Gene Expression Dynamics Underlying Muscle Aging in the Hawk Moth Manduca sexta

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Model Organism

2.2. Enzyme Spectrophotometric Assays

2.3. RNA Extraction

2.4. Illumina Sequencing and Differential Gene Expression Analysis

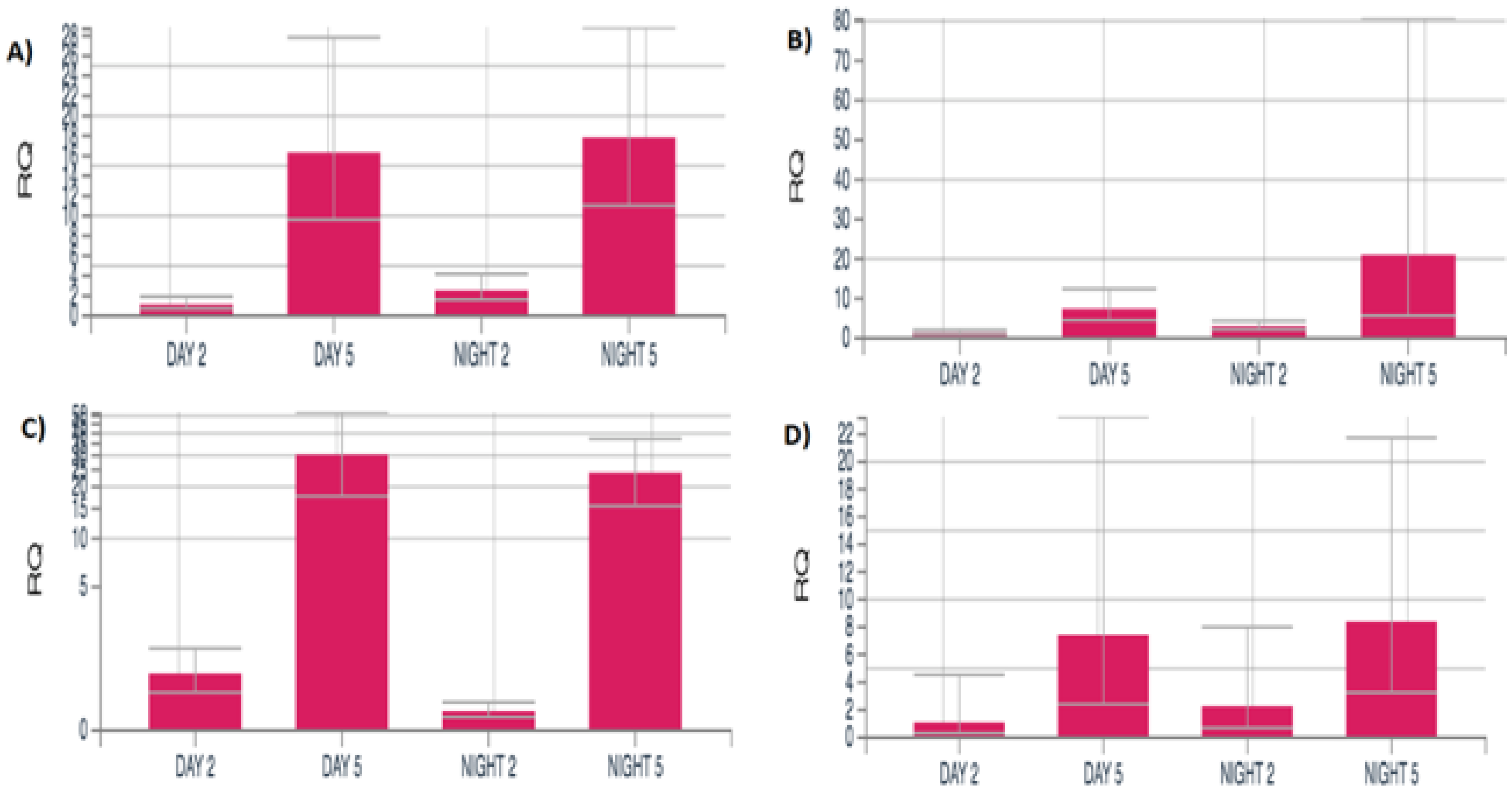

2.5. Orthogonal Confirmation of RNA-Seq Data by qRT-PCR

2.6. Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG Pathway Annotation

3. Results

3.1. RNA-Seq

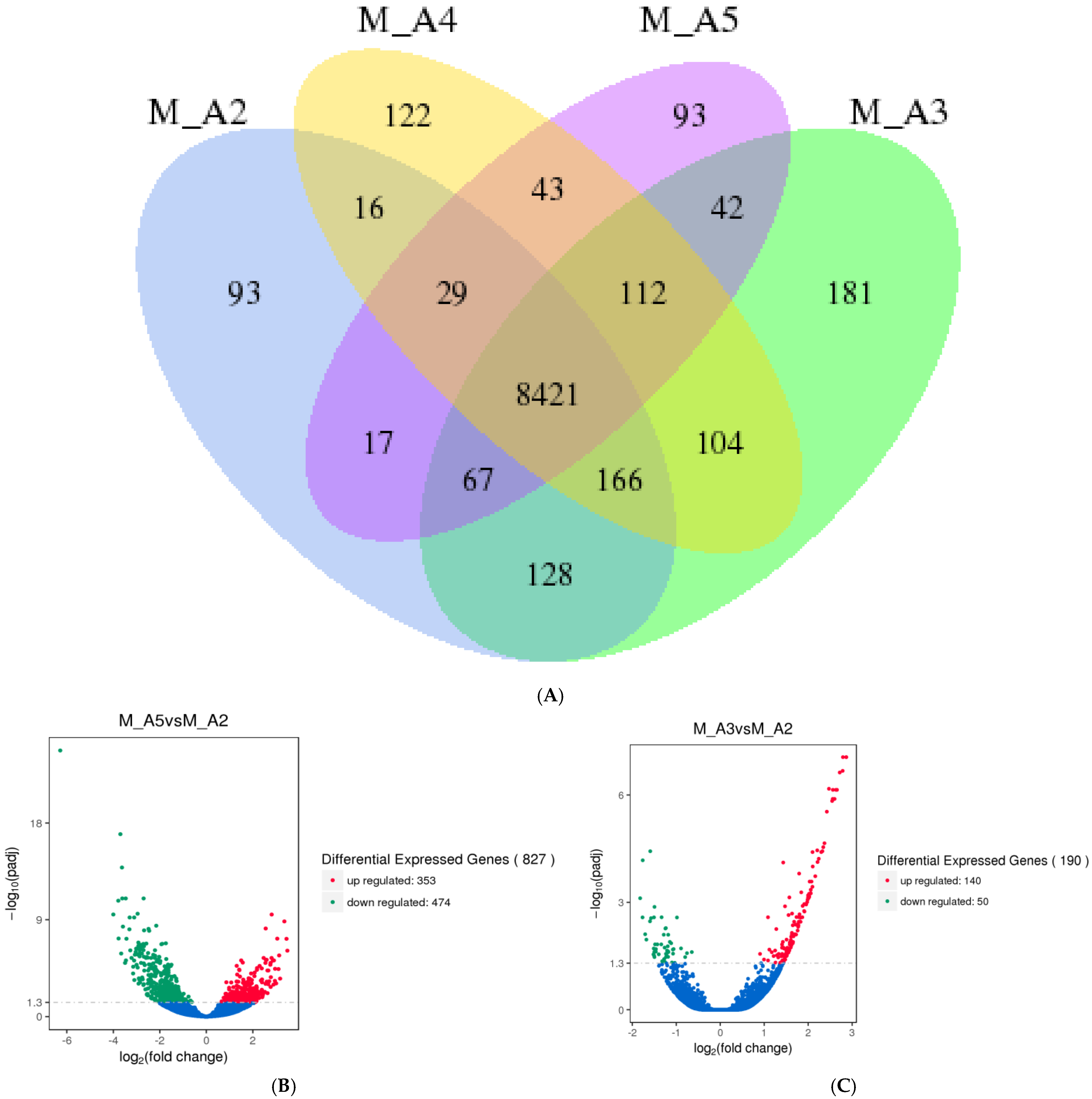

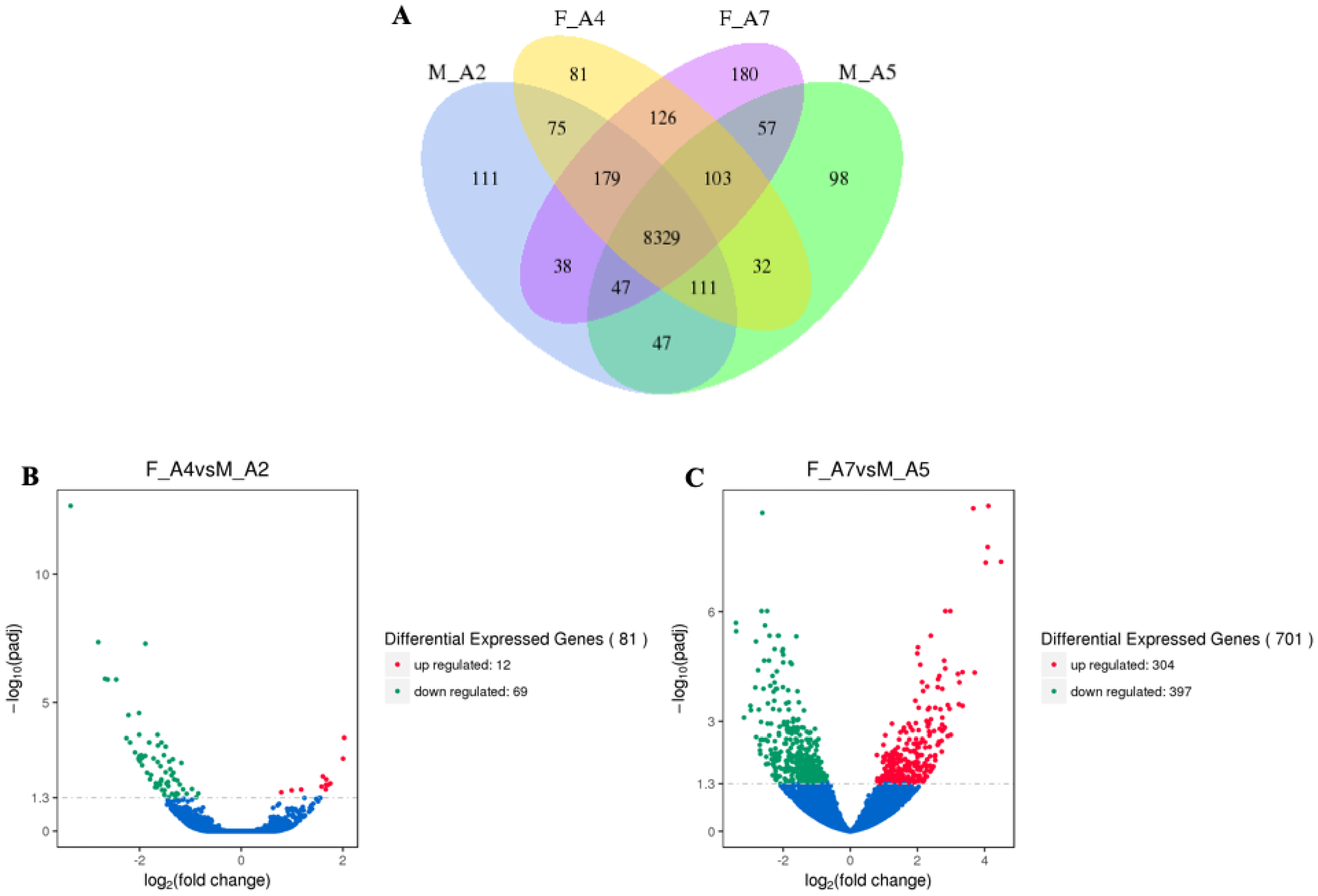

3.1.1. Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) in M. sexta Flight Muscle Across Age Classes

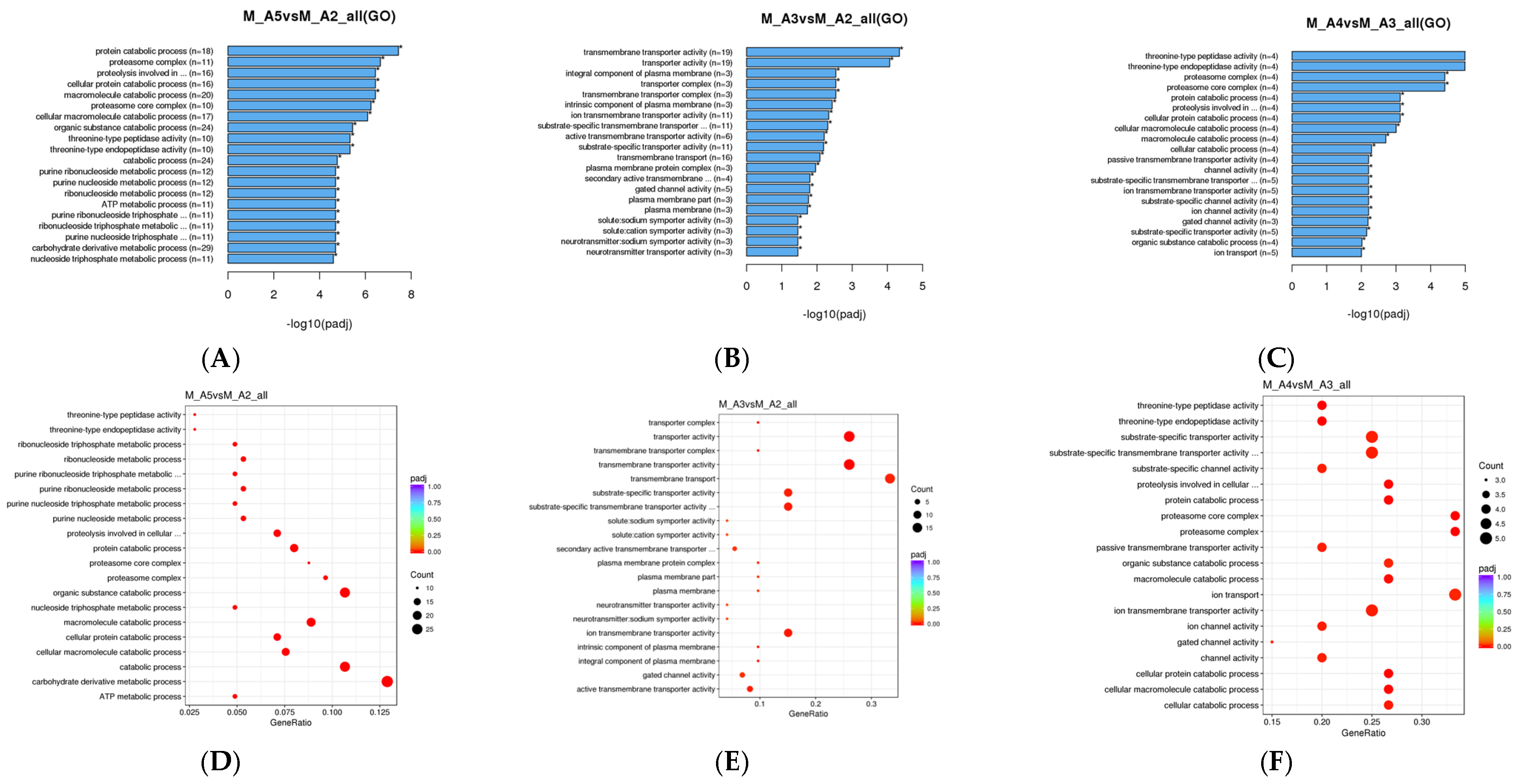

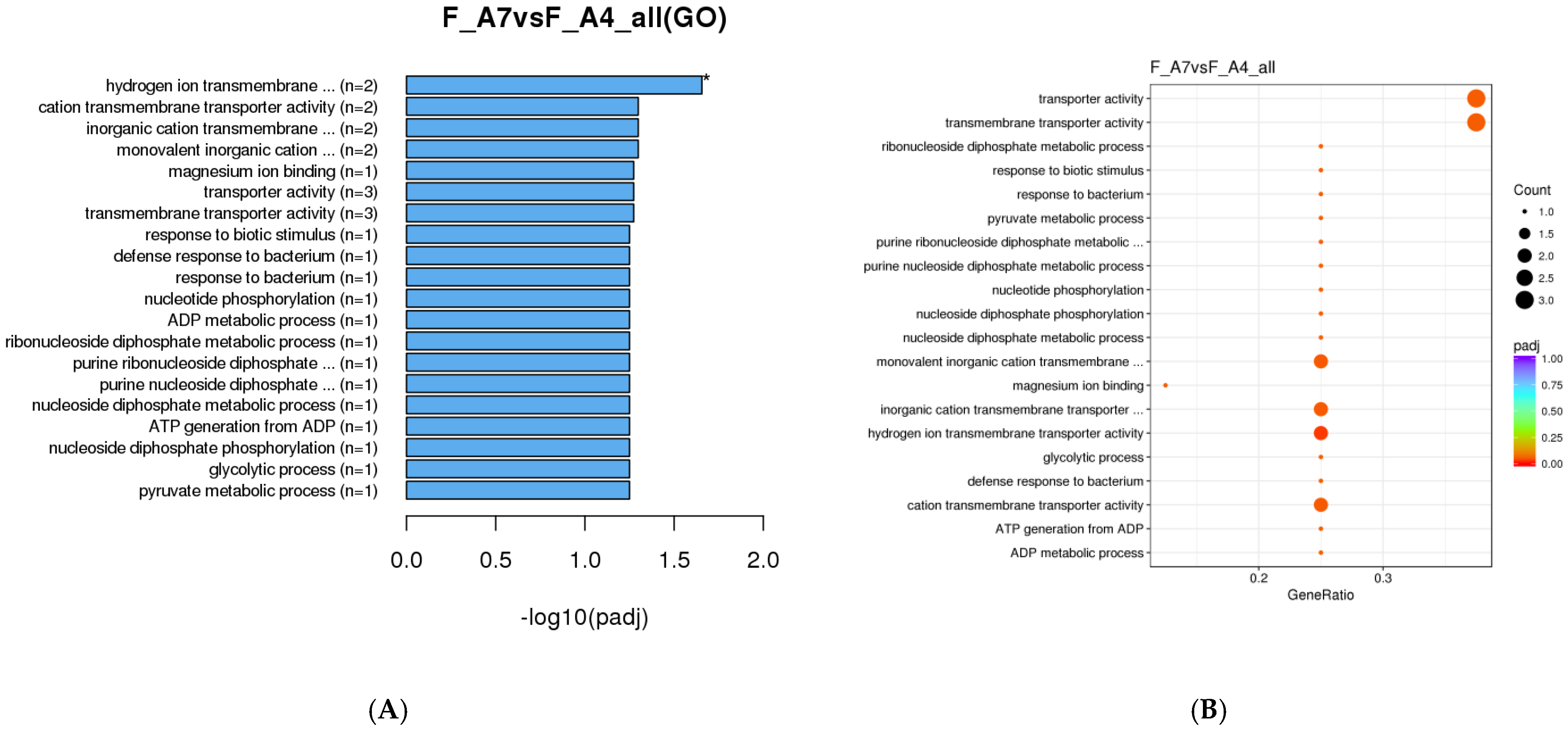

3.1.2. Gene Ontology (GO) Enrichment Analysis

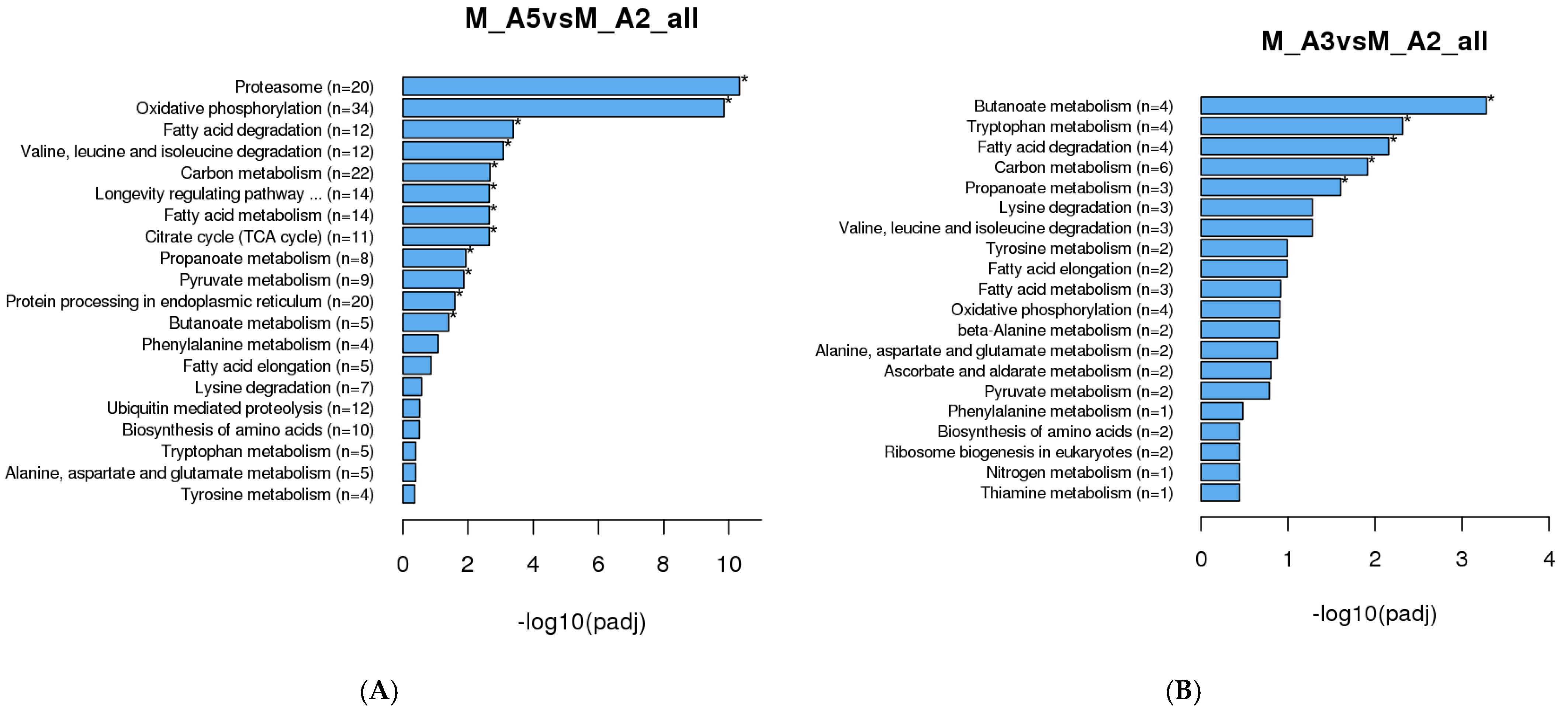

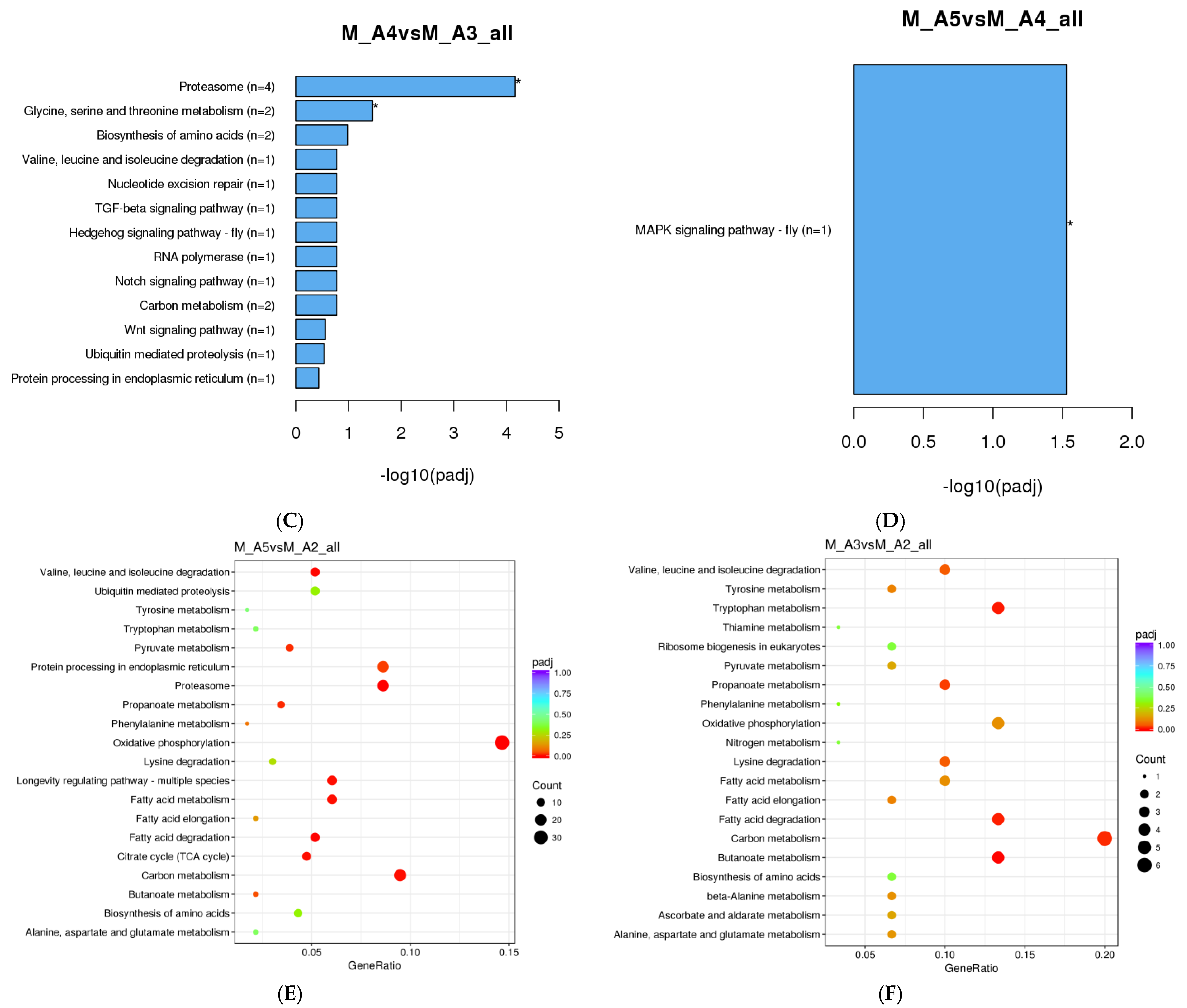

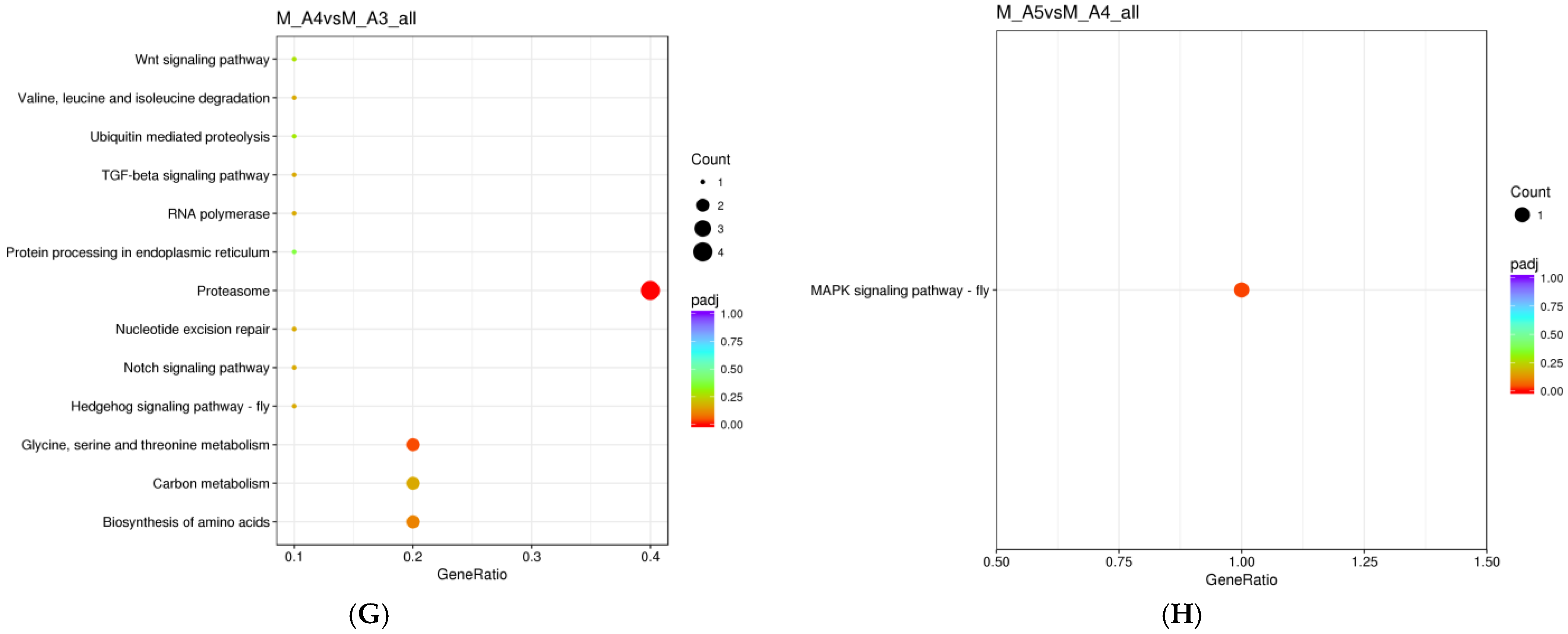

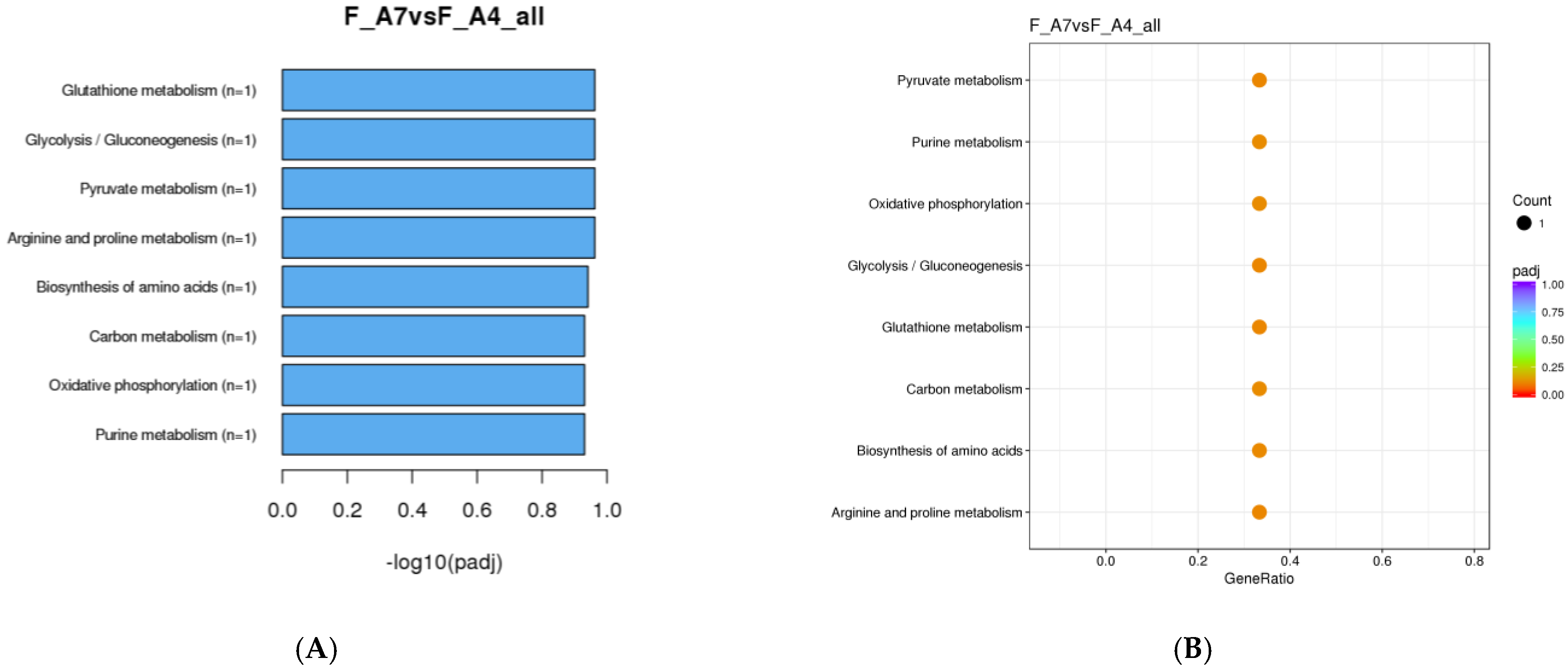

3.1.3. KEGG Enrichment Analysis

3.1.4. Inventory of DEGs in Middle-Aged to Advanced-Aged Male M. sexta Flight Muscle

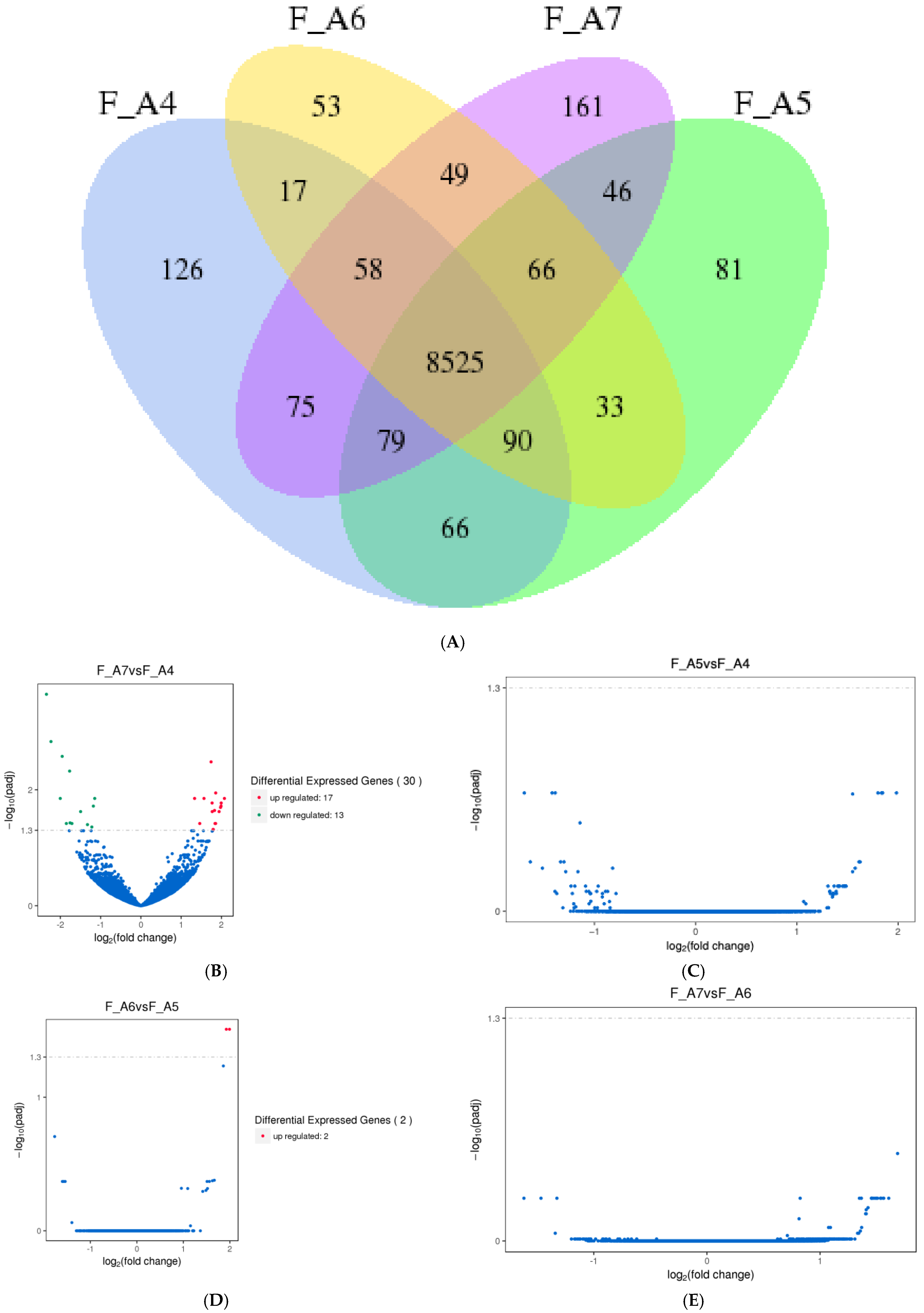

3.1.5. Progressive DEG Changes in Female Moths from Middle to Advanced Age

3.2. Metabolic Enzyme Activity

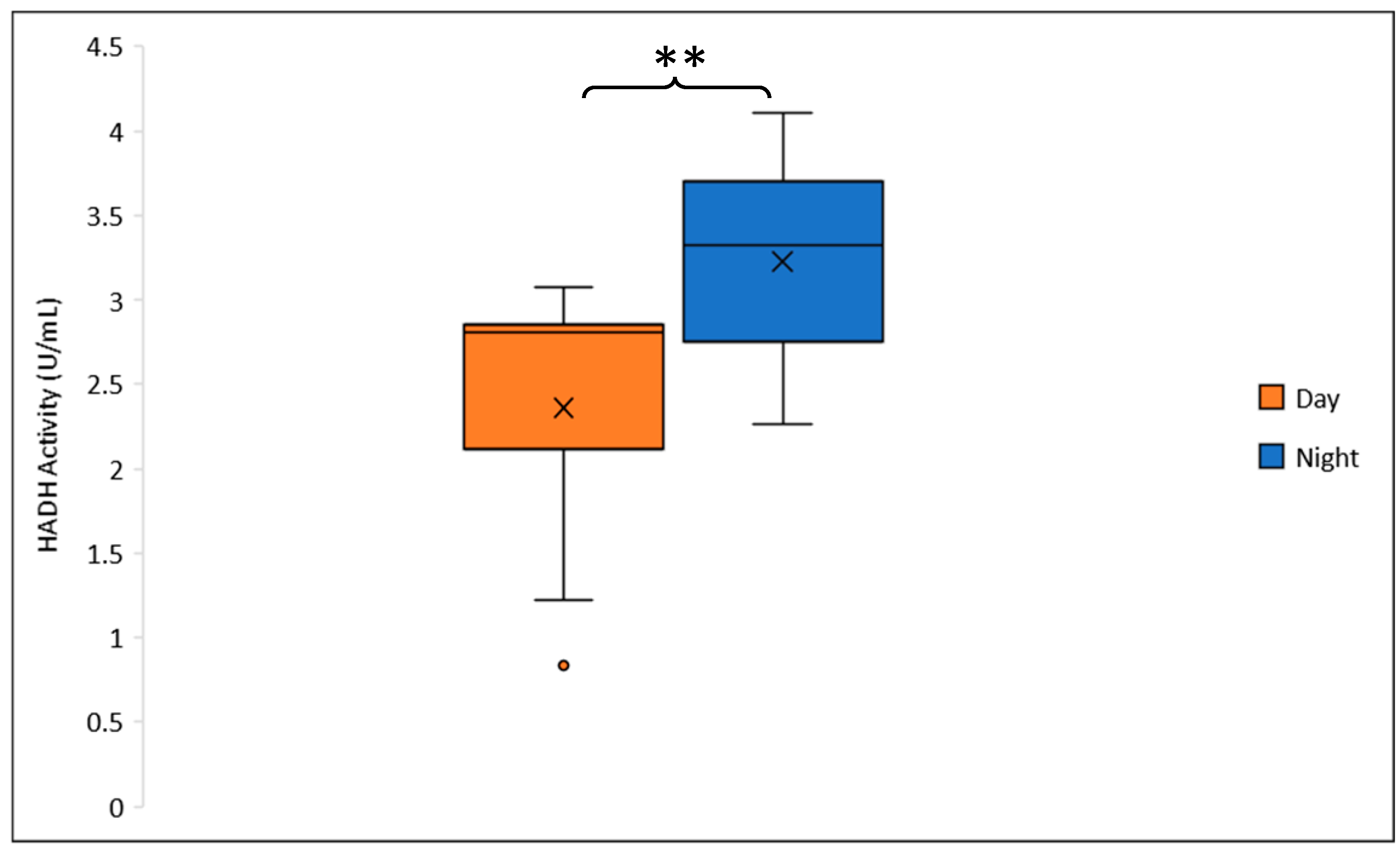

3.2.1. HADH Activity

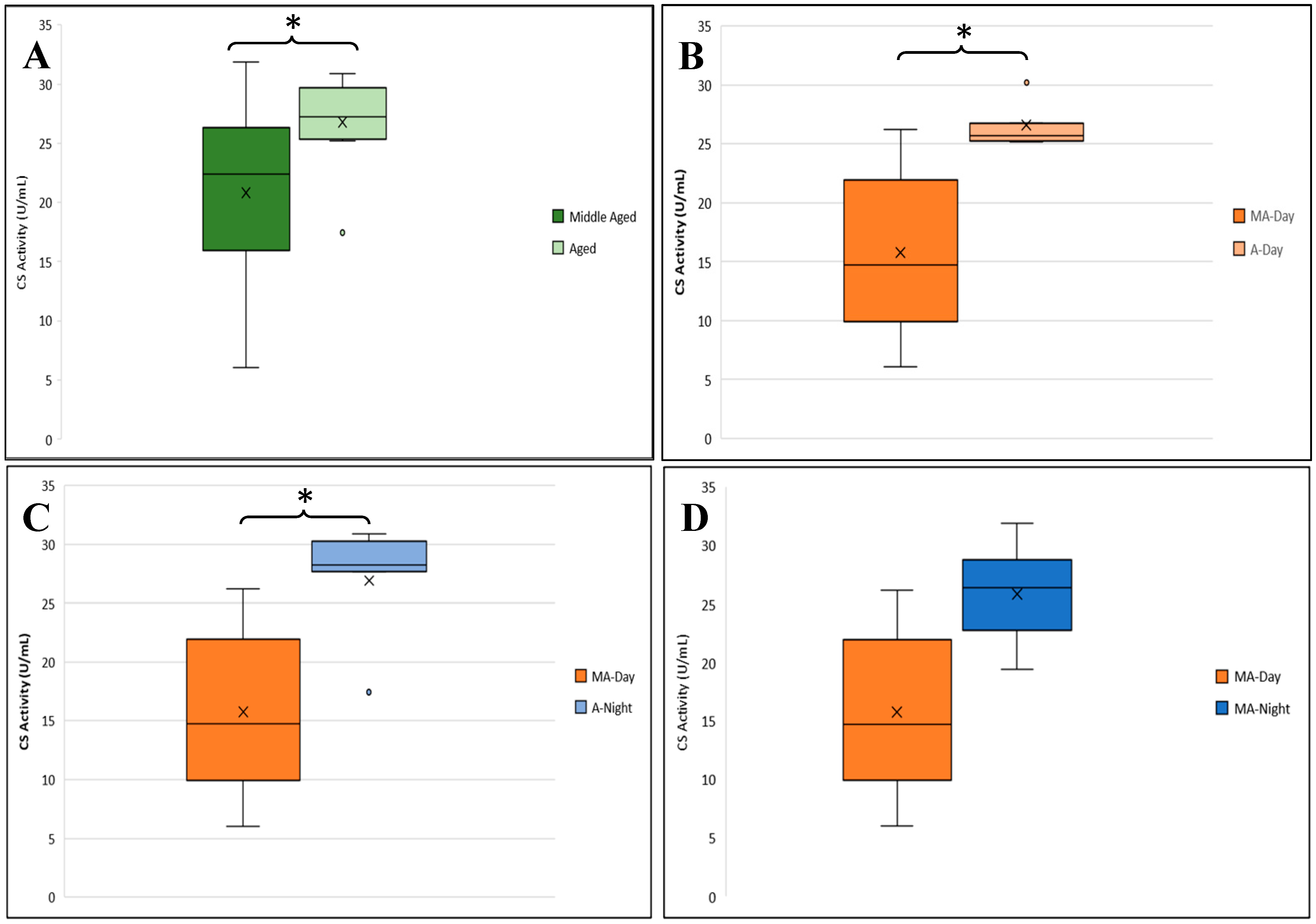

3.2.2. CS Activity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hindle, A.G.; Lawler, J.M.; Campbell, K.L.; Horning, M. Muscle Senescence in Short-lived Wild Mammals, the Soricine Shrews Blarina brevicauda and Sorex palustris. J. Exp. Zool. A Ecol. Genet. Physiol. 2009, 311A, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, S.J. Morphology, Performance and Fitness. Am. Zool. 1983, 23, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.B.; Burt, D.B.; DeWitt, T.J. Form, Function, and Fitness: Pathways to Survival; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Baar, M.P.; Perdiguero, E.; Muñoz-Cánoves, P.; De Keizer, P.L. Musculoskeletal Senescence: A Moving Target Ready to Be Eliminated. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2018, 40, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, J.A.; Baltgalvis, K.A. Interleukin 6 as a Key Regulator of Muscle Mass During Cachexia. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2010, 38, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakelides, H.; Nair, K.S. Sarcopenia of aging and its metabolic impact. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2005, 68, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mu, X.; Tang, Y.; Lu, A.; Takayama, K.; Usas, A.; Wang, B.; Weiss, K.; Huard, J. The Role of Notch Signaling in Muscle Progenitor Cell Depletion and the Rapid Onset of Histopathology in Muscular Dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 2923–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shur, N.F.; Creedon, L.; Skirrow, S.; Atherton, P.J.; MacDonald, I.A.; Lund, J.; Greenhaff, P.L. Age-related changes in muscle architecture and metabolism in humans: The likely contribution of physical inactivity to age-related functional decline. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 68, 101344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Bradley, E.W.; Weivoda, M.M.; Hwang, S.M.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Decklever, T.; Curran, G.L.; Ogrodnik, M.; Jurk, D.; Johnson, K.O.; et al. Transplanted Senescent Cells Induce an Osteoarthritis-Like Condition in Mice. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2016, 72, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedlian, V.R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Chen, X.; Bolt, L.; Tudor, C.; Shen, Z.; Fasouli, E.S.; Prigmore, E.; Kleshchevnikov, V.; et al. Human skeletal muscle aging atlas. Nat. Aging 2024, 4, 727–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseeva, V.; Cisneros, A.; Sica, V.; Deryagin, O.; Lai, Y.; Jung, S.; Andrés, E.; An, J.; Segalés, J.; Ortet, L.; et al. Senescence atlas reveals an aged-like inflamed niche that blunts muscle regeneration. Nature 2023, 613, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Holbrook, C.A.; Hamilton, J.N.; Garoussian, J.; Afshar, M.; Su, S.; Schürch, C.M.; Lee, M.Y.; Goltsev, Y.; Kundaje, A.; et al. A single cell spatial temporal atlas of skeletal muscle reveals cellular neighborhoods that orchestrate regeneration and become disrupted in aging. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-H.; Lee, C.-H.; Lu, L.-S.; Song, I.-W.; Chuang, H.-P.; Kuo, S.-Y.; Wu, J.-Y.; Chen, Y.-T.; Kraus, V.B.; Wu, C.-C.; et al. Direct Assessment of Articular Cartilage and Underlying Subchondral Bone Reveals a Progressive Gene Expression Change in Human Osteoarthritic Knees. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2013, 21, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratzer, R.; Søndergaard, H.B.; Christensen, J.R.; Börnsen, L.; Borup, R.; Sørensen, P.S.; Sellebjerg, F. Gene Expression Analysis of Relapsing–remitting, Primary Progressive and Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2013, 19, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojani, A.; Pungolino, E.; Rossi, G.; D’adda, M.; Bossi, L.E.; Baruzzo, G.; Di Camillo, B.; Perego, A.; Turrini, M.; Elena, C.; et al. Progressive Down Regulation of JAK-STAT, Cell Cycle, and ABC Transporter Genes in CD34+/Lin- Cells of Chronic-Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CP-CML) Patients at Diagnosis Vs. 12 Months of Nilotinib Treatment Vs. Healthy Subjects. Blood 2019, 134, 5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.-H.; Chang, J.-L.; Hua, K.; Huang, W.-C.; Hsu, M.-T.; Chen, Y.-F. Skeletal Muscle in Aged Mice Reveals Extensive Transformation of Muscle Gene Expression. BMC Genetics 2018, 19, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Habiballa, L.; Aversa, Z.; Ng, Y.E.; Sakamoto, A.E.; Englund, D.A.; Pearsall, V.M.; White, T.A.; Robinson, M.M.; Rivas, D.A.; et al. Characterization of cellular senescence in aging skeletal muscle. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Gomez, A.; Buxbaum, J.N.; Petrascheck, M. The aging transcriptome: Read between the lines. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2020, 63, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumasian, R.A.; Harish, A.; Kundu, G.; Yang, J.H.; Ubaida-Mohien, C.; Gonzalez-Freire, M.; Kaileh, M.; Zukley, L.M.; Chia, C.W.; Lyashkov, A.; et al. Skeletal muscle transcriptome in healthy aging. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demontis, F.; Piccirillo, R.; Goldberg, A.L.; Perrimon, N. Mechanisms of Skeletal Muscle Aging: Insights from Drosophila and Mammalian Models. Dis. Models Mech. 2013, 6, 1339–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, T.; Yang, B.; Okazaki, Y.; Yoshizawa, I.; Kajihara, K.; Kato, N.; Wada, M.; Yanaka, N. Time Course Analysis of Skeletal Muscle Pathology of GDE5 Transgenic Mouse. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzibasi, E.; Valenzano, D.R.; Benedetti, M.; Roncaglia, P.; Cattaneo, A.; Domenici, L.; Cellerino, A. Large differences in aging phenotype between strains of the short-lived annual fish Nothobranchius furzeri. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Nam, H.G.; Valenzano, D.R. The short-lived African turquoise killifish: An emerging experimental model for ageing. Dis. Models Mech. 2016, 9, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Fang, Y.; Qu, J.; He, J.; Yi, J.; Chen, R.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, K.; Wu, W.; Sun, D.; et al. Utilizing zebrafish models to elucidate mechanisms and develop therapies for skeletal muscle atrophy. Life Sci. 2025, 362, 123357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, H.; Partridge, L. Invertebrate Models of Age-related Muscle Degeneration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2009, 1790, 1084–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, M.D.W.; Partridge, L. Drosophila as a Model for Ageing. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 2707–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wone, B.W.M.; Kinchen, J.M.; Kaup, E.R.; Wone, B. A Procession of Metabolic Alterations Accompanying Muscle Senescence in Manduca sexta. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wone, B.W.M.; Pathak, J.; Davidowitz, G. Flight duration and flight muscle ultrastructure of unfed hawk moths. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2018, 47, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Yao, S.; Zhai, H.; Liu, C.; Han, J.J. Unraveling aging from transcriptomics. Trends Genet. 2025, 41, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefol, Y.; Korfage, T.; Mjelle, R.; Prebensen, C.; Lüders, T.; Müller, B.; Krokan, H.; Sarno, A.; Alsøe, L.; Consortium Lemonaid; et al. TiSA: TimeSeriesAnalysis-a pipeline for the analysis of longitudinal transcriptomics data. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2023, 5, lqad020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shavlakadze, T.; Morris, M.; Fang, J.; Wang, S.X.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, W.; Tse, H.W.; Mondragon-Gonzalez, R.; Roma, G.; Glass, D.J. Age-Related Gene Expression Signature in Rats Demonstrate Early, Late, and Linear Transcriptional Changes from Multiple Tissues. Cell Reports 2019, 28, 3263–3273.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Descamps, S.; Boutin, S.; Berteaux, D.; Gaillard, J.-M. Best Squirrels Trade a Long Life for an Early Reproduction. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2006, 273, 2369–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershman, A.; Romer, T.G.; Fan, Y.; Razaghi, R.; Smith, W.A.; Timp, W. De Novo Genome Assembly of the Tobacco Hornworm Moth (Manduca sexta). G3 2021, 11, jkaa047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, S.; Huber, W. Differential Expression Analysis for Sequence Count Data. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Society. Ser. B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, M.S.; Dyer, K.; Bracegirdle, J.; Platt, L.; Thomas, M.; Siriett, V.; Kambadur, R.; Sharma, M. Akirin1 (Mighty), a Novel Promyogenic Factor Regulates Muscle Regeneration and Cell Chemotaxis. Exp. Cell. Res. 2009, 315, 2012–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Huang, Z.; Wang, H.; Jia, G.; Liu, G.; Guo, X.; Tang, R.; Long, D. Role of Akirin in Skeletal Myogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 3817–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothakota, S.; Azuma, T.; Reinhard, C.; Klippel, A.; Tang, J.; Chu, K.; McGarry, T.J.; Kirschner, M.W.; Koths, K.; Kwiatkowski, D.J.; et al. Caspase-3-generated fragment of gelsolin: Effector of morphological change in apoptosis. Science 1997, 278, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldt, J.; Schicht, M.; Garreis, F.; Welss, J.; Schneider, U.W.; Paulsen, F. Structure, regulation and related diseases of the actin-binding protein gelsolin. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2018, 20, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Xiang, S.; Cao, J.; Zhu, H.; Yang, B.; He, Q.; Ying, M. Kelch-like proteins: Physiological functions and relationships with diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 148, 104404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, K. Connectin/Titin, Giant Elastic Protein of Muscle. FASEB J. 1997, 11, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granzier, H.L.; Labeit, S. The giant protein titin: A major player in myocardial mechanics, signaling, and disease. Circ. Res. 2004, 94, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loescher, C.M.; Hobbach, A.J.; Linke, W.A. Titin (TTN): From molecule to modifications, mechanics, and medical significance. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 2903–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salcan, S.; Bongardt, S.; Barbosa, D.M.; Efimov, I.R.; Rassaf, T.; Krüger, M.; Kötter, S. Elastic Titin Properties and Protein Quality Control in the Aging Heart. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2020, 1867, 118532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, R. Changes in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism during starvation in adult Manduca sexta. J. Comp. Physiol. B Biochem. Syst. Environ. Physiol. 1991, 161, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrese, E.L.; Flowers, M.T.; Gazard, J.L.; Wells, M.A. Calcium and cAMP are second messengers in the adipokinetic hormone-induced lipolysis of triacylglycerols in Manduca sexta fat body. J. Lipid Res. 1999, 40, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, H.L.; Krumm, K.; Anderson, B.; Christiani, A.; Strait, L.; Li, T.; Irwin, B.; Jiang, S.; Rybachok, A.; Chen, A.; et al. Mouse sarcopenia model reveals sex-and age-specific differences in phenotypic and molecular characteristics. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e172890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroik, D.; Gregorich, Z.R.; Raza, F.; Ge, Y.; Guo, W. Titin: Roles in cardiac function and diseases. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1385821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebrin, I.; Kamzalov, S.; Sohal, R.S. Effects of Age and Caloric Restriction on Glutathione Redox State in Mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003, 35, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebrin, I.; Bayne, A.C.; Mockett, R.J.; Orr, W.C.; Sohal, R.S. Free Aminothiols, Glutathione Redox State and Protein Mixed Disulphides in Aging Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem. J. 2004, 382, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero-Galán, E.; Martínez-Martín, I.; Alegre-Cebollada, J. Redox regulation of protein nanomechanics in health and disease: Lessons from titin. Redox Biol. 2019, 21, 101074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, F.; Hüttemeister, J.; da Silva Lopes, K.; Jüttner, R.; Yu, L.; Bergmann, N.; Friedrich, D.; Preibisch, S.; Wagner, E.; Lehnart, S.E.; et al. Resolving Titin’s Lifecycle and the Spatial Organization of Protein Turnover in Mouse Cardiomyocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 25126–25136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinbara, K.; Sorimachi, H.; Ishiura, S.; Suzuki, K. Muscle-Specific Calpain, P94, Interacts with the Extreme C-Terminal Region of Connectin, a Unique Region Flanked by Two Immunoglobulin C2 Motifs. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1997, 342, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynaud, F.; Fernandez, E.; Coulis, G.; Aubry, L.; Vignon, X.; Bleimling, N.; Gautel, M.; Benyamin, Y.; Ouali, A. Calpain 1-Titin Interactions Concentrate Calpain 1 in the Z-Band Edges and in the N2-Line Region within the Skeletal Myofibril. FEBS J. 2005, 272, 2578–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, A.; Matsushita, K.; Gesellchen, V.; El Chamy, L.; Kuttenkeuler, D.; Takeuchi, O.; Hoffmann, J.A.; Akira, S.; Boutros, M.; Reichhart, J.M. Akirins Are Highly Conserved Nuclear Proteins Required for Nf-Kappab-Dependent Gene Expression in Drosophila and Mice. Nat. Immunol. 2008, 9, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macqueen, D.J.; Johnston, I.A. Evolution of the Multifaceted Eukaryotic Akirin Gene Family. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, A.; Salerno, M.S.; Thomas, M.; Davies, T.; Berry, C.; Dyer, K.; Bracegirdle, J.; Watson, T.; Dziadek, M.; Kambadur, R.; et al. Mighty Is a Novel Promyogenic Factor in Skeletal Myogenesis. Exp. Cell. Res. 2008, 314, 1013–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherron, A.C.; Lawler, A.M.; Lee, S.-J. Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Mass in Mice by a New Tgf-P Superfamily Member. Nature 1997, 387, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobet, L.; Martin, L.J.; Poncelet, D.; Pirottin, D.; Brouwers, B.; Riquet, J.; Schoeberlein, A.; Dunner, S.; Ménissier, F.; Massabanda, J.; et al. A Deletion in the Bovine Myostatin Gene Causes the Double-Muscled Phenotype in Cattle. Nat. Genet. 1997, 17, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambadur, R.; Sharma, M.; Smith, T.P.; Bass, J.J. Mutations in Myostatin (Gdf8) in Double-Muscled Belgian Blue and Piedmontese Cattle. Genome Res. 1997, 7, 910–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Pan, J.S.; Zhang, L. Myostatin suppression of Akirin1 mediates glucocorticoid-induced satellite cell dysfunction. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Hu, S.; Hu, J.; Qiu, J.; Yang, S.; Hu, B.; Gan, X.; Liu, H.; Li, L.; Wang, J. Akirin1 promotes myoblast differentiation by modulating multiple myoblast differentiation factors. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20182152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexell, J.; Taylor, C.C.; Sjöström, M. What Is the Cause of the Ageing Atrophy? Total Number, Size and Proportion of Different Fiber Types Studied in Whole Vastus Lateralis Muscle from 15- to 83-Year-Old Men. J. Neurol. Sci. 1988, 84, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, D.J.; Piasecki, M.; Atherton, P.J. The Age-related Loss of Skeletal Muscle Mass and Function: Measurement and Physiology of Muscle Fibre Atrophy and Muscle Fibre Loss in Humans. Ageing Res. Rev. 2018, 47, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barral, J.M.; Hutagalung, A.H.; Brinker, A.; Hartl, F.U.; Epstein, H.F. Role of the Myosin Assembly Protein Unc-45 as a Molecular Chaperone for Myosin. Science 2002, 295, 669–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiesch, P.C.; Kim, J.; Mouysset, J.; Barikbin, R.; Lochmüller, H.; Cassata, G.; Krause, S.; Hoppe, T. The Ubiquitin-Selective Chaperone Cdc-48/P97 Links Myosin Assembly to Human Myopathy. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafez, N.; El-Awadly, Z.M.; Arafa, R.K. UCH-L3 structure and function: Insights about a promising drug target. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 227, 113970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshaies, R.J.; Joazeiro, C.A. RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009, 78, 399–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setsuie, R.; Sakurai, M.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Wada, K. Ubiquitin Dimers Control the Hydrolase Activity of Uch-L3. Neurochem. Int. 2009, 54, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamura, T.; Koepp, D.M.; Conrad, M.N.; Skowyra, D.; Moreland, R.J.; Iliopoulos, O.; Lane, W.S.; Kaelin, W.G., Jr.; Elledge, S.J.; Conaway, R.C.; et al. Rbx1, a Component of the Vhl Tumor Suppressor Complex and Scf Ubiquitin Ligase. Science 1999, 284, 657–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.Q.; Kentsis, A.; Dias, D.C.; Yamoah, K.; Wu, K. Nedd8 on Cullin: Building an Expressway to Protein Destruction. Oncogene 2004, 23, 1985–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroski, M.D.; Deshaies, R.J. Function and Regulation of Cullin–Ring Ubiquitin Ligases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatar, M.; Khazaeli, A.A.; Curtsinger, J.W. Chaperoning Extended Life. Nature 1997, 390, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.C.; Bohmann, D.; Jasper, H. Jnk Signaling Confers Tolerance to Oxidative Stress and Extends Lifespan in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 2003, 5, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosslau, A.; Ruoff, P.; Mohsenzadeh, S.; Hobohm, U.; Rensing, L. Heat Shock and Oxidative Stress-Induced Exposure of Hydrophobic Protein Domains as Common Signal in the Induction of Hsp68. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 1814–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelens, W.C. Cell Biological Roles of Ab-Crystallin. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2014, 115, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimauro, I.; Antonioni, A.; Mercatelli, N.; Caporossi, D. The Role of Ab-Crystallin in Skeletal and Cardiac Muscle Tissues. Cell Stress Chaperones 2018, 23, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornell, E.; Aquilina, A. Regulation of Aa- and Ab-Crystallins Via Phosphorylation in Cellular Homeostasis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 4127–4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bigio, M.R.; Chudley, A.E.; Sarnat, H.B.; Campbell, C.; Goobie, S.; Chodirker, B.N.; Selcen, D. Infantile Muscular Dystrophy in Canadian Aboriginals Is an Ab-Crystallinopathy. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 69, 866–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selcen, D.; Engel, A.G. Myofibrillar Myopathy Caused by Novel Dominant Negative Alpha B-Crystallin Mutations. Ann. Neurol. 2003, 54, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, K.M.; Al-Sarraj, S.; Sewry, C.; Buk, S.; Tan, S.V.; Pitt, M.; Durward, A.; McDougall, M.; Irving, M.; Hanna, M.G.; et al. Infantile Onset Myofibrillar Myopathy Due to Recessive Cryab Mutations. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2011, 21, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichna, J.P.; Potulska-Chromik, A.; Miszta, P.; Redowicz, M.J.; Kaminska, A.M.; Zekanowski, C.; Filipek, S. A Novel Dominant D109a Cryab Mutation in a Family with Myofibrillar Myopathy Affects Ab-Crystallin Structure. BBA Clin. 2017, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, N.; Hayashi, T.; Arimura, T.; Koga, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Shibata, H.; Teraoka, K.; Chikamori, T.; Yamashina, A.; Kimura, A. Alpha B-Crystallin Mutation in Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 342, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilotto, A.; Marziliano, N.; Pasotti, M.; Grasso, M.; Costante, A.M.; Arbustini, E. Alphab-Crystallin Mutation in Dilated Cardiomyopathies: Low Prevalence in a Consecutive Series of 200 Unrelated Probands. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 346, 1115–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runtuwene, L.R.; Kawashima, S.; Pijoh, V.D.; Tuda, J.S.B.; Hayashida, K.; Yamagishi, J.; Sugimoto, C.; Nishiyama, S.; Sasaki, M.; Orba, Y.; et al. The Lethal(2)-Essential-for-Life [L(2)Efl] Gene Family Modulates Dengue Virus Infection in Aedes Aegypti. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtkooper, R.H.; Argmann, C.; Houten, S.M.; Cantó, C.; Jeninga, E.H.; Andreux, P.A.; Thomas, C.; Doenlen, R.; Schoonjans, K.; Auwerx, J. The Metabolic Footprint of Aging in Mice. Sci. Rep. 2011, 1, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazelzadeh, P.; Hangelbroek, R.W.; Tieland, M.; de Groot, L.C.; Verdijk, L.B.; van Loon, L.J.; Smilde, A.K.; Alves, R.D.; Vervoort, J.; Müller, M.; et al. The Muscle Metabolome Differs between Healthy and Frail Older Adults. J. Proteome Res. 2016, 15, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrese, E.L.; Soulages, J.L. Insect Fat Body: Energy, Metabolism, and Regulation. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2010, 55, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Salhy, M.; Falkmer, S.; Kramer, K.J.; Speirs, R.D. Immunocytochemical Evidence for the Occurrence of Insulin in the Frontal Ganglion of a Lepidopteran Insect, the Tobacco Hornworm Moth, Manduca sexta L. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1984, 54, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Brown, M.R. Signaling and function of insulin-like peptides in insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2006, 51, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badisco, L.; Van Wielendaele, P.; Vanden Broeck, J. Eat to Reproduce: A Key Role for the Insulin Signaling Pathway in Adult Insects. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, W.S.; Tatar, M. Juvenile Hormone Regulation of Longevity in the Migratory Monarch Butterfly. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2001, 268, 2509–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatar, M.; Kopelman, A.; Epstein, D.; Tu, M.P.; Yin, C.M.; Garofalo, R.S. A Mutant Drosophila Insulin Receptor Homolog That Extends Life-Span and Impairs Neuroendocrine Function. Science 2001, 292, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatar, M. The Neuroendocrine Regulation of Drosophila Aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2004, 39, 1745–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, P.; Bhuju, S.; Thapa, N.; Bhattarai, H.K. ATP synthase: Structure, function and inhibition. Biomol. Concepts 2019, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.Z.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Z.B. Mitochondrial electron transport chain, ROS generation and uncoupling. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legan, S.K.; Rebrin, I.; Mockett, R.J.; Radyuk, S.N.; Klichko, V.I.; Sohal, R.S.; Orr, W.C. Overexpression of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase extends the life span of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 32492–32499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radyuk, S.N.; Michalak, K.; Klichko, V.I.; Benes, J.; Rebrin, I.; Sohal, R.S.; Orr, W.C. Peroxiredoxin 5 confers protection against oxidative stress and apoptosis and also promotes longevity in Drosophila. Biochem. J. 2009, 419, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mockett, R.J.; Sohal, R.S.; Orr, W.C. Overexpression of glutathione reductase extends survival in transgenic Drosophila melanogaster under hyperoxia but not normoxia. FASEB J. 1999, 13, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchitomi, R.; Hatazawa, Y.; Senoo, N.; Yoshioka, K.; Fujita, M.; Shimizu, T.; Miura, S.; Ono, Y.; Kamei, Y. Metabolomic analysis of skeletal muscle in aged mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschenes, M.R. Effects of aging on muscle fibre type and size. Sports Med. 2004, 34, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloney, E.B.; de Winter, F.; Verhaagen, J. ALS as a distal axonopathy: Molecular mechanisms affecting neuromuscular junction stability in the presymptomatic stages of the disease. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tintignac, L.A.; Brenner, H.R.; Rüegg, M.A. Mechanisms regulating neuromuscular junction development and function and causes of muscle wasting. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 809–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Dominguez, B.; Yang, J.; Aryal, P.; Brandon, E.P.; Gage, F.H.; Lee, K.F. Neurotransmitter acetylcholine negatively regulates neuromuscular synapse formation by a Cdk5-dependent mechanism. Neuron 2005, 46, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misgeld, T.; Kummer, T.T.; Lichtman, J.W.; Sanes, J.R. Agrin promotes synaptic differentiation by counteracting an inhibitory effect of neurotransmitter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 11088–11093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, M.C.; Lin, W.; Yang, J.; Dominguez, B.; Padgett, D.; Sugiura, Y.; Aryal, P.; Gould, T.W.; Oppenheim, R.W.; Hester, M.E. Acetylcholine negatively regulates development of the neuromuscular junction through distinct cellular mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 10702–10707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, S.K.; Sutherland, N.M.; Valdez, G. Attenuating cholinergic transmission increases the number of satellite cells and preserves muscle mass in old age. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugita, S.; Fleming, L.L.; Wood, C.; Vaughan, S.K.; Gomes, M.P.; Camargo, W.; Naves, L.A.; Prado, V.F.; Prado, M.A.M.; Guatimosim, C. VAChT overexpression increases acetylcholine at the synaptic cleft and accelerates aging of neuromuscular junctions. Skelet. Muscle 2016, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuda, T.; Haga, T. High-affinity choline transporter. Neurochem. Res. 2003, 28, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, F.M.; Black, S.A.; Prado, V.F.; Rylett, R.J.; Ferguson, S.S.; Prado, M.A. The “ins” and “outs” of the high-affinity choline transporter CHT1. J. Neurochem. 2006, 97, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, B. Temperature regulation of the Sphinx moth, Manduca sexta: I. flight energetics and body temperature during free and tethered flight. J. Exp. Biol. 1971, 54, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmsen, S.M.; Dzialowski, E. Substrate use and temperature effects in flight muscle mitochondria from an endothermic insect, the hawkmoth Manduca sexta. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2023, 281, 111439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sex | Age Class | Sample Day (Post-Eclosion) | Diel Time and Age Sampling (D-Day and N-Night) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Middle Age | Day 2 (D2) | D2, N2, D3, N3, D4, N4, D5, N5 |

| Advanced Age | Day 5 (D5) | ||

| Female | Middle Age | Day 4 (D4) | D4, N4, D5, N5, D6, N6, D7, N7 |

| Advanced Age | Day 7 (D7) |

| Variable | Symbol | Value/Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Total Reaction Volume | V | 0.2 mL |

| Dilution Factor | dil | 11 |

| Light Path | d | 0.67 cm |

| Volume of Homogenate | a | 0.002 mL |

| Molar Extinction Coefficient (CS) | ϵ | 13.6 mM−1 cm−1 (TNB at 412 nm) |

| Molar Extinction Coefficient (HADH) | ϵ | 6.22 mM−1 cm−1 (NADH at 340 nm) |

| Sample Absorbance (CS) | Absorbance (412 nm) minus background | |

| Sample Absorbance (HADH) | Absorbance (340 nm) minus background |

| Sex | Raw Reads | Clean Reads | Mapping Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 1,501,272,784 | 1,424,653,808 | 84.6 |

| Female | 1,520,863,862 | 1,437,381,790 | 87.2 |

| Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| Akirin | 5′–TTATGTTTCCCCACCTGTCTG | 5′–GAACACAATTATCCAGCGAACC |

| Gelsolin | 5′–TACATTCTGGACACGGGAAG | 5′–TGAAACGTGTACCCAGTTAGG |

| Kelch | 5′–TTC CTT GCT GTT CTC CCATAG | 5′–AGTCCAAGTGTTTGTCCGTG |

| Titin | 5′–TGAACCCTATTGAGTCTTGCTG | 5′–GTGGCCTGACATGAAGTCTAG |

| Actin | 5′–GCCAGAAAGACTCCTACGTTG | 5′–TTCTCCATGTCATCCCAGTTG |

| Pathway | Gene Name | log2 FC |

|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acid β-Oxidation | Trifunctional enzyme subunit alpha | −3.6287 |

| Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase B | −2.4069 | |

| Hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase | −2.3855 | |

| 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase | −1.6528 | |

| Probable enoyl-CoA hydratase | −1.3494 | |

| Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle | Fumarate hydratase | −1.7915 |

| Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein subunit | −1.7434 | |

| Succinate-CoA ligase [ADP-forming] subunit beta | −1.7418 | |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 subunit alpha | −1.7222 | |

| Malate dehydrogenase | −1.5403 | |

| Citrate synthase 2 | −1.4439 | |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 subunit beta | −1.3942 | |

| Amino Acid Metabolism | 2-oxoisovalerate dehydrogenase subunit beta | 1.0183 |

| Methylcrotonoyl-CoA carboxylase beta chain | −1.8970 | |

| Oxidative Phosphorylation | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 75 kDa subunit | −8.7794 |

| and Electron Transport Chain | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 6 | −1.7617 |

| NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 3 | −1.5022 | |

| NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 49 kDa subunit | −1.2090 | |

| Mitochondrial ATP synthase lipid binding protein | −1.7005 | |

| ATP synthase subunit O | −1.6296 | |

| ATP synthase subunit gamma | −1.5387 | |

| ATP synthase subunit alpha | −1.3979 | |

| ATP synthase subunit beta | −1.3196 | |

| ATP synthase subunit d | −1.2778 | |

| Cytochrome c1-2 heme protein | −1.6630 | |

| Cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 6 | −1.3565 | |

| Cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 2 | −1.3125 | |

| Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 4 isoform 1 | −1.3512 | |

| Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 5B | −1.2896 | |

| Ubiquitin-Dependent Catabolism | Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase isoenzyme L3 | 2.0267 |

| Ubiquitin recognition factor in ER-associated degradation protein 1 | 1.7568 | |

| Ubiquitin conjugation factor E4 B | 1.6352 | |

| Cullin-2 | 1.1491 | |

| Ubiquilin-1 | 1.0763 | |

| E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase siah2 | −1.6271 | |

| Proteasome-Mediated Catabolism | Proteasome subunit alpha type 2 | 2.0653 |

| Proteasome subunit alpha type 7-1 | 2.0596 | |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 8 | 1.8423 | |

| Proteasome subunit alpha type 3 | 1.8211 | |

| Proteasome subunit beta type 1 | 1.8012 | |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 7 | 1.7898 | |

| 26S proteasome regulatory subunit 8-like | 1.7408 | |

| Proteasome subunit beta type 4 | 1.7372 | |

| Proteasome subunit alpha type 1 | 1.7322 | |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 13 | 1.6819 | |

| 26S proteasome regulatory subunit 10B | 1.6822 | |

| Proteasome subunit alpha type 4 | 1.6678 | |

| UV excision repair protein RAD23 homolog A | 1.6409 | |

| 26S proteasome regulatory subunit 7 | 1.6159 | |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 1 | 1.599 | |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 6 | 1.5746 | |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 2 | 1.5629 | |

| 26S proteasome regulatory subunit 6A-B | 1.536 | |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 12 | 1.5142 | |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 11 | 1.5134 | |

| Peptide-N(4)-(N-acetyl-β-glucosaminyl)asparagine amidase | 1.3655 | |

| Heat Shock Proteins | αB-crystallin | −3.3083 |

| Hsp68 (transcript 1) | −3.1492 | |

| Hsp68 (transcript 2) | −1.971 | |

| Lethal(2)-essential-for-life (l(2)efl) (7 transcripts) | −2.5424 to −1.7951 | |

| Oxidative Stress Response | Glutathione S-transferase 2-like | 2.0604 |

| Muscle mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD) | −1.8147 | |

| Glutathione S-transferase 1-like | −1.0967 | |

| Muscle Structure | Titin (transcript 1) | 2.6626 |

| Titin (transcript 2) | 1.5671 | |

| Akirin | 1.3076 | |

| Other | Insulin receptor | 1.4861 |

| Glucosamine-6-phosphate isomerase | 1.4339 |

| Age Comparison | Pathway | Gene Name | log2 FC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age 2 vs. Age 3 | Cellular Signaling | sodium- and chloride-dependent GABA transporter 1 | 2.3224 |

| sodium channel protein para | 2.2053 | ||

| sodium/potassium/calcium exchanger 4 | 2.0749 | ||

| vesicular acetylcholine transporter | 2.0226 | ||

| sodium/potassium/calcium exchanger Nckx30C | 1.9863 | ||

| potassium voltage-gated channel unc-103 | 1.8663 | ||

| sodium/hydrogen exchanger 3 | 1.7188 | ||

| glycine receptor subunit alpha-4 | 1.6832 | ||

| high-affinity choline transporter 1 | 1.6273 | ||

| glutamate receptor 1 | 1.536 | ||

| GABA receptor subunit beta | 1.5138 | ||

| sodium/calcium exchanger 1 | 1.3743 | ||

| Carbohydrate Metabolism | Facilitated trehalose transporter Tret1 (transcript 1) | 2.1610 | |

| Facilitated trehalose transporter Tret1 (transcript 2) | 2.1029 | ||

| Age 3 vs. Age 4 | Calcium Signaling | Ryanodine Receptor | −1.3605 |

| Gene Name | log2 FC |

|---|---|

| Alsin | −1.7704 |

| Sodium/hydrogen exchanger 3 | −1.7424 |

| Phosphate carrier protein | −1.327 |

| Facilitated trehalose transporter | −1.1802 |

| Ornithine decarboxylase | −1.1467 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Del Grosso, A.; Wone, B.; McMahon, C.; Downs, H.; Wone, B.W.M. Gene Expression Dynamics Underlying Muscle Aging in the Hawk Moth Manduca sexta. Genes 2025, 16, 1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111306

Del Grosso A, Wone B, McMahon C, Downs H, Wone BWM. Gene Expression Dynamics Underlying Muscle Aging in the Hawk Moth Manduca sexta. Genes. 2025; 16(11):1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111306

Chicago/Turabian StyleDel Grosso, Avery, Beate Wone, Connor McMahon, Hallie Downs, and Bernard W. M. Wone. 2025. "Gene Expression Dynamics Underlying Muscle Aging in the Hawk Moth Manduca sexta" Genes 16, no. 11: 1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111306

APA StyleDel Grosso, A., Wone, B., McMahon, C., Downs, H., & Wone, B. W. M. (2025). Gene Expression Dynamics Underlying Muscle Aging in the Hawk Moth Manduca sexta. Genes, 16(11), 1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111306