Genetic Testing in Periodontitis: A Narrative Review on Current Applications, Limitations, and Future Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Genetic Architecture of Periodontitis

3.1. Inflammatory Cytokine Genes in Periodontitis

3.2. GWAS-Identified Susceptibility Loci for Periodontitis

3.3. Polygenic Risk Scores in Periodontitis

4. Host Susceptibility to Periodontal Disease: Emerging Molecular and Genetic Indicators

5. The Role of the Oral Microbiome in Periodontal Disease

6. Genetic Polymorphism in Gingivitis

7. Genetic Polymorphisms in Periodontitis and Gingivitis

8. Genetic Polymorphisms Related to Periodontitis Associated with Systemic Diseases

9. Genetic Polymorphisms Across Ethnic Groups

10. Point-of-Care for Detecting Oral Dysbiosis

Current Point-of-Care Technologies for Dysbiosis Detection

11. Point-of-Care and Genetic Testing for Early Detection of Gingivitis and Periodontitis

11.1. Barriers to Clinical Adoption of Genetic Tests

11.2. Ancestry Bias, Equity, and Ongoing Efforts to Diversify Genomic Datasets

12. Future Perspectives

12.1. Evolution Towards Precision Periodontics

12.2. Polygenic Risk Scores

12.3. Targeting Rare and Early-Onset Forms

12.4. Integration with Advanced Diagnostics

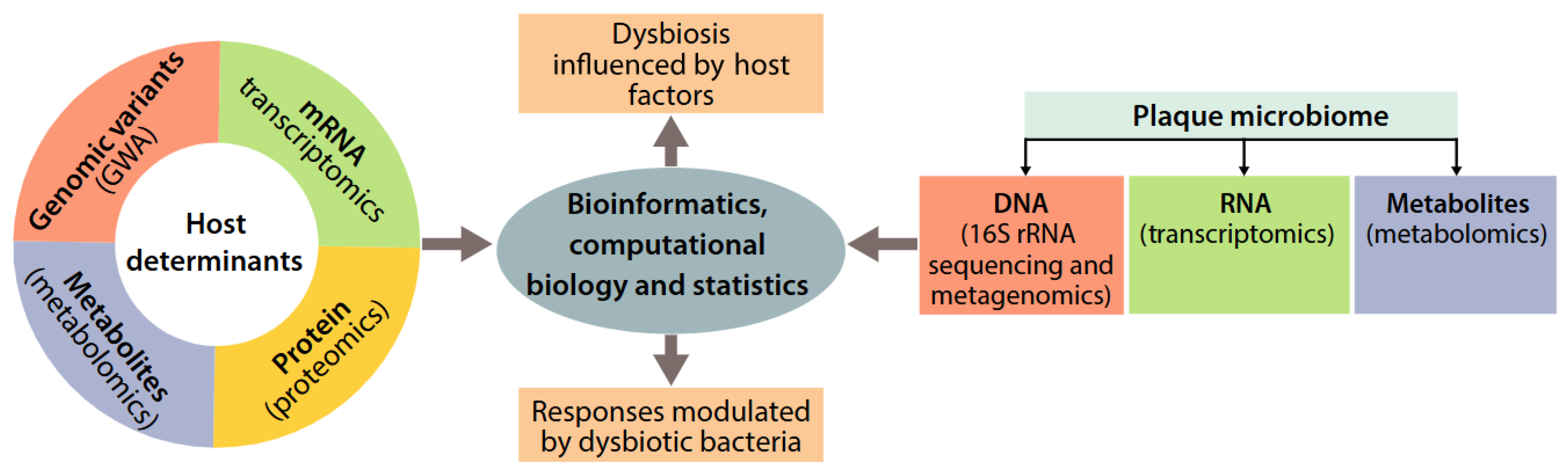

12.5. Genetics, Oral Microbiome, and Protein Biomarkers in Multi-Omic Risk Models

12.6. Current Limitations

13. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Dietrich, N.T.; Feres, M.; Fine, D.H.; Flemmig, T.F.; Garcia, R.; Giannobile, W.V.; Graziani, F.; Greenwell, H. Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89 (Suppl. S1), S173–S182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, M.; Polizzi, A.; Santonocito, S.; Romano, A.; Lombardi, T.; Isola, G. Impact of Oral Microbiome in Periodontal Health and Periodontitis: A Critical Review on Prevention and Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carra, M.C.; Rangé, H.; Caligiuri, G.; Bouchard, P. Periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: A critical appraisal. Periodontol. 2000 2023. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, M.; Marco Del Castillo, A.; Jepsen, S.; Gonzalez-Juanatey, J.R.; D’Aiuto, F.; Bouchard, P.; Chapple, I.; Dietrich, T.; Gotsman, I.; Graziani, F.; et al. Periodontitis and cardiovascular diseases: Consensus report. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 268–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.Z.; Yuan, Y.H.; Liu, H.H.; Li, S.S.; Zhang, B.W.; Chen, W.; An, Z.J.; Chen, S.Y.; Wu, Y.Z.; Han, B.; et al. Epidemiologic relationship between periodontitis and type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Chavakis, T. Local and systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory comorbidities. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajishengallis, G. Interconnection of periodontal disease and comorbidities: Evidence, mechanisms, and implications. Periodontol. 2000 2022, 89, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brookes, A.J. The essence of SNPs. Gene 1999, 234, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignal, A.; Milan, D.; SanCristobal, M.; Eggen, A. A review on SNP and other types of molecular markers and their use in animal genetics. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2002, 34, 275–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visscher, P.M.; Wray, N.R.; Zhang, Q.; Sklar, P.; McCarthy, M.I.; Brown, M.A.; Yang, J. 10 Years of GWAS Discovery: Biology, Function, and Translation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 101, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.I.; Abecasis, G.R.; Cardon, L.R.; Goldstein, D.B.; Little, J.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Hirschhorn, J.N. Genome-wide association studies for complex traits: Consensus, uncertainty and challenges. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, A.; Cai, H.; Zhang, R.; Cheng, R.; Hu, T. Association between polymorphisms of anti-inflammatory gene alleles and periodontitis risk in a Chinese Han population. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 6689–6700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zheng, Q.; Xu, M.; Zeng, C.; Deng, X. Association between circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D metabolites and periodontitis: Results from the NHANES 2009-2012 and Mendelian randomization study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2023, 50, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornman, K.S.; Crane, A.; Wang, H.Y.; di Giovine, F.S.; Newman, M.G.; Pirk, F.W.; Wilson, T.G., Jr.; Higginbottom, F.L.; Duff, G.W. The interleukin-1 genotype as a severity factor in adult periodontal disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1997, 24, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, X.; Sun, W. Association Between Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (G-308A) Polymorphism and Chronic Periodontitis, Aggressive Periodontitis, and Peri-implantitis: A Meta-analysis. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2021, 21, 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Liu, C.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, N.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L. Association of TNF-α-308G/A, -238G/A, -863C/A, -1031T/C, -857C/T polymorphisms with periodontitis susceptibility: Evidence from a meta-analysis of 52 studies. Medicine 2020, 99, e21851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.M.; Chen, Y.J.; Wu, L.; Cui, L.J.; Hu, D.W.; Zeng, X.T. Tumor necrosis factor-α G-308A (rs1800629) polymorphism and aggressive periodontitis susceptibility: A meta-analysis of 16 case-control studies. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, D.L.; Zhou, J.P.; Jiang, X.J.; Jin, Y.L.; Chang, W.W. Association between TNF-α G-308A (rs1800629) polymorphism and susceptibility to chronic periodontitis and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. J. Periodontal. Res. 2021, 56, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, X.; Sun, W. TNF-α polymorphisms might influence predisposition to periodontitis: A meta-analysis. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 143, 104113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Han, Y.; Mao, M.; Tan, Y.Q.; Leng, W.D.; Zeng, X.T. Interleukin-1β rs1143634 polymorphism and aggressive periodontitis susceptibility: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 2308–2316. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, H.; Roochi, M.M.; Sadeghi, M.; Garajei, A.; Heidar, H.; Meybodi, A.A.; Dallband, M.; Mostafavi, S.; Mostafavi, M.; Salehi, M.; et al. Association between Interleukin-1 Polymorphisms and Susceptibility to Dental Peri-Implant Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemmell, E.; Carter, C.L.; Seymour, G.J. Chemokines in human periodontal disease tissues. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2001, 125, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landuzzi, L.; Ruzzi, F.; Pellegrini, E.; Lollini, P.L.; Scotlandi, K.; Manara, M.C. IL-1 Family Members in Bone Sarcomas. Cells 2024, 13, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Lin, W.; Kluzek, M.; Miotla-Zarebska, J.; Batchelor, V.; Gardiner, M.; Chan, C.; Culmer, P.; Chanalaris, A.; Goldberg, R.; et al. Liposomic lubricants suppress acute inflammatory gene regulation in the joint in vivo. Acta Biomater. 2025, 198, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, S.; Köstel Bal, S.; Egner, W.; Lango Allen, H.; Raza, S.I.; Ma, C.A.; Gürel, M.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, G.; Sabroe, R.A.; et al. Loss of the interleukin-6 receptor causes immunodeficiency, atopy, and abnormal inflammatory responses. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 1986–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamata, H.; Honda, S.; Maeda, S.; Chang, L.; Hirata, H.; Karin, M. Reactive oxygen species promote TNFalpha-induced death and sustained JNK activation by inhibiting MAP kinase phosphatases. Cell 2005, 120, 649–661. [Google Scholar]

- Ip, W.K.E.; Hoshi, N.; Shouval, D.S.; Snapper, S.; Medzhitov, R. Anti-inflammatory effect of IL-10 mediated by metabolic reprogramming of macrophages. Science 2017, 356, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, A.; Shen, F.; Hanel, W.; Mossman, K.; Tocker, J.; Swart, D.; Gaffen, S.L. Distinct functional motifs within the IL-17 receptor regulate signal transduction and target gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 7506–7511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggiolini, M.; Walz, A.; Kunkel, S.L. Neutrophil-activating peptide-1/interleukin 8, a novel cytokine that activates neutrophils. J. Clin. Investig. 1989, 84, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayanagi, H.; Kim, S.; Matsuo, K.; Suzuki, H.; Suzuki, T.; Sato, K.; Yokochi, T.; Oda, H.; Nakamura, K.; Ida, N.; et al. RANKL maintains bone homeostasis through c-Fos-dependent induction of interferon-beta. Nature 2002, 416, 744–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuda, H.; Shima, N.; Nakagawa, N.; Mochizuki, S.I.; Yano, K.; Fujise, N.; Sato, Y.; Goto, M.; Yamaguchi, K.; Kuriyama, M.; et al. Identity of osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor (OCIF) and osteoprotegerin (OPG): A mechanism by which OPG/OCIF inhibits osteoclastogenesis in vitro. Endocrinology 1998, 139, 1329–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Xing, M.; Sun, R.; Li, M.; Qian, W.; Fan, M. Identification of potential immune-related genes and infiltrations in temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. Ann. Med. Surg. 2024, 86, 7135–7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehrmann, C.; Dörfer, C.E.; Fawzy El-Sayed, K.M. Toll-like Receptor Expression Profile of Human Stem/Progenitor Cells Form the Apical Papilla. J. Endod. 2020, 46, 1623–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, A.S.; Richter, G.M.; Groessner-Schreiber, B.; Noack, B.; Nothnagel, M.; El Mokhtari, N.-E.; Loos, B.G.; Jepsen, S.; Schreiber, S. Identification of a shared genetic susceptibility locus for coronary heart disease and periodontitis. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganz, T. Defensins: Antimicrobial peptides of innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003, 3, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munz, M.; Willenborg, C.; Richter, G.M.; Jockel-Schneider, Y.; Graetz, C.; Staufenbiel, I.; Wellmann, J.; Berger, K.; Krone, B.; Hoffmann, P.A. A genome-wide association study identifies nucleotide variants at SIGLEC5 and DEFA1A3 as risk loci for periodontitis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 2577–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A.S.; Richter, G.M.; Nothnagel, M.; Manke, T.; Dommisch, H.; Jacobs, G.; Arlt, A.; Rosenstiel, P.; Noack, B.; Groessner-Schreiber, B.A. A genome-wide association study identifies GLT6D1 as a susceptibility locus for periodontitis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dommisch, H.; Hoedke, D.; Lu, E.M.-C.; Schäfer, A.; Richter, G.; Kang, J.; Nibali, L. Genetic Biomarkers for Periodontal Diseases: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2025, 52 (Suppl. S29), 182–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, N.J.; Valenzuela, C.Y.; Jara, L. Interleukin-1 gene cluster polymorphisms associated with periodontal disease in type 2 diabetes. J. Periodontol. 2009, 80, 1590–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, L.; Navarra, C.O.; Pirastu, N.; Lenarda, R.D.; Gasparini, P.; Robino, A. A genome-wide association study identifies an association between variants in EFCAB4B gene and periodontal disease in an Italian isolated population. J. Periodontal Res. 2018, 53, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Y.; Solanki, M.; Zhang, C.; Sasaki, T.; Smith, C.E.; Hu, J.C.; Simmer, J.P. Localizations of Laminin Chains Suggest Their Multifaceted Functions in Mouse Tooth Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Iles, M.M.; Bishop, D.T.; Larvin, H.; Bunce, D.; Wu, B.; Luo, H.; Nibali, L.; Pavitt, S.; Wu, J. Genetic risk factors for periodontitis: A genome-wide association study using UK Biobank data. Clin. Oral Investig. 2025, 29, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, J.R.; Polk, D.E.; Wang, X.; Feingold, E.; Weeks, D.E.; Lee, M.K.; Cuenco, K.T.; Weyant, R.J.; Crout, R.J.; McNeil, D.W. Genome-wide association study of periodontal health measured by probing depth in adults ages 18–49 years. G3 2014, 4, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, G.; Wang, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Liang, X.; Wang, X.; Jiang, J.; Lang, J.; Li, L. Long noncoding RNA HAS2-AS1 mediates hypoxia-induced invasiveness of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Mol. Carcinog. 2017, 56, 2210–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khera, A.V.; Chaffin, M.; Aragam, K.G.; Haas, M.E.; Roselli, C.; Choi, S.H.; Natarajan, P.; Lander, E.S.; Lubitz, S.A.; Ellinor, P.T. Genome-wide polygenic scores for common diseases identify individuals with risk equivalent to monogenic mutations. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1219–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, M.; Takanashi, K.; Matsukubo, T.; Yajima, Y.; Okuda, K.; Sato, T.; Ishihara, K. Transmission of periodontopathic bacteria from natural teeth to implants. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2012, 14, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loe, H.; Theilade, E.; Jensen, S.B. Experimental Gingivitis in Man. J. Periodontol. 1965, 36, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theilade, E.; Wright, W.H.; Jensen, S.B.; Löe, H. Experimental gingivitis in man. II. A longitudinal clinical and bacteriological investigation. J. Periodontal Res. 1966, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Periodontology. Parameter on plaque-induced gingivitis. J. Periodontol. 2000, 71 (Suppl. S5), S851–S852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, S.; Mealey, B.L.; Mariotti, A.; Chapple, I.L.C. Dental plaque-induced gingival conditions. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45 (Suppl. S20), S17–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmstrup, P.; Plemons, J.; Meyle, J. Non-plaque-induced gingival diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45 (Suppl. S20), S28–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, F.S.; Martelli, M.; Rosati, C.; Fanti, E. Vitamin D: Relevance in dental practice. Clin. Cases Miner Bone Metab 2014, 11, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikle, D.D. Vitamin D metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical applications. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhonkar, A.; Gupta, A.; Arya, V. Comparison of Vitamin D Level of Children with Severe Early Childhood Caries and Children with No Caries. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2018, 11, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; He, L.; Xu, J.; Song, W.; Feng, X.; Zhao, Y.; Meng, H. Well-maintained patients with a history of periodontitis still harbor a more disbiotic microbiome than health. J. Periodontol. 2020, 91, 1584–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.L.; Li, H.; Zhang, P.P.; Wang, S.M. Association between vitamin D receptor polymorphisms and periodontitis: A meta-analysis. J. Periodontol. 2012, 83, 1095–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.C.F.; Lima, D.C.; Reis, C.L.B.; Reis, A.L.M.; Rigo, D., Jr.; Segato, R.A.B.; Storrer, C.L.M.; Küchler, E.C.; de Oliveira, D.S.B. Vitamin D receptor FokI and BglI genetic polymorphisms, dental caries, and gingivitis. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2020, 30, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izakovicova Holla, L.; Borilova Linhartova, P.; Kastovsky, J.; Bartosova, M.; Musilova, K.; Kukla, L.; Kukletova, M. Vitamin D Receptor TaqI Gene Polymorphism and Dental Caries in Czech Children. Caries Res. 2017, 51, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartosova, M.; Borilova Linhartova, P.; Musilova, K.; Broukal, Z.; Kukletova, M.; Kukla, L.; Izakovicova Holla, L. Association of the CD14 -260C/T polymorphism with plaque-induced gingivitis depends on the presence of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 32, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dashash, M.; Drucker, D.B.; Hutchinson, I.V.; Bazrafshani, M.R.; Blinkhorn, A.S. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene polymorphism and gingivitis in children. Oral Dis. 2007, 13, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trombelli, L.; Tatakis, D.N.; Scapoli, C.; Bottega, S.; Orlandini, E.; Tosi, M. Modulation of clinical expression of plaque-induced gingivitis. II. Identification of “high-responder” and “low-responder” subjects. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2004, 31, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kinane, D.F.; Stathopoulou, P.G.; Papapanou, P.N. Periodontal diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, S. Vitamin-D receptor (VDR) gene polymorphisms (Taq-I & Apa-I) in Syrian healthy population. Meta Gene 2014, 2, 646–650. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hujoel, P.P. Vitamin D and dental caries in controlled clinical trials: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raftery, T.; Martineau, A.R.; Greiller, C.L.; Ghosh, S.; McNamara, D.; Bennett, K.; Meddings, J.; O’Sullivan, M. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on intestinal permeability, cathelicidin and disease markers in Crohn’s disease: Results from a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2015, 3, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deane, S.; Schroth, R.J.; Sharma, A.; Rodd, C. Combined deficiencies of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and anemia in preschool children with severe early childhood caries: A case-control study. Paediatr. Child Health 2018, 23, e40–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénard, M.; Baudry, J.; Méjean, C.; Lairon, D.; Giudici, K.V.; Etilé, F.; Reach, G.; Hercberg, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Péneau, S. Association between time perspective and organic food consumption in a large sample of adults. Nutr. J. 2018, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.J.; Lee, H.S.; Ju, H.J.; Na, J.Y.; Oh, H.W. A cross-sectional study on the association between vitamin D levels and caries in the permanent dentition of Korean children. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Liu, F.; Pan, Y.; Jin, X.; Wang, H.; Cao, J. BsmI, TaqI, ApaI, and FokI polymorphisms in the vitamin D receptor gene and periodontitis: A meta-analysis of 15 studies including 1338 cases and 1302 controls. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011, 38, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zong, X.; Pan, Y. Associations between vitamin D receptor genetic variants and periodontitis: A meta-analysis. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2019, 77, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlet, G.P.; Trombone, A.P.; Menezes, R.; Letra, A.; Repeke, C.E.; Vieira, A.E.; Martins, W., Jr.; Neves, L.T.; Campanelli, A.P.; Santos, C.F.; et al. The use of chronic gingivitis as reference status increases the power and odds of periodontitis genetic studies: A proposal based in the exposure concept and clearer resistance and susceptibility phenotypes definition. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 39, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Ruiz, J.S.; Ramírez-De Los Santos, S.; Alonso-Sánchez, C.C.; Martínez-Esquivias, F.; Martínez-Pérez, L.A.; Padilla-González, A.C.; Rivera-Santana, G.A.; Guerrero-Velázquez, C.; López-Pulido, E.I.; Guzmán-Flores, J.M. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha polymorphism -308 G/a and its protein in subjects with gingivitis. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2021, 79, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Gupta, N.; Jha, T.; Manzoor, T.B.E. Association of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) gene polymorphisms with periodontitis: A systematic review. GMS Hyg. Infect. Control 2024, 19, Doc53. [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk, A.; Ada, A.O. The roles of ANRIL polymorphisms in periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 1121–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izakovicova, P.; Fassmann, A.; Dusek, L.; Izakovicova Holla, L. Glutathione S-transferase M1, T1, and P1 polymorphisms and periodontitis in a Caucasian population: A case-control study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, N. Commentary: How small is small? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 38, 274–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wojczynski, M.K.; Tiwari, H.K. Definition of phenotype. Adv. Genet. 2008, 60, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Edwards, B.J.; Haynes, C.; Levenstien, M.A.; Finch, S.J.; Gordon, D. Power and sample size calculations in the presence of phenotype errors for case/control genetic association studies. BMC Genet. 2005, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zondervan, K.T.; Cardon, L.R. Designing candidate gene and genome-wide case-control association studies. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 2492–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buyske, S.; Yang, G.; Matise, T.C.; Gordon, D. When a case is not a case: Effects of phenotype misclassification on power and sample size requirements for the transmission disequilibrium test with affected child trios. Hum. Hered. 2009, 67, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelou, E.; Fellay, J.; Colombo, S.; Martinez-Picado, J.; Obel, N.; Goldstein, D.B.; Telenti, A.; Ioannidis, J.P. Impact of phenotype definition on genome-wide association signals: Empirical evaluation in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 173, 1336–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, A.S.; Jepsen, S.; Loos, B.G. Periodontal genetics: A decade of genetic association studies mandates better study designs. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011, 38, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, P.R.; Hansell, A.L.; Fortier, I.; Manolio, T.A.; Khoury, M.J.; Little, J.; Elliott, P. Size matters: Just how big is BIG?: Quantifying realistic sample size requirements for human genome epidemiology. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 38, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, S.R.; de Arruda, J.A.A.; Schneider, A.H.; Bemquerer, L.M.; de Souza, R.M.S.; Barbim, P.; de Mattos-Pereira, G.H.; Calderaro, D.C.; Machado, C.C.; Alves, S.F. Neutrophil extracellular traps in rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis: Contribution of PADI4 gene polymorphisms. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2024, 51, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, X.; Xiao, L.; Xie, C.; Xuan, D.; Luo, G. Gene polymorphisms and periodontitis. Periodontol. 2000 2011, 56, 102–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, P.M.; Zygogianni, P.; Griffiths, G.S.; Tomaz, M.; Parkar, M.; D’Aiuto, F.; Tonetti, M. Functional gene polymorphisms in aggressive and chronic periodontitis. J. Dent. Res. 2005, 84, 1149–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eto, M.; Watanabe, K.; Ishii, K. A racial difference in apolipoprotein E allele frequencies between the Japanese and Caucasian populations. Clin. Genet. 1986, 30, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzeldemir, E.; Gunhan, M.; Ozcelik, O.; Tastan, H. Interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene polymorphisms in Turkish patients with localized aggressive periodontitis. J. Oral Sci. 2008, 50, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ren, X.Y.; Xu, L.; Meng, H.X. Interleukin-1 family polymorphisms in aggressive periodontitis patients and their relatives. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2008, 40, 28–33. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Holla, L.I.; Fassmann, A.; Stejskalová, A.; Znojil, V.; Vanĕk, J.; Vacha, J. Analysis of the interleukin-6 gene promoter polymorphisms in Czech patients with chronic periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 2004, 75, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, R.; Liu, G.; Yang, C.; Huang, C.; Wu, C.; Christiani, D.C. The G to C polymorphism at −174 of the interleukin-6 gene is rare in a Southern Chinese population. Pharmacogenetics 2001, 11, 699–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.M.; Yan, Y.X.; Xie, C.J.; Fan, W.H.; Xuan, D.Y.; Wang, C.X.; Chen, L.; Sun, S.Y.; Xie, B.Y.; Zhang, J.C. Association among interleukin-6 gene polymorphism, diabetes and periodontitis in a Chinese population. Oral Dis. 2009, 15, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baier, R.J.; Loggins, J.; Yanamandra, K. IL-10, IL-6 and CD14 polymorphisms and sepsis outcome in ventilated very low birth weight infants. BMC Med. 2006, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, T.; Ota, N.; Yoshida, H.; Watanabe, S.; Suzuki, T.; Emi, M. Allelic variants in the interleukin-6 gene and essential hypertension in Japanese women. Genes Immun. 1999, 1, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamid, Y.H.; Rose, C.S.; Urhammer, S.A.; Glümer, C.; Nolsøe, R.; Kristiansen, O.P.; Mandrup-Poulsen, T.; Borch-Johnsen, K.; Jorgensen, T.; Hansen, T. Variations of the interleukin-6 promoter are associated with features of the metabolic syndrome in Caucasian Danes. Diabetologia 2005, 48, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, S.L.; Ahn-Luong, L.; Garnero, P.; Humphries, S.E.; Greenspan, S.L. Two promoter polymorphisms regulating interleukin-6 gene expression are associated with circulating levels of C-reactive protein and markers of bone resorption in postmenopausal women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, J.C.; Schneider, J.A.; Tanguay, D.A.; Choi, J.; Acharya, T.; Stanley, S.E.; Jiang, R.; Messer, C.J.; Chew, A.; Han, J.H. Haplotype variation and linkage disequilibrium in 313 human genes. Science 2001, 293, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Nayak, P.A.; Rana, S. Point of Care- A Novel Approach to Periodontal Diagnosis-A Review. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, Ze01–Ze06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paqué, P.N.; Herz, C.; Jenzer, J.S.; Wiedemeier, D.B.; Attin, T.; Bostanci, N.; Belibasakis, G.N.; Bao, K.; Körner, P.; Fritz, T. Microbial Analysis of Saliva to Identify Oral Diseases Using a Point-of-Care Compatible qPCR Assay. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolińska, E.; Wiśniewski, P.; Pietruska, M. Periodontal Molecular Diagnostics: State of Knowledge and Future Prospects for Clinical Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.; Tay, J.R.H.; Balan, P.; Ong, M.M.A.; Bostanci, N.; Belibasakis, G.N.; Seneviratne, C.J. Metagenomic sequencing provides new insights into the subgingival bacteriome and aetiopathology of periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 2021, 56, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopealaakso, T.K.; Thomas, J.T.; Pätilä, T.; Penttala, M.; Sakellari, D.; Grigoriadis, A.; Gupta, S.; Sorsa, T.; Räisänen, I.T. Periodontitis, Metabolic Syndrome and Diabetes: Identifying Patients at Risk for Three Common Diseases Using the aMMP-8 Rapid Test at the Dentist’s Office. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aji, N.R.A.S.; Räisänen, I.T.; Rathnayake, N.; Lundy, F.T.; Mc Crudden, M.T.C.; Goyal, L.; Sorsa, T.; Gupta, S. aMMP-8 POCT vs. Other Potential Biomarkers in Chair-Side Diagnostics and Treatment Monitoring of Severe Periodontitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallio, E.; Puolakkainen, T.; Tervahartiala, T.; Snäll, J.; Marttila, E.; Sorsa, T.; Uittamo, J. Applicability of an active matrix metalloproteinase-8 point-of-care test in an oral and maxillofacial surgery clinic: A pilot study. Odontology 2024, 112, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aji, N.R.A.S.; Sahni, V.; Penttala, M.T.; Sakellari, D.; Grigoriadis, A.; Pätilä, T.; Pärnänen, P.; Neefs, D.; Pfützner, A.; Gupta, S. Oral Medicine and Oral Clinical Chemistry Game Changers for Future Plaque Control and Maintenance: PerioSafe® aMMP-8 POCT, Lumoral® 2× PDT-and Lingora® Fermented Lingonberry Oral Rinse-Treatments. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buduneli, N.; Bıyıkoğlu, B.; Kinane, D.F. Utility of gingival crevicular fluid components for periodontal diagnosis. Periodontol. 2000 2024, 95, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähteenmäki, H.; Umeizudike, K.A.; Heikkinen, A.M.; Räisänen, I.T.; Rathnayake, N.; Johannsen, G.; Tervahartiala, T.; Nwhator, S.O.; Sorsa, T. aMMP-8 Point-of-Care/Chairside Oral Fluid Technology as a Rapid, Non-Invasive Tool for Periodontitis and Peri-Implantitis Screening in a Medical Care Setting. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, K.; Pelekos, G.; Jin, L.; Tonetti, M.S. Diagnostic accuracy of a point-of-care aMMP-8 test in the discrimination of periodontal health and disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2021, 48, 1051–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorsa, T.; Sahni, V.; Buduneli, N.; Gupta, S.; Räisänen, I.T.; Golub, L.M.; Lee, H.M.; Pätilä, T.; Bostanci, N.; Meurman, J. Active matrix metalloproteinase-8 (aMMP-8) point-of-care test (POCT) in the COVID-19 pandemic. Expert Rev. Proteomics 2021, 18, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caton, J.G.; Armitage, G.; Berglundh, T.; Chapple, I.L.C.; Jepsen, S.; Kornman, K.S.; Mealey, B.L.; Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Tonetti, M.S. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions—Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45 (Suppl. S20), S1–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räisän Räisänen, I.T.; Sorsa, T.; Tervahartiala, T.; Raivisto, T.; Heikkinen, A.M. Low association between bleeding on probing propensity and the salivary aMMP-8 levels in adolescents with gingivitis and stage I periodontitis. J. Periodontal. Res. 2021, 56, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabors, T.W.; McGlennen, R.C.; Thompson, D. Salivary testing for periodontal disease diagnosis and treatment. Dent. Today 2010, 29, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eguchi, T.; Koshy, G.; Umeda, M.; Iwanami, T.; Suga, J.; Nomura, Y.; Kawanami, M.; Ishikawa, I. Microbial changes in patients with acute periodontal abscess after treatment detected by PadoTest. Oral Dis. 2008, 14, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moya-Villaescusa, M.J.; Sánchez-Pérez, A.; Mehdi Al-Lal, N.; Jornet-García, A.; Montoya-Carralero, J.M. Validation of a Novel Diagnostic Test for Assessing the Risk of Peri-Implantitis through the Identification of the Microorganisms Present: A Pilot Clinical Study of Periopoc. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, D.; Johannsen, B.; Specht, M.; Lüddecke, J.; Rombach, M.; Hin, S.; Paust, N.; von Stetten, F.; Zengerle, R.; Herz, C. OralDisk: A Chair-Side Compatible Molecular Platform Using Whole Saliva for Monitoring Oral Health at the Dental Practice. Biosensors 2021, 11, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Z.; Yu, Y.; Cheng, P.; Zhao, L.; Petrovic, B.; Li, A.; Xu, F.; Li, Y.; You, M. Recent advances of oral fluids-based point-of-care testing platforms for oral disease diagnosis. Transl. Dent. Res. 2025, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nibali, L.; Divaris, K.; Lu, E.M. The promise and challenges of genomics-informed periodontal disease diagnoses. Periodontol. 2000 2024, 95, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.M.; Vassos, E. Polygenic risk scores: From research tools to clinical instruments. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slunecka, J.L.; van der Zee, M.D.; Beck, J.J.; Johnson, B.N.; Finnicum, C.T.; Pool, R.; Hottenga, J.J.; de Geus, E.J.C.; Ehli, E.A. Implementation and implications for polygenic risk scores in healthcare. Hum. Genom. 2021, 15, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siena, L.M.; Baccolini, V.; Riccio, M.; Rosso, A.; Migliara, G.; Sciurti, A.; Isonne, C.; Iera, J.; Pierri, F.; Marzuillo, C. Weighing the evidence on costs and benefits of polygenic risk-based approaches in clinical practice: A systematic review of economic evaluations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2025, 112, 1735–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitipaldi, H.; Franks, P.W. Ethnic, gender and other sociodemographic biases in genome-wide association studies for the most burdensome non-communicable diseases: 2005-2022. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2023, 32, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, D.; Hui, D.; Hammond, D.A.; Wonkam, A.; Tishkoff, S.A. Importance of Including Non-European Populations in Large Human Genetic Studies to Enhance Precision Medicine. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data. Sci. 2022, 5, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatumo, S.; Chikowore, T.; Choudhury, A.; Ayub, M.; Martin, A.R.; Kuchenbaecker, K. A roadmap to increase diversity in genomic studies. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taliun, D.; Harris, D.N.; Kessler, M.D.; Carlson, J.; Szpiech, Z.A.; Torres, R.; Taliun, S.A.G.; Corvelo, A.; Gogarten, S.M.; Kang, H.M. Sequencing of 53,831 diverse genomes from the NHLBI TOPMed Program. Nature 2021, 590, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bostanci, N.; Belibasakis, G.N. Precision periodontal care: From omics discoveries to chairside diagnostics. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Bartold, P.M.; Ivanovski, S. The emerging role of small extracellular vesicles in saliva and gingival crevicular fluid as diagnostics for periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 2022, 57, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Xiang, R.; Chen, W.; Peng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, W.; Tang, L. CircRNA-mediated heterogeneous ceRNA regulation mechanism in periodontitis and peri-implantitis. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yu, N.; Arce, R.M. Periodontal inflammation: Integrating genes and dysbiosis. Periodontol. 2000 2020, 82, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samodova, D.; Stankevic, E.; Søndergaard, M.S.; Hu, N.; Ahluwalia, T.S.; Witte, D.R.; Belstrøm, D.; Lubberding, A.F.; Jagtap, P.D.; Hansen, T. Salivary proteomics and metaproteomics identifies distinct molecular and taxonomic signatures of type-2 diabetes. Microbiome 2025, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoppers, B.M. Framework for responsible sharing of genomic and health-related data. Hugo J. 2014, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, E.W.; Evans, B.J.; Hazel, J.W.; Rothstein, M.A. The law of genetic privacy: Applications, implications, and limitations. J. Law Biosci. 2019, 6, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Encoded Protein | Functional Role | Periodontitis-Associated Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL1A | Interleukin-1 alpha | Early pro-inflammatory signaling, epithelial alarmin | Promotes neutrophil infiltration, bone resorption [23] |

| IL1B | Interleukin-1 beta | Pro-inflammatory cytokine, fever induction | Drives local inflammation and tissue degradation [24] |

| IL6 | Interleukin-6 | Acute-phase response, B-cell differentiation | Correlates with clinical attachment loss [25] |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha | Master regulator of inflammation, apoptosis inducer | Enhances RANKL expression and osteoclastogenesis [26] |

| IL10 | Interleukin-10 | Anti-inflammatory cytokine | Downregulates IL1 and TNFA, low expression linked to risk [27] |

| IL17A/F | Interleukin-17A/F | Th17 cytokines, neutrophil recruitment | Induce MMPs and RANKL, contribute to chronic inflammation [28] |

| IL8 (CXCL8) | Interleukin-8 | Neutrophil chemoattractant | Elevated in GCF of periodontitis patients [29] |

| RANKL | Receptor activator of NF-κB ligand | Osteoclast differentiation and activation | Increased expression causes alveolar bone loss [30] |

| OPG | Osteoprotegerin | RANKL decoy receptor, inhibits bone resorption | Decreased expression associated with bone destruction [31] |

| MMP1/8/9 | Matrix metalloproteinases | ECM degradation enzymes | Collagen breakdown in periodontal ligament and alveolar bone [32] |

| TLR2/4 | Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 | Innate immunity, bacterial LPS recognition | Polymorphisms affect pathogen response and inflammation [33] |

| Gene | Encoded Protein/Feature | Putative Function | Association Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIGLEC5 | Sialic acid-binding Ig-like lectin 5 | Immune inhibitory receptor on neutrophils | Genome-wide association in AgP and CP [34] |

| DEFA1A3 | α-Defensins 1–3 (HNP1–3) | Antimicrobial peptides in neutrophils | CNV associated with CP risk [36] |

| GLT6D1 | Glycosyltransferase-like domain protein | Potential epithelial/neutrophil glycosylation | GWAS-confirmed in CP and AgP [37] |

| EFCAB4B | EF-hand calcium-binding domain-containing 4B | Calcium signaling regulation in immune/epithelial cells | Novel locus in isolated Italian population [40] |

| LAMA2 | Laminin subunit α2 | ECM structure and epithelial adhesion | GWAS [41] |

| ARHGAP18 | Rho GTPase-activating protein 18 | Cytoskeletal remodeling and epithelial integrity | Candidate locus [43] |

| HAS2/HAS2-AS1 | Hyaluronan synthase 2/Antisense RNA | Hyaluronic acid metabolism and matrix signaling | Functional candidate in epithelial barrier modulation [44] |

| RP11-61G19.1 | Long non-coding RNA locus | Likely regulatory, function unknown | Genome-wide significant locus [42] |

| HIST1H3L | Histone H3-like protein | Chromatin and epigenetic regulation | Novel association in UK Biobank data [42] |

| Gene | Polymorphism | Study Design | Sample Size | Population | Association with Gingivitis | Replication Status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VDR | VDR FokI (rs2228570) | Cross-sectional | 353 | Brazilian children | No association | Not replicated | [57] |

| VDR | VDR BglI (rs739837) | Cross-sectional | 353 | Brazilian children | No association | Not replicated | [57] |

| VDR | VDR TaqI (rs731236) | Cross-sectional with longitudinal follow-up | 51 | Czech children | Associated. Recognized as risk factor for gingivitis. | Single study, replicated findings | [58] |

| CD14 | CD14 −260C/T | Case–control | 590 | Caucasian children with plaque-induced gingivitis | No general association, but CT/TT genotypes more frequent in gingivitis with P. gingivalis. | Single study | [59] |

| IL-1 | IL-1RN VNTR (IL-1Ra) | Case–control | 146 | Caucasian children | Associated. IL-1RN*2 (A2) allele is protective | Single study, replicated elsewhere | [60] |

| IL-10 | IL10 −592C | Case–control | 608 | Brazilian (mixed ancestry, mostly Caucasian) adults affected by chronic gingivitis | Hyporesponsive SNP, prevalent in gingivitis and protective against periodontitis. | Observed in multiple studies | [71] |

| TLR4 | TLR4 −299G | Case–control | 608 | Brazilian (mixed ancestry, mostly Caucasian) adults affected by chronic gingivitis | Hyporesponsive SNP, prevalent in gingivitis and protective against periodontitis. | Observed in multiple studies | [71] |

| TNF-α | TNF-α −308G/A | Case–control | 171 | Adult Mexican Cohort | A/A genotype and allele A are protective, G/A is associated with increased HDL-C | Single study | [72] |

| Kit/Platform | Target/Biomarker | Method | Regulatory Status | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PerioSafe®/ORALyzer® | Active MMP-8 (aMMP-8) | Lateral-flow immunoassay with digital reader | FDA-approved, CE-marked | Single biomarker; methodological variability; further studies needed for integration with other markers |

| iai PadoTest | Periodontal pathogens | qPCR (external laboratory) | CE-marked, not FDA approved | No individual predictive value; supportive test |

| MyPerioPath® | Periodontal pathogens | qPCR (external laboratory) | CLIA-certified, not FDA approved | Limited predictive value; longer turnaround time |

| PerioPOC®/HR5™ | High-risk bacterial panel | Rapid qPCR | CE-marked | Clinical evidence still limited |

| OralDisk | Periodontal and cariogenic bacteria | Microfluidics + real-time PCR | In development, not yet approved | Requires dedicated device; limited to research use |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Modafferi, C.; Grippaudo, C.; Corvaglia, A.; Cristi, V.; Amato, M.; Rigotti, P.; Polizzi, A.; Isola, G. Genetic Testing in Periodontitis: A Narrative Review on Current Applications, Limitations, and Future Perspectives. Genes 2025, 16, 1308. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111308

Modafferi C, Grippaudo C, Corvaglia A, Cristi V, Amato M, Rigotti P, Polizzi A, Isola G. Genetic Testing in Periodontitis: A Narrative Review on Current Applications, Limitations, and Future Perspectives. Genes. 2025; 16(11):1308. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111308

Chicago/Turabian StyleModafferi, Clarissa, Cristina Grippaudo, Andrea Corvaglia, Vittoria Cristi, Mariacristina Amato, Pietro Rigotti, Alessandro Polizzi, and Gaetano Isola. 2025. "Genetic Testing in Periodontitis: A Narrative Review on Current Applications, Limitations, and Future Perspectives" Genes 16, no. 11: 1308. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111308

APA StyleModafferi, C., Grippaudo, C., Corvaglia, A., Cristi, V., Amato, M., Rigotti, P., Polizzi, A., & Isola, G. (2025). Genetic Testing in Periodontitis: A Narrative Review on Current Applications, Limitations, and Future Perspectives. Genes, 16(11), 1308. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111308