Genetic Interrelationship Among Newly-Bred Mutant Lines of Wheat Using Diagnostic Simple Sequence Repeat Markers and Phenotypic Traits Under Drought

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Genotyping

Selection of SSR Markers and Genotyping

2.3. PCR Amplification

2.4. Phenotyping Protocols

2.5. Agronomic Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Agronomic Data Analysis

2.6.2. Marker Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Genetic Diversity Using SSR Markers

3.1.1. Genetic Parameters

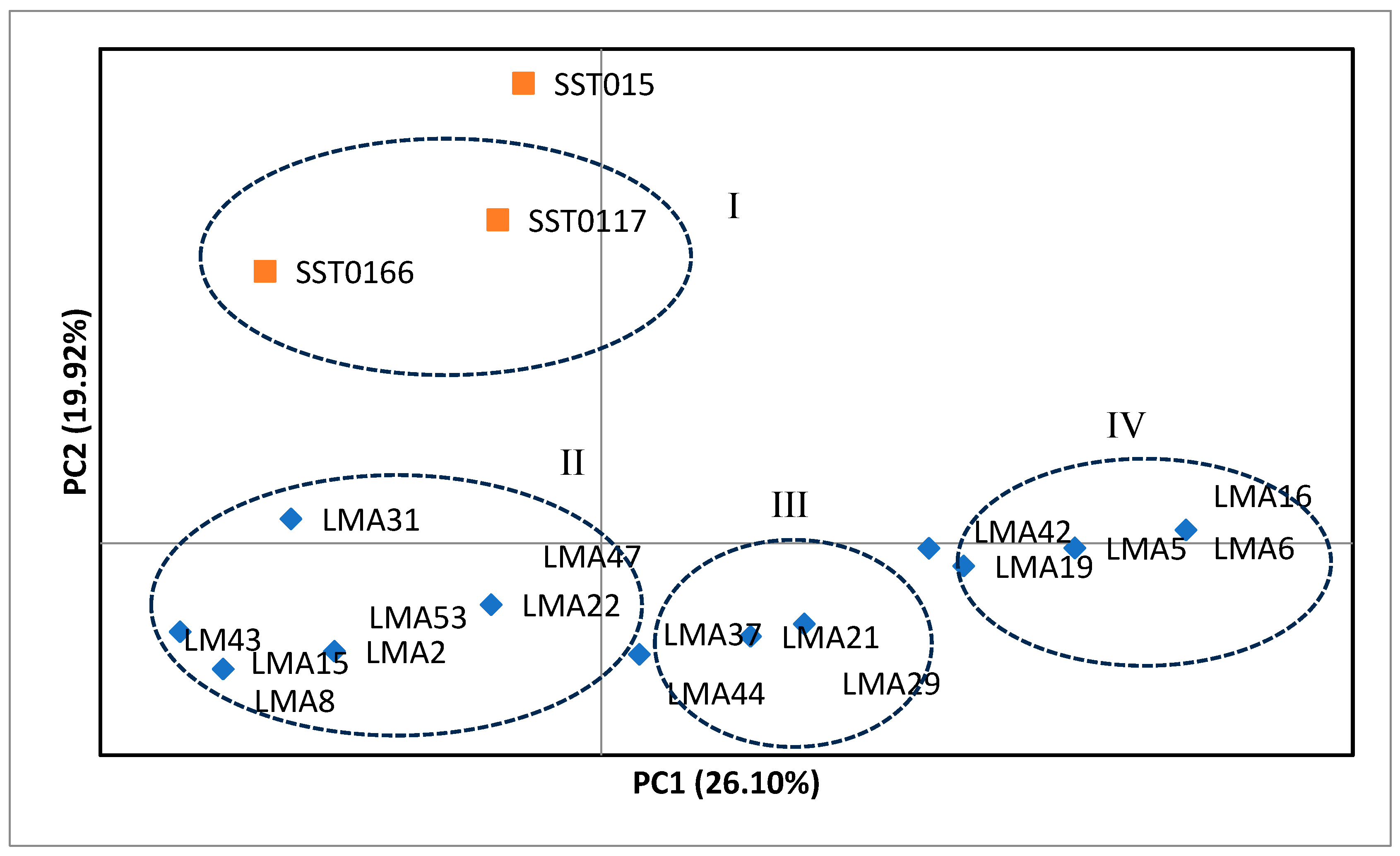

3.1.2. Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA)

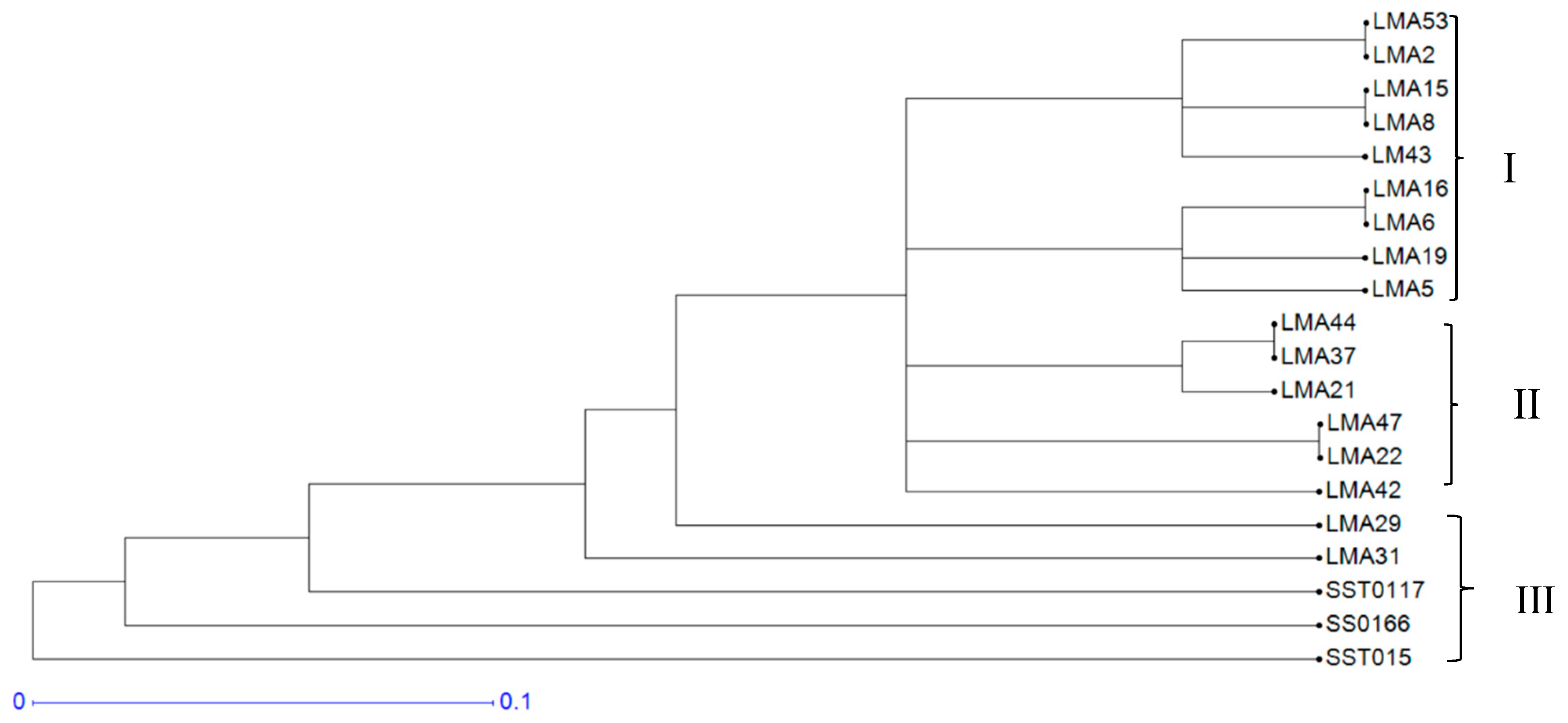

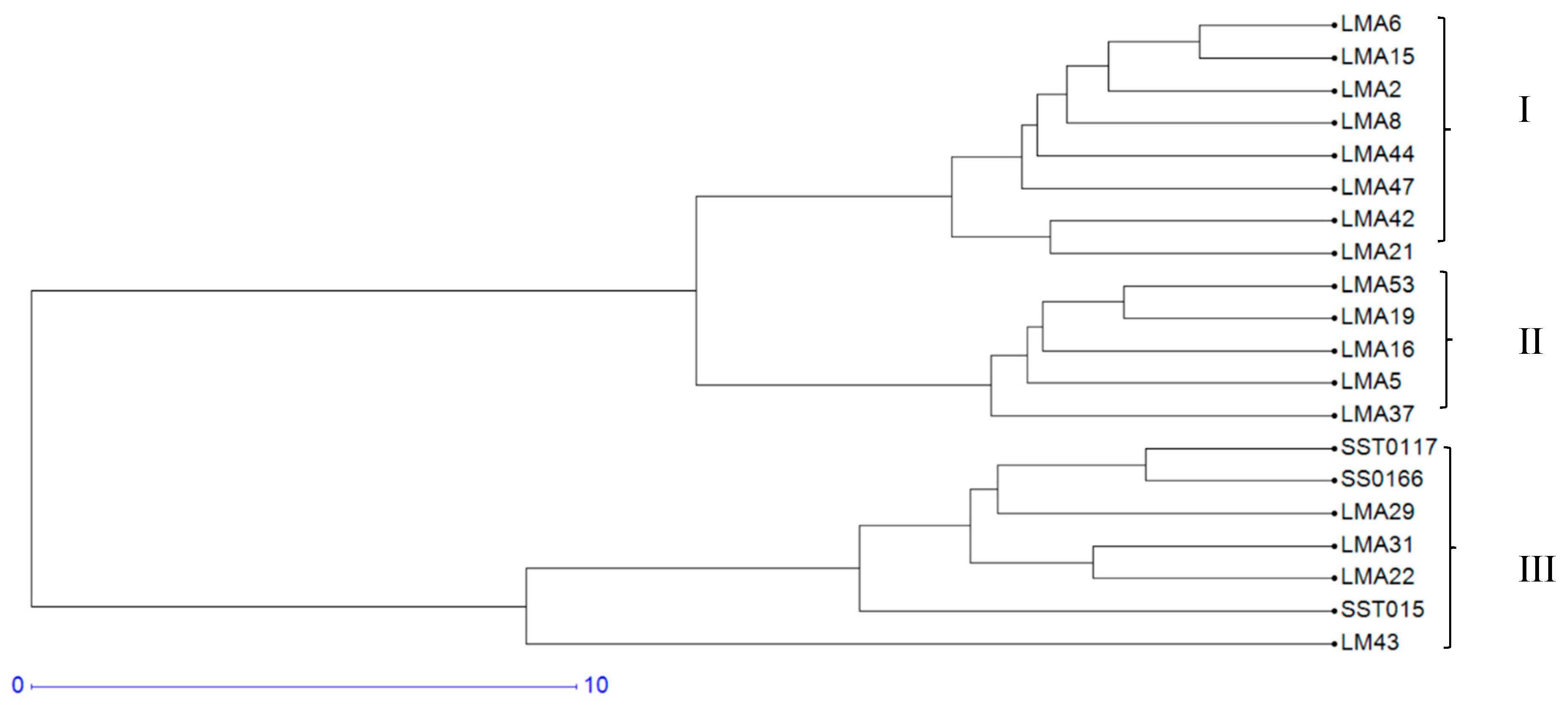

3.1.3. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis

3.2. Phenotyping Based on Agro-Morphological Traits

3.2.1. Genotypic Variation for Agronomic Performance

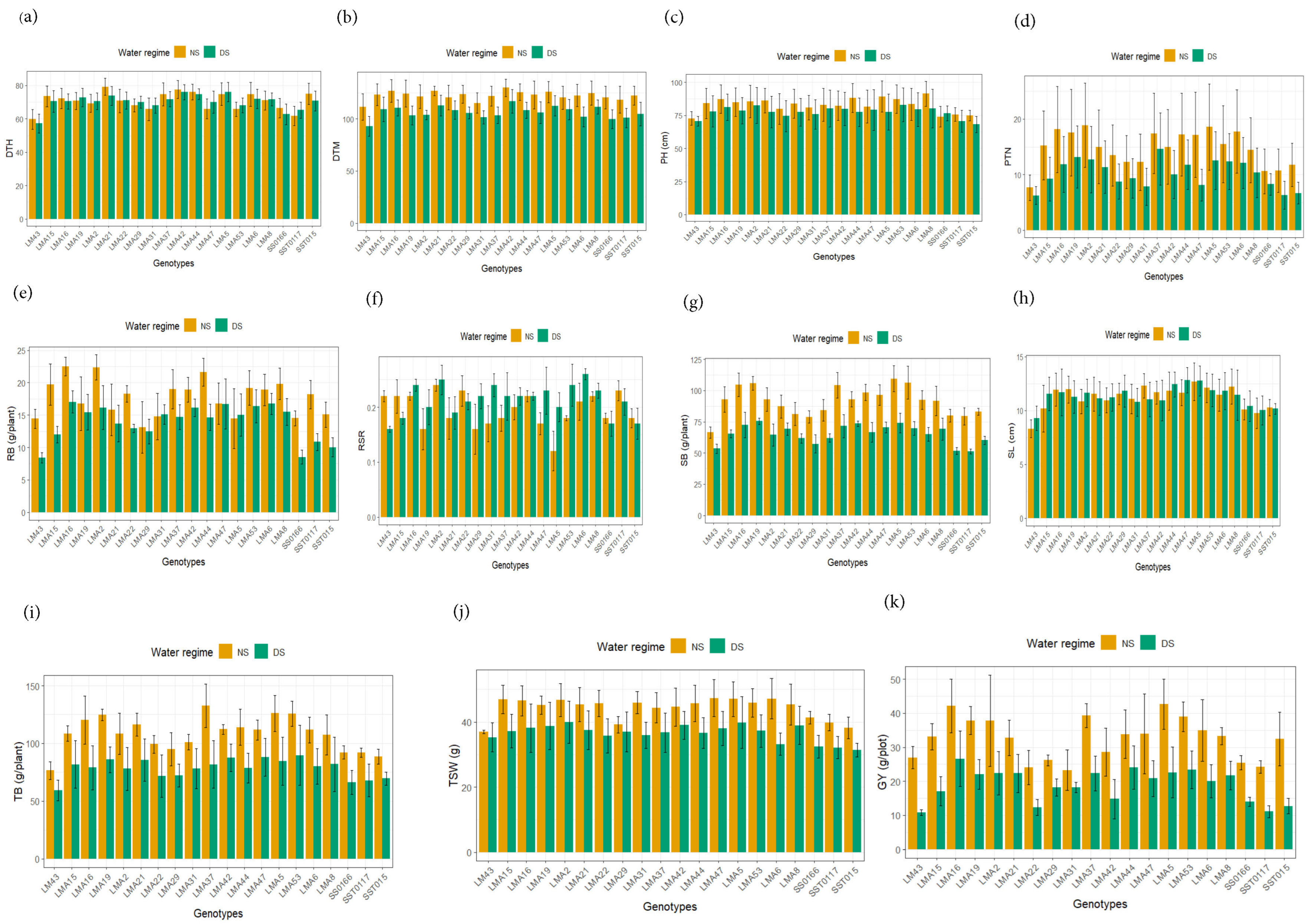

3.2.2. Agronomic Performance Under Non-Stressed and Drought-Stressed Conditions

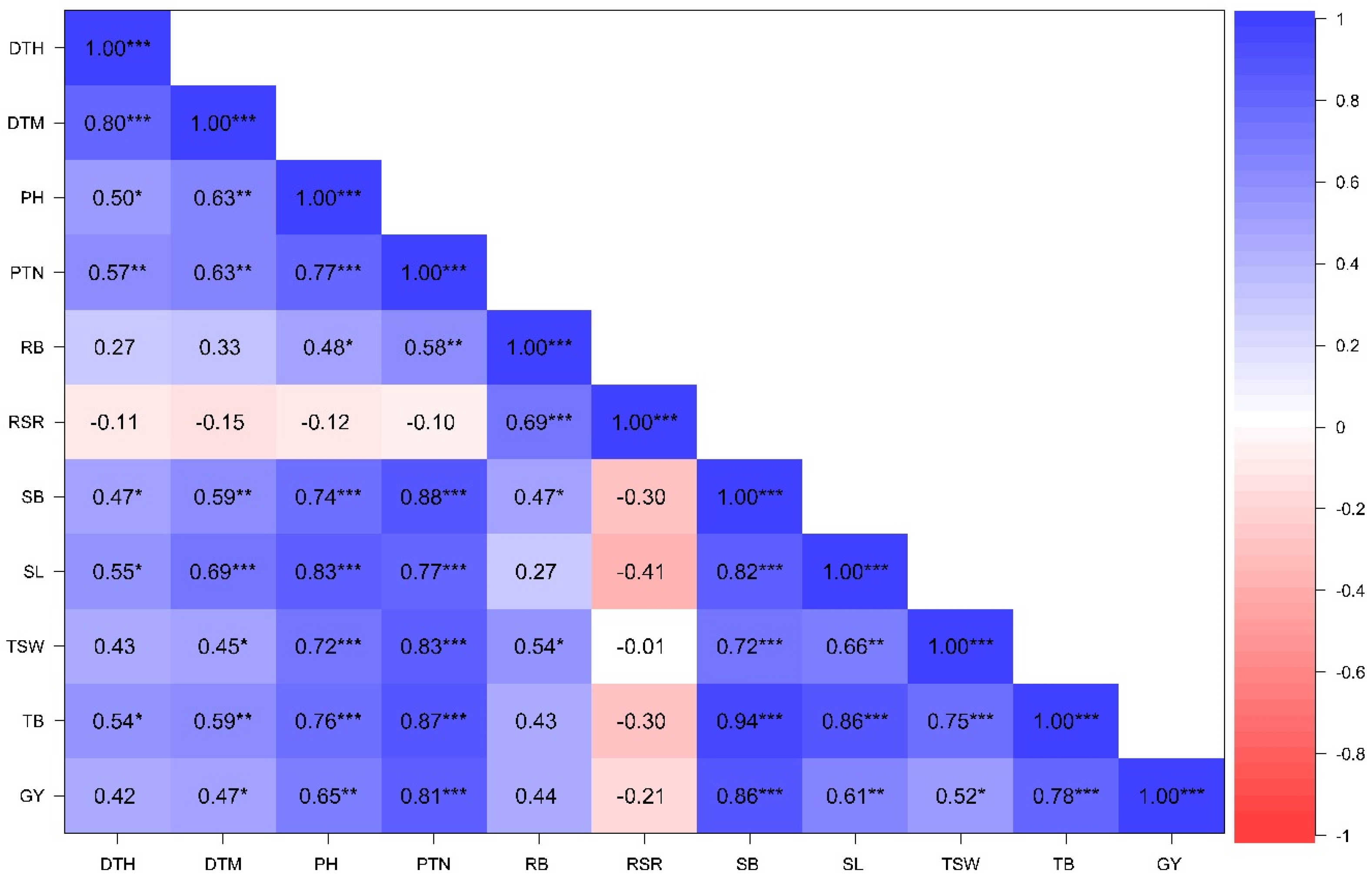

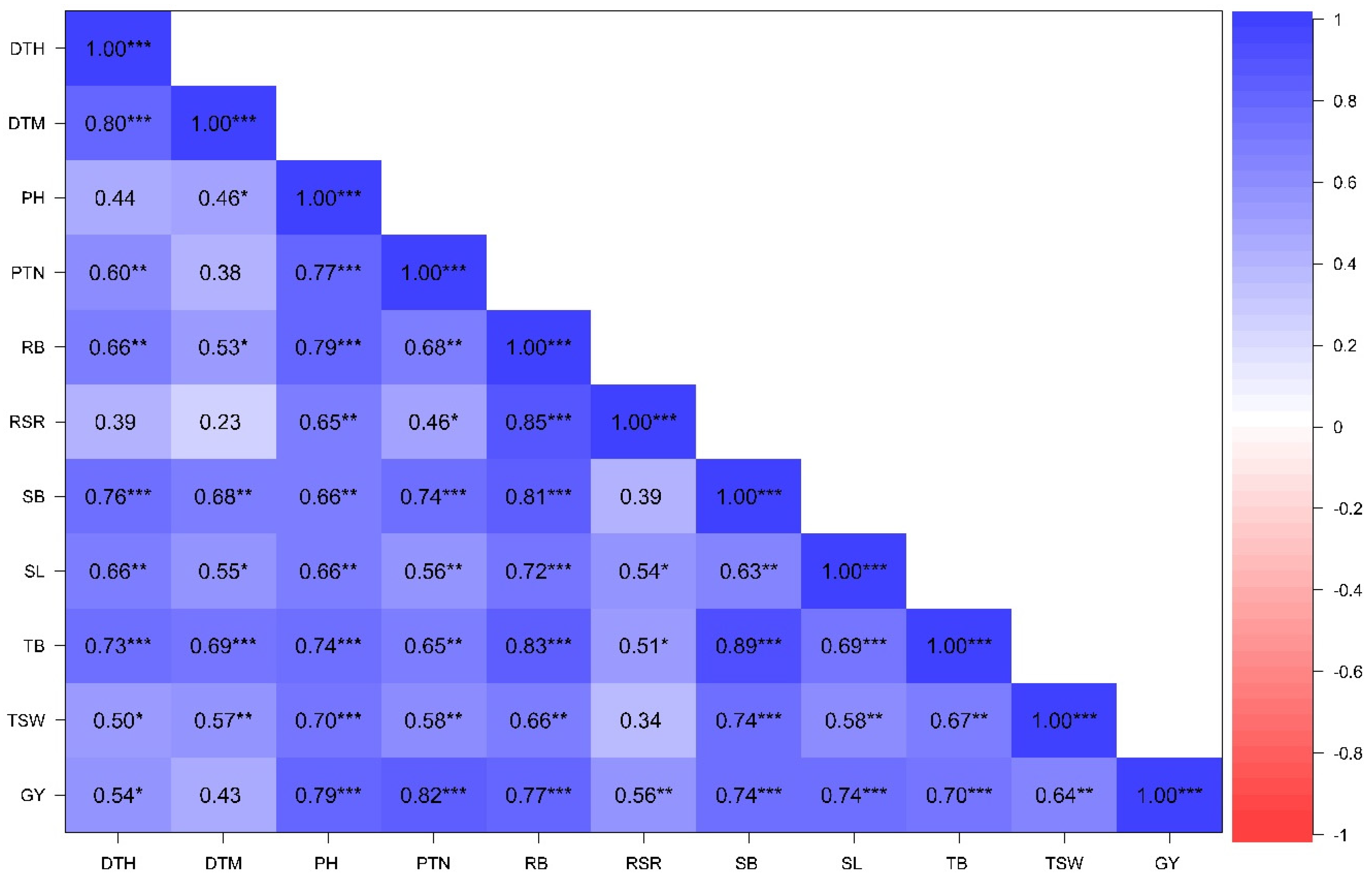

3.2.3. Associations Among Phenotypic Traits Under Contrasting Water Regimes

3.2.4. Multivariate Relationships

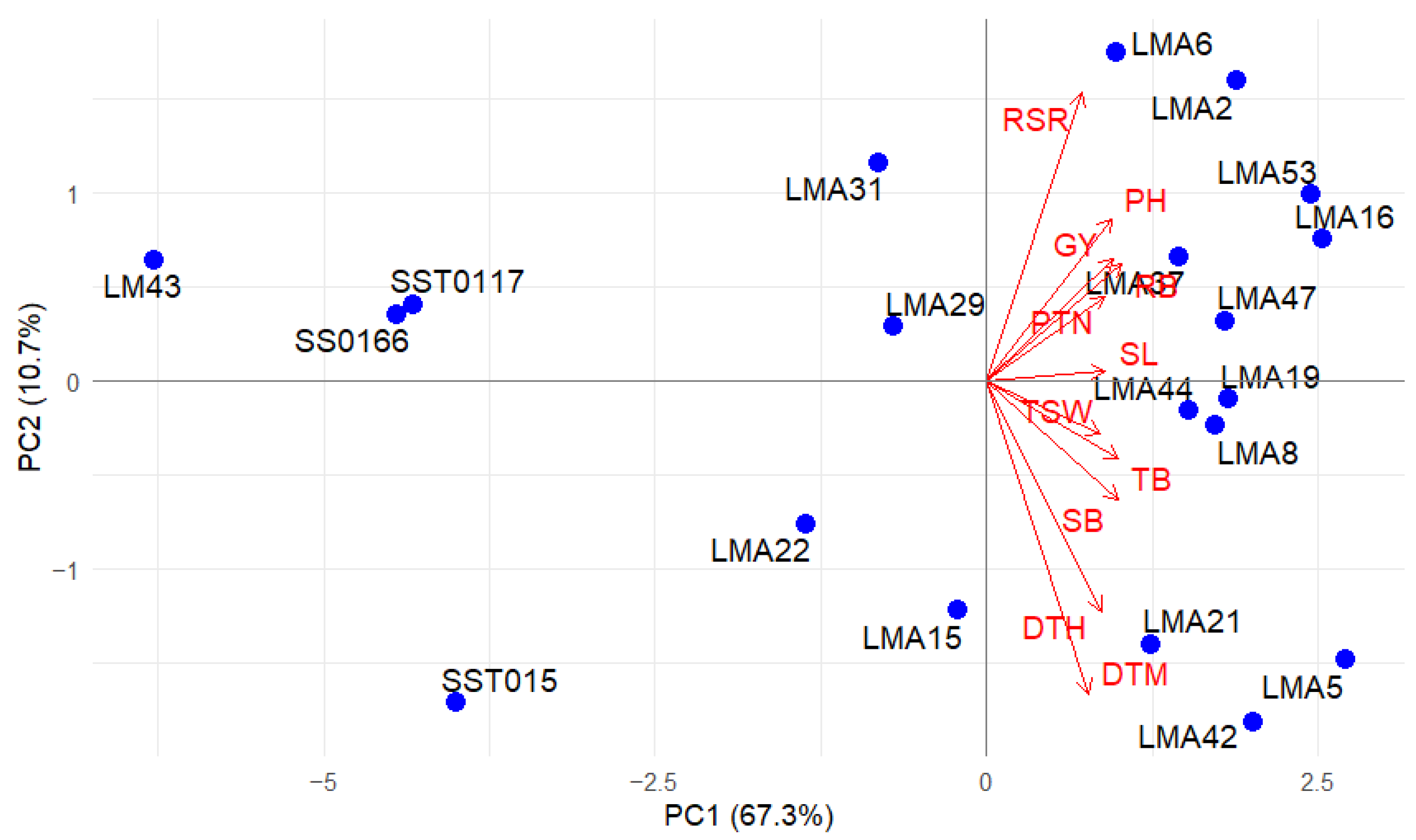

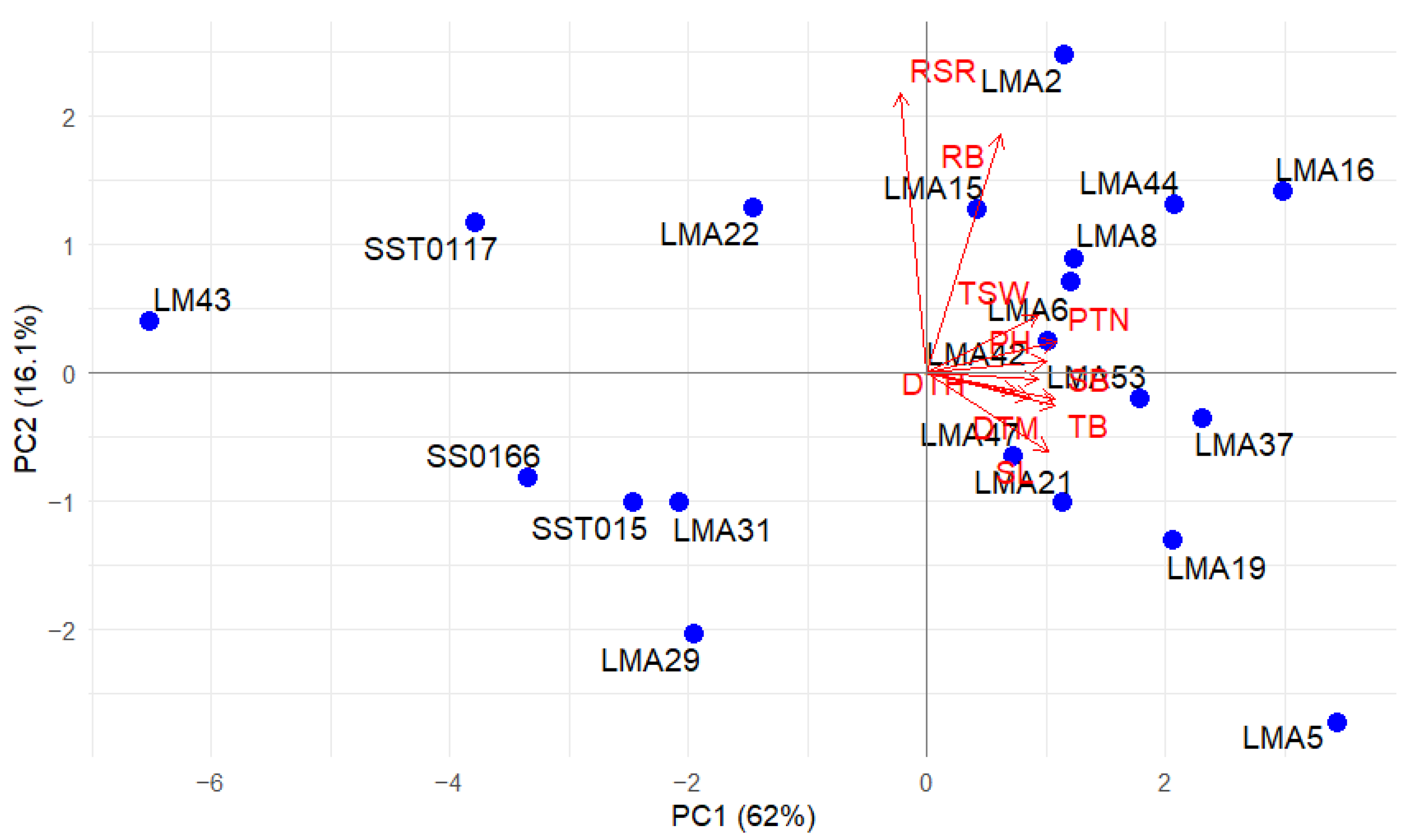

3.2.5. Principal Component Biplots

3.2.6. Cluster Analysis Based on Phenotypic Traits

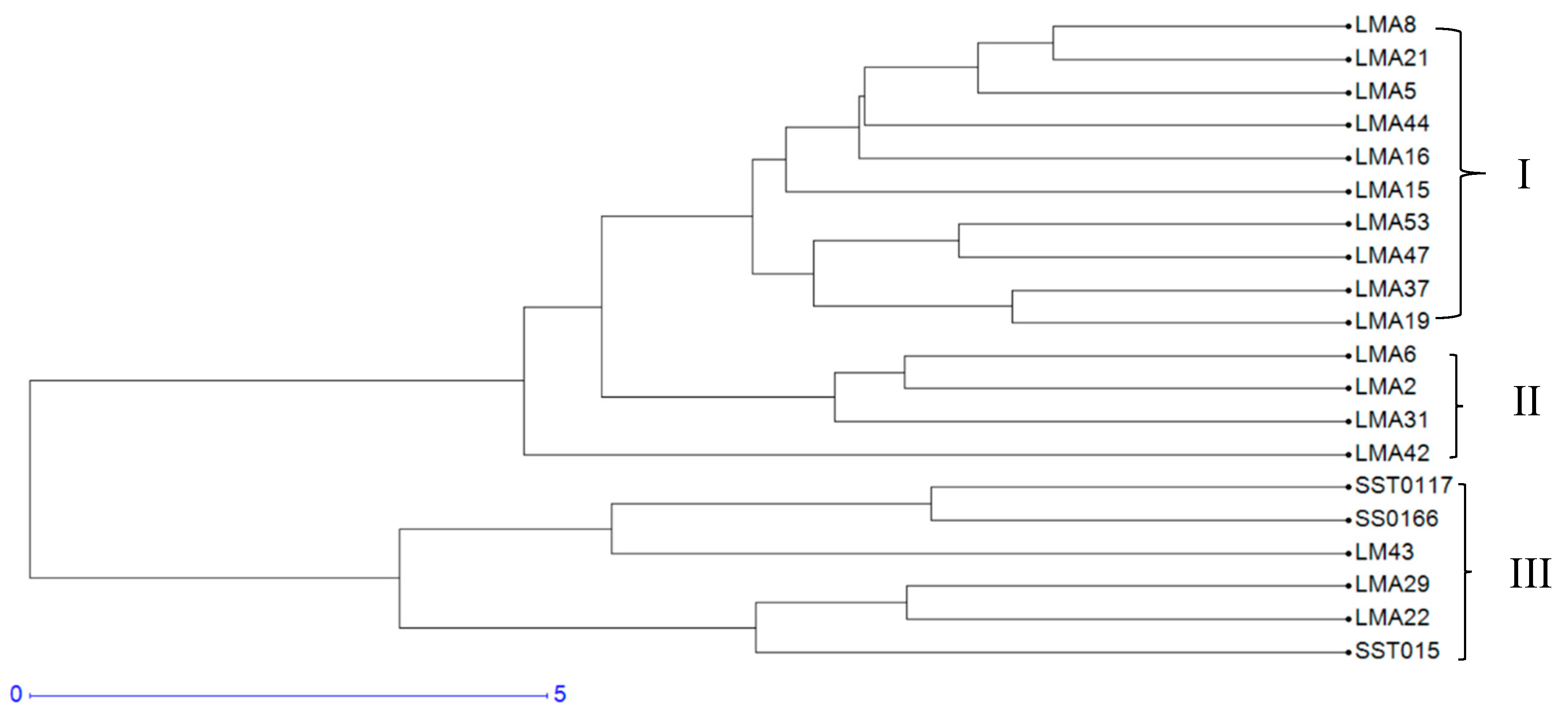

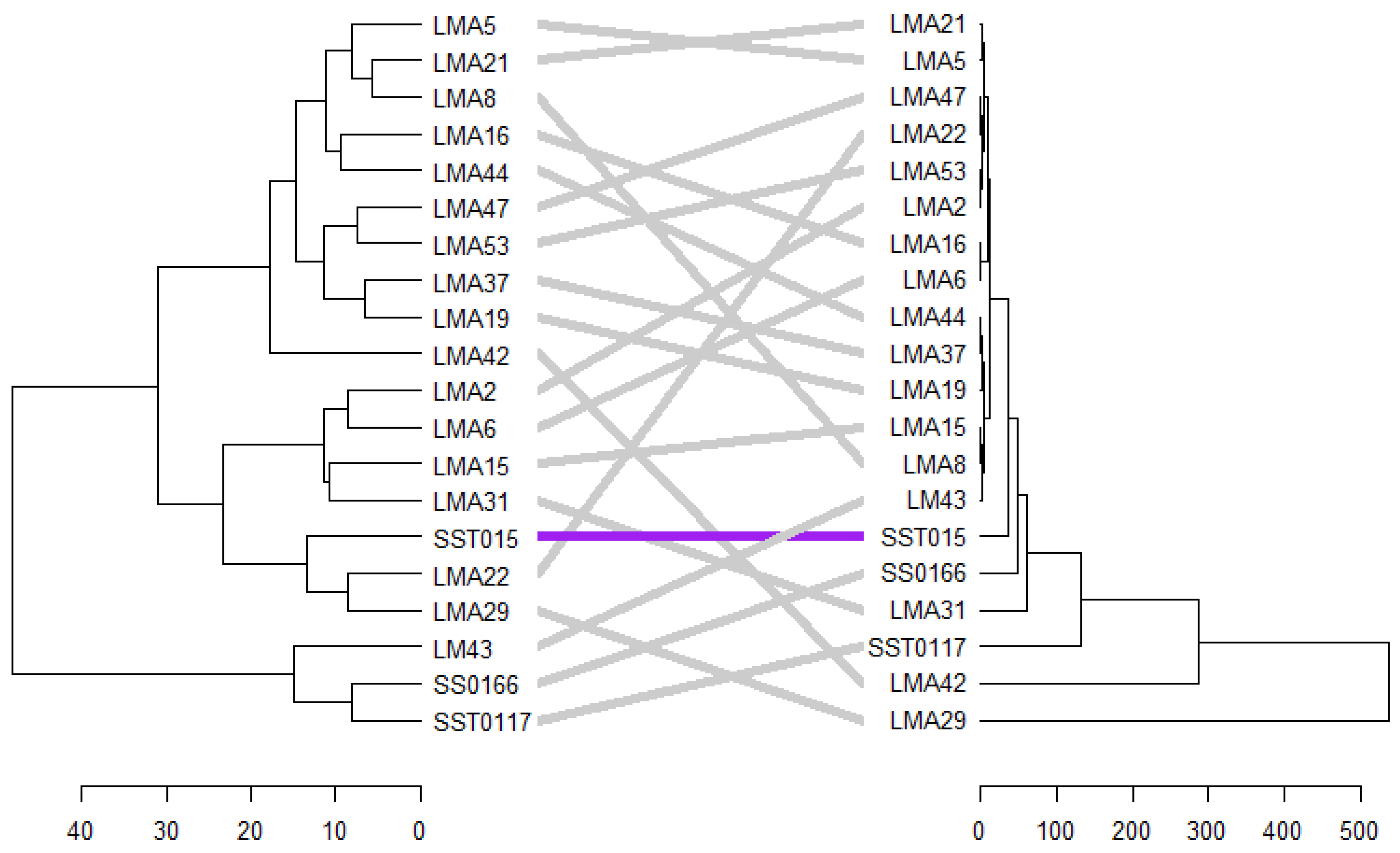

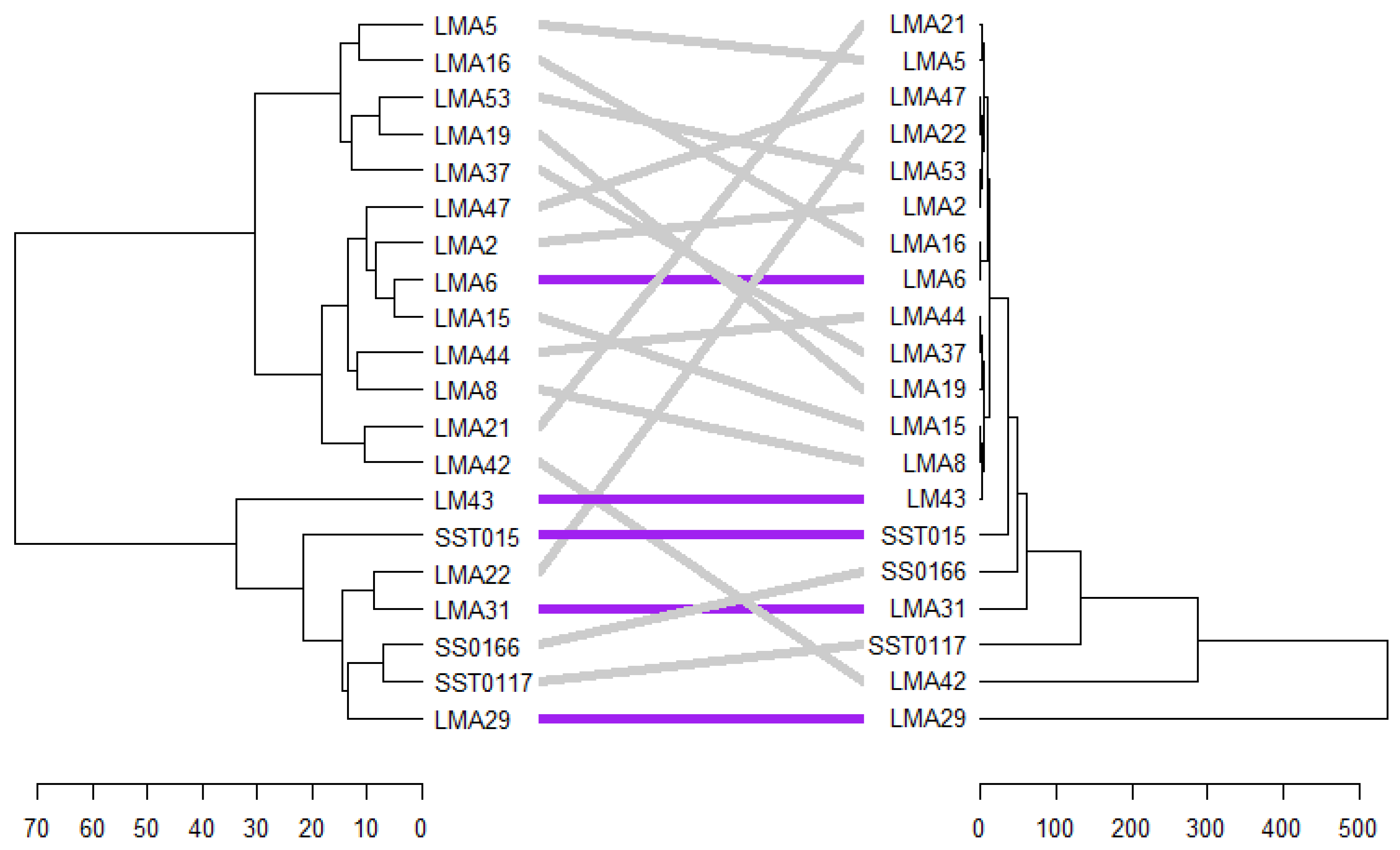

3.2.7. Phenotypic and Genotypic Hierarchical Cluster

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations and Future

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Alotaibi, M.; El-Hendawy, S.; Mohammed, N.; Alsamin, B.; Refay, Y. Appropriate application methods for salicylic acid and plant nutrients combinations to promote morpho-physiological traits, production, and water use efficiency of wheat under normal and deficit irrigation in an arid climate. Plants 2023, 12, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; Singh, M.; Grewal, S.; Razzaq, A.; Wani, S.H. Wheat proteins: A valuable resources to improve nutritional value of bread. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 769681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Hameed, A.; Tahir, M.F. Wheat quality: A review on chemical composition, nutritional attributes, grain anatomy, types, classification, and function of seed storage proteins in bread making quality. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1053196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhua, S.; Kumar, K.; Kumar, Y.; Singh, L.; Sharanagat, V.S. Composition, characteristics and health promising prospects of black wheat: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 112, 780–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, P.; Dewanjee, S. Unrevealing the mechanisms behind the cardioprotective effect of wheat polyphenolics. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 3543–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottaleb, K.A.; Kruseman, G.; Frija, A.; Sonder, K.; Lopez-Ridaura, S. Projecting wheat demand in China and India for 2030 and 2050: Implications for food security. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1077443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Guo, W.; Gou, J.; Hu, Z.; Liu, J.; Ma, J.; Zong, Y.; Xin, M.; Chen, W.; Li, Q. Wheat2035: Integrating pan-omics and advanced biotechnology for future wheat design. Mol. Plant. 2025, 18, 272–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, R.; Wang, H.; Li, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhen, W.; Duan, H.; Yan, G.; Li, Y. Transcriptomics analyses reveal wheat responses to drought stress during reproductive stages under field conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 210582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savadi, S.; Prasad, P.; Kashyap, P.; Bhardwaj, S. Molecular breeding technologies and strategies for rust resistance in wheat (Triticum aestivum) for sustained food security. Plant Pathol. 2018, 67, 771–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparas, M.; Zobel, Z.; Castanho, A.D.; Schwalm, C.R. Increasing risks of crop failure and water scarcity in global breadbaskets by 2030. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 104013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, M.; Nazzaro, C.; Marotta, G.; Caracciolo, F. Land degradation and climate change: Global impact on wheat yields. Land. Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, K.J.; Zörb, C.; Geilfus, C.M. Drought and crop yield. Plant Biol. 2021, 23, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Herrera, L.; Crossa, J.; Huerta-Espino, J.; Vargas, M.; Mondal, S.; Velu, G.; Payne, T.; Braun, H.; Singh, R. Genetic gains for grain yield in CIMMYT’s semi-arid wheat yield trials grown in suboptimal environments. Crop Sci. 2018, 58, 1890–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerard, G.S.; Crespo-Herrera, L.A.; Crossa, J.; Mondal, S.; Velu, G.; Juliana, P.; Huerta-Espino, J.; Vargas, M.; Rhandawa, M.S.; Bhavani, S. Grain yield genetic gains and changes in physiological related traits for CIMMYT’s High Rainfall Wheat Screening Nursery tested across international environments. Field Crops Res. 2020, 249, 107742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joudi, M.; Ahmadi, A.; Mohammadi, V.; Abbasi, A.; Mohammadi, H. Genetic changes in agronomic and phenologic traits of Iranian wheat cultivars grown in different environmental conditions. Euphytica 2014, 196, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, M.R.; Ghimire, S.; Pandey, M.P.; Dhakal, K.H.; Thapa, D.B.; Poudel, H.K. Evaluation of wheat genotypes under irrigated heat stress drought conditions. J. Biol. Today’s World 2020, 9, 212. [Google Scholar]

- Dadrasi, A.; Chaichi, M.; Nehbandani, A.; Soltani, E.; Nemati, A.; Salmani, F.; Heydari, M.; Yousefi, A.R. Global insight into understanding wheat yield and production through Agro-Ecological Zoning. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Nayak, J.K.; Pal, N.; Tyagi, S.; Yadav, R.R.; Joshi, P.; Malik, R.; Dhaka, N.S.; Singh, V.K.; Kumar, S. Development and characterization of an EMS-mutagenized population of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) for agronomic trait variation and increased micronutrients content. Cereal Res. Commun. 2024, 53, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Guan, X.; Gan, Y.; Liu, G.; Zou, C.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Hao, Q.; Ni, F. Creating large EMSpopulations for functional genomics breeding in wheat. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komura, S.; Yoshida, K.; Jinno, H.; Oono, Y.; Handa, H.; Takumi, S.; Kobayashi, F. Identification of the causal mutation in early heading mutant of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) using MutMap approach. Mol. Breed. 2024, 44, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zheng, S.; Tian, S.; Si, Y.; Ma, S.; Ling, H.-Q.; Niu, J. Natural variant of Rht27, a dwarfing gene, enhances yield potential in wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawcha, K.T.; Ndolo, D.; Yang, W.; Babalola, O.O. Development of EMS Mutagenized Wheat Mutant Lines Resistant to Fusarium Crown Rot and Fusarium Head Blight. Plant Breed. 2024, 12, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OlaOlorun, B.M.; Shimelis, H.; Laing, M.; Mathew, I. Development of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) populations for drought tolerance and improved biomass allocation through Ethyl Methanesulphonate mutagenesis. Front. Agron. 2021, 3, 655820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharib, M.; Qabil, N.; Salem, A.; Ali, M.; Awaad, H.; Mansour, E. Characterization of wheat landraces and commercial cultivars based on morpho-phenological and agronomic traits. Cereal Res. Commun. 2021, 49, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanic, V.; Lalic, Z.; Berakovic, I.; Jukic, G.; Varnica, I. Morphological characterization of 1322 winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) varieties from EU referent collection. Agriculture 2024, 14, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohi-Ud-Din, M.; Hossain, M.A.; Rohman, M.M.; Uddin, M.N.; Haque, M.S.; Dessoky, E.S.; Alqurashi, M.; Aloufi, S. Assessment of genetic diversity of bread wheat genotypes for drought tolerance using canopy reflectance-based phenotyping and SSR marker-based genotyping. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Al-Ashkar, I.; Al-Doss, A.; Al-Gaadi, K.A.; Zeyada, A.M.; Ghazy, A. Assessing Heat Stress Tolerance of Wheat Genotypes through Integrated Molecular and Physio-Biochemical Analyses. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavandpouri, F.; Farshadfar, E.; Cheghamirza, K.; Farshadfar, M.; Bihamta, M.R.; Mahdavi, A.M.; Jelodar, N. Identification of molecular markers associated with genomic regions controlling agronomic traits in bread wheat genotypes under different moisture conditions. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 43, 631–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Ahmad, M.; Shani, M.Y.; Khan, M.K.R.; Rahimi, M.; Tan, D.K. Identifying the physiological traits associated with DNA marker using genome wide association in wheat under heat stress. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, S.; Döring, T.F.; Jones, H.E.; Snape, J.; Wingen, L.U.; Wolfe, M.S.; Leverington-Waite, M.; Griffiths, S. Natural selection towards wild-type in composite cross populations of winter wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shew, A.; Tack, J.; Nalley, L.; Chaminuka, P. Yield reduction under climate warming varies among wheat cultivars in South Africa. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, M.; Abiodun, B.J. Projected changes in drought characteristics over the Western Cape, South Africa. Meteorol. Appl. 2020, 27, e1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theron, S.; Archer, E.; Midgley, S.; Walker, S. Agricultural perspectives on the 2015–2018 Western Cape drought, South Africa: Characteristics and spatial variability in the core wheat growing regions. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 304, 108405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajilogba, C.F.; Walker, S. Modeling climate change impact on dryland wheat production for increased crop yield in the Free State, South Africa, using GCM projections and the DSSAT model. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1067008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nxumalo, G.; Bashir, B.; Alsafadi, K.; Bachir, H.; Harsányi, E.; Arshad, S.; Mohammed, S. Meteorological drought variability and its impact on wheat yields across South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaolorun, B.M.; Shimelis, H.A.; Hussein, A.; Mathew, I.; Laing, M.D. Optimising the dosage of ethyl methanesulphonate mutagenesis in selected wheat genotypes. S. Afr. J. Plant Soil 2019, 36, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makebe, A.; Shimelis, H.; Mashilo, J. Selection of M5 mutant lines of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) for agronomic traits and biomass allocation under drought stress and non-stressed conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1314014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodig, D.; Zoric, M.; Kobiljski, B.; Savic, J.; Kandic, V.; Quarrie, S.; Barnes, J. Genetic and association mapping study of wheat agronomic traits under contrasting water regimes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 6167–6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş-Sönmezoğlu, Ö.; Çevik, E.; Terzi-Aksoy, B. Assessment of some bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes for drought tolerance using SSR and ISSR markers. Biotech. Stud. 2022, 31, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunilkumar, V.; Krishna, H.; Devate, N.B.; Manjunath, K.K.; Chauhan, D.; Singh, S.; Sinha, N.; Singh, J.B.; TL, P.; Pal, D. Marker-assisted selection for transfer of QTLs to a promising line for drought tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1147200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DAFF: Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Wheat Production Guideline; DAFF: Pretoria, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, T.; Simko, V.; Levy, M.; Xie, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zemla, J. Package “corrplot”: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix. Statistician 2017, 56, e24. [Google Scholar]

- Team RC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. Factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses. 2020, pp. 1–84. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=factoextra (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P.E. GenAlex 6.5: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population software for teaching and research—An update. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2537–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, S.; Poczai, P.; Cernák, I.; Gorji, A.M.; Hegedűs, G.; Taller, J. PICcalc: An online program to calculate polymorphic information content for molecular genetic studies. Biochem. Genet. 2012, 50, 670–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrier, X.; Jacquemoud-Collet, J. DARwin Software: Dissimilarity Analysis and Representation for Windows. 2006. Available online: http://darwinciradfr/darwin (accessed on 1 March 2013).

- Galili, T. Dendextend: An R package for visualizing, adjusting and comparing trees of hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3718–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Chaudhary, H.K.; Singh, K.; Kumar, N.; Dhillon, K.S.; Sharma, M.; Sood, V. Genetic diversity dissection and population structure analysis for augmentation of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) germplasm using morpho-molecular markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2024, 71, 4093–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, V.K.; Sharma, R.; Chand, S.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, N.; Jain, N.; Singh, A. Elucidating molecular diversity in spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L. em. Thell.) under terminal heat stress environment using morpho-physiological traits and SSR markers. Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2022, 82, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M.A.; Al-falahi, A.; Hamedullah, M.S.; Al-Hattab, Z.N. Molecular evaluation of salt tolerance induced by sodium azide in immature embryos of two wheat cultivars. J. Biotechnol. Res. Ctr. 2019, 13, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, A.; Sarsu, F. Genetic diversity in sodium azide induced wheat mutants studied by SSR markers. Trak. Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 2018, 19, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangian-Kashani, S.; Azadi, A.; Khaghani, S.; Changizi, M.; Gomarian, M. Association analysis and evaluation of genetic diversity in wheat genotypes using SSR markers. Biol. Futura. 2021, 72, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Ahmed, J.U.; Hasan, M.; Mohi-Ud-Din, M. Assessment of genetic variation among wheat genotypes for drought tolerance utilizing microsatellite markers and morpho-physiological characteristics. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhabela, S.S.; Shimelis, H.; Mashilo, J. Genetic differentiation of selected drought and heat tolerant wheat genotypes using simple sequence repeat markers and agronomic traits. S. Afr. J. Plant Soil 2020, 37, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, O.; Bangash, S.A.K.; Ibrahim, M.; Shahab, S.; Khattak, S.H.; Ud Din, I.; Khan, M.N.; Hafeez, A.; Wahab, S.; Ali, B. Evaluation of agronomic performance and genetic diversity analysis using simple sequence repeats markers in selected wheat lines. Sustainability 2022, 15, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, S.; Demirel, F. Molecular identification and population structure of emmer and einkorn wheat lines with different ploidy levels using SSR markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2024, 71, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquijo-Zamora, L.; Pereira-Lorenzo, S.; Romero-Rodríguez, Á.; Lombardero-Fernández, M.; Ramos-Cabrer, A.M.; Fernández-Otero, C.I. Genetic diversity of local wheat (triticum aestivum L.) and traceability in the production of galician bread (protected geographical indication) by microsatellites. Agriculture 2024, 15, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnaw, T.; Mulugeta, B.; Haileselassie, T.; Geleta, M.; Ortiz, R.; Tesfaye, K. Genetic diversity of durum wheat (Triticum turgidum L. ssp. Durum, desf) germplasm as revealed by morphological and SSR markers. Genes 2023, 14, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tian, G.; Zhao, Y.; Li, C.; Cao, Q.; Han, R.; Shi, Z.; He, M. Plant height and its relationship with yield in wheat under different irrigation regime. Irrig. Sci. 2020, 38, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.-G.; Zhang, X.-B.; Quan, M.; Li, F.-J.; Tao, R.-R.; Min, Z.; Li, C.-Y.; Zhu, X.-K.; Guo, W.-S.; Ding, J.-F. Tiller fertility is critical for improving grain yield, photosynthesis, and nitrogen efficiency in wheat. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 2054–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, Z.; Iqbal, R.; Jabbar, A.; Zahra, N.; Saleem, B.; Kiran, A.; Maqbool, S.; Rasheed, A.; Naeem, M.K.; Khan, M.R. Genetic signature controlling root system architecture in diverse spring wheat germplasm. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.P. Root phenotypes for improved nutrient capture: An underexploited opportunity for global agriculture. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Berni, J.A.; Deery, D.M.; Rozas-Larraondo, P.; Condon, A.G.; Rebetzke, G.J.; James, R.A.; Bovill, W.D.; Furbank, R.T.; Sirault, X.R. High throughput determination of plant height, ground cover, and above-ground biomass in wheat with LiDAR. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Yousaf, M.W.; Ahmed, H.G.M.-D.; Fatima, N.; Alam, B. Assessing genetic diversity for some Pakistani bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes under drought stress based on yield traits. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2024, 71, 3563–3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandeep, N.; Kumar, B.; Chavan, A.L. Microsatellite Marker–Driven Genetic Diversity and Breeding Potential Assessment in Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench): A Multi-parent Approach. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 24, 1496–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entry No. | Genotype | Pedigree | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LMA2 | Mutant | ACCI |

| 2 | LMA5 | Mutant | ACCI |

| 3 | LMA6 | Mutant | ACCI |

| 4 | LMA8 | Mutant | ACCI |

| 5 | LMA15 | Mutant | ACCI |

| 6 | LMA16 | Mutant | ACCI |

| 7 | LMA19 | Mutant | ACCI |

| 8 | LMA21 | Mutant | ACCI |

| 9 | LMA22 | Mutant | ACCI |

| 10 | LMA29 | Mutant | ACCI |

| 11 | LMA31 | Mutant | ACCI |

| 12 | LMA37 | Mutant | ACCI |

| 13 | LMA42 | Mutant | ACCI |

| 14 | LM43 | ROLF07*2/6/PVN//CAR422/ANA/5/ BOW/CROW//BUC/PVN/3/YR/4/TRAP#1 | CIMMYT |

| 15 | LMA44 | Mutant | ACCI |

| 16 | LMA47 | Mutant | ACCI |

| 17 | LMA53 | Mutant | ACCI |

| 18 | SS0166 | PBR | Sensako |

| 19 | SST0117 | PBR | Sensako |

| 20 | SST015 | PBR | Sensako |

| Marker Name | Chromosome Location | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Xgwm132 | 6A | F: ACCAAATCGAAACACATCAGG R: CATATCAAGGTCTCCTTCCCC |

| Xgmw484 | 2D | F: ACATCGCTCTTCACAAACCC R: AGTTCCGGTCATGGCTAGG |

| XWMC596 | 7A | F: TCAGCAACAAACATGCTCGG R: CCCGTGTAGGCGGTAGCCTCTT |

| Wmc179 | 6A | F: CATGGTGGCCATGAGTGGAGGT R: CATGATCTTGCGTGTGCGTAGG |

| GWM337 | 1D | F: CCTCTTCCTCCCTCATTAGC R: TGCTAACTGGCCTTTGCC |

| Wms169 | 6A | F: ACCACTGCAGAGAACACATACG R: GTGCTCTGCTCTAAGTGTGGG |

| Wms30 | 2D | F: ATCTTAGCATAGAAGGGAGTGGG R: TTCTGCACCCTGGGTGAT |

| Wmc177 | 2A | F: AGGGCTCTCTTTAATTCTTGCT R: GGTCTATCGTAATCCACCTGTA |

| Wmc532 | 2B | F: GATACATCAAGATCGTGCCAAA R: GGGAGAAATCATTAACGAAGGG |

| Wmc78 | 3B | F: AGTAAATCCTCCCTTCGGCTTC R: AGCTTCTTTGCTAGTCCGTTGC |

| Markers | Product Size (bp) | Na | Ne | I | Ho | He | F | PIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WMS30 | 217–244 | 2.00 | 1.93 | 0.67 | 0.89 | 0.48 | −0.83 | 0.49 |

| Xgwm132 | 97–244 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.69 | 1.00 | 0.50 | −1.00 | 0.50 |

| Xgwm484 | 170–192 | 3.00 | 2.17 | 0.71 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.31 | 0.68 |

| XWMC596 | 159–175 | 3.00 | 2.31 | 0.76 | 0.11 | 0.43 | 0.77 | 0.83 |

| WMS169 | 143–157 | 2.00 | 1.79 | 0.61 | 0.76 | 0.43 | −0.69 | 0.43 |

| WMC179 | 216–376 | 3.00 | 2.53 | 0.90 | 0.98 | 0.57 | −0.76 | 0.77 |

| GWM337 | 189–204 | 1.00 | 1.27 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 1.00 | 0.28 |

| WMC532 | 178–197 | 2.00 | 1.67 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 1.00 | 0.50 |

| WMC78 | 266 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| WMC177 | 200–209 | 2.00 | 1.56 | 0.43 | 0.16 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.61 |

| Mean | - | 2.10 | 1.82 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.51 |

| SE | - | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.09 |

| Change | d.f. | DTH | DTM | PH | PTN | RB | RSR | SB | SL | TB | TSW | GY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rep | 1 | 41.00 * | 302.50 * | 0 ns | 3.86 ns | 0.97 ns | 0.00 ns | 442.29 * | 0.00 ns | 845.3 * | 18.97 | 5.67 ns |

| Genotype (G) | 19 | 173.50 ** | 171.80 ** | 146.83 ** | 57.77 ** | 46.96 ** | 0.00 * | 665.76 ** | 6.75 ** | 960.89 ** | 54.19 ** | 213.76 ** |

| Water regime (W) | 1 | 9.51 ns | 10,530.02 ** | 1163.61 ** | 868.81 | 574.77 ** | 0.01 * | 27,490.10 ** | 0.28 ns | 35,594.95 ** | 2381.70 ** | 7523.40 ** |

| Environment (E) | 1 | 13,634.56 ** | 41,473.60 ** | 50,673.62 ** | 12,147.32 ** | 1493.82 ** | 0.04 ** | 13,381.70 ** | 846.98 ** | 14,525.25 ** | 9905.34 ** | 7789.16 ** |

| G × W | 19 | 15.41 * | 17.64 ns | 23.36 ns | 5.93 ns | 14.10 ns | 0.00 ns | 77.31 ns | 0.97 ns | 145.04 ns | 14.27 * | 27.70 ns |

| G × E | 19 | 15.68 * | 44.11 ns | 180.60 ** | 48.97 ** | 22.92 * | 0.00 ns | 149.51 * | 2.43 * | 240.85 ** | 35.83 ** | 222.45 ** |

| W × E | 1 | 71.5 *6 | 416.03 ** | 108.28 * | 537.14 ** | 36.08 ns | 0.00 ns | 1440.00 ** | 1.85 ns | 2822.40 ** | 130.52 ** | 29.63 ns |

| G × W × E | 19 | 6.39 ns | 52.67 * | 17.99 ns | 4.816 | 5.85 ns | 0.00 ns | 77.72 ns | 1.25 ns | 151.47 * | 21.60 * | 65.32 * |

| Residual | 79 | 7.715 | 29.21 | 22.05 | 3.542 | 11.75 | 0 | 75.6 | 1.061 | 86.48 | 8.282 | 29.99 |

| Drought Stressed | Non-Stressed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traits | PC1 | PC2 | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 |

| DTH | 0.29 | −0.41 | 0.25 | 0.05 | −0.67 |

| DTM | 0.26 | −0.55 | 0.29 | 0.06 | −0.58 |

| GY | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.02 | 0.27 |

| PH | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.33 | −0.03 | 0.02 |

| PTN | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.36 | −0.08 | 0.10 |

| RB | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.21 | −0.62 | 0.04 |

| RSR | 0.24 | 0.51 | −0.07 | −0.73 | −0.13 |

| SB | 0.33 | −0.21 | 0.36 | 0.07 | 0.24 |

| SL | 0.30 | 0.02 | 0.34 | 0.20 | −0.02 |

| TB | 0.33 | −0.14 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.17 |

| TSW | 0.29 | −0.09 | 0.31 | −0.15 | 0.16 |

| Eigenvalue | 7.41 | 1.18 | 6.82 | 1.77 | 1.00 |

| Proportion of total variance (%) | 67.35 | 10.68 | 61.97 | 16.11 | 9.06 |

| Cumulative variance (%) | 67.35 | 78.03 | 61.97 | 78.08 | 87.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makebe, A.; Shimelis, H.; Mashilo, J. Genetic Interrelationship Among Newly-Bred Mutant Lines of Wheat Using Diagnostic Simple Sequence Repeat Markers and Phenotypic Traits Under Drought. Genes 2025, 16, 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101210

Makebe A, Shimelis H, Mashilo J. Genetic Interrelationship Among Newly-Bred Mutant Lines of Wheat Using Diagnostic Simple Sequence Repeat Markers and Phenotypic Traits Under Drought. Genes. 2025; 16(10):1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101210

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakebe, Athenkosi, Hussein Shimelis, and Jacob Mashilo. 2025. "Genetic Interrelationship Among Newly-Bred Mutant Lines of Wheat Using Diagnostic Simple Sequence Repeat Markers and Phenotypic Traits Under Drought" Genes 16, no. 10: 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101210

APA StyleMakebe, A., Shimelis, H., & Mashilo, J. (2025). Genetic Interrelationship Among Newly-Bred Mutant Lines of Wheat Using Diagnostic Simple Sequence Repeat Markers and Phenotypic Traits Under Drought. Genes, 16(10), 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101210