-ancestry) | HCM | 27 | HR per SD 1.18 (95% CI, 1.12–1.24), adjusted for age, sex, genotyping array, and PCs 1–5. | AUC 0.670 (95% CI 0.635–0.705) for age, sex, and PCs 1–5 | The PRS was associated with increased odds of HCM in the general population. |

| AUC 0.706 (95% CI 0.669–0.742) for PRS + co-variates | ||||||||

| Zheng et al. (2025) [62] | HCM GWAS—74,259 Multi-trait GWAS—36,083 Multi-trait | UKB—376,730 (EUR) + 16,349 (non-EUR) GeL—683 EMC—214 RBH—440 | Largely European (Mixed-ancestry) | HCM + Multitrait (LVconc, LVESV, straincirc) | PGSGWAS = 376,730 SNP predictors PGSMTAG = 374,113 SNP predictors | GWAS: 1.97 OR per SD (95% CI 1.81–2.15) MTAG: OR per SD 2.34 (95% CI 2.12–2.59), adjusted for age, age2, sex and first ten genetic PCs. | N/A | The PRS predicted HCM risk in the general population, penetrance in rare variant carriers, and adverse cardiovascular outcomes (including death) in diagnosed patients, and correlated with imaging features typical of HCM. |

| Aung et al. (2019) [71] | 16,923 | 4383 | European | LVEDV LVESV LVEF LVMVR LVSV LVM | Not specified | LVEDV → HR 1.18 (95% CI 1.03–1.36) LVESV → HR 1.32 (95% CI 1.15–1.51) LVEF → HR 0.79 (95% CI 0.69–0.90) LVMVR → HR 0.76 (0.66–0.88) Models adjusted for age, sex, BMI, SBP and DBP corrected for anti-hypertensive medication use, smoking status, regular alcohol use, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and first 15 genetic PCs. | N/A | PRSs for LVEDV, LVESV, LVEF, and LVMVR significantly predicted heart failure after adjustment for age, sex, body size, and standard cardiovascular risk factors, confirming they were independent predictors. |

| Pirruccello et al. (2020) [72] | 36,041 | MESA—2184 BBJ—19,000 | Discovery: European Validation: Multi-ancestry | LVEDV LVEDVi LVESV LVESVi LVEF SV SVi | 28 (LVESVi) | HR per SD 1.58 (95% CI 1.43–1.76), adjusted for sex, genotyping array, the first five PCs, and the cubic basis spline of age at enrollment. | N/A | The PRS for LVESVi significantly predicted future DCM events, indicating that higher genetically mediated LVESVi was linked to a higher DCM risk. |

| Pirruccello et al. (2022) [73] | 41,135 | UKB—359,899 MGB—23,386 BBJ—154,450 | European | RV Parampara RA measurements PA measurements | 1,117,425 | HR per SD 1.33 (95% CI not reported), adjusted for covariates including sex, the cubic basis spline of age at enrollment, the interaction between the cubic basis spline of age at enrollment and sex, the genotyping array, the first five PCs of ancestry and the cubic basis splines of height (cm), weight (kg), body mass index (BMI) (kg·m–2), diastolic blood pressure, and systolic blood pressure. | N/A | The most significant PRS was for right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF), which strongly and independently predicted incident DCM. |

| Garnier et al. (2021) [74] | 7159 | 1547 | European | DCM | 4 | OR per SD 3.34 (95% CI 1.87–6.00) for patients with 8 risk alleles OR per SD 0.21 (95% CI 0.06–0.77) for patients with 1 risk allele. | N/A | The PRS showed a clear association with DCM risk: individuals with eight risk alleles had about a 3-fold increased risk, while those with one risk allele had a 5-fold decreased risk compared to the median group. |

| Jurgens et al. (2024) [66] | 955,733 | 1,448,963 | European, African, and Admixed-American ancestries | DCM | DCM: 1,068,761 –1,098,677 MTAG-DCM: 1,038,394–1,075,760 | DCM trait PRS: OR per SD 1.93 (95% CI 1.79–2.07) MTAG PRS: OR per SD 1.73 (95% CI 1.61–1.86) | GWAS DCM AUC 0.64 (95% CI 0.62–0.66) for PRS w/o covariates MTAG-DCM AUC 0.67 (95% CI 0.65–0.68) for PRS w/o covariates | The PRSs significantly predicted DCM across European, African, and Admixed-American ancestries and were independent predictors of systolic heart failure (HF) in multiple contexts. |

| GWAS DCM AUC 0.71 (95% CI 0.69–0.73) for PRS w/covariates MTAG-DCM AUC 0.73 (95% CI 0.71–0.75) for PRS w/covariates |

4.3. BrS

4.3.1. Novel Insights from GWAS

4.3.2. Polygenic Risk Scores

4.4. LQTS

4.4.1. Novel Insights from GWAS

4.4.2. Polygenic Risk Scores

| Authors (y) | Discovery (n) | Validation/Test Dataset (n) | Participant Ancestry | PRS | SNPs in PRS | PRS HR/OR (95% Cl), Including Variables Adjusted for | AUC/C Statistic (95% Cl): Clinical Risk Tool or PRS Alone vs. PRS + Clinical Risk Tool | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tadros et al. (2019) [80] | 1368 | N/A | European | PR interval (PRSPR) QRS duration (PRSQRS) Brugada syndrome (PRSBrS) | PRSPR: 44 PRSQRS: 26 PRSBrS: 3 | PRSBrS OR per SD 1.14 (95% CI 1.10–1.18), full ancestry cohort PRSBrS OR per SD 1.16 (95% CI 1.12–1.20), when excluding SCN5A variant carriers | C statistic 0.68 for PRSBrS (95% CI 0.65–0.71) | PRSBrS, alongside baseline QRS, Type II/III BrS pattern, and family history of BrS, independently predicted ajmaline-induced Type I BrS ECG. |

| C statistic 0.74 for PRSBrS + Family history for BrS and Baseline ECG data (95% CI 0.71–0.77) | ||||||||

| Wijeyeratne et al. (2020) [23] | Tadros et al. (2019) study | 312 | Mixed ancestry | BrS | 3 SNPs, 6 high-risk alleles | OR per risk allele 1.46 (95% CI 1.11–1.94) OR for BrS ≥ 4 risk alleles 4.15 (95% CI 1.45–11.85) for BrS phenotype | N/A | The PRS predicted the presence of spontaneous or drug-induced type 1 ECG pattern (i.e., BrS phenotype) in both SCN5A mutation carriers and genotype-negative relatives. |

| Barc et al. (2022) [77] | 12,821 | N/A | European | BrS | 21 | OR per SD 1.16 (95% CI 1.10–1.21) for atrioventricular conduction disorders | N/A | The PRS better predicted BrS diagnosis in SCN5A genotype-negative individuals compared to genotype-positive individuals, and better predicted spontaneous Type I BrS ECG compared to drug-induced Type I BrS ECG. |

| Ishikawa et al. (2024) [81] | Japanese cohort = 2574 Meta analysis Japanese and European GWAS = 15,395 | N/A | Japanese and European | BrS | 17 | OR per SD 2.12 (95% CI 1.94–2.31) risk of BrS in the Japanese cohort | N/A | The PRS strongly and independently predicted BrS presence, but did not predict lethal arrhythmic events. |

| Strauss et al. (2017) [87] | 22 | 987 | Mixed-Ancestry | QT | 61 | N/A | N/A | The PRS was correlated with drug-induced QTc prolongation and was a significant predictor of drug-induced Torsade de Pointes in an independent validation sample. |

| Turkowski et al. (2020) [88] | N/A | 423 | European | QTc | 61 | N/A | N/A | The PRS predicted higher QTc values in probands and those with prolonged QTc, but did not predict symptomatic status or serious arrhythmic events. |

| Nauffal et al. (2022) [89] | 84,630 | TOPMed— 26,976 | European | QTc | 1,110,494 | Mean QTc change per decile of PRS: 1.4 ms (95% CI 1.3–1.5) | N/A | The PRS showed a significant, independent association with QTc duration: each decile increase in PRS corresponded to a 1.4 ms QTc prolongation, and individuals in the top decile had an average 8.7 ms longer QTc, similar to the effect of monogenic rare variants. |

| Lancaster et al. (2024) [90] | 978 | N/A | European | QTc | 465,399 | OR per one-SD increase: 1.10 (95% CI 1.05–1.16) | AUC 0.74 (95% CI 0.62–0.87) | The PRS predicted both the magnitude of ΔQTc and the likelihood of extreme response, but not post-sotalol QTc > 500 ms. |

| Simon et al. (2024) [92] | - | 2500 | Discovery: European Test: Mixed-ancestry | QTc | Not specified | OR per SD: 1.34 (95% CI 1.17–1.53), adjusted model with age, AF, HF, and high-risk medications | AUC for clinical risk tool 0.729 (no 95% CI reported) | The PRS was an independent predictor of diLQTS after exposure to known QT-prolonging drugs. It was an independent predictor after adjusting for age, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and high-risk medications. |

| AUC for clinical risk tool + PRS 0.751 (no 95% CI reported) | ||||||||

| Lahrouchi et al. (2020) [83] | 11,546 | N/A | European and Japanese | QT | 68 | OR per SD increase EUR: 1.38 (95% CI 1.30–1.47) JAP: 1.51 (95% CI 1.36–1.67) Meta-analysis:1.41 (95% CI 1.34–1.48) | N/A | The PRS was an independent predictor of LQTS susceptibility in both European and Japanese cohorts and was notably higher in genotype-negative than genotype-positive patients, but it did not independently predict QTc duration in multivariable models or LAE occurrence. |

| Lopez-Medina et al. (2025) [91] | Used Strauss et al. (2017) study | 6970 | Mixed-ancestry (self-reported White, African American, and Asian) | QT | 61 | OR for White patients per SD 1.44 (95% CI 1.09–1.89), adjusted for propensity score OR did not reach statistical significance for African American (OR 2.18, 95% CI 0.98–5.49) and Asian (OR 3.21, 95% CI 0.69–16.87) cohorts | N/A | The PRS significantly predicted marked QTc prolongation with high-risk drug use in self-reported White patients, with suggestive but non-significant associations in African American and Asian groups, likely due to smaller sample sizes. |

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Offerhaus, J.A.; Bezzina, C.R.; Wilde, A.A.M. Epidemiology of inherited arrhythmias. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, W.J.; Judge, D.P. Epidemiology of the inherited cardiomyopathies. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingles, J. Psychological issues in managing families with inherited cardiovascular diseases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2020, 10, a036558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dababneh, S.; Roston, T.M. Evolution of the management of ultrarare inherited arrhythmias and cardiomyopathies. Future Cardiol. 2025, 2110, 731–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, M. Linkage analysis and long QT syndrome. Using genetics to study cardiovascular disease. Circulation 1992, 85, 1973–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, M.E.; Splawski, I.; Timothy, K.W.; Vincent, G.M.; Green, E.D.; Keating, M.T. A molecular basis for cardiac arrhythmia: HERG mutations cause long QT syndrome. Cell 1995, 80, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shen, J.; Splawski, I.; Atkinson, D.; Li, Z.; Robinson, J.L.; Moss, A.J.; Towbin, J.A.; Keating, M.T. SCN5A Mutations Associated with an Inherited Cardiac Arrhythmia, Long QT Syndrome. Cell 1995, 80, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Curran, M.E.; Splawski, I.; Burn, T.C.; Millholland, J.M.; VanRaay, T.J.; Shen, J.; Timothy, K.W.; Vincent, G.M.; de Jager, T.; et al. Positional cloning of a novel potassium channel gene: KVLQT1 mutations cause cardiac arrhythmias. Nat. Genet. 1996, 12, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Kirsch, G.E.; Zhang, D.; Brugada, R.; Brugada, J.; Brugada, P.; Potenza, D.; Moya, A.; Borggrefe, M.; Breithardt, G.; et al. Genetic basis and molecular mechanism for idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Nature 1998, 392, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisterfer-Lowrance, A.A.; Kass, S.; Tanigawa, G.; Vosberg, H.P.; McKenna, W.; Seidman, C.E.; Seidman, J.G. A molecular basis for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A beta cardiac myosin heavy chain gene missense mutation. Cell 1990, 62, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier, L.; Bonne, G.; Bährend, E.; Yu, B.; Richard, P.; Niel, F.; Hainque, B.; Cruaud, C.; Gary, F.; Labeit, S.; et al. Organization and sequence of human cardiac myosin binding protein C gene (MYBPC3) and identification of mutations predicted to produce truncated proteins in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 1997, 80, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerull, B.; Heuser, A.; Wichter, T.; Paul, M.; Basson, C.T.; McDermott, D.A.; Lerman, B.B.; Markowitz, S.M.; Ellinor, P.T.; MacRae, C.A.; et al. Mutations in the desmosomal protein plakophilin-2 are common in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Nat. Genet. 2004, 36, 1162–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerull, B.; Brodehl, A. Insights Into Genetics and Pathophysiology of Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2021, 18, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, L.R.; Ho, C.Y.; Elliott, P.M. Genetics of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Established and emerging implications for clinical practice. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 2727–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, B.; Behr, E.R. New Insights into the Genetic Basis of Inherited Arrhythmia Syndromes. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2016, 9, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grondin, S.; Neveu, B.; Soltani, I.; Alaoui, A.A.; Messina, A.; Gaumond, L.; Demonière, F.; Lo, K.S.; Jeuken, A.; Barahona-Dussault, C.; et al. Clinical Effect of Genetic Testing in Inherited Cardiovascular Diseases: A 14-Year Retrospective Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 85, 988–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musunuru, K.; Hershberger, R.E.; Day, S.M.; Klinedinst, N.J.; Landstrom, A.P.; Parikh, V.N.; Prakash, S.; Semsarian, C.; Sturm, A.C.; American Heart Association Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine; et al. Genetic Testing for Inherited Cardiovascular Diseases: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2020, 13, E000067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunwald, E.; Saberi, S.; Abraham, T.P.; Elliott, P.M.; Olivotto, I. Mavacamten: A first-in-class myosin inhibitor for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 4622–4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, N.; Li, D.; Rieder, M.J.; Siegfried, J.D.; Rampersaud, E.; Züchner, S.; Mangos, S.; Gonzalez-Quintana, J.; Wang, L.; McGee, S.; et al. Genome-wide studies of copy number variation and exome sequencing identify rare variants in BAG3 as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 88, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, F.; Gigli, M.; Graw, S.L.; Judge, D.P.; Merlo, M.; Murray, B.; Calkins, H.; Sinagra, G.; Taylor, M.R.; Mestroni, L.; et al. FLNC truncations cause arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J. Med. Genet. 2020, 57, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merner, N.D.; Hodgkinson, K.A.; Haywood, A.F.; Connors, S.; French, V.M.; Drenckhahn, J.D.; Kupprion, C.; Ramadanova, K.; Thierfelder, L.; McKenna, W.; et al. Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy Type 5 Is a Fully Penetrant, Lethal Arrhythmic Disorder Caused by a Missense Mutation in the TMEM43 Gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 82, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butters, A.; Bagnall, R.D.; Ingles, J. Revisiting the Diagnostic Yield of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Genetic Testing. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2020, 13, E002930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijeyeratne, Y.D.; Tanck, M.W.; Mizusawa, Y.; Batchvarov, V.; Barc, J.; Crotti, L.; Bos, J.M.; Tester, D.J.; Muir, A.; Veltmann, C.; et al. SCN5A Mutation Type and a Genetic Risk Score Associate Variably with Brugada Syndrome Phenotype in SCN5A Families. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2020, 13, E002911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggerty, C.M.; Damrauer, S.M.; Levin, M.G.; Birtwell, D.; Carey, D.J.; Golden, A.M.; Hartzel, D.N.; Hu, Y.; Judy, R.; Kelly, M.A.; et al. Genomics-First Evaluation of Heart Disease Associated with Titin-Truncating Variants. Circulation 2019, 140, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinrinade, O.; Koskenvuo, J.W.; Alastalo, T.P. Prevalence of titin truncating variants in general population. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustetto, C.; Nangeroni, G.; Cerrato, N.; Rudic, B.; Tülümen, E.; Gribaudo, E.; Giachino, D.F.; Barbonaglia, L.; Biava, L.M.; Carvalho, P.; et al. Ventricular conduction delay as marker of risk in Brugada Syndrome. Results from the analysis of clinical and electrocardiographic features of a large cohort of patients. Int. J. Cardiol. 2020, 302, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrone, M.; Remme, C.A.; Tadros, R.; Bezzina, C.R.; Delmar, M. Beyond the one gene-one disease paradigm complex genetics and pleiotropy in inheritable cardiac disorders. Circulation 2019, 140, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, R.; Jurgens, S.J.; Erdmann, J.; Bezzina, C.R. Genome-Wide Association Studies of Cardiovascular Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2023, 103, 2039–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.; Patel, N.; Turcotte, M.; Bossé, Y.; Paré, G.; Meyre, D. Benefits and limitations of genome-wide association studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, T.; Song, L.; Guo, Y.; Chen, C.; Yang, J. From genetic associations to genes: Methods, applications, and challenges. Trends Genet. 2024, 40, 642–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marees, A.T.; de Kluiver, H.; Stringer, S.; Vorspan, F.; Curis, E.; Marie-Claire, C.; Derks, E.M. A tutorial on conducting genome-wide association studies: Quality control and statistical analysis. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 27, e1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, C.A.; Mooij, J.M.; Heskes, T.; Posthuma, D. MAGMA: Generalized Gene-Set Analysis of GWAS Data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015, 11, e1004219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Wang, K.; Wei, P.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Tan, K.; Boerwinkle, E.; Potash, J.B.; Han, S. FLAGS: A flexible and adaptive association test for gene sets using summary statistics. Genetics 2016, 202, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mai, J.; Lu, M.; Gao, Q.; Zeng, J.; Xiao, J. Transcriptome-wide association studies: Recent advances in methods, applications and available databases. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuber, V.; Grinberg, N.F.; Gill, D.; Manipur, I.; Slob, E.A.W.; Patel, A.; Wallace, C.; Burgess, S. Combining evidence from Mendelian randomization and colocalization: Review and comparison of approaches. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 109, 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartzentruber, J.; Cooper, S.; Liu, J.Z.; Barrio-Hernandez, I.; Bello, E.; Kumasaka, N.; Young, A.M.H.; Franklin, R.J.M.; Johnson, T.; Estrada, K.; et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis, fine-mapping and integrative prioritization implicate new Alzheimer’s disease risk genes. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, A.O.; Koca, D. The effects of case/control ratio and sample size on genome-wide association studies: A simulation study. Vet. Med. Sci. 2024, 10, e1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, E.P.; Park, J.W. Sample Size and Statistical Power Calculation in Genetic Association Studies. Genom. Inform. 2012, 10, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Wang, X.; Carr, M.; Kim, A.; Gazal, S.; Mohammadi, P.; Wu, L.; Pirruccello, J.; Kachuri, L.; Gusev, A.; et al. Improved multiancestry fine-mapping identifies cis-regulatory variants underlying molecular traits and disease risk. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 1881–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramarenko, D.R.; Jurgens, S.J.; Pinto, Y.M.; Bezzina, C.R.; Amin, A.S. Polygenic Risk Scores in Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Towards the Future. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2025, 27, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glinge, C.; Lahrouchi, N.; Jabbari, R.; Tfelt-Hansen, J.; Bezzina, C.R. Genome-wide association studies of cardiac electrical phenotypes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 1620–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minikel, E.V.; Painter, J.L.; Dong, C.C.; Nelson, M.R. Refining the impact of genetic evidence on clinical success. Nature 2024, 629, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dababneh, S.F.; Babini, H.; Jiménez-Sábado, V.; Teves, S.S.; Kim, K.H.; Tibbits, G.F. Dissecting cardiovascular disease-associated noncoding genetic variants using human iPSC models. Stem Cell Rep. 2025, 20, 102467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heshmatzad, K.; Naderi, N.; Maleki, M.; Abbasi, S.; Ghasemi, S.; Ashrafi, N.; Fazelifar, A.F.; Mahdavi, M.; Kalayinia, S. Role of non-coding variants in cardiovascular disease. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2023, 27, 1621–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.W.; Mak, T.S.H.; O’Reilly, P.F. Tutorial: A guide to performing polygenic risk score analyses. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 2759–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phulka, J.S.; Ashraf, M.; Bajwa, B.K.; Pare, G.; Laksman, Z. Current State and Future of Polygenic Risk Scores in Cardiometabolic Disease: A Scoping Review. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2023, 16, 286–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachuri, L.; Chatterjee, N.; Hirbo, J.; Schaid, D.J.; Martin, I.; Kullo, I.J.; Kenny, E.E.; Pasaniuc, B.; Polygenic Risk Methods in Diverse Populations (PRIMED) Consortium Methods Working Group; Witte, J.S.; et al. Principles and methods for transferring polygenic risk scores across global populations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2024, 25, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.; Lin, Y.F.; Feng, Y.A.; Chen, C.Y.; Lam, M.; Guo, Z.; Stanley Global Asia Initiatives; He, L.; Sawa, A.; Martin, A.R.; et al. Improving polygenic prediction in ancestrally diverse populations. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhan, J.; Jin, J.; Zhang, J.; Lu, W.; Zhao, R.; Ahearn, T.U.; Yu, Z.; O’Connell, J.; Jiang, Y.; et al. A new method for multiancestry polygenic prediction improves performance across diverse populations. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 1757–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.L.; Tcheandjieu, C.; Dikilitas, O.; Iyer, K.; Miyazawa, K.; Hilliard, A.; Lynch, J.; Rotter, J.I.; Chen, Y.I.; Sheu, W.H.; et al. Multi-Ancestry Polygenic Risk Score for Coronary Heart Disease Based on an Ancestrally Diverse Genome-Wide Association Study and Population-Specific Optimization. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2024, 17, e004272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunkert, H.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Inouye, M.; Patel, R.S.; Ripatti, S.; Widen, E.; Sanderson, S.C.; Kaski, J.P.; McEvoy, J.W.; Vardas, P.; et al. Clinical utility and implementation of polygenic risk scores for predicting cardiovascular disease A clinical consensus statement of the ESC Council on Cardiovascular Genomics, the ESC Cardiovascular Risk Collaboration, and the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 1372–1383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, J.W.; Raghavan, S.; Marquez-Luna, C.; Luzum, J.A.; Damrauer, S.M.; Ashley, E.A.; O’Donnell, C.J.; Willer, C.J.; Natarajan, P.; American Heart Association Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine; et al. Polygenic Risk Scores for Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 146, E93–E118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Li, W.; Macheret, F.; Gabriel, R.A.; Ohno-Machado, L. A tutorial on calibration measurements and calibration models for clinical prediction models. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2021, 27, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wand, H.; Lambert, S.A.; Tamburro, C.; Iacocca, M.A.; O’Sullivan, J.W.; Sillari, C.; Kullo, I.J.; Rowley, R.; Dron, J.S.; Brockman, D.; et al. Improving reporting standards for polygenic scores in risk prediction studies. Nature 2021, 591, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunwald, E. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 393, 1004–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topriceanu, C.C.; Pereira, A.C.; Moon, J.C.; Captur, G.; Ho, C.Y. Meta-Analysis of Penetrance and Systematic Review on Transition to Disease in Genetic Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2024, 149, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, R.; Francis, C.; Xu, X.; Vermeer, A.M.C.; Harper, A.R.; Huurman, R.; Kelu Bisabu, K.; Walsh, R.; Hoorntje, E.T.; Te Rijdt, W.P.; et al. Shared genetic pathways contribute to risk of hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies with opposite directions of effect. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, R.; Zheng, S.L.; Grace, C.; Jordà, P.; Francis, C.; West, D.M.; Jurgens, S.J.; Thomson, K.L.; Harper, A.R.; Ormondroyd, E.; et al. Large-scale genome-wide association analyses identify novel genetic loci and mechanisms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.; Fan, L.; Jin, M.; Wang, W.; Hu, Z.; Cai, Y.; Chen, L.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Chen, C.; et al. Genome-wide association analysis of left ventricular imaging-derived phenotypes identifies 72 risk loci and yields genetic insights into hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, A.R.; Goel, A.; Grace, C.; Thomson, K.L.; Petersen, S.E.; Xu, X.; Waring, A.; Ormondroyd, E.; Kramer, C.M.; Ho, C.Y.; et al. Common genetic variants and modifiable risk factors underpin hypertrophic cardiomyopathy susceptibility and expressivity. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddinger, K.J.; Jurgens, S.J.; Maamari, D.; Gaziano, L.; Choi, S.H.; Morrill, V.N.; Halford, J.L.; Khera, A.V.; Lubitz, S.A.; Ellinor, P.T.; et al. Rare and Common Genetic Variation Underlying the Risk of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in a National Biobank. JAMA Cardiol. 2022, 7, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.L.; Jurgens, S.J.; McGurk, K.A.; Xu, X.; Grace, C.; Theotokis, P.I.; Buchan, R.J.; Francis, C.; de Marvao, A.; Curran, L.; et al. Evaluation of polygenic scores for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the general population and across clinical settings. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, R.G.; Semsarian, C.; Macdonald, P. Dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet 2017, 390, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villard, E.; Perret, C.; Gary, F.; Proust, C.; Dilanian, G.; Hengstenberg, C.; Ruppert, V.; Arbustini, E.; Wichter, T.; Germain, M.; et al. A genome-wide association study identifies two loci associated with heart failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meder, B.; Rühle, F.; Weis, T.; Homuth, G.; Keller, A.; Franke, J.; Peil, B.; Lorenzo Bermejo, J.; Frese, K.; Huge, A.; et al. A genome-wide association study identifies 6p21 as novel risk locus for dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgens, S.J.; Rämö, J.T.; Kramarenko, D.R.; Wijdeveld, L.F.J.M.; Haas, J.; Chaffin, M.D.; Garnier, S.; Gaziano, L.; Weng, L.C.; Lipov, A.; et al. Genome-wide association study reveals mechanisms underlying dilated cardiomyopathy and myocardial resilience. Nat. Genet. 2024, 56, 2636–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, F.; Cuenca, S.; Bilińska, Z.; Toro, R.; Villard, E.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Ochoa, J.P.; Asselbergs, F.; Sammani, A.; Franaszczyk, M.; et al. Dilated Cardiomyopathy Due to BLC2-Associated Athanogene 3 (BAG3) Mutations. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2471–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Levin, M.G.; Zhang, D.; Reza, N.; Mead, J.O.; Carruth, E.D.; Kelly, M.A.; Winters, A.; Kripke, C.M.; Judy, R.L.; et al. Bidirectional Risk Modulator and Modifier Variant of Dilated and Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in BAG. JAMA Cardiol. 2024, 9, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Mu, Y.; Bogomolovas, J.; Fang, X.; Veevers, J.; Nowak, R.B.; Pappas, C.T.; Gregorio, C.C.; Evans, S.M.; Fowler, V.M.; et al. HSPB7 is indispensable for heart development by modulating actin filament assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11956–11961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teerlink, J.R.; Diaz, R.; Felker, G.M.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Metra, M.; Solomon, S.D.; Adams, K.F.; Anand, I.; Arias-Mendoza, A.; Biering-Sørensen, T.; et al. Cardiac Myosin Activation with Omecamtiv Mecarbil in Systolic Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, N.; Vargas, J.D.; Yang, C.; Cabrera, C.P.; Warren, H.R.; Fung, K.; Tzanis, E.; Barnes, M.R.; Rotter, J.I.; Taylor, K.D.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of left ventricular image-derived phenotypes identifies fourteen loci associated with cardiac morphogenesis and heart failure development. Circulation 2019, 140, 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirruccello, J.P.; Bick, A.; Wang, M.; Chaffin, M.; Friedman, S.; Yao, J.; Guo, X.; Venkatesh, B.A.; Taylor, K.D.; Post, W.S.; et al. Analysis of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in 36,000 individuals yields genetic insights into dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirruccello, J.P.; Di Achille, P.; Nauffal, V.; Nekoui, M.; Friedman, S.F.; Klarqvist, M.D.R.; Chaffin, M.D.; Weng, L.C.; Cunningham, J.W.; Khurshid, S.; et al. Genetic analysis of right heart structure and function in 40,000 people. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 792–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnier, S.; Harakalova, M.; Weiss, S.; Mokry, M.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V.; Hengstenberg, C.; Cappola, T.P.; Isnard, R.; Arbustini, E.; Cook, S.A.; et al. Genome-wide association analysis in dilated cardiomyopathy reveals two new players in systolic heart failure on chromosomes 3p25.1 and 22q11. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 2000–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krahn, A.D.; Behr, E.R.; Hamilton, R.; Probst, V.; Laksman, Z.; Han, H.C. Brugada Syndrome. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2022, 8, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, B.; Na, J.; Monasky, M.M.; Brugada, R.; Miyasaka, Y.; Brugada, J.; Brugada, P.; Krittanawong, C. Brugada syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2025, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barc, J.; Tadros, R.; Glinge, C.; Chiang, D.Y.; Jouni, M.; Simonet, F.; Jurgens, S.J.; Baudic, M.; Nicastro, M.; Potet, F.; et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify new Brugada syndrome risk loci and highlight a new mechanism of sodium channel regulation in disease susceptibility. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, D.Y.; Verkerk, A.O.; Victorio, R.; Shneyer, B.I.; van der Vaart, B.; Jouni, M.; Narendran, N.; Kc, A.; Sampognaro, J.R.; Vetrano-Olsen, F.; et al. The Role of MAPRE2 and Microtubules in Maintaining Normal Ventricular Conduction. Circ. Res. 2024, 134, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerman, C.C.; Podliesna, S.; Tadros, R.; Lodder, E.M.; Mengarelli, I.; de Jonge, B.; Beekman, L.; Barc, J.; Wilders, R.; Wilde, A.A.M.; et al. The brugada syndrome susceptibility gene HEY2 modulates cardiac transmural ion channel patterning and electrical heterogeneity. Circ. Res. 2017, 121, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, R.; Tan, H.L.; ESCAPE-NET Investigators; El Mathari, S.; Kors, J.A.; Postema, P.G.; Lahrouchi, N.; Beekman, L.; Radivojkov-Blagojevic, M.; Amin, A.S.; et al. Predicting cardiac electrical response to sodium-channel blockade and Brugada syndrome using polygenic risk scores. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 3108–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T.; Masuda, T.; Hachiya, T.; Dina, C.; Simonet, F.; Nagata, Y.; Tanck, M.W.T.; Sonehara, K.; Glinge, C.; Tadros, R.; et al. Brugada syndrome in Japan and Europe: A genome-wide association study reveals shared genetic architecture and new risk loci. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 2333–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahn, A.D.; Laksman, Z.; Sy, R.W.; Postema, P.G.; Ackerman, M.J.; Wilde, A.A.M.; Han, H.C. Congenital Long QT Syndrome. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2022, 8, 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahrouchi, N.; Tadros, R.; Crotti, L.; Mizusawa, Y.; Postema, P.G.; Beekman, L.; Walsh, R.; Hasegawa, K.; Barc, J.; Ernsting, M.; et al. Transethnic genome-wide association study provides insights in the genetic architecture and heritability of long QT syndrome. Circulation 2020, 142, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, W.J.; Lahrouchi, N.; Isaacs, A.; Duong, T.; Foco, L.; Ahmed, F.; Brody, J.A.; Salman, R.; Noordam, R.; Benjamins, J.W.; et al. Genetic analyses of the electrocardiographic QT interval and its components identify additional loci and pathways. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronchi, C.; Bernardi, J.; Mura, M.; Stefanello, M.; Badone, B.; Rocchetti, M.; Crotti, L.; Brink, P.; Schwartz, P.J.; Gnecchi, M.; et al. NOS1AP polymorphisms reduce NOS1 activity and interact with prolonged repolarization in arrhythmogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Auer, D.; Johnson, M.; Sanchez, E.; Ross, H.; Ward, C.; Chakravarti, A.; Kapoor, A. Cardiac muscle–restricted partial loss of Nos1ap expression has limited but significant impact on electrocardiographic features. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2023, 13, jkad208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, D.G.; Vicente, J.; Johannesen, L.; Blinova, K.; Mason, J.W.; Weeke, P.; Behr, E.R.; Roden, D.M.; Woosley, R.; Kosova, G.; et al. Common genetic variant risk score is associated with drug-induced QT prolongation and torsade de pointes risk. Circulation 2017, 135, 1300–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkowski, K.L.; Dotzler, S.M.; Tester, D.J.; Giudicessi, J.R.; Bos, J.M.; Speziale, A.D.; Vollenweider, J.M.; Ackerman, M.J. Corrected QT Interval-Polygenic Risk Score and Its Contribution to Type 1, Type 2, and Type 3 Long-QT Syndrome in Probands and Genotype-Positive Family Members. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2020, 13, E002922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauffal, V.; Morrill, V.N.; Jurgens, S.J.; Choi, S.H.; Hall, A.W.; Weng, L.C.; Halford, J.L.; Austin-Tse, C.; Haggerty, C.M.; Harris, S.L.; et al. Monogenic and Polygenic Contributions to QTc Prolongation in the Population. Circulation 2022, 145, 1524–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, M.C.; Davogustto, G.; Prifti, E.; Perret, C.; Funck-Brentano, C.; Roden, D.M.; Salem, J.E. A Polygenic Predictor of Baseline QTc is Associated with Sotalol-Induced QT Prolongation. Circulation 2024, 150, 1984–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Medina, A.I.; Campos-Staffico, A.M.; Chahal, C.A.A.; Jacoby, J.P.; Volkers, I.; Berenfeld, O.; Luzum, J.A. Polygenic risk score for drug-induced long QT syndrome: Independent validation in a real-world patient cohort. Pharmacogenet Genom. 2025, 35, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, S.T.; Lin, M.; Trinkley, K.E.; Aleong, R.; Rafaels, N.; Crooks, K.R.; Reiter, M.J.; Gignoux, C.R.; Rosenberg, M.A. A polygenic risk score for the QT interval is an independent predictor of drug-induced QT prolongation. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzerova, J.; Hurta, M.; Barton, V.; Lexa, M.; Walther, D.; Provaznik, V.; Weckwerth, W. A perspective on genetic and polygenic risk scores—Advances and limitations and overview of associated tools. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbae240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corpas, M.; Pius, M.; Poburennaya, M.; Guio, H.; Dwek, M.; Nagaraj, S.; Lopez-Correa, C.; Popejoy, A.; Fatumo, S. Bridging genomics’ greatest challenge: The diversity gap. Cell Genom. 2025, 5, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellaoui, A.; Yengo, L.; Verweij, K.J.H.; Visscher, P.M. 15 years of GWAS discovery: Realizing the promise. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 110, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourlen, P.; Chapuis, J.; Lambert, J.-C. Using High-Throughput Animal or Cell-Based Models to Functionally Characterize GWAS Signals. Curr. Genet. Med. Rep. 2018, 6, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dababneh, S.; Hamledari, H.; Maaref, Y.; Jayousi, F.; Hosseini, D.B.; Khan, A.; Jannati, S.; Jabbari, K.; Arslanova, A.; Butt, M.; et al. Advances in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Disease Modelling Using hiPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Can. J. Cardiol. 2024, 40, 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busby, G.B.; Kulm, S.; Bolli, A.; Kintzle, J.; Domenico PDi Bottà, G. Ancestry-specific polygenic risk scores are risk enhancers for clinical cardiovascular disease assessments. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerga-Jaso, J.; Terpolovsky, A.; Novković, B.; Osama, A.; Manson, C.; Bohn, S.; De Marino, A.; Kunitomi, M.; Yazdi, P.G. Optimization of multi-ancestry polygenic risk score disease prediction models. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dababneh, S.; Ardehali, A.; Badesha, J.; Laksman, Z. The Utility of Genome-Wide Association Studies in Inherited Arrhythmias and Cardiomyopathies. Genes 2025, 16, 1448. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121448

Dababneh S, Ardehali A, Badesha J, Laksman Z. The Utility of Genome-Wide Association Studies in Inherited Arrhythmias and Cardiomyopathies. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1448. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121448

Chicago/Turabian StyleDababneh, Saif, Arya Ardehali, Jasleen Badesha, and Zachary Laksman. 2025. "The Utility of Genome-Wide Association Studies in Inherited Arrhythmias and Cardiomyopathies" Genes 16, no. 12: 1448. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121448

APA StyleDababneh, S., Ardehali, A., Badesha, J., & Laksman, Z. (2025). The Utility of Genome-Wide Association Studies in Inherited Arrhythmias and Cardiomyopathies. Genes, 16(12), 1448. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121448