Genome-Wide Analysis Unveils the Evolutionary Impact of Allopolyploidization on the 14-3-3 Gene Family in Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of 14-3-3 Members

2.2. Chromosomal Location, Gene Duplication, and Syntenic Analysis

2.3. Characterization of 14-3-3 Proteins

2.4. Phylogenetic Tree Construction and Analysis

2.5. Gene Structure and Motif Identification

2.6. Prediction of Cis-Acting Elements

2.7. Analysis of Gene Expression

3. Results

3.1. Identification of 14-3-3 Genes

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of 14-3-3 Gene Families

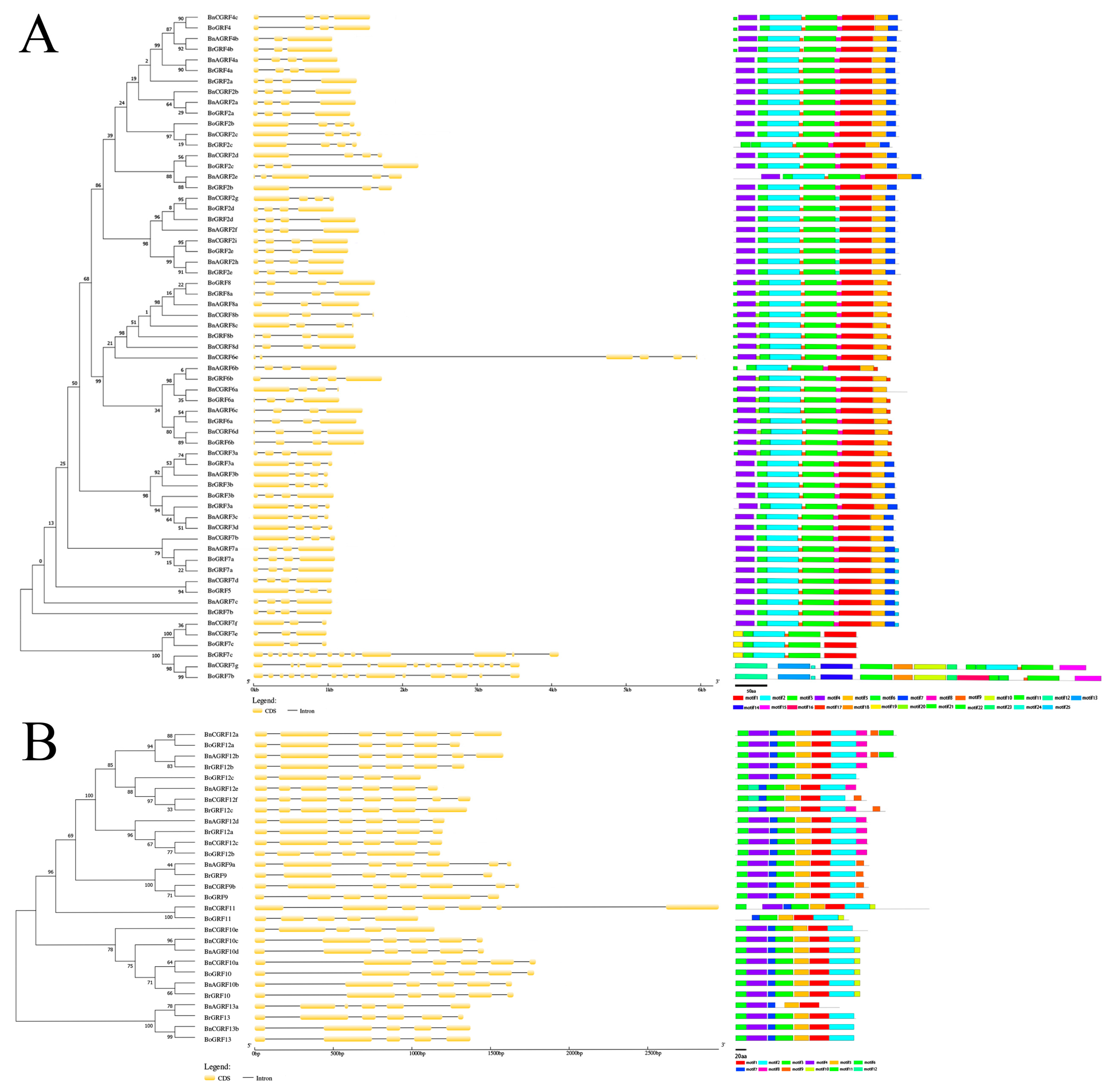

3.3. Gene Structure and Motif Analysis

3.4. Synteny and Duplicated Gene Analysis of 14-3-3 Genes

3.5. Prediction of Physicochemical Properties of 14-3-3 Proteins

3.6. Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements in 14-3-3 Genes

3.7. Expression Patterns of 14-3-3 Genes in Different Tissues

4. Discussion

4.1. Allopolyploidization as a Driver of Gene Family Expansion

4.2. Polyploidization Drives Regulatory Pattern Diversification

4.3. Polyploidization Drives Structural and Biochemical Adaptation of 14-3-3 Proteins

4.4. Polyploidization Drives Diversification of Expression Patterns

4.5. Evolutionary Implications and Future Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| B. napus | Brassica napus |

| B. rapa | Brassica rapa |

| B. oleracea | Brassica oleracea |

| A. thaliana | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| GRFs | G-box binding regulators |

| MW | Molecular weight |

| GRAVY | Grand average of hydropathicity |

| II | Instability index |

| pI | Isoelectric point |

| MYA | Million years ago |

References

- Otto, S.P.; Whitton, J. Polyploid incidence and evolution. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2000, 34, 401–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayrose, I.; Barker, M.S.; Otto, S.P. Probabilistic models of chromosome number evolution and the inference of polyploidy. Syst. Biol. 2010, 59, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Peer, Y.; Mizrachi, E.; Marchal, K. The evolutionary significance of polyploidy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017, 18, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lin, F.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, S.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Li, G.; Lin, X.; Wang, X.; et al. Genomic mosaicism due to homoeologous exchange generates extensive phenotypic diversity in nascent allopolyploids. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2021, 8, nwaa277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltis, P.S.; Marchant, D.B.; Van de Peer, Y.; Soltis, D.E. Polyploidy and genome evolution in plants. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2015, 35, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayale, A.; Parisod, C. Natural pathways to polyploidy in plants and consequences for genome reorganization. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2013, 140, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman-Minkov, A.; Sabath, N.; Mayrose, I. Whole-genome duplication as a key factor in crop domestication. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 16115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarrow, M.; Wang, Y.; Sun, G. Molecular regulatory mechanisms underlying the adaptability of polyploid plants. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2021, 96, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLille, J.M.; Sehnke, P.C.; Ferl, R.J. The arabidopsis 14-3-3 family of signaling regulators. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenquist, M.; Alsterfjord, M.; Larsson, C.; Sommarin, M. Data mining the Arabidopsis genome reveals fifteen 14-3-3 genes. Expression is demonstrated for two out of five novel genes. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferl, R.J.; Manak, M.S.; Reyes, M.F. The 14-3-3s. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, REVIEWS3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camoni, L.; Visconti, S.; Aducci, P.; Marra, M. 14-3-3 Proteins in Plant Hormone Signaling: Doing Several Things at Once. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, N.; Lu, D.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.-X.; Ma, H.; Wang, X. Dual role of BKI1 and 14-3-3s in brassinosteroid signaling to link receptor with transcription factors. Dev. Cell. 2011, 21, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Hayashi, K.; Kinoshita, T. Auxin activates the plasma membrane H+-ATPase by phosphorylation during hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2012, 159, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Nakata, M.; Fukazawa, J.; Ishida, S.; Takahashi, Y. Scaffold Function of Ca2+-Dependent Protein Kinase: Tobacco Ca2+-DEPENDENT PROTEIN KINASE1 Transfers 14-3-3 to the Substrate REPRESSION OF SHOOT GROWTH after Phosphorylation. Plant Physiol. 2014, 165, 1737–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, W.; Coleman, M.; Orgil, U.; Feng, J.; Ma, X.; Ferl, R.; Turner, J.G.; Xiao, S. Arabidopsis 14-3-3 lambda is a positive regulator of RPW8-mediated disease resistance. Plant J. 2009, 60, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taoka, K.-I.; Ohki, I.; Tsuji, H.; Furuita, K.; Hayashi, K.; Yanase, T.; Yamaguchi, M.; Nakashima, C.; Purwestri, Y.A.; Tamaki, S.; et al. 14-3-3 proteins act as intracellular receptors for rice Hd3a florigen. Nature 2011, 476, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko-Suzuki, M.; Kurihara-Ishikawa, R.; Okushita-Terakawa, C.; Kojima, C.; Nagano-Fujiwara, M.; Ohki, I.; Tsuji, H.; Shimamoto, K.; Taoka, K.-I. TFL1-Like Proteins in Rice Antagonize Rice FT-Like Protein in Inflorescence Development by Competition for Complex Formation with 14-3-3 and FD. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, J.D.; Folta, K.M.; Paul, A.L.; Ferl, R.J. The 14-3-3 Proteins mu and upsilon influence transition to flowering and early phytochrome response. Plant Physiol. 2007, 145, 1692–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, J.D.; Paul, A.L.; Ferl, R.J. The 14-3-3 proteins of Arabidopsis regulate root growth and chloroplast development as components of the photosensory system. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 3061–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Li, Q.; Sun, L.; He, Z. The rice 14-3-3 gene family and its involvement in responses to biotic and abiotic stress. DNA Res. 2006, 13, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ling, L.; Jiang, Z.; Tan, W.; Liu, Z.; Wu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, S.; Ma, J.; Wang, G.; et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the 14-3-3 gene family in soybean (Glycine max). PeerJ 2019, 7, e7950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Chen, W.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, X.; Jin, Y.; Zhan, C.; Liu, G.; Liu, X.; Ma, D.; Qiao, Y. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of Wheat 14-3-3 Genes Unravels the Role of TaGRF6-A in Salt Stress Tolerance by Binding MYB Transcription Factor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Wang, Y.; Chai, F.; Li, S.; Xin, H.; Liang, Z. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the 14-3-3 family in Vitis vinifera L. during berry development and cold- and heat-stress response. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 579. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Luo, X.; Sun, M.; Chen, C.; Ding, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, S.; Yu, Q.; Jia, B.; Ji, W.; et al. A Glycine soja 14-3-3 protein GsGF14o participates in stomatal and root hair development and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; He, C.; Wang, J.; Mao, Z.; Holaday, S.A.; Allen, R.D.; Zhang, H. Overexpression of the Arabidopsis 14-3-3 protein GF14 lambda in cotton leads to a "stay-green" phenotype and improves stress tolerance under moderate drought conditions. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004, 45, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalá, R.; López-Cobollo, R.; Castellano, M.M.; Angosto, T.; Alonso, J.M.; Ecker, J.R.; Salinas, J. The Arabidopsis 14-3-3 protein RARE COLD INDUCIBLE 1A links low-temperature response and ethylene biosynthesis to regulate freezing tolerance and cold acclimation. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 3326–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Cheng, L.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, H.; Lu, D.; Shen, C. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the 14-3-3 Family Genes in Medicago truncatula. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalhoub, B.; Denoeud, F.; Liu, S.; Parkin, I.A.P.; Tang, H.; Wang, X.; Chiquet, J.; Belcram, H.; Tong, C.; Samans, B.; et al. Plant genetics. Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science 2014, 345, 950–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Guan, P.; Zhao, L.; Ma, M.; Xie, L.; Li, Y.; Zheng, R.; Ouyang, W.; Wang, S.; Li, H.; et al. Asymmetric epigenome maps of subgenomes reveal imbalanced transcription and distinct evolutionary trends in Brassica napus. Mol. Plant. 2021, 14, 604–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brassica rapa Genome Sequencing Project Consortium; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Sun, R.; Wu, J.; Liu, S.; Bai, Y.; Mun, J.H.; Bancroft, I.; et al. The genome of the mesopolyploid crop species Brassica rapa. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 1035–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Tong, C.; Edwards, D.; Parkin, I.A.P.; Zhao, M.; Ma, J.; Yu, J.; Huang, S.; et al. The Brassica oleracea genome reveals the asymmetrical evolution of polyploid genomes. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, T.; He, X.; Cai, X.; Lin, R.; Liang, J.; Wu, J.; King, G.; Wang, X. BRAD V3.0: An upgraded Brassicaceae database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D1432–D1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A "one for all, all for one" bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant. 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; I Hurwitz, D.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; et al. CDD/SPARCLE: The conserved domain database in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D265–D268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Chuguransky, S.; Williams, L.; Qureshi, M.; Salazar, G.A.; Sonnhammer, E.L.L.; Tosatto, S.C.; Paladin, L.; Raj, S.; Richardson, L.J.; et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D412–D419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Khedkar, S.; Bork, P. SMART: Recent updates, new developments and status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D458–D460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Lv, W.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, D.; Cai, G.; Pan, J.; Li, D. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of calcium-dependent protein kinase in maize. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywinski, M.; Schein, J.; Birol, I.; Connors, J.; Gascoyne, R.; Horsman, D.; Jones, S.J.; Marra, M.A. Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1639–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artimo, P.; Jonnalagedda, M.; Arnold, K.; Baratin, D.; Csardi, G.; de Castro, E.; Duvaud, S.; Flegel, V.; Fortier, A.; Gasteiger, E.; et al. ExPASy: SIB bioinformatics resource portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W597–W603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: An online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W242–W245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, R.; Wu, X.; Wang, J. Homoeolog expression bias and expression level dominance (ELD) in four tissues of natural allotetraploid Brassica napus. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wan, N.; Cheng, Z.; Mo, Y.; Liu, B.; Liu, H.; Raboanatahiry, N.; Yin, Y.; Li, M. Whole-Genome Identification and Expression Pattern of the Vicinal Oxygen Chelate Family in Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.; Conery, J.S. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science 2000, 290, 1151–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulin, A.; Auer, P.L.; Libault, M.; Schlueter, J.; Farmer, A.; May, G.; Stacey, G.; Doerge, R.W.; Jackson, S.A. The fate of duplicated genes in a polyploid plant genome. Plant J. 2013, 73, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, R.; Liu, Z.; Wu, X.; Wang, J. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the WUSCHEL-related homeobox (WOX) gene family in allotetraploid Brassica napus reveals changes in WOX genes during polyploidization. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, R.; Liang, Z.; Wu, X.; Wang, J. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the EIN3/EIL gene family in allotetraploid Brassica napus reveal its potential advantages during polyploidization. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Ho, T.H. Functional dissection of an abscisic acid (ABA)-inducible gene reveals two independent ABA-responsive complexes each containing a G-box and a novel cis-acting element. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 295–307. [Google Scholar]

- Nuruzzaman, M.; Sharoni, A.M.; Satoh, K.; Kumar, A.; Leung, H.; Kikuchi, S. Comparative transcriptome profiles of the WRKY gene family under control, hormone-treated, and drought conditions in near-isogenic rice lines reveal differential, tissue specific gene activation. J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 171, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, A.; Voigt, G.; Faure, A.J.; Lehner, B. Genetics, energetics, and allostery in proteins with randomized cores and surfaces. Science 2025, 389, eadq3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhouse, M.R.; Cheng, F.; Pires, J.C.; Lisch, D.; Freeling, M.; Wang, X. Origin, inheritance, and gene regulatory consequences of genome dominance in polyploids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 5283–5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Duplicated Gene Pairs | Ka | Ks | Ka/Ks | Duplication Type | Types of Selection | Time (MYA) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BrGRF2a | vs. | BrGRF2b | 0.0208 | 0.3966 | 0.052446 | Segmental | Purify selection | 13.22 |

| BrGRF2a | vs. | BrGRF2c | 0.0215 | 0.3535 | 0.06082 | Segmental | Purify selection | 11.78333 |

| BrGRF2b | vs. | BrGRF2c | 0.0316 | 0.3394 | 0.093105 | Segmental | Purify selection | 11.31333 |

| BrGRF2d | vs. | BrGRF2e | 0.0495 | 0.4794 | 0.103254 | Segmental | Purify selection | 15.98 |

| BrGRF3a | vs. | BrGRF3b | 0.0245 | 0.4011 | 0.061082 | Segmental | Purify selection | 13.37 |

| BrGRF4a | vs. | BrGRF4b | 0.034 | 0.3114 | 0.109184 | Segmental | Purify selection | 10.38 |

| BrGRF6a | vs. | BrGRF6b | 0.0559 | 0.3705 | 0.150877 | Segmental | Purify selection | 12.35 |

| BrGRF7a | vs. | BrGRF7b | 0.0175 | 0.3308 | 0.052902 | Segmental | Purify selection | 11.02667 |

| BrGRF8a | vs. | BrGRF8b | 0.0177 | 0.4204 | 0.042103 | Segmental | Purify selection | 14.01333 |

| BrGRF12a | vs. | BrGRF12b | 0.0265 | 0.3298 | 0.080352 | Segmental | Purify selection | 10.99333 |

| BrGRF12a | vs. | BrGRF12c | 0.0468 | 0.2898 | 0.161491 | Segmental | Purify selection | 9.66 |

| BrGRF12b | vs. | BrGRF12c | 0.0327 | 0.3236 | 0.101051 | Segmental | Purify selection | 10.78667 |

| BoGRF2a | vs. | BoGRF2b | 0.0176 | 0.3443 | 0.051118 | Segmental | Purify selection | 11.47667 |

| BoGRF2a | vs. | BoGRF2c | 0.0229 | 0.4037 | 0.056725 | Segmental | Purify selection | 13.45667 |

| BoGRF2b | vs. | BoGRF2c | 0.0321 | 0.3123 | 0.102786 | Segmental | Purify selection | 10.41 |

| BoGRF2d | vs. | BoGRF2e | 0.0523 | 0.5017 | 0.104246 | Segmental | Purify selection | 16.72333 |

| BoGRF3a | vs. | BoGRF3b | 0.0244 | 0.3522 | 0.069279 | Segmental | Purify selection | 11.74 |

| BoGRF5 | vs. | BoGRF7a | 0.0192 | 0.3223 | 0.059572 | Segmental | Purify selection | 10.74333 |

| BoGRF6a | vs. | BoGRF6b | 0.0302 | 0.422 | 0.071564 | Segmental | Purify selection | 14.06667 |

| BoGRF12a | vs. | BoGRF12b | 0.0262 | 0.3152 | 0.083122 | Segmental | Purify selection | 10.50667 |

| BoGRF12a | vs. | BoGRF12c | 0.0641 | 0.3298 | 0.19436 | Segmental | Purify selection | 10.99333 |

| BoGRF12b | vs. | BoGRF12c | 0.0457 | 0.3263 | 0.140055 | Segmental | Purify selection | 10.87667 |

| BnAGRF2a | vs. | BnCGRF2b | 0 | 0.0575 | 0 | Segmental | Purify selection | 1.916667 |

| BnAGRF2a | vs. | BnCGRF2c | 0.0241 | 0.3105 | 0.077617 | Segmental | Purify selection | 10.35 |

| BnAGRF2a | vs. | BnCGRF2d | 0.0194 | 0.3585 | 0.054114 | Segmental | Purify selection | 11.95 |

| BnAGRF2a | vs. | BnAGRF2e | 0.0208 | 0.3882 | 0.053581 | Segmental | Purify selection | 12.94 |

| BnCGRF2b | vs. | BnCGRF2c | 0.0241 | 0.3447 | 0.069916 | Segmental | Purify selection | 11.49 |

| BnCGRF2b | vs. | BnCGRF2d | 0.0523 | 0.4536 | 0.1153 | Segmental | Purify selection | 15.12 |

| BnCGRF2b | vs. | BnAGRF2e | 0.0208 | 0.4163 | 0.049964 | Segmental | Purify selection | 13.87667 |

| BnCGRF2c | vs. | BnCGRF2d | 0.0339 | 0.2875 | 0.117913 | Segmental | Purify selection | 9.583333 |

| BnCGRF2c | vs. | BnAGRF2e | 0.0392 | 0.313 | 0.12524 | Segmental | Purify selection | 10.43333 |

| BnCGRF2d | vs. | BnAGRF2e | 0.005 | 0.1125 | 0.044444 | Segmental | Purify selection | 3.75 |

| BnAGRF3b | vs. | BnAGRF3c | 0.021 | 0.4534 | 0.046317 | Segmental | Purify selection | 15.11333 |

| BnAGRF3b | vs. | BnCGRF3d | 0.021 | 0.4095 | 0.051282 | Segmental | Purify selection | 13.65 |

| BnAGRF3c | vs. | BnCGRF3d | 0.0017 | 0.1109 | 0.015329 | Segmental | Purify selection | 3.696667 |

| BnAGRF4b | vs. | BnCGRF4c | 0.0117 | 0.0932 | 0.125536 | Segmental | Purify selection | 3.106667 |

| BnCGRF6a | vs. | BnAGRF6c | 0.0399 | 0.4429 | 0.090088 | Segmental | Purify selection | 14.76333 |

| BnCGRF6a | vs. | BnCGRF6d | 0.0321 | 0.4324 | 0.074237 | Segmental | Purify selection | 14.41333 |

| BnAGRF6c | vs. | BnCGRF6d | 0.0099 | 0.1354 | 0.073117 | Segmental | Purify selection | 4.513333 |

| BnAGRF7a | vs. | BnAGRF7c | 0.0175 | 0.3219 | 0.054365 | Segmental | Purify selection | 10.73 |

| BnAGRF7a | vs. | BnCGRF7d | 0.0175 | 0.3133 | 0.055857 | Segmental | Purify selection | 10.44333 |

| BnAGRF7c | vs. | BnCGRF7d | 0.0083 | 0.102 | 0.081373 | Segmental | Purify selection | 3.4 |

| BnAGRF8a | vs. | BnCGRF8b | 0.0018 | 0.1617 | 0.011132 | Segmental | Purify selection | 5.39 |

| BnAGRF8a | vs. | BnCGRF8d | 0.0186 | 0.4227 | 0.044003 | Segmental | Purify selection | 14.09 |

| BnCGRF8b | vs. | BnCGRF8d | 0.0162 | 0.3483 | 0.046512 | Segmental | Purify selection | 11.61 |

| BnCGRF12a | vs. | BnAGRF12b | 0.0079 | 0.0522 | 0.151341 | Segmental | Purify selection | 1.74 |

| BnCGRF12a | vs. | BnCGRF12c | 0.0276 | 0.3337 | 0.082709 | Segmental | Purify selection | 11.12333 |

| BnCGRF12a | vs. | BnAGRF12d | 0.0244 | 0.3345 | 0.072945 | Segmental | Purify selection | 11.15 |

| BnCGRF12a | vs. | BnAGRF12e | 0.0389 | 0.3673 | 0.105908 | Segmental | Purify selection | 12.24333 |

| BnCGRF12a | vs. | BnCGRF12f | 0.0825 | 0.4056 | 0.203402 | Segmental | Purify selection | 13.52 |

| BnAGRF12b | vs. | BnCGRF12c | 0.0267 | 0.3046 | 0.087656 | Segmental | Purify selection | 10.15333 |

| BnAGRF12b | vs. | BnAGRF12d | 0.0235 | 0.3053 | 0.076973 | Segmental | Purify selection | 10.17667 |

| BnAGRF12b | vs. | BnAGRF12e | 0.0352 | 0.3192 | 0.110276 | Segmental | Purify selection | 10.64 |

| BnAGRF12b | vs. | BnCGRF12f | 0.079 | 0.3765 | 0.209827 | Segmental | Purify selection | 12.55 |

| BnCGRF12c | vs. | BnAGRF12d | 0.0064 | 0.1598 | 0.04005 | Segmental | Purify selection | 5.326667 |

| BnCGRF12c | vs. | BnAGRF12e | 0.0496 | 0.2853 | 0.173852 | Segmental | Purify selection | 9.51 |

| BnCGRF12c | vs. | BnCGRF12f | 0.0629 | 0.3035 | 0.207249 | Segmental | Purify selection | 10.11667 |

| BnAGRF12d | vs. | BnAGRF12e | 0.048 | 0.2504 | 0.191693 | Segmental | Purify selection | 8.346667 |

| BnAGRF12d | vs. | BnCGRF12f | 0.0632 | 0.2956 | 0.213802 | Segmental | Purify selection | 9.853333 |

| BnAGRF12e | vs. | BnCGRF12f | 0.0049 | 0.1385 | 0.035379 | Segmental | Purify selection | 4.616667 |

| BnAGRF13a | vs. | BnCGRF13b | 0.0387 | 0.0713 | 0.542777 | Segmental | Purify selection | 2.376667 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duan, S.; Wang, J. Genome-Wide Analysis Unveils the Evolutionary Impact of Allopolyploidization on the 14-3-3 Gene Family in Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Genes 2025, 16, 1305. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111305

Duan S, Wang J. Genome-Wide Analysis Unveils the Evolutionary Impact of Allopolyploidization on the 14-3-3 Gene Family in Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Genes. 2025; 16(11):1305. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111305

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuan, Shengxing, and Jing Wang. 2025. "Genome-Wide Analysis Unveils the Evolutionary Impact of Allopolyploidization on the 14-3-3 Gene Family in Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.)" Genes 16, no. 11: 1305. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111305

APA StyleDuan, S., & Wang, J. (2025). Genome-Wide Analysis Unveils the Evolutionary Impact of Allopolyploidization on the 14-3-3 Gene Family in Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Genes, 16(11), 1305. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16111305