Significant Association Between Abundance of Gut Microbiota and Plasma Levels of microRNAs in Individuals with Metabolic Syndrome and Their Potential as Biomarkers for Metabolic Syndrome: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Collection of Fecal and Plasma Samples from Study Participants

2.3. Bacterial DNA Extraction, 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation, and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

2.4. 16s rRNA Amplicon Sequence Analysis

2.5. Classification of Amplicon Sequences According to Taxonomy

2.6. RNA Extraction from Blood Sample and Quantification of Plasma miRs by RT-qPCR

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of Participants with MetS and Controls

3.2. Comparison of GM Composition Between MetS and Control Groups at the Phylum and Genus Levels

3.3. Association of GM with Clinical Parameters of the Study Participants at the Phylum Level

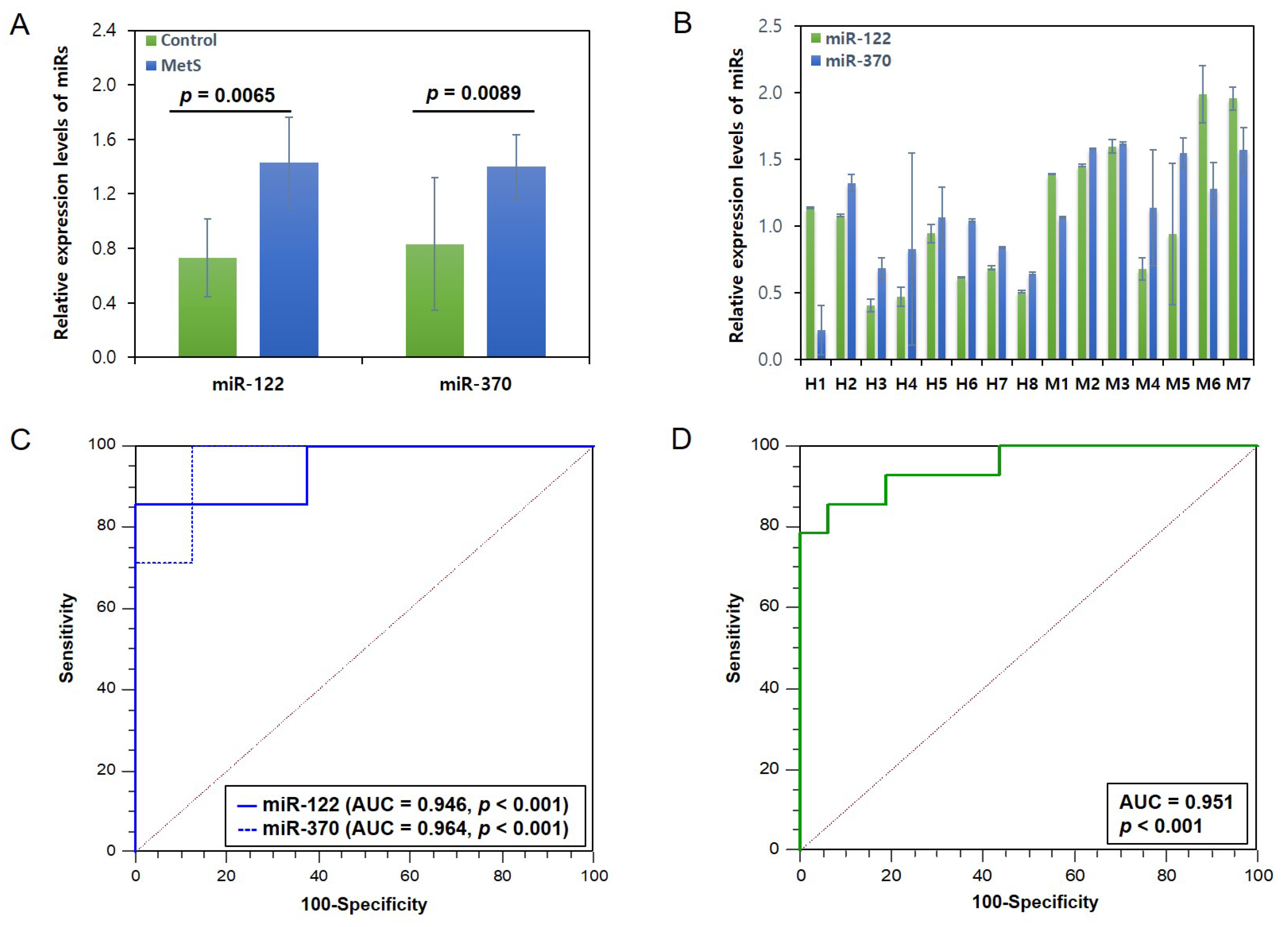

3.4. Expression Levels of the 2 miRs Related to Lipid Metabolism in MetS and Control Groups and Their Potential as MetS Biomarkers

3.5. Correlation Between the Expression Levels of 2 miRs and the GM Abundances in the Individuals with MetS and Controls

3.6. The Power of the Pilot Study

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MetS | Metabolic syndrome |

| miR | MicroRNA |

| GM | Gut microbiota |

| F/B | Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

| ASV | Amplicon sequence variants |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| WC | Waist circumference |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| FBG | Fasting blood glucose |

| Total chol | Total cholesterol |

| HDL chol | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LDL chol | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| TG | Triacylglyceride |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| γ-GTP | γ-glutamyltranspeptidase |

| Serum Cr | Serum creatinine |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| Hs-CRP | High sensitivity-C-reactive protein |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| RT-qPCR | Real-time quantitative PCR |

References

- Hirode, G.; Wong, R.J. Trends in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the United States, 2011–2016. JAMA 2020, 323, 2526–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, P.; Mathangasinghe, Y.; Jayawardena, R.; Hills, A.P.; Misra, A. Prevalence and trends of metabolic syndrome among adults in the Asia-pacific region: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Han, K.; Kang, Y.M.; Kim, S.O.; Cho, Y.K.; Ko, K.S.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, K.U.; Koh, E.H. Trends in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its components in South Korea: Findings from the Korean National Health Insurance Service Database (2009–2013). PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Shin, M.J.; Després, J.P.; Eckel, R.H.; Tuomilehto, J.; Lim, S. 20-year trends in metabolic syndrome among Korean adults from 2001 to 2020. JACC Asia 2023, 3, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundy, S.M.; Brewer, H.B.; Cleeman, J.I.; Smith, S.C.; Lenfant, C. Definition of met-abolic syndrome report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association Conference on Scientific Issues Related to Definition. Circulation 2004, 109, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isomaa, B.; Almgren, P.; Tuomi, T.; Forsén, B.; Lahti, K.; Nissén, M.; Taskinen, M.R.; Groop, L. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syn-drome. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kim, S.A.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Hong, G.; Hong, J.; Choi, K.; Eom, C.S.; Baik, S.Y.; Lee, M.K.; et al. Genetic variants associated with elevated plasma ceramides in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Genes 2022, 13, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Hong, J.; Kim, Y.; Hong, G.; Baik, S.Y.; Choi, K.; Lee, M.K.; Lee, K.R. Identification of genetic variants related to metabolic syndrome by next-generation sequencing. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2022, 14, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsch, I.A.; Konturek, P.C. The role of gut microbiota in obesity and type 2 and type 1 diabetes mellitus: New insights into “old” diseases. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabke, K.; Hendrick, G.; Devkota, S. The gut microbiome and metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 4054057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckey, T.D. Introduction to intestinal microecology. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1972, 25, 1292–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crudele, L.; Gadaleta, R.M.; Cariello, M.; Moschettaa, A. Gut microbiota in the pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches of diabetes. eBioMedicine 2023, 97, 104821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitocco, D.; Leo, M.D.; Tartaglione, L.; Leva, F.D.; Petruzziello, C.; Saviano, A.; Pontecorvi, A.; Ojetti, V. The role of gut microbiota in mediating obesity and diabetes mellitus. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 1548–1562. [Google Scholar]

- Org, E.; Blum, Y.; Kasela, S.; Mehrabian, M.; Kuusisto, J.; Kangas, A.J.; Soininen, P.; Wang, Z.; Ala-Korpela, M.; Hazen, S.L.; et al. Relationships between gut microbiota, plasma metabolites, and metabolic syndrome traits in the METSIM cohort. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wu, W.; Wu, S.; Zheng, H.M.; Li, P.; Sheng, H.F.; Chen, M.X.; Chen, Z.H.; Ji, G.Y.; Zheng, Z.D.X.; et al. Linking gut microbiota, metabolic syndrome and economic status based on a population-level analysis. Microbiome 2018, 6, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozupone, C.A. Getting to know the microbiome. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemente, J.C.; Ursell, L.K.; Parfrey, L.W.; Knight, R. The impact of the gut micro-biota on human health: An integrative view. Cell 2012, 148, 1258–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, M.; Ruiz, A.; Lanza, F.; Haange, S.B.; Oberbach, A.; Till, H.; Bargiela, R.; Campoy, C.; Segura, M.T.; Richter, M.; et al. Microbiota from the distal guts of lean and obese adolescents exhibit partial functional redundancy besides clear differences in community structure. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wutthi-in, M.; Cheevadhanarak, S.; Yasom, S.; Kerdphoo, S.; Thiennimitr, P.; Phrommintikul, A.; Nipon Chattipakorn, C.; Weerayuth Kittichotirat, W.; Chattipakorn, S. Gut microbiota profiles of treated metabolic syndrome patients and their relationship with metabolic syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Shi, B. Gut microbiota as a potential target of metabolic syndrome: The role of probiotics and prebiotics. Cell Biosci. 2017, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.X.; Deng, X.R.; Zhang, C.H.; Yuan, H.J. Gut microbiota and metabolic syndrome. Chin. Med. J. 2020, 133, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Choi, H.N.; Cho, S.R.; Yim, J.E. Association of Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio with body mass index in Korean type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Metabolites 2024, 14, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 2009, 136, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wronska, A. The role of microRNA in the development, diagnosis, and treatment of cardiovascular disease: Recent developments. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2023, 384, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Zhang, J. Circulating microRNAs: Potential and emerging biomarkers for diagnosis of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 730535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderari, S.; Diawara, M.R.; Garaud, A.; Gauguier, D. Biological roles of microRNAs in the control of insulin secretion and action. Physiol. Genom. 2017, 49, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Islam, M.M.; Ripon, M.A.R.; Islam, M.M.; Hossain, M.S. Regulatory roles of microRNAs in the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome. Mol. Biotech. 2024, 66, 1599–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Hernando, C.; Suarez, Y.; Rayner, K.J.; Moore, K.J. MicroRNAs in lipid metabolism. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2011, 22, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulos, D.; Drosatos, K.; Hiyama, Y.; Goldberg, I.J.; Zannis, V.I. MicroRNA-370 controls the expression of microRNA-122 and Cpt1alpha and affects lipid metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 1513–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, F.; D’Souza, R.F.; Durainayagam, B.R.; Milan, A.M.; Markworth, J.F.; Mi-randa-Soberainis, V.; Sequeira, I.R.; Roy, N.C.; Poppiott, S.D.; Mitchell, C.J.; et al. Circulatory miRNA biomarkers of metabolic syndrome. Acta Diabetol. 2020, 57, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, L.; De La Motte, L.R.; Deflorio, L.; Sansisco, D.F.; Salvatici, M.; Micaglio, E.; Biazzo, M.; Giarritiello, F. Systematic review of bidirectional interaction between gut mi-crobiome, miRNAs, and human pathologies. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1540943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalmasso, G.; Nguyen, H.T.; Yan, Y.; Laroui, H.; Charania, M.A.; Ayyadurai, S.; Sitaraman, S.V.; Merlin, D. Microbiota modulate host gene expression via microRNAs. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prukpitikul, P.; Sirivarasai, J.; Sutjarit, N. The molecular chanisms underlying gut microbiota-miRNA interaction in metabolic disorders. Benef. Microbes 2024, 15, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, J.; Wu, K.; Fan, D. Survival prediction of gastric cancer by a seven-microRNA signature. Gut 2010, 9, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Tai, J.W.; Lu, L.F. miRNA-microbiota interaction in gut homeostasis and colorectal Cancer. Trends Cancer 2019, 5, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.T.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Park, H.A.; Shin, J.; Cho, S.H.; Choi, Y.; Shim, J.Y. Clinical practice guideline of prevention and treatment for metabolic syndrome. Korean J. Fam. Pract. 2015, 5, 375–420. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data pro-cessing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introduction to the Microbiome R Package. Available online: https://bioconductor.statistik.tu-dortmund.de/packages/3.6/bioc/vignettes/microbiome/inst/doc/vignette.html (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Gloor, G.B.; Macklaim, J.M.; Pawlowsky-Glahn, V.; Egozcue, J.J. Microbiome datasets are compositional: And this is not optional. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloor, G.B.; Wu, J.R.; Pawlowsky-Glahn, V.; Egozcue, J.J. It’s all relative: Analyzing microbiome data as compositions. Ann. Epidemiol. 2016, 26, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; He, H.W.; Wang, Z.M.; Zhao, H.; Lian, X.Q.; Wang, Y.S.; Zhu, J.; Yan, J.J.; Zhang, D.G.; Yang, Z.J.; et al. Plasma levels of lipometabolism-related miR-122 and miR-370 are increased in patients with hyperlipidemia and associated with coronary artery disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2012, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kang, D.R.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, W.; Jeong, Y.W.; Chun, K.H.; Han, S.H.; Koh, K.K. Metabolic syndrome fact sheet 2024: Executive report. Cardiometab. Syndr. J. 2024, 4, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, K.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Diao, H. MicroRNAs regulate intestinal immunity and gut microbiota for gastrointestinal health: A comprehensive review. Genes 2020, 11, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Weiner, H.L. Control of the gut microbiome by fecal microRNA. Microbial Cell 2016, 3, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, M.; Suga, N.; Fukumoto, A.; Yoshikawa, S.; Matsuda, S. Comprehen-sion of gut microbiota and microRNAs may contribute to the development of innovative treatment tactics against metabolic disorders and psychiatric disorders. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2024, 16, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.E.; El-Masry, S.A.; El Shebini, S.M.; Ahmed, N.H.; Mohamed, T.F.; Mostafa, M.I.; Afify, M.A.; Kamal, A.N.; Badie, M.M.; Hashish, A.; et al. Gut dysbiosis is linked to metabolic syndrome in obese Egyptian women: Potential treatment by probiotics and high fiber diets regimen. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magne, F.; Gotteland, M.; Gauthier, L.; Zazueta, A.; Pesoa, S.; Navarrete, P.; Bal-amurugan, R. The firmicutes/bacteroidetes ratio: Are relevant marker of gut dysbiosis in obese patients? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karačić, A.; Renko, I.; Krznarić, Ž.; Klobučar, S.; Pršo, A.M.L. The association be-tween the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio and body mass among European population with the highest proportion of adults with obesity: An observational follow-up study from Croatia. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, R.E.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Klein, S.; Gordon, J.I. Microbial ecology: Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 2006, 444, 1022–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariat, D.; Firmesse, O.; Levenez, F.; Guimarăes, V.; Sokol, H.; Doré, J.; Corthier, G.; Furet, J.P. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio of the human microbiota changes with age. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohland, C.L.; MacNaughton, W.K. Probiotic bacteria and intestinal epithelial barrier function. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010, 298, G807–G819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Kafaji, G.; Al-Mahroos, G.; Alsayed, N.; Hasan, Z.; Nawaz, S.; Bakhiet, M. Peripheral blood microRNA-15a is a potential biomarker for type 2 diabetes mellitus and pre-diabetes. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 7485–7490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneghan, H.M.; Miller, N.; McAnena, O.J.; O’Brien, T.; Kerin, M.J. Differential miRNA expression in omental adipose tissue and in the circulation of obese patients identifies novel metabolic biomarkers. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, E846–E850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.F.; Wang, L.X.; Zhong, J.M.; Hu, R.Y.; Fang, L.; Wang, H.; Gong, W.W.; Zhang, J.; Pan, J.; Yu, M. Circulating microRNA-21 is downregulated in patients with metabolic syndrome. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2016, 29, 385–389. [Google Scholar]

- Willeit, P.; Skroblin, P.; Moschen, A.R.; Yin, X.; Kaudewitz, D.; Zampetaki, A.; Barwari, T.; Whitehead, M.; Ramírez, C.M.; Goedeke, L.; et al. Circulating microRNA-122 is associated with the risk of new-onset metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2017, 66, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, C.; Lv, M.; Hu, Q.; Guo, L.; Xiong, D. Correlation between alterations of gut microbiota and miR-122-5p expression in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, A.L.; Larsen, L.H.; Udesen, P.B.; Sanz, Y.; Larsen, T.M.; Dalgaard, L.T. Levels of circulating miR-122 are associated with weight loss and metabolic syndrome. Obesity 2020, 28, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Healthy Control | MetS | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 8 | 7 | ||

| Age (years) | 54.3 ± 13.7 | 56.1 ± 14.9 | [−18.0, 15.0] | 0.6431 |

| Height (cm) | 161.9 ± 7.7 | 169.3 ± 10.2 | [−19.0, 4.7] | 0.1824 |

| Weight (kg) | 57.1 ± 2.2 | 80.4 ± 12.1 | [−34.5, −12.4] | 0.0014 |

| WC (cm) | 75.6 ± 1.6 | 96.5 ± 6.9 | [−27.0, −15.0] | 0.0014 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.9 ± 1.6 | 28.0 ± 2.9 | [−9.4, −3.4] | 0.0014 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 111.3 ± 10.2 | 126.0 ± 12.1 | [−28.0, −5.0] | 0.0319 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 67.7 ± 6.7 | 78.7 ± 5.5 | [−19.0, −3.0] | 0.0123 |

| FBG (mg/dL) | 91.2 ± 4.3 | 102.7 ± 5.0 | [−17.0, −5.0] | 0.0029 |

| Total chol (mg/dL) | 199.8 ± 13.2 | 232.9 ± 22.1 | [−53.0, −13.0] | 0.0128 |

| HDL chol (mg/dL) | 69.8 ± 11.1 | 50.4 ± 17.9 | [−2.0, 36.0] | 0.1043 |

| LDL chol (mg/dL) | 114.8 ± 16.3 | 143.0 ± 32.7 | [−63.0, 7.0] | 0.0559 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 96.6 ± 35.1 | 172.4 ± 80.0 | [−161.0, 12.0] | 0.0559 |

| AST (U/L) | 23.1 ± 5.7 | 31.4 ± 7.4 | [−16.0, 0.0] | 0.0479 |

| ALT (U/L) | 22.8 ± 7.1 | 38.7 ± 18.0 | [−26.0, −3.0] | 0.0199 |

| γ-GTP (U/L) | 17.2 ± 4.6 | 43.1 ± 19.8 | [−43.0, −8.0] | 0.0021 |

| Serum Cr (mg/dL) | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | [−0.2, 0.1] | 0.2998 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 88.6 ± 14.9 | 96.6 ± 13.1 | [−28.0, 8.0] | 0.2239 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 2.0 | [−1.7, −0.2] | 0.0014 |

| Insulin (µIU/mL) | 3.2 ± 1.5 | 11.3 ± 3.1 | [−9.5, −5.3] | 0.0014 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | [−2.5, −1.5] | 0.0013 |

| Clinical Parameters | Bacteroidetes | Firmicutes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson | Spearman | Pearson | Spearman | |||||||||

| r a [95% CI] | p | Adjusted p c | rs b [95% CI] | p | Adjusted p c | r a [95% CI] | p | Adjusted p c | rs b [95% CI] | p | Adjusted p c | |

| WC | −0.7186 [−0.8997, −0.3265] | 0.0025 | 0.0425 | −0.6598 [−0.8786, −0.4502] | 0.0074 | 0.1266 | 0.793 [0.4728, 0.9282] | 0.0004 | 0.0068 | 0.6799 [0.4775, 0.9051] | 0.0053 | 0.0900 |

| BMI | −0.6775 [−0.8832, −0.2531] | 0.0055 | 0.0468 | −0.6897 [−0.8822, −0.4660] | 0.0044 | 0.0377 | 0.7765 [0.4389, 0.9220] | 0.0007 | 0.0040 | 0.7107 [0.4968, 0.8980] | 0.003 | 0.0253 |

| SBP | −0.5686 [−0.8371, −0.0795] | 0.0270 | 0.0574 | −0.6152 [−0.8909, −0.0074] | 0.0146 | 0.0829 | 0.4909 [−0.0285, 0.8016] | 0.0632 | 0.1194 | 0.6308 [0.0205, 0.8867] | 0.0117 | 0.0662 |

| DBP | −0.63 [−0.8636, −0.1738] | 0.0118 | 0.0334 | −0.746 [−0.9222, −0.3304] | 0.0014 | 0.0060 | 0.5637 [0.0722, 0.8349] | 0.0286 | 0.0608 | 0.6976 [0.2469, 0.9110] | 0.0038 | 0.0163 |

| FBG | −0.6692 [−0.8798, −0.2388] | 0.0064 | 0.0363 | −0.7178 [−0.9164, −0.4145] | 0.0026 | 0.0088 | 0.7705 [0.4267, 0.9198] | 0.0080 | 0.0227 | 0.6847 [0.3759, 0.8989] | 0.0049 | 0.0165 |

| Total chol | −0.6285 [−0.8629, −0.1714] | 0.0121 | 0.0294 | −0.7751 [−0.9312, −0.5568] | 0.0007 | 0.0019 | 0.7884 [0.4633, 0.9265] | 0.0005 | 0.0043 | 0.6893 [0.3480, 0.8909] | 0.0045 | 0.0127 |

| HDL chol | 0.3309 [−0.2184, 0.7210] | 0.2283 | 0.2985 | 0.2415 [−0.4484, 0.7674] | 0.3859 | 0.9372 | −0.6368 [−0.8664, −0.1848] | 0.0107 | 0.0260 | −0.2323 [−0.7623, 0.4507] | 0.4048 | 0.9831 |

| LDL chol | −0.4331 [−0.7737, 0.1018] | 0.1068 | 0.1816 | −0.5565 [−0.8462, 0.1413] | 0.0312 | 0.0663 | 0.4752 [−0.0490, 0.7941] | 0.0735 | 0.1136 | 0.4942 [−0.1557, 0.8117] | 0.0612 | 0.1299 |

| TG | −0.2376 [−0.6685, 0.3128] | 0.3939 | 0.4185 | −0.4651 [−0.8642, 0.2283] | 0.0807 | 0.1524 | 0.4876 [−0.0328, 0.8000] | 0.0652 | 0.1108 | 0.4458 [−0.2646, 0.8317] | 0.0958 | 0.1809 |

| AST | −0.3067 [−0.7078, 0.2439] | 0.2662 | 0.3232 | −0.3213 [−0.6938, 0.2379] | 0.2429 | 0.4129 | 0.2505 [−0.3003, 0.6760] | 0.3678 | 0.4168 | 0.3426 [−0.2034, 0.6989] | 0.2112 | 0.3590 |

| ALT | −0.2604 [−0.6817, 0.2907] | 0.3487 | 0.3952 | −0.3969 [−0.7503, 0.2210] | 0.1429 | 0.2208 | 0.2374 [−0.3129, 0.6684] | 0.3942 | 0.4188 | 0.4092 [−0.1976, 0.7670] | 0.1299 | 0.2008 |

| γ-GTP | −0.4084 [−0.7614, 0.1314] | 0.1307 | 0.1852 | −0.6962 [−0.9103, −0.4823] | 0.0039 | 0.0056 | 0.4358 [−0.0984, 0.7750] | 0.4358 | 0.4358 | 0.6643 [ 0.4345, 0.8846] | 0.0069 | 0.0098 |

| Serum Cr | −0.0058 [−0.5165, 0.5080] | 0.9836 | 0.9836 | −0.235 [−0.6592, 0.4125] | 0.3992 | 0.5220 | 0.1737 [−0.3716, 0.6299] | 0.1737 | 0.2271 | 0.247 [−0.3849, 0.6539] | 0.3748 | 0.4901 |

| eGFR | −0.4186 [−0.7665, 0.1192] | 0.1204 | 0.1861 | −0.526 [−0.7985, −0.0074] | 0.044 | 0.0534 | 0.3184 [−0.2316, 0.7142] | 0.2474 | 0.3004 | 0.5103 [0.0055, 0.8004] | 0.052 | 0.0631 |

| hs-CRP | −0.4825 [−0.7976, 0.0395] | 0.0685 | 0.1294 | −0.655 [−0.8668, −0.4162] | 0.008 | 0.0091 | 0.4621 [−0.0657, 0.7879] | 0.0829 | 0.1174 | 0.6625 [0.4237, 0.8853] | 0.0071 | 0.0081 |

| Insulin | −0.6433 [−0.8692, −0.1955] | 0.0097 | 0.0330 | −0.6971 [−0.8996, −0.4725] | 0.0039 | 0.0041 | 0.6907 [0.2762, 0.8886] | 0.0044 | 0.0150 | 0.7386 [0.5512, 0.9100] | 0.0017 | 0.0018 |

| HOMA-IR | −0.6635 [−0.8775, −0.2291] | 0.007 | 0.0298 | −0.7168 [−0.9028, −0.4894] | 0.0026 | 0.0026 | 0.733 [0.3535, 0.9053] | 0.0019 | 0.0081 | 0.746 [0.5553, 0.9167] | 0.0014 | 0.0014 |

| miRs | Bacteroidetes | Firmicutes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson | Spearman | Pearson | Spearman | |||||

| r a [95% CI] | p | rs b [95% CI] | p c | r a [95% CI] | p | rs b [95% CI] | p c | |

| miR-122 | −0.6890 [−0.8862, −0.2660] | 0.0048 | −0.6890 [−0.8988, −0.3542] | 0.0045 | 0.6980 [0.2884, 0.8913] | 0.0038 | 0.7160 [0.4007, 0.9235] | 0.0027 |

| miR-370 | −0.8700 [−0.9307, −0.4870] | 0.0003 | −0.8700 [−0.9782, −0.7032] | <0.0001 | 0.7920 [0.4698, 0.9277] | 0.0004 | 0.8820 [0.7308, 0.9845] | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.; Hong, J.; Kim, Y.; Choi, H.-J.; Park, J.; Yun, J.; Kim, Y.-T.; Choi, K.; Baik, S.; Lee, M.-K.; et al. Significant Association Between Abundance of Gut Microbiota and Plasma Levels of microRNAs in Individuals with Metabolic Syndrome and Their Potential as Biomarkers for Metabolic Syndrome: A Pilot Study. Genes 2025, 16, 1161. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101161

Lee S, Hong J, Kim Y, Choi H-J, Park J, Yun J, Kim Y-T, Choi K, Baik S, Lee M-K, et al. Significant Association Between Abundance of Gut Microbiota and Plasma Levels of microRNAs in Individuals with Metabolic Syndrome and Their Potential as Biomarkers for Metabolic Syndrome: A Pilot Study. Genes. 2025; 16(10):1161. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101161

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Sanghoo, Jeonghoon Hong, Yiseul Kim, Hee-Ji Choi, Jinhee Park, Jihye Yun, Yun-Tae Kim, Kyeonghwan Choi, SaeYun Baik, Mi-Kyeong Lee, and et al. 2025. "Significant Association Between Abundance of Gut Microbiota and Plasma Levels of microRNAs in Individuals with Metabolic Syndrome and Their Potential as Biomarkers for Metabolic Syndrome: A Pilot Study" Genes 16, no. 10: 1161. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101161

APA StyleLee, S., Hong, J., Kim, Y., Choi, H.-J., Park, J., Yun, J., Kim, Y.-T., Choi, K., Baik, S., Lee, M.-K., & Lee, K.-R. (2025). Significant Association Between Abundance of Gut Microbiota and Plasma Levels of microRNAs in Individuals with Metabolic Syndrome and Their Potential as Biomarkers for Metabolic Syndrome: A Pilot Study. Genes, 16(10), 1161. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101161